Motherhood in Childhood

EN-SWOP2013

EN-SWOP2013

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

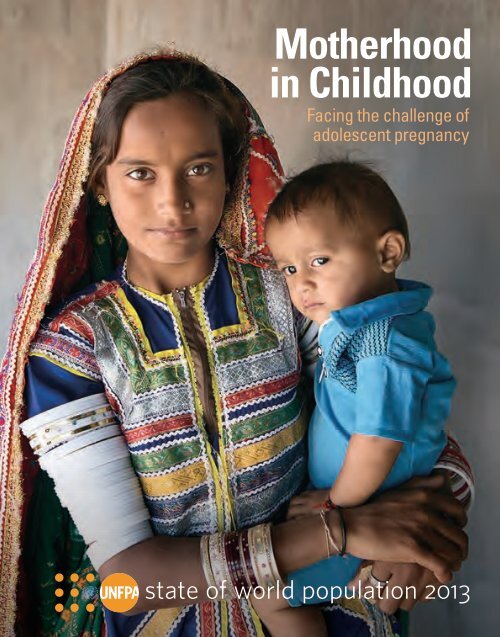

<strong>Motherhood</strong><strong>in</strong> <strong>Childhood</strong>Fac<strong>in</strong>g the challenge ofadolescent pregnancystate of world population 2013

The State of World Population 2013This report was produced by the Informationand External Relations Division of UNFPA, theUnited Nations Population Fund.LEAD RESEARCHER AND AUTHORNancy Williamson, PhD, teaches at the Gill<strong>in</strong>gs School ofGlobal Public Health, University of North Carol<strong>in</strong>a. Earlier,she served as Director of USAID’s YouthNet Project and theBotswana Basha Lesedi youth project funded by the U.S.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. She taught atBrown University, worked for the Population Council and forFamily Health International. She lived <strong>in</strong> and worked on familyplann<strong>in</strong>g projects <strong>in</strong> India and the Philipp<strong>in</strong>es. Author ofnumerous scholarly papers, Ms. Williamson is also the authorof Sons or daughters: a cross-cultural survey of parental preferences,about preferences for sons or daughters around the world.RESEARCH ADVISERRobert W. Blum, MD, MPH, PhD, is the William H. Gates,Sr. Professor and Chair of the Department of Population,Family and Reproductive Health and Director of the Hopk<strong>in</strong>sUrban Health Institute at the Johns Hopk<strong>in</strong>s BloombergSchool of Public Health. Dr Blum is <strong>in</strong>ternationally recognizedfor his expertise and advocacy related to adolescentsexual and reproductive health research. He has edited twobooks and written more than 250 articles, book chaptersand reports. He is the former president of the Society forAdolescent Medic<strong>in</strong>e, past board chair of the GuttmacherInstitute, a member of the United States National Academy ofSciences and a consultant to the World Health Organizationand UNFPA.UNFPA ADVISORY TEAMBruce CampbellKate GilmoreMona KaidbeyLaura LaskiEdilberto LoaizaSonia Mart<strong>in</strong>elli-HeckadonNiyi OjuolapeJagdish UpadhyaySylvia WongEDITORIAL TEAMEditor: Richard KollodgeEditorial associate: Robert PuchalikEditorial and adm<strong>in</strong>istrative associate: Mirey ChaljubDistribution manager: Jayesh GulrajaniDesign: Prographics, Inc.Cover photo: © Mark Tuschman/Planned Parenthood GlobalACKNOWLEDGMENTSThe editorial team is grateful for additional <strong>in</strong>sights, contributionsand feedback from UNFPA colleagues, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g AlfonsoBarragues, Abubakar Dungus, Nicole Foster, Luis Mora andDianne Stewart. Edilberto Loiaza produced the statistical analysisthat provided the foundation for this report.Our thanks also go to UNFPA colleagues Aicha El Basri,Jens-Hagen Eschenbaecher, Nicole Foster, Adebayo Fayoy<strong>in</strong>,Hugues Kone, William A. Ryan, Alvaro Serrano and numerouscollegues from UNFPA offices around the world for develop<strong>in</strong>gfeature stories and for mak<strong>in</strong>g sure that adolescents’ own voiceswere reflected <strong>in</strong> the report.A number of recommendations <strong>in</strong> the report are based onresearch by Kwabena Osei-Danquah and Rachel Snow atUNFPA on progress achieved s<strong>in</strong>ce the Programme of Actionwas adopted at the 1994 International Conference on Populationand Development.Shireen Jejeebhoy of the Population Council reviewed literatureand provided text on sexual violence aga<strong>in</strong>st adolescents. NicolaJones of the Overseas Development Institute summarizedresearch on cash transfers. Monica Kothari of Macro Internationalanalysed Demographic and Health Survey data on adolescentreproductive health. Christ<strong>in</strong>a Zampas led the research anddraft<strong>in</strong>g of aspects of the report that address the human rightsdimension of adolescent pregnancy.MAPS AND DESIGNATIONSThe designations employed and the presentation of material <strong>in</strong>maps <strong>in</strong> this report do not imply the expression of any op<strong>in</strong>ionwhatsoever on the part of UNFPA concern<strong>in</strong>g the legal statusof any country, territory, city or area or its authorities, or concern<strong>in</strong>gthe delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. A dottedl<strong>in</strong>e approximately represents the L<strong>in</strong>e of Control <strong>in</strong> Jammu andKashmir agreed upon by India and Pakistan. The f<strong>in</strong>al status ofJammu and Kashmir has not yet been agreed upon by the parties.UNFPADeliver<strong>in</strong>g a world whereevery pregnancy is wantedevery childbirth is safe andevery young person’spotential is fulfilled

state of world population 2013<strong>Motherhood</strong><strong>in</strong> <strong>Childhood</strong>Fac<strong>in</strong>g the challenge ofadolescent pregnancyForewordpage iiOverviewpage iv1A global challengepage 123Pressures4The impact on girls' health,education and productivityfrom many directionsTak<strong>in</strong>g actionpage 17page 31page 57Chart<strong>in</strong>g a way forwardpage 835Indicators page 99Bibliography page 111© Getty Images/Camilla Watson

ForewordWhen a girl becomes pregnant, her present and future change radically,and rarely for the better. Her education may end, her job prospects evaporate,and her vulnerabilities to poverty, exclusion and dependency multiply.Many countries have taken up the cause ofprevent<strong>in</strong>g adolescent pregnancies, often throughactions aimed at chang<strong>in</strong>g a girl’s behaviour.Implicit <strong>in</strong> such <strong>in</strong>terventions are a belief thatthe girl is responsible for prevent<strong>in</strong>g pregnancyand an assumption that if she does becomepregnant, she is at fault.Such approaches and th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>g are misguidedbecause they fail to account for the circumstancesand societal pressures that conspire aga<strong>in</strong>stadolescent girls and make motherhood a likelyoutcome of their transition from childhood toadulthood. When a young girl is forced <strong>in</strong>to marriage,for example, she rarely has a say <strong>in</strong> whether,when or how often she will become pregnant. Apregnancy-prevention <strong>in</strong>tervention, whether anadvertis<strong>in</strong>g campaign or a condom distributionprogramme, is irrelevant to a girl who has nopower to make any consequential decisions.What is needed is a new way of th<strong>in</strong>k<strong>in</strong>gabout the challenge of adolescent pregnancy.Instead of view<strong>in</strong>g the girl as the problem andchang<strong>in</strong>g her behaviour as the solution, governments,communities, families and schoolsshould see poverty, gender <strong>in</strong>equality, discrim<strong>in</strong>ation,lack of access to services, and negativeviews about girls and women as the realchallenges, and the pursuit of social justice,equitable development and the empowermentof girls as the true pathway to fewer adolescentpregnancies.Efforts—and resources—to prevent adolescentpregnancy have typically focused on girlsages 15 to 19. Yet, the girls with the greatestvulnerabilities, and who face the greatest risk ofcomplications and death from pregnancy andchildbirth, are 14 or younger. This group of veryyoung adolescents is typically overlooked by, orbeyond the reach of, national health, educationand development <strong>in</strong>stitutions, often because thesegirls are <strong>in</strong> forced marriages and are preventedfrom attend<strong>in</strong>g school or access<strong>in</strong>g sexual andreproductive health services. Their needs areimmense, and governments, civil society, communitiesand the <strong>in</strong>ternational community must domuch more to protect them and support their safeand healthy transition from childhood and adolescenceto adulthood. In address<strong>in</strong>g adolescentpregnancy, the real measure of success—or failure—ofgovernments, development agencies, civilsociety and communities is how well or poorly werespond to the needs of this neglected group.Adolescent pregnancy is <strong>in</strong>tertw<strong>in</strong>ed with issuesof human rights. A pregnant girl who is pressuredor forced to leave school, for example, is deniedher right to an education. A girl who is forbiddenfrom access<strong>in</strong>g contraception or even <strong>in</strong>formationabout prevent<strong>in</strong>g a pregnancy is denied her rightii ii FOREWORD

