DANCE COLLECTION DANSE

3E8Oe3fJp

3E8Oe3fJp

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>DANCE</strong> <strong>COLLECTION</strong> <strong>DANSE</strong><br />

Number 75 <strong>DANCE</strong> THAT LASTS<br />

Fall 2015<br />

New in the Archives: Barbara Cook<br />

Elizabeth Langley:<br />

Embracing Transformation<br />

Moving, in Tandem:<br />

25 Years of Kaeja d’Dance<br />

Finding Mrs. Colville:<br />

WWI Patriotic Performances<br />

in St. John’s<br />

Stephanie Ballard:<br />

An Indelible Mark<br />

Gadfly: The Evolution<br />

of Form

Dance Collection Danse Magazine<br />

Number 75, Fall 2015<br />

New in the Archives: Barbara Cook<br />

by Amy Bowring ........................................................ 4<br />

Elizabeth Langley: Embracing Transformation<br />

by Philip Szporer ........................................................ 8<br />

Moving, in Tandem: 25 Years of Kaeja d’Dance<br />

by Samantha Mehra ................................................. 16<br />

Finding Mrs. Colville: WWI Patriotic Performancces<br />

in St. John’s<br />

by Amy Bowring ...................................................... 24<br />

Stephanie Ballard: An Indelible Mark<br />

by Cindy Brett ........................................................... 31<br />

Gadfly: The Evolution of Form<br />

by Soraya Peerbaye .................................................. 39<br />

Photo: Cylla von Tiedemann<br />

Opening<br />

Remarks<br />

BY MIRIAM ADAMS, C.M.<br />

Last year a dancer visited our offices and came across a book<br />

about a mentor of his; I said that DCD had published it and he<br />

said, “What does that mean?”<br />

DCD has published 39 books. Thirty-Nine. I make this<br />

fact known each time I have the opportunity to speak<br />

publicly about DCD’s achievements. Few outside of<br />

those intimately involved in publishing are aware<br />

of the duration, the intricacies and yes, the anxiety,<br />

of this process. We started in the 1990s by printing<br />

books in our home office and assembling them using<br />

a toaster oven, harvested from the Goodwill, that<br />

Lawrence Adams had fashioned into a book binder.<br />

When we graduated from the toaster oven to a professional<br />

printing company, we ran between 500 and<br />

2000 copies per title, depending on the book’s “imagined”<br />

market; three titles were reprinted several times.<br />

Books sold consistently to universities, professional<br />

schools, bookstores, library services and individuals.<br />

We published memoirs and manuals, biographies,<br />

anthologies and cultural histories, dictionaries and<br />

a bilingual encyclopedia. We worked with emerging<br />

writers, established authors, and those in-between; we<br />

eagerly tracked down the images of dance photographers.<br />

For the Dictionary of Dance (1996) we commissioned<br />

20 contributors who provided “words, terms<br />

and phrases” representing diverse dance genres. For<br />

the Encyclopedia of Theatre Dance in Canada/Encyclopédie<br />

de la danse théâtrale au Canada (2000) we commissioned<br />

43 writers to craft the entries and we worked with an<br />

editor, translator, research co-ordinator/copy editor,<br />

French- and English-language readers. Over the years,<br />

we spent intense hours, days and weeks in conversation<br />

with authors; and in some cases the book’s subject;<br />

and then in further lengthy discussion with designers,<br />

editors, translators and printers. Given that the average<br />

length of time it took to grant a book its life was 3.5 years<br />

(one of them took 8) the writers clearly “did it for love”.<br />

A handful of them received a grant to bulk up DCD’s<br />

modest fee; and with the foresight of prophets, the Dance<br />

and the Writing & Publishing programs at the Canada<br />

Council assisted with several of these books … 9 of the<br />

authors and 7 of the subjects have since passed on.<br />

Working with writers was an inspiring and challenging<br />

exercise. There were only a few tiffs over grammar,<br />

punctuation, language. And in dealing with biographies,<br />

the occasional hefty discourse about the moral responsibility<br />

of whether or not to “exclude” certain facts.<br />

In our March 2008 fiscal year, DCD earned over<br />

$45,000 in book sales – slowing down dramatically<br />

beginning with the financial crisis of that year. Our last<br />

book, Renegade Bodies, was published in 2012. So publishing<br />

has ceased (for a while) as we have evolved into<br />

other equally engaging activities to spread the word<br />

and share the stories about Canada’s dance history.<br />

Who wants to buy a dance book? We have lots.<br />

dcd.ca/shop/<br />

The Magazine is published by Dance Collection Danse<br />

and is freely distributed.<br />

ISSN 0 849-0708<br />

301–149 Church Street, Toronto, ON M5B 1Y4<br />

Tel. 416-365-3233 Fax 416-365-3169<br />

E-mail talk@dcd.ca Web site www.dcd.ca<br />

Charitable Registration No. 86553 1727 RR0001<br />

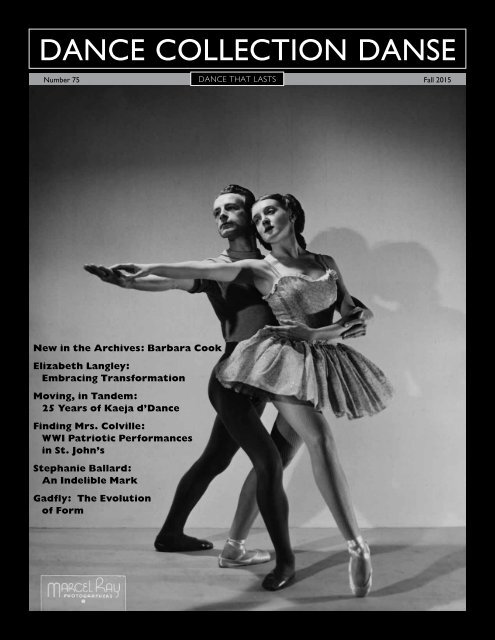

Cover: Walter Foster and Barbara Cook, 1952<br />

Photo: Marcel Ray Photographers<br />

Design/Layout: Michael Caplan michael@michaelcaplan.ca<br />

No. 75, Fall 2015 3

New<br />

in the<br />

Archives<br />

Barbara<br />

Cook<br />

Photo: Travis Allison<br />

BY AMY BOWRING<br />

We recently acquired a small collection<br />

from long-time DCD friend<br />

and supporter Barbara Cook. I first<br />

heard Barb’s name in my early days<br />

at DCD doing research on London,<br />

Ontario’s dance history. In my<br />

interview with London-based ballet<br />

teacher Bernice Harper, she talked<br />

about her 1960s trips to Sudbury to<br />

teach during the summer sessions<br />

at Cook’s Sudbury School of Ballet.<br />

Barbara Cook in Don Gilles’s I Want, I Want<br />

Photo: E.E. Amsden<br />

Members of the Winnipeg Ballet and the<br />

Volkoff Canadian Ballet, May 31, 1948<br />

Born in Hamilton on March 28,<br />

1930, Barbara Cook began her dance<br />

training with Nancy Campbell in<br />

1933. A move to Toronto at six years<br />

old brought Cook to Boris Volkoff’s<br />

studio where she studied with him<br />

and his wife, Janet Baldwin. Cook’s<br />

theatrical training was further<br />

enhanced by a decade with Dorothy<br />

Goulding’s Toronto Children Players.<br />

By 1946 she was performing with<br />

the Volkoff Canadian Ballet. With<br />

Volkoff, she participated in the<br />

his toric first Canadian Ballet Festival<br />

in Winnipeg in 1948; in the 1949<br />

“Salute to Canada” pageant in Mid -<br />

land, Ontario, commemorating the<br />

300th anniversary of the martyrdom<br />

of a group of Jesuit priests; and in the<br />

Canadian Festival of Ballet in New<br />

York City in 1950, which also featured<br />

Ruth Sorel’s group from<br />

Montreal. Cook danced with the<br />

Janet Baldwin Ballet in the 1950s and<br />

par ticipated in all six Canadian<br />

Ballet Festivals. She was part of a<br />

pioneering generation of Canadian<br />

dancers whose efforts ultimately led<br />

to the professionalization of ballet in<br />

this country.<br />

4 Dance Collection Danse

Her introduction to the Royal<br />

Academy of Dancing (RAD) method<br />

came through Janet Baldwin and<br />

Gweneth Lloyd, the indefatigable<br />

Don Gillies<br />

Photo: E.E. Amsden<br />

co-founder of the Royal Winnipeg<br />

Ballet who opened a branch of<br />

her Canandian School of Ballet in<br />

Toronto in the early 1950s. Cook<br />

ultimately became an RAD teacher<br />

and examiner. She taught for Baldwin’s<br />

school from 1951 to 1957 and<br />

was then brought to Sudbury by the<br />

Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers’<br />

Union to teach in a dance program<br />

the union had initiated for its members.<br />

She replaced modern dance<br />

teacher Nancy Lima Dent – a colleague<br />

from the Ballet Festival years.<br />

Following her work at the union’s<br />

school, Cook opened her own ballet<br />

school. Like many rural teachers in<br />

this period, Cook travelled to reach<br />

students in nearby communities<br />

such as Garson, Copper Cliff, Elliot<br />

Lake, Espanola and Kapuskasing.<br />

She mounted recitals and directed<br />

an amateur concert group that gave<br />

performances in retirement homes,<br />

schools for mentally challenged<br />

students, and other community<br />

organizations.<br />

Her years with Volkoff fostered<br />

important friendships with dancers<br />

Don Gillies and Ruth Carse. She<br />

Members of the Volkoff Canadian Ballet in Boris Volkoff’s “Polovtsian Dances” from Prince Igor at the First Canadian Ballet Festival,<br />

