LITERACY NEWS

LAI Newsletter 20_05_2015

LAI Newsletter 20_05_2015

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

August MenuBistro Steak with Walnut Gorgonzola ButterThis steak is a favorite in all Dinner A’Fare kitchens! Our beef shoulder tenderloin is seasoned with kosher salt, and pepper. Slice itand top with walnut and Gorgonzola compound butter, and this bistro steak becomes a must try! (Ziploc Bag)Nutritional Info: Cal 377 /Carbs .8 gm /Protein 31.9 gm /Fat 27.3 gm /Fiber .1 gm /Sodium 308 mg /Chol 73 mgDietary Exchange: 10Jerk Pork Tenderloin with Pineapple ChutneyThis tender and juicy pork tenderloin is crusted with jerk seasoning, a combination of onion, garlic, thyme, allspice, cinnamon,nutmeg, and cayenne pepper. We then add, to create the perfect balance, chutney made from crushed pineapple, vinegar, brown sugar,red onion, jalapeno and cilantro. Your taste buds are going to love this journey to reggae country. (Ziploc Bag)Nutritional Info: Cal 201 /Carbs 17.2 gm /Protein 24.2 gm /Fat 3.9 gm /Fiber .5 gm /Sodium 159 mg /Chol 72 mgDietary Exchange: 4Rustic Chicken and Potato GratinéBoneless, skinless chicken breasts are roasted with red skin potato wedges, brushed with kosher salt, pepper, paprika, garlic and atouch of hot sauce. Topped with plenty of cheddar, Monterey Jack, bacon and green onion then browned to become the perfect rusticFrench gratiné. Serve it with our creamy ranch dipping sauce and your whole family will love it. (Ziploc Bag)Nutritional Info: Cal 369 /Carbs 6.6 gm /Protein 35.9 gm /Fat 22 gm /Fiber 1.3 gm /Sodium 1043 mg /Chol 106 mgDietary Exchange: 9Ranch Dipping Sauce Nutritional Info: Cal 183 /Carbs 1.3 gm /Protein 1.3 gm /Fat 19.3 gm /Fiber 0 gm /Sodium 347 mg /Chol 13 mgDietary Exchange: 5Sesame Tilapia with Braised CabbageThis beautiful, aromatic dish will fill your kitchen with a sweet nuttiness. Our flaky tilapia filets are marinated in sesame oil, Italianseasonings, and chopped garlic, then cooked over a colorful layer of cabbage and carrots braised in white wine. Enlighten your senseswith this dish by candlelight with that special someone. (Ziploc Bag)Nutritional Info: Cal 380 /Carbs 17.7 gm /Protein 26 gm /Fat 23.9 gm /Fiber 3.5 gm /Sodium 358 mg /Chol 56 mgDietary Exchange: 9Maple Mustard Pork ChopsThese center cut pork chops are marinated in Dijon mustard, maple syrup, and orange juice and then sautéed or grilled to perfection.Quick and easy, yet delicious and full of flavor! (Ziploc Bag)Nutritional Info: Cal 220 /Carbs 9.3 gm /Protein 28.5 gm /Fat 7.6 gm /Fiber 0 gm /Sodium 158 mg /Chol 40 mgDietary Exchange: 5Greek Chicken PitasWine, conversation and these fantastic pitas are all you need for a great weekend afternoon! Our boneless, skinless chicken breaststrips are marinated in the customary Greek ingredients of olive oil, lemon juice, garlic, oregano and red onion. Stuff the warm pitas(provided) and top with our traditional tzatziki sauce made from yogurt, cucumber and dill and your afternoon will lead into fun timesand memories. (Ziploc Bag)Nutritional Info: Cal 208 /Carbs 7.2 gm /Protein 28.2 gm /Fat 7.3 gm /Fiber 1 gm /Sodium 291 mg /Chol 70 mgDietary Exchange: 5Pita Bread Nutritional Info: Cal 162 /Carbs 33.4 gm /Protein 5.5 gm /Fat .7 gm /Fiber 1.3 gm /Sodium 322 mg /Chol 0 mgDietary Exchange: 3Honey Bourbon Beef BrisketOur hickory smoked beef brisket has been slow cooked ahead for 16 hours. You add the perfect glaze of honey, bourbon, and barbecuesauce, and your family is going to love the flavor, while you love how easy this is. (Ziploc Bag)Nutritional Info: Cal 279 /Carbs 16.9 gm /Protein 30.5 gm /Fat 9.9 gm /Fiber .5 gm /Sodium 401 mg /Chol 90 mgDietary Exchange: 6

A Message from the PresidentWelcome to the Spring 2015 edition of Reading News.Again this year, the Executive Committee decided topublish the Spring issue in electronic format only, dueto increasing costs associated with typesetting, printingand distribution. Our hope is that the Newsletter inthis format will reach a greater number of readers, andwe urge you to forward this newsletter to your colleagues.LAI had a very busy year in 2013-14, culminating inthe Annual Conference in September at the MarinoInstitute in Dublin, where Elizabeth Moje and GeneMehigan were the keynote speakers. In this issue, mypredecessor as RAI president, Gerry Shiel, provides apersonal reflection on the Conference.Another key event at the conference was the AGMand the decision to change the name from ReadingAssociation of Ireland to Literacy Association of Ireland.As the Executive Committee reflected on thisdecision in the months following the AGM it was decidedto hold an EGM to further discuss this decisionand other potential names for the association. An interestingdiscussion debated various names, howeverdespite not having a quorum, the majority of thosepresent indicated that they would support maintainingthe decision taken at the AGM in September. Thus theassociation was re-launched at a number at an eventin the Mansion House on April 24th (see pages 4-5).Already this year, the Literacy Association of Irelandhas held three events for members – one in Cork, andthe other two in Dublin. A report on the Cork symposium is included on page 11 and two of the presentershave also written articles for this issue of Reading News.In early March, Mollie Cura presented a workshop on the Writers’ Workshop. Details of the workshop areavailable on Mollie’s website: http://www.curaliteracyconsulting.com Towards the end of March, Mark Fennellpresented a seminar at Blackrock Education Centre on Active Learning Pedagogies.This issue of LAI news also includes articles on rhyme, rhythm and repetition in the context of interactingwith stories, and on performance on the most recent national assessment of English reading.Finally, I want to draw your attention to the call for proposals for LAI’s 39th Annual Conference, which takesplace at the Maino Institution of Education on September 22-24th next (see page 6).LAI Ireland greatly appreciates your membership of the Association and the currentCommittee looks forwardto serving you in the months ahead.Fiona Nic FhionnlaoichPresident, 2014-153

