South African Deeds Journal

South African Deeds Journal - Department of Rural Development ...

South African Deeds Journal - Department of Rural Development ...

- No tags were found...

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

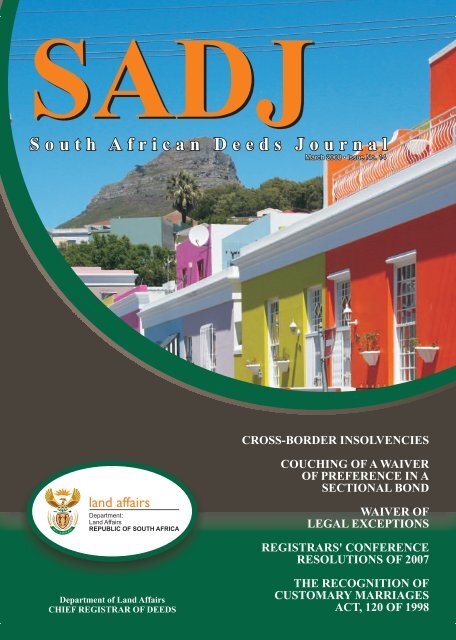

<strong>South</strong> <strong>African</strong> <strong>Deeds</strong> <strong>Journal</strong><br />

March 2008 • Issue No. 14<br />

CROSS-BORDER INSOLVENCIES<br />

land affairs<br />

Department:<br />

Land Affairs<br />

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA<br />

Department of Land Affairs<br />

CHIEF REGISTRAR OF DEEDS<br />

COUCHING OF A WAIVER<br />

OF PREFERENCE IN A<br />

SECTIONAL BOND<br />

WAIVER OF<br />

LEGAL EXCEPTIONS<br />

REGISTRARS' CONFERENCE<br />

RESOLUTIONS OF 2007<br />

THE RECOGNITION OF<br />

CUSTOMARY MARRIAGES<br />

ACT, 120 OF 1998

GUIDELINES FOR ARTICLES<br />

IN THE SADJ<br />

SADJ welcomes contributions, in any of the 11 official languages,<br />

especially from deeds office staff and practitioners. The following<br />

guidelines should be complied with:<br />

1. Contributions should as far as possible be original and not published elsewhere.<br />

2. Contributions should be useful or of interest to the conveyancing practice and land<br />

issues. The decision of the editorial committee is final.<br />

3. Authors are required to provide their involvement or interest in any matter discussed<br />

in their contributions.<br />

4. Footnotes should be avoided. Case reference, for instance, should be incorporated into<br />

the text.<br />

5. When referring to publications, the publisher, city and date of publication should be<br />

provided. When citing reported or unreported cases and legislation, full reference details<br />

should be included.<br />

6. Articles should be in a format compatible with Micro-soft Word and should either be<br />

submitted by e-mail or, together with a printout, on a stiffy or compact disk. Letters to the<br />

editor, however, may be submitted in any format.<br />

7. The editorial committee and the editor reserve the right to edit contributions as to style<br />

and language and for clarity and space.<br />

8. Acceptance of material for publication is not a guarantee that it will be included in a<br />

particular issue, since this must depend on the space available.<br />

9. Articles should be submitted to Allen West at e-mail: ASWest@dla.gov.za or Private Bag<br />

X659, Pretoria 0001.<br />

land affairs<br />

Department:<br />

Land Affairs<br />

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA<br />

i

land affairs<br />

Department:<br />

Land Affairs<br />

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA

C<br />

ontents<br />

E<br />

ditorial<br />

News<br />

Discussion on section 35A of the Income Tax Act 25<br />

Cross-Border Insolvency Law 30<br />

Property Law Update<br />

Couching of Waiver of Preference in a Sectional Bond 3<br />

Massing and Adiation vis à vis Massing and Election 5<br />

Registrars' Conference Resolutions of 2007 8<br />

The Recognition of Customary Marriages Act, 120 of 1998 9<br />

Beneficiary's Disposal in a Trust and Transfer Duty Implications 17<br />

Sales from Estates: Section 18(3) Act 66 of 1965 19<br />

Chief Masters Directive 3 of 2006: Appointment of Executors<br />

and/or Master's Representatives in Deceased Estates by the Master 20<br />

Waiver of Legal Exceptions 25<br />

Change of Names of Building Societies and Banks<br />

of Immovable Property in <strong>South</strong> Africa<br />

Does Agricultural Land Still Exist given the Stalwo v Wary case?<br />

27<br />

32<br />

Case Law<br />

Books<br />

Conveyancing Through the Cases 34<br />

Articles Published in Legal <strong>Journal</strong>s 34<br />

Letters to the Editor<br />

Testamentary Conditions and Redistribution Agreements – Reply 1 35<br />

Section 4(1)(b) – A rethink 35<br />

Lapsing of Real Rights of Extension 36<br />

SADJ – October 2006 – Transfer Duty : Acquisition of Immovable 36<br />

Property by a Company, Close Corporation or Trust:<br />

Article by PS Franck<br />

Other features<br />

The <strong>Deeds</strong> Registry as a Necessary Economic Infrastructure 2<br />

Long Distance Runner 7<br />

Reflecting the Past 40 Years 14<br />

<strong>Deeds</strong> Training Spreads its Wings 16<br />

DISCLAIMER<br />

The views expressed in the articles published in this journal do not bind the<br />

Department of Land Affairs and the Chief Registrar of <strong>Deeds</strong>. The Chief<br />

Registrar of <strong>Deeds</strong> does not necessarily agree with the views of the<br />

contributors.<br />

HOW TO SUBSCRIBE<br />

Anybody who would like to be placed on the mailing list for the SADJ, must<br />

submit their postal address to SCMohlake@dla.gov.za<br />

PRINTER<br />

Lesedi Litho Printers<br />

88 Visagie Street, PRETORIA<br />

Editorial Committee<br />

Allen West (Editor) - <strong>Deeds</strong> Training<br />

Joanne Dusterhoft - King William's Town<br />

Tebogo Monnanyana - Bloemfontein<br />

Ali van der Ross - Vryburg<br />

Hennie Geldenhuys - Office of the Chief Registrar of <strong>Deeds</strong><br />

Lood Vosloo (Sub-Editor) - Cape Town<br />

Zandré Lombaard (Scribe) - <strong>Deeds</strong> Training (Scribe)<br />

Dorethea Samaai - Directorate: Communication Services<br />

Marie Grovè<br />

- <strong>Deeds</strong> Training<br />

Elizabeth Govender - Pietermaritzburg<br />

Alan Stephen<br />

- Johannesburg<br />

Levina Smit<br />

- Kimberley<br />

George Tsotetsi<br />

- Office of the Chief Registrar of <strong>Deeds</strong><br />

Gustav Radloff<br />

- Conveyancer, MacRobert Inc.<br />

André Schoeman - Office of the Surveyor General, Pretoria<br />

The new year has literally commenced<br />

with a bang, albeit with or without load<br />

shedding. This issue is once again<br />

bumper-packed with interesting<br />

articles and news.<br />

Photos are provided on courses and conferences for readers to try<br />

and identify previous Registrars and <strong>Deeds</strong> Office officials.<br />

The 2007 resolutions taken by the Registrars are included. Please<br />

note that they have become operative with effect from 2 January<br />

2008.<br />

The article chosen as the best article in the previous issue was the<br />

one by the former Registrar of <strong>Deeds</strong> Kimberley, Mr Willie<br />

Swanepoel on Fideicommissums. Accolades were received from<br />

far and wide for the article on Robben Island together with the<br />

superb photography. Thanks once again Loodt on a wellresearched<br />

article.<br />

Abelated blessed new year to all.<br />

ALLEN WEST - EDITOR<br />

Contributions may be sent to the Editor:<br />

Via e-mail or post<br />

ASWest@dla.gov.za<br />

AS West<br />

Private Bag X659<br />

PRETORIA<br />

0001<br />

This journal is also published on the Department of Land Affairs'<br />

website:<br />

www.dla.pwv.gov.za<br />

CONTRIBUTORS:<br />

A S West • A Boraine • L J Vosloo • R Rossouw • A van Wyk • M M<br />

Meyer • L Kilbourne • I Broodryk • M Grovè • T Maree<br />

COVER PHOTO<br />

Allen West - Editor<br />

Our Front Cover picture this month shows a colourful row of<br />

historic houses on the slopes of Signal Hill in the Cape Town city<br />

bowl, which is known as the “Malay Quarter”, so named after the<br />

inhabitants who have lived there since they were freed from<br />

slavery in the early 1800s. The area is a major tourist attraction,<br />

hence the colourful outside paint schemes of some of the houses.<br />

It is hardly imaginable that in the 1930s, due to the deterioration of<br />

many of these historic buildings, it was considered demolishing<br />

the houses to make way for development. A very informative<br />

paper, written by Cape Town professor Fabio Todescini and<br />

published on the website http://www.international.icomos.<br />

org.victoriafalls2003/papers/A2-6%20-%20 Todescini.pdf gives<br />

an authoritative insight in the background of the Malay Quarter, or<br />

Bo Kaap and its inhabitants, who have shaped this unique<br />

heritage site.<br />

1

The <strong>Deeds</strong> Registry as a Necessary<br />

Economic Infrastructure<br />

By: Professor Andreas van Wyk<br />

University of Stellenbosch<br />

Astrike of <strong>Deeds</strong> Registry officials during 2006 hardly received<br />