Winnipeg, 1948<br />

Photo: Arthur Kushner<br />

No. 75, Fall 2015 5

Janet Baldwin Volkoff, Gweneth Lloyd and Boris Volkoff at the First Canadian Ballet Festival,<br />

Winnipeg, 1948<br />

performed in Gillies’s choreography<br />

for the Janet Baldwin Ballet and later<br />

brought him to set work on her own<br />

group in Sudbury. Her connection<br />

with Carse led to teaching opportunities<br />

in Edmonton with Carse’s<br />

newly formed Alberta Ballet. Cook<br />

was also an important team member<br />

in the initiative to start a dance<br />

program at Grant MacEwan College.<br />

Margaret Hample, Arnold Spohr and<br />

James Pape, May 31, 1948<br />

Cook made a career change in<br />

the 1980s when she began studies in<br />

theology ultimately being ordained<br />

as a United Church Minister in<br />

1984. During her<br />

years of ministry,<br />

she also<br />

choreographed<br />

liturgical dances.<br />

Her church<br />

work brought<br />

her to Manitoba<br />

and eventually<br />

retirement in<br />

Winnipeg where<br />

she assisted her<br />

dance colleagues<br />

in the archives at<br />

the Royal Winnipeg<br />

Ballet.<br />

Cook’s collection<br />

fills several<br />

gaps in the story<br />

of Canada’s<br />

burgeoning<br />

professional<br />

ballet scene of<br />

Barbara Cook<br />

Photo: Marcel Ray Photographers<br />

the mid-twentieth century giving<br />

us more details about Boris Volkoff,<br />

Janet Baldwin and Don Gillies.<br />

Lillian Lewis, May 31, 1948<br />

It also provokes more questions<br />

about the activities and connections<br />

between members of this generation.<br />

For example, a series of snapshots<br />

depicts members of the Winnipeg<br />

and Volkoff companies picnicking<br />

by the Port Credit River in Mississauga<br />

roughly a month after the<br />

First Canadian Ballet Festival.<br />

There are also rare items in the<br />

collection including Cook’s costume<br />

from Gillies’s acclaimed work<br />

I Want! I Want! for the Janet Baldwin<br />

Ballet, and photographer Arthur<br />

Kushner’s photos<br />

taken from the<br />

balcony of the<br />

Walker Theatre<br />

during the first<br />

Canadian Ballet<br />

Festival. I spoke<br />

to Kushner about<br />

his photos almost<br />

twenty years ago<br />

and he told me he<br />

had given them<br />

all away, mostly<br />

to Gweneth<br />

Lloyd. Lloyd’s<br />

photos from<br />

this period were<br />

sadly lost in the<br />

1954 fire that also<br />

destroyed her<br />

company’s documents,<br />

musical<br />

scores, costumes<br />

and sets. DCD now has some copies<br />

of these treasures from the past.<br />

6 Dance Collection Danse

Elizabeth<br />

Langley<br />

Embracing<br />

Transformation<br />

BY PHILIP SZPORER<br />

Elizabeth Langley is someone of limitless<br />

growth. Born in Melbourne, Australia, in 1933,<br />

she has been in Canada for fifty years – first<br />

teaching and directing performances, then<br />

founding the dance program at Concordia<br />

University. Not one to remain idle, she leads<br />

a rich life in post-retirement, performing as<br />

well as directing, providing dramaturgy and<br />

the coaching of dancers and choreographers.<br />

8 Dance Collection Danse

Call it the importance of being Elizabeth Langley.<br />

The octogenarian dancer-choreographer<br />

and educator has been variously described<br />

as a mentor, a teacher, an innovator … and an original,<br />

outspoken woman who can be brutally honest.<br />

Dancer-choreographer Denise Fujiwara worked with<br />

Langley for twenty years. She says she was exposed to,<br />

and benefitted from, the full force of Langley’s “many<br />

qualities that make her intimidating to work with: an<br />

incisive eye, a critical intelligence, an inability to lie about<br />

the work, a sophisticated aesthetic sense and an impatience,<br />

which means she does not suffer fools gladly.”<br />

Langley’s vision and discipline continues to influence<br />

Zelma Badu-Younge, professor of dance at Ohio University<br />

and a Concordia dance graduate. She’s deferential to<br />

her mentor’s “beauty, grace, power, strength, brilliance<br />

and a wealth of knowledge and intelligence. Such an<br />

engaging and creative spirit here on earth guiding, teaching<br />

and inspiring us all with honesty and pure heart.”<br />

Asked why she chose dance, Langley replies, “I don’t<br />

think I was supposed to be a dancer. But I’ve had a really<br />

good life, so I don’t feel badly about it. I think I was meant<br />

to be an actress.” Her sister, ten years older, had already<br />

“confiscated that performance mode.” Langley’s upbringing,<br />

like many Australian children, was very physical.<br />

“I had played every sport since I could stand on my two<br />

feet. And I used to do my ‘thing’. I didn’t even know a<br />

word to describe it at that point.” She’d dance and “interpret<br />

the music,” says Langley. “Then one of my brother’s<br />

girlfriends said to me, ‘Oh, I go to a studio where they<br />

do that.’ Now, the idea of people coming together to do<br />

my ‘thing’ was really exciting. So my mother took me<br />

to the [dance] studio.” The next week … she began.<br />

In 1951 Langley took a teacher’s course in creative<br />

dance. Two years later she was offered a job teaching<br />

adult and children’s dance classes. For seven<br />

years, she packed thirty-five to forty classes per week<br />

into her gruelling schedule, plus personal training,<br />

choreography and performing. “It was total absorption.<br />

I’d lie in bed at night bone-tired.” But she says,<br />

“If you can turn your passion into your profession,<br />

you’ll be one of the happiest people in the world.”<br />

She was married briefly, for one year, in 1958. “It was<br />

one of the things you did,” she says. 1960 was a turning<br />

point. Harry Belafonte’s company was touring Australia,<br />

and some of his musicians came to a friend’s party.<br />

She jokes that she was wearing a “horrible green and<br />

Top left: Elizabeth Langley teaching in Melbourne, Australia,<br />

late 1950s<br />

Bottom left: Elizabeth Langley, 1964<br />

Photo: Guenter Karkutt<br />

Top right: Elizabeth Langley rehearsing Angst, directed by<br />

Denis Faulkner for CBC television, 1974<br />

blue tartan ensemble.” Regardless, she met Belafonte’s<br />

accompanist Ernesto Calabria, and for the length of<br />

the tour they were “inseparable”. It was decided that<br />

Langley should join him in New York and become his<br />

common-law wife. Belafonte sponsored her student<br />

visa to attend the Martha Graham School. A letter dated<br />

October 10, 1960, written by Hanny Kolm Exiner, principal<br />

at the Studio of Creative Dancing, in Melbourne,<br />

supported her application. Langley, it states, has “intelligence,<br />

imagination, and great zest … She is a forceful<br />

dancer, with originality and a great sense of comedy.”<br />

She arrived in New York to a huge snowfall. Wading<br />

through snow banks, she made her way to Graham’s<br />

beautiful studios on East 63rd Street. She watched faculty<br />

class. “I said I am going to stay here until I know that,” she<br />

recalls. Even with all her experience, she was placed as a<br />

beginner. Graham told her, “You don’t even know how to<br />

breathe.” Langley gives a vivid description of the legendary<br />

Graham. “She was very short. Her body proportions<br />

were Asian, long spine and short legs. Her stacked<br />

hairstyle extended her height. At this stage she had a<br />

drinking problem, but she was an incredible genius.” She<br />

stayed with Graham five years. “What I loved about the<br />

Graham technique is that you danced from your gut to<br />

your fingertips and not from your fingertips to nowhere.”<br />

No. 75, Fall 2015 9

Tessa Hebb and Christopher House in<br />

Elizabeth Langley’s Anais Nin, Ottawa, June 1976<br />

Photo: Courtesy of Christopher House<br />