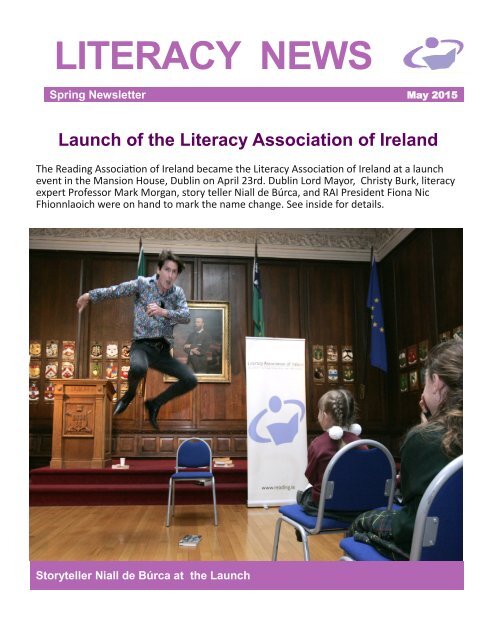

Launch of Literacy Association of IrelandStudents Join Lord Mayor in ‘Read Aloud’ InitiativeTwitter @LiteracyIRL#readaloudApril 23 rd 2015: The Literacy Association of Ireland was launched in Dublin today with an initiative that sawyoung students read aloud from their favourite books, a practice that has been proven to have a positive impacton language and literacy achievement.The Read Aloud initiative saw The Lord Mayor of Dublin, Christy Burke join school children and theirteachers at the Mansion House, each of whom brought their favourite book and read aloud from their preferredpassage.According to the Literacy Association of Ireland (LAI), reading aloud aids comprehension, allows the reader(and the listener) to build a visual image from the words; can assist with language development and is agreat way to recognise and appreciate the pleasure of reading.The aim of the LAI is to help develop literacy in Ireland, across all demographics and age groups, and promoteliteracy as an integrated process involving all four language skills; listening, speaking, reading and writing.Books from which students read aloud included ‘Where the Wild Things Are’ by Maurice Sendak and‘Wonder’ by R.J. Palacio.President of the LAI, Fiona Nic Fhionnlaoich, said, “Our aim is to support and inform all those concerned withthe development of literacy, including teachers, researchers and parents; challenge them in their practice andgive public voice to their concerns around literacy and related-issues.”Formerly known as the Reading Association of Ireland, Fiona Nic Fhionnlaoich explained that the namechange to LAI was made to reflect the more holistic approach that was required to develop literacy in Ireland,an approach that embraces and harnesses the four essential skills involved.“Today is an important milestone for all those concerned with and interested in literacy development. Literacyis a vital skill that goes far beyond reading and writing and it was important that as an organisation, this isreflected in our name and our objectives. Comprehension, interpretation and the ability to communicate effectivelyare more important now than ever before in our face-paced, literate world that uses multiple forms oflanguage and expression.”The event was addressed Dr Mark Morgan, Professor of Education and Psychology at St. Patrick’s CollegeDrumcondra who has conducted numerous studies on literacy. Dr Morgan said; “There is also evidence fromthe 'Growing up in Ireland’ that recreational activities can enhance literacy skills especially where childrenneed to work through structured activities.” He also emphasised the importance of literacy skills in every aspectof children's and adults' lives and especially in relation to social and emotional development. Literacyinfluences are pervasive, he concluded.Widely recognised as one of Ireland’s finest traditional story-tellers, Niall de Búrca supported the launch andenthralled guests at the Mansion House, young and old, with his captivating and animated stories, helping toemphasise the role of story-telling in the development of literacy, at all levels.The Reading Association of Ireland, now the Literacy Association of Ireland, was established in 1975 and isan affiliate of the International Literacy Association.4

Launch of the Literacy Association of IrelandPrimary-levelpupils enjoythe launch ofthe LiteracyAssociation ofIreland at theMansionHouse.Post-primarystudentssharingfavouritebooks at thelaunch.5

Launch of the Literacy Association of IrelandAbove: LAI Executive Committee Members at theLaunch: (from left to right) Gene Mehigan, KateTurley, Caroline Daly, Jennifer O’Sullivan, NiamhFortune, Fiona Nic Fhionnlaoich (LAI President),Edel Stokes, Maírín Wilson, Brendan Culligan andBrian Murphy.Left: Professor Mark Morgan discusses the importanceof literacy.6

LAI 39th International Conference‘Living Literacy: from Tots to Teens’Marino Institute of Education, DublinSeptember 24th-26th 2015CALL FOR PAPERSLAI (formerly RAI) invites proposals for papers and workshops for its 39th annual internationalconference. The theme of this year’s conference is ‘Living Literacy : from Tots toTeens’.The conference will explore research and practice on the following topics:Oral language developmentBest practice in the teaching and study of literacyEmergent literacyPromoting children’s literature in schoolsIntegrated approaches to literacy developmentNew literacies: using digital tools to enhance literacyLiteracy across languagesClassroom-based assessment for literacy (including formative assessment)Research-based best practice for children with literacy difficultiesChallenges and opportunities in today’s changing classroomsFamily and community literacyLearning to teach literacy: teacher educationCuirtear fáilte faoi leith roimh pháipéir nó cheardlanna i nGaeilge. Is féidir téama ón liosta thuas nóábhar eile a bhaineann le múineadh nó measúnú na Gaeilge a roghnú.KEYNOTE SPEAKERCatherine Gilliland, St. Mary’s University College, Belfast.PROPOSAL SUBMISSIONSProposals for papers or workshops (150-300 word abstract) should be submitted by June 12th,2015, using the electronic form at www.reading.ie. Queries by e-mail to LAILiteracy@gmail.com.Please watch our website for ongoing updates and follow us on Twitter @LiteracyIRL7

More than a Name Change: the International ReadingAssociation becomes theInternational Literacy AssociationRAI wasn’t alone in adopting a name change in 2015. On January 26, 2015, the International ReadingAssociation (IRA) officially became the International Literacy Association (ILA). The change from“Reading” to “Literacy” was a crucial step in the organisation’s efforts to emphasise its role as aglobal professional membership association for literacy leaders. The reason for the change wastwofold.Firstly, the change was initiated in response to the concerns of members(the majority of whom are classroom teachers) who indicated thattheir responsibility as educators was to teach a broad spectrum of literaciesincluding writing, oral language, communication skills, digital, visualand critical literacies; and not just reading. Through its network ofmore than 300,000 literacy educators and experts across 75 countries,ILA works to develop, gather and disseminate useful resources, bestpractices and cutting-edge research to empower educators, inspire studentsand inform policy makers. ILA’s research journals (The ReadingTeacher, Reading Research Quarterly and Journal of Adolescent &Adult Literacy) and publications (books, and online resources such as,the E-ssentials and Bridges series) set the standards for how literacy isdefined, taught and evaluated. Visit the website at http://reading.org/general/Publications.aspx for further details. The annual conference ofthe organisation has moved to July. Again this was in response to Bernadette Dwyermembers’ feedback. The conference will be held this year in St. Louis,USA from 18-20 th of July. For further information on the conference, visit the conference website(http://www.reading.org/annual-conference-2015/) where details of speakers and events can befound.Secondly, the name change, building on and solidifying a 60-year legacy, positions the organisationas advocates in advancing literacy in classrooms and communities around the world. There are currently,approximately, 800 million people worldwide who struggle to attain literacy. This is an unacceptableand truly horrifying statistic in the 21 st century. To date the International Literacy Associationhas developed 22 projects to improve literacy levels in the developing world. ILA is wellpositionedto lead the cross-sector collaboration and integration necessary to address illiteracyworldwide. The transformative power of literacy in an individual’s life represents the difference betweeninclusion in, and exclusion from, society. In addition, a literate population creates prosperouseconomies, a just and equal society and more meaningful lives for citizens. Illiteracy is a solvableissue. To tackle illiteracy today, action is needed at all levels- individual, community, national, andinternational levels. With the collective support of members, affiliates (including the Literacy Associationof Ireland) and partners across the globe, the International Literacy Association aims to makethis the Age of Literacy – one where each of us works to transform lives by advancing literacy for all.Bernadette DwyerInternational Literacy Association Board of Directors (2013-2016)8

International Activities: LAI in EuropeThe Literacy Association of Ireland is affiliated to the International Literacy Association (ILA) throughits association with and participation in the International Development in Europe Committee (IDEC)of ILA and enjoys an international profile also through its association with the IDEC partner organisation,the Federation of European Literacy Associations (FELA). LAI nominates one of its ExecutiveCommittee members (currently Dr Brian Murphy, School of Education, UCC) to represent it atthe bi-annual meetings of IDEC and FELA.The European Commission maintains a strong desireto establish a European policy network to raiseawareness, gather and analyse policy information,exchange policy approaches, good practice andpromising campaigns and initiatives to promote literacyin light of the Education and Training framework(ET2020) benchmark that the share of low-achieving 15-years olds in reading across Europeshould be less than 15% by 2020. FELA, through its partner associations, contributed to a successfulbid for the establishment of this European Policy Network of national literacy organisations. Theproject, called ELINET, is now in its second year. For further details, see http://www.eli-net.eu/19th European Conference on LiteracyLiteracy in the New Landscape of Communication: Research, Education andthe EverydayKlagenfurt, Austria, 14–17 July 2015The 19 th European Conference on Reading is scheduled for Klagenfurt, Austria on August 2015. The Conferenceprovides an opportunity to learn about literacy-related activities being implemented in Europe andbeyond. The conference theme reflects new modes of communication and how these may be expected toaffect research, education and everyday practice.Keynote speakers at the conference include:Teresa Cremin, Professor for Literacy at the Faculty of Education and Language Studies Dept. ofEducation (The Open University, UK) will talk about teachers' attitudes towards reading and writing in theclassroom.Jennifer Rowsell, Canada Research Chair in Multiliteracies, Department of Teacher Education(Brock University, Canada), will give us some inputs into "old" and "new" landscapes of literacy.Joseph Winkler, highly nominated Austrian author, recipient of the Georg-Büchner-Preis, the mostprestigious literature award in Germany.Full details at: www.literacyeurope.org or www.felaliteracy.org9