attention in the highest quarters of Government. The reaction<br />

might well have been that it is a strike by just another relatively<br />

obscure group of aggrieved civil servants, within the<br />

Department of LandAffairs.<br />

In reality, the offices of the registrars of deeds, which are<br />

mostly situated in areas where there are also Divisions of the<br />

High Court, form a vital piece of economic infrastructure.<br />

Without it our modern free market system would hardly<br />

function or function with great difficulty, as has been shown in<br />

countries aligned to the former Soviet Union. Likewise, in<br />

many Third World Countries, the lack of a proper land register<br />

stifles economic development.<br />

As an everlasting asset, land forms the most obvious security<br />

one has to offer for the repayment of a loan. However, this<br />

presupposes that the particular piece of land may be clearly<br />

identifiable. Only then will individual or institutionalized money<br />

lenders be prepared to provide credit on the strength of a real<br />

right against the debtor's land this which we nowadays call a<br />

mortgage bond.<br />

This is the basis upon which the whole modern banking<br />

system is built. If all land in a country belongs to the State, then<br />

banks are largely restricted to providing loans to the different<br />

organs of State or merely providing short term loans, even if<br />

individual property rights on land are acknowledged without a<br />

credible system which proves X or Y's legal right. So for<br />

example, in Indonesia, or in other parts of the developing world<br />

no bank will provide significant credit to say a Javanese<br />

subsistence farmer.<br />

It is exactly in this area where <strong>South</strong> Africa inherited one of its<br />

most significant strategic advantages from the Roman Dutch<br />

law. Fundamental to a credible cadastre (property register) is<br />

the survey performed by many generations of surveyors,<br />

which enables almost each piece of land to be identified. This<br />

provides not only the creation of a register of who owns a piece<br />

of land or has rights thereto, but may also provide this<br />

information for public knowledge.<br />

This all may sound obvious, but it is not really so?<br />

In some of the most highly developed Western countries, such<br />

as Britain there is not really an equivalent to <strong>South</strong> Africa's<br />

reliable deeds registers (property registers).<br />

During the late Roman times the transfer of land took place by<br />

physically handing over a document in which the transferor<br />

(i.e. the seller of a house) confirmed that he transfers the land<br />

to the transferee (the buyer). This event was not accompanied<br />

by public notification. This in essence is still the situation in<br />

England today with their “conveyance by deed” and<br />

complicated matters to outsiders who wish to know who the<br />

owner of a specific piece of land is.<br />

However, in other parts of North Western Europe things<br />

developed differently during the Middle ages. The transfer of<br />

land had to take place in public, usually in the presence of<br />

family or neighbours. This developed into a practice where this<br />

function was performed in the presence of the local judicial<br />

official who had to keep a copy of the transfer deed in his office.<br />

This finally gave rise to legislation enacted between 1529 and<br />

1580 by the then Austrian-Spanish rulers who also ruled the<br />

Lower Lands of Holland. Accordingly, all transfers of land and<br />

rights thereto (such as a mortgage or servitude) had to be<br />

registered in the local court.<br />

This is precisely what happened in the Cape. Simultaneously<br />

with the establishment of a separate Council of Justice (“Raad<br />

van Justisie”) in 1680, all land transfers were registered there<br />

th<br />

until the early 19 century when the British administration in<br />

the Cape established a separate registration office for land<br />

titles. The Roman-Dutch principles upon which this office then<br />

functioned remained, and indeed still does so to this day.<br />

<strong>South</strong> <strong>African</strong> <strong>Deeds</strong> Registries are therefore government<br />

offices where information relating to land and certain other<br />

related judicial information (such as antenuptial contracts) are<br />

readily provided for public access. Information kept there<br />

enable potential land purchasers or credit providers to decide<br />

whether they wish to proceed with such transactions or not.<br />

Land registers may function in one or the other way. In certain<br />

Western European countries a so-called positive registration<br />

system is employed, which means that information recorded<br />

may be fully relied upon. By implication this means that the<br />

relevant State will guarantee the accuracy of the information<br />

contained in its land registers.<br />

In <strong>South</strong> Africa, and elsewhere, the system however is<br />

negative. This means that the information contained in deeds<br />

registers create a strong presumption, but total reliability<br />

cannot be guaranteed.<br />

Nevertheless, great care is taken to ensure the accuracy of our<br />

registers. In its present form, the <strong>Deeds</strong> Registries Act, 47 of<br />

1937 places a great deal of responsibility on conveyancers<br />

(the specialized attorneys who deal with land transfers and the<br />

rights thereto) to take responsibility for this.<br />

On the other hand, our system also relies to a great extent on<br />

2

the professionalism of deeds examiners employed by the<br />

State to ensure the integrity of the registers.<br />

Of course our land registration system and all that it is built<br />

upon only forms part of the total judicial infrastructure on which<br />

our economy is based. If anarchy in a given area escalates to<br />

such an extent that a bank can no longer retrieve its<br />

outstanding debt on a property by way of public auction, then<br />

the best land registration system becomes meaningless.<br />

However, one must not underestimate the value to the<br />

economy of a reliable land register.<br />

The above article originally appeared in the SAKE24 supplement of DIE<br />

BURGER and is reproduced here with kind permission from Media24, and the<br />

author. See also the monetary value of bond and bond registrations published in the<br />

October 2007-issue of the SADJ on pages 15 to 20 which is ancillary to the<br />

essence of this article. It was translated from the original Afrikaans by L J Vosloo. -<br />

Editor<br />

Couching of Waiver waiver of preference Preference<br />

in a Sectional sectional bond Bond<br />

By: Marie Grové<br />

<strong>Deeds</strong> Training, PRETORIA<br />

The Sectional Titles Act, 95 of 1986 does not provide for the waiver of a personal servitude in a sectional bond. The matter was<br />

recently discussed at the Registrars' Conference, and the Registrars resolved that the bond must be made subject to the usufruct and<br />

the waiver must be contained in the bond, and not the annexure:<br />

“52/2007 Couching of waiver of preference of usufruct<br />

Uncertainty at present prevails as to how the waiver or preference of a real right, such as a usufruct, must be couched in<br />

a sectional bond.<br />

Resolution:<br />

The usufructuary must either personally or in terms of an agent appear before the conveyancer. The bond must be<br />

made subject to the usufruct and the waiver must be contained in the bond and not the annexure.”<br />

Unfortunately the conference did not state whether the Power of Attorney (PA) must be lodged when the usufructuary (or holder of the<br />

personal servitude) appoints an agent by means of a PA. It can be reasoned both ways whether the PAmust be lodged or not.<br />

In the first instance, the PA falls within the ambit of the documents described in Annexure 6B, as referred to in regulation 40 of the<br />

Sectional Title regulations, in which case the PAshould not be lodged.<br />

It can also be reasoned that the personal right is waived in terms of the <strong>Deeds</strong> Registries Act, 47 of 1937, and not in terms of the<br />

Sectional TitlesAct, 95 of 1986. Therefore the PAmust be lodged.<br />

It is suggested that the waiver of preference in the bond, as directed by the Conference should be set in the example below, namely:<br />

“ Mortgagor hereby binds as a FIRST MORTGAGE, subject to the conditions set out in the annexure to this bond:<br />

A unit consisting of:<br />

(a) Section No 2 as shown and more fully described on Sectional Plan No SS 91/1996 in the scheme known as BATCAVES in<br />

respect of the land and building or buildings situated at ERF 957 ELDORAIGNE TOWNSHIP, in the local authority of City<br />

of Tshwane Metropolitan Municipality of which section the floor area, according to the said sectional plan is 90<br />

