ERADICATION OF GUINEA WORM DISEASE

1VIcLdr

1VIcLdr

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>ERADICATION</strong> <strong>OF</strong><br />

<strong>GUINEA</strong> <strong>WORM</strong> <strong>DISEASE</strong><br />

Case Statement

Since The Carter Center began leading global Guinea worm disease eradication efforts in 1986 together with<br />

endemic countries and the World Health Organization, as well as other trusted partners such as UNICEF, the<br />

campaign has reduced the number of cases 99.99 percent, from 3.5 million cases annually in Africa and Asia to<br />

22 cases in 2015.<br />

Guinea worm eradication is drawing ever closer to the finish line. The campaign demonstrates what remarkable<br />

change can occur with full engagement — from national ministries of health and each individual in affected<br />

villages — even though there is no drug to cure Guinea worm disease or a vaccine to prevent it.<br />

Each country that triumphs over Guinea worm disease serves as a reminder to the world that the greatest<br />

challenges can be overcome with hard work, political commitment, and support of the international community.<br />

However, success in global eradication will require stronger commitment of the four endemic countries fighting<br />

the remaining cases, as well as of international partners in this public health initiative.<br />

Everyone has a stake in these efforts. The entire world stands to gain from the eradication of Guinea worm disease,<br />

not only because an age-old affliction will have been wiped off the surface of the planet, but also as proof that<br />

eradication can be achieved with willpower, political involvement, local perseverance, and financial investment.<br />

It was done with smallpox, and we can do it again.<br />

We urge development partners — governments, foundations, and corporations — to generously contribute financial<br />

support in a united demonstration that, together, we can ensure the eradication of Guinea worm disease by 2020.<br />

With best wishes,<br />

Jimmy Carter<br />

Former U.S. President<br />

Co-founder, The Carter Center<br />

Margaret Chan<br />

Director-General<br />

World Health Organization<br />

Boys with Guinea worm disease receive treatment at a case containment center in South Sudan.<br />

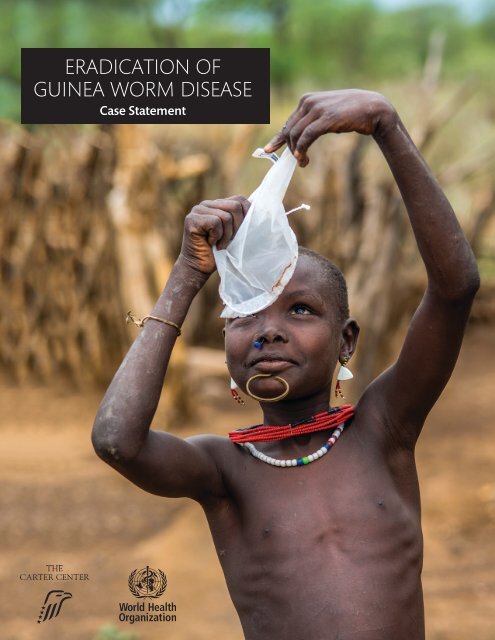

On the cover: A South Sudanese boy examines a cloth filter. Filtration of drinking water prevents Guinea worm disease.