School of Education, UCC & Reading Association of IrelandHost 3rd Annual Literacy Research Symposium for TeachersThe School of EducationUCC and the Reading Associationof Ireland jointlyhosted a very successfulliteracy research symposiumentitled Enhancing theTeaching of Literacy in IrishClassrooms: Insights fromResearch Conducted byTeachers’ on Saturday February7 th 2015. The eventwas very well attended withover 60 teachers participating,coming from primaryand post-primary schoolsfrom West Cork across toFrom left to right, Dr Brian Murphy (Senior Lecturer, School of Education,UCC and Executive Committee RAI; symposium organiser), Máiréad Quinn,Ali Geary, Maria Healy, Fiona Nic Fhionnlaoich (RAI President, 2014-15), ProfessorKathy Hall (Professor of Education and Head of School, UCC) andNiamh Dennehy.West Waterford. This 3rd annual symposium, a key continuing professional development event forteachers in the region, was organised and chaired by Dr Brian Murphy of the School of Education,on behalf of the School of Education, UCC & the Executive Committee of the Reading Associationof Ireland.In the context of an enhanced emphasis on literacy development in all Irish classrooms and a strongdesire for continuous professional development with respect to literacy in schools, the researchsymposium sought to disseminate to teachers at all levels pertinent school and classroom-focusedliteracy research undertaken by teacher researchers who have completed or are in the process ofcompleting MEd degrees at UCC. The symposium provided a forum for the sharing of best practicewith respect to literacy development in key areas ranging from poetry pedagogy to vocabulary, tothe teaching of English and automatic word recognition.Dr Brian Murphy gave the opening address, ‘Current Policy Developments Impinging on LiteracyDevelopment in Schools’, setting the context for the morning. Three MEd students then presentedtheir current research: Ali Geary presented on ‘The Poetry/Pop Music Mash-Up – A Teaching Strategyto Aid Academic Literacy Development in Post-Primary Students’; Maria Healy’s paper was ‘AnExamination of Teachers’ Understandings and Practices of Vocabulary Instruction’ and these werefollowed by Niamh Dennehy, MEd student and Scholarship Holder, on the topical issue of 'An Investigationof the Position of English as a Language in the Post-Primary School Curriculum throughan Examination of Policy and Practice’. The final presentation was by Máiréad Quinn, MEd graduate,on ‘Teaching Word Recognition at Early Primary School: A Study of the Understandings andPractices of Primary Teachers’. The closing session was chaired by Professor Kathy Hall, Head ofthe School of Education, UCC, where she brought together the key themes of the presentations andfacilitated discussion on some of the key issues. The symposium was very well received by all participantsand feedback was extremely positive.12

Metalinguistic Awareness: The Missing Component inthe Teaching of English as a Language in the PostprimarySchool Curriculum?Paper presented by Niamh Dennehy at The School of Education, UCC & Reading Association of Ireland 3rdAnnual Literacy Research Symposium for TeachersIntroductionNiamh DennehyThis article is based on an empirical research study I carried out in an Irish post-primary school inDecember 2013. The research objective of this study was toascertain teachers’ attitudes and practices with regard to theteaching of language, particularly the teaching of metalinguisticawareness. Education research identifies metalinguisticawareness as the specific component of metacognition relatingto language awareness and argues that it is crucial for literacyin all languages, including English, and for general academicachievement at school. Irish policy documents and recentchanges to the Irish post-primary school curriculum, particularlyat junior cycle, also give increased prominence to languageawareness in English as a way of enhancing students’ metacognitive thinking and languagelearning. Arising out of a review of literature on the importance of metalinguistic awareness, I set outto provide additional material on this subject by specifically addressing the divergence between theory,policy and classroom practice. The main research instrument was a focus group interview withteachers of English and foreign languages in an Irish post-primary school.Metalinguistic Awareness: International Research and Irish Policy and CurriculumPerspectivesMetalinguistic awareness is a component of language awareness. It refers to a heightened consciousnessof, and competence in, independent use of the forms and functions of language (Falk,Lindqvist & Bardel, 2013; Rivera-Mills & Plonsky, 2007; Carter, 2003). It is the specific componentof metacognition relating to language awareness and for this reason it is crucial to advanced literacyin the studied language (Hopper, Jayroe & Frans, 2008, p. 7). Metalinguistic awareness enablesstudents to understand language as an abstract concept and evaluate their own knowledge andcompetent use of the language. Knowledge and understanding refers to more than just the ability to“do” something. It also involves the representation of knowledge (Wells, 1999, p. 76). Therefore,students need be conscious of how to manipulate language in order to represent their learning, andin order to develop and use strategies to improve their knowledge and understanding. English is thelanguage of learning at school. Metalinguistic awareness in English enables students to develop“personal responsibility and authority as they develop linguistic confidence, precision and proficiency”(Andrews, 1995, p. 34) therefore it is vitally important for students’ overall academic as well aslanguage development at school. (Cummins, 2001, p. 113).13

Metalinguistic Awareness (continued)Significantly, metalinguistic awareness is particularly important for the “least advantaged, least ablechildren” (Nagy & Anderson, 1995, p. 6) who need explicit instruction in strategies to enable them touse the formal language necessary to access the school curriculum.Metalinguistic awareness in the student’s native language (L1) is also vital for the study of additionallanguages (Cummins, 2001, p. 90; Nagy & Anderson, 1995, p. 6). Students should be able to understand“how the foreign language compares with the pupil’s mother tongue” (Hawkins, 1999, p.140) and use this metalinguistic awareness in their L1 to enable them to become proficient foreignlanguage learners (Nagy & Anderson, 1995, p. 6). This suggests that unless teachers of all languagesuse a shared vocabulary to discuss and teach language (Hawkins, 1999, p. 124), studentsmay be prevented from learning “how” to learn language.At policy and curriculum level in the Irish education system there is an emphasis on the importanceof the explicit teaching of language awareness in all languages, including English, in the classroom(Little, 2003; NCCA, 2005). This language focus is also evident in changes to the new junior cyclecurriculum in English which advocates that students should become “aware of where and how theyare improving in their use of language and conscious of where further improvement is necessary”(DES, 2013, p. 4).Education policy documents also argue that there should be formal assessment of the languageskills and metalinguistic awareness of all languages, including English, in the exam system (Little,2003, p.8; NCCA, 2005, p.1) and that languages in the post primary school curriculum should beintegrated, with common teaching and learning practices applied to all languages (NCCA, 2005; Little,2003).Therefore, the development of metalinguistic awareness is important, not only for proficiency in theL1, but also as a strong basis for the study of second and further languages and for overall academicachievement at school.Research Study Findings and AnalysisAll participants in the focus group phase of this study agreed that English is a more content-focusedthan language-focused subject in post primary school. There is pressure in class to cover content inliterature at the expense of language awareness in the English language due to the volume of contentto be covered in preparation for the state exams. However, the observation was made that studentsmay not always have adequate language skills in English to negotiate the variety and complexityof texts studied.The belief expressed by the English teachers in the group was that focus on the rules of languageor grammar when studying poetry or other texts would possibly interfere with the aesthetic appreciationand enjoyment of the English language and literature. Therefore, unlike practices in the foreignlanguage classroom where instruction in grammar is taught both in context and through direct instruction,in the English classroom teachers many not pay explicit attention to language awarenessduring classroom activities. Participants agreed that students have native proficiency in the Englishlanguage and can therefore use the language quite adequately.14

