The Architectural Historian Issue 1

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>The</strong><br />

ARCHITECTURAL<br />

HISTORIAN<br />

<strong>Issue</strong> 1, June 2015<br />

ISSN 2056–9181<br />

IN OUR FIRST ISSUE: A fresh look at Hampton Court Palace | <strong>The</strong> making of Trerice |<br />

Collections in Focus | Exhibitions | In Profile | Book Reviews

fl{..rrrECruRAL<br />

fssue 4June zor5<br />

Message from<br />

the Editor...<br />

EditorialTeam<br />

Magazine Editor<br />

Kay Carson<br />

magazine@sahgb.org.uk<br />

Book Reviews Editor<br />

Cat Gray<br />

reviewseditor@sa hg b.org.uk<br />

Production<br />

Oblong Creative Ltd<br />

+r6B Thorp Arch Estate<br />

Wetherby<br />

LSz: zFG<br />

United Kingdom<br />

No material may be reproduced in part or<br />

whole without the express permission of the<br />

publisher.<br />

icr zor5 Society of <strong>Architectural</strong> <strong>Historian</strong>s of<br />

Great Britain Limited by guarantee. Registered<br />

Number 8ro735 England Registered as a Charity<br />

No.236432 Registered Office: Beech House,<br />

Cotswold Avenue, Lisvane, Cardiff CFrq oTA<br />

(ompetition rules<br />

<strong>The</strong> Mystery Photo Competition closes on<br />

September 30,2o1s. A National Book Token<br />

to the value of rzo will be awarded to the<br />

winner, i.e. the sender of the first correct<br />

entry drawn at random after the closing date.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Editor's decision is final. No<br />

correspondence will be entered into. Prizes<br />

are as stated and no cash in lieu or<br />

alternative will be offered to UK-based<br />

entrants. An alternative book token to the<br />

same value may be offered if the winner lives<br />

permanently outside the UK and cannot<br />

purchase items with a National Book Token.<br />

<strong>The</strong> winner will be notified by post,<br />

telephone or e-mail. <strong>The</strong> name of the winner<br />

will be available on request. Entrants must be<br />

members of the Society of <strong>Architectural</strong><br />

History of Great Britain.<br />

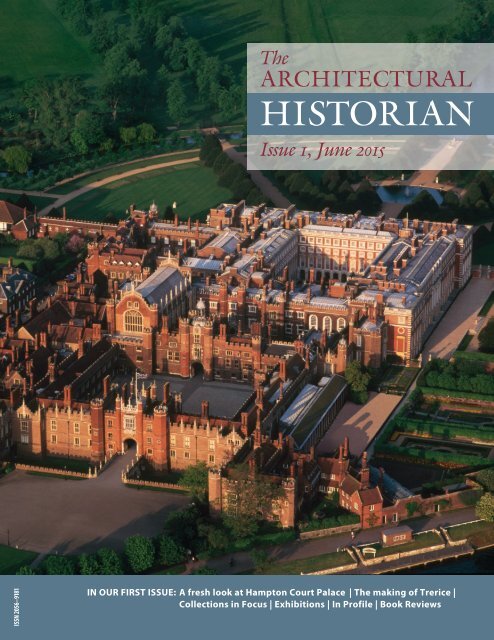

Cover imoge Aerial view of Hampton (ourt Palace<br />

o Historic Royal Palaces<br />

EiGil<br />

ffi<br />

Hello and welcome to the very first issue of <strong>The</strong> <strong>Architectural</strong> <strong>Historian</strong>, the new,<br />

full-colour magazine from the Society of <strong>Architectural</strong> <strong>Historian</strong>s of Great Britain. Our<br />

publication will be with you twice a year and has been designed with all of you in<br />

mind - the members. Within the pages of <strong>The</strong> <strong>Architectural</strong> <strong>Historian</strong>,you're always<br />

likely to find a mix of voices from all types of people - students, curators, academics,<br />

collections managers, writers, archivists, and many more - who have (at least!) one<br />

thing in common: their interest in the history of architecture. As well as two fantastic<br />

features, each issue will bring you our new, regular columns such as'A Week in the<br />

Life ...', which turns its spotlight on one person's day-to-day involvement in the field<br />

of architectural history, while 'Classic Book Review' revisits a well-known text to<br />

assess its relevance for today's historian, and 'Collections in Focus'aims to showcase<br />

the architectural objects held in various collections around the United Kingdom. ln<br />

addition, there will be reports on graduate student research activities; coverage of<br />

exhibitions relating to architectural history; and words and pictures from the<br />

Society's recent study days. Readers of the previous publication, the Neurs/etter, will<br />

notice two familiar features joining us at <strong>The</strong> <strong>Architectural</strong> <strong>Historian</strong>: our substantial<br />

Book Reviews section will now appear in full colour, with images from new<br />

publications featuring alongside reviewers'texq and for our amusement, Nicholas<br />

Cooper has produced a series of limericks, appropriately entitled 'A few more (faintly<br />

flickering) Lamps of Architecture' in tribute to their clerihew predecessors the'Well<br />

Trimmed Lamps'. Are you eagle-eyed when it comes to identifying buildings? Please<br />

enter our mystery photo competition on Page i2 - you could win a National Book<br />

Token for ezo.<br />

I hope you enjoy our first 32 pages.<br />

Happy reading,<br />

Ka7<br />

Kay Carson, Editor<br />

lhe Alr/ritectutol Histortan wouldlike to thank the following contributors:<br />

Vanda Baweja<br />

James Bettley<br />

Laura Bowie<br />

Edward Bottoms<br />

James Campbell<br />

Katie Carmichael<br />

Nicholas Cooper<br />

Elain Harwood<br />

Gordon Higgott<br />

Paul Holden<br />

Daniel Jackson<br />

Kathryn Morrison<br />

Malcolm Thurlby<br />

Emma Wells<br />

torfurther information about the Society ofArchitectunl <strong>Historian</strong>s ofGreat Britain including details<br />

on how to become a membel, please visit oul website at www.sahgb.org.uk. More fiom oul new<br />

magazine can be found at www.thearchiteduralhistorian.org.uk.

COVER STORY<br />

<strong>The</strong> Lost Palace: Henry<br />

VIII’s Hampton Court<br />

With the 500th anniversary celebrations of<br />

Hampton Court Palace in full swing, curator<br />

DANIEL JACKSON explores new, tantalising<br />

clues to the site’s Tudor history.<br />

4 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Architectural</strong> <strong>Historian</strong> <strong>Issue</strong> One / June 2015

Hampton Court Palace is one of the most famous buildings in England and its association<br />

with Henry VIII has cemented its place in the minds of the public for several<br />

generations. However, if you go searching for evidence of Henry’s architectural<br />

patronage at Hampton Court it may help to bring a shovel!<br />

While the palace is most commonly associated with Henry, it is actually Cardinal Thomas Wolsey<br />

who was responsible for the majority of the preserved Tudor buildings. Although Henry spent ten<br />

years building elaborate extensions to the palace, in 1689 William III and Mary II decided that the,<br />

by then old fashioned, Tudor private apartments should be demolished and replaced with a<br />

magnificent new baroque palace. Luckily, despite the destruction orchestrated by Christopher<br />

Wren it is still possible to find glimpses of the lost Tudor palace. <br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Architectural</strong> <strong>Historian</strong> <strong>Issue</strong> One / June 2015 5

