GEORGE HUTCHINSON

orxwju5

orxwju5

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

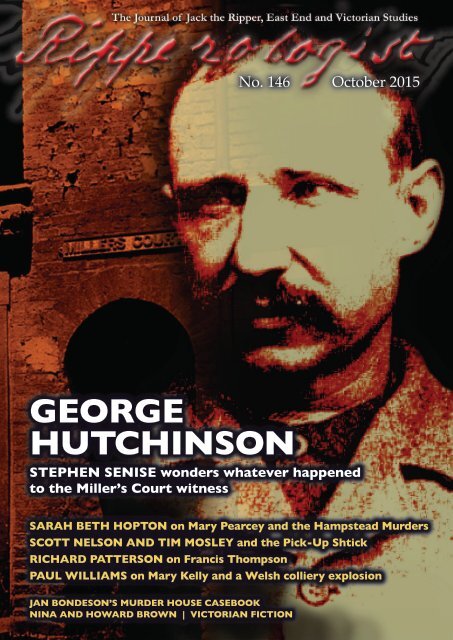

No. 146 October 2015<br />

<strong>GEORGE</strong><br />

<strong>HUTCHINSON</strong><br />

STEPHEN SENISE wonders whatever happened<br />

to the Miller’s Court witness<br />

SARAH BETH HOPTON on Mary Pearcey and the Hampstead Murders<br />

SCOTT NELSON AND TIM MOSLEY and the Pick-Up Shtick<br />

RICHARD PATTERSON on Francis Thompson<br />

PAUL WILLIAMS on Mary Kelly and a Welsh colliery explosion<br />

JAN BONDESON’S MURDER HOUSE CASEBOOK<br />

NINA AND HOWARD BROWN | VICTORIAN FICTION<br />

Ripperologist 118 January 2011 1

Quote for the month<br />

“I’ll put my cards on the table and say we definitely did make contact with<br />

Jack the Ripper. I felt there was a tall gentleman looking very dark and<br />

mysterious, very much like him. [The London Dingeon has] an area dedicated to<br />

Jack the Ripper and I feel that could attract him as a spirit.”<br />

TV psychic Ian Lawman wins this year’s Halloween quote with his description of Jack the Tourist. The Daily Star, 28 October 2015<br />

Ripperologist 146<br />

October 2015<br />

EDITORIAL: ‘UNFORTUNATES’ AND BÊTES NOIRS<br />

by Christopher T George<br />

TERROR AUSTRALIS: WHATEVER HAPPENED TO<br />

<strong>GEORGE</strong> <strong>HUTCHINSON</strong>?<br />

by Stephen Senise<br />

AN UNGOVERNED PASSION:<br />

JOURNALISTIC CONSTRUCTIONS OF MARY PEARCEY<br />

AND THE HAMPSTEAD TRAGEDY<br />

by Sarah Beth Hopton<br />

THE PICK-UP SHTICK<br />

by Scott Nelson and Walter Mosley<br />

THE HOUND OF DEATH: FRANCIS THOMPSON<br />

AND THE WHITECHAPEL MURDERS<br />

by Richard Patterson<br />

DEATH IN THE COLLIERY<br />

by Paul Williams<br />

FROM THE CASEBOOKS OF A MURDER HOUSE DETECTIVE<br />

by Jan Bondeson<br />

A FATAL AFFINITY: CHAPTER FOUR<br />

Nina and Howard Brown<br />

DEAR RIP<br />

Your letters and comments<br />

VICTORIAN FICTION:<br />

THE THRONE OF THE THOUSAND TERRORS<br />

by William Le Queux<br />

REVIEWS They All Love Jack and more!<br />

EXECUTIVE EDITOR<br />

Adam Wood<br />

EDITORS<br />

Gareth Williams<br />

Eduardo Zinna<br />

REVIEWS EDITOR<br />

Paul Begg<br />

EDITOR-AT-LARGE<br />

Christopher T George<br />

COLUMNISTS<br />

Nina and Howard Brown<br />

David Green<br />

The Gentle Author<br />

ARTWORK<br />

Adam Wood<br />

Follow the latest news at<br />

www.facebook.com/ripperologist<br />

Ripperologist magazine is free of<br />

charge. To be added to the mailing list,<br />

send an email to contact@ripperologist.<br />

biz.<br />

Back issues form 62-144 are<br />

available in PDF format: ask at<br />

contact@ripperologist.biz<br />

To contribute an article, please email<br />

us at contact@ripperologist.biz<br />

Contact us for advertising rates.<br />

www.ripperologist.biz<br />

COVER IMAGE: We would like to acknowledge the valuable assistance given by the following people in the production of this issue of Ripperologist: Rob Gallop, Loretta<br />

Lay and Mark Ripper. Thank you!<br />

Ripperologist is published by Mango Books. The views, conclusions and opinions expressed in signed articles, essays, letters and other items published in Ripperologist<br />

are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, conclusions and opinions of Ripperologist, its editors or the publisher. The views, conclusions and<br />

opinions expressed in unsigned articles, essays, news reports, reviews and other items published in Ripperologist are the responsibility of Ripperologist and its<br />

editorial team, but do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the publisher.<br />

We occasionally use material we believe has been placed in the public domain. It is not always possible to identify and contact the copyright holder; if you claim<br />

ownership of something we have published we will be pleased to make a proper acknowledgement.<br />

The contents of Ripperologist No. 146, October 2015, including the compilation of all materials and the unsigned articles, essays, news reports, reviews and other<br />

items are copyright © 2015 Ripperologist/Mango Books. The authors of signed articles, essays, letters, news reports, reviews and other items retain the copyright of<br />

their respective contributions. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted or otherwise circulated<br />

in any form or by any means, including digital, electronic, printed, mechanical, photocopying, recording or any other, without the prior permission in writing of<br />

Ripperologist. The unauthorised reproduction or circulation of this publication or any part thereof, whether for monetary gain or not, is strictly prohibited and may<br />

Ripperologist 118 January 2011 2<br />

constitute copyright infringement as defined in domestic laws and international agreements and give rise to civil liability and criminal prosecution.

‘Unfortunates’<br />

and Bêtes Noirs<br />

EDITORIAL by CHRISTOPHER T <strong>GEORGE</strong><br />

Although the broad and well-known stories of the ‘Unfortunates’ who were Jack the Ripper’s<br />

victims have remained much the same for the past 127 years, the face of ‘Jack’ himself continues<br />

to change, with an endless parade of newly promoted or revived suspects. No doubt to the utter<br />

confusion or else fascination of the public - or is it more boredom with the topic by this point?<br />

Well, frankly, the way the media jumps on each new sensational theory, with little discernment as<br />

to the particular theory’s possible flaws or shortfalls, it seems newspaper writers and editors and<br />

TV producers have the sense that members of the public retain their hunger for news of ‘Jack’<br />

and the latest narrative that will forever settle the never-ending question of who he (or she) was.<br />

Somehow it’s still the bloody autumn of 1888 and everyone is panting waiting to know the identity<br />

of the unknown killer.<br />

When my wife Donna and I attended the Salisbury Conference in September<br />

2014, the ‘big thing’ was Russell Edwards’ recently published book, Naming<br />

Jack the Ripper, and he and his Liverpool John Moores University DNA expert,<br />

Dr Jari Louhelainen, were in attendance to tell the delegates that indeed<br />

the shawl allegedly found in Mitre Square on the night of 30 September<br />

1888 contained DNA from the blood of victim Catherine Eddowes and the<br />

semen of suspect Aaron Kosminski - or at least that the DNA would match<br />

that of modern-day relatives of both parties. Doubts about these revelations<br />

have since arisen, to the extent that the DNA matches are believed by<br />

many observers to be not as rare or as strong as Mr Edwards continues to<br />

aver. Meanwhile, out in the lobby of the Mercure White Hart Hotel, was the<br />

manuscript of the alleged confession of one James Carnac who claimed to<br />

have been the Ripper, also published in the months before the convention. A<br />

piece of fiction no doubt but also with its own claims to a corner in the rich<br />

and somewhat confusing story of the Whitechapel murders from 1888 to the<br />

modern day. A long and winding road with no end.<br />

Russell Edwards and the alleged Eddowes shawl<br />

Mr Edwards and the shawl also figured prominently in a segment of ‘CBS<br />

Sunday Morning’ that aired here in the United States this past Sunday, 25<br />

October. I had fully expected to be treated to the spectacle of learning<br />

that the Ripper is revealed to be celebrity musician and baritone Stephen<br />

Adams, aka Liverpool-born Michael Maybrick, but it seems that the CBS<br />

story was prepared for Halloween before Bruce Robinson’s They All Love<br />

Jack: Busting the Ripper, implicating Maybrick, hit the bookshops, and the<br />

producers received insufficient ‘heads up’ to enable them to jump on to the<br />