Metalinguistic Awareness (continued)However, native ability and critical awareness of language as a rules-based system of communicationare not the same thing. The participants commented that students do not always apply therules of grammar in English outside of the strict grammar context which may suggest that studentsdo not have sufficient metalinguistic awareness to know when to actually use rules and conventionsof language in extended pieces of writing.apply the rules of grammar in English outside of the strict grammar context which may suggest thatstudents do not have sufficient metalinguistic awareness to know when to actually use rules andconventions of language in extended pieces of writing.One participant commented that students at ordinary level have very little knowledge of the basicsof English grammar. The difference between language requirements in school and the students’ nativeproficiency suggest that a lack of metalinguistic awareness at this level may impact on students’functional literacy at school. This supports the view that structural awareness of language is mostimportant for students with low levels of literacy (Nagy and Anderson, 1995, p. 6).Participants argued that their primary college degrees in English were focused on literature andtheir initial teacher education was focused on methodology and pedagogy. Therefore, all teachersexpressed a lack of confidence in their own knowledge of the linguistic and structural aspects of theEnglish language. One of the components of the new Junior Cycle English Curriculum (2013) is“Understanding the content and structure of language” (DES, 2013, p. 8). All participants agreedthat extensive linguistic as well as pedagogical training, is required in order to equip teachers to focuson this increased language awareness element in the English classroom.The participants were very aware of the requirements of exam marking schemes in their teachingand all commented that preparation for the exam dominated classroom activity. In their feedback tostudents on homework assignments and assessment work, teachers used exam marking schemecriteria. Therefore, while the teachers corrected and edited students’ language errors, specific attentionwas not drawn to language or grammatical rules that students should study in order to improvethe accuracy of their writing. This is in contrast to foreign language teachers who do actuallyfocus on grammatical rules and structures in their feedback to students. Therefore, students of foreignlanguage know that if they apply particular rules and structures to their use of language theycan improve the standard of their written work. Students do not have this same awareness in theEnglish language.In fact, participants observed that when students begin their study of foreign languages, studentsoften have no reference point from their study of the English language for the grammatical rules andconventions in the foreign language. Students do not even have the terms and vocabulary to namethe parts of grammar that they learn in the foreign language classroom.Therefore, the findings from this focus group suggests that classroom practice and priorities in Englishare different to practices in other language classrooms. This is largely due to a focus on contentin the English classroom. Preparation for the exam dominates activities in the classroom to the exclusionof broader curricular aims. Furthermore, students lack the kind of metalinguistic knowledgein English that they can apply to their study of foreign languages and to improve their proficiencyand accuracy in the English language.15

Conclusions and RecommendationsMetalinguistic Awareness (continued)The findings from this research study suggest that in the absence of a clear language policy, linkedto the National Literacy and Numeracy Strategy (2011) and language curriculum aims, classroompractice with regard to the teaching of language is built around exam requirements. Therefore, aclear and coherent policy on approaches to the teaching of all languages, including English, shouldrun parallel to changes in the curriculum, the literacy policy and the provision of continuous professionaldevelopment for teachers.The development of assessment criteria for the language awareness and metalinguistic element ofthe English language is also necessary. This should form part of an overall assessment policylinked to learning outcomes for the English language in tandem with linguistic and pedagogicaltraining for teachers.Metalinguistic awareness may be the missing component in the teaching of English as a languageto enhance students’ language, literacy and thinking skills as well as their confidence and proficiencyin the English language. I propose that practice-based research on the teaching of English, particularlylanguage and metalinguistic awareness is necessary. Perhaps a pilot-based scheme basedon the teaching English as a rules-based language, called for by the NCCA (2005) would be useful.This would give a practical perspective to add to current research grounded in theory. This maythen lead to the necessary alignment of classroom practices with research, policy and curriculum aswell as investment in teacher education, in order to enhance teaching and learning in the postprimaryschool English classroom in a meaningful way.ReferencesAndrews, L. (1995). Language Awareness: The Whole Elephant. The English Journal, 84(1), pp. 29-34.Carter, R. (2003). Language Awareness. ELT, 57(1), pp. 64 - 65.Cummins, J. (2001). Lingusitic Interdependence and the Educational Development of Bilingual Children. In:Baker, C. and Hornberger, N. (eds) An Introductory Reader to the Writings of Jim Cummins. Clevedon: MultilingualMatters, pp. 222 - 251.Cummins, J. (2001). The Entry and Exit Fallacy. In: Baker, C. and Hornberger, N. (eds) An Introduction to theWriting of Jim Cummins. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters, pp. 110-138.DES. (2011). Literacy and Numeracy for Learning and Life: The National Strategy to Improve Literacy andNumeracy among children and young People 2011-2020. Dublin: Author.DES. (2013). Junior Cycle English Curriculum, Dublin: Author.Falk, Y. Lindqvist. C. & Bardel. C. (2013). The Role of L1 Explicit Metalinguistic Knowledge in L3 Oral Productionat the Initial State. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, available on: CJO 2013 (doi:10.1017), pp.1-9.Hawkins, E. (1999). Foreign Language Study and Language Awareness. Language Awareness, 8(3-4), pp.124 - 142.Hopper, P. Jayroe, T . & Frans, D. (2008). Understanding the Connection between Metacognition, MetalinguisticAwareness and Learning: A Brief Overview for Teachers. Southeastern Teacher Education Journal, 1(1), pp. 7-13.(References continued on page 22)16

An Examination of Teachers’ Understandings andPractices of Vocabulary InstructionPaper presented by Maria Healy at The School of Education, UCC & Reading Association of Ireland 3rd AnnualLiteracy Research Symposium for TeachersVocabulary instruction is significant because our knowledge of words allows us to communicate effectively,understand texts and achieve academically. This study investigates teachers' understandings and teachingsof vocabulary in the primary school. The research project identifies significant features of enriching vocabularyinstruction as highlighted in the research literature. Drawing on interviews with educators as part of asmall study, teachers' beliefs and practices of effective vocabulary teaching is explored. Finally, some importantfindings are discussed, with implications for practitioners to consider for current and future teachings.What makes for effective vocabulary teaching?An abundance of research highlights the need to learn vocabulary in multiple ways across subject areas.Good vocabulary instruction includes the fostering of word consciousness. (Graves, 2006) “Word consciousness”(Scott and Nagy, 2004: 201) is “the knowledge and dispositions necessary for students to learn, appreciateand effectively use words” and is crucial for vocabulary building. Word-conscious students are curiousabout language and like to play with words. (Johnson, 2004:198) This motivates pupils, helps them to reflecton words and ensures active learning. (Blachowicz and Fisher, 2004: 218) Educators can incorporate wordconsciousness into their daily instruction through sharing jokes, riddles, puns, idioms, etc.Which words should we teach?Realistically we cannot teach a viably - sized vocabulary, so we need to focus on which words to address.(Schmitt, 2000: 143) Beck, McKeown and Kucan advocate the use of “Tier Two words” which are “high frequencywords for mature learners”, as they believe there is no way of knowing what “age appropriate vocabulary”is. (2010: 210; 2004: 65) Tier Two words are not the most basic way of expressing an idea, - coincidence,fortunate, perform - but learning these words allows students to describe with greater clarity, peopleand situations with which they already have some familiarity.Tier Two Words (Beck et al. 2010)17

When do we need to teach vocabulary?Vocabulary Instruction (contd.)Effective classrooms provide multiple ways for students to interact with words. (Hiebert and Kamil, 2010: 9) Aword can have flexible meanings so many exposures are needed in different contexts. (Schmitt, 2000: 30)Direct instruction is valuable as isolated, single encounters do not produce enough exposure to learn thenew words being read. (Marzano, 2004: 110) Vocabulary needs to be taught before, during and after readinga text. Similarly, experiences with planned, rich oral language instruction are critical for vocabulary growth.(Nagy, 2010: 28)How should teachers assess vocabulary learning?Despite the need for vocabulary assessment, there does not appear to be an effective method. Cloze testingcan be problematic, as the reader must read and understand other words in a sentence to successfully answer.(Schmitt, 2000: 166) Similarly, tests that only focus on synonyms merely capture “partial knowledge ofthe target word” as the answers will either be marked correct or incorrect and do not show that the studentscan use the word in other contexts. (Schmitt, 2000: 168) Standardised tests are unsuitable as they are nottailored to individual students and therefore do not assess learning of new vocabulary. (Schmitt, 2000: 165)Furthermore, oral assessment can take fifteen minutes per child which is a huge time constraint for teachers.(Biemillar, 2004: 30) Alternatively, Beck et al. (2013) report that different levels of knowledge of a word existsand advocate the use of such a scale to establish how well a student knows a particular word.Levels of Word Knowledge (Beck et al., 2013)Research DesignTo conduct this research, I chose semi-structured interviews to put emphasis on teachers’ understandings and experiences.This small study took place in an urban girls’ primary school. I was provided with the Oral Language Policy,Reading Policy, Literacy Assessment Policy and a compilation of “Vocabulary Building” strategies that were shared bystaff members as part of the School Improvement Plan for Literacy.Research FindingsWhat makes for effective vocabulary teaching?The compilation of “Vocabulary Building” strategies was not mentioned by any teacher during the interviews. Thiswould indicate that the participants may not have access to this document. None of the educators commented on the“Building Bridges of Understanding” programme that is listed as a “current practice and resource in use” for vocabularydevelopment on both the school’s Oral Language18

