motion for a temporary restraining order (PDF) - Denver Post Blogs

motion for a temporary restraining order (PDF) - Denver Post Blogs

motion for a temporary restraining order (PDF) - Denver Post Blogs

- No tags were found...

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

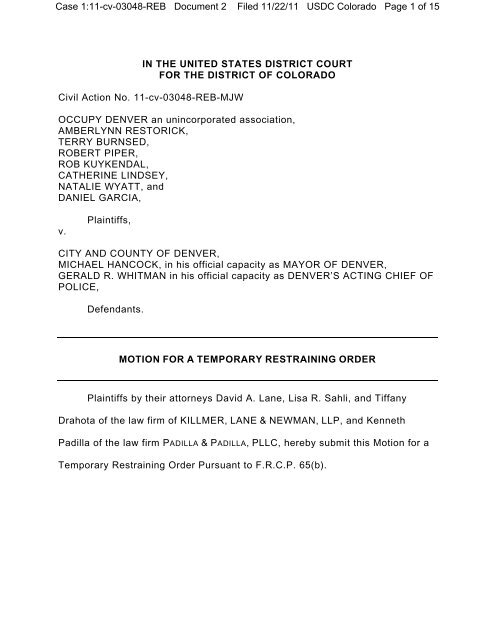

Case 1:11-cv-03048-REB Document 2 Filed 11/22/11 USDC Colorado Page 1 of 15<br />

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT<br />

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLORADO<br />

Civil Action No. 11-cv-03048-REB-MJW<br />

OCCUPY DENVER an unincorporated association,<br />

AMBERLYNN RESTORICK,<br />

TERRY BURNSED,<br />

ROBERT PIPER,<br />

ROB KUYKENDAL,<br />

CATHERINE LINDSEY,<br />

NATALIE WYATT, and<br />

DANIEL GARCIA,<br />

v.<br />

Plaintiffs,<br />

CITY AND COUNTY OF DENVER,<br />

MICHAEL HANCOCK, in his official capacity as MAYOR OF DENVER,<br />

GERALD R. WHITMAN in his official capacity as DENVER’S ACTING CHIEF OF<br />

POLICE,<br />

Defendants.<br />

MOTION FOR A TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER<br />

Plaintiffs by their attorneys David A. Lane, Lisa R. Sahli, and Tiffany<br />

Drahota of the law firm of KILLMER, LANE & NEWMAN, LLP, and Kenneth<br />

Padilla of the law firm PADILLA & PADILLA, PLLC, hereby submit this Motion <strong>for</strong> a<br />

Temporary Restraining Order Pursuant to F.R.C.P. 65(b).

Case 1:11-cv-03048-REB Document 2 Filed 11/22/11 USDC Colorado Page 2 of 15<br />

I. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND<br />

All statements of fact set <strong>for</strong>th in the previously filed Complaint are hereby<br />

incorporated into this Brief as though set <strong>for</strong>th fully herein 1 .<br />

II.<br />

PARTIES<br />

All statements of fact regarding the parties set <strong>for</strong>th in the previously filed<br />

Complaint are hereby incorporated into this Brief as though set <strong>for</strong>th fully herein.<br />

Furthermore, all Plaintiffs have standing as they have been injured by the<br />

conduct complained of in this <strong>motion</strong> 2 .<br />

III.<br />

LEGAL ARGUMENT<br />

A. Plaintiffs Have a Particularly Strong Basis For Meeting The<br />

Temporary Restraining Order and Preliminary Injunction Standards in<br />

a First Amendment Case<br />

Defendants’ selective en<strong>for</strong>cement of certain municipal ordinances against<br />

Occupy <strong>Denver</strong> protesters and their supporters, including Plaintiffs, constitutes<br />

retaliation in violation of their First Amendment rights to free expression and<br />

assembly and to petition their government <strong>for</strong> a redress of grievances.<br />

Defendant’s conduct similarly deters the exercise of legitimate constitutionally<br />

protected activity. Defendants’ unconstitutional retaliation creates a strong<br />

presumption that a <strong>temporary</strong> <strong>restraining</strong> <strong>order</strong> should issue.<br />