to health. Conversely, a girl who is able to enjoyher right to education and stays <strong>in</strong> school is lesslikely to become pregnant than her counterpartwho drops out or is forced out. The enjoymentof one right thus puts her <strong>in</strong> a better position toenjoy others.From a human rights perspective, a girlwho becomes pregnant—regardless of thecircumstances or reasons—is one whose rightsare underm<strong>in</strong>ed.Investments <strong>in</strong> human capital are critical toprotect<strong>in</strong>g these rights. Such <strong>in</strong>vestments notonly help girls realize their full potential, but theyare also part of a government’s responsibility forprotect<strong>in</strong>g the rights of girls and comply<strong>in</strong>g withhuman rights treaties and <strong>in</strong>struments, such as theConvention on the Rights of the Child, and with<strong>in</strong>ternational agreements, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g the Programmeof Action of the 1994 International Conference onPopulation and Development, which cont<strong>in</strong>ues toguide the work of UNFPA today.The <strong>in</strong>ternational community is develop<strong>in</strong>ga new susta<strong>in</strong>able development agenda tosucceed the Millennium Declaration and itsassociated Millennium Development Goals after2015. Governments committed to reduc<strong>in</strong>g thenumber of adolescent pregnancies should alsobe committed to ensur<strong>in</strong>g that the needs, challenges,aspirations, vulnerabilities and rights ofadolescents, especially girls, are fully considered<strong>in</strong> this new development agenda.There are 580 million adolescent girls <strong>in</strong> theworld. Four out of five of them live <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>gcountries. Invest<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> them today will unleashtheir full potential to shape humanity’s future.Dr Babatunde Osotimeh<strong>in</strong>United Nations Under-Secretary-Generaland Executive DirectorUNFPA, the United Nations Population Funds Dr Osotimeh<strong>in</strong>with adolescentpeer educators<strong>in</strong> South Africa.© UNFPA/RayanaRassoolTHE STATE OF WORLD POPULATION 2013iii

OverviewEvery day, 20,000 girls below age 18 give birth <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g countries.Births to girls also occur <strong>in</strong> developed countries but on a much smaller scale.In every region of the world, impoverished,poorly educated and rural girls are more likelyto become pregnant than their wealthier, urban,educated counterparts. Girls who are from anethnic m<strong>in</strong>ority or marg<strong>in</strong>alized group, who lackchoices and opportunities <strong>in</strong> life, or who havelimited or no access to sexual and reproductivehealth, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g contraceptive <strong>in</strong>formation andservices, are also more likely to become pregnant.Most of the world’s births to adolescents—95 per cent—occur <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g countries, andn<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> 10 of these births occur with<strong>in</strong> marriageor a union.About 19 per cent of young women <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>gcountries become pregnant before age18. Girls under 15 account for 2 millionof the 7.3 million births that occur toadolescent girls under 18 every year <strong>in</strong>develop<strong>in</strong>g countries.Impact on health, education andproductivityA pregnancy can have immediate and last<strong>in</strong>gconsequences for a girl’s health, education and<strong>in</strong>come-earn<strong>in</strong>g potential. And it often alters thecourse of her entire life. How it alters her lifedepends <strong>in</strong> part on how old—or young—she is.The risk of maternal death for mothers under 15<strong>in</strong> low- and middle-<strong>in</strong>come countries is double thatof older females; and this younger group facesFACING THE CHALLENGE OF ADOLESCENT PREGNANCY• 20,000 girls giv<strong>in</strong>g birth every day• Missed educational and other opportunities• 70,000 adolescent deaths annually fromcomplications from pregnancy, childbirth• 3.2 million unsafe abortions amongadolescents each year• Perpetuation of poverty and exclusion• Basic human rights denied• Girls' potential go<strong>in</strong>g unfulfillediv©Naresh Newar/ipsnews.net

“I was 14… My mom and her sisters began toprepare food, and my dad asked my brothers,sisters and me to wear our best clothesbecause we were about to have a party.Because I didn’t know what was go<strong>in</strong>g on, Icelebrated like everyone else. It was that daysignificantly higher rates of obstetric fistulaethan their older peers as well.About 70,000 adolescents <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>gcountries die annually of causes related topregnancy and childbirth. Pregnancy andchildbirth are a lead<strong>in</strong>g cause of deathfor older adolescent females <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>gcountries. Adolescents who becomepregnant tend to be from lower-<strong>in</strong>comehouseholds and be nutritionally depleted.Health problems are more likely if a girlbecomes pregnant too soon after reach<strong>in</strong>gpuberty.Girls who rema<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> school longer areless likely to become pregnant. EducationI learned that it was my wedd<strong>in</strong>g and that Ihad to jo<strong>in</strong> my husband. I tried to escape butwas caught. So I found myself with a husbandthree times older than me…. This marriage wassupposed to save me from debauchery. Schoolwas over, just like that. Ten months later, Ifound myself with a baby <strong>in</strong> my arms. One dayI decided to run away, but I agreed to comeback to my husband if he would let me goback to school. I returned to school, havethree children and am <strong>in</strong> seventh grade.”Clarisse, 17, ChadUNDERLYING CAUSES• Child marriage• Gender <strong>in</strong>equalityPREGNANCY BEFORE AGE 18• Obstacles to human rights• Poverty• Sexual violence and coercion• National policies restrict<strong>in</strong>g access tocontraception, age-appropriate sexuality education• Lack of access to education and reproductivehealth services• Under<strong>in</strong>vestment <strong>in</strong> adolescent girls’ human capital19%About 19 per centof young women <strong>in</strong>develop<strong>in</strong>g countriesbecome pregnantbefore age 18v

prepares girls for jobs and livelihoods, raises theirself-esteem and their status <strong>in</strong> their householdsand communities, and gives them more say <strong>in</strong>decisions that affect their lives. Education alsoreduces the likelihood of child marriage anddelays childbear<strong>in</strong>g, lead<strong>in</strong>g eventually to healthierbirth outcomes. Leav<strong>in</strong>g school—because ofpregnancy or any other reason—can jeopardize agirl’s future economic prospects and exclude herfrom other opportunities <strong>in</strong> life.Many forces conspir<strong>in</strong>g aga<strong>in</strong>stadolescent girlsAn “ecological” approach to adolescent pregnancyis one that takes <strong>in</strong>to account the full range ofcomplex drivers of adolescent pregnancy and the<strong>in</strong>terplay of these forces. It can help governments,policymakers and stakeholders understand thechallenges and craft more effective <strong>in</strong>terventionsthat will not only reduce the number of pregnanciesbut that will also help tear down the manybarriers to girls’ empowerment so that pregnancyis no longer the likely outcome.One such ecological model, developed byRobert Blum at the Johns Hopk<strong>in</strong>s BloombergSchool of Public Health, sheds light on theconstellation of forces that conspire aga<strong>in</strong>st theadolescent girl and <strong>in</strong>crease the likelihood thatshe will become pregnant. While these forces arenumerous and multi-layered, they all, <strong>in</strong> one wayor another, <strong>in</strong>terfere with a girl’s ability to enjoyor exercise rights and empower her to shape herown future. The model accounts for forces atthe national level—such as policies regard<strong>in</strong>gadolescents’ access to contraception or lack ofenforcement of laws bann<strong>in</strong>g child marriage—all the way to the level of the <strong>in</strong>dividual, suchas a girl’s socialization and the way it shapesher beliefs about pregnancy.Most of the determ<strong>in</strong>ants <strong>in</strong> this modeloperate at more than one level. For example,national-level policies may restrict adolescents’PRESSURES FROM MANY DIRECTIONS AND LEVELSAn “ecological” approach to adolescent pregnancy is one that takes <strong>in</strong>to account the fullrange of complex drivers of adolescent pregnancy and the <strong>in</strong>terplay of these forces.Pressures from all levels conspire aga<strong>in</strong>st girls and lead to pregnancies, <strong>in</strong>tended or otherwise. National laws may prevent agirl from access<strong>in</strong>g contraception. Community norms and attitudes may block her access to sexual and reproductive healthservices or condone violence aga<strong>in</strong>st her if she manages to access services anyway. Family members may force her <strong>in</strong>tomarriage where she has little or no power to say “no” to hav<strong>in</strong>g children. Schools may not offer sexuality education, so shemust rely on <strong>in</strong>formation (often <strong>in</strong>accurate) from peers about sexuality, pregnancy and contraception. Her partner may refuseto use a condom or may forbid her from us<strong>in</strong>g contraception of any sort.viINDIVIDUALFAMILYSCHOOL/PEERSCOMMUNITY

access to sexual and reproductive health services,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g contraception, while the community orfamily may oppose girls’ access<strong>in</strong>g comprehensivesexuality education or other <strong>in</strong>formation abouthow to prevent a pregnancy.This model shows that adolescent pregnanciesdo not occur <strong>in</strong> a vacuum but are the consequenceof an <strong>in</strong>terlock<strong>in</strong>g set of factors such aswidespread poverty, communities’ and families’acceptance of child marriage, and <strong>in</strong>adequateefforts to keep girls <strong>in</strong> school.For most adolescents below age 18, and especiallyfor those younger than 15, pregnanciesare not the result of a deliberate choice. To thecontrary, pregnancies are generally the resultof an absence of choices and of circumstancesbeyond a girl’s control. Early pregnancies reflectpowerlessness, poverty and pressures—frompartners, peers, families and communities. And<strong>in</strong> too many <strong>in</strong>stances, they are the result ofsexual violence or coercion. Girls who havelittle autonomy—particularly those <strong>in</strong> forcedmarriages—have little say about whether orwhen they become pregnant.Adolescent pregnancy is both a cause andconsequence of rights violations. Pregnancyunderm<strong>in</strong>es a girl’s possibilities for exercis<strong>in</strong>gthe rights to education, health and autonomy,as guaranteed <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>ternational treaties such asthe Convention on the Rights of the Child.Conversely, when a girl is unable to enjoy basicrights, such as the right to education, she becomesmore vulnerable to becom<strong>in</strong>g pregnant. Accord<strong>in</strong>gto the Convention on the Rights of the Child,anyone under the age of 18 is considered achild. For nearly 200 adolescent girls every day,early pregnancy results <strong>in</strong> the ultimate rightsviolation—death.Girls’ rights are already protected—on paper—by an <strong>in</strong>ternational, normative framework thatrequires governments to take steps that will makeit possible for girls to enjoy their rights to anADOLESCENT BIRTHS95%95 per cent of theworld’s births toadolescents occur<strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>gcountriesNATIONALvii