Politically and artistically, the city was a hotbed,<br />

though she didn’t meet up with the Judson Church artists.<br />

“In New York you can’t do everything. There was<br />

so much there, and I was starved.” But life in the city<br />

could last only so long with her student visa expiring,<br />

and she wasn’t looking for a serious dance career there.<br />

As for her relationship with Calabria, she says, “He<br />

wanted to get married. But you make your choices.”<br />

She boldly lit out from Second Avenue to a log<br />

cabin on Meech Lake. The year was 1965. In Ottawa,<br />

she says, “there seemed to be a lot of people waiting<br />

for somebody with energy to come and do<br />

things … [And] I came full of ideas and with a lot<br />

of toughness having survived in Manhattan.”<br />

A dress boutique she opened had difficulties<br />

and did not provide satisfaction. She<br />

rebounded as manager at the city’s noted Café<br />

Le Hibou Coffee House, where performers<br />

Josh White, Jr., Odetta, James Cotton and Bruce<br />

Cockburn headlined. While performing in a<br />

theatre piece at the space, in which she uttered<br />

only one line, she met a future husband, with<br />

whom she had a daughter. They later divorced.<br />

In the meantime, the Strathmere Farm<br />

summer day camp in North Gower, Ontario,<br />

hired her to teach dance to, says Langley, the<br />

“verbal, engaged and intelligent” children of<br />

activist parents. The experience prompted her<br />

to open a studio on Laurier Street. “I never<br />

forced a class plan on children, but I did on<br />

adults. I never wanted disciples. I wanted<br />

free spirits,” she says. Circa 1972 she was<br />

living and teaching at Ottawa’s Pestalozzi<br />

College, which wasn’t a college but an urban<br />

commune, with rent-affordable housing.<br />

Toronto Dance Theatre’s current artistic<br />

director, Christopher House, then a major in<br />

political science, was enrolled in her Movement<br />

for Actors course at the University of<br />

Ottawa in the fall of 1975. “I knew in the first<br />

class that I had encountered an extraordinary<br />

person,” he says. Within days, he was taking<br />

her evening sessions in modern dance at<br />

Pestalozzi. He describes her classes at U of O<br />

as “very inspiring, teaching us a new awareness<br />

of our bodies and unlocking sensations.”<br />

He quickly figured out what dancing meant<br />

to him, and how he moved most naturally. “I<br />

have a strong memory of a ritual we performed<br />

outside in a field, a hunt of sorts. At a certain<br />

point I started to run in a huge circle. The experience<br />

was utterly euphoric, and by the time I<br />

stopped running I was a different person.”<br />

Meanwhile Langley was exhausted and<br />

felt her practice did not have potential for growth. She<br />

booked tickets on a ship to New Zealand, where she<br />

had family and support. She was forty-five, poor and<br />

with a nine-year-old child. That’s when she received a<br />

phone call from Alfred Pinsky, the then dean of Fine<br />

Arts at Montreal’s Concordia University, offering her<br />

a job to first teach in the theatre department (a course<br />

called Dance Practicum) while designing a Canadian<br />

university dance degree program geared to training<br />

choreographers. It was a “top opportunity, in a city<br />

that I’d been told I would love.” Langley became the<br />

first chair of the Department of Modern Dance, inaugurated<br />

in the 1980/81 academic year and renamed<br />

10 Dance Collection Danse

Elizabeth Langley and James Tyler, “Improvisation”,<br />

Victoria School Gym, Montreal, 1980<br />

Photo: Ian Westbury<br />

the Department of Contemporary Dance in 1987.<br />

She had moved to Montreal late in 1978. “Some<br />

very heavy rumblings were happening here, artistically,<br />

politically and sociologically,” says Langley,<br />

referring to the game-changing election of the<br />

Parti Québécois two years earlier that saw masses<br />

of people leaving the province. “There was a passion<br />

here [after the PQ win]. Also, raw beginnings<br />

and disturbances are the most exciting of times.”<br />

The degree program was “one of the peak experiences<br />

of my life,” she says. “Everything that I had<br />

done [previously] prepared me for this job.” The<br />

small department started with her as the only fulltime<br />

faculty member and a roster of part-time teachers,<br />

including Silvy Panet-Raymond, who would<br />

become full-time faculty and Langley’s constant colleague<br />

throughout her tenure. The program required<br />

someone who was tough, but equally generous and<br />

supportive, to give leadership and feedback.<br />

Langley states in an unpublished transcript: “Some<br />

people when they first come to the department see me<br />

as a tyrant. Maybe it’s because I am very concerned<br />

with people learning how to work. I am of the idea<br />

that if you can do this you can always get work.” Langley<br />

inherited that ethic from her father. “He also had<br />

a philosophy, which I still live by, and it fits a day or<br />

a life span,” she says. “You wake in the morning – or<br />

you are born. You find out what you do best, and you<br />

do it the best you can. You do an honest day’s work<br />

for an honest day’s pay, and you deserve a dry bed<br />

and a warm meal at night, or a peaceful death.”<br />

The Concordia curriculum was devised to support the<br />

students’ development as original artists. Teachers did<br />

not teach their own method or choreograph on students.<br />

No. 75, Fall 2015 11

Elizabeth Langley (and her life-sized puppet) in her one-woman<br />

show in camera or not (translation “in private or not”), Montreal, 1998<br />

Photo: Steve Leroux<br />

In essence, the program supported the liberating power<br />

of the imagination. Year-end shows would include<br />

works by the students. “I really like four-minute works,”<br />

Langley indicates. “I think in four minutes you should<br />

be able to get on, make the statement you want to make,<br />

and get off. And I think that’s also good for the audience.<br />

Don’t hang around when the message has been spent.”<br />

A chapter entitled “Like Cactuses in the Desert:<br />

The Flourishing of Dance in Montréal Universities”<br />

in the book Renegade Bodies (DCD 2012), makes hay of<br />

Langley’s perceived outsider status in the Montreal<br />

dance community. Co-authors Dena Davida and Catherine<br />

Lavoie-Marcus write: “As a newcomer in the<br />

city and as a unilingual Anglophone, she worked in<br />

relative isolation from the others,” referring to Francophone<br />

counterparts from other university dance<br />

departments. Langley states, “Members of the community<br />

questioned my right to be here and do the<br />

job.” She adds, “Foreigners see things differently than<br />

local people, because we come and things are fresher<br />

to us, and I think we’re paying more attention.”<br />

Shortly after she arrived in the city, the Octobre en<br />

danse festival took flight. “I sat through every single<br />

program, and it was as though every dance company<br />

in this town was being promenaded in front of<br />

me.” The upsurge of rebellious dance experimenters<br />

in Quebec fascinated Langley. “There are always<br />

people doing something that other people are not<br />

doing. There’s faith in my heart about that forever and<br />

ever. This is why art keeps evolving; there’s always<br />

somebody that’s asking questions and creating.”<br />

During a sabbatical in 1997, she studied at Amsterdam’s<br />

School for New Dance Development. “I drifted so<br />

far from my desk. I didn’t know how I’d get back,” she<br />

says. She retired from her university job and jumped<br />

full throttle in re-establishing her performance life and<br />

12 Dance Collection Danse

the creation of her own one-woman shows. At a theatre<br />

festival in Turkey, Langley met Australian director Paul<br />