‘next big thing’ - the absolutely latest revelation about the Ripper. Friends,<br />

is this story starting to become a bit tawdry - can we somehow get off this<br />

neverending ghoulish cavalcade? Would the media perhaps help us to look at<br />

the situation a bit more rationally? Or might that be making too frank a call<br />

to the honest, news-reporter souls in the media?<br />

Ripperologist 146 October 2015 1

And what of Bruce Robinson and his theory? A Hollywood scriptwriter,<br />

acclaimed for the movies The Killing Fields and Withnail and I, has suddenly<br />

become an ‘expert’ on the Whitechapel murders with a book fifteen years in the<br />

making. But unfortunately, as with American crime novelist Patricia Cornwell,<br />

author of Portrait of a Killer: Jack the Ripper - Case Closed nearly 15 years ago,<br />

who sought to skewer as the Ripper British expressionist artist Walter Sickert,<br />

a celebrity that she clearly detests, Mr Robinson similarly seeks to pillory a<br />

man he hates, Michael Maybrick, as the guy who slaughtered prostitutes in<br />

Whitechapel. But on what evidence? The scriptwriter’s statements about his<br />

chosen suspect even before the October publication of his book did not bode<br />

well. As reported in an article by Richard Inman in The Independent on 31 May<br />

2015, Robinson declared, ‘He was a prick - a psychopathic prick. Somehow<br />

he’s managed to accrue this almost heroic aura, but I have no time for that. I<br />

go after the bastard.’ 1 In an interview on Soundcloud, the scriptwriter doubles<br />

down on this characterization and admits he is a cynic in approaching the<br />

case, as he is about most things. That seems about true in that throughout his<br />

long, long book, he lambastes in turn earlier writers on the case along with<br />

Scotland Yard officials, and of course his chosen suspect, the composer of the<br />

popular period song, ‘They All Love Jack,’ as well as of well-known hymns<br />

such as ‘The Holy City’ 2 written with the composer’s longtime collaborator,<br />

lyricist Frederic Weatherly. Indeed, Robinson proudly asserts in the Soundcloud<br />

interview, ‘This book is a repudiation of virtually everything that Ripperology<br />

has ever written!’ 3<br />

For all the voluminous pages of his book, stuffed with ‘new’ research and<br />

analysis, Mr Robinson gets a lot wrong. For example, he characterizes suspect<br />

Aaron Kosminski as a weakling who couldn’t possibly have committed the<br />

murders. But he appears to have based his ideas on Kosminski’s weakened<br />

physical shape on the medical data collected about the man while he was<br />

in Colney Hatch Asylum. Information in other words describing the Polish<br />

Jew’s physique in his last months before he died in 1919 rather than the<br />

man’s physical shape in his prime in 1888 - indeed Robinson characterizes<br />

Kosminski as if the information about the weak nature of the man was known<br />

by Scotland Yard in 1888, which makes little sense given Sir Robert Anderson’s<br />

later adamant claim that the Jew was the Ripper. Would Anderson have named<br />

a man who would have been physically incapable of committing the crimes?<br />

Similarly, for some reason Robinson claims that after the Maybrick trial - the<br />

murder trial in Liverpool in which Michael Maybrick’s American-born sister-inlaw<br />

Florence Maybrick, was convicted for the poisoning death by arsenic of his<br />

brother, cotton merchant James Maybrick, for which Florence served 15 years<br />

in gaol, Michael Maybrick became a recluse on Isle of Wight. Totally untrue!<br />

Maybrick was elected five times as Mayor of Ryde, served as a justice of the peace, became president of the Isle of Wight<br />

Conservative Association and chairman of the county hospital. He even represented Ryde at the coronations of Edward<br />

VII (9 August 1902) and George V (22 June 1911), before finally dying in Buxton, Derbyshire, on 25 August 1913. 4 The man<br />

could not have led a more public life.<br />

Top: Bruce Robinson, author of<br />

They All Love Jack: Busting the Ripper<br />

Bottom: ‘They All Love Jack’ by F E Weatherly<br />

and Stephen Adams (aka Michael Maybrick)<br />

Period songsheet<br />

1 Richard Inman, ‘Bruce Robinson: Creator of Withnail and I on his new book about Jack the Ripper,’ The Independent, 31 May 2015.<br />

2 Frank Patterson sings ‘The Holy City.’ Released on the 1996 album, ‘Amazing Grace’. Written by Stephen Adams (Michael Maybrick)<br />

and Frederic Weatherly in 1892.<br />

3 4th Estate Books: 4 Books, Interview with Bruce Robinson at soundcloud.com/4thestate-1/4-books-bruce-robinson<br />

4 ‘Death of Mr Michael Maybrick, JP. The Great Vocalist and Composer Dies in His Sleep. Ryde and the Island’s Loss.’ Isle of Wight<br />

County Press, Saturday, 30 August 1913.<br />

Ripperologist 146 October 2015 2

Robinson also insinuates darkly that, before<br />

the East End crimes of the Ripper, while on a<br />

singing tour of the United States, Maybrick,<br />

a heart-throbbingly mellifluous baritone and<br />

apparently, according to this writer, also a<br />

globe-trotting serial killer, committed the<br />

famous Ripper-like series of ‘servant girl<br />

murders’ in Austin, Texas - the bloody murders<br />

of eight African-American servant girls. Once<br />

again this is erroneous and loose thinking. It is<br />

well recorded that Maybrick toured the United<br />

States and Canada in 1884, but the servant girl<br />

murders occurred mostly in 1885, seven in all<br />

in that year, with only one of the crimes, the<br />

first, occurring in 1884 the year of the tour -<br />

the murder of Mollie Smith, on 30 December<br />

1884. 5 During the Texan crime spree, therefore,<br />

Michael Maybrick was back in Britain and can<br />

safely be exonerated of those crimes!<br />

Getting back to my original mention of<br />

‘Unfortunates’ - yes the downtrodden women<br />

of Whitechapel, Spitalfields and St Georgein-the-East<br />

who were the victims of Jack the<br />

Ripper, are rightly called ‘unfortunates.’ But<br />

perhaps, might I say, perversely, a large number<br />

of men who have been named as suspects by<br />

now, wrongly, are also unfortunates in a real<br />

sense as well!<br />

Michael Maybrick aka composer Stephen Adams, 1907. Courtesy of Rob Gallop.<br />

5 Michael Corcoran, ‘Rediscovering Austin’s Jack the Ripper’ available at www.casebook.org/dissertations/dst-austin.html.<br />

WRITE FOR RIPPEROLOGIST!<br />

We welcome contributions on Jack the Ripper, the East End and the Victorian era.<br />

Send your articles, letters and comments to contact@ripperologist.biz<br />

Ripperologist 146 October 2015 3

Terror Australis:<br />

Whatever Happened to<br />

George Hutchinson?<br />

By STEPHEN SENISE<br />

Having wandered into Commercial Street police station voluntarily at the height of London’s<br />

Ripper scare in November 1888, George Hutchinson, possibly the case’s most enigmatic witness,<br />

seems to have vanished from the face of the earth not long thereafter.<br />

Ripperologists have spent many decades diving into mouldy archives, scouring yellowing newspaper articles,<br />

and been left scratching their heads. Post-contemporary reports pick up a possible trail many years after events,<br />

usually involving a photo, purportedly the first ever located of this elusive witness, and to this day the only one<br />

ever presented. The picture came to attention in tandem with statements by son, Reginald, attributed to father<br />

George, implying a royal-masonic conspiracy at the root of the Ripper saga.<br />

Most were unconvinced by such testimony, framed as it was by in-vogue theories assuaging the collective<br />

imagination during those years courtesy of Stephen Knight’s Jack The Ripper: The Final Solution and later Melvyn<br />

Fairclough’s The Ripper and The Royals, in which Reginald quotes George saying: “It was more to do with the Royal<br />

Family than ordinary people.”<br />

Reginald’s father, full name, George William Topping Hutchinson, was born in 1866. Accomplished violinist in<br />

his spare time, rarely out of work plumber by trade, he was possibly too young at 22 to be the underemployed 1<br />

witness who in 1888 was sleeping in a doss house and who only ever appeared in contemporary police and media<br />

reports as plain old George Hutchinson. Where modern literature 2 ventures an opinion, it puts the police witness<br />

at about 28 years of age at the time, though the question remains open.<br />

In 1993, document examiner Sue Iremonger opined that the signature of George William Topping Hutchinson was<br />

not the same as George Hutchinson’s when compared to the latter’s, as appears on his police witness statement<br />

of 1888. But she allowed for the possibility that the ten year gap between the production of the two might have<br />

accounted for such a marked difference.<br />

Irrespective, the witness who in 1888 claimed to have got such a good look at the Ripper that he knew the<br />

colour of his eyelashes was about to get a promotion. Thanks to a quick succession of works by Bob Hinton, From<br />