=_r=t+--=E=+----------------i:!.+^arE#i':<br />

=;_ _. fa::"- :1 iiE:r-= .e-j--.- < :-:_:r-qitiF --!=:j<br />

=<br />

La;._<br />

:-:r!<br />

t*<br />

;ir,l.).?J1X.-r-??}-s., l_:r.t]f S''i'

weeks of their coronation. <strong>The</strong>y found the<br />

location much to their liking, however they<br />

thought the palace itself was old fashioned<br />

and run down. <strong>The</strong>y commissioned<br />

Christopher Wren to design a new palace<br />

that could match the modern comforts to<br />

which they had become accustomed in the<br />

Netherlands. Though Wren’s initial plans<br />

called for the almost complete destruction of<br />

the Tudor palace, save for the Great Hall,<br />

these were, thankfully for us, revised. Wren’s<br />

final design however still involved the<br />

destruction of almost all the private<br />

apartments built by Henry. <strong>The</strong> redundant<br />

sections of the palace were levelled and all<br />

the material that could not be reused in the<br />

Whilst the two buildings shared<br />

a similar language, their style,<br />

form and massing were<br />

strikingly different.<br />

new building 3 was tipped into ditches and<br />

gravel pits to level the ground.<br />

William and Mary’s choice to preserve much<br />

of the Tudor palace and construct their new<br />

palace up against the old, gave Hampton<br />

Court a fascinating dual identity. Whilst the<br />

two buildings shared a similar language, with<br />

the strong red brickwork and stone detailing,<br />

their style, form and massing were strikingly<br />

different. It is a tribute to Wren’s skill as an<br />

architect, and perhaps Daniel Marot’s as a<br />

garden designer, that there are few areas<br />

where this ‘clash’ of styles could be seen<br />

from the ground.<br />

With the creation of this new baroque royal<br />

palace, Christopher Wren had destroyed<br />

much of Henry’s contribution to Hampton<br />

Court’s architectural inheritance. <strong>The</strong> most<br />

significant losses were the King’s Long<br />

Gallery, built initially by Wolsey but greatly<br />

extended 4 by Henry, the extensive Queen’s<br />

Private Apartments, and the Tudor Privy<br />

Garden, including the Watergate and a series<br />

Merged image of the Baroque and Tudor palaces from the east © Historic Royal Palaces<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Architectural</strong> <strong>Historian</strong> <strong>Issue</strong> One / June 2015 7

Foundations of the Queen’s private apartments exposed December 2014. Photograph taken by Claire Collins © Historic Royal Palaces<br />

of elaborate gothic towers and banqueting<br />

houses.<br />

When combined with the loss of the older<br />

section of the King’s Private Apartments in<br />

1730, 5 very little of the private space built and<br />

used by Henry survives. Whilst the Great Hall<br />

alone would form a remarkable legacy, the<br />

lost elements of Henry’s Hampton Court are<br />

a fascinating topic to consider. Luckily,<br />

despite losing the buildings themselves,<br />

there are numerous sources of information<br />

that provide clues to their original form and<br />

function. <strong>The</strong> surviving Tudor works<br />

accounts, a series of images from the late<br />

sixteenth and mid-seventeenth century and<br />

an outline plan showing the palace just<br />

before its destruction provide a solid<br />

documentary record. <strong>The</strong>re are also<br />

extensive archaeological remains preserved<br />

behind panelling and beneath floorboards<br />

that, when revealed, can shed further light<br />

on the lost palace.<br />

Hampton Court’s Tudor history has been the<br />

focus of much academic study over the past<br />

century. 6 Whilst we already have a good<br />

understanding of the design and layout of<br />

the Tudor private apartments there is still<br />

much to learn. Even seemingly minor<br />

maintenance projects can reveal exciting<br />

new information.<br />

During maintenance work in December 2014<br />

previously unseen remains of the Tudor<br />

Palace were revealed. Apartment 12 sits in<br />

the north east corner of the baroque palace<br />

and is now used by the Royal School of<br />

Needlework. Whilst carpenters were working<br />

to fix a bowing floor, they disturbed what<br />

they thought might be an earlier structure.<br />

Gary Evans, an archaeologist working for<br />

Oxford Archaeology, orchestrated the careful<br />

removal of several inches of accumulated<br />

dust and debris 7 from the site. This work<br />

revealed a large section of the foundations<br />

for the Tudor Queen’s Apartments.<br />

<strong>The</strong> architectural remains showed a number<br />

of different phases of building work, the<br />

destruction wrought by Wren and the later<br />

insertion of a large service trench. <strong>The</strong> thick<br />

red brick foundation running across the<br />

room marks the eastern elevation of the<br />

apartments built by Henry for Anne Boleyn,<br />

his second wife. <strong>The</strong> construction began<br />

only a month after Anne was crowned in<br />

1533, the project having to wait until Henry’s<br />

marriage to Katherine of Aragon had been<br />

officially annulled. <strong>The</strong> building accounts<br />

show that the foundations alone took ten<br />

months to measure out, excavate and<br />

construct. <strong>The</strong> two new ranges of<br />

apartments for Anne, when combined with<br />

the existing King’s Long Gallery to the south<br />

and a new connecting gallery to the west,<br />

would have formed a third courtyard<br />

creating a sense of unity in the eastern half<br />

of the palace.<br />

<strong>The</strong> bay window visible in the photograph<br />

butts up against the main foundations and it<br />

may have been a revision to the original<br />

design as envisaged by Henry and Anne. <strong>The</strong><br />

royal couple regularly visited Hampton Court<br />

to survey progress and it is not unreasonable<br />

to suspect the original design was modified<br />

between the laying of the foundations and<br />

8 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Architectural</strong> <strong>Historian</strong> <strong>Issue</strong> One / June 2015

the completion of the project. <strong>The</strong> building<br />

accounts make reference to the construction<br />

of a number of bay windows in the new<br />

Queen’s Apartments, though it is difficult to<br />

identify exact locations for these. Why the<br />

bay window was not more securely tied into<br />

the main foundations is difficult to<br />

understand.<br />

After the execution of Anne Boleyn in 1536<br />

Jane Seymour took her place as Henry’s<br />

Queen. Henry once again expanded his plans<br />

for the palace. <strong>The</strong> king ordered a new<br />

extension to the Queen’s Private Apartments<br />

to the north, in order to connect them with<br />

another suite of private apartments he was<br />

having constructed for his son, the soon to<br />

be born Prince Edward. Whilst this new<br />

phase of major construction work was taking<br />

place, the building accounts suggest<br />

numerous changes and alterations were<br />

happening within the apartments designed<br />

for Anne. It is possible that the bay window<br />

was added during this later phase of<br />

construction, though no evidence for this has<br />

been located within the building accounts.<br />

<strong>The</strong> bay window itself shows yet another<br />

phase of building activity. A thin wall has<br />

been built up against the original internal<br />

face of the window. This wall was built on<br />

top of a demolition deposit that contained a<br />

clay pipe made by John Rosse of Kingston<br />

between 1580 and 1610. <strong>The</strong> deposit also<br />

contained a significant quantity of ceramic<br />

floor tile. 8 <strong>The</strong> purpose of this feature may be<br />

revealed by considering the location of the<br />

structure. This entire section of the Queen’s<br />

Apartments was built out into the eastern<br />

extent of the Wolseyian moat. It is possible<br />

that, as the window was not tied into the<br />

main structure, at least at foundation level, it<br />

had already begun to show evidence of<br />

subsidence by the end of the sixteenth<br />

century and additional strengthening was<br />

deemed necessary. This could account for<br />

the addition of the inner wall and the<br />

presence of the ceramic floor tile in the<br />

underlying layer, having been broken out to<br />

allow access at foundation level.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se findings are still very new and research<br />

will continue over the coming years as we try<br />

to fit this new information into the existing<br />

picture of the lost Tudor palace. Key to this<br />

will be a comprehensive review of the<br />

surviving works accounts in light of the<br />

questions raised by these new structural<br />

remains.<br />

<strong>The</strong> complex architectural and social history<br />

of Hampton Court Palace continues to<br />

fascinate scholars and the public. <strong>The</strong> vast<br />

quantity of surviving documentary and<br />

archaeological evidence provides an<br />

invaluable insight into the extraordinary<br />

nature of over 500 years of change,<br />

development and destruction. Whilst many<br />

sites struggle with a paucity of evidence,<br />

Hampton Court is instead beset by a paucity<br />

of time available to consider the staggering<br />

quantity, and quality, of data. With every<br />

page of works accounts transcribed and<br />

archaeological excavation completed, we<br />

often find the number of new answers is<br />

equalled by the number of new questions.<br />

Daniel Jackson works for Historic Royal<br />

Palaces (HRP) as Curator of Historic Buildings<br />

at Hampton Court Palace. Trained as an<br />

archaeologist at the Universities of Bradford<br />

and Birmingham, he worked as a commercial<br />

archaeologist in the south-east of England<br />

before joining HRP in 2012. If you have any<br />

questions or comments about these new<br />

discoveries, or Hampton Court generally, feel<br />

free to get in touch via curators@hrp.org.uk.<br />

1 Despite efforts by both Daubeney and Wolsey it<br />

isn’t until 1531, under Henry VIII, that the Knights<br />

Hospitaller relinquish overall ownership of the site.<br />

2 For instance Cardinal John Morton, Bishop of Ely<br />

1479–86, and William Warham, Archbishop of<br />

Canterbury and Wolsey’s predecessor as Lord<br />

Chancellor.<br />

3 It appears that many of the larger pieces of<br />

Tudor stonework were reshaped and incorporated<br />

into the new building.<br />

4 This extension includes the addition of a timber<br />

framed third storey on top of the original two.<br />

5 When William Kent is commissioned to tear<br />

down the whole east range of Clock Court and<br />

build a new ‘Neo-Gothic’ range for the Duke of<br />

Cumberland.<br />

6 For a comprehensive overview and bibliography<br />

see Simon Thurley’s Hampton Court: A social and<br />

architectural history 2003 (currently out of print).<br />

7 <strong>The</strong> deposit was particularly deep here due to a<br />

later culvert that had been excavated through the<br />

space, with the up-cast partially redeposited within<br />

the cut and partially spread across the ground<br />

surface.<br />

8 Unfortunately we are yet to receive any further<br />

dating evidence from the floor tile or any of the<br />

other archaeological finds from within the bay<br />

window.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Baroque South and East Fronts of the palace, as viewed from the Great Fountain Garden. © Historic Royal Palaces<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Architectural</strong> <strong>Historian</strong> <strong>Issue</strong> One / June 2015 9

