to Land

women_in_push-pull

women_in_push-pull

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

32 • From Lab <strong>to</strong> <strong>Land</strong><br />

Mary Nanjala in Uganda, her own poor health, a<br />

shortage of labour in the household and a lack<br />

of income <strong>to</strong> hire labour mean that her desire<br />

<strong>to</strong> expand her push–pull plot is likely <strong>to</strong> remain<br />

unfulfilled.<br />

In Ethiopia, the initial heavy demand for<br />

labour is an obstacle <strong>to</strong> adoption. Households<br />

are based around nuclear rather than extended<br />

families, which means that less labour is available<br />

than in the multi-generational extended<br />

households of the Lake Vic<strong>to</strong>ria region. Although<br />

there are strong traditions of collective farming,<br />

Sue Edwards says “when it comes <strong>to</strong> field<br />

management for something like push–pull, which<br />

is knowledge intensive, you can’t just borrow<br />

farmers from adjacent fields, or families, like you<br />

can with harvesting, sowing or even weeding –<br />

when people will normally get <strong>to</strong>gether <strong>to</strong> work in<br />

a group. For push–pull, the optimum labour you<br />

have available is what you have in your family.”<br />

Sometimes, this is not enough.<br />

Many female farmers do find ways<br />

around the need for labour. Some, particularly<br />

members of Heifer International groups, work<br />

in small groups on each others’ farms until each<br />

member has established a plot. Others cultivate<br />

a collective group plot, sharing the outputs,<br />

adding them <strong>to</strong> group-saving schemes or using<br />

the fodder <strong>to</strong> increase the health and productivity<br />

of pass-on lives<strong>to</strong>ck. Others, like Beryl Atieno,<br />

use their own labour, succeeding against all<br />

expectations.<br />

Food<br />

Most of the female farmers interviewed for<br />

this report see ‘putting food on the table’ as a<br />

woman’s basic responsibility <strong>to</strong> her children. In<br />

the words of Bilha Wekesa, who farmed while her<br />

husband was a schoolteacher, “he educated the<br />

children; I fed them.”<br />

Push–pull increases cereal yields. Many<br />

push–pull farmers describe themselves as food<br />

secure, meaning that they produce enough grain<br />

<strong>to</strong> last from one agricultural season <strong>to</strong> the next,<br />

and most of those who have not yet attained this<br />

goal are getting closer. Mary Otuoma, who farms<br />

a single acre, says that “my priority has always<br />

been <strong>to</strong> have enough until the next harvest”. Last<br />

season, having added a fourth push–pull plot <strong>to</strong><br />

her farm, she obtained a surplus for the first time,<br />

and had some maize <strong>to</strong> sell.<br />

Grace Anyange and her husband support a<br />

household of 13 people on their three-acre farm.<br />

They adopted push–pull in 2012 and have since<br />

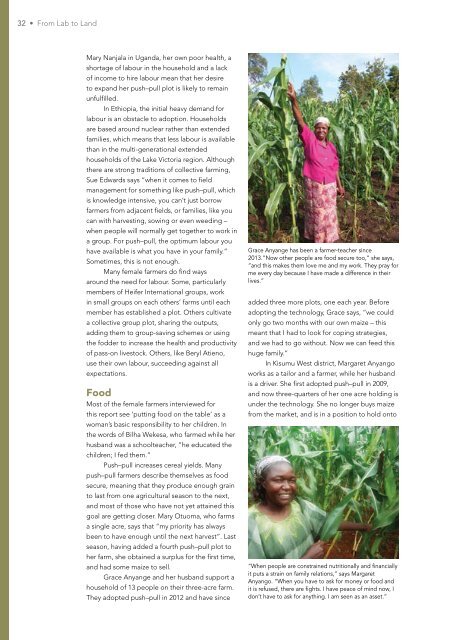

Grace Anyange has been a farmer-teacher since<br />

2013.”Now other people are food secure <strong>to</strong>o,” she says,<br />

“and this makes them love me and my work. They pray for<br />

me every day because I have made a difference in their<br />

lives.”<br />

added three more plots, one each year. Before<br />

adopting the technology, Grace says, “we could<br />

only go two months with our own maize – this<br />

meant that I had <strong>to</strong> look for coping strategies,<br />

and we had <strong>to</strong> go without. Now we can feed this<br />

huge family.”<br />

In Kisumu West district, Margaret Anyango<br />

works as a tailor and a farmer, while her husband<br />

is a driver. She first adopted push–pull in 2009,<br />

and now three-quarters of her one acre holding is<br />

under the technology. She no longer buys maize<br />

from the market, and is in a position <strong>to</strong> hold on<strong>to</strong><br />

“When people are constrained nutritionally and financially<br />

it puts a strain on family relations,” says Margaret<br />

Anyango. “When you have <strong>to</strong> ask for money or food and<br />

it is refused, there are fights. I have peace of mind now, I<br />

don’t have <strong>to</strong> ask for anything. I am seen as an asset.”