a Tribute to - Poetry Society of America

a Tribute to - Poetry Society of America

a Tribute to - Poetry Society of America

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

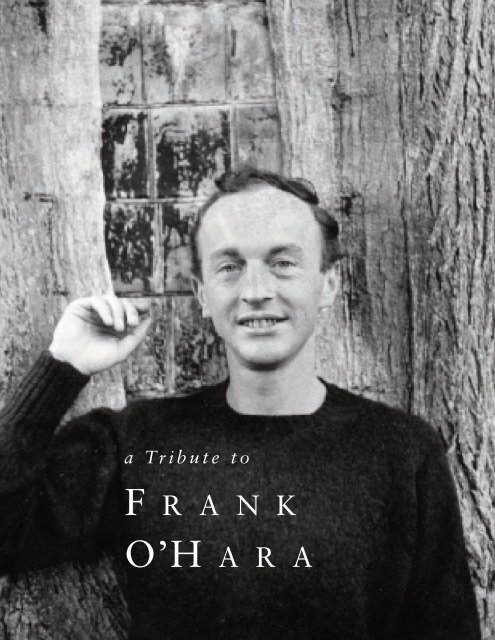

a Tr i b u t e t o<br />

F R A N K<br />

O’H A R A

Homage<br />

Poets Discuss<br />

Their Favorite<br />

Frank O’Hara<br />

Poems<br />

Memorial Day 1950<br />

—John Ashbery<br />

I<br />

’ve always felt a special connection <strong>to</strong> Frank’s “Memorial<br />

.Day 1950.” For one thing, I rescued it from oblivion. It<br />

wasn’t in his papers when he died. Then I remembered I had<br />

once typed it out in a letter <strong>to</strong> Kenneth Koch when he was in<br />

France on a Fulbright. I had been trying <strong>to</strong> persuade<br />

Kenneth, who at that time was insisting that he and I were<br />

the only important young <strong>America</strong>n poets, <strong>to</strong> include Frank<br />

in our mini-cenacle, and sent him Frank’s poems in an effort<br />

<strong>to</strong> convince him. I was successful since Kenneth returned<br />

persuaded and kept the letter in his files.<br />

I first read the poem in the summer <strong>of</strong> 1950 (I assume it had<br />

been written on Memorial Day <strong>of</strong> that year), on a trip <strong>to</strong> visit<br />

Frank in Bos<strong>to</strong>n. He was staying in a house on the back <strong>of</strong><br />

Beacon Hill that belonged <strong>to</strong> his friend Cervin (“Cerv”)<br />

Robinson’s family, who were away. I had graduated from<br />

Harvard in 1949 and was living in New York. Frank, though<br />

a year older than I, graduated in 1950 since he had spent two<br />

years in the Navy during the war. I was missing him and<br />

Bos<strong>to</strong>n, and I remember our going <strong>to</strong> lots <strong>of</strong> movies (“Panic<br />

in the Streets” and Olivier’s “Hamlet” among them) and<br />

drinking zombies (a newly invented drink, I think) at a bar<br />

near the State House. I <strong>to</strong>o stayed at the Robinsons’ and<br />

remember admiring Frank’s room for the kind <strong>of</strong> Spartan<br />

chic he always managed <strong>to</strong> create around him. The room<br />

4<br />

looked out on a courtyard <strong>of</strong> trees and was practically bare<br />

except for an army cot and blanket and a frying pan on the<br />

floor, used as an ashtray, an idea he got from George<br />

Montgomery, a sort <strong>of</strong> arbiter <strong>of</strong> Spartan chic who had been<br />

at Harvard with us. Hence, no doubt, the line: “How many<br />

trees and frying pans I’ve loved and lost.” There were<br />

probably reproductions from MOMA and maybe a clay<br />

candelabra, but I don’t remember them.<br />

The poem’s aggressively modernist <strong>to</strong>ne may seem a little<br />

dated <strong>to</strong>day, but at the time such figures as Max Ernst,<br />

Gertrude Stein, Boris Pasternak, Paul Klee, Auden and<br />

Rimbaud were far from being accepted cultural icons, at least<br />

in the world <strong>of</strong> Bos<strong>to</strong>n-Cambridge. (The year before, Frank<br />

and I had attended a concert that featured the premier <strong>of</strong><br />

Schoenberg’s String Trio. We both loved it, but I remember<br />

Frank getting in<strong>to</strong> an argument with a young member <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Harvard music faculty who insisted that Schoenberg was<br />

literally crazy, and that Frank was <strong>to</strong>o for liking him.)<br />

If his truculent modernist stance, through no fault <strong>of</strong> his,<br />

inevitably seems old-fashioned <strong>to</strong>day, his political<br />

incorrectness, as illustrated in the passage about the sewage<br />

singing under his bright white <strong>to</strong>ilet seat, was decades ahead<br />

<strong>of</strong> its time.<br />

To paraphrase his Lana Turner poem: “oh Frank O’Hara we<br />

love you get up.”

from Memorial Day 1950 1<br />

Picasso made me <strong>to</strong>ugh and quick, and the world;<br />

just as in a minute plane trees are knocked down<br />

outside my window by a crew <strong>of</strong> crea<strong>to</strong>rs.<br />

Once he got his axe going everyone was upset<br />

enough <strong>to</strong> fight for the last ditch and heap<br />

<strong>of</strong> rubbish.<br />

Through all that surgery I thought<br />

I had a lot <strong>to</strong> say, and named several last things<br />

Gertrude Stein hadn’t had time for; but then<br />

the war was over, those things had survived<br />

and even when you’re scared art is no dictionary.<br />

Max Ernst <strong>to</strong>ld us that.<br />

How many trees and frying pans<br />

I loved and lost! Guernica hollered look out!<br />

but we were all busy hoping our eyes were talking<br />

<strong>to</strong> Paul Klee. My mother and father asked me and<br />

I <strong>to</strong>ld them from my tight blue pants we should<br />

love only the s<strong>to</strong>nes, the sea, and heroic figures.<br />

Wasted child! I’ll club you on the shins! I<br />

wasn’t surprised when the older people entered<br />

my cheap hotel room and broke my guitar and my can<br />

<strong>of</strong> blue paint.<br />

At that time all <strong>of</strong> us began <strong>to</strong> think<br />

with our bare hands and even with blood all over<br />

them, we knew vertical from horizontal, we never<br />

smeared anything except <strong>to</strong> find out how it lived.<br />

Fathers <strong>of</strong> Dada! You carried shining erec<strong>to</strong>r sets<br />

in your rough bony pockets, you were generous<br />

and they were lovely as chewing gum or flowers!<br />

Thank you! […]<br />

The Dirty Poems<br />

<strong>of</strong> Frank O’Hara<br />

—Elaine Equi<br />

Ihave always found the idea that poetry should be uplifting<br />

.a depressing one. Our ideal self is our most boring self,<br />

except perhaps as a study in how far we will go <strong>to</strong> maintain<br />

clean hands, a clear conscience and an unequivocal<br />

demarcation between our nobler (or at least our more<br />

politically correct) instincts and our baser ones.<br />

1 All citations from Collected Poems by Frank O’Hara. Copyright © 1971 by Maureen Granville-Smith,<br />

Administratix <strong>of</strong> the Estate <strong>of</strong> Frank O’Hara. Reprinted by permission <strong>of</strong> Alfred A. Knopf, a Division <strong>of</strong><br />