Hell: The Jack the Ripper Mystery (1998), Stephen Wright, Jack the Ripper: An American View (1999), John<br />

Eddleston, Jack The Ripper: An Encyclopedia (2001), Garry Wroe, Jack the Ripper: Person or Persons Unknown<br />

(2002), and Chris Miles, On the Trail of a Dead Man: The Identity of Jack the Ripper (2004), George Hutchinson<br />

went from witness to suspect, all within the span of the same decade in which his purported photo had appeared.<br />

Without landing the knockout blow, the authors presented a robust case, for all the limitations posed chasing<br />

the suspect in a murder spree of whom all trace had long vanished.<br />

During the long span of time that George Hutchinson’s Ripper candidacy had gone unnoticed the art of criminal<br />

profiling had evolved and become a sophisticated tool the likes of which the cases’s lead detective Frederick<br />

Abberline and nineteenth century colleagues could only have dreamed of.<br />

1 The term unemployed was used in an earlier version of this article – see other examples for its usage re Hutchinson: The Whitechapel<br />

Society, Jack the Ripper: The Suspects (2013); Maxim Jakubowski, The Mammoth Book of Jack the Ripper (2008); John Douglas &<br />

Mark Olshaker, The Cases That Haunt Us (2000); Christopher J Morley, Jack the Ripper: A Suspect Guide (2005).<br />

2 For example, Bob Hinton, From Hell: The Jack the Ripper Mystery (1998); Garry Wroe, Jack the Ripper: Person or Persons Unknown<br />

(2002); John J Eddleston, Jack The Ripper: An Encyclopedia (2001); Chris Miles, On the Trail of a Dead Man: The Identity of Jack<br />

the Ripper (2004).<br />

Ripperologist 146 October 2015 4

Indeed, courtesy of modern profiling and associated databases, serial killers who wade-in to “assist” police<br />

investigations into their own crimes are not an unkown species. It is the very essence of the accusation levelled<br />

at Hutchinson.<br />

Author Garry Wroe uses the example of StephenYoung who came forward to help police looking into the murder<br />

of Harry and Nicola Fuller only after his cover had been blown. A not dissimilar scenario to George Hutchinson who<br />

came forward belatedly after inquest testimony by Sarah Lewis compromised his presence outside Miller’s Court<br />

in the early morning hours before canonical fifth victim Mary Kelly was murdered there.<br />

It is not the aim of this article to go over all the arguments against George Hutchinson, though a few highlights<br />

and the odd personal elaboration may help provide a quick recap:<br />

● By his own admission Hutchinson had known Kelly for three years, and had given her money in the past.<br />

● He resided at the Victoria Home for Working Men on the corner of Wentworth and Commercial Streets, in<br />

the very heart of what has been dubbed “Ripper Central”.<br />

● He waited outside Miller’s Court for about three-quarters of an hour in late autumn on a rainy night when<br />

temperatures got down to less than 4 degrees Celsius (39 degrees Fahrenheit), after having walked back to<br />

London from Romford, roughly 12 miles (20 kilometres).<br />

● In a report in The Times, Hutchinson says that he eventually tired of his vigil, and places himself inside<br />

Miller’s Court, directly outside Kelly’s room.<br />

The description of the suspect in his witness statement, who he momentarily observed in poor light accompanying<br />

Kelly, is not only overly detailed but downright fanciful, laden with all the stereotypical projections about Jack the<br />

Ripper then current. While every other credible sighting ranged between fleeting and to the point, Hutchinson’s<br />

reads like a screenplay. Here he is quoted in a report from the Pall Mall Gazette of 14 November 1888. Part of it<br />

reads:<br />

He was wearing a long, dark coat, trimmed with<br />

astrachan, a white collar, with black necktie, in which<br />

was affixed a horseshoe pin. He wore a park of dark<br />

“spats” with light buttons, over button boots, and<br />

displayed from his waistcoat a massive gold chain.<br />

His watch chain had a big seal, with a red stone<br />

hanging from it. He had a heavy moustache, curled<br />

up, dark eyes, and bushy eyebrows... He looked like a<br />

foreigner... The man carried a small parcel in his hand<br />

about eight inches long, and it had a strap around it.<br />

He had it tightly grasped in his left hand. It looked<br />

as though it was covered with dark American cloth.<br />

He carried in his right hand, which he left upon the<br />

woman’s shoulder, a pair of brown kid gloves. One<br />

thing I noticed, and that was that he walked very<br />

softly.<br />

George Hutchinson watches Mary Kelly walk off with “the perfect villain”<br />

From Famous Crimes, 1903<br />

Author Bob Hinton called it, “totally theatrical... the perfect villain”.<br />

Hutchinson’s statement to police describes the “Jewish appearance” of the suspect in a case heavy in anti-<br />

Jewish overtone.<br />

This was loudly on display on the night of “the double-event” when canonical victims Elizabeth Stride and<br />

Catherine Eddowes were killed, and which preceded Kelly’s murder by some forty days. There was the anti-<br />

Semitic shout of “Lipski” directed at witness Israel Schwartz during the attack on Stride outside a Jewish club,<br />

the proximity of Eddowes’ murder site to the Great Synagogue, and the wording of the Goulston Street graffito<br />

attributed to the Ripper, “the Juwes are the men That Will not be Blamed for nothing”.<br />

The Wentworth Model Dwellings where the graffito was found with a portion of apron belonging to Eddowes,<br />

was on a direct path from the scene of her murder to Hutchinson’s lodgings. It lay also on the most logical side of<br />

the street for such an escape route, with the Victoria Home for Working Men practically around the corner, only<br />

than a few minutes walk.<br />

Ripperologist 146 October 2015 5

His detractors have also pointed to the internal inconsistencies and niggling contradictions in Hutchinson’s<br />

evidence which are many, and gnaw at some modern-day researchers.<br />

One discrepancy that was pursued by police in 1888 was his claim that he had volounteered his important<br />

information to an officer on the street in the days before Kelly’s inquest had wrapped up, and prior to officially<br />

making contact with police. Despite an extensive search, the policeman was never located. This has left Hutchinson<br />

open to the accusation that he waited three days to come forward only because evidence provided at the inquest<br />

made it clear to him he had been observed at the scene.<br />

As an exercise, if we were to take away that part of Hutchinson’s statement which could be seen as exculpatory,<br />

what remains? A lurking vigil at Miller’s Court not long before Kelly was murdered, which is backed up by Sarah<br />

Lewis’ inquest testimony.<br />

Many Ripperologists counter by proposing that he was one of a multitude of East End poor, and may have just<br />

been trying to cash-in on his five minutes of fame rather than being Jack the Ripper. Others still, if not most,<br />

absolve him altogether on the basis that Abberline passed him fit as a legitimate witness.<br />

But there may be more to know, which does not bode well for such exonerating interpretations. New research<br />

has come to light...<br />

Forbes, New South Wales, 1896. Not quite the end of the earth, but at the time, some might have thought it<br />

viewable from there - especially an Englishman 3 looking to disappear. But staying ahead of British justice required<br />

laying low, even in the colonies.<br />

No such luck. On Tuesday, 1 December, his Honor Judge Docker<br />

presided over a trial in a case of “indecent exposure”. In earlier phases<br />

of the legal process the charge had been described in media reports as<br />

“indecently assaulting two boys”, confirmed as such in the New South<br />

Wales Police Gazette of 11 November 1896. The victims were aged 11<br />

and 8.<br />

Over the course of three editions spanning late October to early<br />

December, the Forbes and Parkes Gazette had provided details of<br />

proceedings, culminating in the following account:<br />

His Honor summed up very strongly against prisoner who had no<br />

defence whatever to offer, and the jury after a retirement of only<br />

five minutes, returned into Court with a verdict of guilty.<br />

Judge Docker then delivered sentence:<br />

I am sorry that owing to the charge which is laid against you and of<br />

which you have been found guilty, I am unable to order that you be<br />

whipped, were I able I certainly should give it you. The sentence<br />

of the Court is that you be imprisoned for two years with hard<br />

labor in Bathurst gaol.<br />

As late as the committal hearing, the charge still seemed to be that<br />

of indecent assault according to media coverage at that moment and<br />

Judge Ernest Brougham Docker<br />

previously. Indeed, the facts of the case were considered too shocking<br />

for proceedings to go on as normal. The court reporter described them<br />

“of a most revolting nature and totally unfit for publication”.<br />

After hearing evidence - which was of such a nature that the Bench decided to hear it with closed doors<br />

- the prisoner was committed to stand his trial at the next Court of Quarter Sessions to be holden at<br />

Forbes on 1st December next.<br />

The man in the dock was George Hutchinson a “stranger” or foreigner, no initials. He would plead “not guilty”,<br />

be placed on remand, and court room events play out in the manner described.<br />