Vocabulary Instruction (contd.)Policy and Reading Policy. This implies that the programme is not followed by teachers as a vocabularybuilding strategy.The respondents did not say how long they spend teaching vocabulary - “I teach as we’re going along” -which suggests that vocabulary instruction is not timetabled or premeditated by the educators to a great extent.Word consciousness was not a vocabulary strategy mentioned by teachers other than one, who plays an orallanguage game with her class. This may reflect the school’s Literacy Policy as it is not featured on it, which isshocking given the widespread recommendations of word play as an effective instructional approach.Which words should we choose to teach?Similar to Graves, (2006) the participants feel it is important to teach high frequency words and vocabulary from theclass reader. One educator states that she teaches “age appropriate vocabulary” which contradicts Beck et al.’s dispositionthat there is no way of knowing what “age appropriate vocabulary” is. (2010)When do teachers teach vocabulary?All teachers interviewed seem in agreement about providing multiple opportunities to teach new vocabulary. All theeducators appear to make use of reading exercises to expand children’s vocabulary and pre-teach the words beforereading with their class. However, the findings imply that oral language is not used to much extent to teach vocabulary,which is astonishing given the many oral language vocabulary strategies listed on the school policy. This may suggestthat teachers are not fully cognisant of the policy.How do teachers assess vocabulary?Concurrent with the literature on assessment, teachers in the school do not appear to have found an effective methodfor evaluating the new words learnt, in particular due to time constraints. - “This I do find to be a difficulty, because ofthe big number in the classroom”; “it is quite hard to say exactly how much they do know”. This may be because thereare no vocabulary assessment strategies in the Literacy Assessment Policy. The findings indicate that practitioners useoral assessment as their main method of measuring students’ vocabulary learning - “at the end of a term”; or “whenthe time allows”. Interestingly, this reflects the literature which emphasises that oral assessment can take fifteenminutes per student and is therefore not regularly feasible. (Biemillar, 2004) It would seem that the staff need to becomeequipped with specific vocabulary assessment strategies.ImplicationsIn light of the research findings, I propose that the school’s Oral Language Policy be addressed to make it more accessibleto all teachers. The school’s Literacy Policy needs to be revised to include the compilation of “Vocabulary Building”strategies and word consciousness approaches. Teachers’ attention should be drawn to useful resources for teachingvocabulary as part of a balanced literacy programme. A continuing professional development course is needed to upskilleducators on the use of specific vocabulary instruction and assessment strategies, which should then be includedin the Literacy Policy and Assessment Policy. At macro level the Primary School English Curriculum needs to be revisedto guide teachers how to teach and assess vocabulary. A description of explicit strategies to implement vocabulary instructionand assessment with particular reference to word consciousness is necessary.ReferencesBeck, I., McKeown, M. & Kucan, L. (2013) Bringing Words to Life: Robust Vocabulary Instruction 2 nd edn., GuilfordPress, New York.19

ReferencesVocabulary Instruction (contd.)Beck, I., McKeown, M. & Kucan, L. (2013) Bringing Words to Life: Robust Vocabulary Instruction 2 nd edn., GuilfordPress, New York.Beck, I., McKeown, M. & Kucan L. (2010) Choosing words to teach, in Hiebert E. & Kamil M. (eds), Teaching andLearning Vocabulary: Bringing Research to Practice. Routledge, New York, pp. 207-222.Beck I. & McKeown M. (2004) Direct and rich vocabulary instruction, in Baumann J. & Kame’enui E. (eds), VocabularyInstruction: Research to Practice, Guilford Press, New York, pp 13-27.Biemiller A. (2004) Teaching vocabulary in the primary grades: vocabulary instruction needed, in Baumann J. &Kame’enui E. (eds), Vocabulary Instruction: Research to Practice, Guilford Press, New York, pp. 28-40.Blachowicz C. & Fisher J. (2004) Keep the “Fun” in Fundamental: Encouraging word awareness and incidentalword learning in the classroom through word play, in Baumann J. & Kame’enui E. (eds), Vocabulary Instruction:Research to Practice, Guilford Press, New York, pp. 218-238.Blachowicz C. & Fisher J. (2006) Teaching vocabulary in all classrooms, 3rd edn., Pearson Prentice Hall, UpperSaddle River, New Jersey.Bryman A. (2008) Social Research Methods, 3rd edn. Oxford University Press, New York.Graves M. (2006) The Vocabulary Book: Learning & Instruction. Teacher's College Press, New York.Hiebert E. (2010) In pursuit of an effective, efficient vocabulary curriculum for elementary students, in Hiebert E. &Kamil M. (eds), Teaching and Learning Vocabulary: Bringing Research to Practice. Routledge, New York, pp. 243-264.Johnson D., von Hoff Johnson B. & Schlicting K. (2004) Logology: Word and language play, in Baumann J. &Kame’enui E. (eds), Vocabulary Instruction: Research to Practice, Guilford Press, New York, pp. 179-200.Kamil M. & Hiebert E. (2010) Teaching and learning vocabulary: Perspectives and persistent issues, in Hiebert E.& Kamil M. (eds), Teaching and Learning Vocabulary: Bringing Research to Practice. Routledge, New York, pp. 1-26.Marzano R. (2004) The developing vision of vocabulary instruction, in Baumann J. & Kame’enui E. (eds), VocabularyInstruction: Research to Practice, Guilford Press, New York, pp. 100-117.Nagy W. (2010) Why comprehensive instruction needs to be long-term and comprehensive, in Hiebert E. & KamilM. (eds), Teaching and Learning Vocabulary: Bringing Research to Practice. Routledge, New York, pp. 27-44.Neuman S. & Roskos, K (2012) More than teachable moments: Enhancing oral vocabulary instruction in yourclassroom. Reading Teacher 66(1), 63-67.Scott J. &Nagy W. (2004) Developing word consciousness, in Baumann J. & Kame’enui E. (eds), Vocabulary Instruction:Research to Practice. Guilford Press, New York, pp. 201-217.Schmitt N. (2000) Vocabulary in language teaching. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, New York.Stahl, S. and Stahl, K. (2004) Word wizards all! Teaching word meanings in preschool and primary education, inBaumann J. & Kame’enui E. (eds), Vocabulary Instruction: Research to Practice, Guilford Press, New York, pp. 59-79.Stahl S. (2010) Four problems with teaching word meanings (and what to do to make vocabulary an integral partof instruction), in Hiebert E. & Kamil M. (eds), Teaching and Learning Vocabulary: Bringing Research to Practice.Routledge, New York, pp. 95-114.20

Improved Performance on National Assessment ofEnglish ReadingGerry ShielNational assessments of English reading in primary schools have been conducted at regular intervals(every 4-5 years) since 1972. The assessments are implemented in representative samples of150 or so schools and typically involve several thousand pupils. Unlike the standardised tests thatare administered in most schools at the end of each school year, the tests used in the national assessmentsare secure tests that are not available in advance, although sample items are availableonline In both 2009 and 2014, the national assessment of English reading was administered in theSecond and Sixth classes. In both years, testing was conducted in paper-based format only.A key purpose of national assessments is to monitor trends over time. In the past, a significantchange in reading performance has been observed on just one occasion – 10-year olds in 1980achieved a significantly higher mean score than their counterparts in 1972. The purpose of the2009 assessment was to provide baseline data since this wasthe first occasion on which pupils in Second and Sixth had beenassessed. In 2014, there was an opportunity to examine changesin performance since 2009.Much has happened in educational terms between 2009 and2014. In 2010, the results of the 2009 Programme of InternationalStudent Assessment (PISA) were published. The performanceof Irish 15-year olds on print-based reading literacy wasshown to have dropped significantly compared with earlier cyclesand Ireland’s ranking dropped from 5 th to 17 th among countriesin both PISA 2000 and PISA 2009. In 2011, the Departmentof Education and Skills published The National Strategy toImprove Literacy and Numeracy among Children and YoungPeople 2011-2020, in which specific national targets for readingliteracy were set out. The Strategy also included proposals forenhancing teacher education at primary and post-primary levels,and for revising curricula and syllabi in English. In 2012, theoutcomes of the Progress in International Reading LiteracyStudy (PIRLS) were published. Pupils in Fourth in Ireland class ranked 10 th among participatingcountries, with pupils in just five countries, including Northern Ireland, achieving significantly higheraverage scores. In 2013, the outcomes of PISA 2012 were released, and Ireland’s performance onprint-based reading was similar to 2000. Ireland ranked 7 th among 65 countries and had a meanscore that was significantly higher than the average for OECD countries. Meanwhile, following onfrom the National Strategy and subsequent circulars, there has been an increase in the allocation oftime to reading literacy in primary schools, while schools have established targets for literacy andnumeracy in their school improvement plans, and have reported the results of end-of-school-yearstandardised tests to boards of management, parents and to the Department of Education andSkills.21