Random House, Inc.<br />

A T R I B U T E T O F R A N K O ’ H A R A<br />

5<br />

For the most part, “negative” emotions such as greed, envy,<br />

cruelty or pettiness are rarely allowed in poetry except as bad<br />

guys <strong>to</strong> be killed <strong>of</strong>f, then transcended. Occasionally, a poet<br />

(particularly a confessional poet) will confess <strong>to</strong> them, but<br />

always with a sense that he or she has sinned. Unfortunately<br />

even lust, with its blatant objectification <strong>of</strong> the other, no<br />

longer seems quite acceptable.<br />

Of course, not all poetry makes human emotion the focal<br />

point <strong>of</strong> its content. But even in more abstract and<br />

experimental styles, poets <strong>of</strong>ten assume the moral<br />

high-ground <strong>of</strong> being set apart from the world <strong>of</strong> industry,<br />

ambition and back-stabbing aggression.<br />

Perhaps that is why, when looking over all <strong>of</strong> Frank O’Hara’s<br />

most impressive body <strong>of</strong> work, I keep returning <strong>to</strong> the two<br />

following rather modest lyrics on “dirt” and “hate.” First <strong>of</strong><br />

all, consider how amazing it is <strong>to</strong> even find “dirt” in a poem.<br />

Easily, nonchalantly, it locates us within the urban experience.<br />

In poems ex<strong>to</strong>lling nature, one finds “earth.” In the<br />

country, there is rich “loam.” But in Frank O’Hara (and in<br />

New York City) one finds simple and unpretentious dirt. Dirt<br />

is pollution, the inevitable by-product <strong>of</strong> commerce. And in<br />

poetry, commerce (as we know) is a dirty word. Yet here<br />

there is no need <strong>to</strong> separate the two worlds. In fact, it<br />

would be impossible <strong>to</strong> do so. “You don’t refuse <strong>to</strong><br />

breathe do you”?<br />

Dirt is also slang for gossip, dish, the juicy lowdown. Dirt,<br />

like talk, is cheap. This connotation <strong>of</strong> the word seems<br />

exceedingly appropriate in helping <strong>to</strong> characterize O’Hara’s<br />

style and contribution <strong>to</strong> contemporary poetry. In his work,<br />

he gossiped about everything from artists and parties <strong>to</strong> the<br />

weather, creating an aura <strong>of</strong> intimacy, excitement and expectation<br />

around whatever he chose <strong>to</strong> discuss. Today we have<br />

the tabloids <strong>to</strong> satisfy our prodigious appetite for dirt. But<br />

perhaps, if we were less threatened by our own ambiguity,<br />

the need <strong>to</strong> vilify others wouldn’t be quite so strong.<br />

In “Song” the literal and figurative qualities <strong>of</strong> dirt morph<br />

in<strong>to</strong> a single character familiar <strong>to</strong> all <strong>of</strong> us: the bad influence<br />

(“attractive as his character is bad”). It is typical <strong>of</strong> O’Hara<br />

that the poem, in its way, celebrates the whole idea <strong>of</strong> bad<br />

influences, finding them <strong>to</strong> be both seductive and necessary—<br />

even educational (“is the character less bad. no. it improves<br />

constantly”). Obviously, Frank is ready and willing <strong>to</strong> avail<br />

himself <strong>of</strong> this and, we may assume, many other bad<br />

influences. True, he was writing in the ’50s and ’60s when<br />

smoking, drinking and promiscuity all seemed more sensible

modes <strong>of</strong> behavior, but the underlying message <strong>of</strong> finding<br />

nothing pure or uncompromised has wider applications.<br />

While hinting at a sexual encounter, the poem itself is about<br />

those things.<br />

In “Poem” on the other hand, Frank assumes the role <strong>of</strong> bad<br />

influence by encouraging the person he’s addressing, as well<br />

as the reader, <strong>to</strong> experience (actually, enjoy) darker emotions<br />

such as hate, unkindness and selfishness. Surprisingly, it turns<br />

out <strong>to</strong> be a sweet and gentle poem <strong>of</strong> assurance that one need<br />

not always be good in order <strong>to</strong> be loved.<br />

I must admit that this has always been a favorite poem. Poets<br />

look <strong>to</strong> other, more well-known poets for permission—and<br />

for me, this permission feels retroactively cus<strong>to</strong>m made. To a<br />

woman who is tired <strong>of</strong> being passive and nurturing, and <strong>to</strong> a<br />

poet who is tired <strong>of</strong> being sensitive, and finally <strong>to</strong> someone<br />

who is just plain tired, living in our relentlessly competitive<br />

and upbeat times, it <strong>of</strong>fers relief. “Don’t be shy <strong>of</strong> unkindness,<br />

either/ it’s cleansing and allows you <strong>to</strong> be direct.”<br />

O’Hara is also a great one for mocking the heroic notion<br />

that artists feel more deeply than your average individual<br />

and suffer more because <strong>of</strong> it. “Think <strong>of</strong> filth, is it really<br />

awesome/ Neither is hate.” Absurd as the idea <strong>of</strong> “poet<br />

as Designated Empath” sounds, variations <strong>of</strong> it continue<br />

<strong>to</strong> live in the public imagination <strong>of</strong> what a poet is and<br />

does. That’s why refusing <strong>to</strong> take such notions seriously<br />

is still a radical step.<br />

Art stays art by maintaining strict borders between itself and<br />

the rest <strong>of</strong> life. Like Duchamp who came before him, and<br />

Andy Warhol who came after him, Frank O’Hara, whether<br />

intentionally or not, is one <strong>of</strong> the figures who questioned and<br />

minimized borders. In the sacred temple <strong>of</strong> fifties art,<br />

O’Hara’s work was like a window that let in, not only fresh<br />

air, but also dirt.<br />

Maybe if the battle between high and low culture had ended<br />

back then, Frank’s poems might be merely interesting or just<br />

terribly entertaining <strong>to</strong> us <strong>to</strong>day. They would have served<br />

their purpose. Instead, when I reread them, they strike me<br />

with a now-more-than-ever vitality.<br />

Art is not so easily democratized. It continues <strong>to</strong> seek new<br />

ways <strong>to</strong> reclaim its privileged status and frighten worshippers<br />

in<strong>to</strong> hushed subservience. But if there is a way <strong>to</strong> be both an<br />

aesthete and a populist, Frank O’Hara found it.<br />

A T R I B U T E T O F R A N K O ’ H A R A<br />

6<br />

In addition <strong>to</strong> the great pleasure his work gives, it also<br />

teaches a valuable lesson. Thanks <strong>to</strong> him, when art becomes<br />

religion (whether <strong>of</strong> the traditional or avant-garde variety), I<br />

know what <strong>to</strong> do. I light a candle <strong>to</strong> dirt.<br />