education, to health and to live free fromviolence and coercion. Children have the samehuman rights as adults, but they are also grantedspecial protections to address the <strong>in</strong>equities thatcome with their age.Uphold<strong>in</strong>g the rights that girls are entitled tocan help elim<strong>in</strong>ate many of the conditions thatcontribute to adolescent pregnancy and helpmitigate many of the consequences to the girl,her household and her community.Address<strong>in</strong>g these challenges through measuresthat protect human rights is key to end<strong>in</strong>g avicious cycle of rights <strong>in</strong>fr<strong>in</strong>gements, poverty,<strong>in</strong>equality, exclusion and adolescent pregnancy.A human rights approach to adolescentpregnancy means work<strong>in</strong>g with governmentsto remove obstacles to girls’ enjoyment of rights.This means address<strong>in</strong>g underly<strong>in</strong>g causes, suchas child marriage, sexual violence and coercion,lack of access to education and sexual andreproductive health, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g contraception and<strong>in</strong>formation. Governments, however, cannot dothis alone. Other stakeholders and duty-bearers,such as teachers, parents, and community leaders,also play an important role.Address<strong>in</strong>g underly<strong>in</strong>g causesBecause adolescent pregnancy is the result ofdiverse underly<strong>in</strong>g societal, economic and otherforces, prevent<strong>in</strong>g it requires multidimensionalstrategies that are oriented towards girls’ empowermentand tailored to particular populations ofgirls, especially those who are marg<strong>in</strong>alized andmost vulnerable.Many of the actions by governments and civilsociety that have reduced adolescent fertilitywere designed to achieve other objectives, suchas keep<strong>in</strong>g girls <strong>in</strong> school, prevent<strong>in</strong>g HIV <strong>in</strong>fection,or end<strong>in</strong>g child marriage. These actions canalso build human capital, impart <strong>in</strong>formation orskills to empower girls to make decisions <strong>in</strong> lifeand uphold or protect girls’ basic human rights.FOUNDATIONS FOR PROGRESSEMPOWER GIRLSBuild<strong>in</strong>g girls' agency, enabl<strong>in</strong>gthem to make decisions <strong>in</strong> lifeRECTIFY GENDERINEQUALITYPut girls and boys on equal foot<strong>in</strong>gRESPECT HUMANRIGHTS FOR ALLUphold<strong>in</strong>g rights can elim<strong>in</strong>ateconditions that contribute toadolescent pregnancyREDUCE POVERTYIn develop<strong>in</strong>g and developedcountries, poverty drives adolescentpregnancyviii

Research shows that address<strong>in</strong>g un<strong>in</strong>tendedpregnancy among adolescents requires holisticapproaches, and because the challenges aregreat and complex, no s<strong>in</strong>gle sector or organizationcan face them on its own. Only bywork<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> partnership, across sectors, and <strong>in</strong>collaboration with adolescents themselves, canconstra<strong>in</strong>ts on their progress be removed.Keep<strong>in</strong>g adolescent girls on healthy, safeand affirm<strong>in</strong>g life trajectories requires comprehensive,strategic, and targeted <strong>in</strong>vestmentsthat address the multiple sources of theirvulnerabilities, which vary by age, abilities,<strong>in</strong>come group, place of residence and manyother factors. It also requires deliberate effortsto recognize the diverse circumstances ofadolescents and identify girls at greatest riskof adolescent pregnancy and poor reproductivehealth outcomes. Such multi-sectoralprogrammes are needed to build girls’ assetsacross the board—<strong>in</strong> health, education andlivelihoods—but also to empower girls throughsocial support networks and <strong>in</strong>crease their statusat home, <strong>in</strong> the family, <strong>in</strong> the community and <strong>in</strong>relationships. Less complex but strategic <strong>in</strong>terventionsmay also make a difference. These could<strong>in</strong>clude the provision of conditional cash transfersto girls to enable them to rema<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> school.The way forwardMany countries have taken action aimed at prevent<strong>in</strong>gadolescent pregnancy, and <strong>in</strong> some cases,to support girls who have become pregnant. Butmany of the measures to date have been primarilyabout chang<strong>in</strong>g the behaviour of the girl, fail<strong>in</strong>gto address underly<strong>in</strong>g determ<strong>in</strong>ants and drivers,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g gender <strong>in</strong>equality, poverty, sexualviolence and coercion, child marriage, socialpressures, exclusion from educational and jobopportunities and negative attitudes and stereotypesabout adolescent girls, as well as neglect<strong>in</strong>gto take <strong>in</strong>to account the role of boys and men.EIGHT WAYS TO GET THERE1 Girls 10 to 14Preventive <strong>in</strong>terventions for young adolescents2 Child marriageStop marriage under 18, prevent sexual violence and coercion5 EducationGet girls <strong>in</strong> school and enable them to stay enrolled longer6 Engage men and boysHelp them be part of the solution3 Multilevel approachesBuild girls' assets across the board; keep girls on healthy,safe life trajectories4 Human rightsProtect rights to health, education, security and freedomfrom poverty7 Sexuality education and access to servicesExpand age-appropriate <strong>in</strong>formation, provide healthservices used by adolescents8 Equitable developmentBuild a post-MDG framework based on human rights,equality, susta<strong>in</strong>abilityix

“The reality is that people are veryjudgmental, and that’s how human be<strong>in</strong>gsare. To hear that even after all youraccomplishments… all the stuff you’vegone through to pass these hurdles, tobecome a better person… people can bevery unforgiv<strong>in</strong>g because they are go<strong>in</strong>gto remember ‘Oh, she had a baby whenshe was 15’.”Tonette, 31, pregnant at 15, JamaicaExperience from effective programmes suggeststhat what is needed is a transformativeshift away from narrowly focused <strong>in</strong>terventionstargeted at girls or at prevent<strong>in</strong>g pregnancy,towards broad-based approaches that build girls’human capital, focus on their agency to makedecisions about their lives (<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g mattersof sexual and reproductive health), and presentreal opportunities for girls so that motherhoodis not seen as their only dest<strong>in</strong>y. This new paradigmmust target the circumstances, conditions,norms, values and structural forces that perpetuateadolescent pregnancies on the one handand that isolate and marg<strong>in</strong>alize pregnant girlson the other. Girls need both access to sexualand reproductive health services and <strong>in</strong>formationand to be unburdened from the economicand social pressures that too often translate <strong>in</strong>toa pregnancy and the poverty, poor health andunrealized human potential that come with it.THE BENEFITSHEALTHEDUCATIONALEQUALITYBETTERMATERNAL ANDCHILD HEALTHMORE GIRLSCOMPLETINGTHEIR EDUCATIONEQUALRIGHTS ANDOPPORTUNITYLater pregnancies reducehealth risks to girls and totheir children.This reduces the likelihood of childmarriage and delays childbear<strong>in</strong>g,lead<strong>in</strong>g eventually to healthier birthoutcomes. Also builds skills, raisesgirls' status.Prevent<strong>in</strong>g pregnancy helpsensure girls enjoy all basichuman rights.x

Additional efforts must be made to reachgirls under age 15, whose needs and vulnerabilitiesare especially great. Efforts to preventpregnancies among girls older than 15 or tosupport older adolescents who are pregnantor who have given birth may be unsuitable orirrelevant to very young adolescents. Very youngadolescents have special vulnerabilities, and toolittle has been done to understand and respondto the daunt<strong>in</strong>g challenges they face.Girls who have become pregnant needsupport, not stigma. Governments, <strong>in</strong>ternationalorganizations, civil society, communities,families, religious leaders and adolescentsthemselves all have an important role <strong>in</strong>effect<strong>in</strong>g change. All will ga<strong>in</strong> by nurtur<strong>in</strong>gthe vast possibilities that these young girls,brimm<strong>in</strong>g with life and hope, represent.UNFPA, RIGHTS AND ADOLESCENT PREGNANCYFor UNFPA, which is guided by the Programme of Action of theInternational Conference on Population and Development (ICPD),respect<strong>in</strong>g, protect<strong>in</strong>g and fulfill<strong>in</strong>g adolescents’ human rights, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>gtheir right to sexual and reproductive health and their reproductive rights:• Reduces vulnerabilities, especially among those who are the mostmarg<strong>in</strong>alized, by focus<strong>in</strong>g on their particular needs;• Increases and strengthens the participation of civil society, thecommunity and adolescents themselves;• Empowers adolescents to cont<strong>in</strong>ue their education and lead productiveand satisfy<strong>in</strong>g lives;• Increases transparency and accountability; and• Leads to susta<strong>in</strong>ed social change as human rights-based programmeshave an impact on norms and values, structures, policy and practice.ECONOMICPOTENTIALINCREASED ECONOMICPRODUCTIVITY ANDEMPLOYMENTInvestments that empowergirls improve <strong>in</strong>come-earn<strong>in</strong>gprospects.ADOLESCENTGIRLS' POTENTIALFULLY REALIZEDProspects are brighter for agirl who is healthy, educatedand able to enjoy rights.©Mark Tuschman

xiiCHAPTER 1: A GLOBAL CHALLENGE

1A globalchallengeEvery year <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g countries,7.3 million girls under the age of 18give birth.© Mark Tuschman/AMMDTHE STATE OF WORLD POPULATION 20131