3 An early version of this article used the term ‘Cockney’.<br />

Ripperologist 146 October 2015 6

Crew and Passenger list of the Ormuz, with Geo. Hutchinson listed fourth from the top<br />

Corresponding documentation from Bathurst gaol refer to him as prisoner 1166, born in England, who arrived<br />

on board the Ormuz in 1889.<br />

Built in Glasgow and launched in 1886, the RMS Ormuz serviced the London to Melbourne and Sydney run.<br />

Boasting a top speed of 18 knots, it had arrived from the port of London and deposited Hutchinson in the colony of<br />

New South Wales on 29 October, aged 29. This would tally with the George Hutchinson of the previous November.<br />

The relevant Sydney port authority document lists his surname as “Hutchinson”. The given name is abbreviated<br />

to “Geo” - a common truncation for George at the time, and coincidentally the same used by Abberline’s witness<br />

of that name in 1888 to sign the second page of his statement. It also has him down as “British” and one of the<br />

“crew”.<br />

There is no other listining of this “crew” member easily at hand in the nautical record. This is consistent with<br />

information from the prison file which refers to his arrival in the colony with a single entry, 1889. He does not<br />

appear in Australian documents for any of the Ormuz’s readily verifiable arrival dates into Sydney despite trawling<br />

over records covering 5 years between July 1887 and July 1892, or 11 other voyages 4 . There may be other of the<br />

Ormuz’s voyages to identify within this or broader timeframe, which is why research is ongoing.<br />

To be sure, the net will also require to be cast beyond the silhouette of the Ormuz. There may be scope here<br />

according to online forums for early leads to develop - but only if they can conform more readily with information<br />

proferred by the Ormuz’s records, mindful too of those contained in the prison document. The best of these<br />

presently, seems problematic on numerous fronts. There is a G. Heukhison as transcribed (in error for Hutchinson<br />

or variation of) who appears once in the New South Wales record. On that occasion he was 28 in October 1886, a<br />

ship’s trimmer. His vessel was the Elamang of Sydney with a tonnage of less than a third the Ormuz’s, and seems to<br />

have limited its runs up the coast between the colonial capitals of Melbourne and Sydney. But for a few northern<br />

Europeans, the crew were all “British” as colonial subjects then were. There were no “Australians” until 1901<br />

when the six colonies formed the Commonwealth of Australia.<br />

So as it stands, the evidence suggests George Hutchinson’s trip from London on the Ormuz with an arrival date<br />

of October 1889 may well have been a one-off. There are other reasons for suspecting as much. The following<br />

discussion might serve to broaden the horizon.<br />

Nowhere in the extant record was witness Hutchinson known to be a sailor, although in Tom Cullen’s Autumn of<br />

Terror (1965) he is referred to as a night watchman.<br />

Hutchinson’s station is listed as “A.B.” or able seaman, meaning an unlicensed member of the deck department,<br />

often working in relatively menial roles like watchstander, simple workman or other general maintenance duties.<br />

There were three ordinary seamen (“O.S.”) on board, all younger than Hutchinson.<br />

A nautical career seems somewhat incongruous with the Bathurst gaol record of 1897 which lists his occupation<br />

previous to conviction as “tinsmith”, and information recorded by the court reporter in Forbes in 1896 which<br />

describes him as “labourer”. 5 How to make sense of this?<br />

4 July 1887; March 1888; November 1888; March 1889; March 1890; July 1890; November 1890; March 1891; July 1891; November,<br />

1891; July 1892.<br />

5 See Addendum III for corroboration.<br />

Ripperologist 146 October 2015 7

RMS Ormuz<br />

Abberline described his witness<br />

in an official document as being “at<br />

present in no regular employment”,<br />

while media reports in 1888 refer<br />

to him as a “labourer”. What seems<br />

consistent is both encompass the<br />

lesser skilled end of the professional<br />

spectrum. Normally, London’s<br />

unskilled and semi-skilled urban poor<br />

had few means to travel the world. A<br />

working passage would have offered<br />

one way, particularly so during late-<br />

August, early-September 1889 when<br />

the Great London Dock Strike was<br />

at its height, encouraging unskilled<br />

“blackleg” labour onto ships to<br />

replace unionised elements. 6,7<br />

By 22 August the whole of the dock system had been closed down. Just six days later it was estimated 130,000<br />

men were on strike from stevedores to seamen, firemen, lightermen, watermen, dockmen, bargemen, plus other<br />

tradesmen and women in solidarity. 8 Might this provide context?<br />

It is known from contemporary Australian and British media reports covering the strike that the Ormuz was the<br />

subject of international controversy at that moment, “having shipped blackleg crews of seamen and firemen”. 9<br />

Another headline referencing the “Orient liner Ormuz” reads, “Boycotting Vessels Manned By Blacklegs”. 10<br />

Specifically, these reports referred to the journey the vessel was in the process of undertaking with George<br />

Hutchinson on board.<br />

In the very days the ship was making ready to leave for the Australian colonies, a manifesto had been cabled<br />

from the Seamen and Fireman’s Union in Britain to their brethren at the Wharf Labourers’ Union (an Australian<br />

organisation which had played a crucial role in support of the industrial action in London). The cry across the<br />

ocean was clear: brothers, do not load or unload the Ormuz! 11 Or to put it in the Australian vernacular, the crew<br />

are bodgie. 12<br />

This might explain why the passenger list describes Hutchinson’s station as able seaman. There would have<br />

been no means or desire to write the alternative, as might otherwise have jumped out of the technical manual of<br />

organised labour: scab. Consistent with this, the official Australian record only ever lists him henceforth as either<br />

“labourer” or “tinsmith”. Nowhere has the able seaman, so-called, resurfaced to date.<br />

The industrial action wasn’t just news of international importance, its immediacy reached right into the heart<br />

of the East End in practical ways. The area’s workforce had an integral relationship with the London port system.<br />

Its newest and easternmost expression, Tilbury dock, a further twenty miles downstream, handled roughly half<br />

the Thames’ tonnage 13 and is where the Ormuz was moored when in port.<br />

In City of Cities, author Stephen Inwood describes the strikers’ “daily midday procession in August and<br />

September” which made its way west through the heart of Whitechapel along Commercial Road to Leadenhall<br />

Street and Tower Hill.<br />

6 Stephen Inwood, City Of Cities, Pan Macmillan 2005, pp101-103.<br />

7 Tilbury was one of the docks of the London port system involved in the strike: Stephen Inwood, City Of Cities, p101.<br />

8 www.portcities.org.uk/london/server/show/ConNarrative.77/chapterId/1855/The-Great-Dock-Strike-of-1889.html.<br />

9 12 September, 1889, Dundee Courier, p.3.<br />

10 13 September, 1889, The Advertiser (Adelaide), p.4.<br />

11 13 September 1889, The Argus (Melbourne), p.5.<br />

12 Bodgie also bodgy: in the Australian slang means, inferior, false, counterfeit.<br />

13 Stephen Inwood, City Of Cities, Pan Macmillan 2005, p. 22; see also: Chris Jenks, Urban Culture: Critical Concepts in Literary and<br />

Cultural Studies, Volume 4, Routledge 2004, pp.156-7.<br />

Ripperologist 146 October 2015 8

He provides a colourful contemporary eyewitness account:<br />

There were burly stevedors, lightermen, ship painters, sailors and firemen, riggers, scrapers, engineers,<br />

shipwrights, permanent men got up respectably, preferables cleaned up to look like permanents, and<br />

unmistakable casuals with vari-coloured patches on their faded greenish garments; Foresters and Sons<br />

of the Phoenix in gaudy scarves; Doggett’s prize winners, a stalwart battalion of watermen marching<br />

proudly in long scarlet coats, pink stockings, and velevet caps, with huge pewter badges on their breast,<br />

like decorated amphibious huntsmen; coalies in wagons fishing aggressively for coppers with bags tied<br />

to the end of poles... Skiffs mounted on wheels manned by stolid watermen; ballast heavers laboriously<br />

winding and tipping an empty basket.<br />

The industrial action was noted for its high level of organisation and discipline. It was not just effective, it was<br />

conducted with dignity, and violence was avoided. 14<br />

The Ormuz had been due to leave 15 on the evening of Friday the 13th but the strike had held things up. In<br />

desperation, sixteen clerks from the Orient Line’s Fenchurch Avenue city office plus a bit of hired muscle from<br />

Liverpool had to be brought in to act as stevedores under the taunts of picketers. With only the odd accident and<br />

a negligible delay to its schedule “the pseudo dockmen” 16 as they were described in the media, managed to get<br />

the Ormuz loaded and she steamed out of port in the early hours of the next day, Saturday the 14th.<br />