Poem<br />

Hate is only one <strong>of</strong> many responses<br />

true, hurt and hate go hand in hand<br />

but why be afraid <strong>of</strong> hate, it is only there<br />

think <strong>of</strong> filth, is it really awesome<br />

neither is hate<br />

don’t be shy <strong>of</strong> unkindness, either<br />

it’s cleansing and allows you <strong>to</strong> be direct<br />

like an arrow that feels something<br />

out and out meanness, <strong>to</strong>o, lets love breathe<br />

you don’t have <strong>to</strong> fight <strong>of</strong>f getting in <strong>to</strong>o deep<br />

you can always get out if you’re not <strong>to</strong>o scared<br />

an ounce <strong>of</strong> prevention’s<br />

enough <strong>to</strong> poison the heart<br />

don’t think <strong>of</strong> others<br />

until you have thought <strong>of</strong> yourself, are true<br />

all <strong>of</strong> these things, if you feel them<br />

will be graced by a certain reluctance<br />

and turn in<strong>to</strong> gold<br />

if felt by me, will be smilingly deflected<br />

by your mysterious concern<br />

Song<br />

Is it dirty<br />

does it look dirty<br />

that’s what you think <strong>of</strong> in the city<br />

does it just seem dirty<br />

that’s what you think <strong>of</strong> in the city<br />

you don’t refuse <strong>to</strong> breathe do you<br />

someone comes along with a very bad character<br />

he seems attractive. is he really. yes. very<br />

he’s attractive as his character is bad. is it. yes<br />

that’s what you think <strong>of</strong> in the city<br />

run your finger along your no-moss mind<br />

that’s not a thought that’s soot<br />

and you take a lot <strong>of</strong> dirt <strong>of</strong>f someone<br />

is the character less bad. no. it improves constantly<br />

you don’t refuse <strong>to</strong> breathe do you

True Accounts<br />

—Mark Doty<br />

There are moments in any artistic life when it seems<br />

validation will never come from without, and that all<br />

one’s striving and laboring haven’t the least thing <strong>to</strong> do with<br />

whether anybody ever sees one’s work. When this crisis <strong>of</strong><br />

belief becomes acute, it becomes necessary <strong>to</strong> minister <strong>to</strong><br />

one’s own needs, <strong>to</strong> award oneself some form <strong>of</strong> recognition.<br />

Nobody ever did so more good-humoredly and graciously<br />

than Frank O’Hara, the second poet ever <strong>to</strong> be directly<br />

addressed by the sun.<br />

The first writer that luminary chose “<strong>to</strong> speak <strong>to</strong> personally”<br />

was Vladimir Mayakovsky. In 1920’s “An Extraordinary<br />

Adventure Which Happened <strong>to</strong> Me, Vladimir Mayakovsky,<br />

One Summer in the Country,” the Russian Modernist tells us<br />

exactly where he is—“Pushkino, Mount Akula, Rumyantsev<br />

Cottage, 20 miles down the Yaroslav Railway”—when he<br />

yells an invitation <strong>to</strong> a sun whose predictability he’s grown<br />

weary <strong>of</strong>. Naturally, he doesn’t expect an answer when he<br />

shouts (in Herbert Marshall’s translation):<br />

Listen, golden brightbrow,<br />

instead <strong>of</strong> vainly<br />

setting in the air,<br />

have tea with me<br />

right now!<br />

But the sun, “<strong>of</strong> his own goodwill,” takes the poet up on his<br />

invitation, comes in<strong>to</strong> the garden, banking his fires, and then<br />

right in<strong>to</strong> the house, ready for tea and jam. Before long poet<br />

and fireball are clapping each other on the back, and the sun<br />

is comparing their vocations:<br />

Why, comrade, we’re a pair!<br />

Come, poet,<br />

let us dawn<br />

and sing<br />

away the drabness <strong>of</strong> the universe.<br />

A T R I B U T E T O F R A N K O ’ H A R A<br />

7<br />

But where these two seem like a couple <strong>of</strong> drinking buddies,<br />

all bluster and conviviality, there’s something far subtler at<br />

work in the visitation that same heavenly body makes <strong>to</strong><br />

Frank O’Hara, asleep in a summer house on Fire Island,<br />

thirty-some years later. O’Hara unabashedly allows the sun<br />

<strong>to</strong> come <strong>to</strong> him, and that big Russian roar is replaced by<br />

something less ferocious than petulant, albeit steady and<br />

warm. When he asks the barely awake Frank, “You may be/<br />

wondering why I’ve come so close?” this sun’s character is<br />

clinched—polite, conspira<strong>to</strong>rial, friendly albeit capable <strong>of</strong><br />

hauteur, and bearing a distinct message.<br />

A message launched by a deliciously shameless pun: “Frankly<br />

I wanted <strong>to</strong> tell you/ I like your poetry.” Imagine the potential<br />

pitfalls facing a poem <strong>of</strong> self-praise, a poem intended <strong>to</strong><br />

cheer oneself up about one’s own artistic achievement!<br />

O’Hara’s brilliant solution is not only <strong>to</strong> put the praise in<br />

someone else’s mouth, but <strong>to</strong> make it funny from the first<br />

word and then <strong>to</strong> keep it appealingly qualified through the<br />

sun’s decided unwillingness <strong>to</strong> inflate the poet’s accomplishment:<br />

“I see a lot/ on my rounds and you’re okay. You may/<br />

not be the greatest thing on earth….”<br />

Now the poem begins <strong>to</strong> swim in<strong>to</strong> deeper waters, as the sun<br />

turns <strong>to</strong> increasingly lovely stanzas <strong>of</strong> advice, delivered in a<br />

colloquial <strong>to</strong>ne that keeps his principles, so <strong>to</strong> speak, down<br />

<strong>to</strong> earth. It’s here that the poet is given his highest<br />

compliment: “And now that you/ are making your own days,<br />

so <strong>to</strong> speak,/ even if no one reads you but me/ you won’t be<br />

depressed.” Even if a human gaze doesn’t fall on these<br />

poems, sunlight always will. But now the poet doesn’t even<br />

need that external light; he is “making his own days.” He’s<br />

become a source <strong>of</strong> illumination, one that warms and orders<br />

the world. Mayakovsky says that both his mot<strong>to</strong> and the<br />

sun’s is “always <strong>to</strong> shine,” and here O’Hara shares that<br />

identification, poet and sun aligned in vocation.<br />

Characteristically, the heightened nature <strong>of</strong> this moment is<br />

undercut by O’Hara’s swooning exclamation, and the sun’s<br />

comic response. But just as we’re imagining a talkative sun<br />

fitting himself between Manhattan avenues, the sun bursts<br />

forth with a rhe<strong>to</strong>rical flight <strong>of</strong> startling gravity; it is a call<br />

for a kind <strong>of</strong> generous and detached tenderness <strong>to</strong>wards the<br />

world which one can’t quite imagine O’Hara having been<br />

able <strong>to</strong> make without his gleaming solar mask in place.<br />

That tiny poem left in Frank’s brain might have been quite<br />

enough <strong>to</strong> end “A True Account” on a note <strong>of</strong> graceful<br />

charm, but there is a further distance <strong>to</strong> travel. If this poem

is O’Hara at his warmest, it is also finally as resonant and<br />

strange as a good dream. Whoever calls the sun also calls the<br />

poet; it as if the poem’s pointed <strong>to</strong> voices and forces beyond<br />

its cosmic theater, raising its own stakes. Suddenly the sun<br />

seems a kind <strong>of</strong> intermediary between poet and larger,<br />

unknowable forces—unknowable at least for now. There is<br />

more <strong>to</strong> be unders<strong>to</strong>od; there is meaning up ahead, <strong>to</strong> be<br />

gathered and unders<strong>to</strong>od. Somewhere in the world, this poet<br />

is called, is wanted, has a purpose, a destination. This<br />

mystery prepares us for the final sentence, the poem’s most<br />

resonant and memorable phrase: “Darkly he rose, and<br />

then I slept.”<br />

And so what begins as a comical act <strong>of</strong> self-blessing—something<br />

a poet as out-<strong>of</strong>-the-mainstream as O’Hara was in his<br />

own day could certainly have used—becomes a statement <strong>of</strong><br />

a deeper sense <strong>of</strong> vocation, <strong>of</strong> connection <strong>to</strong> mystery. We all<br />