“I was 16 and never missed a day of school. I liked study<strong>in</strong>g so much, I would much ratherspend time with my books than watch TV! I dreamt of go<strong>in</strong>g to college and then gett<strong>in</strong>g agood job so that I could take my parents away from the d<strong>in</strong>gy house we lived <strong>in</strong>.Then one day, I was told that I had to leave it all, as my parents bartered me for a girl my elderbrother was to marry. Such exchange marriages are called atta-satta <strong>in</strong> my community. I was sadand angry. I pleaded with my mother, but my father had made up his m<strong>in</strong>d.My only hope was that my husband would let me complete my studies. But he got mepregnant even before I turned 17. S<strong>in</strong>ce then, I have hardly ever been allowed to step out of thehouse. Everyone goes out shopp<strong>in</strong>g and for movies and neighbourhood functions, but not me.Sometimes, when the others are not at home, I read my old school books, and hold my babyand cry. She is such an adorable little girl, but I am blamed for not hav<strong>in</strong>g a son.But th<strong>in</strong>gs are gradually chang<strong>in</strong>g. Hopefully, customs like atta-satta and child marriage will betotally gone by the time my daughter grows up, and she will get to complete her education andmarry only when she wants to.”Komal, 18, IndiaEvery year <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g countries, 7.3 milliongirls under the age of 18 give birth (UNFPA,2013). The number of pregnancies is even higher.Adolescent pregnancies occur with vary<strong>in</strong>gfrequency across regions and countries, with<strong>in</strong>countries and across age and <strong>in</strong>come groups.What is common to every region, however, isthat girls who are poor, live <strong>in</strong> rural or remoteareas and who are illiterate or have little educationare more likely to become pregnant thantheir wealthier, urban, educated counterparts.Girls who are from an ethnic m<strong>in</strong>ority ormarg<strong>in</strong>alized group, who lack choices andopportunities <strong>in</strong> life, or who have limited orno access to sexual and reproductive health,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g contraceptive <strong>in</strong>formation and services,are also more likely to become pregnant.Worldwide, a girl is more likely tobecome pregnant under circumstances ofsocial exclusion, poverty, marg<strong>in</strong>alizationand gender <strong>in</strong>equality, where she is unableto fully enjoy or exercise her basic human2 CHAPTER 1: A GLOBAL CHALLENGE

ights, or where access to health care, school<strong>in</strong>g,<strong>in</strong>formation, services and economic opportunitiesis limited.Most births to adolescents—95 per cent—occur <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g countries, and n<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> 10of these births occur with<strong>in</strong> marriage or a union(World Health Organization, 2008).Accord<strong>in</strong>g to estimates for 2010,36.4 million women <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>gcountries between ages 20 and 24report hav<strong>in</strong>g had a birth before age 18.Births to girls under age 18About 19 per cent of young women <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>gcountries become pregnant before age 18(UNFPA, 2013).Accord<strong>in</strong>g to estimates for 2010, 36.4 millionwomen <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g countries between ages 20and 24 report hav<strong>in</strong>g had a birth before age 18.Of that total, 17.4 million are <strong>in</strong> South Asia.Among develop<strong>in</strong>g regions, West and CentralAfrica have the largest percentage (28 per cent)of women between the ages of 20 and 24 whoreported a birth before age 18.Data gathered <strong>in</strong> 54 countries through twosets of demographic and health surveys (DHS)and multiple <strong>in</strong>dicator cluster surveys (MICS)carried out between 1990 and 2008 andbetween 1997 and 2011 show a slight decl<strong>in</strong>e<strong>in</strong> the percentage of women between the ages of20 and 24 who reported a birth before age 18:from about 23 per cent to about 20 per cent.tAbriendoOportunidadesoffers safe spaces,mentor<strong>in</strong>g, educationalopportunitiesand solidarity foradolescent Mayangirls. It also <strong>in</strong>troducesnew possibilities <strong>in</strong>totheir lives.© Mark Tuschman/UNFPATHE STATE OF WORLD POPULATION 20133

The 54 countries covered by these surveys arehome to 72 per cent of the total population ofdevelop<strong>in</strong>g countries, exclud<strong>in</strong>g Ch<strong>in</strong>a.Of the 15 countries with a “high” prevalence(30 per cent or greater) of adolescentpregnancy, eight have seen a reduction, whencompar<strong>in</strong>g f<strong>in</strong>d<strong>in</strong>gs from DHS and MICSsurveys (1997–2008 and 2001–2011). Thesix countries that saw <strong>in</strong>creases were all <strong>in</strong>sub-Saharan Africa.Under the Convention on the Rights of theChild, anyone under age 18 is considered a“child.” Girls who become pregnant before 18are often unable to enjoy or exercise their rights,such as their right to an education, to healthand an adequate standard of liv<strong>in</strong>g, and thus aredenied these basic rights. Millions of girls under18 become pregnant <strong>in</strong> marriage or <strong>in</strong> a union.The Human Rights Committee has jo<strong>in</strong>ed otherrights-monitor<strong>in</strong>g bodies <strong>in</strong> recommend<strong>in</strong>g legalreform to elim<strong>in</strong>ate child marriage.Births to girls under age 15Girls under age 15 account for 2 million of the7.3 million births to girls under 18 every year<strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g countries.COUNTRIES WITH 20 PER CENT OR MORE OF WOMENAGES 20 TO 24 REPORTING A BIRTH BEFORE AGE 18Per cent5545352515505144 46 484233 34 35 35 36 38 38 38 4020 20 21 21 21 22 22 22 22 22 23 24 24 25 25 25 25 25 26 26 28 28 28 28 29 30ColombiaSource: www.dev<strong>in</strong>fo.org/mdg5b4 CHAPTER 1: A GLOBAL CHALLENGEBoliviaZimbabweMauritaniaEcuadorSenegalIndiaCape VerdeSwazilandEthiopiaBen<strong>in</strong>El SalvadorGuatemalaYemenDom<strong>in</strong>ican RepublicSão Tomé and Pr<strong>in</strong>cipeDemocratic Republic of CongoEritreaKenyaHondurasNigeriaNicaraguaBurk<strong>in</strong>a FasoTanzaniaRepublic of the CongoCameroonUgandaZambiaMalawiGabonMadagascarCentral African RepublicLiberiaSierra LeoneBangladeshMozambiqueGu<strong>in</strong>eaMaliChadNiger

Accord<strong>in</strong>g to DHS and MICS surveys,3 per cent of young women <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>gcountries say they gave birth before age 15(UNFPA, 2013).Among develop<strong>in</strong>g regions, West andCentral Africa account for the largestpercentage (6 per cent) of reported birthsbefore age 15, while Eastern Europe andCentral Asia account for the smallestpercentage (0.2 per cent).Data gathered <strong>in</strong> 54 countries through twosets of DHS and MICS surveys carried outbetween 1990 and 2008 and between 1997and 2011 show a decl<strong>in</strong>e <strong>in</strong> the percentage ofwomen between the ages of 20 and 24 whoreported a birth before age 15, from 4 per centto 3 per cent. The decl<strong>in</strong>e, which has beenrapid <strong>in</strong> some countries, is attributed largelyto a decrease <strong>in</strong> very early arranged marriages(World Health Organization, 2011b).Still, one girl <strong>in</strong> 10 has a child before the ageof 15 <strong>in</strong> Bangladesh, Chad, Gu<strong>in</strong>ea, Mali,Mozambique and Niger, countries wherechild marriage is common.Lat<strong>in</strong> America and the Caribbean is the onlyregion where births to girls under age 15 rose.In this region, such births are projected to riseslightly through 2030.In sub-Saharan Africa, births to girls underage 15 are projected to nearly double <strong>in</strong> thenext 17 years. By 2030, the number of mothersunder age 15 <strong>in</strong> sub-Saharan Africa isexpected to equal those <strong>in</strong> South Asia.First-hand and qualitative data on this groupof very young adolescents—between the agesof 10 and 14—are scarce, <strong>in</strong>complete or nonexistentfor many countries, render<strong>in</strong>g thesegirls and the challenges they face <strong>in</strong>visible topolicymakers.“I was go<strong>in</strong>g out with my boyfriend for ayear and he used to give me money andclothes. I got pregnant when I was 13.I was still <strong>in</strong> school. My parents askedmy boyfriend to stay at our place. Hepromised them that he would take care ofme. After that, he left. He stopped call<strong>in</strong>gand I had no contact with him. After Idelivered my baby my parents took careof me and taught me how to take care ofhim. All I want is…to go back to school.After school I will be able to have aprofession like be<strong>in</strong>g a teacher andhave a driver’s license.”Ilda, 15, MozambiqueThe ma<strong>in</strong> reason for the paucity of reliable,complete data is that 15-year-olds are typicallythe youngest adolescents <strong>in</strong>cluded <strong>in</strong> nationalDHS surveys, the primary source of <strong>in</strong>formationabout adolescent pregnancies. This is sobecause there are ethical challenges <strong>in</strong> collect<strong>in</strong>gdata from this group, especially aboutsensitive issues of sexuality and pregnancies.Therefore, most data about those under age15 are obta<strong>in</strong>ed retrospectively—that is,THE STATE OF WORLD POPULATION 20135