(NINETY) square metres in extent; and<br />

(b)<br />

an undivided share in the common property in the scheme apportioned to the said section in accordance with the<br />

participation quota as endorsed on the said sectional plan.<br />

Held by virtue of Deed of Transfer ST<br />

SUBJECT TO ALL THE TERMS AND CONDITIONS CONTAINED THEREIN AND A LIFELONG USUFRUCT IN FAVOUR OF<br />

23

EMMA GEEL, IDENTITY NUMBER 520101 0032 00 2, UNMARRIED, WHICH RIGHT IS BEING WAIVED IN FAVOUR OF<br />

THIS BOND, AS WILLAPPEAR LATER ON IN THE BOND<br />

*I, the undersigned, ALEXANDER HONEY, duly authorized by virtue of a power of attorney, signed at Pretoria on 7 January<br />

2004, by EMMA GEEL, IDENTITY NUMBER 520101 0032 002, UNMARRIED, the holder of the usufruct over the within<br />

mentioned property, do hereby waive the usufruct on behalf of the usufructuary, in favour of the mortgagee.<br />

Signed at Pretoria on 20 July 2004<br />

____________________________________<br />

Alexander Honey<br />

Duly authorized by Usufructuary<br />

SIGNED at PRETORIA on 26 July 2004<br />

____________________________________<br />

Mortgagor / Duly authorized agent of<br />

Mortgagor<br />

Before me<br />

Elaine Buckeroo<br />

Suite 16, Wildberry Park<br />

777 Wildberry Avenue<br />

MUCKLENEUK<br />

__________________________<br />

CONVEYANCER<br />

Registered at PRETORIA on<br />

__________________________<br />

REGISTRAR OF DEEDS<br />

*The exact wording of the waiver is the prerogative of the preparer.<br />

See page 5 for other resolutions taken by Conference. - Editor<br />

4

Massing and Adiation<br />

Massing and Election<br />

vis à vis<br />

By: Allen West<br />

<strong>Deeds</strong> Training, PRETORIA<br />

This article is not intended to provide legal treatise on massed<br />

estates, but merely to provide a simple distinction between<br />

massing and adiation, and massing and election.<br />

The question begging an answer is whether a will must provide<br />

a limited interest in the massed property in favour of the<br />

surviving spouse. According to Wille's Mortgage and Pledge<br />

(Third Edition) on page 299 it is a prerequisite that the<br />

surviving spouse receives a limited interest in the massed<br />

property. The authority for this is probably based on the<br />

provisions of section 37 of theAdministration of EstatesAct, 66<br />

of 1965. Furthermore the case of Secretary, <strong>South</strong> <strong>African</strong><br />

Association v Mostert; 1873 Buch 31 provides that “ the<br />

supervisor has accepted some benefit under the will”. Adiation<br />

is thus dependent on the surviving spouse obtaining a limited<br />

interest in the massed estate.<br />

However, when election occurs in a massed estate entirely,<br />

there is no necessity for a limited interest and the quid pro quo<br />

may lie distinct from the inheritance.<br />

Thus to summarize, where there is a massed estate, and the<br />

surviving spouse has abided by the terms of the joint will,<br />

adiation will be necessary where a limited interest is received,<br />

and election necessary where no limited interest is obtained.<br />

From a conveyancing perspective the provisions of section 21<br />

and regulation 50(2)(b) of the <strong>Deeds</strong> Registries Act 47 of 1937<br />

requires closer perusal.<br />

In the case of massing and adiation, where a joint estate is<br />

involved, the surviving spouse does not have to join the<br />

executor in the passing of transfer of the massed property,<br />

provided proof is submitted that the surviving spouse has<br />

adiated.<br />

However, where massing and election has occurred, and the<br />

property forms an asset in the joint estate, the surviving<br />

spouse must join the executor in the passing of the transfer of<br />

the massed property and documentary evidence in the form of<br />

an affidavit from the surviving spouse must be lodged to prove<br />

the election of the surviving spouse.<br />

Although the latter proof<br />

is not a specific requirement in terms of the Act, section 4(1)(a)<br />

sanctions the request for same.<br />

In both instances; where the property forms an asset in a joint<br />

estate, the joint estate must be divested (see regulation<br />

50(2)(c)).<br />

Resolutions taken at the Conference<br />

of Registrars 2007<br />

By: Allen West<br />

<strong>Deeds</strong> Training, PRETORIA<br />

The Registrars held their annual conference during November<br />

2007 and 52 resolutions were taken. These resolutions have<br />

become operative from 2 January 2008 and are applicable to<br />

all <strong>Deeds</strong> Registries.<br />

What follows is merely those conference resolutions deemed<br />

necessary to draw examiners and practitioners attention to<br />

and which has an effect on the day to day practice of<br />

conveyancing.<br />

RCR 3/2007 - Proof of Intestacy<br />

Given the fact that a death notice cannot be accepted as proof<br />

of children born out of wedlock, it should also not be accepted<br />

as proof that a person died leaving no valid will. Does<br />

conference concur and if so, what proof should be required?<br />

Resolution:<br />

A death notice cannot serve as evidence of intestacy. Proof, in<br />

the form of an affidavit from the executor/representative, must<br />

be insisted upon. However, in the case of a transfer by<br />

endorsement in terms of section 45 of Act No. 47 of 1937, a<br />

regulation 49(1)(g) certificate from the Master will be<br />

acceptable.<br />

RCR 4/2007 - Sectional Title Mortgage Bonds<br />

Where a sectional title unit is subject to conditions, imposed in<br />

favour of the Home Owners Association, restricting transfer,<br />

etc. must the bond registered over such unit be made specially<br />

subject to such conditions, in the light of RCR 5 of 1987, read<br />

with RCR 22 of 2005?<br />

Resolution:<br />

Yes, sectional bonds must be made subject to restrictive<br />

home-owners association conditions. RCR 13/2002 is hereby<br />

confirmed.<br />

RCR 6/2007 - Registration of Usufruct over right to extend<br />

Can a usufruct be registered over a right to extend as provided<br />

for in terms of section 25(9) ofAct No. 95 of 1986?According to<br />

RCR 41/2003 and RCR 37/1996, and Act No. 95 of 1986 it is<br />

possible to register a usufruct over an exclusive use area (this<br />

amplifies the registration of a “right over a right” which the law<br />

does not allow).Also, see RCR 44/2003.<br />

Resolution:<br />

No, Act No. 95 of 1986 does not provide for a usufruct to be<br />

registered over a right of extension.<br />

5

RCR 7/2007 - Regulation 68(11)<br />

An authorized person/agent cannot make an oath on behalf of<br />

his/her principal (see RCR 6.12/1999). What is the position<br />

with an affidavit in terms of regulation 68(11) Act No. 47 of<br />

1937, where the agent (conveyancer) acts in terms of a<br />

general power of attorney on behalf of the Mortgagee (The<br />

Bank)?<br />

Resolution:<br />

RCR 6.12/1999 must also be applied to applications and<br />

affidavits in terms of regulation 68(11) of Act No. 47 of 1937. A<br />

general power of attorney mandating an agent to make an<br />

affidavit on behalf of his/her principal is contra bonis mores<br />

and should not be allowed.<br />

RCR 12/2007 - Conditions in Antenuptial Agreements<br />

RCR 34/2006 states: the following clause is inserted in an<br />

Antenuptial Contract: “The accrual system is to apply without<br />

modification to their intended marriage, provided that should<br />

either party be an unrehabilitated insolvent at the time of the<br />

dissolution of the intended marriage then the said accrual<br />

system shall not apply”.<br />

Is the proviso legal and enforceable?<br />

Resolution:<br />

Such a proviso is not legal and to the disadvantage of future<br />

creditors. The Matrimonial PropertyAct only allows that certain<br />

assets can be excluded from the accrual system. See Vorster<br />

v Steyn 1981 (2) SA831 (O).<br />

In view of the comments made by the judge in ex parte<br />

Wismer 1950 (2) 195 CPD the above resolution should be<br />

revisited.<br />

Resolution:<br />

Registrars of <strong>Deeds</strong> must register the contract. Should any<br />