COLLECTIONS IN FOCUS<br />

<strong>The</strong> Otto Koenigsberger<br />

Papers, AA Archives<br />

Archivist at AA Archives, Edward Bottoms, explains how a recent bequest has provided an<br />

engaging insight into post-war and post-colonial planning<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Architectural</strong> Association Archives<br />

were established in 2009 with the aim<br />

of making accessible the AA’s wealth<br />

of historic membership and educational<br />

records dating back to the 1840s. Whilst<br />

cataloguing of our holdings has proceeded<br />

apace, one of the largest discrete collections<br />

which remains, as yet, uncatalogued is the<br />

Otto Koenigsberger Archive. Bequeathed to<br />

the AA Archive in 2012 by Renate<br />

Koenigsberger, Otto’s widow, the papers<br />

trace in minute detail Otto’s background and<br />

remarkable career – from his training and<br />

early work in 1930s Berlin, through to his<br />

eventual settling in London, where he was<br />

instrumental in setting up and leading the<br />

AA’s highly influential ‘Department of<br />

Tropical Architecture’. Alongside<br />

documenting this personal odyssey, the<br />

papers also provide a unique window on the<br />

post-war, post-colonial planning scene, with<br />

extensive materials relating to Otto’s<br />

international planning advisory work and<br />

participation in numerous global UN<br />

missions and programmes.<br />

<strong>The</strong> survival of such a comprehensive archive<br />

is astonishing – even Otto’s student days in<br />

the 1920s and 30s are documented and<br />

include not only his ‘Belegbuchblatt’ from<br />

the Berlin Technische Hochshcule (TU Berlin),<br />

10 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Architectural</strong> <strong>Historian</strong> <strong>Issue</strong> One / June 2015<br />

signed by Hans Poelzeg, Bruno Taut and his<br />

other tutors, but also the drawings for his<br />

1931 graduation project for a zoological<br />

garden (for which he was awarded the TU<br />

Bronze medal). With the rise of the Nazi Party,<br />

Koenigsberger left for Egypt, working as an<br />

archaeologist at the Ludwig-Borchardt<br />

Institute (now Swiss Institute, Cairo).<br />

Amongst the extensive sets of surviving<br />

Otto Koenigsberger, 1931, TU Berlin graduation<br />

project, ‘Design for Zoological Gardens’. AA Archives<br />

survey drawings and research notes for<br />

temple sites along the West bank of Luxor<br />

can be found a wonderful series of<br />

photographs of the archaeological digs and<br />

their environs.<br />

In 1939 Koenigsberger gained the post of<br />

Government Architect of Princely State of<br />

Mysore and was responsible for designing a<br />

wide range of buildings including the Central<br />

College for Women, Nagpur (1942) and<br />

Victory Hall, Bangalore (1947) – drawings for<br />

which all survive in his archive. He was also<br />

privately employed by the Tata family,<br />

undertaking urban planning schemes for<br />

Mithapur, Bhadravati and drawing up the<br />

1945 master-plan for Jamshedpur. Over 150<br />

photographs and drawings for the majority<br />

of these projects remain within Otto’s papers,<br />

together with a small series of commissions<br />

from the Maharaja. Most eye-catching of<br />

these latter designs are drawings for<br />

improvements to Mysore Palace, for the<br />

Maharaja’s private train and for a royal<br />

pavilion on top of the Krishna Raja Sangara<br />

Dam!<br />

Following Indian Independence, Jawaharlal<br />

Nehru appointed Koenigsberger as Federal<br />

Director of Housing, with the key task of<br />

resettling refugees displaced by Partition, a<br />

role that saw Otto involved in the planning of<br />

the New Towns of Gandhidham and<br />

Bhubneshwar – unique studies and drafts for<br />

which can also be found amongst his papers.<br />

Central to Koenigsberger’s plans was a<br />

scheme for a Government Housing Factory in<br />

Delhi which was to produce mass<br />

pre-fabricated housing. <strong>The</strong> acrimonious<br />

Archaeologists Ludwig Borchardt, Herbert Ricke and others, picnicking at Saqqara, 1933. AA Archives

failure of this project, voluminously detailed<br />

in the archive, was to lead to Koenigsberger’s<br />

eventual resignation and departure for<br />

Britain in 1951.<br />

In 1953 Otto was one of the key instigators<br />

and organisers of the landmark ‘Conference<br />

on Tropical Architecture’ (University College<br />

London, 1953), from which would<br />

subsequently emerge the AA’s<br />

groundbreaking ‘Department of Tropical<br />

Architecture’. Documentation within the<br />

Koenigsberger archives and the AA’s core<br />

collections reveal Otto’s role in setting up the<br />

department and proposing Maxwell Fry as its<br />

first head – a position which Koenigsberger<br />

was to assume just two years later. <strong>The</strong><br />

methodology and influence of this<br />

pioneering department have never been<br />

adequately studied, due to a paucity of<br />

archival material. It is now possible, however,<br />

to construct a clear idea of the post-graduate<br />

students attending the course and the<br />

network of countries from which they were<br />

drawn. Likewise, Koenigsberger’s lecture<br />

notes and curriculum planning serve to<br />

thoroughly document the pedagogy of the<br />

course. It was whilst running the Department<br />

that Otto articulated his influential concept<br />

of ‘action planning’ and developed research<br />

which would be eventually published in his<br />

classic textbook ‘Manual of Tropical Housing<br />

and Building’ (1974). A draft for an<br />

unpublished second volume to the ‘Manual’<br />

has tentatively been identified in the archive,<br />

alongside substantial documentation of the<br />

Department’s transferral to University<br />

College London, as the ‘Development<br />

Planning Unit’, in 1971.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Koenigsberger Archive also serves to<br />

shed significant light upon the transnational<br />

network of global experts in planning which<br />

emerged in the post-war, post-colonial<br />

world. Koenigsberger was involved in<br />

numerous UN missions and advisory<br />

programmes and initiatives, working<br />

alongside figures such as Charles Abrams<br />

and Vladimir Bodiansky, as a consultant to<br />

governments including those of Nigeria,<br />

Ghana, Singapore, Ceylon, Pakistan, the<br />

Philippines, Zambia, Brazil and Israel. <strong>The</strong><br />

related correspondence, draft reports and<br />

research materials constitute a treasure trove<br />

for scholars of the history of transnational<br />

planning.<br />

<strong>The</strong> AA Archives are currently applying for<br />

funding to catalogue this remarkable<br />

collection but it is intended that supervised<br />

access to the papers, albeit in their unsorted<br />

state, will be maintained throughout the<br />

process<br />

above left Otto<br />

Koenigsberger, 1942,<br />

‘Design for Central College<br />

for Women, Nagpur’.<br />

AA Archives<br />

above right<br />

Government<br />

Pre-Fabricated Housing<br />

Factory, New Delhi,<br />

c. 1951. AA Archives<br />

left Otto Koenigsberger,<br />

c. 1950, ‘Plan for<br />

Gandhidham’. AA Archives<br />

Otto Koenigsberger, c. 1941, ‘Design for royal pavilion on the top of the Krishna Raja<br />

Sangara Dam’. AA Archives<br />

Otto Koenigsberger, 1948, ‘Draft plan for Mithapur’. AA Archives<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Architectural</strong> <strong>Historian</strong> <strong>Issue</strong> One / June 2015 11