Rainsford Towner (known professionally as Rainsford),<br />

who heads an innovative company working in dance<br />

and physical theatre forms. Langley calls Rainsford “a<br />

visionary … a man that has an uncompromising desire<br />

to make theatre and a strength to create original work,<br />

and I see those things in me too.” Together they created<br />

Journal of Peddle Dreams, based on the writings and life of<br />

Australian author Eve Langley [a possible relation]. The<br />

emphasis was on getting to a stripped-down zone and<br />

making her presence felt. “He made me the best performer<br />

I had been in my life,” she says. “I got to the point<br />

where I was shameless, getting to the heart of things.”<br />

In a profession driven by the cult of youth and<br />

beauty, not to mention the physical demands of dance,<br />

Langley extends and defies the parameters of her<br />

domain. In 1999, she received the prestigious Jacqueline<br />

Lemieux Prize. The award committee described<br />

her as “an inspiration to the community who stretches<br />

the boundaries of the art form,” and praised her “command<br />

of the direction she has chosen to move in, and<br />

the strength and power with which she is doing it.”<br />

Post-retirement, Langley has also worked consistently<br />

as consultant, dramaturg and mentor for many artists.<br />

In late 2011, Toronto-based dancer-choreographer<br />

Sashar Zarif was re-imagining a lost dance form called<br />

mugham, which combines poetry, music and dance,<br />

and is connected to the Sufi and Shamanic cultures<br />

of Azerbaijan, Iran and Central Asia. “I’d heard Elizabeth<br />

was upfront and honest, and with her I’d get<br />

feedback. I wanted that. I didn’t need someone to<br />

pamper me.” They met at a dance studio. Zarif said,<br />

“I dance, you watch, we’ll talk.” As Langley recalls,<br />

“He took me into a world I didn’t know existed.” A<br />

month later, they started intensive work together.<br />

Crucial to Fujiwara was how Langley catalyzed<br />

her development as a choreographer and performer,<br />

helping her to navigate into “the arcane art<br />

of butoh and into the deep performance required for<br />

Natsu Nakajima’s solo Sumida River.” She admires<br />

Langley as a “deeply compassionate and a skilful<br />

communicator so that even in the most difficult<br />

times, she was always encouraging and inspiring.”<br />

Denise Fujiwara in Sumida River<br />

Photo: Cylla von Tiedemann, courtesy of Denise Fujiwara<br />

No. 75, Fall 2015 13

In 2011, Langley delivered the<br />

keynote address at the Society of<br />

Dance History Scholars’ international<br />

conference on dance<br />

dramaturgy in Toronto. She<br />

distilled advice in a compelling<br />

ten-point framework based on<br />

over thirty years of her experience.<br />

As Pil Hansen (with Darcey<br />

Callison and Bruce Barton) writes<br />

in “An Act of Rendering: Dance<br />

and Movement Dramaturgy”,<br />

Canadian Theatre Review, Summer<br />

2013: “Langley sees the<br />

dramaturg as mentor, a person<br />

who helps a choreographer reach<br />

clarity about his or her choreographic<br />

expression by responding<br />

to the emerging work from<br />

the position of an informed ‘first<br />

spectator.’ Langley operates from<br />

a neutral position, in which the<br />

dramaturg attempts to leave no<br />

artistic imprint on the work.”<br />

Zarif celebrates Langley’s seasoned<br />

perspective. “She’s become<br />

a big part of my life.” While House<br />

acknowledges, “She gave me lots<br />

of great advice that has stuck with<br />

me for forty years. I wouldn’t be<br />

a dancer or a choreographer if<br />

I hadn’t met her.” Badu-Younge<br />

comments that in her homeland<br />

of Ghana “there are many<br />

names in Ewe, the ethnic group<br />

of my father, to best describe<br />

[Langley’s] excellence: ‘Emefa’<br />

– Calmness, ‘Akorfa’ – Consoler,<br />

‘Dzigbodi’ – Patience, ‘Etriakor’<br />

– Undefeatable, and above<br />

all [she is] a ‘Kplorla’ – Leader.”<br />

Langley has always lived in the present and has<br />

never lost her enthusiasm or ability to embrace ambiguity<br />

and transformation. “She continues to remind<br />

people, through her own actions, how much one can<br />

love life, how to live in the present with courage and<br />

with a big open heart,” says Fujiwara. After sixty years<br />

in dance, Langley is not in a phase of career summation.<br />

By no means finished, she is in full “evolve and change”<br />

mode. “I’m designing myself a new life. I just don’t know<br />

quite what that is yet,” she says with a hearty laugh.<br />

Elizabeth Langley delivering the keynote address at Society<br />

of Dance History Scholars Conference, Toronto, 2011<br />

Philip Szporer, writer, lecturer and filmmaker teaches at Concordia<br />

University and is a scholar-in-residence at the Jacob’s Pillow Dance<br />

Festival. His dance writings have appeared in The Dance Current, Tanz<br />

and Hour, among others. He is co-founder, with Marlene Millar, of<br />

the arts film company Mouvement Perpétuel. Together they have<br />

co-directed and produced award-winning documentaries, short films<br />

and installation projects.<br />

14 Dance Collection Danse

Moving,<br />

in Tandem<br />

25 Years of Kaeja d’Dance<br />

BY SAMANTHA MEHRA<br />

If you haven’t heard the name Kaeja,<br />

prepare yourself: its nuances will<br />

exhaust you.<br />

Allen and Karen Kaeja have<br />

moved in synergetic tandem for twoand-a-half<br />

decades, infusing<br />

the name with many meanings.<br />

Kaeja means dancer. Kaeja means<br />

choreographer. Filmmaker. Archivist.<br />

Teacher. Lecturer. Writer. Festival<br />

Producer. Husband. Wife.<br />

16 Dance Collection Danse

Allen and Karen Kaeja, University of Toronto, 2013<br />

Photo: Zhenya Cerneacov<br />

The Kaejas, partners in art and in<br />

life, recently celebrated the twentyfifth<br />

anniversary of their Torontobased<br />

company, Kaeja d’Dance<br />

(formed in 1991), culminating in a<br />

performance as part of Harbourfront<br />

Centre’s NextSteps series. The<br />

evening captured the very essence<br />

of each half of the company. Karen’s<br />

Taxi! saw the cast of dancers take<br />

the audience on an emotional and<br />

kinesthetically engaging journey of<br />

the search for love, with an emphasis<br />

on relationships, sewing through<br />

provocative vignettes where costuming<br />

(including wedding gowns) and<br />

spoken text provide a vivid sensory<br />

experience. Allen’s .0 similarly<br />

considered the points at which<br />

human beings intersect, but using a<br />

distinctly athletic, physical, fastpaced<br />

vocabulary. While both were<br />

exploring the intricacies of human<br />

relationships, they did so with their<br />

signature kinesthetic voices under<br />

the umbrella of one evening.<br />

The Kaejas’s reservoir of collected<br />

performance programs and photography,<br />

along with their memories,<br />

are an archivist’s dream. This, as it<br />

turns out, is no accident; the importance<br />

of archiving in an effort to<br />

preserve history is of great import<br />

to both. “My father [Morton] was a<br />

Holocaust survivor, and when he left<br />

the camp he had no photographs,<br />

or anything else. When he came to<br />

Canada, whatever he could find from<br />

other people was gold, precious to<br />

him,” Allen Kaeja (born Allen Norris<br />

in Kitchener, Ontario, in 1959) says.<br />

“He kept his boat ticket, his train<br />

ticket, and other things so that his<br />

five children could have a history.”<br />

Understanding the importance of<br />

retaining artifacts, Allen began collecting<br />

personal items from a young<br />

age – anything that he considered a<br />

“part of his genetic makeup,” from<br />

his first wrestling award to his first<br />

dance program. Karen Kaeja (born<br />