1 All factual statements in this <strong>motion</strong> as well as in the Complaint will be supported by<br />

sworn witness testimony at a hearing in this matter.<br />

2 Douglas Friednash, the <strong>Denver</strong> City Attorney, has been emailed the Complaint in this<br />

case and has acknowledged receipt thereof to counsel in an email yet he nevertheless<br />

insisted upon personal service which has now been completed. He is also being emailed<br />

a copy of this pleading.<br />

-2-

Case 1:11-cv-03048-REB Document 2 Filed 11/22/11 USDC Colorado Page 3 of 15<br />

To establish a First Amendment retaliation claim, a plaintiff must show<br />

that (1) he was engaged in constitutionally protected activity, (2) the<br />

government’s actions caused him injury that would chill a person of ordinary<br />

firmness from continuing to engage in that activity, and (3) the government’s<br />

actions were substantially motivated as a response to his constitutionally<br />

protected conduct. Howards v. McLaughlin, 634 F.3d 1131, 1144 (10th Cir.<br />

2011); see also Nielander v. Board of County Com’rs of County of Republic,<br />

Kansas, 582 F.3d 1155 (10th Cir. 2009).<br />

A Plaintiff in a First Amendment case must meet four conditions to obtain<br />

a Temporary Restraining Order: A Plaintiff must show that (1) he will suffer<br />

irreparable harm unless the injunction issues; (2) there is a substantial likelihood<br />

the Plaintiff ultimately will prevail on the merits; (3) the threatened injury to the<br />

Plaintiff outweighs any harm the proposed injunction may cause the opposing<br />

party; and (4) the injunction would not be contrary to the public interest. Am.<br />

Civil Liberties Union v. Johnson, 194 F.3d 1149, 1155 (10th Cir. 1999); see also<br />

Lundgrin v. Claytor, 619 F.2d 61, 63 (10th Cir. 1980); Heideman v. S. Salt Lake<br />

City, 348 F.3d 1182, 1189 (10th Cir. 2003). In a First Amendment case, the<br />

second condition—likelihood of success on the merits—plays a decisive role.<br />

Plaintiffs’ likelihood of success on the merits is especially strong here, because<br />

Defendants’ selective en<strong>for</strong>cement of the <strong>Denver</strong> municipal ordinances<br />

unquestionably retaliates against, and thereby violates, Plaintiffs’ First<br />

Amendment Rights.<br />

B. Plaintiffs Are Likely to Succeed on the Merits Because Defendants’<br />

Selective En<strong>for</strong>cement of <strong>Denver</strong> Municipal Ordinances §§ 39-3 54-71,<br />

-3-

Case 1:11-cv-03048-REB Document 2 Filed 11/22/11 USDC Colorado Page 4 of 15<br />

54-482, and 49-246 Retaliates Against Plaintiffs <strong>for</strong> the Exercise of Their<br />

First Amendment Rights<br />

Since September 2011, Plaintiffs have exercised, have witnessed the<br />

exercising of, or wish to exercise, their First Amendment rights in support of the<br />

Occupy <strong>Denver</strong> movement by sitting-in and picketing Lincoln and Civic Center<br />

Parks; honking their car horns; stopping on the side of the road to donate to the<br />

protesters or to simply show their support; and placing small items on the<br />

sidewalks nearby the Occupy <strong>Denver</strong> protests. Since October 13, 2011,<br />

Defendants have selectively en<strong>for</strong>ced <strong>Denver</strong> Revised Municipal Code § 54-71<br />

(the “no horn-honking ordinance”), § 54-482 (the “no stopping ordinance”), § 49-<br />

246 (the “right-of-way ordinance”) and § 39-3 (the “park curfew ordinance”) in an<br />

increasingly severe, systematic ef<strong>for</strong>t to silence the Occupy <strong>Denver</strong> movement.<br />

Defendants’ en<strong>for</strong>cement has been substantially motivated as a response to<br />

Plaintiffs’ exercise of their First Amendment rights in support of Occupy <strong>Denver</strong>,<br />

and has reasonably chilled Plaintiffs from continuing to exercise their First<br />

Amendment rights in support of Occupy <strong>Denver</strong>. Plaintiffs have a substantial<br />

likelihood of prevailing on the merits of a First Amendment retaliation claim.<br />