FACING THE CHALLENGE OFADOLESCENT PREGNANCYPERCENTAGE OF WOMEN AGES 20 TO 24WHO REPORTED GIVING BIRTH BY AGE 18(MOST RECENT DATA FROM DEVELOPING COUNTRIES, 1996-2011)Less than 1010–1930 and aboveNo data or <strong>in</strong>complete data20–29Source: www.dev<strong>in</strong>fo.org/mdg5b. Map shows only countries where data weregathered from DHS or MICS surveys.PERCENTAGE OF WOMEN BETWEEN THE AGESOF 20 AND 24 REPORTING A BIRTH BEFORE AGE 18AND BEFORE AGE 15Report<strong>in</strong>g first birth before age 15 Report<strong>in</strong>g first birth before age 18Develop<strong>in</strong>gCountries319West &Central AfricaEast & SouthernAfrica462528South Asia422Lat<strong>in</strong> America &the Caribbean218Arab States110East Asia &PacificEastern Europe& Central Asia1⊳0.2 485 10 15 20 25 30 35Source: UNFPA, 2013. Calculations based on data for 81 countries, represent<strong>in</strong>g more than 83 per cent of the population covered <strong>in</strong>these regions, us<strong>in</strong>g data collected between 1995 and 2011.6 CHAPTER 1: A GLOBAL CHALLENGE

The boundaries and names shownand the designations used onthis map do not imply officialendorsement or acceptance bythe United Nations. Dotted l<strong>in</strong>erepresents approximately theL<strong>in</strong>e of Control <strong>in</strong> Jammu andKashmir agreed upon by Indiaand Pakistan.The f<strong>in</strong>al status of Jammu andKashmir has not yet been agreedupon by the parties.“Efforts—and resources—toprevent adolescent pregnancyhave typically focused on girlsages 15 to 19. Yet, the girls withthe greatest vulnerabilities, andwho face the greatest risk ofcomplications and death frompregnancy and childbirth,are 14 or younger.”BIRTHS BEFORE AGE 15ONE GIRL IN 10has a child before the age of 15 <strong>in</strong>Bangladesh, Chad, Gu<strong>in</strong>ea, Mali,Mozambique and Niger6%Among develop<strong>in</strong>gcountries, Westand Central Africaaccount for the largestpercentage (6 per cent)of reported birthsbefore age 15.THE STATE OF WORLD POPULATION 20137

“I was 12 years old when a man came to askmy parents for my hand <strong>in</strong> marriage. They toldme to marry him and after some time I fell <strong>in</strong>love with him. I have two older brothers. Bothof them went to school, but my parents neverlet me. I don’t know why, maybe because Iam a girl and they knew that I was go<strong>in</strong>g toget married later on. I had my first child whenI was 13 years old. It is not normal but it justhappened. I had problems giv<strong>in</strong>g birth buteveryth<strong>in</strong>g went well. I have three girls andI am pregnant for the fourth time.”Marielle, 25, pregnant at 13, Madagascareither because of social norms concern<strong>in</strong>gage-appropriate behaviours, ethical concernsregard<strong>in</strong>g potentially harmful effects of theresearch, or doubts about the validity of youngadolescents’ responses (Chong et al., 2006).In a report on DHS data concern<strong>in</strong>g adolescentsbetween the ages of 10 and 14, thePopulation Council emphasized the needfor research about important markers of thetransition from childhood to adolescence: “Inreview<strong>in</strong>g these DHS data on very young adolescents,what we ma<strong>in</strong>ly know is that we don’tknow very much.” (Blum et al., 2013)Some researchers question whether veryyoung adolescents have the cognitive ability toanswer questions requir<strong>in</strong>g a thoughtful assessmentof the barriers they face or of potentialconsequences of future actions. Others believethat the stigma surround<strong>in</strong>g premarital sexualactivity for girls is too high to obta<strong>in</strong> accurate<strong>in</strong>formation (Chong et al., 2006).researchers ask women who are between 20 and24 to report the age at which they married andhad their first pregnancy or birth.Ma<strong>in</strong>ta<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g high ethical standards is crucial<strong>in</strong> conduct<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>formation-gather<strong>in</strong>g activities.Children and adolescents require special protections,both because they are vulnerableto exploitation, abuse, and other harmfuloutcomes, and because they have less powerthan adults. Information about school<strong>in</strong>g andgeneral well-be<strong>in</strong>g has long been collected onyoung adolescents, but most researchers haveshied away from cover<strong>in</strong>g sensitive topics,Birth rates vary with<strong>in</strong> countriesAdolescent birth rates often vary with<strong>in</strong> acountry, depend<strong>in</strong>g on a number of variables,such as poverty or the local prevalence ofchild marriage. Niger, for example, has theworld’s highest adolescent birth rate and thehighest child marriage rate overall, but girls<strong>in</strong> the country’s Z<strong>in</strong>der region are more thanthree times as likely to give birth before age 18than their counterparts <strong>in</strong> the nation’s capital,Niamey. Z<strong>in</strong>der is a poor, predom<strong>in</strong>antly ruralregion, where malnutrition is common andaccess to health care is limited.A review of data gathered through DHSand MICS surveys <strong>in</strong> 79 develop<strong>in</strong>g countriesbetween 1998 and 2011 shows that adolescentbirth rates are higher <strong>in</strong> rural areas, among8 CHAPTER 1: A GLOBAL CHALLENGE

adolescents with no education and <strong>in</strong> thepoorest 20 per cent of households.Variations with<strong>in</strong> a country may resultnot only from differences <strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong>comes, butalso from <strong>in</strong>equitable access to educationand sexual and reproductive health services,<strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g contraceptives, the prevalence ofchild marriage, local customs and social pressures,and <strong>in</strong>adequate or poorly enforced lawsand policies.Understand<strong>in</strong>g these differences can helppolicymakers develop <strong>in</strong>terventions that aretailored to the diverse needs of communitiesacross a country.Pregnancies and births amongmarried childrenDespite near-universal commitments to endchild marriage, one <strong>in</strong> three girls <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>gcountries (not <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g Ch<strong>in</strong>a) is marriedbefore age 18 (UNFPA, 2012).Most of these girls are poor, less-educatedand live <strong>in</strong> rural areas. In the next decade, anestimated 14 million child marriages will occurannually <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g countries.Adolescent birth rates are highest where childmarriage is most prevalent, and child marriagesare generally more frequent where poverty isextreme. The prevalence of child marriagetSixteen-year-oldUsha Yadab, classleader for ChooseYour Future, aUNFPA-supportedprogramme <strong>in</strong> Nepalthat teaches girlsabout health issuesand encourages thedevelopment of basiclife skills.©William Ryan/UNFPATHE STATE OF WORLD POPULATION 20139

“All of a sudden the worldbecame a lonely place. I feltexcluded from my familyand the community. I nolonger fitted <strong>in</strong> as a youngperson, nor did I fit <strong>in</strong> asa woman.”Tarisai, 20, pregnant at 16, Zimbabwevaries substantially across countries, rang<strong>in</strong>g from2 per cent <strong>in</strong> Algeria to 75 per cent <strong>in</strong> Niger,which has the world’s fifth-lowest per capitagross national <strong>in</strong>come (World Bank, 2013).While child marriages are decl<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g amonggirls under age 15, 50 million girls could stillbe at risk of be<strong>in</strong>g married before their 15thbirthday <strong>in</strong> this decade.Today, one <strong>in</strong> n<strong>in</strong>e girls <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g countriesis forced <strong>in</strong>to marriage before age 15. InBangladesh, Chad and Niger, more than one <strong>in</strong>three girls is married before her 15th birthday. InEthiopia, one <strong>in</strong> six girls is married by age 15.Age differences with<strong>in</strong> unions or marriagesalso <strong>in</strong>fluence adolescent pregnancy rates.ADOLESCENT BIRTH RATES (DATA FROM 79 COUNTRIES)By RegionBy Background CharacteristicsWest &Central AfricaEast &Southern AfricaLat<strong>in</strong> America& CaribbeanWorldArab States50507923109129Develop<strong>in</strong>gCountriesRuralUrbanNo EducationPrimarySecondaryor Higher565685103119154South AsiaEastern Europe &Central AsiaEast Asia& Pacific0 50 100 150203149PoorestSecondMiddleFourthRichest1181099577420 50 100 150 200Source: UNFPA, 2013.10 CHAPTER 1: A GLOBAL CHALLENGE

A UNFPA review of four countries found thatthe greater the age difference, the greater thechances are that the girl will become pregnantbefore age 18 (United Nations, 2011a).In countries where women tend to marry atyoung ages, the differences between the s<strong>in</strong>gulatemean age at marriage, or SMAM, betweenmales and females are generally large. Thethree countries with the lowest female SMAMsas of 2008 were Niger (17.6 years), Mali (17.8years) and Chad (18.3 years). All had age differencesbetween male and female SMAMs ofat least six years. SMAM is the average lengthof s<strong>in</strong>gle life among persons between ages15 and 49 (United Nations, 2011a).“I was given to my husbandwhen I was little and I don’teven remember when I wasgiven because I was so little.It’s my husband who broughtme up.”Kanas, 18, EthiopiaWOMEN BETWEEN THE AGES OF 20 AND 24 REPORTING A BIRTH BEFOREAGE 18 AND BEFORE AGE 15, 2010 AND PROJECTIONS THROUGH 2030South Asia Sub-Saharan Africa Lat<strong>in</strong> America and the CaribbeanBefore Age 18 Before Age 15254Millions20151017.410.117.9 18.1 18.2 18.414.712.916.411.4Millions322.91.83.0 3.0 3.0 3.03.02.72.42.154.5 4.6 4.7 4.7 4.610.5 0.5 0.5 0.5 0.5002010 2015 2020 2025 2030 2010 2015 2020 2025 2030Source: www.dev<strong>in</strong>fo.org/mdg5bTHE STATE OF WORLD POPULATION 201311