Karen Resnick in Toronto in 1961),<br />

too, admits to having an instinct<br />

Allen Norris and Cynthia Hawkes in Norris’s Avari (1981)<br />

Photo: John Lauener<br />

to save, a deeply rooted part of her<br />

personality. “I began to keep everything<br />

because I started dancing<br />

late [at age eighteen], and I thought<br />

that becoming a performer would<br />

be a miracle. When I saw my name<br />

in print, it was a miracle realized,<br />

and [saving things] has been a<br />

continued fascination for me.”<br />

Both Kaejas began dance later<br />

in their lives, but the emergence of<br />

their craft coincided with exciting<br />

times in the Canadian dance fabric,<br />

worthy of remembering. Prior to<br />

dancing, Allen was submerged in<br />

the worlds of competitive wrestling<br />

and judo. At sixteen, he visited Israel,<br />

where he chanced upon a memorable<br />

dance experience in a bomb shelterturned-discothèque.<br />

“I found my<br />

dance that night, and it changed my<br />

life,” he remembers. “When I came<br />

back to Canada after six weeks, I<br />

felt my traditional western training<br />

was inadequate for me in terms of<br />

endurance, so two close friends and<br />

I would sneak into discos and start<br />

dancing. I danced so wildly no one<br />

would dance with me. If I cleared<br />

the dance floor, it was a good night.”<br />

This foray into dancing initially fell<br />

outside of his family’s understanding;<br />

admittedly, his father, a butcher,<br />

did not understand the arts. But<br />

after he attended the University of<br />

Waterloo and had been invited to<br />

No. 75, Fall 2015 17

Karen Resnick, age 10<br />

train in wrestling at an Olympic<br />

level, he considered ballet as a way<br />

to improve his balance and agility.<br />

He remembers walking into his first<br />

ballet class adorned in wrestling<br />

gear, where his teacher, Gabby<br />

Kamino, told him, “Lose the hoodie,<br />

lose the shoes and go stand at the<br />

barre.” After beginning to cull his<br />

technical skills, Allen’s first dance<br />

performance was as a super for<br />

The National Ballet of Canada’s The<br />

Sleeping Beauty in the fall of 1980.<br />

By the following year, he decided<br />

to dedicate his life solely to the arts<br />

and dance. This led him to enroll<br />

in a six-week summer program at<br />

York University, which sowed the<br />

seeds for his interest in site-specific<br />

work. Dance artist and instructor<br />

Terrill Maguire had her students<br />

explore the campus by performing<br />

site-specific pieces. In the fall of 1981,<br />

Allen auditioned for The School of<br />

the Toronto Dance Theatre (STDT),<br />

where he was accepted under probation.<br />

During the two years he was<br />

there, he felt more confident that he<br />

was, at his core, a choreographer<br />

even though he was still submerged<br />

in training. During his time at the<br />

school, he began cultivating a body<br />

of work and founded the Allen Norris<br />

Dance Theatre in 1982. Ever the<br />

rogue, he was admittedly evicted<br />

from STDT after stripping down<br />

onstage during a performance. But<br />

this moment did not signal an end<br />

to his relationship with STDT, but<br />

a beginning. “Within eight years<br />

[Karen and I] were both on faculty,<br />

teaching partnering, contact improvisation<br />

and our Kaeja Elevations.”<br />

Karen also entered dance later<br />

in life. Born to Devora and Arthur<br />

Resnick, Karen knew from a young<br />

age that she wanted to work in<br />

Allen Kaeja and Karen Kaeja in Allen’s Auro Choreola (1993)<br />

Photo: Cylla von Tiedemann<br />

the realm of psychology, but had<br />

similarly always carried a natural<br />

instinct to move. This innate desire<br />

eventually brought her to the halls<br />

of York University, where she would<br />

join the dance program, initially<br />

with an emphasis on dance therapy.<br />

“This was back in 1980, and I had<br />

no ballet training. I took a course<br />

at Toronto Dance Theatre (TDT) to<br />

figure out what modern dance was,<br />

too,” Karen recalls. She submerged<br />

herself in the rigours of ballet and<br />

contemporary dance training on<br />

a daily basis at York, while also<br />

minoring in psychology, and even<br />

started her own therapy practice,<br />

leading a dance therapy program<br />

at Baycrest Hospital (1982–1983) as<br />

part of a practicum for a York dance<br />

therapy course. But by this time, the<br />

performance bug had truly bitten<br />

her. Inspired by the dance professors<br />

and occasional guest artists at<br />

York (such as members of Toronto<br />

Independent Dance Enterprise), she<br />

18 Dance Collection Danse

Mairéad Filgate and Karen Kaeja in Allen Kaeja’s Armour/Amour (2011), Harbourfront Centre Theatre, Toronto<br />

Photo: Andréa de Keijzer<br />

submerged herself in more performance<br />

courses and workshops.<br />

These included a contact improvisation<br />

course offered by Sally Lyons,<br />

where Karen firmly “took a hold<br />

of the curiosity that followed me<br />

through a lifetime.” She was later<br />

featured in the works of choreographers<br />

such as Kathleen Rea, Peter<br />

Bingham and Randy Glynn.<br />

Allen and Karen collided in 1981<br />

during a choreographic process<br />

workshop to which Karen arrived<br />

late. “I saw this goddess walk into<br />

the studio, drifted over to her and<br />

started dancing with her,” Allen<br />

says. “It was because of Karen that<br />

I took my first contact class at TDT<br />

with [choreographer] Paula Ravitz,<br />

and we began to partner right away.”<br />

The meeting of the Kaejas was<br />

kinesthetic kismet, and no doubt<br />

resulted in their fascination with<br />

contact improvisation, site-specific<br />

works and their own branded<br />

contact movement technique, which<br />

they call “Elevations”. The process of<br />

understanding their own movement<br />

practices was born out of their first<br />

collaborations. Allen’s initial view<br />

of the body was based in wrestling<br />

and judo; yet, through their work<br />

together, they found a mutual<br />

understanding of each other’s bodily<br />

listening and responsiveness. “We<br />

never allowed ourselves to get<br />

complacent in our improvising.”<br />

In their years creating together,<br />

each have amassed a distinctive<br />

body of work, some of which have<br />

toured internationally and earned<br />

them many awards. As early as<br />

1990, they were creating their own<br />

site-specific work as a duo: Savage<br />

Garden, for instance, was created and<br />

performed by the pair, and moved<br />

vertically through the many levels<br />

of the Cecil Street Community<br />

Centre, and later became part of one<br />

of their first performance programs,<br />

Kinetically Charged (1991), at the<br />

Winchester Street Theatre. Karen<br />

initially acted as a muse and feature<br />

performer in Allen’s works, while<br />

also building her own choreographic<br />

voice. Seminal works for<br />

Karen, which explore identity and<br />

human relationships with provocative<br />

imagery, include Crave (2004)<br />

and Sarah (co-created with Allen in<br />

1994), which explores the identity<br />

of Morton Norris’s wife (whom he<br />

married prior to the Second World<br />

War) and toured across Canada.<br />

Karen’s Eugene Walks With Grace<br />

(1995), initially set on Allen and Eryn<br />

Dace Trudell, was remounted in<br />

2012 on Mairéad Filgate and Zhenya<br />

Cerneacov and became part of the<br />

Dusk Dances Ontario Tour in 2013.<br />

Allen’s work has often incorporated<br />

highly physical and athletic<br />

movement, while also at times<br />

exploring certain themes, such as the<br />

legacy of displacement and destruc-<br />

No. 75, Fall 2015 19

Karen Kaeja in a solo she created for Allen Kaeja’s Asylum of Spoons (2004)<br />