First edition of Suffolk (<strong>The</strong> Buildings of<br />

England series) was published in 1961<br />

© Penguin Books Ltd<br />

CLASSIC BOOK REVIEW<br />

Hall I have given the owner’s London address<br />

as I understand that he is at Assington only<br />

occasionally’), letters were written to the<br />

owners, and visits arranged (‘Sotterley Hall.<br />

Written. Col. Barne. OK but as much notice as<br />

poss. and would like you to go to luncheon.’).<br />

Pevsner was back in London on 28 August, so<br />

can have spent only four weeks visiting the<br />

500 or so places in the county. <strong>The</strong>n began<br />

the process of further letters to librarians,<br />

archivists, architects and others, seeking<br />

information about what he had seen and<br />

also, in the case of some architects, about<br />

buildings which he had not seen and which<br />

they thought might be worthy of inclusion.<br />

<strong>The</strong>se mostly appear in the text in brackets,<br />

such as the secondary modern school at<br />

Woodbridge included at the suggestion of<br />

the county architect, E. J. Symcox. A further<br />

refinement of the text was provided by<br />

George McHardy who, on leave from the<br />

Bengal Chamber of Commerce and Industry<br />

in the summer of 1959, ‘visited 392 Suffolk<br />

churches with typescript . . . in hand [and]<br />

found more errors and omissions than I could<br />

count or would care to remember.’<br />

<strong>The</strong> volume was finally published early in<br />

1961, priced at 12/6 in paperback and 17/6 in<br />

hardback. <strong>The</strong> reddish brown cover of the<br />

paperback, designed by Hans Schmoller,<br />

included a decorative roundel by Berthold<br />

Wolpe based on a flushwork emblem from<br />

the porch of Woodbridge church; the jacket<br />

carried a rather grainy photograph of<br />

Flaxman’s sculpture ‘<strong>The</strong> Fury of Athamas’ at<br />

Ickworth. As always, the foreword invited<br />

users of the volume to point out omissions<br />

and mistakes, something the county archivist<br />

of West Suffolk must have done within days,<br />

for on 28 February 1961 Pevsner wrote to him:<br />

‘It is very discouraging indeed to realise that<br />

whatever trouble you take, the resident<br />

expert will always be able to find mistakes.’<br />

<strong>The</strong> second edition, revised by Enid Radcliffe,<br />

appeared in 1975 (although dated 1974), and<br />

the third edition, in two volumes, is<br />

published by Yale University Press in 2015.<br />

But that is no reason why owners of the first<br />

edition should not continue to treasure it. For<br />

the bibliophile, there is the sheer pleasure of<br />

handling a Penguin book of that era. <strong>The</strong><br />

paper and binding, assuming the volume has<br />

not been too heavily used, is still sound,<br />

which is remarkable in itself and more than<br />

can be said for most fifty-year-old<br />

paperbacks. Visually, the volume remains a<br />

delight, not just the cover but the text as<br />

well, also the responsibility of Schmoller –<br />

much thought went into the typography and<br />

layout, to help the reader make sense of<br />

what might otherwise be a daunting block of<br />

text. Only the reproduction of the black-andwhite<br />

photographs falls below present-day<br />

expectations. Photographs were not then, as<br />

they are now, specially commissioned, and<br />

much depended on what was available at<br />

the National Buildings Record (as it then<br />

was), but even so some of the photographs<br />

in Suffolk provide a valuable record of what<br />

can no longer be seen: the interior of Elveden<br />

Hall, for example, or the painting by William<br />

Dyce that was sold by Knodishall church in<br />

1983. It would be almost impossible now to<br />

take a photograph of Angel Hill, Bury<br />

St Edmunds, that did not include a single<br />

motor car.<br />

Pevsner has a reputation, largely undeserved,<br />

for dryness. This is partly because he praises<br />

and criticises rarely, so that when he does, his<br />

opinion is all the more telling. ‘Rather grim<br />

from the N’ sums up Mickfield well. On the<br />

other hand, ‘Long Melford church is one of<br />

the most moving parish churches of England,<br />

large, proud, and noble – large certainly with<br />

its length inside nave and chancel of 153 ft,<br />

proud certainly with the many<br />

commemorative inscriptions which<br />

distinguish it from all others, and noble also<br />

without question with the aristocratic<br />

proportions of the exterior of its nave and<br />

aisles.’ ‘Delightful’ is one of his favourite<br />

terms of praise, such as the font cover at<br />

Ufford, ‘a prodigious and delightful piece’, or<br />

Letheringham Mill, ‘a delightfully<br />

picturesque group’. His virtuoso (and<br />

unusually long) description of the roof at<br />

Needham Market is followed by the ‘bitter<br />

disappointment’ of the rest of the church,<br />

especially the S porch ‘with its ridiculous and<br />

miserly spirelet’ erected by ‘some ignorant<br />

and insensible architect in 1883’. Ignorance<br />

he deplored. <strong>The</strong> church at Stoven, ‘ a<br />

depressing neo-Norman job of 1849’, was an<br />

‘ignorant progeny’, and the spires of St John<br />

the Evangelist, Bury St Edmunds, and<br />

Westley, both by William Ranger, were<br />

likewise ‘ignorant’. <strong>The</strong> clock tower at<br />

Bildeston (1864) was simply ‘hideous’, as was<br />

that at Newmarket (1887) – ‘architecturally,<br />

Newmarket has very little to offer’. <strong>The</strong><br />

interior of the chancel at Stuston was ‘truly<br />

terrible’, Eye Town Hall (1857) ‘horrible . . .<br />

with a horrible tower’.<br />

It is interesting to know the views of<br />

someone who was soon to be chairman of<br />

the Victorian Society, who could also dismiss<br />

the interesting church at Boulge with ‘Early<br />

C16 brick tower. <strong>The</strong> rest seems all Victorian.’<br />

<strong>The</strong>n, ‘for the C20 in Suffolk one can be<br />

almost silent’. Of the ‘undeniably impressive’<br />

Royal Hospital School at Holbrook (1925–33)<br />

he wrote, ‘of originality, of a feeling that a<br />

completely new style in architecture was<br />

stirring, there is none’ (but the architects<br />

were consciously imitating the Royal Hospital<br />

at Greenwich); of the church at<br />

Chelmondiston, destroyed in the Second<br />

World War and rebuilt in 1957, ‘not an inkling<br />

of any development of architecture in the<br />

last sixty years’ (but the architect, Basil<br />

Hatcher, was perfectly capable of designing<br />

modern churches, and may well have<br />

thought that in a village setting a traditional<br />

Suffolk church was what was wanted). For<br />

Pevsner, the best buildings ‘belong literally<br />

to the last two or three years’. Time has<br />

certainly endorsed his enthusiasm for the<br />

new estate village at Rushbrooke, about half<br />

complete in 1961. Favourite local architects<br />

were Tayler & Green of Lowestoft and,<br />

especially, Johns, Slater & Haward of Ipswich<br />

– Pevsner includes an enthusiastic<br />

description of their Fison House in Ipswich,<br />

1959–60, based entirely on a photograph and<br />

information supplied by Birkin Haward.<br />

Later editions undoubtedly provide much<br />

more information, such as the identity of the<br />

architects of the Victorian buildings Pevsner<br />

so much disliked, and the first edition, even<br />

though it slips so much more easily into the<br />

coat pocket, is perhaps best kept for perusal<br />

at home; but it is still full of insight, and<br />

inspired description, that make it just as<br />

enjoyable and worth reading as it was in<br />

1961.<br />

Book Reviews start on page 24<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Architectural</strong> <strong>Historian</strong> <strong>Issue</strong> One / June 2015 13