know that “true” in a title is intended <strong>to</strong> signal exactly the<br />

opposite, and yet O’Hara’s poem arrives, through the vigor<br />

<strong>of</strong> its lies, at something entirely credible. Endearingly funny,<br />

marvelously knowing in its self-regard, his poem becomes a<br />

kind <strong>of</strong> <strong>to</strong>uchs<strong>to</strong>ne for makers everywhere: both a slyly ironic<br />

blessing and an evocation <strong>of</strong> the mystery <strong>of</strong> a life <strong>of</strong> art.<br />

from A True Account <strong>of</strong> Talking<br />

<strong>to</strong> the Sun at Fire Island<br />

“…Frankly I wanted <strong>to</strong> tell you<br />

I like your poetry. I see a lot<br />

on my rounds and you’re okay. You may<br />

not be the greatest thing on earth, but<br />

you’re different. Now I’ve heard some<br />

say you’re crazy, they being excessively<br />

calm themselves <strong>to</strong> my mind and other<br />

crazy poets think that you’re a boring<br />

reactionary. Not me.<br />

Just keep on<br />

like I do and pay no attention. You’ll<br />

find that people always will complain<br />

about the atmosphere, either <strong>to</strong>o hot<br />

or <strong>to</strong>o cold <strong>to</strong>o bright or <strong>to</strong>o dark, days<br />

<strong>to</strong>o short or <strong>to</strong>o long.<br />

If you don’t appear<br />

at all one day they think you’re lazy<br />

or dead. Just keep right on, I like it.<br />

And don’t worry about your lineage<br />

poetic or natural. The Sun shines on<br />

the jungle, you know, on the tundra<br />

the sea, the ghet<strong>to</strong>. Wherever you were<br />

I knew it and saw you moving. I was waiting<br />

for you <strong>to</strong> get <strong>to</strong> work.<br />

A T R I B U T E T O F R A N K O ’ H A R A<br />

8<br />

And now that you<br />

are making your own days, so <strong>to</strong> speak,<br />

even if no one reads you but me<br />

you won’t be depressed. Not<br />

everyone can look up, even at me. It<br />

hurts their eyes.”<br />

Essay on Style<br />

—W.S. Merwin<br />

For Frank O’Hara, writing poetry was tightrope walking.<br />

What he balanced on that swaying, impossible, all-butnonexistent<br />

surface up in the vastnesses <strong>of</strong> mid-air is part <strong>of</strong><br />

what those <strong>of</strong> us who love his poetry keep recognizing, step<br />

by step, as we read his poems. All <strong>of</strong> it, apparently, is there at<br />

once: the <strong>to</strong>tally serious and the utterly go<strong>of</strong>y, high camp and<br />

startling plainness, the dailiness <strong>of</strong> existence and the<br />

perennial risk <strong>of</strong> once-only art. For all their singularity, their<br />

<strong>to</strong>ne and stance and daring, their difference from those <strong>of</strong><br />

anyone else at all, his poems <strong>of</strong>ten seem luminously transparent,<br />

and it becomes clear that for Frank O’Hara life itself was<br />

tightrope walking. Excitement and terror, the naked-new and<br />

the fondly clung-<strong>to</strong>, were balanced in each moment without<br />

particular regard for probability. And the hilarity, at every<br />

move. He is one <strong>of</strong> the funniest <strong>of</strong> poets, and his seriousness<br />

was never in danger <strong>of</strong> falling in<strong>to</strong> earnestness. “You just go<br />

on your nerve,” he says in that other great essay on style, his<br />

“Personism: A Manifes<strong>to</strong>.” But you don’t just go on that.<br />

There had <strong>to</strong> be the talent. And it had <strong>to</strong> be his own.<br />

So “Essay on Style” is scarcely an essay in any ready-made<br />

sense, but a run-through. And style is a way <strong>of</strong> moving,<br />

appearing, performing, presenting. One <strong>of</strong> its elements is the<br />

unexpected, but that in turn has subtle laws <strong>of</strong> its own. It<br />

cannot just be any old unexpected thing, there has <strong>to</strong> be an<br />

authenticity <strong>to</strong> it that is part <strong>of</strong> its surprise, becoming the<br />

as<strong>to</strong>nishing leaps and turns that we recognize as O’Hara’s<br />

“personally.” And the voice, <strong>of</strong> course, is part <strong>of</strong> that: the

phrases that seem <strong>to</strong> have been picked out <strong>of</strong> his everyday<br />

chatter and flung back with a new resonance, amplified, as<br />

though he were his own parrot:<br />

I am painting<br />

the floor yellow, Bill is painting it<br />

wouldn’t you know my mother would call<br />

up<br />

and complain?<br />

and then it’s the play-back, and himself imitating himself<br />

imitating his mother:<br />

well if Mayor Wagner won’t allow private<br />

cars on Manhattan because <strong>of</strong> the snow, I<br />

will probably never see her again<br />

and rapid though the flutter-s<strong>to</strong>p is, situations, circumstances,<br />

troubles, irritations, crises one after the other threaten <strong>to</strong><br />

enter<br />

my growingly more perpetual state<br />

and then with a reflection on the reality <strong>of</strong> an angel in the<br />

Frick we are sitting in Jack Delaney’s thinking <strong>of</strong> what Edwin<br />

is thinking about a new poem <strong>of</strong> Frank’s, and Frank begins<br />

eliminating words from the language. Not only is the wish <strong>to</strong><br />

do without words (logical connec<strong>to</strong>rs, as and but, <strong>to</strong> start<br />

with—after all, as he has said in the “Manifes<strong>to</strong>,” logic,<br />

which pain “always produces,” is “very bad for you”) is<br />

part <strong>of</strong> the style; the way he has arrived at that and the<br />

way he pursues it are also manifestations <strong>of</strong> it, and where<br />

it has got him:<br />

where do you think I’ve<br />

got <strong>to</strong>? The spectacle <strong>of</strong> a grown man<br />

decorating<br />

a Christmas tree disgusts me that’s<br />

where<br />

more words are banished from the language, and then:<br />

treating<br />

the typewriter as an intimate organ why not?<br />

By the time the poem rises <strong>to</strong> its final flounce:<br />

I am going <strong>to</strong> eat alone for the rest <strong>of</strong> my life<br />

it is clear that the style is an essay, in the old run-through<br />

sense. Trying it on and wearing it, going with it. It is his style<br />

A T R I B U T E T O F R A N K O ’ H A R A<br />

9<br />

that makes the poems complete when he ends them, and<br />

makes them work, as they do, again and again. When he<br />

talks <strong>of</strong> treating the typewriter as an intimate organ because<br />

“nothing else is (intimate)” he is describing, more or less,<br />

what he has done. The poems work because their intimacy or<br />

their play at intimacy, their closeness and their performance<br />

convey something <strong>of</strong> O’Hara, naked, postured, made, and<br />

immediately unquestionable, recognizable and pure. And<br />

after “Essay on Style” we are on <strong>to</strong> Mary Desti’s Ass, which<br />

we never do get news <strong>of</strong>.<br />

from Essay on Style<br />

[…] drinking a cognac while Edwin<br />

read my new poem it occurred <strong>to</strong> me how impossible<br />

it is <strong>to</strong> fool Edwin not that I don’t know as<br />

much as the next about obscurity in modern verse<br />

but he<br />

always knows what it’s about as well<br />

as what it is do you think we can ever<br />

strike as and but, <strong>to</strong>o, out <strong>of</strong> the language<br />

then we can attack well since it has no<br />

application whatsoever neither as a state<br />

<strong>of</strong> being or a rest for the mind no such<br />

things available<br />

where do you think I’ve<br />

got <strong>to</strong>? the spectacle <strong>of</strong> a grown man<br />

decorating<br />

a Christmas tree disgusts me that’s<br />

where<br />

that’s one <strong>of</strong> the places yetbutaswell<br />

I’m glad I went <strong>to</strong> that party for Ed Dorn<br />

last night though he didn’t show up do you think<br />

,Bill, we can get rid <strong>of</strong> though also, and also?<br />

maybe your<br />

lettrism is the only answer treating<br />

the typewriter as an intimate organ why not?<br />

nothing else is (intimate)<br />

no I am not going<br />

<strong>to</strong> have you “in“ for dinner nor am I going “out”<br />

I am going <strong>to</strong> eat alone for the rest <strong>of</strong> my life