dispute arise as to the contents thereof, the parties concerned<br />

may refer the matter to court for clarification. See ex parte<br />

Wismer 1950 2 195 CPD on pages 198 and 199. (RCR<br />

34/2006 is hereby withdrawn).<br />

RCR 15/2007 - Application of Section 68(1)<br />

Where a personal servitude has lapsed and the land<br />

encumbered thereby is transferred, is it peremptory to request<br />

an application in terms of section 68(1), or will the<br />

documentary proof lodged as a supporting document suffice?<br />

Resolution:<br />

Section 68(1) must be complied with in all instances where a<br />

personal servitude lapses for any reason.<br />

RCR 20/2007 - VA copy already lodged<br />

Where application and affidavit is made for the issue of a<br />

certified copy of a title deed, bond, etc. for which a VA copy has<br />

already been issued, must the application be made in terms of<br />

regulation 68(7), or will an application in terms of regulation<br />

68(1) be acceptable?<br />

Resolution:<br />

The application must be made in terms of regulation 68(1) and<br />

not 68(7). RCR 26.1/1996 is hereby confirmed in respect of the<br />

disclosure of the full facts.<br />

RCR 34/2007 - CROSS-BORDER INSOLVENCY<br />

A Foreign Court has issued a judgment to liquidate a company<br />

that owns property in <strong>South</strong> Africa. A foreign trustee now<br />

requests the registrar of deeds to note a liquidation order<br />

against the company. Does the registrar of deeds have the<br />

power to note such an order to enable a foreign trustee to deal<br />

with company's assets?<br />

Resolution:<br />

The registrar of deeds must decline to note such an order,<br />

unless it has been recognized by a <strong>South</strong> <strong>African</strong> Court. See<br />

Deutsche Bank AG v Moser and Another 1999 (4) SA 216<br />

(C).<br />

RCR 42/2007 - Lapsing of Right of Extension<br />

Is it the duty of the registrar of deeds to check the right of<br />

extension on transfer of a unit to determine if same has lapsed,<br />

and if so, how must the 15B(3)-certificate be couched or must<br />

section 68(1) be complied with, where same has lapsed?<br />

Resolution:<br />

No, it is not the duty of the registrar of deeds to check the right<br />

of extension on transfer of a unit. It is the duty of the<br />

conveyancer to determine whether or not the right of extension<br />

has lapsed. If it has been determined that such right has<br />

lapsed, then a section 68(1) application by the body corporate<br />

must be lodged. The 15B(3) certificate must reflect that a right<br />

of extension has been registered, but that such right has<br />

lapsed.<br />

RCR 43/2007 - Non-disclosure of Period of Extension<br />

What procedure must be followed where it is ascertained<br />

subsequent to registration that the reservation of a right of<br />

extension does not disclose a period of time in which the right<br />

must be exercised?<br />

Resolution:<br />

A Notarial variation agreement entered into between the body<br />

corporate and the developer, with the written consent of all<br />

members of the body corporate as well as with the written<br />

consent of the mortgagee of each unit in the scheme, failing<br />

the agreement or the obtaining of all consents, an order of<br />

court must be obtained.<br />

Should a body corporate not be in existence, a section 4(1)(b)<br />

application may be lodged where a right has been reserved,<br />

from time to time, but no specific period has been stipulated in<br />

the condition.<br />

RCR 48/2007 - Subdivision of Agricultural Land Act 70 of<br />

1970<br />

Where a sectional title register is opened on land<br />

encompassing the word “farm” in the property description<br />

must CRC 6 of 2002 be applied in that the consent of the<br />

Minister must be obtained, alternatively proof that such land is<br />

not deemed to be agricultural land?<br />

6

Resolution:<br />

Yes, CRC 6 of 2002 is applicable.<br />

RCR 49/2007 - Opening of Sectional Title register and Act<br />

21 of 1940<br />

Where a sectional title register is opened on land within 95<br />

metres from a main or building restriction road, must the<br />

provisions of section 11(4) of Act No. 21 of 1940 be applied as<br />

per the uniform practice applicable to conventional transfers of<br />

land to two or more persons?<br />

Resolution:<br />

Yes, section 11(4) ofAct No. 21 of 1940 must be adhered to.<br />

Uncertainty at present prevails as to how the waiver of<br />

preference of a real right, such as a usufruct, must be couched<br />

in a sectional bond.<br />

Resolution:<br />

The usufructuary must either personally or in terms of an agent<br />

appear before the conveyancer. The bond must be made<br />

subject to the usufruct and the waiver must be contained in the<br />

bond and not the annexure.<br />

Readers are advised to obtain a full set of the resolutions from<br />

their law society or from the <strong>Deeds</strong> Registry.<br />

*See also the article by Marie Grovè on page 3 of this issue - Editor<br />

*RCR 52/2007 - Couching of Waiver of Preference in<br />

Sectional<br />

Long<br />

Mortgage Bond<br />

Distance<br />

Runner<br />

Susan Hurter is an Assistant Registrar of <strong>Deeds</strong> at the Pretoria <strong>Deeds</strong> Registry. She is a regular participant in long distance<br />

running events. In 2007 she participated in five 100-miler ultra marathons. She won all her 100-miler marathons and in the<br />

Washie 100 miler she came 9th overall.<br />

Those of us who wonder why Susan does this - It is because she can!<br />

7

CONFERENCE OF REGISTRARS 2007<br />

Back Row: K. Pillay, J . Badenhorst, Alla n Stephen, S. Mbatha, G. Tsotsetsi, I. Singo, P. M e sefo, A . van der Ross<br />

Front Row: L. du Pont, H. Geldenhuys, L. Smit, A. West, N. Matanga, Z. Rahmann, C. Knoessen, A. Lombaard,<br />

A. Reynolds, A. Sepp<br />

8

The Recognition of Customary<br />

Marriages Act, 120 of 1998<br />

By: Margaret Meyer<br />

Masters’ Training PRETORIA<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

The Recognition of Customary Marriages Act, 120 of 1998,<br />

came into operation on 15 November 2000, and gives full legal<br />

recognition to customary marriages for the first time in the<br />

history of <strong>South</strong>Africa.<br />

Prior to the commencement of the Act, customary marriages,<br />

(better known as customary unions) did not enjoy the same<br />

status as civil marriages concluded in terms of the Marriage<br />

Act, 25 of 1961. Customary unions received partial recognition<br />

for purposes of certain legislation and common law, if they<br />

were registered under the Black Administration Act 38 of 1927.<br />

Partners in customary unions were treated as spouses for the<br />

1 2<br />

purpose of workmen's compension, income tax, and<br />

3<br />

maintenance.<br />

Customary unions, as codified in the Black Administration Act,<br />

were also institutions in which women suffered unequal status<br />

and rights, to men. The Black Administration Act treated all<br />

women, regardless of age, capacity and marital status as<br />

4<br />

minors. Women were not allowed to own property, sue or be<br />

sued in court, or exercise the power of contract. Women could<br />

not negotiate or terminate their marriages, nor could they have<br />

legal custody of their children.<br />

The unequal status of customary marriages reflected the<br />

general approach of the pre-democratic governments to<br />

customary law in <strong>South</strong> Africa. It was viewed as a system of<br />

law that was 'inferior' to common law and legislation. Its<br />

acceptance as 'law' was based on a concept of 'repugnancy'<br />

defined by Western, Colonial and Christian values. For<br />

example, customary unions were not fully recognized<br />

because, 'potentially polygamous', they were 'against good<br />

5<br />

morals'<br />

THE LEGAL RECOGNITION OF CUSTOMARY<br />

MARRIAGES<br />

Which marriages are recognized?<br />

According to section 1 of the Act 'customary marriage' is<br />

defined as a marriage concluded in accordance with<br />

customary law, while 'customary law' is defined as the<br />

customs and usages traditionally observed among the<br />

indigenous <strong>African</strong> peoples of <strong>South</strong> Africa and which form<br />