FEATURE<br />

How the ‘King of<br />

Cornwall’ brought<br />

history to life<br />

Paul<br />

Holden assesses the legacy of Michael Trinick<br />

and the making of Trerice, near Newquay 1<br />

In 1953 George Edward Michael Trinick<br />

(1924–94) (Fig. 1) joined the National<br />

Trust in Cornwall as Assistant Agent. He<br />

rose steadily through the ranks becoming<br />

Area Agent in 1956, Regional Secretary of<br />

Devon and Cornwall in 1965 and Cornwall’s<br />

Regional Director between 1978 and 1984.<br />

Unusually during this time he simultaneously<br />

acted as Historic Buildings Representative, a<br />

curatorial role that saw him not only facilitate<br />

the acquisition of Trerice (Fig. 2), but also<br />

prepare it as a visitor attraction.<br />

Merlin Waterson, in his biography of Michael<br />

Trinick, concluded that he was ‘one of the<br />

most remarkable people ever to work for the<br />

National Trust’. 2 For many he was the selfproclaimed<br />

‘King of Cornwall’. Some thought<br />

him a ‘swashbuckler’, others a ‘cavalier’.<br />

James Lees Milne called him ‘a wonder of a<br />

man’ while Martin Drury described his<br />

methods as somewhat ‘unconventional’. 3 He<br />

was undoubtedly a workaholic and obsessive<br />

collector whose strong principles and<br />

determined character often rode-roughshod<br />

over convention. Behind his boisterous, yet<br />

softy spoken, public persona, his private<br />

correspondence reveals an intolerant, empire<br />

builder who glorified in elevated circles,<br />

counting amongst his friends John Betjeman,<br />

Daphne du Maurier, William Golding and<br />

members of the south-west gentry. 4<br />

His legacy remains one of profuse<br />

acquisition. Between 1953 and 1984 vast areas<br />

of coastline and many built properties were<br />

acquired throughout Devon and Cornwall. To<br />

encourage informed access he implemented<br />

Fig. 1 Michael Trinick, OBE (1924–94). © National<br />

Trust Images/Giles Clotworthy<br />

14 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Architectural</strong> <strong>Historian</strong> <strong>Issue</strong> One / June 2015

Fig. 2 East front of Trerice in c. 1818 by George Shepherd (c. 1782–c. 1830). © National Trust Images/<br />

John Hammond<br />

high standards of interpretation and<br />

established himself as a widely respected<br />

historian, writing many of the early house<br />

and coastal guides. 5 Another major focus was<br />

the presentation of the sites, his handwritten<br />

instructions issued on postcards became<br />

infamous and much feared.<br />

In a lecture given to the Attingham Trust in<br />

1993 Trinick explained his involvement in the<br />

purchase of the Elizabethan manor house<br />

and 14 acres of land.<br />

In 1953 there died in Devon a Mrs [Annie]<br />

Woodward, leaving to the Trust £30,000 …<br />

Whereas such bequests are normally spent on<br />

beautiful land the Trust decided, against<br />

precedent, to buy two houses, one in Devon<br />

[Dunsland] and one in Cornwall, modest<br />

enough in size to attract a tenant. [Trerice]<br />

came to the Trust empty but for the table in the<br />

hall which was too large to move, and it had to<br />

be furnished and opened to visitors from<br />

scratch. We found an excellent tenant, Mr Jack<br />

Elton, who was extremely generous in paying<br />

for the major repair of the house, and the<br />

rebuilding of the north wing . . . for some years<br />

only the hall and the Drawing room could be<br />

shown, and very little of the garden, for the<br />

tenants naturally wanted privacy . . . In the late<br />

60s we decided to show a greater part of the<br />

house and to restore the gardens [and<br />

outbuildings] . . . <strong>The</strong> house was largely<br />

unrecorded but, by pegging away at its history<br />

and development, the story became reasonably<br />

clear. It was the greatest fun to furnish it,<br />

gradually bringing together, at first from loans<br />

and then from gifts and purchases, suitable<br />

contents, increasingly those with some<br />

connection to the house. Indeed, I am afraid I<br />

was merciless in twisting the arms of people<br />

who I knew had things which had come from<br />

Trerice or had belonged to the Arundells. <strong>The</strong>re<br />

still remains in Wiltshire a cache of portraits of<br />

the Trerice Arundells. It is very rare that the<br />

Trust is able to start from scratch, for generally<br />

some furniture, and some portraits at least, are<br />

in the house when it is acquired. I think we<br />

more or less got it right for the place is<br />

outstandingly popular. Being modest in size,<br />

and with contents which are not grand, visitors<br />

feel they can relate to it. 6<br />

Without indigenous contents the story of<br />

Trerice lay in the buildings and the people<br />

who shaped them. In his 1954 guidebook<br />

Trinick considers the plasterwork some of the<br />

finest in the south-west and using his<br />

regional knowledge and architectural<br />

Fig. 3 Great Chamber overmantel, 1573. © National Trust Images/Nadia Mackenzie<br />

expertise he compared the ornate ceilings,<br />

the decorative 1572 overmantel in the Great<br />

Hall and the Fitzalan arms and Arundell<br />

heraldic overmantel in the Great Chamber<br />

with other provincial examples. However, as<br />

a storyteller he recognised that the everyday<br />

lives of servants was just as engaging as<br />

those of the elite and so made a feature of<br />

the Elizabethan plaster craftsman who, it<br />

would appear, ran out of space when adding<br />

the date to the Great Chamber overmantel,<br />

thus a number 3 can be seen on the end of<br />

the preceding Roman numerals (Fig. 3).<br />

By modern standards the guidebook was<br />

short and with hindsight hampered by a lack<br />

of documentary research. To be fair, when<br />

the house came to the Trust little was known<br />

about its early history other than that chapel<br />

licenses were granted in 1372 and 1413 and<br />

that the topographer John Norden referred<br />

fleetingly to the house being L-shaped. This<br />

earlier building was incorporated into a more<br />

fashionable east-facing E-shaped house<br />

between 1562, the year of Sir John Arundell’s<br />

(c. 1534–80) marriage, and 1572, the date<br />

inscribed on the Great Hall plasterwork.<br />

Likewise there was no investigation into the<br />

two enduring mysteries that surround the<br />

Elizabethan rebuild. <strong>The</strong> first is the Dutch<br />

gables, a unique feature in a county that has<br />

historically proved slow in adopting new<br />

architectural fashions. Hence, it is curious<br />

that an astylar house like Trerice boasts some<br />

of the earliest Dutch gables in England. Yet,<br />

there is no doubt that the Arundell family<br />

was progressive. Its members shunned the<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Architectural</strong> <strong>Historian</strong> <strong>Issue</strong> One / June 2015 15

Fig. 4 East front in c. 1920. <strong>The</strong> north range was demolished by a storm in the 1860s. ©National Trust<br />