National Assessment of English Reading (contd.)Pupils in both Second and Sixth classes in the 2014 national assessment showed improved performanceon reading literacy. At Second class, average performance improved from 250 points to 264,while at Sixth class, it improved from 250 to 263. At Second class, 22% of pupils performed at thelowest proficiency levels (Level 1 and below), down from 35% in 2009. At Sixth class, 25% performedat or below Level 1, again down from with 35% in 2009. In 2014, 46% at Second class and44% at Sixth performed at the highest proficiency levels (Levels 3 and 4), up from 35% at both classlevels. Pupils attending DEIS Band 1 schools made significant gains in Second class, while those inBand 2 schools improved at Second and Sixth classes, with a particularly large improvement inBand 2 schools at Second class.Across all school types, girls in 2014 outperformed boys on overall reading in Second class, but notin Sixth. However, girls in Sixth class had a significantly higher mean score on reading comprehensionthan boys in Sixth class ̶ there was no difference on reading vocabulary.The targets established for literacy in the National Strategy (a 5% reduction in the proportion of lowachievers, and a 5% increase in the proportion of high achievers by 2020) were achieved at bothSecond and Sixth class in 2014.While the increases in performance in 2014 are substantive and are to be welcomed, we cannot pinpointwhy performance has improved in a relatively short period of time in a testing programme inwhich it has been difficult to show change in the past. Certainly, it is likely that elements of the NationalStrategy and subsequent circulars, such as the increased allocation of time to the teaching ofliteracy, not just in English classes, but across the curriculum, and increased emphasis on the useof standardised tests in school improvement planning may have made a contribution. The challengegoing forward is to build on the gains achieved in 2014, while ensuring that pupils continue to engagefrequently in leisure reading and are equally comfortable reading paper-based and digitaltexts.A performance report on the 2014 National Assessments of English and Mathematics may be downloadedat http://www.erc.ie/documents/na14report_vol1perf.pdf A context report, which examinesfactors associated with achievement, is currently being prepared.Gerry Shiel, a past-president of RAI and current member of the Executive Committee, works on assessmentat the Educational Research Centre, St Patrick’s College, Drumcondra.__________References from page 16 continued:Little, D. (2003). Languages in the Post Primary Curriculum: a discussion document, Dublin: NCCA.Nagy, W. & Anderson, R. (1995). Metalinguistic Awareness and Literacy Acquisition in Different Languages. Universityof Illinois at Urbana-Champaign: Technical Report no. 618. Available at: https://www.ideals.illinois.edu/bitstream/handle/2142/17594/ctrstreadtechrepv01995i00618opt.pdf, (Accessed: December 14, 2013).NCCA, (2005). Review of Languages in Post-Primary Education: Report on the First Phase of the Review, Dublin: Author.Rivera-Mills, S. & Plonsky, L. (2007). Empowering Students With Language Learning Strategies: A Critical Review ofCurrent Issues. Foreign Language Annals, 40(3), pp. 535-546.Wells, G. (1999). Dialogic Inquiry: Towards a Sociocultural Practice and Theory of Education. New York: CambridgeUniversity Press.22

Rhyme, Rhythm and Repetition make the wheels of the language busgo round and round!!!!Catherine GillilandPH Zurich University held a conference in September 2013 entitled, “Tell me a story show me the world.”The image chosen of children looking over the beauty of our hemisphere and drinking in the many thingsthey can find out about their world is inspiring. It motivated me as a Teacher Educator to further immersemy students in the world of story and to develop their ability to use literary texts to stimulate thinking, engagementand discussion.The five pillars of reading instruction outlined by the (NationalReading Panel, 2000)– phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency,vocabulary and comprehension remind us of the need for balancein our teaching. (Roche,2015,p.6) warns us that, “As thepressure mounts to improve literacy outcomes in Literacy andNumeracy, there is a danger that the notion of Literacy may narrowto decoding and encoding and the teaching of discrete skillsand competencies.”Margaret Clarke reminded us in her Keynote address at the 2013Conference of the importance of High Frequency words. In herarticle in Reading News Summer 2013 she described them as a:A Neglected Resource for Young Literacy learners. She referredto the research of Mc Nally and Murray’s list of the 100 commonestkey words in written texts account for about half of the totalwords in our reading material. (Solidy and Voulsen ,2009 p.509)claim that “the debate may be resolved by teaching the optimal level of core phonological, phonic, andsight vocabulary skills, taught rigorously and systematically in conjunction with real books.”Balance is always something that we as teachers must keep at the forefront of our mind when teaching.Analysis of picture books reveals that they are full of these neglected words and the use of interactivebooks available means that children can be immersed visually in the rereading of their favourite books.When lecturing in this area I use the term “skittery words” to describe them and complete the lecture byreminding the students that if children do not know their “skittery words” they are “skittered”. The dialogicrereading of picture books whilst developing children’s sense of narrative also ensures the developmentof a very robust sight vocabulary.Picture books that are rich in rhyme, rhythm and repetition are the natural food for the reading brain.Responding to rhythm is a natural human reaction since we each carry our own inner metronome.(Bower and Barrett,2014,p118). Julia Donalson’s book the Gruffalo is a prime example of a book thatnaturally pulls children into the reading process. The frequency of rhyme, rhythmn and repetition withinan outstanding storyline is a “real” reading experience for children and ensures the children can enjoythe social, enjoyable activity and simutaneously develop reading like behaviours and essential readingskills. (Goswami, 2007) found that children with very poor rhyming skills have difficulty with rime analogiesand these need to be made explicit in the sharing of picture books. She found that the work of Dr.Seuss was particularly effective in the reading development of dyslexic children. It is the predictability ofof text that is increased by rhythm and rhyme that is vital to learning to read. (Carter,1998). MargaretMeek emphasises the importance of rereading books as she believes that: “the reading of stories makesskilful, powerful readers who come to understand not only the meaning but the forces oftexts.”(1988,p40.) Repeated reading of stories children can begin to develop a more extended vocabulary,which they can utilise in their own own oral and written communications.23

Language Bus (continued)In Gene Meighan’s keynote address at the 2014 conference his excellent analysis of the complexity of thereading process was exemplified by his memory of a child struggling with reading. The child accompanied hisfather on nightly music gigs and had a vast repetoire of language from knowing all the words of the songs onthe play list. It was a reminder to all of us involved in the teaching of reading to fully exploit every opportunityto make language visible for children to see, read and indeed sing along to. Words of songs are also filled tothe brim with”skittery” words.In our classrooms we see children arriving with what (Moat, 2001) describes as word poverty.(Wolf,2010,p.10) further analyses this concept and notes how children from impoverished language environmentshave by the age of five, “heard 32 million fewer words spoken to them than the average middle classchild.” (Bower and Barrett, 2013) recommend that repeated reading of favourite stories is one way to help fillthis word gap.By using short stories to develop vocabulary teachers have thebenefit of developing vocabulary through context. It offers opportunitiesto revisit the words learned and also to understand anduse them in real life communication which guarantees the requiredretention. Nodelman (1988p.284) describes their usefulnessperfectly when he noted, “ the combination of words and picturesis an ideal way to learn a lot in a relatively painless way.”The same could also be said of the family of finger, action andnursery rhymes. We must constantly remember not to knock MissMuffet off her tuffet, keeping our hands up for finger rhymes andensuring that action rhymes make the wheels of the language busgo round and round! The indepth work of (Bruce and Spratt,2011)provides a sound argument for daily involvement with rhyme. There are numerous literacy benefits of repeatedreadings and clapping of rhymes, games and associated actions. As (Bower and Barrett,2013 p. 130)acknowledge that “most children and adults find it easier to learn and remember songs and rhymes thanstraight prose because of the regular rhythm and predictable rhyme.”In conclusion the importance of training and retraining our teachers to appreciate the value in daily immersionwith rhyme, rhythm and repetition as best case Literacy provision is paramount. Making this teaching asvisual as possible will ensure the five pillars of reading instruction are being met simultaneously within a realbook environment. If we ate a 500 ml pot of full fat delicious ice cream everyday we would expect considerableweight gain at the end of the month. A diet of high quality picture books rich in rhyme, rhythm and repetitionand engagement with the rhyme family will develop the reading brain.ReferencesBruce, T and Spratt, J. (2011) Essentials of Literacy from 0 -7 (2 nd edn). London: SageBower, V and Barrett, S. (2014) ‘Rhythm, rhyme and repetition’, in Bower, V, Developing Early Literacy 0 – 8 from theoryto practice. London, Sage.Carter, D. (1998) Teaching Poetry in the Primary School. London: David Fulton.Clarke, M. M. (2013) High Frequency Words: A neglected Resource for Young Literacy Learners, Reading News, Summer2013.Goswami, U. (2007) ‘ Analogical reasoning in children’ , in J.Campione, K. Metz and A. S Palincsar (eds), Children’slearning in laboaratory and classroom context. Abingdon:Routledge.24