part of the culture of those peoples.<br />

From the above definitions it is clear that customary marriages<br />

concluded in terms of Hindu and Muslim rites are not affected<br />

by the Act, and remain invalid unless they were solemnized in<br />

terms of the MarriageAct, 25 of 1961 or the Civil UnionsAct, 17<br />

of 2006.<br />

Customary marriages entered into before 15 November<br />

2000<br />

Section 2(1) of the Act recognizes customary marriages<br />

entered into before the commencement of the Act (15<br />

November 2000), provided that such marriages were validly<br />

concluded in terms of customary law and existed at the<br />

commencement of theAct.<br />

According to section 2(3) if a person was a spouse in more<br />

than one validly concluded customary marriage as at date of<br />

the commencement of the Act, all the marriages are<br />

recognized as marriages. Polygamous marriages are thus<br />

given legal recognition.<br />

Customary marriages entered into after 15 November<br />

2000<br />

Section 2(2) recognizes customary marriages entered into<br />

after the commencement of the Act (15 November 2000),<br />

provided the marriage complies with the requirements of the<br />

Act. This also includes polygamous marriages entered in<br />

terms of theAct [section 2(4)].<br />

The general requirements for a valid customary marriage<br />

entered into after the commencement of the Act are as<br />

6<br />

follows:<br />

• The prospective spouses must both be above the age of<br />

18 years;<br />

• They must both consent to be married to each other<br />

under customary law.<br />

• The marriage must be negotiated and entered into or<br />

celebrated in accordance with customary law.<br />

• If either of the prospective spouses is a minor, both his or<br />

her parents, or if he or she has no parents, his or her legal<br />

guardian, must consent to the marriage. If there is no<br />

7<br />

legal guardian, theAct provides for substitute consent.<br />

• The parties must not be prohibited from marriage<br />

because of relationship by blood or affinity as determined<br />

by customary law.<br />

• In addition to the above requirements, a husband in a<br />

customary marriage who wishes to enter into a further<br />

customary marriage with another woman after the<br />

commencement of the Act, must comply with a further<br />

requirement set out in section 7(6) of the Act, namely an<br />

application to the Court to approve a written contract<br />

which will regulate the future matrimonial property system<br />

of his marriages.<br />

Subsequent civil marriages<br />

A man and a woman between whom a customary marriage<br />

subsists may marry each other in terms of the Marriage Act, 25<br />

9

of 1961, if neither of them is a spouse in a subsisting customary<br />

8<br />

marriage with any other person.<br />

A spouse in a customary marriage may, however, not marry<br />

another person in terms of civil law during the subsistence of<br />

9<br />

such customary marriage.<br />

REGISTRATION OF CUSTOMARY MARRIAGES<br />

Duty to register<br />

Registration provides certainty, and consequently section 4 of<br />

the Act provides that all customary marriages must be<br />

registered.<br />

Customary marriages entered into before the commencement<br />

of the Act, which are not already registered in terms of any<br />

other law, had to be registered within a period of 12 months<br />

after the commencement of the Act, or within such a period as<br />

the Minister may from time to time prescribe by notice in the<br />

10<br />

Gazette.<br />

Marriages entered into after the commencement of the Act<br />

must be registered within a period of three months after the<br />

conclusion of the marriage or within such period as the Minister<br />

may from time to time prescribe by notice in the Gazette.<br />

Although registration of a customary marriage is peremptory in<br />

terms of the Act, section 4(9) provides that failure to register a<br />

customary marriage, does not affect the validity of that<br />

marriage.<br />

Proof of existence of a customary marriage that has not been<br />

registered can pose a problem to the Master when an estate is<br />

reported and it is suggested that the Master is justified in<br />

insisting on proof of registration of the marriage for estate<br />

purposes.<br />

Section 4(8) provides that “a certificate of registration of a<br />

customary marriage issued under this section or any other law<br />

providing for the registration of customary marriages<br />

constitutes prima facie proof of the existence of the customary<br />

marriage and of the particulars contained in the certificate.”<br />

Who may apply to register a marriage?<br />

Section 4(2) specifically allows 'either spouse' to register a<br />

marriage on behalf of both spouses. This provision read with<br />

section 4(5)(b) makes it possible for a surviving spouse in a<br />

customary marriage, whose marriage is not registered at the<br />

time of death of the other spouse, to register the marriage after<br />

the death of the other spouse in order to satisfy the Master's<br />

requirement of proof of registration.<br />

During the process of developing the law, the women's rights<br />

lobby argued strongly for a provision that would allow wives to<br />

register marriages without their husbands. The purpose was to<br />

ensure that spouses who are reluctant to register their<br />

marriage do not frustrate the other spouse or the purpose of<br />

the Act. Because a customary marriage is a process that<br />

occurs over time and may involve more than a ceremony, it is<br />

easy to challenge its existence. Women, in particular, have the<br />

most to lose if the customary marriage is not registered. Men<br />

have been able to challenge customary marriages in order to<br />

avoid maintaining former spouses or the wives dependent on<br />

the estates they have inherited as male heirs.<br />

Essentially, the Act accepts that it is not always in the interests<br />

11<br />

of both spouses to register their marriage.<br />

The Act also allows 'interested parties to apply to register a<br />

12<br />

customary marriage on behalf of the spouses.<br />

An interested party may be a friend, a relative, a traditional<br />

leader or one of the people who participated in the marriage<br />

negotiations between the two families. He or she could also be<br />

one of the husband's other wives or the children of the<br />

marriage or of the husband from another marriage. Also<br />

relevant may be persons with an interest in communal land<br />

under the control of the husband, business partners and fellow<br />

trustees. It appears to be left within the discretion of the<br />

registering officer as to who constitutes an interested party. As<br />

long as the party seeking to register the marriage satisfies the<br />

registering office that he or she has 'a sufficient interest in the<br />

13<br />

matter', they may apply.<br />

Requirements to register a customary marriage<br />

Section 4(2) of the Act provides that the applicants must<br />

furnish the registering officer with the prescribed information<br />

and any additional information which the registering officer<br />

may require in order to satisfy himself or herself as to the<br />

existence of the marriage.<br />

The Minister of Justice, in consultation with the Minister of<br />

Home Affairs, is responsible for creating the registration form<br />

and for identifying the necessary information the spouse or<br />

couple must provide to the registering officer.<br />

According to information obtained from the Pretoria Regional<br />

Office of the Department of Home Affairs the following<br />

information is required to register a customary marriage after<br />

one of the spouses is deceased:<br />

• The family lobolo agreement, which contains the date of<br />

the marriage, the lobolo amount and any of the agreed<br />

information, duly signed by all the parties concerned.<br />

• If the agreement and the marriage was concluded in the<br />

rural area, the written confirmation from the Tribal Chief<br />

or King from that area to the effect that the marriage took<br />

place in that area.<br />

• The death certificate, or a certified copy thereof, in<br />

respect of the deceased spouse whose spouse is<br />

reported.<br />

• One representative each of the bride and the groom's<br />

family must accompany the surviving spouse to the<br />

nearest office of the Department of Home Affairs. All the<br />

parties must produce their identity documents during the<br />

registration process.<br />

10

• A fee of R10,00 is payable in respect of the application for<br />

registration of the customary marriage.<br />

STATUS AND CAPACITY OF SPOUSES<br />

In terms of section 6 of the Act, a wife in a customary marriage<br />

is placed on an equal footing with that of her husband as far as<br />

her status and capacity is concerned, subject, however, to the<br />

matrimonial property system governing the marriage. This<br />

means that she may now acquire assets and dispose of them,<br />

enter into contracts and litigate, on a basis of equality with her<br />

husband, in addition to any rights and powers that she might<br />

have at customary law.<br />

PROPRIETARY CONSEQUENCES OF CUSTOMARY<br />

MARRIAGES<br />

The consequences of a customary marriage differ according to<br />

whether the marriage was entered into before or after the<br />

commencement of the Act. For marriages entered into before<br />

the commencement of the Act, the proprietary consequences<br />

continue to be governed by customary law, unless an<br />

application is made to change the property regime in terms of<br />

section 10 of theAct.<br />

For marriages entered into after the commencement of the Act<br />

the proprietary consequences will depend on whether the<br />

marriage is monogamous or polygamous.<br />

Customary marriages in existence before the<br />

commencement of the Act<br />

Section 7(1) provides that the proprietary consequences of a<br />

customary marriage entered into before the commencement<br />

of the Act will continue to be governed by customary law. The<br />

question, however, is which customary law?<br />

The concepts of “in community or out of community of<br />

property” are unknown in customary law.<br />

For purposes of the administration of estates, the Master will<br />

regard customary marriages entered into before the<br />

commencement of the Act as being out of community of<br />

property.<br />

The Act allows spouses married under customary law prior to<br />

the Act to apply to a court to change their marital property<br />

regime. Section 7(4) requires the application for change to be<br />

made by both the husband and the wife. The court will grant the<br />

application if:<br />

(a) there are 'sound' reasons for the change;<br />

(b) written notice is given to all creditors owed amounts of over<br />

R500,00;<br />

(c) no one will be prejudiced by the change.<br />

If the husband has other spouses in a polygamous marriage,<br />

then they must be joined in the proceedings to ensure that their<br />

14<br />

rights are protected. Other parties who have interests in the<br />

marital property must also be joined, including the dependants<br />

of the husband and anyone else who will be affected by the<br />

change.<br />

Customary marriages entered into after the<br />

commencement of the Act<br />

Monogamous customary marriages<br />

In terms of section 7(2) of the Act the marriage property<br />

arrangement of a monogamous customary marriage is that of<br />

a marriage in community of property and of profit and loss.<br />

Monogamous customary marriages concluded after the<br />

commencement of the Act thus have the same consequences<br />

as a civil marriage.<br />

The spouses to a monogamous customary marriage can<br />

marry out of community of property, provided they enter into an<br />

antenuptial contract.<br />

Where the marriage is in community of property, it must be<br />

noted that the provisions of Chapter III and sections 18, 19, 20<br />

and 24 of Chapter IV of the Matrimonial Property Act, 88 of<br />

1984, apply to the customary marriage.<br />

Polygamous customary marriages<br />

A husband in a customary marriage who wishes to enter into a<br />

further customary marriage with another woman after the<br />

commencement of the Act, must comply with the requirement<br />

of section 7(6) of the Act, in addition to the general<br />

requirements set out in section 3 of the Act. He must make an<br />

application to court to approve a written contract which will<br />

regulate the future matrimonial property system of his existing<br />

marriage and the prospective one.<br />

In view of the fact that the Act now provides for polygamous<br />

marriages in respect of indigenous <strong>African</strong> people of <strong>South</strong><br />