Images/Trerice collections<br />

popular use of Cornish granite in favour of<br />

locally quarried silver grey elvan limestone<br />

and drew on a contemporary plan that<br />

perfectly displays the trend for privacy.<br />

This prompts the second question: why was<br />

an old-fashioned double-height Great Hall<br />

with minstrel’s gallery installed when such<br />

features were being phased out in favour of<br />

more private and intimate parlours and<br />

chambers?<br />

More recently our understanding of Trerice<br />

has advanced significantly. 7 Recent<br />

archaeology and building analysis has<br />

uncovered features such as a bowling green,<br />

a wilderness, orchard, kitchen Garden,<br />

ornamental terraces, a viewing mound and<br />

archery range of which documentary<br />

evidence tells us that the young ‘Master<br />

Robert . . . could shoot twelve score, with his<br />

right hand, and with his left, and from behind<br />

his head’. It has also been suggested that a<br />

Gatehouse once stood between the front of<br />

the house and what was described on a 1825<br />

estate map as a ‘Lady’s garden’.<br />

<strong>The</strong> story of the seventeenth century<br />

Arundells was one of lunacy, litigation,<br />

loyalty to the Crown and subsequent<br />

impoverishment which forced Sir John to<br />

petition Cromwell for help ‘quite ruinous’ he<br />

wrote ‘to my poor estate’. Fortunately the<br />

family was restored to favour at the<br />

Restoration. In 1698, after the death of the<br />

2nd Lord Arundell, a 27 room inventory was<br />

compiled which gives a good account of a<br />

neatly decorated prestigious house with<br />

modest furnishings. 8 Curiously the inventory<br />

describes 11 rooms assigned with a total of 14<br />

beds (not including seven beds that appear<br />

to be for servants), some situated in<br />

unexpected locations such as ‘the Roome<br />

within the Dining Roome’, ‘the Bowling<br />

Green Chamber’, three beds in the ‘Room<br />

within Clowance Chamber’, two in the<br />

‘Clowance Chamber’ itself and one in the<br />

kitchen and wash house. <strong>The</strong> obvious<br />

conclusion is that the house was not at the<br />

time the Arundells’ primary residence,<br />

perhaps just not fashionable enough when<br />

compared with their other house in St James<br />

Place in London.<br />

John Arundell (1701–68), the 4th Baron, did<br />

some small alterations to the house but had<br />

greater aspirations to create a new landscape<br />

park with ornamental walks, pleasure<br />

buildings, water features, lakes and islands<br />

said to be in a similar vein to the water<br />

gardens at Raglan Castle in South Wales. In<br />

1768 the estate passed through marriage to<br />

the Wentworth family and then in 1802, after<br />

several defaults of issue, passed to Sir<br />

Thomas Dyke Acland who used the house for<br />

agricultural storage. In 1820 it was said to be<br />

‘in a rapid state of decay’ the drawing room<br />

was according to Davies Gilbert ‘in a<br />

wretched, dilapidated state’ although<br />

F. W. L. Stockdale more optimistically wrote<br />

‘although going into decay, [Trerice] still<br />

displays much of its grandeur’.<br />

Acland restored the Great Hall and by 1859<br />

the house was shown to visitors despite the<br />

Great Chamber still being used as an ‘apple<br />

room’. 9 In c. 1860 the north range had fallen<br />

into much disrepair and a severe gale<br />

eventually tore down the perished fabric (Fig.<br />

4). He eventually sold up in 1915 and three<br />

years later Cornwall County Council<br />

purchased the estate in the name of the<br />

‘Homes for Heroes’ scheme whereby soldiers<br />

returning from the Great War were rewarded<br />

with agricultural land. In 1920 Trerice was<br />

sold again and after three further decades in<br />

private ownership, the property was<br />

acquired by the National Trust for £12,000<br />

from its then owner the author, politician,<br />

poet and country house restorer Somerset de<br />

Chair (Fig. 5). <strong>The</strong> auction of contents in<br />

September 1953 raised £4,000 and included a<br />

full length portrait of King Phillip IV of Spain<br />

sold for £300, a Naples seascape by Franz<br />

Catel sold for £125, a seventeenth century<br />

portrait of John Donne fetched £120, a<br />

triptych attributed to Johannes Mytens £110<br />

and a Sheraton commode fetched £250.<br />

Under the direction of the architect<br />

Christopher Corfield and financed to the<br />

tune of £48,000 by the new tenant J. F. Elton,<br />

who had made fortune out of Malaysian<br />

rubber, Trerice was restored between 1953<br />

and 1958. <strong>The</strong> main focus of this work was the<br />

rebuilding of the north range using the<br />

fragments found in the gardens (Fig. 6). <strong>The</strong><br />

house was reopened to visitors in 1964.<br />

Corfield, a keen pig farmer, encouraged his<br />

client to put some money into pig rearing<br />

and the barn was converted for this purpose.<br />

However, an outbreak of swine ’flu caused<br />

Elton a large financial loss and he had to<br />

leave the property.<br />

Fig. 5 1948 sale particulars from Country Life<br />

magazine. Author’s collection<br />

16 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Architectural</strong> <strong>Historian</strong> <strong>Issue</strong> One / June 2015

With more of the house available for visitor<br />

access Trinick's interpretive vision was to<br />

create a mythical family home appearing as if<br />

family members had just departed. His<br />

inspiration was how he imagined or<br />

remembered a small manor house between<br />

the wars when such houses were often found<br />

to be too expensive to maintain by their<br />

owners and were therefore let without<br />

contents.<br />

Of his methods Merlin Waterson wrote<br />

Today curotoriol eyebrows would be raised,<br />

partly because the circumstances in which<br />

Michoel worked would not be fully understood<br />

. . . Whot separates Michoel's opprooch from<br />

thot of todoy's curotors is that he sow himself<br />

as entitled to oct as the owner of o greot house<br />

might have done, discarding some things,<br />

ocquiring others, ond interested obove oll in<br />

what would bring history to life.'"<br />

For the presentation Trinick relied on<br />

generous bequests of good seventeenth and<br />

eighteenth century furniture and an<br />

exceptiona I collection of clocks and<br />

paintings, some from the collections of Mrs<br />

Ronald Greville of Polesden Lacey. To create<br />

a local interest two paintings by the<br />

eighteenth century Cornish artist John Opie<br />

were acquired, two more arriving in 1988<br />

from a bequest of his great friend the late<br />

Lady Mander of Wightwick.x His<br />

'unconsidered trifl es' or auction acquisitions<br />

were added to the mix,'lt was' he once said<br />

'like playing with a doll's house on a large<br />

scale'.':<br />

<strong>The</strong> measure of Trerice's success is that it has<br />

survived. <strong>The</strong> Trust's acquisition was inspired,<br />

after all, notwithstanding the Dutch gables, it<br />

remains quintessentially English. Trinick<br />

reinvented Trerice, as he did his other<br />

acquisitions, by capitalising on its regional<br />

distinctiveness and acknowledging new<br />

audiences created by the post-war consumer<br />

and tourist boom and fuelled by the<br />

popularity of 6os and 7os cultural heritage<br />

television programmes such as Going for a<br />

Song, Antiques Roodshow and Upstoirs<br />

Downstoirs. Some might argue that today its<br />

rich architectural legacy remains little<br />

understood beyond its confused arbitrary<br />

compendium of contents but Trerice's<br />

fortunes are typical of the way that the<br />

fortunes of country houses have ebbed and<br />

flowed over years. <strong>The</strong> house has survived<br />

civil war, debt, desperation, agricultural use,<br />

neglect, partial collapse, two world wars,<br />

wartime rehabilitation, excessive taxes, death<br />

duties, prospects of post-war abandonment<br />

and, during a time where country houses<br />

were demolished at an alarming rate,<br />

eventual loss.<br />

Fig.o'S

EXHIBITIONS<br />

Celebration of Britain’s<br />

glorious Georgian age<br />

CANALETTO’S ARCHITECTURE:<br />

CELEBRATING GEORGIAN<br />

BRITAIN<br />

<strong>The</strong> Holburne Museum, Bath<br />

27 June – 4 October 2015<br />

Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal<br />

22 October 2015 – 14 February 2016<br />

Sweeping skies, rippling waterways, and<br />

proud, elegant buildings ever-soslightly<br />

softened here and there by<br />

hazy sunlight: the ingredients of a typical<br />

work by Giovanni Antonio Canal invariably<br />

add up in the mind to form an image of<br />

Venice – but this new exhibition brings<br />

together for the first time the paintings<br />

produced by Canaletto in Britain.<br />

It was the best of British times in this<br />

Georgian age: trade was buoyant, buildings<br />

were sprouting along the London skyline,<br />

confidence was palpable; by contrast, on the<br />

Continent, the War of the Austrian<br />

Succession had dissuaded wealthy patrons<br />

from pursuing their respective Grand Tours,<br />

so in 1746 an enterprising Canaletto decided<br />

to come to booming Britain, where he lived<br />

and painted for nine years, resulting in a<br />

body of work that, particularly when viewed<br />

together, records a dynamic period in British<br />

social and architectural history.<br />

<strong>The</strong> touring exhibition, which began at<br />

Compton Verney in Warwickshire before<br />

travelling to the Holburne Museum in Bath<br />

and the Abbot Hall Art Gallery in Kendal,<br />

celebrates Britain and British architecture<br />

through the eyes of Canaletto in<br />

approximately 30 paintings, including A View<br />

of Greenwich from the River (c. 1750–52) and<br />

London: <strong>The</strong> Thames from Somerset House<br />

Terrace towards the City (1750–51).<br />

Although much of his British work depicts<br />

scenes of London and the River Thames,<br />

Canaletto also produced views of other sites<br />

18 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Architectural</strong> <strong>Historian</strong> <strong>Issue</strong> One / June 2015

facing page Canaletto (Giovanni Antonio Canal)<br />

1697–1768, A Self-Portrait with St Paul’s in the<br />

background at Anglesey Abbey, Cambridgeshire,<br />

© National Trust Images / Hamilton Kerr Inst/<br />

Chris Titmus<br />

left Canaletto (Giovanni Antonio Canal) 1697–1768, A<br />

View of Greenwich from the River, c. 1750–52, oil paint<br />

on canvas, © Tate, London 2014<br />

around the country, including Warwick<br />

Castle, Eton College, Badminton House and<br />

Alnwick Castle. It is appropriate, then, that<br />

the exhibition is to be housed in<br />

eighteenth-century buildings across England.<br />

Abbot Hall, for example, was built in the<br />

Palladian style just three years after<br />

Canaletto headed back to Italy. “For us, it is<br />

the perfect opportunity to celebrate our<br />

building as well as hosting the exhibition,”<br />

says Abbot Hall curator Beth Hughes. “It<br />

allows us to shine the light back on the<br />

building and on our collections.<br />

“For example, we have an nearcontemporary<br />

of Canaletto in George<br />

Romney, whose portrait work is often<br />

compared to Reynolds, but this gives visitors<br />

a chance to look at Romney’s work alongside<br />

another artist of his time.”<br />

<strong>The</strong> exhibition offers a satisfying variety of<br />

scale, from large paintings to more intimate<br />

pieces. Visitors will also be glad to see<br />

London: Interior of the Rotunda at Ranelagh<br />

(c. 1754) portraying a rococo interior that sits<br />

in stark contrast to the trademark picture<br />

postcard vistas. Kay Carson<br />

below Canaletto (Giovanni Antonio Canal) 1697–1768, London: <strong>The</strong> Thames from Somerset House Terrace towards<br />

the City, Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2014<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Architectural</strong> <strong>Historian</strong> <strong>Issue</strong> One / June 2015 19