PER CENT OF ADOLESCENT GIRLS IN MARRIAGESAND ADOLESCENT BIRTH RATESGirls, ages 15–19Develop<strong>in</strong>g RegionsCurrently married (%)Adolescent birth rateArab States 12 50Asia and Pacific 15 80East Asia and Pacific 5 50South Asia 25 88Eastern Europe and Central Asia 9 31Lat<strong>in</strong> America and Caribbean 12 84Sub-Saharan Africa 24 120East and Southern Africa 19 112West and Central Africa 28 129Develop<strong>in</strong>g countries 16 85Source: www.dev<strong>in</strong>fo.org/mdg5bPER CENT OF WOMEN REPORTING A FIRST BIRTH BEFORE AGE 18,BY AGE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN PARTNERSAge differences between female and male partners Niger Burk<strong>in</strong>a Faso Bolivia IndiaFemale is older than male partner or up to 4 years younger 39.9 21.5 29.7 21.6Female is between 5 and 9 years younger than male partner 60.1 34.4 41.5 32.3Female is at least 10 years younger than male partner 59.0 38.5 45.8 39.1Total 56.8 33.4 34.7 28.5Source: United Nations, 2011a.12 CHAPTER 1: A GLOBAL CHALLENGE

Developed countries facechallenges tooAdolescent pregnancy occurs <strong>in</strong> both developedand develop<strong>in</strong>g countries. The levelsdiffer greatly, although the determ<strong>in</strong>antsare similar.Of the annual 13.1 million births to girlsages 15 to 19 worldwide, 680,000 occur <strong>in</strong>developed countries (United Nations, 2013).Among developed countries, the UnitedStates has the highest adolescent birth rate.Accord<strong>in</strong>g to the United States Centers forDisease Control and Prevention, 329,772births were recorded among adolescentsbetween 15 and 19 <strong>in</strong> 2011.Among member States of the Organisationfor Economic Co-operation andDevelopment, which <strong>in</strong>cludes a number ofmiddle-<strong>in</strong>come countries, Mexico has thehighest birth rate (64.2 per 1,000 births)among adolescents between 15 and 19 whileSwitzerland ranks the lowest, with 4.3. Allbut one OECD member, Malta, saw adecrease <strong>in</strong> adolescent pregnancy ratesbetween 1980 and 2008.ConclusionMost adolescent pregnancies occur <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>gcountries.Evidence from 54 develop<strong>in</strong>g countries suggeststhat adolescent pregnancies are occurr<strong>in</strong>gwith less frequency, ma<strong>in</strong>ly among girls under15, but the decrease <strong>in</strong> recent years has beenslow. In some regions, the total number ofgirls giv<strong>in</strong>g birth is projected to rise. In sub-Saharan Africa, for example, if current trendscont<strong>in</strong>ue, the number of girls under 15 whogive birth is expected to rise from 2 million ayear today to about 3 million a year <strong>in</strong> 2030.ADOLESCENT FERTILITY RATES IN OECDCOUNTRIES, 1980 AND 2008MexicoChileBulgariaTurkeyUnited StatesLatviaUnited K<strong>in</strong>gdomEstoniaNew ZealandSlovak RepublicHungaryLithuaniaMaltaIrelandPolandPortugalAustraliaIcelandIsraelSpa<strong>in</strong>CanadaGreeceFranceCzech RepublicAustriaGermanyNorwayLuxembourgF<strong>in</strong>landBelgiumCyprusDenmarkSwedenRepublic of KoreaNetherlandsSloveniaItalyJapanSwitzerland2008 19800 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80Source: http://www.oecd.org/social/soc/oecdfamilydatabase.htmTHE STATE OF WORLD POPULATION 201313

ADOLESCENTS AND CHILDREN: DEFINITIONSAND TRENDSAlthough the United Nations def<strong>in</strong>es “adolescent” as anyone betweenthe ages of 10 and 19, most of the <strong>in</strong>ternationally comparable statisticsand estimates that are available on adolescent pregnancies or birthscover only part of the cohort: ages 15 to 19. Far less <strong>in</strong>formation is availablefor the segment of the adolescent population between the ages of10 and 14, yet it is this younger group whose needs and vulnerabilitiesmay be the greatest.Accord<strong>in</strong>g to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, anyone underthe age of 18 is considered a “child.” This report focuses on pregnanciesand births among children but must often rely on data on pregnanciesand births for the larger cohort of adolescents. Data on children (youngerthan 18) who become pregnant are more limited, cover<strong>in</strong>g a little morethan one third of the world’s countries.LARGE AND GROWING ADOLESCENTPOPULATIONSIn 2010, the worldwide number of adolescents was estimated to be1.2 billion, the largest adolescent cohort <strong>in</strong> human history. Adolescentsmake up about 18 per cent of the world’s population. Eighty-eightper cent of all adolescents live <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g countries. About half(49 per cent) of adolescent girls live <strong>in</strong> just six countries: Ch<strong>in</strong>a, India,Indonesia, Nigeria, Pakistan and the United States.If current population growth trends cont<strong>in</strong>ue, by 2030 almost one<strong>in</strong> four adolescent girls will live <strong>in</strong> sub-Saharan Africa where the totalnumber of adolescent mothers under 18 is projected to rise from10.1 million <strong>in</strong> 2010 to 16.4 million <strong>in</strong> 2030.In develop<strong>in</strong>g and developed countries,adolescent pregnancies are more likely to occuramong girls from lower-<strong>in</strong>come households,those with lower levels of education and thoseliv<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> rural areas.Retrospective data on pregnancies are availablefor adolescent girls ages 10 to 14 as wellas those 15 to 19, but much more is knownabout the latter group because householdsurveys reach them directly.Data about pregnancies or births outside ofmarriage are especially scarce. But these dataare crucial to understand<strong>in</strong>g the determ<strong>in</strong>antsof pregnancies among this group, their challengesand vulnerabilities, the impact on theirlives, and on actions that governments, communitiesand families might take to help themprevent pregnancies or support those who havealready become pregnant or given birth.The life trajectories of each pregnant girldepends, however, not only on how youngshe is, but also where she lives, how empoweredshe is through rights and opportunitiesand how much access she has to health care,school<strong>in</strong>g and economic resources. The impactof a pregnancy on a married 14-year-old girl <strong>in</strong>a rural area, for example, is very different fromthat of an 18-year-old who is s<strong>in</strong>gle, lives <strong>in</strong>a city or has access to family support andf<strong>in</strong>ancial resources.More <strong>in</strong>-depth data and contextual <strong>in</strong>formationon patterns, trends and the circumstancesof pregnancy among girls under 18 (andespecially the cohort of adolescents ages 10 to14) would help lay the groundwork for thetarget<strong>in</strong>g of <strong>in</strong>terventions, the formulationof policies and for a deeper understand<strong>in</strong>g ofcauses and consequences, which are complex,multidimensional and extend far beyond the14 CHAPTER 1: A GLOBAL CHALLENGE

ESTIMATING ADOLESCENT PREGNANCY AND BIRTH RATESPrecise data on adolescent pregnancies are scarce. Vital registrationsystems collect <strong>in</strong>formation on births, not pregnancies.Unlike births, pregnancies are generally not reported andaggregated upward to national statistical <strong>in</strong>stitutions. Somepregnancies fail very early, before a woman or girl is aware sheis pregnant. Pregnancies may go undocumented <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>gcountries because adolescents often do not—or cannot—accessantenatal care and thus do not come to the attention of healthcare providers. Pregnancies that end <strong>in</strong> miscarriage or abortion(often performed illegally and clandest<strong>in</strong>ely) are also absentfrom most national databases.Most countries, therefore, rely on <strong>in</strong>formation about births,as a proxy for data on the prevalence of adolescent pregnancy.Estimates of birth rates are <strong>in</strong>variably lower than pregnancyrates. For example, accord<strong>in</strong>g to a 2008 study, the pregnancyrate among adolescents age 15 to age 19 <strong>in</strong> the United Stateswas 68/1,000 while the birth rate was 40/1,000 (Kost andHenshaw, 2013). Pregnancy rates <strong>in</strong>clude miscarriages, abortions,stillbirths, and pregnancies carried to term, while the birthrate <strong>in</strong>cludes only live births.The proxy data that demographers rely on is gathered <strong>in</strong> two ways:• Through a retrospective approach, which asks womenbetween the ages of 20 and 24 if they had had a childat an earlier age, usually before age 18. Data used <strong>in</strong> theretrospective approach and cited <strong>in</strong> this report come fromdemographic and health surveys, or DHS, and multiple <strong>in</strong>dicatorcluster surveys, or MICS, which have been carried out<strong>in</strong> 81 develop<strong>in</strong>g countries.• By calculat<strong>in</strong>g the adolescent birth rate:AdolescentBirth Rate=Total number of live birthsamong girls between theages of 15 and 19DIVIDED BYx 1,000Total number of adolescents betweenthe ages of 15 and 19The retrospective approach yields <strong>in</strong>sights <strong>in</strong>to births togirls before the age of 18, but can also provide <strong>in</strong>sights <strong>in</strong>tobirths to girls younger than 15. The adolescent birth rate,however, <strong>in</strong>cludes only live births to girls between the agesof 15 and 19.sphere of a pregnant girl. But just as important—andjust as limited—are data and<strong>in</strong>sights about the men and boys who father thechildren of adolescent girls.Adolescent pregnancies are not the soleconcern of develop<strong>in</strong>g countries. Hundredsof thousands of them are reported each year<strong>in</strong> high- and middle-<strong>in</strong>come countries, too.But some of the patterns found <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>gcountries are also relevant <strong>in</strong> developed ones:girls who live <strong>in</strong> low-<strong>in</strong>come households, arerural, have less education or have dropped outof school, or who are ethnic m<strong>in</strong>orities, immigrants,or marg<strong>in</strong>alized sub-populations aremore likely to become pregnant. In develop<strong>in</strong>gcountries, most adolescent pregnancies occurwith<strong>in</strong> marriages, while <strong>in</strong> developed countries,they <strong>in</strong>creas<strong>in</strong>gly occur outside of marriage.THE STATE OF WORLD POPULATION 201315