Photo: Albert Camicioli<br />

tion wreaked by war and the Holocaust,<br />

such as Old Country (1995) and<br />

Resistance (2000). Seminal multidisciplinary<br />

works for Allen also include<br />

Lost Innocence (1992/93), a work for<br />

five dancers and two actors exploring<br />

the events of a displaced youth<br />

being brought into the arms of the<br />

Children’s Aid Society, and Armour/<br />

Amour (2011), which takes a magnifying<br />

glass to the architecture of the<br />

body and of the self. Combined, the<br />

two artists have deconstructed much<br />

thematic and physical territory and<br />

have been able to reach out to and<br />

emotionally engage with international<br />

audiences through the universal<br />

nature of many of their works.<br />

Within the Kaejas’s body of work<br />

are a significant number of dance<br />

films, twenty-six to date. Allen began<br />

working with multimedia in the<br />

1980s and soon became interested in<br />

using the camera as the third dancer.<br />

Karen also investigated dance on<br />

film during a course run through<br />

the Dance Umbrella of Ontario. In<br />

the mid-1990s, the pair began to<br />

focus their mutual interest on the<br />

convergence of film and movement,<br />

adapting several of their stage works<br />

for the camera including Witnessed<br />

(1997), Old Country (appearing first<br />

as a duet for TVOntario in 1994 and<br />

then for CBC Television in 2004)<br />

and Asylum of Spoons (2005). Witnessed<br />

is adapted from the stage<br />

work Courtyard and explores the<br />

displacement of ghettoized individuals<br />

during WWII, hearkening back<br />

to Allen’s family history. Shot in<br />

only one day, and edited over a few<br />

weeks, it has toured internationally<br />

and is now part of the permanent<br />

collection at New York’s Museum<br />

of Modern Art. They also found<br />

Allen and Karen Kaeja in Allen’s Resistance (2000)<br />

Photo: Cylla von Tiedemann<br />

some revelations in exploring this<br />

medium on the performative level:<br />

“Underneath, I am a shy person,”<br />

Karen says. “Film suited my personality<br />

as it is a private encounter<br />

with a camera, but it allowed<br />

me to communicate to many.”<br />

The Kaejas have also continued to<br />

make site-specific and audienceengaging<br />

performances a central<br />

aspect of their annual work. As early<br />

as 1987, they embarked on a multidisciplinary<br />

work titled Beare: a Celtic<br />

Odyssey, involving seven performers<br />

at the Winchester Street Theatre with<br />

live music by Loreena McKennitt and<br />

script by Allen. More recently, they<br />

have performed as part of Toronto’s<br />

Nuit Blanche. In Stable Dances (2008),<br />

they sourced from a previous<br />

site-specific work (Bird’s Eye View) to<br />

create an all-night installation in the<br />

historic stables and carriage rooms of<br />

Casa Loma for a revolving audience,<br />

incorporating live video projections,<br />

with music by Edgardo Moreno and<br />

over twenty performers. They are<br />

also the masterminds behind annual<br />

outdoor community events such as<br />

Porch View Dances.<br />

The Kaejas are prolific teachers<br />

in the Toronto dance community<br />

and beyond. Indeed, their teaching<br />

20 Dance Collection Danse

contracts with the Scarborough and<br />

Peel Boards of Education in the 1990s<br />

funded their initial concerts. Their<br />

goal has been to build communities<br />

while also encouraging risk-taking,<br />

kinesthetic understanding and confidence<br />

in dancers and non-dancers<br />

alike. Through improvisational<br />

structures, the Kaejas allow for<br />

movers to experience sharing weight<br />

and working with momentum. In<br />

addition to mentoring students at<br />

STDT, Canada’s National Ballet<br />

School and the Canadian Children’s<br />

Dance Theatre (now Canadian Contemporary<br />

Dance Theatre, CCDT),<br />

they have taught in the public school<br />

sector. The fun has been in seeing<br />

movers transform before their eyes.<br />

“Karen and I worked with CCDT,<br />

and we got a nine-year-old to be<br />

able to take me on her shoulder; it<br />

changed her life and instilled in her<br />

a kinetic understanding of being<br />

powerful,” says Allen. “Partnering<br />

is universal; if we can give you the<br />

foundation, the world is yours.”<br />

DCD co-founder Lawrence Adams<br />

coined the title of another Kaeja<br />

creation, a teaching syllabus for<br />

schools called Express Dance made<br />

in collaboration with drama teacher<br />

Carol Oriold, and published by DCD<br />

in 2000. The syllabus crystallized<br />

as an idea after Oriold requested a<br />

handout following a 1998 workshop<br />

at the Council of Ontario Drama<br />

and Dance Educators conference.<br />

A primer for teachers, it incorporates<br />

compositional frameworks<br />

and movement lexicons, engaging<br />

students from grades four to twelve<br />

in a co-operative and creative movement<br />

space. After Oriold shadowed<br />

the Kaejas for over a year at various<br />

teaching events, she compiled the<br />

notes, which were then edited down<br />

by Allen and Adams into a now<br />

frequently used publication. Indeed,<br />

this primer set a tone for movement<br />

creation that reached beyond the<br />

classroom and into the Kaejas’s own<br />

processes. Their interest in educating<br />

translates into the emerging artist<br />

world as well. The pair created a second<br />

company, K d’D2 (2000–2005),<br />

which offered graduates from dance<br />

conservatory programs (such as<br />

STDT and CCDT) the opportunity<br />

to begin dancing in professional<br />

works, such as Allen’s Resistance,<br />

and tour Ontario. These tours also<br />

offered the dancers the opportunity<br />

to engage with new communities,<br />

develop relationships and teach.<br />

Both Allen and Karen have also<br />

helped to nurture the festival culture<br />

for dance in Canada. Estrogen, a<br />

festival for women creators, was<br />

co-founded by Karen and Sylvie<br />

Bouchard. Karen also co-founded<br />

The Festival of Interactive Physics<br />

(with Pam Johnson), which ran for<br />

ten years and invited luminaries<br />

of North American contemporary<br />

improvisation, such as Andrew<br />

Harwood, Nancy Stark Smith and<br />

Peter Ryan, to conduct workshops<br />

Zhenya Cerneacov, Merideth Plumb, Ana Claudette Groppler, Michael Caldwell and Allen Kaeja in Karen Kaeja’s Taxi! (2015),<br />

Harbourfront Centre Theatre, Toronto<br />

Photo: Ken Ewen<br />

No. 75, Fall 2015 21

Karen and Allen Kaeja in Allen’s X-ODUS (2013),<br />

Harbourfront Centre Theatre, Toronto<br />

Photo: Ken Ewen<br />

for over thirty participants. In his<br />

own right, Allen co-founded the<br />

CanAsian Dance Festival (1996) with<br />

Denise Fujiwara after being asked<br />

to help coordinate the dance portion<br />

of Asian Heritage Month. “[Denise]<br />

was as passionate as I was,” he<br />

says. “We felt the community was<br />

in such a rich place, moving forward<br />

in many contemporary ways.<br />

We wanted to promote and assist<br />

the aesthetic.” Prior to this, Allen<br />

co-founded fFIDA (fringe Festival<br />

of Independent Dance Artists) in<br />

1991 with Michael Menegon. During<br />

its run, fFIDA was a successful<br />

vehicle for independent dance<br />

artists from Canada and beyond to<br />

plant their feet in the dance milieu<br />

22 Dance Collection Danse<br />

and produce their own shows.<br />

The duo continues to prolifically<br />

perform and create, in addition to<br />

presenting at conferences and serving<br />

as artists in residence across<br />

the country. Most recently, they<br />

performed in lifeDUETS, a commissioned<br />

series for the pair that, in<br />

its various incarnations, has taken<br />

them on tours across Canada, to<br />

Mexico, Europe and Asia. In October<br />

of 2015, they commissioned<br />

choreographers Tedd Robinson<br />

and Benjamin Kamino to make<br />

works that challenged their “more<br />

current bodies”. This challenge<br />

has also seen them involved with<br />

Older & Reckless, a series featuring<br />

senior artists and founded by<br />

Claudia Moore, artistic director<br />

of MOonhORsE Dance Theatre.<br />

After cultivating such a diverse<br />

and relentless repertoire of projects<br />

for well over two decades,<br />

raising two daughters and working<br />

in beautiful synergy, one has<br />

to ask: what’s next for the Kaejas?<br />

“Sky-diving,” says Karen. “That<br />

is what we do as artists; we take<br />

the plunge, and it stimulates us.”<br />

Samantha Mehra Donaldson (MA) is a professional<br />

researcher and historian with an<br />

emphasis on media, dance history and heritage.<br />

She has contributed to Dance Collection<br />

Danse Magazine, The Dance Current, The<br />

Canadian Encyclopedia Online and The Oxford<br />

Forum for Modern Language Studies.