Reading between the<br />

lines of Mackintosh<br />

design<br />

MACKINTOSH ARCHITECTURE<br />

<strong>The</strong> Architecture Gallery, RIBA, London<br />

Charles Rennie Mackintosh has been<br />

described in turn as a proponent of<br />

art nouveau, symbolism, modernism,<br />

and much more. I should regard that as not<br />

so much confusing, but complimentary, to<br />

this architect, artist and designer that a great<br />

many movements and periods want to claim<br />

at least a part of him as their very own.<br />

Mackintosh Architecture, hosted at the RIBA in<br />

the spring after a spell in its native Hunterian<br />

Art Gallery at the University of Glasgow, was<br />

described as ‘the first substantial exhibition<br />

to be devoted to his architecture’ and it lived<br />

up to the brief. With more than 60 original<br />

drawings and watercolours, interspersed by<br />

models, the show offered a tasteful and<br />

considered insight into the developing mind<br />

and talents of Mackintosh from apprentice<br />

draughtsman at Honeyman and Keppie,<br />

through to fully-fledged architect, and<br />

partner at the practice. <strong>The</strong>re was something<br />

refreshing about being permitted to examine<br />

his architectural drawings purely in that<br />

context – Mackintosh as architect – without<br />

reference to the iconic motifs endlessly<br />

recreated, copied, and reproduced in a way<br />

that for some has risked diluting his legacy,<br />

in Benjaminian fashion.<br />

In addition to drawings of his most wellknown<br />

buildings, such as the Glasgow School<br />

20 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Architectural</strong> <strong>Historian</strong> <strong>Issue</strong> One / June 2015

Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1893) by James Craig<br />

Annan, © T&R Annan, courtesy<br />

GlasgowMackintosh.com<br />

below Artist’s House in the Country by Charles Rennie<br />

Mackintosh © Hunterian, University of Glasgow<br />

Design for Scotland Street School (1904) by Charles<br />

Rennie Mackintosh © Hunterian, University of<br />

Glasgow<br />

of Art, the Glasgow Herald building (now <strong>The</strong><br />

Lighthouse), and Scotland Street School, the<br />

exhibition also revealed details of unbuilt<br />

works, including two rejected competition<br />

entries – one for the Glasgow International<br />

Exhibition of 1901, and an extraordinary<br />

vision for Liverpool Cathedral that did not<br />

even make the shortlist in the 1901–03<br />

cathedral project (eventually won by Giles<br />

Gilbert Scott). Regardless of whether the<br />

projects made it into sandstone, or brick, the<br />

joy of this exhibition was to experience up<br />

close the original ink designs of an<br />

architectural giant.<br />

Mackintosh Architecture was the culmination<br />

of a four-year AHRC-funded research project<br />

led by <strong>The</strong> Hunterian Art Gallery, ‘Mackintosh<br />

Architecture: Context, Making and Meaning’,<br />

www.mackintosh-architecture.gla.ac.uk.<br />

<strong>The</strong> RIBA exhibition was supported by the<br />

Monument Trust and RIBA Patrons.<br />

Kay Carson<br />

Coming up…<br />

NATIONAL TASTE: PALLADIO<br />

AND BRITISH PALLADIANISM<br />

RIBA, London<br />

1 September to 31 October, 2015<br />

Following soon after the SAHGB’s own<br />

symposium held in May to mark the<br />

tercentenary of the publication of Vitruvius<br />

Britannicus, a new exhibition is to open at the<br />

RIBA in September, designed to celebrate<br />

and explore the development of British<br />

classicism in the period 1715 to 1815.<br />

National Taste: Palladio and British<br />

Palladianism will feature drawings, models<br />

and photographs from the collections at<br />

RIBA and elsewhere to examine the origins<br />

and key figures behind an enormously<br />

influential style that can be seen in a wide<br />

variety of UK buildings and landmarks.<br />

A report and pictures from the SAHGB’s<br />

2015 Symposium – ‘<strong>The</strong> Tercentenary of<br />

Vitruvius Britannicus: <strong>Architectural</strong> Books in<br />

Eighteenth Century Britain’ – is due to be<br />

published in <strong>Issue</strong> 2 of <strong>The</strong> <strong>Architectural</strong><br />

<strong>Historian</strong>.<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Architectural</strong> <strong>Historian</strong> <strong>Issue</strong> One / June 2015 21