Notably, to obtain a <strong>temporary</strong> <strong>restraining</strong> <strong>order</strong>, “it is not necessary that the<br />

plaintiff’s right to a final decision, after a trial, be absolutely certain, wholly<br />

without doubt; if the other elements are present (i.e., the balance of hardships<br />

tips decidedly toward plaintiff), it will ordinarily be enough that the plaintiff has<br />

raised questions going to the merits so serious, substantial, difficult and doubtful<br />

as to make them a fair ground <strong>for</strong> litigation and thus <strong>for</strong> more deliberate<br />

investigation.” Lundgrin v. Claytor, 619 F.2d 61, 63 (10th Cir. 1980).<br />

-4-

Case 1:11-cv-03048-REB Document 2 Filed 11/22/11 USDC Colorado Page 5 of 15<br />

Plaintiffs here have more than met this test.<br />

i. Plaintiffs’ Have A First Amendment Right to Sit-In and<br />

Picket to Express Their Support <strong>for</strong> Occupy <strong>Denver</strong> and<br />

the Selective En<strong>for</strong>cement of the Park Curfew Ordinance<br />

Has Chilled The Plaintiffs’ Exercise of That Right.<br />

The First Amendment protects “speech,” which includes expressive<br />

conduct. See United States v. Grace, 461 U.S. 171, 176 (1983). To determine<br />

whether particular conduct is communicative such to fall within the protection of<br />

the First Amendment, courts consider two elements: (1) “whether an intent to<br />

convey a particularized message was present,” and (2) “whether the likelihood<br />

was great that the message would be understood by those who viewed it.”<br />

Texas v. Johnson, 491 U.S. 397, 404 (1989) (upholding the First Amendment<br />

right to burn the American flag during a protest rally).<br />

Sit-ins and picketing such as Plaintiffs’ in Lincoln and Civic Center Parks<br />

has long been deemed expressive conduct protected by the First Amendment.<br />

For example, the Supreme Court has extended First Amendment protection to<br />

the wearing of armbands by students to protest U.S. military involvement in<br />

Vietnam, Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, 393<br />

U.S. 503, 505 (1969); a sit-in by African-Americans in a “whites only” area to<br />

protest segregation, Brown v. Louisiana, 383 U.S. 131, 141-42 (1966); the<br />

wearing of American military uni<strong>for</strong>ms in protest of American involvement in<br />

Vietnam, Schacht v. United States, 398 U.S. 58 (1970), and even picketing in<br />

support of a wide variety of causes, see, e.g., Food Employees v. Logan Valley<br />

Plaza, Inc, 391 U.S. 308, 313-314 (1968); Grace, 461 U.S. at 176. Notably, sit-<br />

-5-

Case 1:11-cv-03048-REB Document 2 Filed 11/22/11 USDC Colorado Page 6 of 15<br />

ins such as that in Brown v. Lousiana were granted First Amendment protection<br />

despite the fact that such sit-ins technically violated the law.<br />

Plaintiffs and their Occupy <strong>Denver</strong> cohorts are no different than the civil<br />

rights and war protesters that preceded them. Their conduct is expressive and<br />

protected by the First Amendment: they are sitting-in, camping, and picketing in<br />

a public <strong>for</strong>um to protest economic inequality and publicize their demand <strong>for</strong> a<br />

more just and economically egalitarian society. Yet Defendants’ selective<br />

en<strong>for</strong>cement of the Park Curfew Ordinance disregards the fact that <strong>Denver</strong>’s<br />

Civic Center Park is rooted in the protection of this type of speech from<br />

governmental intrusion. Defendants’ selective en<strong>for</strong>cement of the Park Curfew<br />

Ordinance seeks only to chill Plaintiffs’ speech and has in fact done so by<br />

clearing some protesters from the park during evening hours and by intimidating<br />

protesters who would otherwise be present from attending Occupy <strong>Denver</strong>.<br />

Plaintiffs are fearful that they would be issued tickets <strong>for</strong> attending Occupy<br />

<strong>Denver</strong> protests during the hours prohibited by the Park Curfew Ordinance, even<br />

if they remained nearby, but outside of, the park. Defendants’ actions chilled<br />

the Plaintiffs’ firm commitment to engaging in protected First Amendment<br />

activity. Defendants, motivated by a desire to quash the Occupy <strong>Denver</strong> protest<br />

movement, selectively targeted Occupy <strong>Denver</strong> protesters in response to their<br />

expressive, constitutionally protected conduct. As such, Defendants have<br />

engaged in First Amendment retaliation.<br />

i. Plaintiffs Have a First Amendment Right to Temporarily Set<br />

Items Down on the Sidewalk Near the Occupy <strong>Denver</strong> Protests<br />

and The Selective En<strong>for</strong>cement of the Right-of-Way Ordinance<br />