No. 75, Fall 2015 23

Finding Mrs. Colville<br />

WWI Patriotic Performances<br />

in St. John’s<br />

BY AMY BOWRING<br />

Newfoundland has been the<br />

home of my maternal and<br />

paternal ancestors for over 200<br />

years. Its theatrical dance heritage<br />

has been a fascination of mine,<br />

and various research trips over the<br />

years have revealed the early echoes<br />

of theatrical dance in St. John’s in<br />

the twentieth century, as well as<br />

the later achievements of those<br />

who followed. It is a dance story<br />

that both reflects other patterns in<br />

Canadian dance history and that<br />

also etches its own distinct path.<br />

July 1, 2016 is an important date<br />

for the people of Newfoundland.<br />

It marks the 100th anniversary of<br />

the start of the Battle of the Somme.<br />

There, on that first day of July in 1916,<br />

at 9:15 a.m., 778 men of the Newfoundland<br />

Regiment went over the<br />

tops of their trenches near the French<br />

village of Beaumont-Hamel to attack<br />

the Germans. When the next roll<br />

Mr. Leonard Reid, Miss Mary Doyle, Miss Bartlett, Miss Lois<br />

Reid, Mrs. Helen Colville and Miss Flora Clift (sitting down)<br />

in Mrs. Colville’s Triumph of Harlequin, 1915<br />

call was taken, 68 men answered<br />

their names – 386 were wounded;<br />

324 were dead or missing and<br />

presumed dead. It was a defining<br />

moment for this small country. Even<br />

after Confederation with Canada<br />

in 1949, July 1 for Newfoundlanders<br />

has never been so much Canada<br />

Day as it is Memorial Day. Knowing<br />

the significant military sacrifices<br />

made by Newfoundland during the<br />

Great War, and knowing the prominence<br />

of patriotic performances<br />

to raise funds for the war effort in<br />

other parts of Canada, I became<br />

curious to know what Newfoundlanders,<br />

and specifically women<br />

in St. John’s, were doing in terms<br />

of performances for benevolent<br />

purposes during World War I. And<br />

that’s when I found Mrs. Colville …<br />

In the Dance Collection Danse<br />

archives, there are photocopies of a<br />

handful of pages from a 1916 publication<br />

called The<br />

Distaff produced by<br />

the Women’s Patriotic<br />

Association of Newfoundland.<br />

An article<br />

about amateur theatricals<br />

includes two<br />

references to a Mrs.<br />

Colville and includes<br />

two photographs of<br />

her productions: The<br />

Triumph of Harlequin<br />

and a pastoral play<br />

held at Vigornia,<br />

Cover page of the 1916 edition of The<br />

Distaff published by the Women’s Patriotic<br />

Association<br />

which was the estate of St. John’s<br />

bakery owner John Browning. With<br />

the help of archivists and digital<br />

sources at the Centre for Newfoundland<br />

Studies at Memorial University,<br />

Mrs. Colville’s contribution, and<br />

that of others, began to unfold.<br />

Born Helen Withers in the early<br />

1890s, Mrs. Colville was the daughter<br />

of John and Emma Withers;<br />

Withers had become the King’s<br />

Printer in St. John’s in 1890, replacing<br />

his own father in this role. As a<br />

member of the Church of England,<br />

young Miss Withers would have<br />

been educated at Bishop Spencer<br />

College in Newfoundland’s<br />

church-run school system. By the<br />

late 1890s, Bishop Spencer College<br />

had a reputation for offering<br />

a wide variety of extra-curricular<br />

activities including dramatics.<br />

24 Dance Collection Danse

Numerous news paper clippings<br />

demonstrate that Helen Withers<br />

had a keen interest in performance;<br />

one of the earliest clippings found<br />

shows that she was in the cast of a<br />

production of C.M.S. McLellan’s<br />

Leah Kleschna at the Total Abstinence<br />

Hall (T.A. Hall) in January 1909. And<br />

in the following month, she was in<br />

a comedietta called Mrs. Oakley’s<br />

Telephone at the British Hall and a<br />

production of the one-act farce My<br />

Lord In Livery at the Synod Hall.<br />

She was back at the T.A. Hall in<br />

April in the play Liberty Hall. 1910<br />

saw our Miss Withers in a “Grand<br />

Variety Entertainment” at the Canon<br />

Wood Hall where the audience took<br />

in songs, dances and a playlet.<br />

In the spring and fall of 1911,<br />

Helen Withers performed in benefit<br />

concerts for the Feild-Spencer<br />

Association in aid of these two<br />

Church of England schools: Bishop<br />

Feild for boys and Bishop Spencer<br />

for girls. On both occasions,<br />

she appears to have sung a duet<br />

with a young man named Cecil<br />

Clift. On February 14, 1912, she<br />

performed in a one-act comedy at<br />

a Valentine Social for the Imperial<br />

Order Daughters of the Empire at<br />

the Methodist College Hall. This<br />

comedy was followed by a “Japanese<br />

dance” and then a tableau. And in<br />

the same evening, she performed a<br />

Pierrot dance with Clift at another<br />

Valentine benefit, which “scored a<br />

great success” with the audience<br />

according to the Evening Telegram.<br />

In October 1910, Helen Withers<br />

and many other single society girls<br />

were invited to a ball at Government<br />

House to entertain the naval cadets<br />

of the HMS Cornwall. It is quite<br />

possible that it was here that she met<br />

her future husband, Lieut. Mansel<br />

Colville, as he was assigned to the<br />

Cornwall. Colville, himself, had trod<br />

the boards in A Pantomime Rehearsal<br />

at the T.A. Hall in 1909. The two were<br />

married on September 11, 1913. Serving<br />

in the Royal Navy would have<br />

Lady Davidson as<br />

depicted in The<br />

Distaff, 1916<br />

taken the lieutenant<br />

away from home<br />

for much of the<br />

year particularly<br />

as the possibility<br />

of war increased.<br />

Eleven months after<br />

their marriage,<br />

Britain declared<br />

war on Germany<br />

on August 4, 1914<br />

and the call for volunteers soon<br />

went out across Newfoundland.<br />

The women on the home front<br />

also got to work right away. An early<br />

“Patriotic Concert” in St. John’s, if not<br />

the first, was given on September 29,<br />

1914. It was organized by the Women’s<br />

Patriotic Association, which was<br />

tremendously productive throughout<br />

the war with fundraising,<br />

making bandages and organizing<br />

women to knit socks and other items<br />

of comfort for the men overseas.<br />

Through much of the war, they<br />

were led by Lady Davidson, the<br />

governor’s wife, and she often<br />

opened up Government House as a<br />

centre for the association’s labours.<br />

This particular benefit concert was<br />

held at the Casino, a local vaudeville<br />

and movie house that often hosted<br />

patriotic performances during the<br />

war and was located on the second<br />

floor of the T.A. Hall. In addition to<br />

a number of patriotic songs, such<br />

as the Marseillaise and the Russian<br />

national anthem, a group of national<br />

dances of the United Kingdom were<br />

presented. The latter half of the<br />

program was dedicated to a series<br />

of seven tableaux vivants with titles<br />

such as “Newfoundland’s Offering”,<br />

“The Hero of the Hour”, “The<br />

Allies” and “The British Empire”.<br />

The term “tableaux vivants”<br />

translates to mean “living pictures”.<br />

Costumed performers posed in<br />

an arrangement that depicted a<br />

scene, or living picture, and then<br />

they moved to transition into a new<br />

picture. In patriotic performances<br />

using tableaux, the personification<br />

of nations was quite common.<br />

Tableaux were a widespread form of<br />

entertainment with roots in the royal<br />

pageants of the early Renaissance.<br />

The tableaux of the late nineteenth<br />

and early twentieth centuries,<br />

often performed by refined young<br />

ladies – and sometimes gentlemen,<br />

are more connected to “Delsartean<br />

Expression” developed by French<br />

music and drama educator François<br />

Delsarte. Delsarte approached<br />

drama education from a scientific<br />

and analytical perspective. He saw<br />

human experience as physical,<br />

mental and emotional-spiritual, and<br />

he divided the body into parts that<br />

corresponded to these distinctions.<br />

Examples of Delsartean expression<br />

for “watching” and “ridicule”<br />

No. 75, Fall 2015 25

Members of the Rossley Kiddie Company, St. John’s, 1917. These costumes provide a good indication of the personification of nations<br />

that was typical in patriotic tableaux.<br />

Photo courtesy of the Rossley Kiddie Company Collection (COLL-472, 1.01.007), Archives and Special Collections, Memorial Libraries<br />