ABOUT <strong>GUINEA</strong><br />

<strong>WORM</strong> <strong>DISEASE</strong><br />

Guinea worm disease is an affliction of<br />

2011<br />

poverty, debilitating residents of remote<br />

COTE GHANA<br />

D’IVOIRE 2015<br />

and marginalized communities in sub-<br />

2013<br />

Saharan Africa. A painful and incapacitating<br />

TOGO BENIN 2009<br />

waterborne disease, it negatively affects health,<br />

2011<br />

agricultural productivity, school attendance, and<br />

overall quality of life in the communities where<br />

it is found. 1 Guinea worm disease is caused by<br />

the parasitic worm Dracunculus medinensis, which<br />

infects people who drink water from stagnant<br />

sources containing microscopic infective larvae<br />

harbored by tiny copepods (“water fleas”). During<br />

the yearlong incubation period, individuals do<br />

not know they are infected and become unwitting<br />

carriers of the parasite until the adult female worms,<br />

measuring up to one meter in length, emerge. An<br />

emerging worm causes a blister on the victim’s skin,<br />

accompanied by a severe burning sensation and<br />

pain, followed by an open lesion with a protruding<br />

Guinea worm. When a patient cools the wound in<br />

a stagnant water source, the worm releases hundreds<br />

1989<br />

1990<br />

of thousands of larvae, which are readily ingested<br />

1991<br />

by copepods, contaminating the water source and<br />

1992<br />

continuing the transmission cycle.<br />

There is no drug to cure Guinea worm<br />

disease or vaccine to prevent it, humans do<br />

not develop immunity to the disease, and<br />

there is no known wild animal reservoir from<br />

which the disease can return to humans once<br />

transmission is interrupted. However, disease<br />

transmission can be prevented. The Carter<br />

Center — in partnership with the national Guinea<br />

worm eradication programs of the ministries of<br />

health of affected countries, the World Health<br />

Organization (WHO), and strategic partners such<br />

as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention<br />

and UNICEF — have pioneered community-based<br />

responses to prevent transmission, and ultimately<br />

eradicate Guinea worm disease by 2020.<br />

MAURITANIA<br />

2009 MALI<br />

NIGER<br />

5<br />

CHAD SUDAN<br />

SENEGAL<br />

2013<br />

9<br />

YEMEN<br />

2002<br />

2004<br />

2004<br />

BURKINA FASO<br />

NIGERIA<br />

CENTRAL AFRICAN<br />

2013 REPUBLIC SOUTH ETHIOPIA<br />

2007 SUDAN 3<br />

CAMEROON<br />

5<br />

2007<br />

UGANDA<br />

2009 KENYA<br />

1994<br />

1993<br />

1994<br />

1995<br />

1996<br />

1997<br />

1998<br />

1999<br />

2000<br />

2001<br />

2002<br />

2003<br />

2004<br />

2005<br />

2006<br />

2007<br />

2008<br />

2009<br />

2010<br />

2011<br />

2012<br />

2013<br />

2014<br />

2015<br />

77,863<br />

78,557<br />

164,977<br />

129,852<br />

96,293<br />

75,223<br />

63,718<br />

54,638<br />

32,193<br />

16,026<br />

10,674<br />

25,217<br />

9,585<br />

4,619<br />

3,190<br />

1,797<br />

1,058<br />

542<br />

148<br />

126<br />

22<br />

152,814<br />

229,773<br />

374,202<br />

543,585<br />

623,579<br />

PAKISTAN<br />

1996<br />

Progress on Guinea<br />

worm eradication since<br />

1986, by country<br />

Year Certified by<br />

WHO as Free of<br />

Guinea Worm Disease<br />

Year Guinea Worm<br />

Transmission Halted<br />

Cases Remaining<br />

at End of 2015<br />

(provisional count)<br />

Annual number of cases of Guinea worm disease worldwide since 1989<br />

892,055<br />

INDIA<br />

2000<br />

3

Because Guinea worm is a<br />

waterborne disease, water<br />

filtration can prevent its spread.<br />

THE NEEDS<br />

In 1986, an estimated 3.5 million cases of the disease<br />

could be found in 21 countries in Africa and Asia,<br />

where 120 million residents were at risk of the<br />

infection. 2 Since then, cases have been reduced by<br />

more than 99.9 percent. At the end of 2015, there<br />

were only 22 cases in 20 villages in four countries:<br />

South Sudan, Ethiopia, Mali, and Chad. To date, the<br />

World Health Organization has certified 15 formerly<br />

endemic countries and 183 other countries and<br />

territories and areas as free of Guinea worm disease.<br />

Guinea worm is poised to be the second human<br />

disease and the first parasitic disease ever<br />

eradicated. The Carter Center and its partners assist<br />

the national Guinea worm eradication programs to<br />

halt transmission of the disease through:<br />

Education: Communities learn about the disease<br />

and how to prevent it. For example,<br />

people learn never to enter a source<br />

of drinking water if a Guinea worm is<br />

emerging, never to allow anyone else<br />

in the community with an emerging<br />

Guinea worm to do so, and to report<br />

anyone with Guinea worm.<br />

Surveillance: A comprehensive<br />

community-based surveillance<br />

network aims to detect and report<br />

cases of Guinea worm disease<br />

promptly (before or within 24 hours<br />

of worm emergence).<br />

Case containment: Individual<br />

cases are promptly managed<br />

(contained) to prevent infected<br />

people from contaminating sources of<br />

drinking water.<br />

Water treatment: Contaminated, stagnant<br />

sources of drinking water are treated with Abate ®<br />

(temephos), a safe chemical larvicide donated by<br />

BASF Corporation.<br />

Water filtration: Community members are taught to<br />

filter all unsafe drinking water to sieve out copepods<br />

and prevent infection. Cloth filters and pipe filters<br />

are donated by Vestergaard.<br />

As the lead agency over the last 30 years of the<br />

global Guinea worm eradication campaign, The<br />

Carter Center has raised $332.9 million in financial<br />

and in-kind contributions. Sources of support are<br />

illustrated in the chart below.<br />

An estimated $214 million is needed between 2015<br />

and 2020 to fully eradicate Guinea worm disease<br />

and to certify that the disease has been eradicated.<br />

As with any eradication campaign, the last cases<br />

will be the most expensive, but the ultimate reward<br />

is a world free of Guinea worm disease for future<br />

generations.<br />

Contributions and pledges for Guinea worm<br />

eradication by donor type, 1986–2014<br />