Has Chilled the Plaintiffs’ Exercise of That Right.<br />

-6-

Case 1:11-cv-03048-REB Document 2 Filed 11/22/11 USDC Colorado Page 7 of 15<br />

Defendants have selectively en<strong>for</strong>ced the Right-of-Way Ordinance to<br />

prevent the placement of items on the sidewalk nearby the Occupy <strong>Denver</strong><br />

protests. “Sidewalks, of course, are among those areas of public property that<br />

traditionally have been held open to the public <strong>for</strong> expressive activities and are<br />

clearly within those areas of public property that may be considered, generally<br />

without further inquiry, to be public <strong>for</strong>um property.” See Grace, 461 U.S. at 179<br />

(finding the display of a sign with a written message on it expressive conduct<br />

protected by the First Amendment).<br />

Defendants have unconstitutionally attempted to close the sidewalks as a<br />

<strong>for</strong>um <strong>for</strong> Occupy <strong>Denver</strong> speech, by selectively en<strong>for</strong>cing the right-of-way<br />

ordinance against persons who set any item down while protesting at or<br />

associating with the Occupy <strong>Denver</strong> protests. “Even if an official’s actions would<br />

be ‘unexceptionable if taken on other grounds,’ when retaliation against<br />

Constitutionally-protected speech is the but-<strong>for</strong> cause of that action, this<br />

retaliation is actionable and subject to recovery.” See Howards, 634 F.3d at<br />

1143. The fact that the police may have had probable cause to arrest some of<br />

the protesters <strong>for</strong> violating this municipal ordinance is not fatal to Plaintiffs’ claim<br />

that the <strong>Denver</strong> Police are in fact retaliating against Plaintiffs, and others, <strong>for</strong><br />

exercising their Constitutional rights. Id. at 1145 (holding that “the presence of<br />

probable cause is not fatal to Mr. Howards’ First Amendment retaliation claim).<br />

In Howards, the Secret Service arrested a man in retaliation <strong>for</strong> the man’s<br />

statements to then-Vice-President Cheney. The defendants claimed that they<br />

arrested Mr. Howards not only because of his statements but also because they<br />

-7-

Case 1:11-cv-03048-REB Document 2 Filed 11/22/11 USDC Colorado Page 8 of 15<br />

had probable cause to believe Mr. Howards may have assaulted then-Vice-<br />

President Cheney. Howards was permitted to proceed to trial on his First<br />

Amendment retaliation claim, despite the fact that the Tenth Circuit found there<br />

was probable cause to arrest him. The defendants in this §1983 suit argued that<br />

when an officer has probable cause to arrest a plaintiff <strong>for</strong> any crime, it is<br />

irrelevant that a plaintiff may have engaged in protected speech prior to or<br />

during the arrest. Id. The Tenth Circuit rejected this argument, specifically<br />

declining to extend a “no probable-cause” requirement to First Amendment<br />

retaliation cases. Id. at 1148.<br />

In this case, Plaintiffs were engaged in expressive protest activities in a<br />

public <strong>for</strong>um. Plaintiffs watched the <strong>Denver</strong> police issue tickets to other<br />

protesters <strong>for</strong> merely placing items on the sidewalk, while protesting or to<br />

express support <strong>for</strong> the protests. Plaintiffs became fearful that the police would<br />

soon issue tickets to them. Motivated by a desire to silence the Occupy <strong>Denver</strong><br />

movement, Defendants retaliated against, and thereby chilled the Plaintiffs’ firm<br />

commitment to press ahead in the exercise of First Amendment rights as well as<br />

those of others who have observed Defendant’s unlawful conduct. Defendants<br />

thereby engaged in First Amendment retaliation.<br />

ii.<br />

Plaintiffs Have a First Amendment Right to Donate to Occupy<br />

<strong>Denver</strong> and The Selective En<strong>for</strong>cement of the No-Stopping<br />