Meeting of minds at<br />

the Old College<br />

Forum attendees listening to the <strong>Architectural</strong> History<br />

Beyond Academia discussion (top table, from left) Alex<br />

Bremner, Chris Miele, Olivia Horsfall Turner and<br />

Kathryn Ferry<br />

Braving the Edinburgh elements for an architectural<br />

tour of the city<br />

<strong>The</strong> GRSF Organising Committee (from left) Andrew<br />

Horn, Íñigo Basarrate, Emily Turner and Laura Bowie<br />

<strong>The</strong> SAHGB 3rd Annual Graduate<br />

Student Research Forum was held in<br />

the inspiring surroundings of the<br />

Playfair Library at the University of Edinburgh<br />

on a sunny Saturday in April. <strong>The</strong> first session<br />

of student papers began with a discussion of<br />

the architectural development of Sedilia in<br />

English churches by James Cameron<br />

(Courtauld Institute of Art), followed by<br />

insights into the wider function of early<br />

modern urban defences beyond the<br />

defensive by Simon Webb (University of<br />

York), concluding with Arthur Trieu<br />

(University of Cambridge) on the significance<br />

of timber-framed structures in the<br />

earthquake-prone Italian city of L’Aquila.<br />

Post-coffee, Julian Holder (University of<br />

Salford) moderated a discussion on Writing<br />

about Architecture: Rights and Responsibilities,<br />

accompanied by Richard Anderson<br />

(University of Edinburgh), Timothy Brittain-<br />

Catlin (Kent School of Architecture), and<br />

Hannah Malone (University of Cambridge).<br />

Concepts of the role of the architectural<br />

historian were discussed which highlighted<br />

the importance of thinking outside of the<br />

academic arena and more broadly about the<br />

mechanisms that created a particular<br />

building or architectural style. <strong>The</strong><br />

selectiveness of the historical canon was also<br />

addressed as well as the function of the<br />

university as a tool to show students where<br />

to find stories rather than to dictate them.<br />

This was followed by the second session of<br />

student papers. Sydney Ayers (University of<br />

Edinburgh) began with insights into the early<br />

work of Robert Adam and the business of<br />

architecture; Laura di Zerega (University of<br />

California) followed with a discussion of<br />

Schinkel’s influence on the ecclesiastical<br />

architecture of the Rhineland. Danai<br />

Konstantinidou (Cyprus Institute) concluded<br />

the session with a history of the British<br />

Empire’s role in the development of the<br />

harbour of Famagusta.<br />

After lunch, session three started with<br />

Claudio Leoni (Bartlett School of<br />

Architecture) and a discussion of Semper’s<br />

attitude to towards the Crystal Palace as a<br />

means of addressing both capitalism and<br />

anthropology. Dimitri de Preux (University<br />

College London) spoke on the historical<br />

eclecticism of the Samsung Building in Los<br />

Angeles and the appropriation of style for<br />

differing functions. Bente Ass Solbakken<br />

(University of Oslo) concluded the session<br />

with an analysis of the relationship between<br />

the assimilation of architecture from other<br />

countries and the development of a national<br />

Norwegian style.<br />

<strong>The</strong> second roundtable discussion on<br />

Alternatives to Academia: Heritage/<br />

Conservation/ Curatorship was moderated by<br />

Alex Bremner (University of Edinburgh)<br />

accompanied by Chris Miele (Montagu<br />

Evans), Olivia Horsfall Turner (V&A Museum),<br />

and Kathryn Ferry (freelance writer and<br />

scholar). <strong>The</strong> opportunities in both public<br />

and private sectors were discussed with the<br />

importance of cultivating a broad range of<br />

interests during post-graduate studies<br />

highlighted as a key way to open up avenues<br />

that might not otherwise be immediately<br />

apparent.<br />

After coffee, the final student papers were<br />

presented, beginning with Horatio Joyce<br />

(University of Oxford) and his analysis of the<br />

architectural importance of clubs in<br />

late-nineteenth century New York. Tim Fox-<br />

Godden (University of Kent) then spoke on<br />

the memorialisation of wartime landscapes<br />

in the cemeteries of the Western Front; Leah<br />

Xiao (University of York) concluded the<br />

student papers with a discussion of<br />

I. M. Pei’s Museum for Chinese Art and the<br />

convergence of modernism with traditional<br />

Chinese motifs.<br />

<strong>The</strong> keynote speech was delivered by the<br />

ever-engaging Professor Iain Boyd Whyte<br />

(University of Edinburgh) on the subject of<br />

<strong>The</strong> Architect as Author.<br />

<strong>The</strong> day provided ripe ground for further<br />

conversations over wine within the<br />

spectacular architectural setting of Old<br />

College and was followed by some muchneeded<br />

sustenance.<br />

Sunday morning dawned wet and windy for<br />

an architectural tour of Edinburgh led by<br />

Margaret Stewart (University of Edinburgh).<br />

An ensemble of brave attendees made their<br />

way through the narrow streets and closes of<br />

the old town before finding themselves in<br />

the rational spaces of the new town. <strong>The</strong> sun<br />

finally made an appearance as the tour<br />

culminated in the shadow of Calton Hill, the<br />

symbol of education prowess within the city:<br />

a fitting end for an intellectually stimulating<br />

weekend.<br />

Laura Bowie<br />

On behalf of the GSRF Organising Committee<br />

Iñigo Basarrate, Laura Bowie, Andrew Horn,<br />

Emily Turner<br />

22 <strong>The</strong> <strong>Architectural</strong> <strong>Historian</strong> <strong>Issue</strong> One / June 2015

A week in the life…<br />

. . . of Dr James Campbell, Fellow in<br />

Architecture and History of Art at<br />

Queens’ College Cambridge. His<br />

books include Brick (Thames<br />

and Hudson, 2003), Building<br />

St Paul’s (Thames and Hudson,<br />

2007), <strong>The</strong> Library: a World<br />

History (Thames and Hudson,<br />

2013) and <strong>The</strong> Staircase<br />

(Routledge, 2014).<br />

Iremember as an architecture student<br />

writing to Sir Howard Colvin and being<br />

surprised to be invited to his house in<br />

Oxford for tea. I went along and sat nervously<br />

in his living room, in awe of this<br />

extraordinarily generous and by then rather<br />

ancient academic. He listened carefully to<br />

what I had to say, politely correcting things<br />

here and there, and patiently directing me to<br />

sources I should look at. It was a master class<br />

in supervision, and also in academic<br />

generosity.<br />

I do not see my students at home (my house<br />

is not exactly round the corner from college<br />

as Colvin’s was), but I do serve tea. Sir<br />

Howard’s copy of the Wren Society, which I<br />

purchased at auction after his death, now sits<br />

in the corner of the room. Full of his scribbled<br />

notes, it is a treasured possession. My college<br />

room has white bookcases up to dado height<br />

covering all those spaces not taken up with<br />

window seats, doors and the fireplace. Above<br />

the bookcases, the walls are painted deep<br />

green and covered in engravings. <strong>The</strong><br />

sloping floor and exposed timber framing are<br />

the few clues that reveal the room’s<br />

seventeenth-century origin. <strong>The</strong> windows<br />

look out over the court towards the walnut<br />

tree and the President’s Garden. This room is<br />

where I write and I supervise. I glance<br />

occasionally across the court at Bodley’s<br />

glorious Chapel (1886) or Basil Spence’s<br />

elegant Erasmus building (1959), both of<br />

which I can see from my chair.<br />

My day does not start in this room. It begins<br />

by dropping my son at school and cycling to<br />

the Faculty from the station. More often than<br />

not there is then a meeting to attend. <strong>The</strong> life<br />

of an academic architectural historian would<br />

be complete bliss if it involved nothing more<br />

than teaching, researching and writing. Of<br />

course it doesn’t: it involves a great deal of<br />

meetings. I counted a few years ago that I<br />

was sitting on fifty committees of one sort or<br />

another. I have done my best to whittle it<br />

down and I think I have currently reduced it<br />

to about thirty. Term time is seemingly<br />

endless committee meetings, followed by<br />

the tedious administrative tasks that come<br />

out of them. Of course you cannot attend<br />

them all, because they clash with each other,<br />

with lectures and with supervisions, but sadly<br />

they cannot be avoided altogether.<br />

I glance occasionally across the<br />

“<br />

court at Bodley’s glorious Chapel<br />

or Basil Spence’s elegant Erasmus<br />

building, both of which I can see<br />

from my chair.<br />

”<br />

After meetings come lectures. It is probably<br />

unfashionable to say so, but I enjoy lecturing.<br />

My lectures come just before lunch. Slide<br />

show over, I leave the Faculty, jump on the<br />

bike and head for college, which is just a<br />

short cycle ride away, past the Fitzwilliam<br />

Museum (Basevi/Cockerell, 1848) and the Pitt<br />

Building (Blore, 1832). My bicycle is leant<br />

against the front walls of the college beside<br />

the gate. I used to have a mountain bike,<br />

which was given to me and I rode for many<br />

years, but it recently fell apart. Its<br />

replacement is a heavy black upright Dutch<br />

bike with a rectangular covered basket on a<br />

rack on the front. <strong>The</strong> weight gives me<br />

exercise, while the basket is invaluable when<br />

you have books to carry. <strong>The</strong>re are always<br />

books to carry.<br />

After dropping my rucksack and coat in my<br />

college room on the old side of college, I pass<br />

through the cloister beneath the President’s<br />

Lodge (a pretty 16th-century architectural<br />

enigma) and cross over the famous<br />

mathematical bridge (William Etheridge,<br />

1749). If it’s raining (and if it is winter it<br />

probably will be), I run for the cloister under<br />

Powell and Moya’s Cripps Building (1976). A<br />

compromised design, this has never been my<br />

favourite building in Cambridge. I prefer the<br />

St John’s one, which has had its own share of<br />

problems, but meets the water so beautifully<br />

and is so much more castle-like. I have been<br />

organising a catalogue of the college’s<br />

drawings and I recently discovered the first<br />

proposal was similar to the St John’s<br />

building. Sadly that scheme was rejected<br />

early on. One thing you cannot fault about<br />

the one that was built is the quality of the<br />

materials: the panelling in the hall is<br />

beautifully done. Lunch quickly eaten, there<br />

is time to catch up on college gossip before<br />

the students start arriving for the first<br />

supervision at 2 pm.<br />

Supervisions are done in college. We sit<br />

around a large mahogany table if it is a group<br />

of 2–3, or in armchairs in front of the fire if it is<br />

a 1:1. <strong>The</strong>y last an hour each and I serve tea<br />

and biscuits to keep us all going. I hope<br />

Howard would have approved. Supervisions<br />

start at 2 pm and finish at 6 pm when I go to<br />

the college cafeteria and wolf down supper<br />

before grabbing the bicycle and heading<br />

back to the station. Terms are short and<br />

intense, leaving little time for research<br />

between the meetings, lectures and<br />

supervisions. Once the students disappear<br />

and the reports are written up, there is finally<br />

time to get down to those tasks that have<br />

lain dormant for 8 weeks. Picking up the<br />

threads again is always difficult, and there is<br />

never enough time to spend in the libraries<br />

or archives as one would wish, but in some<br />

ways that makes you value it more when you<br />

do. Even in a place where most people think<br />

time stands still, there never seems to be<br />

enough of it<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Architectural</strong> <strong>Historian</strong> <strong>Issue</strong> One / June 2015 23

BOOK REVIEWS<br />

ERIC FERNIE: Romanesque Architecture: <strong>The</strong> First Style of<br />

the European Age (Yale University Press, 2014, 300 pp.,<br />

388 col. and b&w illus. plus two maps, £55.00, ISBN:<br />

9780300293547)<br />

This is an old-fashioned book and that is<br />

most welcome. <strong>The</strong> text is divided into four<br />