Language Bus (continued)Meek, M. (1998) How Texts Teach What Children Learn. Stroud: Thimble PressMoats, L. (2001) ‘Overcoming the Language gap’, American Educator,25 (5): 8-9National Reading Panel (NRP) (2000). Teaching children to read; An evidence – based assessment of thescientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. Washington,DE: NationalReading PanelNodelman, P. (1998) Words about Pictures: the narrative art of children’s picture books. Athens, GA: Universityof Georgia PressRoche, M. (2015). Developing Children’s Critical Thinking through Picturebooks. Oxon: RoutledgeSolity,J. and Voulston, J. (2009) Real books veresus reading schemes:a new perspective from instructionalpsychology. Eduational psychology, 29 (4), 469-511.Wolf, M. (2010) Proust and the Squid: The story and the science of the reading brain. Cambridge: IconBooks.Catherine Gilliland is a Senior Lecturer in Language and Literacy in St Mary’sUniversity College in Belfast. She is very committed to inspiring Undergraduateand Post Graduate students to be creative and informed practitioners in theirteaching of Literacy. She uses puppets and story telling as a medium for ignitingcreativity. She has presented at both the 2013 and 2014 RAI Conferences. Sheis well known for her workshop on Paddy the Polar Bear for developing vocabularyand comprehension. It is aimed at 8 -12 years children and has been presentedin Zurich, Madrid, Bristol, Holland and Dublin.LAI WebsiteTo keep up-to-date on the latest LAI news, visit www.reading.ie. The website provides informationabout upcoming events, in addition to national and international developments in reading and literacy.Links to useful websites to support teachers are provided, with a focus on English, Gaeilge andEnglish as an additional language. The most recent information about the conference in Septemberwill be available from the website and anyone who wishes to present can find the details and theapplication form on the website.Members can also access articles published as part of the proceedings of previous conferencesand some of the presentations are also available. In the next number of weeks, members will alsobe given access to podcasts of interviews with keynote speakers from previous conferences andadditional practical ideas for the classroom. Members who have forgotten or mislaid their membershiplog-in can send an email to info@reading.ie requesting a new (reset) password.25

Biennial Award for anOutstanding Thesis on LiteracyThe Literacy Association of Ireland invites Graduate Students from Education, Special Education,Psychology and related disciplines to apply for LAI’s 6 th biennial award for an outstanding Master’sthesis.Award: LAI Medal & €500This award is open to those who have submitted OR who plan to submit a Master’s thesis in the areaof literacy between:2 nd September 2013 and 1 st September 2015Applicants must submit, by 15 h July, 2015:1) A 3,000 word summary of the thesis in hardcopy and a PDF attachment via email. (Do notinclude any identifying details on this file: e.g. your name/supervisor/institution).2) A separate note from the Supervisor of the thesis supporting the submissionShortlisting will take place (according to criteria below) and finalists will make a short presentation(15-20 mins) of their research at the Literacy Association of Ireland Annual Conference to be heldon 24 th Sept – 26 th Sept 2015 at the Marino College of Education, Griffith Avenue, Dublin 9.Shortlisted applicants are ineligible to present additional papers on their thesis research at the conference.3) A single sheet separate from the summary with the thesis title, author’s name and contact details.Send to: Eithne Kennedy, Literacy Asociation of Ireland, Outstanding Thesis on Literacy, c/o EducationDept., St. Patrick’s College, Drumcondra, Dublin 9. email: eithne.kennedy@.dcu.ieThesis summaries will be evaluated by an independent panel convened by the Literacy Associationof Ireland according to criteria which will include: (a) relevance and significance of the researchquestion (s); (b) Quality of theoretical/conceptual rationale; (c) Appropriateness of research design;(d) Significance of the research findings/contribution to the field; (e) Clarity of writing and organisationof summary (f) Breadth of references. In addition, the communicative clarity of the presentationat the conference will be considered. Shortlisted finalists will be notified by September 14th. If two ormore theses are deemed by the judges to be of equal quality, the award may be shared. The winner(s) will be presented with the award (s) at the end of the LAI conference. Applicants must be currentmembers of LAI.26

The Popcorn Initiative: The Use of Kindles to MotivateBoys to Readby Denise Mitchell, Jill Dunn and Terry Leatham, Stranmillis University College, BelfastResearch (Purvis, 2011; Shirlow, 2012; Nolan, 2014) indicates an educational underperformance ofboys from working class protestant areas in Northern Ireland. The 2011 GCSE figures, indicate thatonly 19.7% of protestant boys, from these areas are achieving 5 GCSE grades A* - C (DENI 2012).The underperformance starts in the early years of schooling and is most evident in literacy with resultsshowing that only 14.78% of boys meet Level Three reading targets compared with 22.58 % ofgirls (CCEA , 2013).In order to enhance literacy learning there has been a recent growth in use of e-readers with Rainie(2012) indicating that there are four times more people reading e-books on a typical day now thanwas the case less than two years ago. Good and Sinek (2013) agree that the percentage of childrenwho have read an ebook has almost doubled since 2010 (25% vs. 46%). They report that half ofchildren age 9-17 say they would read more books for fun if they had greater access toebooks..Doiron (2011) states that educators need to understand the motivational influence of thesedigital tools and to accept them as positive and useful in promoting positive reading habits. Educators,according to Barack (2011), are now exploring how Kindles and other e-readers can mesh withcurricula and enhance learning and they believe that the educational payoff could be huge.A primary school in a protestant area of inner city Belfast decided to pilot an initiative using Kindlesto motivate Year 7 boys to read a novel. The initiative ran from the end of April to mid-June in thesummer term of 2014. The initial book chosen for the Kindle was ‘Danny Champion of the World’ asit was thought this story would appeal to boys. The boys were asked to read the Kindles each nightand also for 20 mins each day during silent reading time after lunch. The boys were required to reada target percentage per week and every Friday there was a discussion based on the chapters readthat week. When the book was finished the movie based on the book was viewed in school. Thenovel and film were then compared and contrasted through a written exercise. On completion eachboy received 2 cinema tickets.The methodology chosen included questionnaires to 18 boys in Year 7 before the Initiative started.These were followed by interviews with 2 focus groups of boys (12 boys) from each Year 7 class inApril 2014 and at the end of the pilot in June 2014. Interviews were also conducted in June 2014with both Year 7 teachers and with the school Principal.The research project set out to examine the boys’ attitudes to reading and findings indicate that theboys all recognized the importance of reading for their education and future employment and themajority of those surveyed and interviewed claimed that they like reading. The boys were alsoknowledgeable about authors and books they would like to read. However, for many of the boysreading is not perceived as a priority activity.27