Ordinance Has Chilled the Plaintiffs’ Exercise of That Right.<br />

The en<strong>for</strong>cement of the No Stopping Ordinance against Plaintiffs, supporters<br />

of Occupy <strong>Denver</strong>, should also be restrained. The retaliatory selective<br />

en<strong>for</strong>cement by Defendants violates Plaintiffs’ First Amendment rights of political<br />

-8-

Case 1:11-cv-03048-REB Document 2 Filed 11/22/11 USDC Colorado Page 9 of 15<br />

association and expression because Plaintiffs’ wished to donate money,<br />

clothing, and other items to support the Occupy <strong>Denver</strong> protesters. Plaintiffs’<br />

desire to donate to express their agreement with the political and social goals of<br />

the Occupy <strong>Denver</strong> movement.<br />

“The First Amendment af<strong>for</strong>ds the broadest protection to such political<br />

expression in <strong>order</strong> ‘to assure (the) unfettered interchange of ideas <strong>for</strong> bringing<br />

about of political and social changes desired by the people.’” Buckley v. Valeo,<br />

424 U.S. 1, 15 (1976) (quoting Roth v. United States, 354 U.S. 476, 484 (1957)).<br />

Accordingly, the First Amendment protects political association as well as<br />

political expression. Buckley at 15. Spending money <strong>for</strong> political ends falls within<br />

the First Amendment’s protection of speech and political association. See<br />

Federal Election Commission v. Colorado Republican Federal Campaign<br />

Committee, 533 U.S. 431, 442 (2001) (citing Buckley, 424 U.S. at 14-23).<br />

Here, Plaintiffs momentarily stopped to donate to the Occupy <strong>Denver</strong><br />

protesters. Such conduct was constitutionally protected activity; and, but <strong>for</strong> the<br />

fact that this brief stopping was to support the Occupy <strong>Denver</strong> protesters,<br />

Defendants would not have en<strong>for</strong>ced the No Stopping Ordinance. The Plaintiffs<br />

did not, or would not have, impeded traffic or obstructed the roadway <strong>for</strong><br />

pedestrians or other vehicles. Plaintiffs noticed <strong>Denver</strong> Police issuing tickets to<br />

people briefly stopping to make donations to the protesters. Once Plaintiffs saw<br />

this, they became fearful that the Police would issue tickets to them if they made<br />

donations to the Occupy <strong>Denver</strong> protesters. Ultimately, Plaintiffs stopped making<br />

donations to the protesters to avoid being ticketed. Defendants are thus<br />

-9-

Case 1:11-cv-03048-REB Document 2 Filed 11/22/11 USDC Colorado Page 10 of 15<br />

selectively en<strong>for</strong>cing the No-Stopping Ordinance to retaliate against the<br />

Plaintiffs, and others, <strong>for</strong> exercising their First Amendment rights. “Even if an<br />

official’s actions would be ‘unexceptionable if taken on other grounds,’ when<br />

retaliation against Constitutionally-protected speech is the but-<strong>for</strong> cause of that<br />

action, this retaliation is actionable and subject to [First Amendment] recovery.”<br />

See Howards, 634 F.3d at 1143.<br />

iii.<br />

Plaintiffs Have A First Amendment Right to Honk Their Horn to<br />

Express Support <strong>for</strong> Occupy <strong>Denver</strong> and the Selective<br />

En<strong>for</strong>cement of the No-Honking Ordinance Has Chilled The<br />

Plaintiffs’ Exercise of That Right.<br />

Like those who express support <strong>for</strong> Occupy <strong>Denver</strong> by sitting-in or<br />

picketing, those who express support by honking their car horns engage in<br />

speech protected by the First Amendment. Plaintiffs intended to convey a<br />

message when they briefly honked their horns: to support and energize<br />

protesters with the elevated sound of their car horn. Occupy <strong>Denver</strong> protesters,<br />

as well as the police, understood this intent. The protesters understood the<br />

intent of the car horns because when they heard the horns honking, the<br />

protesters’ spirits elevated; and frequently the protesters communicated back in<br />

the <strong>for</strong>m of cheering. Furthermore, the police clearly understood the horn<br />

honking to be in support of the protesters. That is exactly why they began<br />

setting up police cars to pull over anyone who honked in support of the<br />

protesters. Thus, honking a horn as an expression of solidarity constitutes<br />

expressive conduct protected by the First Amendment. See Goedert v. City of<br />