Hôtel Transylvanie<br />

—Barbara Guest<br />

The first clue <strong>to</strong> the meaning <strong>of</strong> the poem is the title, a<br />

nineteenth-century title. Transylvania belonged once <strong>to</strong><br />

the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It belonged once <strong>to</strong> Romania.<br />

It is in the Carpathian Mountains where Dracula comes<br />

from. Although we note O’Hara does not mention this<br />

blood-thirsty Count.<br />

In our times the Carpathians have been a refuge for those<br />

fleeing the Communist regimes <strong>of</strong> Romania and Hungary.<br />

It is just possible that this hotel with the haunted name may<br />

have been noted by O’Hara on his walks in Paris, and that<br />

his imagination lent <strong>to</strong> it a sinister aspect and an accord<br />

with a rumored place <strong>of</strong> political refuge, as much as with<br />

Count Dracula.<br />

If the Hôtel Transylvanie were staged, and the poem is<br />

theatrical as are many <strong>of</strong> O’Hara’s poems, the hotel guests<br />

would wear masks. Disguise is a theme <strong>of</strong> the poem. Another<br />

is chance. Chance has a role in gambling and poetry. In a<br />

place like the Hôtel Transylvanie they may speak <strong>of</strong> political<br />

duels; there is even a mention by the poet <strong>of</strong> “rigging the<br />

deck” (<strong>of</strong> cards). These guests have escaped from a sinister<br />

regime; they may be in disguise, in order <strong>to</strong> live.<br />

it will take them a long time <strong>to</strong> know<br />

who I am/ why I came there/ what and why I am and made <strong>to</strong> happen…<br />

The residents <strong>of</strong> the Hôtel believe in chance, which may help<br />

them <strong>to</strong> survive while gambling with cards and with life.<br />

oh hôtel, you should be merely a bed<br />

surrounded by walls where two souls meet […]<br />

but not as cheaters at card have something <strong>to</strong> win….<br />

O’Hara is wishing there were not the false note, that the<br />

poem would not be forced <strong>to</strong> obey the omens, the music <strong>of</strong><br />

the poem be less forbidding. In this sort <strong>of</strong> hotel faces wear a<br />

mask. O’Hara puts on his mask as the poem gradually edges<br />

<strong>to</strong>ward the zones <strong>of</strong> danger. The poem is now about surface<br />

disequillibrium. The setting <strong>of</strong> the poem begins <strong>to</strong> wobble as<br />

the inhabitants <strong>of</strong> the hotel hide in their dominos, hissing<br />

Shall we win at love or shall we lose […]<br />

but not as cheaters at cards have something <strong>to</strong> win…<br />

A T R I B U T E T O F R A N K O ’ H A R A<br />

10<br />

their dubious origin and employment suggests a<br />

sublime moment <strong>of</strong> dishonest hope….<br />

This is a moment <strong>of</strong> melodrama, and one asks why, but the<br />

poet is leading us through his own sense <strong>of</strong> the dramatic, or<br />

melodramatic. He is aware that he will write something any<br />

minute that will both puzzle and frighten the reader. It will<br />

not be about the hotel, but about his own life. O’Hara has<br />

been readying himself for this explosion about himself, the<br />

mask he wears. He chooses now <strong>to</strong> take <strong>of</strong>f his mask and<br />

addresses himself:<br />

you will continue <strong>to</strong> sing on trying <strong>to</strong> cheer everyone up<br />

and they will know as they listen with excessive pleasure that you’re dead<br />

and they will not mind that they have let you entertain<br />

at the expense <strong>of</strong> the only thing you want in the world<br />

This is a Shelleyan moment in O’Hara’s writing, the admitted<br />

loss <strong>of</strong> poetic power. His time has been spent trying “<strong>to</strong> cheer<br />

everyone up.” It is not that this poem is one <strong>of</strong> his triumphs.<br />

In this poem he achieves what he has always attempted.<br />

<strong>Poetry</strong> has presented him with fictions and <strong>to</strong>o much reliance<br />

on his genius. He has betrayed his abilities through pleasure<br />

and power. It has eluded him until now, the icy experience <strong>of</strong><br />

the fleetingness <strong>of</strong> poetry, the possible loss, even when<br />

addressed. Of the poetic moment. Now he confronts himself<br />

in a moment <strong>of</strong> testing, and knows he has experienced the<br />

loss he writes about, the loss <strong>of</strong> poetic power, and through<br />

this moment <strong>of</strong> recognition regains it.<br />

We realize his continued addressing <strong>of</strong> the hotel is due <strong>to</strong> an<br />

identification with it in all its disguises, and the final disguise<br />

is the hotel as the personification <strong>of</strong> himself when he urges:<br />

oh hôtel […] you have only <strong>to</strong> be<br />

as you are being, as you must be, as you always are […]<br />

no matter what fate deals you or the imagination discards like a tyrant….<br />

from Hôtel Transylvanie<br />

Shall we win at love or shall we lose<br />

can it be<br />

that hurting and being hurt is a trick forcing the love<br />

we want <strong>to</strong> appear, that the hurt is a card<br />

and is it black? Is it red? Is it a paper, dry <strong>of</strong> tears<br />

chevalier, change your expression! The wind is sweeping over<br />

the gaming tables ruffling the cards/ they are black and red<br />

like a Futurist <strong>to</strong>rture and how do you know it isn’t always there<br />

waiting while doubt is the father that has you kidnapped by friends

yet you will always live in a jealous society <strong>of</strong> accident<br />

you will never know how beautiful you are or how beautiful<br />

the other is, you will continue <strong>to</strong> refuse <strong>to</strong> die for yourself<br />

you will continue <strong>to</strong> sing on trying <strong>to</strong> cheer everyone up<br />

and they will know as they listen with excessive pleasure that you’re dead<br />

and they will not mind that they have let you entertain<br />

at the expense <strong>of</strong> the only thing you want in the world/ you are amusing<br />

as a game is amusing when someone is forced <strong>to</strong> lose as in a game I must<br />