16 CHAPTER 2: THE IMPACT ON GIRLS' HEALTH, EDUCATION AND PRODUCTIVITY

2The impact on girls’health, educationand productivityWhen a girl becomes pregnant orhas a child, her health, education,earn<strong>in</strong>g potential and her entire futuremay be <strong>in</strong> jeopardy, trapp<strong>in</strong>g her <strong>in</strong>a lifetime of poverty, exclusion andpowerlessness.sA 13-year-old fistula patient at a VVF centre <strong>in</strong> Nigeria.© UNFPA/Ak<strong>in</strong>tunde Ak<strong>in</strong>leyeTHE STATE OF WORLD POPULATION 201317

When a girl becomes pregnant or has a child,her health, education, earn<strong>in</strong>g potential and herentire future may be <strong>in</strong> jeopardy, trapp<strong>in</strong>g her <strong>in</strong>a lifetime of poverty, exclusion and powerlessness.The impact on a young mother is often passeddown to her child, who starts life at a disadvantage,perpetuat<strong>in</strong>g an <strong>in</strong>tergenerational cycle ofmarg<strong>in</strong>alization, exclusion and poverty.And the costs of early pregnancy and childbirthextend beyond the girl’s immediate sphere,tak<strong>in</strong>g a toll on her family, the community, theeconomy and the development and growth ofher nation.While pregnancy can affect a girl’s life <strong>in</strong>numerous and profound ways, most quantitativeresearch has focused on the effects on health,education and economic productivity:• The health impact <strong>in</strong>cludes risks of maternaldeath, illness and disability, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g obstetricfistula, complications of unsafe abortion, sexuallytransmitted <strong>in</strong>fections, <strong>in</strong>clud<strong>in</strong>g HIV, andhealth risks to <strong>in</strong>fants.• The educational impact <strong>in</strong>cludes the <strong>in</strong>terruptionor term<strong>in</strong>ation of formal education andthe accompany<strong>in</strong>g lost opportunities to realizeone’s full potential.• The economic impact is closely l<strong>in</strong>ked to theeducational impact and <strong>in</strong>cludes the exclusionfrom paid employment or livelihoods, additionalcosts to the health sector and the lossof human capital.Health impactAbout 70,000 adolescents <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g countriesdie annually of causes related to pregnancyand childbirth (UNICEF, 2008). Complicationsof pregnancy and childbirth are a lead<strong>in</strong>g causeof death for older adolescent females (WorldHealth Organization, 2012).Adolescents who become pregnant tend to befrom lower-<strong>in</strong>come households and be nutritionallydepleted. Although rates vary by region,overall, approximately one <strong>in</strong> two girls <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>gcountries has nutritional anaemia, whichHortência, 25,developed anobstetric fistulaat 17, dur<strong>in</strong>g acomplicated delivery.© UNFPA/Pedro Sá daBandeirat18 CHAPTER 2: THE IMPACT ON GIRLS' HEALTH, EDUCATION AND PRODUCTIVITY

can <strong>in</strong>crease the risk of miscarriage, stillbirth,premature birth and maternal death (Pathf<strong>in</strong>derInternational, 1998; Balarajan et al., 2011;Ransom and Elder, 2003).A number of factors directly contribute tomaternal death, illness and disability amongadolescents. These <strong>in</strong>clude the girl’s age, herphysical immaturity, complications from unsafeabortion and lack of access to rout<strong>in</strong>e and emergencyobstetric care from skilled providers. Othercontribut<strong>in</strong>g factors <strong>in</strong>clude poverty, malnutrition,lack of education, child marriage and thelow status of girls and women (World HealthOrganization, 2012b).Health problems are more likely if a girlbecomes pregnant with<strong>in</strong> two years of menarcheor when her pelvis and birth canal are still grow<strong>in</strong>g(World Health Organization, 2004).Obstetric fistulaPhysically immature first-time mothers are particularlyvulnerable to prolonged, obstructed labour,which may result <strong>in</strong> obstetric fistula, especiallyif an emergency Caesarean section is unavailableor <strong>in</strong>accessible. Although fistula can occurto women at any reproductive age, studies <strong>in</strong>Ethiopia, Malawi, Niger and Nigeria show thatabout one <strong>in</strong> three women liv<strong>in</strong>g with obstetricfistula reported develop<strong>in</strong>g it as an adolescent(Muleta et al., 2010; Tahzib, 1983; Hilton andWard, 1998; Kelly and Kwast, 1993; Ibrahim etal., 2000; Rijken and Chilopora, 2007).Obstetric fistula is a debilitat<strong>in</strong>g condition thatrenders a woman <strong>in</strong>cont<strong>in</strong>ent and, <strong>in</strong> most cases,results <strong>in</strong> a stillbirth or the death of the babywith<strong>in</strong> the first week of life.Between 2 million and 3.5 million women andgirls <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g countries are thought to beliv<strong>in</strong>g with the condition. In many <strong>in</strong>stances, aOBSTETRIC FISTULA: ANOTHER BLIGHT ON THECHILD BRIDEIt was personal experience that turned Gul Bano and her cleric husband,Ahmed Khan, <strong>in</strong>to ambassadors aga<strong>in</strong>st early marriage and itsworst corollary—obstetric fistula.As is the custom <strong>in</strong> the remote mounta<strong>in</strong> village of Kohadast <strong>in</strong> theKhuzdar district of Balochistan prov<strong>in</strong>ce <strong>in</strong> Pakistan, Bano was marriedoff as soon as she reached adolescence, at 15, and was pregnant thefollow<strong>in</strong>g year.There be<strong>in</strong>g no healthcare facility near Kohadast, Bano did notreceive antenatal care and no one thought there would be complications.But, events were to prove different. After an extended labourlast<strong>in</strong>g three days, Bano delivered a dead baby. “I never saw the colourof my son’s eyes or his hair. I never held him once to my bosom,” recallsBano, now 20.Her troubles had only begun. A week later, Bano realized she wasalways wet with ur<strong>in</strong>e and reek<strong>in</strong>g of fecal matter. “I was pass<strong>in</strong>g ur<strong>in</strong>eand stools together.”Unable to handle the prolonged labour, Bano’s young body haddeveloped an obstetric fistula caused by the baby’s head press<strong>in</strong>g hardaga<strong>in</strong>st the l<strong>in</strong><strong>in</strong>g of the birth canal and tear<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong>to the walls of herrectum and the bladder.Obstetric fistula is now generally acknowledged to be anotherburden on the girl child, deprived of basic education and forced <strong>in</strong>tomarriage—for which she is neither physically nor mentally prepared.Khan stood by his young wife and sought medical help. He discovereda hospital <strong>in</strong> Karachi specializ<strong>in</strong>g <strong>in</strong> treat<strong>in</strong>g fistula and other conditionsrelated to reproductive health. Koohi Goth Women’s Hospital, wherefistula victims are treated free, was started by Dr. Shershah Syed, oneof Pakistan’s first gynaecologists to tra<strong>in</strong> <strong>in</strong> repair<strong>in</strong>g the pa<strong>in</strong>ful andsocially embarrass<strong>in</strong>g condition.“It’s been almost three years and she [Bano] has gone through sixoperations,” says Dr. Sajjad Ahmed, who worked at Koohi Goth as managerof UNFPA’s fistula project from June 2006 to February 2010.Today Bano and Khan have become vocal advocates of the campaignaga<strong>in</strong>st fistula. They travel across Pakistan, spread<strong>in</strong>g the word abouthow to prevent the <strong>in</strong>jury and what to do about it. “Khan is a cleric andyet he does not conform to the stereotype of a religious person,” saidSyed. “He tells parents that fistula can be avoided if they stop marry<strong>in</strong>goff their daughters at a very early age.” Bano shares her story andtells married women about the importance of birth spac<strong>in</strong>g, antenatalcheckups and timely access to emergency obstetric care.—Zofeen Ebrahim, Inter Press ServiceTHE STATE OF WORLD POPULATION 201319