Another aim of the research was to ascertain if Kindles would motivate boys to engage in morereading. Overall the boys were interested, excited and motivated in becoming involved in the projectand they treated the Kindles with care. However, in relation to the question of whether Kindleswill encourage boys to read more books. Some of boys thought they would as: ‘Boys like gadgetsso maybe a gadget for the sake of it,’ also ‘Boys like electronics….so will encourage more peoplethan books.’ There were other boys who were not convinced that Kindles would and as one boystated: ‘We have better things to do than read, play football…Xbox ,run around the streets.’ Anotheracknowledged that: ‘No, you are still reading, no difference.’ It may be the case that reading on aKindle may not encourage those boys who do not read fiction voluntarily to engage in future reading.The Principal and Year 7 teachers all agreed that the Kindles ‘Really motivated the boys…reallypositive about it.’. One Year 7 teacher also found that: ‘The boys were very excited about the prospectof reading from a Kindle.’ Another stated that ‘Sometimes you have to say ‘get your books out’but with the Kindles I didn’t have to say once….even during break time which is unheard of.’The principal recognized that ‘The cinema tickets have kept their attention.’ One of the Year 7teachers agreed that the cinema tickets ‘had a huge impact on them….a good incentive….somethingwe could use again.’ Some of the boys when asked how boys could be encouragedto read using Kindles agreed with the Principal that if the movie tickets had not been offeredthey would not have engaged in the process. One boy stated ‘unless more than 2 cinema tickets,don’t take the offer.’ Another suggested ‘four cinema tickets,.’ Other prizes were suggested such as‘a free holiday’ or ‘a pencil at the end.’ So it could be argued that A kindle alone may not be enoughof an incentive for boys to read: additional ‘prizes’ may be necessary.In conclusion it would appear that the Kindle initiative got Year 7 boys reading a novel which few ofthem would have done during this time period. The Principal believed that this is a positive thingand there may be ‘The subliminal message ‘I have read a book….it is something I could do again.’He hopes that maybe we have made a difference’. The school plans to use Kindles with all Year 7pupils throughout the forthcoming academic year.28

Language, Literacy and Literature: Re-imaginingTeaching and LearningNiamh Fortune, Aoibheann Kelly and Fiona Nic Fhionnlaoich (Editors)This volume comprises a selection of papers on a range of topicspresented at the 37th Annual Reading Association of IrelandConference in September, 2013. The theme of the conferencecoincides with the title of the volume, Language, Literacyand Literature: Re-imagining Teaching and Learning.In the first chapter Brian Murphy investigates the beliefs,knowledge and experiences of post-primary student teachersabout reading literacy. According to Literacy and Numeracyfor Learning and Life: The National Strategy to ImproveLiteracy among Children and Young People, all teachers, includingpost-primary subject teachers, will be expected to supportthe literacy development of their students. Surveyed studentteachers generally revealed restricted understandings ofliteracy, and narrow conceptions regarding the responsibilityfor and the pedagogy of literacy development. Results are discussedin terms of the pressing need to deepen and extendstudent teachers’ understanding, knowledge and pedagogyof literacy development in initial teacher education.In Chapter 2, Ciara Ní Bhroin draws on picture book research and reader response theory to examinethe interaction of text and image in a range of classic and contemporary picture books that allowchildren to explore concepts such as narrative perspective, dual or multiple narratives, the unreliablenarrator, subplots, irony and intertextuality. Implications for teachers and teacher educators regardingchoosing and evaluating literature for children are considered.Tara Concannon-Gibney’ discusses in Chapter 3 how to teach early literacy skills using a big book.These reading skills include the ‘five pillars’ of reading instruction outlined by the US National ReadingPanel (NRP)- phonemic, awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary and comprehension and alsoother important aspects of reading development such as developing concepts about print. This paperhighlights how the big book can be used as a meaningful context encouraging children to seethe usefulness of learning these skills as well as engaging them in the lesson.The research by Anne Guerin in Chapter 4 examines the implications of a seven-week programmeof repeated readings on the fluency levels of three struggling adolescent students. This paper exploreshow a broad consideration of the variables involved in reading impacts on the fluency ofstruggling adolescent readers. In addition to improved levels of fluency, the findings indicate thatsuccess lies in the potential of such instructional programmes to enable students to uncovermeaning in text by becoming more strategic as readers through increased levels of self-directed29

Language, Literacy and Literature: Re-imaginingLearning (contd.)Teaching andlearning, and demonstrates the necessity for practitioners to observe caution in the assessment andinstruction of reading.Chapter 5, ‘Challenges and Opportunities in Today’s Changing Classrooms: Planning to Supportthe Development of Literacy Skills in the Early Years’ by Bairbre Tiernan and Paula Kerins, focuseson supporting literacy development for all pupils, including those with learning difficulties and/or specialeducational needs in their early years at school. Early literacy skills that are needed to supportliteracy development are highlighted. The paper addresses the practical issues central to planningfor literacy development in mainstream classes, so as to meet individual learning needs and facilitategreater access the curriculum for all.Chapter 6, by Brendan Mc Mahon, is the second to examine literacy development at second level inIreland. Traditionally, consideration of literacy in Irish secondary schools has been overshadowedby attention to literacy at primary level and has been predominantly located within deficit discourseswhich emphasise students’ difficulties and needs. This chapter draws on data from a researchstudy on disciplinary literacy undertaken in secondary schools in 2010 and focuses specifically onthe attitudes and practices of subject teachers with regard to supporting literacy in the classroom.Findings are examined in relation to actions outlined in Literacy and Numeracy for Life and in thecontext of proposals at wider policy level.In Chapter 7, James Johnson discusses the differences between teaching writing and using writingto learn. The introductory part dicusses major reasons for the use of writing in the content subjectsincluding History, Science, Mathematics, and the arts subjects. Different techniques are examinedto integrate the use of writing as a learning tool into the various subjects: quick writes, journaling,admit and exit slips, poetic forms, public writing, performance poetry, Readers’ Theater, commercialsand posters.In 2008, the National Behaviour Support Service introduced the Teacher as Researcher Project, anaction research literacy and learning initiative. Teachers in partner schools have piloted a vastrange of literacy interventions, programmes and resources, gathering and analysing data throughout.Chapter 8, by Jean Henefer and Fiona Richardson, presents an overview of the NBSS Teacheras Researcher Project, highlighting the range and creativity of the work conducted by the teachersas well as findings from their research.Chapter 9, by Joan Kiely, provides an evaluation of a research-based parental story-reading projecttargeted at 3-5 year old children in an area of socio-economic disadvantage. The paper focuses onthe literature review for the research project, establishing what the research suggests is the bestmodus operandi for home-based parental story-reading. Implications for the running of a parentalstory-reading project are presented.In Chapter 10, Julia Kara-Soteriou discusses how teachers can best use their school’s computer labto introduce activities that were inconceivable without the use of technology and to help studentsdevelop new literacies skills. This paper will especially appeal to classroom teachers and technologycoordinators who are interested in developing their students’ new literacies skills.30

Language, Literacy and Literature: Re-imaginingLearning (contd.)Teaching andChapter 11, by Eithne Kennedy and Gerry Shiel, examines the assessment of writing as part ofthe Write To Read research initiative. This intervention which is being implemented in socioeconomicallydisadvantaged primary schools in Dublin (Ireland), at all class levels, includes a writing workshopas one of its key components. The workshop includes self-selection of topics for writing, theuse of mini-lessons to teach key writing strategies, and extensive feedback during teacher-pupilconferencesChapter 12, by Norma McElligott, presents research on the impact of sixth class children workingcollaboratively with their peers to enhance their persuasive communication and writing skills. Themotivation for this study arose when the researcher noted that the pupils in her classroom encountereda number of difficulties with writing persuasive texts such as organising ideas, expressingviewpoints and structuring the layout. This encouraged the researcher to explore relevant researchand to design an intervention that promoted pupils working collaboratively with their peers to enhancetheir persuasive communication and writing skills. Norma was recipient of the 2013 RAI OutstandingMasters’ Thesis in Literacy Award.The final chapter, by Tríona Stokes, examines the potential for English and Drama to work as equalpartners through subject integration. With the development of oral language as the key outcome ofthe work, the paper examines how the English Primary School Curriculum (1999) can promote specifically,Receptiveness to language and Emotional and imaginative development through language.The 2010 Pixar animation movie, Up, is used as a stimulus for the exploration of the theme of ageism.Although print copies of the Proceedings are no longer available, a pdf version can be accessed onthe Literacy Association of Ireland website at http://www.reading.ie/publicationsHowth Midsummer Literary Arts Festival 2015Howth Co. Dublin — June 5-7Includes an extensive programme of activities around children’s literaturefor both children and adults.Featured speakers include Niall de Búrca and Anne MarkeyFull details athttp://www.howthliteraryfestival.com/31