[…]<br />

The Sanity <strong>of</strong> Frank O’Hara<br />

—Thom Gunn<br />

At first I found it difficult relating “To the Harbormaster”<br />

with what I had already read by Frank O’Hara. I knew,<br />

I suppose, mainly the Lunch Poems, written in a relaxed free<br />

verse with a gentle jokey <strong>to</strong>ne, full <strong>of</strong> the trivia <strong>of</strong> his lunchhour,<br />

which is somehow never boring. He enjoys himself in<br />

those poems, and we enjoy ourselves <strong>to</strong>o, his style being<br />

immensely seductive (it’s the rhe<strong>to</strong>ric <strong>of</strong> pretending <strong>to</strong><br />

have no rhe<strong>to</strong>ric).<br />

But “To the Harbormaster” is so sad! This one does not seem<br />

improvised but is written, like late Shakespeare, in iambic lines<br />

moving irregularly between tetrameter and pentameter, which<br />

gives the poem a solemn and deliberate sound. “I am always<br />

tying up/ and then deciding <strong>to</strong> depart.” Such an undecorated<br />

statement may sound like the bemused self- deprecation <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Lunch Poems, but it has more disastrous consequences. The<br />

mastering image <strong>of</strong> the poem is <strong>of</strong> the body as boat— O’Hara<br />

is both boat and captain <strong>of</strong> the boat: “with the metallic coils <strong>of</strong><br />

the tide/ around my fathomless arms” (the arms as ship’s<br />

screws? He sounds a little like Inspec<strong>to</strong>r Gadget), “or I am hard<br />

alee with my Polish rudder/ in my hand and the sun sinking“ he<br />

is comically at a loss, with his penis useless in his hand: it is <strong>to</strong>o<br />

late, <strong>to</strong>o late for anything, he is unable <strong>to</strong> understand the forms<br />

<strong>of</strong> his vanity, and by that word he does not mean self-conceit,<br />

but the essential triviality <strong>of</strong> human affairs, vanitas vanitatem.<br />

The rhe<strong>to</strong>ric <strong>of</strong> this poetry subsumes the jokes and the slightly<br />

grotesque images in a quiet yearning despair.<br />

A T R I B U T E T O F R A N K O ’ H A R A<br />

11<br />

After the sun has started sinking, the poem is able <strong>to</strong> accommodate<br />

even the <strong>of</strong>fer <strong>of</strong> his will <strong>to</strong> the Harbormaster. But who<br />

is the Harbormaster? Before I read Brad Gooch’s book, I<br />

couldn’t make out if the poem was addressed <strong>to</strong> a lover or <strong>to</strong><br />

God. Gooch tells us it is <strong>to</strong> the painter Larry Rivers, but that<br />

still does not eliminate the presence <strong>of</strong> other possibilities: it is<br />

spoken, after all, <strong>to</strong> one who is in charge, or seems <strong>to</strong> be, the<br />

lover with whom he can find no repose, lover as god, rather<br />

like the addressee <strong>of</strong> Rochester’s poem “Absent from Thee”<br />

(his wife, perhaps, spoken in terms <strong>of</strong> a God from whom he<br />

has estranged himself through his vanity).<br />

All <strong>of</strong> which sets us up for the admirable s<strong>to</strong>icism <strong>of</strong> the<br />

ending—sturdy, brave and truthful:<br />

Yet<br />

I trust the sanity <strong>of</strong> my vessel; and<br />

if it sinks, it may well be in answer<br />

<strong>to</strong> the reasoning <strong>of</strong> the eternal voices,<br />

the waves which have kept me from reaching you.<br />

Waves are the medium for a ship as the air is the medium for<br />

a human being. They exist in an eternity different from<br />

God’s, and different again from the life-span <strong>of</strong> the ship or<br />

the man, and opposed <strong>to</strong> both, in a sense. That is the way<br />

things are, and O’Hara had better trust in the sanity <strong>of</strong> his<br />

body. “Sanity”—what a great word! It appears that both the<br />

light-hearted hedonism <strong>of</strong> other poems and the s<strong>to</strong>icism <strong>of</strong><br />

this are equally based on this common sense, this steady<br />

health <strong>of</strong> mind.<br />

To The Harbormaster<br />

I wanted <strong>to</strong> be sure <strong>to</strong> reach you;<br />

though my ship was on the way it got caught<br />

in some moorings. I am always tying up<br />

and then deciding <strong>to</strong> depart. In s<strong>to</strong>rms and<br />

at sunset, with the metallic coils <strong>of</strong> the tide<br />

around my fathomless arms, I am unable<br />

<strong>to</strong> understand the forms <strong>of</strong> my vanity<br />

or I am hard alee with my Polish rudder<br />

in my hand and the sun sinking. To<br />

you I <strong>of</strong>fer my hull and the tattered cordage<br />

<strong>of</strong> my will. The terrible channels where<br />

the wind drives me against the brown lips<br />

<strong>of</strong> the reeds are not all behind me. Yet<br />

I trust the sanity <strong>of</strong> my vessel; and<br />

if it sinks it may well be in answer<br />

<strong>to</strong> the reasoning <strong>of</strong> the eternal voices,<br />

the waves which have kept me from reaching you.<br />

—

The Transparent Man 1<br />

T H E L A S T I N G A P P E A L<br />

O F F R A N K O ’ H A R A<br />

—Brad Gooch<br />

When I was an aspiring teenage poet skulking in my<br />

bedroom in sixties suburban <strong>America</strong>—Wilkes-Barre,<br />

Pa.—there was only Bob Dylan and T. S. Eliot. Then all <strong>of</strong> a<br />

sudden there was Frank O'Hara. His admission in<strong>to</strong> the little<br />

pantheon I kept on my shelf was accomplished by The New<br />

<strong>America</strong>n <strong>Poetry</strong>, an anthology <strong>of</strong> post-war, anti-academic<br />

poets edited by Donald Allen—re-issued a few years ago with<br />

the less shiny title, The Postmoderns. Of all the poets<br />

represented—including such innova<strong>to</strong>rs as Charles Olson,<br />

Allen Ginsberg, Jack Spicer—O’Hara puzzled me the most.<br />

From that puzzlement grew fascination and eventually,<br />

full-blown, adolescent literary love.<br />

Being a teenager, I was selfish. I didn’t read anything twice<br />

that didn’t speak somehow <strong>to</strong> my cornered existence. I’d been<br />

perfectly happy <strong>to</strong> sit at the diner with Dylan and Ginsberg,<br />

ordering up frothy milkshakes <strong>of</strong> poetic prose and wolfing<br />

down hamburgers spiced with the ketchup <strong>of</strong> radical politics.<br />

But with O’Hara I felt as if I’d been invited <strong>to</strong> a more adult<br />

restaurant—French?—where the cuisine wasn’t immediately<br />

recognizable, but was invitingly complex, beautiful even. I<br />

heard a poetic voice I couldn’t quite identify, but which in<br />

retrospect was filled with ingredients I craved—Manhattan<br />

slang, delinquent liberty, French surrealism, gay romance. I<br />

would roll the line “My quietness has a man in it, he is<br />

transparent” around in my head like a smooth, clear marble.<br />

I also read in a biographical note that Kenneth Koch, a friend<br />

<strong>of</strong> O’Hara’s, taught at Columbia College, so I resolved <strong>to</strong><br />

make my way somehow in<strong>to</strong> his class, which, in 1971, I did.<br />

1 This article emerged from an interview with Rebecca Wolff, PSA’s Programs Associate.<br />

A T R I B U T E T O F R A N K O ’ H A R A<br />

12<br />

By assigning written imitations <strong>of</strong> Rimbaud, Pound, Stevens,<br />

and Williams, Koch freely spilled <strong>to</strong> us all the secret<br />

ingredients <strong>of</strong> his and O’Hara’s poetry. He talked <strong>of</strong> the<br />

grand permission O’Hara gave <strong>to</strong> include your own most<br />

trivial daily thoughts and experiences in poetry—the “I do<br />

this, I do that” aesthetic. He made a few dark comments<br />

about O’Hara’s life at which my antennae shot up. “Avoid<br />

masochistic love affairs,” he counseled us. “They interfere<br />

with your poetry.” (I’m still not so sure about that one.)<br />

Kenneth was indeed the <strong>to</strong>ggle switch between the poetry and<br />

the life. At a l<strong>of</strong>t party for Allen Ginsberg, he said <strong>to</strong> me,<br />