Africa, the Master should take cognizance of this fact and<br />

ensure that the rights of all the spouses (where there is more<br />

than one marriage) is protected in the course of the<br />

administration of the estate.<br />

The Master will call for the written contract which regulates the<br />

deceased's marriages, duly approved by the court, if the death<br />

notice indicates the following:<br />

• the deceased was married under customary law;<br />

• the marriage is polygamous;<br />

• the second or subsequent marriage was concluded after<br />

the commencement of theAct (15 November 2000).<br />

DISSOLUTION OF CUSTOMARY MARRIAGES<br />

In terms of section 8(1) of the Act a customary marriage may<br />

only be dissolved by a court by a decree of divorce, on the<br />

ground of the irretrievable breakdown of the marriage.<br />

As with all other estates administered by the Master, a copy of<br />

the divorce order and any settlement between the parties,<br />

which has been made an order of court, must be called for in<br />

appropriate circumstances, e.g. to establish whether the<br />

deceased estate is liable for future maintenance.<br />

11

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN CIVIL AND CUSTOMARY<br />

MARRIAGES AND THEIR IMPACT ON ESTATES<br />

The practice of combining customary with civil ceremonies is<br />

common in <strong>South</strong> Africa, and many variations are possible.<br />

The spouses may celebrate a customary marriage and, on the<br />

same day, or a short while later, have it solemnized again in a<br />

civil registry office. The rites may also be reversed, when a civil<br />

marriage is followed by a traditional wedding. Dual marriages<br />

by the same spouses entered into prior to the Recognition of<br />

Customary Marriages Act, 120 of 1998 created few legal<br />

problems, because the customary union was not recognized<br />

15<br />

and the civil marriage was simply allowed to prevail.<br />

Where, however, a spouse (normally the husband) purported<br />

to marry a third person by different rights, the situation is more<br />

complicated. A migrant worker, for instance, might marry one<br />

wife in the country according to customary law, and another in<br />

the city according to civil rites. The husband, thinking in terms<br />

of his customary right to take many wives, might have been<br />

unaware of the legal implications of his actions, or a more<br />

calculating man, however might have deliberately kept his<br />

wives in the dark.<br />

Because the Recognition of Customary Marriages Act is not<br />

retrospective in effect, marriages contracted prior to the Act<br />

are still governed by rules that applied before it came into force<br />

on 15 November 2000. These rules can be divided into four (4)<br />

categories.<br />

Subsequent civil marriage by the spouse of a subsisting<br />

customary union to a third person: Situation before 2<br />

December 198 - Areas outside the Transkei<br />

Only civil marriages were deemed proper marriages, and<br />

consequently where a husband in a subsisting customary<br />

union were to marry a third person or one of his existing<br />

polygamous wives by civil rites, the civil marriage<br />

automatically superseded and extinguished the prior<br />

customary union(s). These consequences caused great<br />

16<br />

hardship for the 'discarded' customary wife and children.<br />

Section 22(7) of the Black Administration Act, 38 of 1927,<br />

however, provided some measure of protection to the<br />

discarded family when the husband died. For purposes of<br />

succession, the status of the widow and children of the civil<br />

marriage were deemed to be equivalent of their customary-law<br />

counterparts. By implication, the preferential status given the<br />

civil-law wife and children was lost and they ranked equally<br />

with the prior discarded wife (or wives) and their children.<br />

If the Master's Office or Service Point is confronted with a<br />

17<br />

situation as set out above after the Bhe decision , it should be<br />

noted that both the discarded wife and the civil-law wife will be<br />

deemed spouses of the deceased for purposes of intestate<br />

succession.<br />

Subsequent civil marriage by the spouse of a subsisting<br />

customary union to a third person: Situation after 2<br />

December 1988 until 15 November 2000<br />

Areas outside the Transkei<br />

In 1988 the Marriage and Matrimonial Property Law<br />

Amendment Act 3 of 1988, which came into operation on 2<br />

December 1988 provided that, although partners to a<br />

customary union could marry one another again by civil rites,<br />

a spouse could not validly marry a third person by civil rites<br />

during the subsistence of the customary union. Should a<br />

spouse in a customary union purport to enter into a civil<br />

marriage without first dissolving the customary union, the civil<br />

marriage will be invalid. This was confirmed in Thembisile<br />

18<br />

and Another v Thembisile and Another.<br />

When confronted with a situation as set out above, the Master<br />

or Service Point would have to determine which of the<br />

marriages (customary or civil) was invalid at the date of death<br />

of the deceased. If the deceased entered into a customary<br />

union (first Marriage) with wife A and then into a civil marriage<br />

with wife B, without first dissolving the customary union, then<br />

the civil marriage is invalid and the customary union is the only<br />

valid marriage. If the customary marriage was dissolved<br />

before the civil marriage, then the civil marriage will be the<br />

only valid marriage.<br />

Dual marriages in Transkei<br />

The 1978 Transkei Marriage Act, 21 of 1978 allowed the<br />

husband of a subsisting civil marriage to contract additional<br />

customary marriages, provided that the civil marriage was out<br />

of community of property. Likewise, a husband in a customary<br />

union, could also during the subsistence of such customary<br />

union validly contract a civil marriage with a third person,<br />

provided the civil marriage was out of community of property.<br />

Thus, when the Master or Service Point is confronted with<br />

dual marriages concluded in terms of the Transkei Marriage<br />

Act, both the civil and customary law spouses would be<br />

19<br />

deemed spouses for purposes of intestate succession.<br />

The position after 15 November 2000<br />

The Recognition of Customary Marriages Act, 120 of 1998<br />

came into operation on 15 November 2000 and revoked<br />

section 22(1) to (5) of the Black Administration Act, and the<br />

provision in the Transkei Marriage Act that permitted dual<br />

marriages.<br />

Section 2(1) of the Recognition of Customary Marriages Act<br />

determines that a marriage which is a valid marriage at<br />

customary law and existing at the commencement of the Act,<br />

is for all purposes recognized as a valid marriage.<br />

Section 10(1) provides that a man and a woman between<br />

whom a customary marriage subsists are competent to<br />

contract a civil marriage with each other if neither of them is a<br />

spouse in a subsisting customary marriage with any other<br />

person.<br />

Section 10(4) provides that despite subsection (1), no spouse<br />

of a civil marriage is, during the subsistence of such marriage,<br />

12

competent to enter into any other marriage, albeit civil or<br />

customary.<br />