He created a rather elaborate system<br />

determining how certain body parts<br />

should be used to communicate<br />

specific emotions and behaviours.<br />

Delsarte’s methods were introduced<br />

to America in the 1870s by<br />

an actor and teacher named Steele<br />

MacKaye who had studied with<br />

Delsarte in France; one of MacKaye’s<br />

students, Genevieve Stebbins,<br />

also helped to spread Delsarte’s<br />

teachings in New York and Boston.<br />

Considering that the routes of many<br />

of the Newfoundland steamship<br />

companies connect St. John’s to<br />

Halifax, New York and Boston, it<br />

is easy to imagine how Delsartean<br />

Expression and its use in tableaux<br />

could influence performances in St.<br />

John’s. There are several accounts<br />

of tableaux in St. John’s dating back<br />

to the 1890s as entertainment, as a<br />

diversion at school assemblies, or as<br />

performances in aid of organizations<br />

such as the Church Lads’ Brigade.<br />

The records of patriotic performances<br />

uncovered in this research<br />

reveal that Mrs. Colville participated<br />

in twenty-nine out of thirty-five<br />

shows over the course of the war<br />

and we know she missed some<br />

shows because she was in the U.K.<br />

She was variously a performer,<br />

organizer, director and choreographer,<br />

and she often worked with<br />

Mrs. Herbert Outerbridge and Mrs.<br />

Chater. Participants in many of these<br />

concerts include names of old and<br />

affluent St. John’s families such as<br />

Outerbridge, Clift, Reid, Rendell,<br />

Ayre, Job, LeMessurier, Bowring,<br />

Baird and Harvey, as well as wellknown<br />

artistic families such as<br />

Charles Hutton and the Rossleys.<br />

John and Adelaide Browning also<br />

played an important role in patriotic<br />

work through organizational efforts<br />

and through their estate, Vigornia.<br />

The Brownings provided the estate<br />

grounds for several garden fêtes<br />

and patriotic performances to raise<br />

funds for charitable war work. Mrs.<br />

Browning also opened her doors two<br />

or three afternoons per week for the<br />

members of the Women’s Patriotic<br />

Association (WPA) to do their work.<br />

In November 1917, Mrs. Browning<br />

returned from a trip to Canada (a<br />

separate country from Newfoundland<br />

at the time) where she had met<br />

doctors and nurses with experience<br />

in treating consumption. One of her<br />

particular causes was Jensen Camp,<br />

which had been created primarily<br />

on her initiative in 1916 as a hospital<br />

for soldiers with tuberculosis. The<br />

Evening Telegram on June 11, 1918<br />

reported the status of fundraising<br />

for Jensen Camp and listed Mrs.<br />

Colville’s contribution from the<br />

proceeds of patriotic performances<br />

at $410. In 1918, Mrs. Browning<br />

was made an officer of the Order<br />

of the British Empire for her work<br />

with the WPA and Jensen Camp.<br />

Vigornia was situated on King’s<br />

Bridge Road where<br />

the Family Court<br />

now resides. A successful<br />

garden fête<br />

was held on July 14,<br />

1915 and this may<br />

be the first of such<br />

activity at Vigornia.<br />

It was held under<br />

the patronage<br />

of the Governor<br />

Mrs. Adelaide<br />

Browning as<br />

depicted in The<br />

Distaff, 1916<br />

26 Dance Collection Danse

Back row: Miss Agnes Hayward, Miss<br />

Bradshaw, Mrs. Babcock, Mrs. Colville,<br />

Mrs. Chater, Miss Rendell; Front row:<br />

Miss Doyle, Miss Ayre (Cupid), Mrs. H.<br />

Outerbridge, Miss Job and Miss Flora Clift<br />

(reclining) in On Zephyr’s Wings, 1915<br />

and Lady Davidson in aid of cots<br />

for the wounded, though by this<br />

time in the war the Newfoundland<br />

Regiment was primarily training<br />

in the U.K. The St. John’s Daily Star<br />

described the pleasant setting:<br />

“Vigornia is always attractive but<br />

yesterday it seemed as if some fairy<br />

wand had touched the place.”<br />

The main attraction of the day was<br />

the pastoral play On Zephyr’s Wings.<br />

Mrs. Colville played the role of<br />

“Alidor” while her frequent collaborators,<br />

Mrs. Chater (also the director)<br />

and Mrs. Outerbridge, played<br />

“Gracieuse, the Queen’s Daughter”<br />

and “Queen Ilerie” respectively. Miss<br />

Flora Clift, who was also in nearly<br />

every production with Mrs. Colville,<br />

played “Zephyr, Goddess of the West<br />

Wind”. The show was set on a terrace<br />

surrounded by trees and the Daily<br />

Star had much praise for the<br />

production: “The dancing was<br />

perfect, even Terpsichore would have<br />

been envious and the music<br />

delighted all. The costumes – everything<br />

of the pastorale was as the<br />

author intended it should be.”<br />

Further funds were raised through<br />

the sale of candy, flowers and fancy<br />

work. The event was such a success<br />

that it was repeated at Vigornia on<br />

July 26 and the two occasions<br />

combined raised over $600.<br />

It’s important to note that such<br />

performances served more than<br />

just fundraising purposes – they<br />

were also important to local morale<br />

and recruiting, particularly as the<br />

fighting wore on and casualty lists<br />

grew longer. The July 27, 1915 edition<br />

of the Daily Star described the event<br />

at Vigornia as “a scene that one was<br />

loathe to leave.” And an account of<br />

On Zephyr’s Wings in the Evening<br />

Telegram on July 24, 1915, indicates<br />

the power of escape people needed:<br />

The fairy’s wand will again turn<br />

shepherds into princes, shepherd esses<br />

will dance upon the sward, while<br />

Cupid flits among the trees and<br />

wields its magic dart. Mordicante<br />

with her fairies and her gnomes<br />

bringing discord will draw her magic<br />

circle round fair Gracieuse, but<br />

Zephyr’s lightest breath will break<br />

the spell, and Love reign over all.<br />

A patriotic tableau vivant on a float in the Peace Parade, August 1919<br />

This plotline could easily exist as a<br />

metaphor for the war itself with the<br />

malevolent Mordicante representing<br />

the Germans and Zephyr, the<br />

Allies – in the end, love and peace<br />

will reign supreme and the sons<br />

of Newfoundland will return.<br />

An ad for the Casino Theatre on<br />

January 30, 1918 further highlights<br />

the role performance can play in the<br />

war effort, stating: “The machine<br />

that wins the war through fighting<br />

or through industry is the human<br />

brain. And what the brain requires<br />

the theatre gives – change of thought,<br />

relaxation, the real rest that makes<br />

the brain better fit for work next day.”<br />

While one should take the marketing<br />

spin of such a statement into<br />

consideration, there is a lot to be said<br />

for the Casino Theatre’s argument.<br />

A particularly grand event was<br />

held at Vigornia on August 2, 1917.<br />

Called the “Sunshine Entertainment”<br />

it was organized by Mrs.<br />

Charles McKay Harvey. By this time,<br />

the Newfoundland Regiment had<br />

played a significant role in major battles:<br />

Gallipoli (September 1915–January<br />

1916), Beaumont-Hamel (July<br />

1916), Guedecourt (October 1916)<br />

and Monchy-le-Preux (April 1917),<br />

and the work of women on the home<br />

front was more necessary than ever.<br />

Once again the grounds of<br />

Vigornia were decked out in bunting,<br />

with the addition of electric<br />

lights during the evening. The<br />

gardens were in full bloom and there<br />

were decorated stalls where sweets,<br />

ice cream, flowers and handmade<br />

items were sold. The afternoon<br />

performance opened with a dance<br />

of the seasons followed by a minuet.<br />

The press gave great acclaim to Mrs.<br />

Colville and Miss Flora Clift for<br />

their Narcissus and the Nymph dance.<br />

Mrs. Colville choreographed the<br />

movement to a mazurka by Auguste<br />

Durand, and the pool that Narcissus<br />

No. 75, Fall 2015 27

gazes into was created using an<br />

arrangement of mirrors and grass.<br />

The evening show presented a<br />

series of tableaux vivants, which,<br />

according to the Daily Star, “surpassed<br />

anything ever<br />

seen here and was equal<br />

to anything ever seen<br />

abroad on the same<br />

scale.” The first tableau<br />

paid tribute to the newest<br />

ally, the United States,<br />

which had joined the<br />

war just a few months<br />

earlier in April 1917. Mrs.<br />

Colville represented<br />

France and several other<br />

performers personified<br />

other allies: Belgium,<br />

Russia, Italy, Serbia,<br />

Canada, Britannia,<br />

India, Newfoundland<br />

and Greece. Another<br />

interesting tableau was<br />

called “Women Before<br />

and During the War”.<br />

In the “before” section,<br />

performers portrayed a<br />

lady and her maid, suffragettes<br />

and an actress.<br />

During the war, these<br />

characters transform into<br />

lady farmers, munitions<br />

workers and nurses.<br />

Social dancing followed<br />

the performance and<br />

the whole event raised<br />

$1170 for Jensen Camp.<br />

By February 1918,<br />

Mrs. Colville was advertising in<br />

the Evening Telegram for an experienced<br />

nurse to look after a young<br />

child. When exactly her child was<br />

born is unknown but it is highly<br />

likely that she performed the<br />

Sunshine Entertainment while<br />

pregnant – a bold and independent<br />

move for a woman of the time.<br />

The Brownings hosted another<br />

garden fête at Vigornia a year later<br />

that included games and an open<br />

air concert in the afternoon, tableaux<br />

vivants in the evening and<br />

social dancing until midnight.<br />

Among the afternoon games was<br />

Front cover of the instruction manual for the tableau and flag drill Rule<br />

Britannia, performed in St. John’s in 1917<br />

one called “Kill the Kaiser”. The<br />

first series of nine tableaux depicts<br />

familiar stories such as Blue Beard,<br />

Pocahontas and Cinderella. The<br />

next nine tableaux were patriotic in<br />

nature with titles such as “After the<br />

Battle”, “The Red Cross” and “Britannia<br />

Calls Her Sons”. Mrs. Colville<br />

portrayed Belgium in a tableau<br />

with her daughter, and her friend<br />

Mrs. Outerbridge played Britannia<br />

in several scenes. This time, $1121<br />

was raised for Jensen Camp.<br />

Tableaux vivants made a last<br />

patriotic appearance in the St. John’s<br />

Peace Parade in August 1919.<br />

Several of the parade<br />

floats included tableaux<br />

paying tribute to the<br />

other allied nations. Mrs.<br />