At the very moment the Ormuz was making final preparations to cast-off 17 an agreement was being signed to<br />

bring the Great London Dock Strike of 1889 to a close after five weeks. In the end it had taken the intercession<br />

of none other than the city’s lord mayor, Cardinal Manning, 18 hailed a hero by dockers and seamen forever more.<br />

Their demands met, the strikers began to return to work on Monday, 16 September. 19<br />

Union-busting exploits aside, there is another possibility which could have accounted for Hutchinson’s presence<br />

on the ship:<br />

The cheapest way of travelling on the Ormuz was as a stowaway, who once discovered were usually put<br />

to work as a member of the crew”. 20<br />

Press-ganged stowaways as some of the crew may have been, the Ormuz’s greater claim to fame was its touted<br />

status as “the fastest ship in world”, as described in 1887 in the Melbourne Daily Telegraph. It had managed to<br />

place the great “metropolis of the world”, London, “within twenty-seven days six hours of its antipodes”. The<br />

Ormuz could steam from London to Sydney in 30 days; 42 days with passengers on board.<br />

Which begs the question, what might have prompted George Hutchinson to gain passage on the “fastest ship in<br />

the world” and flee to the ends of the earth? Did the Great London Dock Strike offer the perfect means during a<br />

period of renewed searching for the Ripper and a heightened police presence on the streets?<br />

In the early hours of 17 July, 1889, Alice McKenzie was found murdered with her throat cut, her clothes pulled<br />

up, exposing her abdomen which had been slashed. Her body was found in Castle Alley, just around the corner<br />

from George Hutchinson’s last known address at the Victoria Home, or two minutes’ walk.<br />

The wound to the left side of her neck was sufficiently severe that H Division police surgeon Dr George Bagster<br />

Phillips believed death was probably “instantaneous”. 21 The Times of 19 July reported:<br />

The wound in the neck was 4 inches long, reaching from the back part of the muscles, which were<br />

almost entirely divided. It reached to the fore part of the neck to a point 4 inches below the chin. There<br />

was a second incision, which must have commenced from behind and immediately below the first. The<br />

cause of death was syncope, arising from the loss of blood through the divided carotid vessels.<br />

14 Stephen Inwood, City Of Cities, Pan Macmillan 2005, p.103.<br />

15 Reading Mercury, 7 September 1889, p.7.<br />

16 The Herald, 23 September, p.3.<br />

17 The Essex Newsman (The Herald), 21 September 1889, p3.<br />

18 Old Thunder: A Life Of Hilaire Belloc by Joseph Pearce, Ignatius Press, San Francisco 2002.<br />

19 www.portcities.org.uk/london/server/show/ConNarrative.77/chapterId/1865/The-Great-Dock-Strike-of-1889.html.<br />

20 historyhackblog.wordpress.com/tag/ship.<br />

21 The Times, 19 July 1889.<br />

Ripperologist 146 October 2015 9

The conclusions of his colleague Dr Thomas Bond are worth quoting (see below). He had conducted the postmortem<br />

on Mary Kelly. At the request of Assistant Commissioner Robert Anderson in October 1888 he had prepared<br />

a report pooling all the medical and inquest testimony on the canonical victims prior to Kelly, confirming they<br />

were victims of the same perpetrator. In the intervening period Dr Bond’s discerning judgement was brought to<br />

bear when he examined the body of Rose Mylett and dismissed the hypothesis she had been murdered by the<br />

Ripper.<br />

Upon conducting a medical investigation of the injuries suffered by Alice McKenzie he reported:<br />

I see in this murder evidence of similar design to the former Whitechapel Murders, viz: sudden<br />

onslaught on the prostrate woman, the throat skillfully & resolutely cut with subsequent mutilation,<br />

each mutilation indicating sexual thoughts & a desire to mutilate the abdomen and sexual organs. I<br />

am of opinion that the murder was performed by the same person who committed the former series of<br />

Whitechapel Murders.<br />

On arriving at the scene of the crime, Chief Commissioner James Monro had formed a similar view which he<br />

reported to the Home Office: 22<br />

...the murderer...I am inclined to believe is identical with the notorious ‘Jack the Ripper’ of last year.<br />

Alice McKenzie walked along grey streets in the East End and inhabits<br />

a parallel grey area after death. She is not counted as a canonical victim<br />

of Jack The Ripper, though some Ripperologists dissent. This mirrors<br />

differing official opinions in 1889. Dr Bond and Chief Commissioner<br />

Monro’s assessment was not shared by the police hierarchy. That it<br />

was not, is in considerable part due to the opinion of Dr Phillips who<br />

concluded that:<br />

I cannot satisfy myself, on purely anatomical & professional<br />

grounds that the perpetrator of all the ‘Wh Ch. murders’ is our<br />

man. I am on the contrary impelled to a contrary conclusion...<br />

There are good reasons why Dr Phillips’ view won out. By July<br />

1889 he was a veteran well versed in the case, having participated in<br />

postmortems on four of the five canonical victims. Understandably, his<br />

opinion carried weight. But it is also true that the higher echelons of<br />

the Criminal Investigation Department carried bitter memories of their<br />

perceived failure the previous year. The often vitriolic press campaign<br />

directed against them had not only fanned the flames of public panic<br />

but directed much odium at police.<br />

Metropolitan Police Commissioner Sir Charles Warren had resigned<br />

nine months earlier, on the same day Mary Kelly’s body was found.<br />

Long assumed to have been a political victim of the Ripper, in reality<br />

he seems to have resigned on a technicality: penning an unauthorised<br />

article responding to broader media criticisms of the police.<br />

Alice McKenzie<br />

This was the charged political environment still fresh in everyone’s mind. Under such circumstances, Dr Phillips’<br />

postmortem report must have fallen into the police’s lap with a good measure of relief, though the ever hounding<br />

media appear to have sensed it. One accusing headline read, “Jack the Ripper’s Latest Murder Accepted as a<br />

Matter of Course”. 23<br />

Having formed his own opinion within hours of McKenzie’s murder, Monro pressed an extra 42 plain-clothes<br />

policemen onto the streets of Whitechapel for the duration of the next two months. Understandably. Things were<br />

getting heated again. The media and people of the East End were demanding answers with an urgency unseen<br />

since the febrile days after the murder of Mary Kelly.<br />

22 Controversially, Assistant Commissioner (Crime) Robert Anderson claimed in his memoirs in 1910 that Monro had investigated Alice<br />

McKenzie’s murder “on the spot” and concluded she was not a victim of Jack the Ripper – this is in contrast to Monro’s opinion as<br />

stated in his own words in the official record.<br />

23 Jack the Ripper: The Forgotten Victims, Paul Begg and John Bennett, Yale Univ Press 2013, p.176.<br />

Ripperologist 146 October 2015 10

Had things become too much for George Hutchinson as well? Had he struck too close to home this time and<br />

slipped-up? Is it possible that some enterprising detective decided to walk the five or so minute journey from<br />

where Alice McKenzie was last seen alive at the eastern end of Flower and Dean Street, to where she was killed<br />

in Castle Alley and noticed the easiest route led past Hutchinson’s lodgings on the corner of Commercial and<br />

Wentworth Streets? Had Hutchinson, belatedly, made the same realisation himself?<br />

A proactive response may have been his solution, as it had after Kelly’s murder when he came forward as a well<br />

meaning witness. The scenario dovetails with a flight to New South Wales aboard the Ormuz in September 1889,<br />

and the facts fit when considering what is known about the George Hutchinson who arrived in New South Wales<br />

and later served time in Bathurst gaol.<br />

The prison record describes a man whose level of education<br />

consisted of being able to read and write, consistent with<br />

witness Hutchinson who signed all three pages of his police<br />

statement in 1888, suggesting he was able to verify its contents<br />

to his satisfaction by reading it.<br />

Hair colour is recorded as brown, eyes blue, the accompanying<br />

photo shows a moustache. His height is recorded as 5’5 & ½’’<br />

and weighing 154 lbs, which would put him in the stocky range<br />

and consistent not only with Sarah Lewis’ inquest testimony<br />

but that of witnesses claiming to have seen the Ripper.<br />

The images of prisoner 1166 recall Israel Schwartz’s<br />

description of the “rather stoutly built” 24 moustachioed<br />

man seen attacking Elizabeth Stride in the minutes before<br />

her murder, particularly the reference to his “full face” and<br />

“broad shoulders” (age about 30, height 5’5”, complexion fair,<br />

hair dark). 25<br />

Indeed, based on historic witness accounts, modern<br />

investigators from Scotland Yard compiled a physical<br />

description of Jack the Ripper in 2006: he was a man of<br />

medium height, between 5’5’’ and 5’7’’, stout build, between<br />

25 and 35 years of age.<br />

Which brings us to the issue of Hutchinson’s year of birth. In<br />

From Hell:The Jack the Ripper Mystery pioneering Hutchinsonaccuser<br />

Bob Hinton described him being 28 in 1888, basing<br />

himself on newspaper reports. 26 More recent forum postings<br />

attributed to Hinton seem to imply this is less certain, 27<br />

while definitive source material from the period paints but a<br />

thumbnail sketch - allbeit one consistent with his proposition.<br />

George Hutchinson as he appears on his prison record, 1897<br />

Realistically, the question is “fraught” to quote from an earlier published version of this article, 28 and the<br />

reason why it introduced the broader discussion of age with a cautionary advisory that 1860 was not a concrete<br />

foundation, but the best presently available. 29<br />

The George Hutchinson who arrived in Sydney on 29 October 1889 was 29 according to the shipping master’s<br />

records, in other words, born 1859 or 1860. This sits well but less than perfectly with the date of birth cited in<br />

the prison document (1861) which points ultimately to said shipping records.<br />