Develop<strong>in</strong>g regionswoman—or girl—liv<strong>in</strong>g with obstetric fistula isostracized from her home and her communityand is at risk of poverty and marg<strong>in</strong>alization.The persistence of obstetric fistula is a reflectionof chronic health <strong>in</strong>equities and health-caresystem constra<strong>in</strong>ts, as well as wider challenges,such as gender and socio-economic <strong>in</strong>equality,child marriage and early child bear<strong>in</strong>g, all ofwhich can underm<strong>in</strong>e the lives of women andgirls and <strong>in</strong>terfere with their enjoyment of theirbasic human rights.In most cases, fistula can be repaired throughsurgery, but few actually undergo the procedure,ma<strong>in</strong>ly because services are not widely availableor accessible, especially <strong>in</strong> poor countries lack<strong>in</strong>gquality medical services and <strong>in</strong>frastructure,or because the surgery, which can cost as little as$400, is prohibitively expensive for most womenand girls <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g countries. Of the 50,000to 100,000 new cases per year, only about 14,000undergo surgery, so the total number of womenliv<strong>in</strong>g with the condition rises every year.While a skilled birth attendant and emergencyCaesarean section can help an adolescent avertobstetric fistula, the best way to protect a girlESTIMATES OF UNSAFE ABORTIONS AND UNSAFEABORTION RATES FOR GIRLS, AGES 15 TO 19, 2008Annual numberof unsafeabortions togirls 15–19Unsafe abortionrate (per 1,000girls 15–19)Develop<strong>in</strong>g countries 3,200,000 16Africa 1,400,000 26Asia exclud<strong>in</strong>g East Asia 1,100,000 9Lat<strong>in</strong> America and the Caribbean 670,000 25Source: Shah and Ahman, 2012.from the condition is to help her delay pregnancyuntil she is older and her body matures. Oftenthis means protect<strong>in</strong>g her from early marriage.Unsafe abortionUnsafe abortions account for almost half ofall abortions (Sedgh et al., 2012; Shah andAhman, 2012). Accord<strong>in</strong>g to the World HealthOrganization, an unsafe abortion is “a procedurefor term<strong>in</strong>at<strong>in</strong>g unwanted pregnancy eitherby persons lack<strong>in</strong>g the necessary skills or <strong>in</strong> anenvironment lack<strong>in</strong>g m<strong>in</strong>imal medical standardsor both” (World Health Organization, 2012c).Almost all (98 per cent) of the unsafe abortionstake place <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g countries, where abortionis often illegal. Even where abortion is legal,adolescents may f<strong>in</strong>d it difficult to access services.Data on abortions, safe or unsafe, for girlsbetween the ages of 10 and 14 <strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>gcountries are scarce but rough estimates havebeen made for the 15 to 19 age group, whichaccounts for about 3.2 million unsafe abortions<strong>in</strong> develop<strong>in</strong>g countries each year (Shah andAhman, 2012).This study covers Africa, Asia (exclud<strong>in</strong>gEast Asia) and Lat<strong>in</strong> America and the Caribbean(Shah and Ahman, 2012). Rates of unsafe abortionsper 1,000 are similar for sub-SaharanAfrica and Lat<strong>in</strong> America and the Caribbean:26 versus 25, respectively; however, the totalnumber of unsafe abortions <strong>in</strong> sub-SaharanAfrica is more than double that of Lat<strong>in</strong> Americaand the Caribbean, because of the former’s largerpopulation size. Sub-Saharan Africa accountsfor 44 per cent of all unsafe abortions amongadolescents between the ages of 15 and 19 <strong>in</strong> thedevelop<strong>in</strong>g world (exclud<strong>in</strong>g East Asia), whileLat<strong>in</strong> America and the Caribbean account for23 per cent.20 CHAPTER 2: THE IMPACT ON GIRLS' HEALTH, EDUCATION AND PRODUCTIVITY

In sub-Saharan Africa, an estimated 36,000women and girls die each year from unsafe abortion,and millions more suffer long-term illnessor disability (UN Radio, 2010).Compared to adults who have unsafe abortions,adolescents are more likely to experiencecomplications such as haemorrhage, septicaemia,<strong>in</strong>ternal organ damage, tetanus, sterility and evendeath (International Sexual and ReproductiveRights Coalition, 2002). Some explanations forworse health outcomes for adolescents are thatthey are more likely to delay seek<strong>in</strong>g and hav<strong>in</strong>gan abortion, resort to unskilled persons toperform it, use dangerous methods and delayseek<strong>in</strong>g care when complications arise.Adolescents make up a large proportion ofpatients hospitalized for complications of unsafeabortions. In some develop<strong>in</strong>g countries, hospitalrecords suggest that between 38 per cent and68 per cent of those treated for complicationsof abortion are adolescents (International Sexualand Reproductive Rights Coalition, 2002).“I have accepted myHIV status because whensometh<strong>in</strong>g has happened,it has happened.”Neo, 15, BotswanaPERCENTAGE OF GIRLS, AGES 15 TO 19, WHO EVERHAD SEXUAL INTERCOURSE AND REPORTED ANSTI OR SYMPTOMS IN THE PAST 12 MONTHS(COUNTRIES WITH 20 PER CENT OR MORE)Gu<strong>in</strong>eaGhanaCongo, Republic ofNicaraguaCôte d’IvoireDom<strong>in</strong>ican RepublicUgandaSource: Kothari et al., 2012.Sexually transmitted <strong>in</strong>fectionsWorldwide each year, there are 340 millionnew sexually transmitted <strong>in</strong>fections, or STIs.Youth between the ages of 15 and 24 have thehighest rates of STIs. Although STIs are not aconsequence of adolescent pregnancy, they area consequence of sexual behaviour—non-use or<strong>in</strong>correct use of condoms—that may lead to adolescentpregnancy. If untreated, STIs can cause<strong>in</strong>fertility, pelvic <strong>in</strong>flammatory disease, ectopicpregnancy, cancer, and debilitat<strong>in</strong>g pelvic pa<strong>in</strong>for women and girls. They may also lead to lowbirth-weight babies, premature deliveries andlife-long physical and neurological conditions forchildren born to mothers liv<strong>in</strong>g with STIs.In seven of 35 countries covered <strong>in</strong> a recentreview of demographic and health surveys, at leastone <strong>in</strong> five female adolescents between the ages of15 and 19 who ever had sexual <strong>in</strong>tercourse <strong>in</strong>dicatedthat they had an STI or symptoms of one<strong>in</strong> the past 12 months (Kothari et al., 2012).35 per cent29 per cent29 per cent26 per cent25 per cent21 per cent21 per centTHE STATE OF WORLD POPULATION 201321

Demographic and health surveys show that,<strong>in</strong> general, the percentage of females betweenthe ages of 15 and 19 who ever had sex andwho reported STIs or symptoms <strong>in</strong> the past 12months is higher than that reported by malesHIV PREVALENCE AMONG ADOLESCENTS AGES15 TO 19, BY SEX, IN SELECTED SUB-SAHARANAFRICAN COUNTRIES, 2001–2007MaleFemaleSenegal 2005Ghana 2003Mali 2006Rwanda 2005Ethiopia 2005Burk<strong>in</strong>a Faso 2003Gu<strong>in</strong>ea 2005Liberia 2007United Republic ofTanzania 2007–08Cameroon 2004Uganda 2004–05Kenya 2003Zambia 2007–08Zimbabwe 2005–06Lesotho 2004Swaziland 2006–07Source: World Health Organization, 2009a.0246Adolescents aged 15–19 years liv<strong>in</strong>g with HIV (%)81012who ever had sex <strong>in</strong> that same age group. InCôte d’Ivoire, for example, 25 per cent of femalesbetween 15 and 19 and who had ever had sexreported an STI or symptoms of one comparedto 14 per cent of males <strong>in</strong> the same age group.Other studies of STIs and adolescents alsoshow that girls are more frequently affected thanboys (Dehne and Riedner, 2005). STIs are commonamong sexually assaulted adolescents andabused children.Adolescent girls are also more likely than boysto be liv<strong>in</strong>g with HIV. Young women are morevulnerable to HIV <strong>in</strong>fection because of biologicalfactors, hav<strong>in</strong>g older sex partners, lack of accessto <strong>in</strong>formation and services and social norms andvalues that underm<strong>in</strong>e their ability to protectthemselves. Their vulnerability may <strong>in</strong>crease dur<strong>in</strong>ghumanitarian crises and emergencies wheneconomic hardship can lead to <strong>in</strong>creased risk ofexploitation, such as traffick<strong>in</strong>g, and <strong>in</strong>creasedreproductive health risks related to the exchangeof sex for money and other necessities (WorldHealth Organization, 2009a).Health risks to <strong>in</strong>fants and childrenThe health risks to the <strong>in</strong>fants and children ofadolescent mothers have been well documented.Stillbirths and newborn deaths are 50 per centhigher among <strong>in</strong>fants of adolescent mothersthan among <strong>in</strong>fants of mothers between theages of 20 and 29 (World Health Organization,2012a). About 1 million children born to adolescentmothers do not make it to their firstbirthday. Infants who survive are more likely tobe of low birth weight and be premature thanthose born to women <strong>in</strong> their 20s. In addition,without a mother’s access to treatment, thereis a higher risk of mother-to-child transmissionof HIV.22 CHAPTER 2: THE IMPACT ON GIRLS' HEALTH, EDUCATION AND PRODUCTIVITY