“Who do you want <strong>to</strong> meet?” “John Ashbery,” I answered<br />

ambitiously, and soon John and I were talking. Then one<br />

night at The Ninth Circle, an innocuous dance bar in the<br />

West Village that attracted college students, Ashbery<br />

introduced me <strong>to</strong> J.J. Mitchell, a boyfriend <strong>of</strong> O’Hara’s,<br />

who’d been with him the night <strong>of</strong> his fatal accident.<br />

The line between life and art was<br />

more dotted by him than by any<br />

poet. All information was at once<br />

gossip and aesthetic illumination.<br />

Still a student, I was soon attending parties at the poet<br />

Kenward Elmslie’s <strong>to</strong>wnhouse. These were Frank O’Hara<br />

parties—just without O’Hara, who’d been dead for five years<br />

by then. I could hear snippets <strong>of</strong> that “voice” I’d first heard<br />

on the page in “The Day Lady Died” or “Poem (Lana Turner<br />

Has Collapsed!)” emerge ventriloquially from the mouths <strong>of</strong><br />

Alex Katz, or Joan Mitchell, or Joe LeSueur, or Patsy<br />

Southgate. All I could bring <strong>to</strong> the table was the accidental<br />

distinction <strong>of</strong> being one <strong>of</strong> the first <strong>of</strong> a generation who<br />

hadn’t known O’Hara personally, yet was steeped enough in<br />

the poems <strong>to</strong> be able <strong>to</strong> identify LeSueur as the owner <strong>of</strong> the<br />

seersucker jacket <strong>of</strong> “Joe’s Jacket,” or Freilicher as the Jane<br />

<strong>of</strong> “Chez Jane.” (The revela<strong>to</strong>ry Collected Poems didn’t<br />

appear until the end <strong>of</strong> 1971.) One night at a dinner party at<br />

LeSueur’s my ears burned as dishy tales were <strong>to</strong>ld <strong>of</strong> O’Hara<br />

over cognac and joints. I remember naively thinking, “I’d like<br />

<strong>to</strong> write his biography,” never considering that I was a<br />

twenty-year-old poet who could barely string five pages <strong>of</strong><br />

prose <strong>to</strong>gether for an academic essay.

Fifteen years later my life had become more prosaic. I had a<br />

literary agent, and, soon enough, a publisher, and the kind<br />

permission <strong>of</strong> O’Hara’s sister, Maureen, <strong>to</strong> write an authorized<br />

biography. While I was sympathetic with W.H. Auden’s<br />

famous distaste for the exposure <strong>of</strong> poets’ lives, I felt that<br />

part <strong>of</strong> O’Hara’s exceptionalism was that his poetry was a<br />

teasing invitation <strong>to</strong> biography. While the footnotes—possum<br />

prints or not—<strong>to</strong> Eliot’s The Waste Land sent the reader <strong>of</strong>f<br />

in search <strong>of</strong> St. Augustine’s Confessions or the libret<strong>to</strong> <strong>of</strong><br />

Wagner’s Tristan, O’Hara’s poems provoked the reader <strong>to</strong><br />

skim black-and-white snapshots <strong>of</strong> painters and poets clustered<br />

in the Cedar Tavern. The line between life and art was<br />

more dotted by him than by any poet. All information was at<br />

once gossip and aesthetic illumination. O’Hara’s attitude on<br />

the page made all traditional distinctions between minor and<br />

major, life and art, seem hackneyed and fake—and so<br />

emboldened a sympathetic biographer.<br />

Writing a biography requires some method acting. You try <strong>to</strong><br />

imagine yourself in the head <strong>of</strong> the protagonist. (Having<br />

worked my way through O’Hara’s childhood and the “letters<br />

home” <strong>of</strong> his Navy years, I felt that I was perhaps coming at<br />

his adult years differently from many <strong>of</strong> his contemporaries,<br />

whose attitude about family and past, as Grace Hartigan<br />

explained <strong>to</strong> me, tended <strong>to</strong> be, “You leave that!”) My own<br />

social life picked up as I found myself attempting <strong>to</strong> channel<br />

O’Hara’s buoyant, friendly, chatty demeanor at parties. I was<br />

always memorizing one or another poem, running through it<br />

on the subway. The words inevitably would ricochet with the<br />

words <strong>of</strong> an O’Hara letter I was reading, or an interview, and<br />

suddenly two dots would be connected. For instance, I read<br />

how Daisy Alden discovered O’Hara crying at his own<br />

thirtieth birthday party thrown at Grace Hartigan’s studio,<br />

and saying, “Because <strong>to</strong>day I am thirty years old and have so<br />

little time left,” and I realized that this was the date he began<br />

“In Memory Of My Feelings,” a poem written over four<br />

days, which included the double-entendre, “Grace/<strong>to</strong> be born<br />

and live as variously as possible.” Whatever mental light<br />

bulbs were lit during the writing were switched on by<br />

memorizing the poems, with the help as well <strong>of</strong> O’Hara’s<br />

crammed date books.<br />

One tired literary axiom is that biographers are inevitably<br />

disillusioned by their subjects. O’Hara defied this rule as<br />

well. For when I came <strong>to</strong> the end <strong>of</strong> City Poet: The Life and<br />

Times <strong>of</strong> Frank O’Hara, I felt reassured that O’Hara had<br />

pretty much been going on his nerve, just as I’d always imagined<br />

he had, creating a life that perfectly fit the writer <strong>of</strong><br />

those intensely, achingly lyrical, yet oh so smartly urbane and<br />

A T R I B U T E T O F R A N K O ’ H A R A<br />

13<br />

modern poems. In that sense, O’Hara’s life was an inspiration.<br />

He was just a bit more complicated than even I’d<br />

imagined. But how could he have had, as Larry Rivers<br />

tabulated in his eulogy, “at least sixty people in New York<br />

who thought Frank O’Hara was their best friend,” and not<br />

be complex?<br />

Now when that line rolls through my head occasionally—<br />

“My quietness has a man in it, he is transparent”—I can’t<br />

help but continue with the nuance <strong>of</strong> the ensuing three lines,<br />

which I didn’t understand so well before writing the biography:<br />

“and he carries me quietly, like a gondola through the<br />

streets./ He has several likenesses, like stars and years, like<br />

numerals/ My quietness has a number <strong>of</strong> naked selves.”