24 The Star, 1 October 1888.<br />

25 HO 144/221/A49301C, ff 148-59.<br />

26 Bob Hinton, From Hell: The Jack the Ripper Mystery (1998), Old Bakehouse Publications 1998; p.217.<br />

27 ‘George Hutchinson George Hutchinson from Romford?’, www.jtrforums.com/showthread.php?t=13917.<br />

28 Ripperologist 146 “sneak preview”.<br />

29 See also: Garry Wroe, Jack the Ripper: Person or Persons Unknown (2002); John J Eddleston, Jack The Ripper: An Encyclopedia<br />

(2001); Chris Miles, On the Trail of a Dead Man: The Identity of Jack the Ripper (2004).<br />

Ripperologist 146 October 2015 11

I had wondered whether the discrepancy might be explained by clerical error. However, what I referred to as<br />

a speculative birthday line some time between early December and early March is very unlikely to have been in<br />

play for the purposes of this article. I am pleased to remove it from present calculations together with the George<br />

Hutchinson it attached to and who was born in Shadwell on 10 December 1859. 30<br />

We are left frustratingly, with a year of birth and chronological age as stated in the Australian documents<br />

which contradict and support one another simultaneously. Be that as it may, the gaol record refers to, and crossreferences,<br />

information verifiable in the shipping files and together they cast a consistent net around Hutchinson’s<br />

date of birth. Except for this dilemma, in all other details, it would seem clear they refer to the same man.<br />

A 29-year-old Englishman is recorded arriving in Australia on a ship from London within a year of Mary Kelly’s<br />

murder, a few months after Alice McKenzie’s. A spree of violent mayhem came to an end in the East End.<br />

The only Ripper-like murder after McKenzie’s was that of Francis Coles in 1891, but police were sure they<br />

had their man when they charged her partner James Sadler, even after the case fell apart. Whatever Sadler’s<br />

involvement if any, there were some decidedly non-Ripper facets to Coles’ injuries, particularly the lack of<br />

mutilations. Students of the case are broadly in agreement that Jack the Ripper was probably not involved. To all<br />

intent, his crimes came to a halt no later than July 1889, on the eve of George Hutchinson’s departure for New<br />

South Wales.<br />

It was ultimately in this colony, seven years after disembarking, where he found himself charged before a court<br />

with indecently assaulting two children. Though convicted of indecent exposure, the offences were particularly<br />

shocking according to media coverage.<br />

Physically, he fits Sarah Lewis’ description of witness George Hutchinson from 1888. It is not just Lewis’<br />

testimony that tallies. Various descriptions of Jack the Ripper match the newly gleaned information presented<br />

here, as the work done by the Scotland Yard team in 2006 attests.<br />

It is worth adding that the information from Bathurst gaol states he was carrying a few scars and injuries,<br />

recorded as identifying marks or special features: a broken nose, a broken little finger on his right hand, a broken<br />

right knee, and a scar on his left breast. His religion is given as Church Of England.<br />

There is more work to be done, for facts to be flushed out and nailed down, in turn building a platform for<br />

research to proceed. Until then, an otherwise interesting report like the following is limited in its value to<br />

spurring on further enquiry.<br />

It comes from the Sydney Morning Herald which carried in-depth coverage of an inquest into a corpse fished<br />

out of the Lachlan River near the now abandoned hamlet of Grudgery about 16 miles downstream from Forbes. In<br />

other contemporary Australian reports it was referred to as “The New South Wales Mystery”. 31 The news report is<br />

dated 29 October 1895.<br />

MYSTERIOUS MURDER NEAR GRUDGERY<br />

BY TELEGRAPH<br />

(FROM OUR CORRESPONDENT)<br />

FORBES, Monday.<br />

The Coroner, Mr Sowter, continued the inquest on the body of the man found in the Lachlan River at<br />

Grudgery on the 20th instant at the courthouse to-day. The evidence of Dr McDonnell, Government<br />

medical officer was all that was forthcoming. He had searched and examined the body thoroughly,<br />

besides taking a number of photos, which were produced and put in as evidence. The back of the skull<br />

was knocked in, as though by a hammer or tomahawk. Around the waist was a trouser strap, also a rope<br />

tightly knotted at the rear, and attached to which was 16 yards of No. 8 eight wire; also a bag with the<br />

bottom rotted out. The bag had evidently been fastened to the body, and is supposed to have contained<br />

weights for keeping the body underwater, but as soon as the bag rotted the weights were lost and the body<br />

rose to the surface. The body was in a frightfully decomposed state, the flesh having been stripped off<br />

the hands, shins, thighs, &c. The clothes were also perfectly rotten. Nothing was found on the deceased<br />

except a knife, tobacco, and matches in one of the waistcoat pockets. He appeared to have been a stout<br />

30 www.jtrforums.com/showthread.php?p=278839#post278839.<br />

31 The West Australian, Friday 1 November, 1895.<br />

Ripperologist 146 October 2015 12

greyish man about 50 years of age, with good teeth, a short stubbly grey beard, and short grey hair. After<br />

hearing the evidence and an address by the Coroner, the jury return the following verdict:– “We find<br />

that the said man, name unknown, was found in the River Lachlan, near Grudgery, in the colony of New<br />

South Wales, on or about 20th October instant: we also find that the deceased died from injuries to the<br />

brain caused by a fracture of the skull: and we further find that the said man, name unknown, was some<br />

months ago wilfully and feloniously killed and murdered by some person or persons to us jurors unknown.”<br />

It cannot be ascertained how long the body been the water, but it had evidently been there for some<br />

months. The man is unknown to the police, but there is no doubt whatever that he has been the victim<br />

of a cruel and brutal murder. At the conclusion of the inquest the foreman of the jury returned special<br />

thanks to Dr McDonnell for the information he had given them, thus considerably lightening their<br />

duties.<br />

A cautionary emphasis attaches in presenting this report because there is nothing to suggest Hutchinson was<br />

involved, or anything remotely on the Ripper radar involving the murder of a male, let alone with a fatal, bluntinstrument<br />

attack to the skull. However, the geography and general chronology triggers curiosity.<br />

Ultimately, the inquest reporting of the ‘New South Wales Mystery’ of 1895 is presented with a desire to share<br />

information come upon during research. Any attempt to give it context is beyond the scope of this article.<br />

Besides, there is much to digest considering what has come to light with the documents proferred here,<br />

tangible as they are, and consistent with the tale of southern flight they would recount.<br />

More research beckons, but even at this stage the fresh evidence adds a new dimension to suspicions long held<br />

by many Ripperologists. The facts match-up remarkably well. If this is the George Hutchinson, then the case for<br />

him being Jack the Ripper has just been strengthened considerably.<br />

After all this time, dare we believe it is him?<br />

Addendum I 32<br />

It should be noted that there is another George Hutchinson, an Englishman, that appears in the record at about<br />

this time, but it seems unlikely he is the same George Hutchinson who arrived in Sydney on the Ormuz or the<br />

witness from 1888 (if indeed these two are different men):<br />

a. The shipping document from the British end of his journey describes him as 28 in 1894 - arriving in Sydney<br />

on the RMS Ophir on 3 November 1894 - no age is given for him in the corresponding Australian record.<br />

b. The British record describes him as a “farmer”. There is no reference to occupation in the Australian<br />

version.<br />

c. The shipping document available in New South Wales government archives confirm the English record of<br />

him travelling as a normal passenger, which suggests this George Hutchinson could afford the price of<br />

passage.<br />

Addendum II 33<br />

• There is a third-class passenger, a T. Hutchinson, no age or nationality given, listed on the Ormuz’s arrival<br />

into Sydney in early March 1890. The initial “T” could not be mistaken for a “G” when compared to examples of<br />

that initial or the letter “g” appearing on the document. This is consistent with its transcription, which also<br />

gives the passenger’s initial as “T”.<br />

• The corresponding British record lists a passenger by the name of Tom Hutchinson departing London for<br />

