Obura2009-IUCN Congress report - Resilience sessions

Obura2009-IUCN Congress report - Resilience sessions.pdf

Obura2009-IUCN Congress report - Resilience sessions.pdf

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

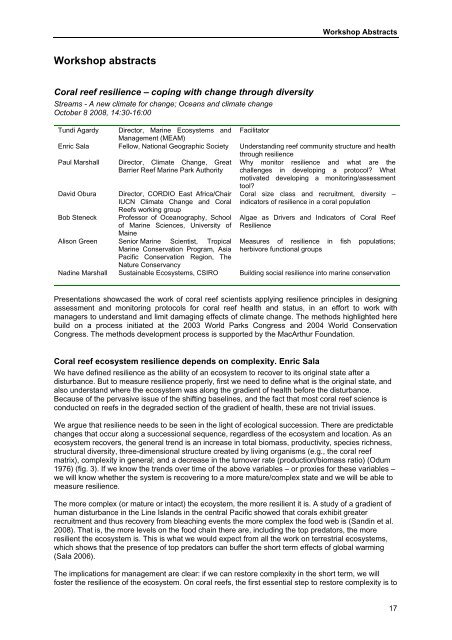

Workshop Abstracts<br />

Workshop abstracts<br />

Coral reef resilience – coping with change through diversity<br />

Streams - A new climate for change; Oceans and climate change<br />

October 8 2008, 14:30-16:00<br />

Tundi Agardy Director, Marine Ecosystems and Facilitator<br />

Management (MEAM)<br />

Enric Sala Fellow, National Geographic Society Understanding reef community structure and health<br />

through resilience<br />

Paul Marshall Director, Climate Change, Great Why monitor resilience and what are the<br />

Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority challenges in developing a protocol? What<br />

motivated developing a monitoring/assessment<br />

David Obura Director, CORDIO East Africa/Chair<br />

<strong>IUCN</strong> Climate Change and Coral<br />

Reefs working group<br />

Bob Steneck Professor of Oceanography, School<br />

of Marine Sciences, University of<br />

Maine<br />

Alison Green Senior Marine Scientist, Tropical<br />

Marine Conservation Program, Asia<br />

Pacific Conservation Region, The<br />

Nature Conservancy<br />

tool?<br />

Coral size class and recruitment, diversity –<br />

indicators of resilience in a coral population<br />

Algae as Drivers and Indicators of Coral Reef<br />

<strong>Resilience</strong><br />

Measures of resilience in fish populations;<br />

herbivore functional groups<br />

Nadine Marshall Sustainable Ecosystems, CSIRO Building social resilience into marine conservation<br />

Presentations showcased the work of coral reef scientists applying resilience principles in designing<br />

assessment and monitoring protocols for coral reef health and status, in an effort to work with<br />

managers to understand and limit damaging effects of climate change. The methods highlighted here<br />

build on a process initiated at the 2003 World Parks <strong>Congress</strong> and 2004 World Conservation<br />

<strong>Congress</strong>. The methods development process is supported by the MacArthur Foundation.<br />

Coral reef ecosystem resilience depends on complexity. Enric Sala<br />

We have defined resilience as the ability of an ecosystem to recover to its original state after a<br />

disturbance. But to measure resilience properly, first we need to define what is the original state, and<br />

also understand where the ecosystem was along the gradient of health before the disturbance.<br />

Because of the pervasive issue of the shifting baselines, and the fact that most coral reef science is<br />

conducted on reefs in the degraded section of the gradient of health, these are not trivial issues.<br />

We argue that resilience needs to be seen in the light of ecological succession. There are predictable<br />

changes that occur along a successional sequence, regardless of the ecosystem and location. As an<br />

ecosystem recovers, the general trend is an increase in total biomass, productivity, species richness,<br />

structural diversity, three-dimensional structure created by living organisms (e.g., the coral reef<br />

matrix), complexity in general; and a decrease in the turnover rate (production/biomass ratio) (Odum<br />

1976) (fig. 3). If we know the trends over time of the above variables – or proxies for these variables –<br />

we will know whether the system is recovering to a more mature/complex state and we will be able to<br />

measure resilience.<br />

The more complex (or mature or intact) the ecoystem, the more resilient it is. A study of a gradient of<br />

human disturbance in the Line Islands in the central Pacific showed that corals exhibit greater<br />

recruitment and thus recovery from bleaching events the more complex the food web is (Sandin et al.<br />

2008). That is, the more levels on the food chain there are, including the top predators, the more<br />

resilient the ecosystem is. This is what we would expect from all the work on terrestrial ecosystems,<br />

which shows that the presence of top predators can buffer the short term effects of global warming<br />

(Sala 2006).<br />

The implications for management are clear: if we can restore complexity in the short term, we will<br />

foster the resilience of the ecosystem. On coral reefs, the first essential step to restore complexity is to<br />

17