The Act thus confirms that spouses married by customary<br />

union may not enter into a civil marriage if either of them is a<br />

spouse in a subsisting customary marriage with any other<br />

person. The same holds for spouses married under civil rites.<br />

They may not enter into a customary union.<br />

Editor's Note:<br />

The Department of Home Affairs who is responsible for the<br />

registration of customary marriages has ceased to register<br />

marriages subsequent to the dates referred to in section 4 and<br />

thus the matter has to be referred to court for verification of the<br />

marriage should the marriage not have been registered<br />

timeously. This is causing undue hardship for the parties who<br />

have entered into customary marriages.<br />

Foot Notes:<br />

1<br />

Compensation for Occupational Injuries and DiseasesAct<br />

130 of 1993, s 1.<br />

7<br />

8<br />

9<br />

10<br />

11<br />

12<br />

13<br />

14<br />

15<br />

Refer to sections 3(b), 4(a) & 4(c).<br />

Section 10(1).<br />

Section 3(2).<br />

The Minister of Home Affairs extended the period to<br />

November 2002, but despite the expiry period, Home<br />

Affairs has permitted registration to continue.<br />

Justice College, Customary Marriages Bench Book,<br />

February 2004, par. 4.5.<br />

Section 5(a).<br />

Justice College, Customary Marriages Bench Book,<br />

February 2004, par. 4.5.<br />

Section 7(4)(b).<br />

Benett Customary Law in <strong>South</strong> Africa (2004) 236.<br />

2<br />

The Income TaxAct 58 of 1962, s 1.<br />

16<br />

Nkambula v Linda 1951 (1) SA377 (A).<br />

3<br />

4<br />

MaintenanceAct 23 of 1962, s 1.<br />

The BlackAdministrationAct, 38 of 1927, s 11(3)(b).<br />

17<br />

Bhe and Others v Magistrate Khayelitsha and Others,<br />

2005 (1) SA580 (CC) handed down on 15 October 2004.<br />

5<br />

6<br />

Justice College, Customary Marriages Bench Book,<br />

February 2004, par. 2.1.<br />

Section 3.<br />

18<br />

19<br />

2002 (2) SA209 (T).<br />

In Khambule v The Master and Others 2007 (3) SA 403<br />

(E) it was held that the failure of parties to register the<br />

customary marriage in terms of the Transkei Marriage<br />

Act does not affect the validity thereof.<br />

Exemption Of Transfer Duty: Section 9(1)(i)<br />

Of The Transfer Duty Act 40 Of 1949<br />

By Marie Grové<br />

<strong>Deeds</strong> Training Pretoria<br />

Section 9(1)(i) of Act 40 of 1949 reads as follows:<br />

Section 9(1): “No duty shall be payable in respect of the<br />

acquisition of property by - ……. (i) the surviving or divorced<br />

spouse who acquires the sole ownership in the whole or any<br />

portion of property registered in the name of his or her<br />

deceased or divorced spouse where that property or portion is<br />

transferred to that surviving or divorced spouse as a result of<br />

the death of his or her spouse or dissolution of their marriage or<br />

union” (my underlining).<br />

The Act specifically requires that the surviving or divorced<br />

spouse should acquire “sole ownership” in the “whole” or “any<br />

portion” of a property, registered in the name of his or her<br />

spouse. The word “any portion” is used and not “any share”,<br />

which indicates that when reference is made to “portion” it will<br />

be a “defined” portion and not a “share” in the property.<br />

By way of an example, should a deceased/divorced spouse<br />

be the registered owner of an undivided share in the property,<br />

i.e. co-owner together with a third party (not his/her spouse),<br />

and the surviving/divorced spouse, who is entitled to the<br />

property, receives transfer of the share of the other spouse,<br />

the transaction will not be exempt from transfer duty in terms<br />

of section 9(1)(i). The spouse does not receive transfer of the<br />

“whole” or a ”portion” of the property and does not acquire<br />

“sole ownership”, but merely an undivided share. Strictly<br />

interpreted transfer duty should be payable in respect of such<br />

transactions.<br />

Is this an oversight by the legislator?<br />

your views please! - Editor<br />

13

Reflecting the Past 40 Years<br />

DEEDS REGISTRATION COURSE LEVEL VI 2001<br />

From Left to Right:<br />

st<br />

1 Row: MP Moya, CCE Knoesen (Lecturer),<br />

AS West (Lecturer), JF Scheepers<br />

(Director: Training), JE Grobler (Lecturer),<br />

HF Gerryts (Lecturer), A Lombaard<br />

(Lecturer).<br />

nd<br />

2 Row: HR Nkambule, VM Tango, D Hoko,<br />

MM Mokale, RT Mamabolo<br />

rd<br />

3 Row: NS Lefafa, I de Jongh, NV Makete,<br />

WL Motlhabane, PJH Gwangwa, GA<br />

Botha<br />

th<br />

4 Row: Avan Rooyen, H Nauschutz,<br />

L Coetzer, S Mallick, M van Niekerk<br />

TRANSVAAL TOWNSHIPS BOARD - 1983<br />

From Left to Right:<br />

Front: Messrs. LW Pentz (Vice-chairperson); JI Le Roux Van Niekerk (Chairperson); PF Bekker (Secretary)<br />

Behind: Messrs. H J de Beer (Registrar of Mining Titles); NC O'Shaughnessy (Representative of Surveyor General)<br />

CW Erasmus (Representative of Roads); GE Verster (Representative of Community Development);<br />

MPAuret (Representative of Local Government); WG James (Representative of Roads);<br />

JJGB Knoetze (Member); DJL Kamfer (Member); WF Olivier (Registrar of Rand Townships);<br />

DG Raath (Assistant Head of Planning) and EP de Beer (Representative of the Prime Minister's Office<br />

Section Physical Planning) Insert: Mr. DP Wilcocks (Member); Mr.APL Kotze (Member) (Pretoria).<br />

14

COURSE FOR SECTIONAL TITLES ACT - 1973<br />

From Left to Right:<br />

st<br />

1 Row: SA Walters; DJA Visser; Mrs. E Grobler; JLE Smit (Chief Registrar of <strong>Deeds</strong>); Miss. M van Ronge;<br />

MS Kruger (Course Leader); HR Gibbs<br />

nd<br />

2 Row: L Kriel; CJ Wolfaardt; CA Pienaar; BD Davidson; RN Weaving; JH Chamberlain; WFHC Swanepoel<br />

rd<br />

3 Row: DLW Westpfahl; NT Duvenage; C Streak; CH Myburgh; W Obbes (Assistant Registrar Windhoek); AN Wilson<br />

th<br />

4 Row: PJ van Rensburg; P Lategan; CL Wabeke; RR Kretzmann; L Heunis<br />

TRANSVAAL TOWNSHIPS BOARD - 1966<br />

From Left to Right:<br />

Front: Mr. H Preiss, member; Mr. ATW de Klerk, member; Mr. CP Joubert (Registrar of Mining Titles), member; Mr. LJ Vosloo<br />

(Registrar of <strong>Deeds</strong>); member; Mr. RBJ Gouws (Representative of the Department of Local Management), member;<br />

Mr. JI Le Roux Van Niekerk, (Chairperson); Mr. H Matthee, secretary; Mr. LW Pentz (Surveyor General), member; Mr.<br />

JSM Guldenpfennig, member.<br />

Behind: Mr. SG Cronje (Representative of the Department of Roads), member; Mr. DG Raath, Plannner of the Townships<br />

Board; Mr. DG Cruse, member; Mr. PPC van der Hoven, Planner of the Townships Board<br />

15

<strong>Deeds</strong> Training Spreads its Wings<br />

By: L J Vosloo<br />

<strong>Deeds</strong> Registry, CAPE TOWN<br />

The Sub-Directorate: <strong>Deeds</strong> Training periodically conducts topic courses for <strong>Deeds</strong> Office officials to keep their<br />

knowledge of the myriad of legislation, procedures and practices ship shape.<br />

Often these courses are presented at the various locations of the <strong>Deeds</strong> Offices by the lecturers from <strong>Deeds</strong> Training.<br />

The photographs were taken at one such course and show <strong>Deeds</strong> Training lecturer Wiseman Bhuqa explaining the<br />

intricacies of Customary Marriages to <strong>Deeds</strong> Office examiners from the Cape Town deeds registry.<br />