Ferndale, 596 F.Supp.2d 1027, 1030-31 (E.D. Mich. 2008) (deeming horn-<br />

-10-

Case 1:11-cv-03048-REB Document 2 Filed 11/22/11 USDC Colorado Page 11 of 15<br />

honking in support of protesters to be speech protected by the First<br />

Amendment).<br />

Honking a horn to express support <strong>for</strong> protesters squarely falls within the<br />

protection of the First Amendment, and Defendants retaliated against Plaintiffs<br />

<strong>for</strong> that speech when they issued citations <strong>for</strong> the No Horn Honking Ordinance.<br />

Once Plaintiffs noticed that the police were ticketing cars <strong>for</strong> giving support to<br />

the protesters by way of car horn, the Plaintiffs became fearful that they police<br />

would ticket them as well. This caused Plaintiffs to stop honking in support of<br />

the Occupy <strong>Denver</strong> protesters. The motivation behind the selective en<strong>for</strong>cement<br />

of the horn honking municipal provision is to retaliate against the Plaintiffs <strong>for</strong><br />

exercising their First Amendment rights. The law is well-settled that “the First<br />

Amendment prohibits government officials from subjecting an individual to<br />

retaliatory actions, including criminal prosecutions, <strong>for</strong> speaking out.” See<br />

Howards, 634 F.3d at 1143. Defendants must be restrained from ticketing those<br />

who honk their horns in support of the protesters because the practice inflicts<br />

irreparable harm on the Plaintiffs and is illegally motivated by a desire to<br />

retaliate against the exercise of the First Amendment.<br />

C. A Temporary Restraining Order Must Issue Because Plaintiffs Are<br />

Suffering Irreparable Harm, and the Balance of the Harms Results in<br />

Plaintiffs’ Favor.<br />

Once Plaintiffs have shown that their freedom of speech is burdened, as<br />

Plaintiffs have here, the other injunction conditions will typically be met. Where<br />

First Amendment rights are burdened, there is a presumption of irreparable<br />

harm. See Cmty. Communications v. City of Boulder, 660 F.2d 1370, 1376 (10th<br />

-11-

Case 1:11-cv-03048-REB Document 2 Filed 11/22/11 USDC Colorado Page 12 of 15<br />

Cir. 1981); Johnson, 194 F.3d at 1163. The reason <strong>for</strong> the presumption is selfevident.<br />

As the Supreme Court put it, “[t]he loss of First Amendment freedoms,<br />

<strong>for</strong> even minimal periods of time, unquestionably constitutes irreparable injury.”<br />

Elrod v. Burns, 427 U.S. 347, 373-74 (1976); see also Utah Licensed Beverage<br />

Ass’n v. Leavitt, 256 F.3d 1061, 1076 (10th Cir. 2001) (court assumes<br />

irreparable injury where there is a deprivation of speech rights). Plaintiffs are<br />

currently suffering irreparable harm and will undoubtedly continue to suffer<br />

irreparable harm unless the <strong>restraining</strong> <strong>order</strong> issues to stop the police from<br />

en<strong>for</strong>cing <strong>Denver</strong> municipal ordinances in retaliation <strong>for</strong> Plaintiffs’ exercise of<br />

their First Amendment rights.<br />

The irreparable injury to the Plaintiffs, absent a <strong>temporary</strong> <strong>restraining</strong><br />

<strong>order</strong>, far outweighs any alleged harm to the defendants if a <strong>restraining</strong> <strong>order</strong><br />

issues. The balance of harms test will most often be met in a First Amendment<br />

case where a plaintiff demonstrates a likelihood of success on the merits as<br />

Plaintiffs have done herein. A threatened injury to Plaintiffs’ constitutionally<br />

protected speech will usually outweigh the harm, if any, the defendants may<br />

incur from being unable to en<strong>for</strong>ce what is in all likelihood an unconstitutional<br />

statute or directive. See ACLU v. Johnson, 194 F.3d at 1163. This is especially<br />

true where <strong>restraining</strong> Defendants would actually give the <strong>Denver</strong> Police time to<br />

fight crime rather than trample on First Amendments rights of people engaged in<br />

constitutionally protected political speech. At a minimum, Defendants will suffer<br />

no injury if <strong>order</strong>ed to refrain from retaliating against people <strong>for</strong> supporting<br />