Sydney in January 1890 on board the Ormuz. He is recorded as single, an English male of 25 years of age.<br />

More than likely, he is the T. Hutchinson appearing in the Australian maritime record.<br />

32 State Records Authority of New South Wales: Shipping Master’s Office; Passengers Arriving 1855 - 1922; NRS13278, [X201] reel 524;<br />

also, Ancestry.com UK, Outward Passenger Lists, 1890-1960 [database online].<br />

33 New South Wales, Unassisted Passenger Lists, 1826-1922; UK, Outward Passenger Lists, 1890-1960.<br />

Ripperologist 146 October 2015 13

Addendum III 34<br />

The New South Wales Police Gazette of 17 August 1898 details Hutchinson’s release from Darlinghurst gaol in<br />

Sydney at the end of his two year sentence. The date might suggest he had been in police custody since August<br />

1896.<br />

It states his “trade” as “labourer” consistent with the court reporter’s description in 1896.<br />

The matter of his exact year of birth is further muddied because it is listed as 1862.<br />

His eyes are described as “brown” and hair “dark brown”, though the information accompanying his photographic<br />

record from Bathurst gaol, says the eyes were “blue” and hair simply “brown”.<br />

In the column under “Remarks, and if previously convicted” it states “previously convicted”. It is unclear to this<br />

writer whether this is a reference to the recorded offence of 1896 or another prior conviction.<br />

Sources<br />

www.poheritage.com/Content/Mimsy/Media/factsheet/94092ORMUZ-1886pdf.pdf; Melbourne Daily Telegraph, 1887 as quoted at<br />

historyhackblog.wordpress.com/tag/ship; Forbes and Parkes Gazette (State Library of NSW: microfilm collection, RAVFM4/248, roll<br />

n# 5: Friday 30 October 1896, p.2 - article dated 29 October 1896: Tuesday 3 November 1896, p.2 - article dated 30 October 1896:<br />

Friday 4 December 1896, p.2 - article dated 1 December 1896; State Records Authority of New South Wales: Shipping Master’s Office,<br />

Passengers Arriving 1855-1922; NRS13278, [X201] reel 493, reel 524; State Records Authority of New South Wales: NRS1998, [3/5960],<br />

Bathurst Gaol photographic description book, 1874-1930, No. 1166, p.19, reel 5085; ancestry.co.uk, Outward Passenger Lists, 1890-<br />

1960 [database on-line]. Original data: Board of Trade: Commercial and Statistical Department and successors: Outwards Passenger<br />

Lists. BT27. Records of the Commercial, Companies, Labour, Railways and Statistics Departments. Records of the Board of Trade and of<br />

successor and related bodies; The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, England.<br />

34 Posted online by jtrforums.com.<br />

A student of the Ripper case since way-back, STEPHEN SENISE is a freelance journalist. His political analysis has featured in national and<br />

capital city dailies across Australia. Most of his time these days is spent as a stay-at-home Ripperologist dad and occasional 146 October racing 2015 correspondent. 14 He<br />

has a BA (Hons Lit) and previously worked as a ‘secretary & research-assistant’ in the New South Wales Legislative Council.

An Ungoverned Passion<br />

Journalistic Constructions of Mary Pearcey<br />

and the Hampstead Tragedy<br />

By DR SARAH BETH HOPTON<br />

I see when men love women they give them but a little of their lives.<br />

But women when they love give everything.<br />

Oscar Wilde<br />

* * * * *<br />

The Crime<br />

Friday, 24 October 1890. A few minutes past 7.00pm, a clerk named Somerled McDonald was walking home toward<br />

Belsize Park Road when he stumbled upon a woman lying in the road, a jacket thrown across her torso. At first he thought<br />

she was drunk, homeless, or sick - the jacket obscuring his view - and moved to the far edge of the pavement to avoid<br />

her. Something tickled his curiosity though, and he turned back. He bent down and shook her, but her body replied stiffly,<br />

and he was unnerved and ran toward the Swiss Cottage Railway Station to fetch a constable. 1<br />

McDonald led PC Arthur Gardiner back to<br />

the spot where he’d left the woman. When<br />

Gardiner arrived, he removed the jacket.<br />

Underneath was a barely recognisable<br />

woman’s face bespattered with blood and<br />

dirt; her neck cut so severely her vertebral<br />

column and ligaments were exposed.<br />

The post where the body was found. From Famous Crimes<br />

Sgt Brown and Inspector Wright of S<br />

Division (Hampstead) were soon on the<br />

scene, as was Dr Arthur Wells, fetched to<br />

assess time of death. Wells determined<br />

that the woman had not been dead long,<br />

since her legs were still warm and her arms<br />

not quite cold. Brown and Wright collected<br />

evidence including a brass nut dappled with<br />

blood. 2<br />

An ambulance conveyed the body to the Hampstead Mortuary, while Inspector Wright canvassed the neighborhood.<br />

Early information suggested the woman was in the “habit of walking up and down Eton-avenue,” which is to say they<br />

suggested she was a prostitute, but the constables who walked that beat were later paraded before the body to confirm<br />

this theory, and none recognised her. 3 Though it had been two years since the last Ripper victim, Mary Jane Kelly, was<br />

found butchered at 13 Millers Court, the nature of this murder stirred immediate public angst and speculation. 4<br />

1 “Shocking Tragedy at Hampstead.” Herts Advertiser, 1 November 1890. p7.<br />

2 “Trial of Mary Eleanor Wheeler Pearcey.” Old Bailey Proceedings Online. December 1890, www.oldbaileyonline.org.<br />

3 “Woman Brutally Murdered at Hampstead.” Pall Mall Gazette, 25 October 1890. pp4-5.<br />

4 “Terrible Murder at Hampstead.” Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper, 26 October 1890. p1.<br />

Ripperologist 146 October 2015 15

The Ripper Connection<br />

The theory that this woman was another Ripper victim was strengthened when a cab driver told police that a “well<br />

dressed man” hailed him, 5 promising double fare if he would drive full speed to Chalk Farm Station. The presence of<br />

Chief Inspector Donald Swanson (the lead investigator into the Whitechapel murders) at the site where the body was<br />

found was enough for reporters to print what bystanders were already thinking: the devil had again fled Hell for London.<br />

The Pall Mall Gazette led with this the following morning. “The unfortunate victim was seized from behind and<br />

was at once rendered speechless by one large, clean cut of a knife, as in the case of the<br />

women murdered in Whitechapel.” 6 The hasty conclusion is forgivable considering some<br />

similarities appeared to exist in the modi operandi of both killers. Mary Kelly’s throat<br />

was severed to the spine like the woman lying dead in the Hampstead Mortuary, and the<br />

crimes were apparently perpetrated under cover of night and without a single witness.<br />

The description given by the cab driver reified speculations about the Ripper’s physical<br />

comportment. According to the Gazette, police were looking for a man “aged about forty,<br />

nearly six feet high, with a dark moustache, and wearing a light suit and peak cap.” 7 This<br />

description is strikingly similar to that given by Thomas Ede of a suspicious looking man<br />

he thought might have been the Ripper. The man was described as 5ft 8in in height, about<br />

35 years of age with a dark moustache and whiskers. He wore a double peaked cap, dark<br />

brown jacket and a pair of overalls and dark trousers. 8 Regrettably, both descriptions are<br />

generic enough to have fingered virtually every other white, male Londoner living nearby,<br />

and thus proved unhelpful in either case.<br />

Though Swanson left the scene certain he saw none of his nemesis’ handiwork in the<br />

mutilated woman’s corpse, Scotland Yard took no chances. A constable woke Chief Constable<br />

Melville Macnaghten to tell him about the murder at Crossfield Road. Macnaghten relayed<br />

back a message to Inspector Bannister: he would meet him at the mortuary at first light.<br />

Chief Constable Melville Macnaghten<br />

The Pram<br />

Meanwhile, two and one half miles away, Police Constable John Roser was walking his beat in Hamilton Terrace, when<br />

he stumbled upon something curious. Leaning against the garden wall of No. 35 was a baby’s perambulator, a brown rug<br />

draped over it. The handle was broken and the pram seemed wet, though it had not rained. Roser saw blood. He pushed<br />

the pram back to the Portland Town Police Station.<br />

Roser and Inspector Holland, who was on night duty, studied the contents of the pram, finding “partially congealed<br />

blood” in the seat and human hairs sticking to its side, a waterproof apron, 9 and a butterscotch candy 10 wrapped in<br />

robin’s egg blue paper, bespecked with blood. 11<br />

5 “The Hampstead Murders.” Pall Mall Gazette, 25 October 1890. p7.<br />

6 “A Woman Brutally Murdered at Hampstead.” Pall Mall Gazette, 25 October 1890. It seems the PMG also published the theory of<br />