Class attendants<br />

Wiseman Bhuqua presenting lectures.<br />

16

Beneficiary's Disposal in a Trust and<br />

Transfer Duty Implications<br />

By: Roelie Rossouw<br />

Conveyancer Rossouws Attorneys, BLOEMFONTEIN<br />

RELEVANT PROVISIONS OF THE TRANSFER DUTYACT<br />

The following provisions of the Transfer Duty Act 40 of 1949<br />

(“Transfer DutyAct”) are relevant:<br />

The following definitions contained in section 1 of the Transfer<br />

DutyAct:<br />

'property' means land in the Republic and any fixtures<br />

thereon, and includes -<br />

(a) any real right in land but excluding any right under a<br />

mortgage bond or a lease or property other than a lease<br />

referred to in paragraph (b) or (c);<br />

(b) ……..<br />

(c) ……..<br />

(d) a share or member's interest in a residential property<br />

company; or<br />

(e) a share or member's interest in a company which is a<br />

holding company (as defined in the Companies Act,<br />

1973 (Act 61 of 1973) or as defined in the Close<br />

Corporations Act, 1984 (Act 69 of 1984), as the case<br />

may be), if that company and all of its subsidiary<br />

companies (as defined in the Companies Act, 1973, or<br />

Close Corporations Act, 1984), would be a residential<br />

property company if all such companies were regarded<br />

as a single entity;<br />

(f) a contingent right to any residential property or share or<br />

member's interest, contemplated in paragraph (d) or (e),<br />

held by a discretionary trust (other than a special trust<br />

as defined in section 1 of the Income Tax Act, 1962 (Act<br />

58 of 1962)), the acquisition of which is -<br />

(i) a consequence of or attendant upon the conclusion of any<br />

agreement for consideration with regard to property held<br />

by that trust;<br />

(ii) accompanied by the substitution or variation of that trust's<br />

loan creditors, or by the substitution or addition of any<br />

mortgage bond or mortgaged bond creditor; or<br />

(iii) accompanied by the change of any trustee of that trust;<br />

'residential property' means any dwelling house, holiday<br />

home, apartment or similar abode, improved or<br />

unimproved land zoned for residential use in the republic<br />

(including any real right thereto), other than -<br />

(a) an apartment complex, hotel, guesthouse or similar<br />

structure consisting of five or more units held by a person<br />

which has been used for renting to five or more persons,<br />

who are not connected persons, as defined in the Income<br />

Tax Act, 1962 (Act 58 of 1962), in relation to that person; or<br />

(b) any 'fixed property' of a 'vendor' forming part of an<br />

'enterprise” all as defined in section 1 of the Value-Added<br />

Tax Act, 1991 (Act 89 of 1991);<br />

(a)<br />

(b)<br />

(c)<br />

'transaction' means -<br />

…..<br />

…..<br />

in relation to a discretionary trust, the substitution or<br />

addition of one or more beneficiaries with a contingent<br />

right to any property of that trust, which constitutes<br />

residential property or shares or member's interest<br />

contemplated in paragraph (d) or (e) of the definition of<br />

property' or a contingent right contemplated in paragraph<br />

(f) of that definition;<br />

‘ trust' means any trust consisting of cash or other assets which<br />

are administered and controlled by a person acting in a<br />

fiduciary capacity, where such person is appointed under<br />

a deed of trust or by agreement or under the will of a<br />

deceased person.<br />

Section 2 which deals with the imposition of transfer duty in<br />

the following manner:<br />

(1) Subject to the provisions of section 9, there shall be levied<br />

for the benefit of the National Revenue Fund a transfer<br />

duty (hereinafter referred to as the duty on the value of<br />

any property …. acquired by any person on or after the<br />

date of commencement of this Act by way of a transaction<br />

or in any other manner…<br />

RELEVANT PROVISIONS OF THE TRUST PROPERTY<br />

CONTROL ACT 57 OF 1988<br />

The following definitions contained in section 1 of the Trust<br />

Property ControlAct are relevant:<br />

'trust' means the arrangement through which the ownership in<br />

property of one person is by virtue of a trust instrument made<br />

over or bequeathed -<br />

(a)<br />

(b)<br />

to another person, the trustee, in whole or in part, to be<br />

administered or disposed of according to the provisions<br />

of the trustee instrument for the benefit of the person or<br />

class of persons designated in the trust instrument or for<br />

the achievement of the object stated in the trust<br />

instrument; or<br />

to the beneficiaries designated in the trust instrument,<br />

which property is placed under the control of another<br />

person, the trustee, to be administered or disposed of<br />

according to the provisions of the trust instrument for the<br />

benefit of the person or class of persons designated in the<br />

trust instrument or for the achievement of the object<br />

stated in the trust instrument, but does not include the<br />

case where the property of another is to be administered<br />

by any person as executor, tutor or curator in terms of the<br />

provisions of the Administration of Estates Act, 1965 (Act<br />

66 of 1965);<br />

CATEGORIES OF TRUSTS<br />

It is clear from the definitions of 'property' and 'transaction'<br />

contained in the Transfer Duty Act that (for the purpose of<br />

determining whether the disposal of a beneficiary's interest in<br />

a trust will attract transfer duty) it is imperative that one should<br />

be able to differentiate between a “discretionary trust” and a<br />

trust which is not a discretionary trust for purposes of the act.<br />

The Transfer Duty Act uses the term “discretionary trust”<br />

without defining it. (For the purpose of this memorandum I will<br />

accept that the “discretionary trust” to which the act refers is<br />

the one defined by PA Olivier 'Trustreg en Praktyk' on p 114 as<br />

one where the trustees have a discretion as to which of the<br />

beneficiaries will eventually receive the income and/or capital<br />

of the trust. The rights of the beneficiaries are therefore<br />

contingent and not vested).<br />

17

The Trust Property Control Act also does not differentiate<br />

between a “discretionary trust” and a trust which is not a<br />

discretionary trust. (It does, however, differentiate in its<br />

definition of “trust” between:<br />

a trust where ownership of the trust assets vest in the trustees<br />

in paragraph - (a) of the definition and;<br />

a trust where ownership of the trust assets vest in the<br />

beneficiary/ies - in paragraph (b) of the definition.<br />

Cameron, de Waal and Wunsh Honoré's <strong>South</strong><strong>African</strong> Law of<br />

Trusts' (Fifth Edition) p 9 refers to 3.3.1 as a<br />

'ownership trust' and to 3.3.2 as a 'bewind trust'.<br />

P A Olivier 'Trustreg en Praktyk' p 111 refers to 3.3.1 as a<br />

“privaat trust” and says the following of that category of trust:<br />

“Dié soort trust is eintlik die werklike uitvloeisel van die trust in<br />

regstegniese sin met die trustee as eienaar van die trustgoed<br />

en met bepaalde of bepaalbare begunstigdes.”<br />

On p 114<br />

Olivier defines a 'discretionary trust as follows: “'n<br />

Diskressionêre trust is 'n privaat trust met die besondere<br />

kenmerk dat die begunstigdes wat uiteindelik deur die<br />

inkomste en/of kapitaal van die trust bevoordeel gaan word<br />

volgens die diskresie van òf die trustees òf 'n begunstigde<br />

bepaal moet word. Dis … 'n besondere verskynsel van die<br />

privaat trust.” It would thus appear as if Olivier acknowledges<br />

that one does find another form of the “privaat trust” where<br />

ownership of the trust assets still vest in the trustees even if<br />

they do not have a discretion as to which of the beneficiaries<br />

will eventually receive the income and/or capital.<br />

P A Olivier 'Trustreg en Praktyk' p 114 says the following<br />

regarding the practical use of a 'bewind trust': “Omdat die<br />

bewindtrust wel erkenning geniet, is dit bruikbaar in die vorm<br />

van 'n beleggingstrust wat ook 'n vorm van 'n besigheidstrust<br />

is. 'n Voorbeeld hiervan kan gevind word waar die lede van<br />

byvoorbeeld 'n prokureursfirma hulle eie gebou oprig. Dit<br />

geskied in die naam van die Omega Trust. Die vennote of hulle<br />

familietrusts is die begunstigdes en die kapitaal en inkomste<br />

en verliese van d i e O m e g a Tr u s t v e s t i g i n d i e<br />

begunstigdes.” I am of the opinion that Oliver's “Omega<br />

Trust” would only be a 'bewind trust' if the office building is<br />

registered in the name of the beneficiaries. If, as is much more<br />

common, the office building is registered in the name of the<br />

trustees the trust is an 'ownership trust' notwithstanding the<br />

fact that the beneficiaries have a vested right as regards the<br />

income and capital of the trust when either income and capital<br />

is distributed by the trustees. I base my opinion on the fact that<br />

the trustees, before they decided to distribute the capital of the<br />

trust, may (if they are entitled to do so in terms of the provisions<br />

of the trust deed) decide to sell the office building and buy<br />

another in the place thereof. The beneficiaries clearly never<br />

had a real right in either of the office buildings whilst the<br />

buildings are registered in the name of the trustees. Only when<br />