Occupy <strong>Denver</strong>.<br />

-12-

Case 1:11-cv-03048-REB Document 2 Filed 11/22/11 USDC Colorado Page 13 of 15<br />

Finally, Plaintiffs also satisfy the “public interest test” because <strong>restraining</strong><br />

<strong>order</strong>s and injunctions blocking state action that would otherwise interfere with<br />

First Amendment rights are consistent with the public interest. Elam Constr. v.<br />

Reg. Transp. Dist., 129 F.3d 1343, 1347 (10th Cir.1997) (“The public<br />

interest...favors plaintiffs’ assertion of their First Amendment rights.”); Utah<br />

Licensed Beverage Ass’n, 256 F.3d at 1076; Johnson, 194 F.3d at 1163; Million<br />

Man March v. Cook, 922 F. Supp. 1494, 1501 (D. Colo. 1996) (stating that “it is<br />

axiomatic that the preservation of First Amendment rights serves everyone’s<br />

best interest.”).<br />

IV.<br />

CONCLUSION<br />

As Justice Brandeis once observed:<br />

Those who won our independence believed that the final end of the State<br />

was to make men free to develop their faculties, and that, in its<br />

government, the deliberative <strong>for</strong>ces should prevail over the arbitrary. They<br />

valued liberty both as an end, and as a means. They believed liberty to be<br />

the secret of happiness, and courage to be the secret of liberty. They<br />

believed that freedom to think as you will and to speak as you think are<br />

means indispensable to the discovery and spread of political truth; that,<br />

without free speech and assembly, discussion would be futile; that, with<br />

them, discussion af<strong>for</strong>ds ordinarily adequate protection against the<br />

dissemination of noxious doctrine; that the greatest menace to freedom is<br />

an inert people; that public discussion is a political duty, and that this<br />

should be a fundamental principle of the American government.<br />

Whitney v. Cali<strong>for</strong>nia, 274 U.S. 357, 375 (1927) (Brandeis, J., concurring).<br />

-13-

Case 1:11-cv-03048-REB Document 2 Filed 11/22/11 USDC Colorado Page 14 of 15<br />

For the reasons stated, Plaintiffs respectfully request that this Court hold<br />

a hearing on this Motion <strong>for</strong> a Temporary Restraining Order, grant this Motion<br />

<strong>for</strong> a Temporary Restraining Order and prohibit Defendants from en<strong>for</strong>cing<br />

<strong>Denver</strong> Revised Municipal Codes §§ 49-246, 54-71, and 54-482 against the<br />

Occupy <strong>Denver</strong> Protesters and Supporters.<br />

Dated this 22 nd day of November 2011.<br />

KILLMER, LANE & NEWMAN, LLP<br />

s/ David A. Lane<br />

David A. Lane<br />

Lisa R. Sahli<br />

Tiffany Drahota<br />

1543 Champa Street, Suite 400<br />

<strong>Denver</strong>, CO 80202<br />

(303) 571-1000<br />

dlane@kln-law.com<br />

lsahli@kln-law.com<br />

tdrahota@kln-law.com<br />

Padilla & Padilla, PLLC<br />

s/ Kenneth A. Padilla<br />

Kenneth A. Padilla<br />

1753 Lafayette Street<br />

<strong>Denver</strong>, CO 80218<br />

Phone: (303) 832-7145<br />

Facsimile:(303) 832-7147<br />

E-mail: Padillaesq@aol.com<br />

ATTORNEYS FOR PLAINTIFFS<br />

-14-

Case 1:11-cv-03048-REB Document 2 Filed 11/22/11 USDC Colorado Page 15 of 15<br />

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE<br />

I HEREBY CERTIFY that on this 22 nd day of November, 2011, a true and correct<br />

copy of the <strong>for</strong>egoing BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR TEMPORARY<br />

RESTRAINING ORDER was filed with the Clerk of Court using the CM/ECF system<br />

and was emailed to the <strong>Denver</strong> City Attorney.<br />

Doug Friednash<br />

doug.friednash@denvergov.org<br />

s/ David A. Lane<br />

-15-