What’s With<br />

Modern Art? 1<br />

T H E A RT R E V I E W S<br />

O F F R A N K O’HARA<br />

—Michael Price<br />

“What matters is not eternal life but eternal vivacity”<br />

—Friederich Nietzsche<br />

It seems as though lately we can’t s<strong>to</strong>p talking about<br />

.Frank O’Hara. How fortunate! For O’Hara’s genius is,<br />

as Charles Olson once advocated, <strong>to</strong> make the private act<br />

public, and that private world we see in O’Hara’s varied<br />

and spontaneous oeuvre is a public world <strong>of</strong> wonder.<br />

How does this wonder figure in<strong>to</strong> art reviews? With O’Hara,<br />

it is the push magus. The poem meets the blurb meets<br />

criticism. And what could be more earned and rewarding<br />

than words from a poet who is so very much the movement<br />

or impetus <strong>of</strong> the painter, <strong>of</strong> the gesture <strong>to</strong> make art, in his<br />

life and in his poems? So it can be said that O’Hara is not a<br />

critic. He is a poet first and also a great art mind. (Baudelaire<br />

used <strong>to</strong> say that the best criticism <strong>of</strong> a work <strong>of</strong> art would be<br />

another work <strong>of</strong> art). Craft and technique as concepts have<br />

no place in an O’Hara review. Instead, thinking <strong>of</strong> his<br />

famous quip from “Personism: A Manifes<strong>to</strong>,” O’Hara goes<br />

on his own crepuscular nerve. His art writings are checkered<br />

with <strong>of</strong>f-hand one-liners, beautiful word-play and bona-fide<br />

cognitive leaps that are genius. Take for example this from<br />

“Blanche Dombek”:<br />

They wipe from one’s mind some <strong>of</strong> their more graceful<br />

contemporaries in the way that a gust <strong>of</strong> wind obliterates a<br />

phrase <strong>of</strong> music when it is played in a stadium.<br />

1 What’s with Modern Art?, edited By Bill Berkson (Mike and Dale’s Press, 1999).<br />

A T R I B U T E T O F R A N K O ’ H A R A<br />

14<br />

One thinks <strong>of</strong> Keats’ revela<strong>to</strong>ry maxim “Beauty is truth,<br />

truth beauty” in this excerpt from “Salvador Dali”:<br />

...the artist himself, nude, conducts you in<strong>to</strong> a beautiful candy-dream<br />

where your faithful dog is asleep at your feet and the sea purrs at<br />

your fingertips. There are sweet vapors and the rich revela<strong>to</strong>ry grain<br />

<strong>of</strong> woods and the vastly impressive passivity <strong>of</strong> megalomania, but it<br />

is not exactly a revolutionary’s dream. He calls forth the minor or<br />

repressed admirations, sexual, tactile sybaritic, technical—the subject<br />

is no longer <strong>of</strong> paranoiac importance—and makes a monument.<br />

The tradition <strong>of</strong> poet as art critic<br />

has rich company in the twentieth<br />

century: Stein, Yeats, Stevens,<br />

Pound, Moore and Auden <strong>to</strong> name a<br />

few. O’Hara takes an important<br />

place in this lineage...<br />

There is, as well, much <strong>of</strong> O’Hara’s “I do this, I do that”<br />

sensibility in the art writings. His charm lies in his ease at<br />

jumping from information (him telling you something you<br />

can use) <strong>to</strong> prescience (his leaps in<strong>to</strong> the unknown). Perhaps<br />

the place this is most evident is in his comments titled David<br />

Smith: Sculpting Master <strong>of</strong> Bol<strong>to</strong>n Landing, which ran on<br />

WNDT-TV (November 18, 1964):<br />

It is the nature <strong>of</strong> sculpture <strong>to</strong> be there. If you don’t like it you wish<br />

it would get out <strong>of</strong> the way, because it occupies space which your<br />

body could occupy. Smith’s sculptures are, big or small, figurative or<br />

abstract, very complete, very attentive <strong>to</strong> your presence, full <strong>of</strong><br />

interest in and for you. As an example, they have no boring views:<br />

circle them as you may, they are never napping. They present a <strong>to</strong>tal<br />

attention and they are telling you that that is the way <strong>to</strong> be. On<br />

guard. In a sense they are benign, because they <strong>of</strong>fer themselves for<br />

your pleasure. But beneath that kindness is a warning: don’t be<br />

bored, don’t be lazy, don’t be trivial and be proud. The slightest loss<br />

<strong>of</strong> attention leads <strong>to</strong> death. The primary passion in these sculptures is

<strong>to</strong> avert catastrophe, or <strong>to</strong> sink beneath it in a major way. So, as with<br />

the Greeks, it is a tragic art.<br />

O’Hara would famously make poems in the midst <strong>of</strong> a party.<br />

He could also convey deep insight on visual arts on cue,<br />

seemingly <strong>to</strong> anyone interested. His Q & A exposé in<br />

Ingenue (December, 1964) with a group <strong>of</strong> high-school<br />

students is at once a lesson on humor, particularity,<br />

compassion, wit, and beauty. Take this exchange as example:<br />

Q: Is it in poor taste <strong>to</strong> admire and like an artist who is still<br />

alive and near <strong>to</strong> the art world, especially if what he paints<br />

appeals <strong>to</strong> teen-agers in style and color? Jane Cee Salmy,<br />

Morris<strong>to</strong>wn High School, New Jersey<br />

A: It is never in poor taste <strong>to</strong> admire anyone, except possibly<br />

someone like Hitler. It is especially important <strong>to</strong> admire an<br />

artist while he is alive, so that he may have some pleasure<br />

and comfort as a result <strong>of</strong> his efforts. If what he paints<br />

appeals <strong>to</strong> teenagers, it should hardly be held against him<br />

since teens are the future and an integral part <strong>of</strong> his<br />

audience.<br />

The tradition <strong>of</strong> poet as art critic has rich company in the<br />

twentieth century: Stein, Yeats, Stevens, Pound, Moore and<br />

Auden <strong>to</strong> name a few. O’Hara takes an important place in<br />

© John Jonas Gruen<br />

A T R I B U T E T O F R A N K O ’ H A R A<br />

15<br />

this lineage, especially given that the shift <strong>of</strong> consciousness<br />

that emerged within the Abstract Expressionist phenomena in<br />

New York could be seen, from a Western his<strong>to</strong>rical<br />

perspective, as the most substantial shift in the movement <strong>of</strong><br />

visual art since cave etchings. And with our own dearth <strong>of</strong><br />

synergy (I speak for myself and you) between the two genres<br />

<strong>to</strong>day (on the West Coast there isn’t a poet and a painter<br />

living within 400 miles <strong>of</strong> each other), O’Hara’s example<br />

becomes particularly poignant. His is a his<strong>to</strong>rical model, and<br />

my generation would do well <strong>to</strong> take heed and study it, say,<br />

like au<strong>to</strong> mechanics or method acting.<br />

Of course, one could just leave <strong>of</strong>f with any analysis <strong>of</strong> his<br />

prowess as a critic and simply enjoy the particular wit and<br />

confidence in the reviews that typify an O’Hara poem. One<br />

could just read the book. Or one could call up Bill Berkson<br />

for a quick tu<strong>to</strong>rial or the inside s<strong>to</strong>ry, as his knowledge <strong>of</strong><br />

O’Hara’s life and writings is second <strong>to</strong> none. I’ve had the<br />

luck <strong>of</strong> doing both.<br />

Back row, left <strong>to</strong> right: Lisa de Kooning; film direc<strong>to</strong>r Frank Perry and his wife, script writer Eleanor Perry; John Myers; Anne Porter; Fairfield Porter;<br />

interior designer Angelo Torricini; pianist Arthur Gold; Jane Wilson; Kenward Elmslie; painter Paul Brach; Jerry Porter (behind Brach, Nancy Ward;<br />

Katharine Porter). Second row, left <strong>to</strong> right: Joe Hazan; Clarice Rivers; Kenneth Koch; Larry Rivers. Seated on couch: Miriam Shapiro (Brach); pianist<br />

Robert Fizdale; Jane Freilicher; Joan Ward; John Kacere; Sylvia Maizell. Kneeling on the right, back <strong>to</strong> front: Alvin Novak; Bill de Kooning; Jim Tommaney. Front<br />

row: Stephen Rivers; Bill Berkson; Frank O’Hara; Herbert Machiz. Water Mill, Long Island, 1961.