Jill the Ripper, connecting and exploring the possibility it was even Pearcey, in an article titled “The Whitechapel Horror” published<br />

on Valentine’s Day, 1891.<br />

7 Ibid.<br />

8 “The Man Not Found.” The Echo, 17 September 1888.<br />

9 The presence of the waterproof apron particularly would later support theories first proposed by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and later<br />

expanded by William Stewart (1939) that Jack the Ripper was a woman; more specifically a midwife. The theory was not without<br />

logic. Those who wore such aprons commonly practiced the bloody arts of midwifery, surgery, or butchery and could roam the busy<br />

streets of London wearing a besmeared apron without exciting much notice. Though criminal historians like F. Tennyson Jesse, as<br />

well as a preponderance of evidence to the contrary have since debunked the theory that Jack was a Jill, the idea of the Ripper as<br />

a woman proved to be pernicious. In 2006, Ian Findlay, professor of Molecular and Forensic Diagnostics (Marks, 2006) claimed he<br />

could extract DNA from a single cell taken from a strand of hair up to 160 years old. At the time, conventional DNA sampling<br />

methods required at least 200 cells. With samples taken from evidence housed at the National Archives, he extracted DNA from the<br />

gum used to seal the so-called “Openshaw letter” from which he created a profile. Ultimately, Findlay’s results were inconclusive,<br />

but the global press reignited the Jill-the-Ripper theory because Findlay deduced from his partial profile that it was “possible” the<br />

Ripper could be female.<br />

10 “The Victim on Her Way to her Fate.” St Pancras Gazette, 5 November 1890.<br />

11 “Trial of Mary Eleanor Wheeler Pearcey.” Old Bailey Proceedings Online. December 1890, www.oldbaileyonline.org.<br />

Ripperologist 146 October 2015 16

Oliver Smith finds the body of a baby<br />

A Hawker Finds The Baby<br />

Sunday, 26 October 1890. A hawker named Oliver Smith<br />

was walking inside a hedgerow across a vacant lot early in<br />

the morning when he spotted something out of place in the<br />

landscape. As he drew closer, he realised he was peering down<br />

at a dead baby girl and noticed she was missing a tiny shoe<br />

and sock. Smith tracked down a doctor, Dr John Maundy Biggs,<br />

and a constable, PC Dickerson, who removed the baby to the<br />

Hampstead Mortuary where an autopsy was performed to<br />

determine cause of death.<br />

Though Dr Joseph Augustus Pepper had performed countless<br />

autopsies as Master of Surgery at the University of London 12 he<br />

could not say definitively what killed the child. She appeared to<br />

be roughly two years old and was well fed and clean except for<br />

a small smudge of dirt on her cheek. Other than this smudge,<br />

he described in his notes that her lips were pale blue - a sign of cyanosis - due to a lack of oxygen in the blood, which<br />

he believed was caused by asphyxiation. 13 Pepper couldn’t rule out death due to exposure either, though The Times<br />

reported the weather for 25 October as singularly mild.<br />

The Puzzle Pieced Together<br />

The body of the dead child was eventually linked to the bloody perambulator, and finally, to the nearly decapitated<br />

woman decomposing in the Hampstead mortuary. As the details of the case unfolded, Scotland Yard was as surprised as<br />

the public - and perhaps also as relieved - to learn that the murderer was not Jack the Ripper, but a 24-year-old woman<br />

named Mary Eleanor Pearcey (née Wheeler).<br />

Pearcey purportedly murdered Frank Hogg’s wife, Phoebe, and infant child, Tiggie. Hogg being Pearcey’s lover of<br />

several years, the crime was always attributed to jealousy, but the evidence at the scene suggested that Pearcey killed<br />

Phoebe in a fit of rage and murdered the child to either silence her cries, or out of desperation having realised what<br />

she’d done. The murder clearly took place in Pearcey’s kitchen at No. 2 Priory Street. Several witnesses saw Phoebe<br />

pushing the pram along Haverstock Hill, the street on which she stopped at a confectioner’s shop to buy Tiggie a<br />

butterscotch candy, or, more exactly, a toffee candy, and then along Priory Street. Later, she was seen struggling to get<br />

the pram into the hallway at No. 2 at approximately 3.30pm, which aligns with a probable time of death based on body<br />

temperature and weather conditions.<br />

* * * * *<br />

The Nature of Murderous Women<br />

What is the character of tragedy? Aristotle tells us that an act is truly tragic only when it arouses pity and fear. 14<br />

Separated, pity and fear provoke independent responses, but combined, they aggravate inquiry into the depths of<br />

human nature. And so the journalists and writers who broke the story that late autumn morning in 1890 rightly named<br />

the murders of Phoebe and Tiggie Hogg “The Hampstead Tragedy”.<br />

Until the nineteenth century, murder was considered an act of will. Socrates argued that the unrestrained person<br />

acted as such because he lacked self-understanding. Through reason one might willfully restrain the passions that - left<br />

unchecked - so often caused human hurt and fatal harm. Aristotle later finessed this theory, suggesting that human<br />

tragedy was not tied to self-knowledge, but was due to an excess of certain emotions. Such emotion was felt so intensely<br />

among some people they could be driven to act against their better selves.<br />

12 Augustus Joseph Pepper. Biographical entry 1849-1935. www.livesonline.rcseng.ac.uk/biogs/E004458b.html<br />

13 “Trial of Mary Eleanor Wheeler Pearcey.” Old Bailey Proceedings Online. December 1890, www.oldbaileyonline.org.<br />

14 George Whalley, et al. Aristotle’s Poetics. (Montreal, Que: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1997).<br />

Ripperologist 146 October 2015 17

From the mid-nineteenth century, the Judicial Statistics for England and Wales, an annual publication, suggested<br />

that crime in general was falling. There are problems with crime statistics, especially from this period. For example,<br />

Clive Emsley tells us that the Metropolitan Police often reported thefts as lost property, and the disenfranchised were<br />

often suspicious of police and rarely reported crimes. That said, secondary data supports the claim that theft and<br />

violence were in decline by mid-century, and that violent crime in the form of murder - whether committed by men or<br />

women - never figured meaningfully in the statistics. 15<br />

On the whole, men murdered more than women, and when women murdered, they disproportionately murdered<br />

their children or husbands. In fact, by the ‘hungry forties’ more than 90 percent of murders committed by women were<br />

against their children, 16 making women who killed someone other than a child exceedingly rare. Most crimes committed<br />

by women tended to be “victimless,” vagrancy, disordered conduct, or solicitation, for example.<br />

Judith Knelman’s book Twisting in the Wind attempts to classify the other kind of female criminal, the kind who<br />

murdered, and murdered someone other than a child. Knelman catalogues the motives of 50 murderesses she identifies<br />

as “notorious” who killed between 1830-1901. By her estimation, only 22 percent of these 50 women were driven to<br />

murder by passion, 17 making passionate murder of someone other than a child or husband rarer still. Women who killed<br />

their children and husbands were thought of as those who had “sunk to the very depths of humanity,” 18 while women<br />

like Pearcey were thought to suffer a depravity that was almost inhuman. 19<br />

The Mad Murderess<br />

The “murderess,” as reported and constructed in the London press, was<br />

often little more than a binary construction in equal turns described as either<br />

too delicate or too fierce; too calculating or too simple; raving mad or just<br />

plain bad. By the time of the Pearcey trial, educated Victorians believed in a<br />

hardened criminal class composed of hereditary offenders. 20 Several papers<br />

incorrectly published that Pearcey’s father was also a murderer, 21 though<br />

he was not. 22 Pearcey’s father, James Wheeler, was actually a partially deaf<br />

dockworker, who was not hanged for the murder of farmer Edward Anstee,<br />

but died at home in August, 1882, 23 after a work accident resulted in a<br />

ruptured spleen. 24<br />

The criminologist Cesare Lombroso first proposed belief in atavism. His<br />

theories, as well as wide interest in the pseudoscience of physiognomy and<br />

phrenology, which linked mind, body and character, 25 resulted in cultural<br />

practices that attempted to see sexual deviance and criminal behavior within<br />

certain physical characteristics. Lombroso’s theory of criminal behavior was<br />

an earlier example of what Lacan would later term as the “gaze.” Michele<br />

Foucault’s work Discipline and Punish later applied the gaze to criminology.<br />

Cesare Lombroso<br />

15 “Crime and the Victorians.” BBC News, 17 February 2011. Accessed October 12, 2015.<br />

16 Robyn Anderson. Criminal Violence in London, 1856–1875. (PhD Thesis, Toronto, Ont: University of Toronto, 1990).<br />

17 Knelman. Twisting in the Wind. p9.<br />

18 Rachel Short, “Female Criminality 1780-1830.” (Oxford, 1990), p156.<br />

19 Knelman. Twisting in the Wind. p14.<br />