4%<br />

13%<br />

41%<br />

4%<br />

FPO<br />

38%<br />

Foundations<br />

Governments<br />

Organizations<br />

Corporations<br />

Individuals<br />

4

THE INTERVENTIONS<br />

The campaign will be successful when all<br />

countries are certified as free of Guinea worm<br />

disease. The following phases outline the work<br />

remaining to reach that goal. Ministries of health,<br />

national Guinea worm eradication programs and<br />

governments of affected countries are key partners<br />

in these efforts.<br />

Phase 1 Interruption of transmission in<br />

remaining endemic countries, led by endemic<br />

countries with support from The Carter<br />

Center: 2016<br />

• Ensure 100 percent coverage of active<br />

surveillance in remaining endemic areas,<br />

including regular case searches, investigation,<br />

documentation and response (within 24 hours) of<br />

rumored cases of Guinea worm disease.<br />

• Maintain surveillance and response capacity in<br />

areas of endemic countries where transmission<br />

has already been stopped.<br />

• Continue health education and mobilization,<br />

including distribution of cloth and pipe water<br />

filters, application of Abate larvicide to treat<br />

contaminated sources of drinking water, provision<br />

of safe drinking water, and promotion of cash<br />

rewards for reporting cases.<br />

• Conduct ongoing advocacy at national and<br />

international levels for continued support and<br />

funding to reach eradication.<br />

• Maintain cross-border surveillance and response<br />

capacity to prevent importation of cases and<br />

ensure that eradication status is maintained in all<br />

countries that have already been certified as free<br />

of Guinea worm disease. (WHO)<br />

Because many families in South Sudan, such as this child and her parents,<br />

move from place to place to care for their cattle, disease surveillance must<br />

cover a wide geographical area.<br />

Phase 2 Pre-certification, led by<br />

concerned countries with support<br />

from The Carter Center and WHO:<br />

2016–2019<br />

• Continue active surveillance in last<br />

group of endemic areas and immediate<br />

reporting and investigation of rumored<br />

cases. (The Carter Center)<br />

• Conduct ongoing advocacy at<br />

national and international levels for<br />

continued support and funding to<br />

reach eradication. (The Carter Center<br />

and WHO)<br />

• Facilitate external assessments to<br />

verify national claim that transmission has been<br />

interrupted. (WHO)<br />

• Implement a global reward for Guinea worm disease<br />

cases. (WHO)<br />

• Maintain cross-border surveillance and response<br />

capacity to prevent importation of cases and ensure<br />

that eradication status is maintained in all countries<br />

that have already been certified as free of Guinea<br />

worm disease. 3 (WHO)<br />

Phase 3 Certification, led by WHO: 2016–2020<br />

• Continue dissemination of information about<br />

rewards for Guinea worm disease cases.<br />

• Assist countries in preparing report for the<br />

International Commission for Certification of<br />

Dracunculiaisis Eradication (ICCDE).<br />

• Certify eight countries remaining, based on ICCDE<br />

assessment: Chad, Ethiopia, Mali, South Sudan,<br />

Kenya, Sudan, Angola, and Democratic Republic of<br />

the Congo.<br />

An Ethiopian<br />

community<br />

learns how to<br />

prevent Guinea<br />

worm disease.<br />

5

The extraction of<br />

a Guinea worm<br />

is a slow and<br />

painful process<br />

that can take up<br />

to two weeks<br />

or more for a<br />

single worm; if a<br />

worm is coaxed<br />

out forcefully, it<br />

can break and<br />

cause infection<br />

or permanent<br />

disability.<br />

6<br />

A health worker in Mali applies the<br />

safe larvicide Abate to a pond where<br />

people get their drinking water.<br />

SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC CASE<br />

FOR <strong>ERADICATION</strong><br />

The burden of Guinea worm disease on individuals,<br />

communities, and societies extends beyond<br />

physical suffering to significant economic and<br />

social consequences, hampering development and<br />

perpetuating a cycle of poverty and disease. 4 Due<br />

to its significant economic burden, Guinea worm<br />

disease is both a symptom of and contributor to<br />

poverty. The disease burden impacts adults and<br />

children alike, resulting in decreased agricultural<br />

and household productivity, as well as impinging<br />

on children’s school attendance.<br />

The economic burden on poor rural communities<br />

is particularly severe and aggravated by the<br />

seasonality of transmission, which coincides with<br />

peak agricultural activities. Agricultural laborers<br />

infected with Guinea worm disease are unable to<br />

harvest and farm crops (average duration of Guinea<br />

worm disability is eight weeks), affecting income<br />

and nutrition for families and the wider community. 5<br />

Additionally, children may be forced to take on<br />

work of their sick family members in the fields or<br />

in the home, causing absences at school. Children’s<br />

malnourishment or their own emerging Guinea<br />

worms that disable them from walking to school can<br />

further exacerbate the impact of the disease.<br />

The effort to eradicate Guinea worm disease is<br />

considered one of the most cost-effective health<br />

interventions available. Over 80 million cases have<br />

been averted since The Carter Center began working<br />

on the campaign in 1986, resulting in improved<br />

health status (including childcare and immunization<br />

coverage), agricultural productivity, and school<br />

attendance for millions of people in some of the most<br />

remote areas of the world at an estimated financial<br />

cost of $3.47 per case averted. Through communitybased<br />

health education, filtration of drinking water,<br />

application of Abate, and prompt detection of<br />

cases, Guinea worm disease can be affordably and<br />

effectively prevented.<br />

However, the costs per case of treatment and<br />

containment do increase toward the end of each<br />

national campaign and the end of the global<br />

campaign for the following reasons:<br />

Long incubation: The one-year-long incubation<br />

period makes it impossible to pre-identify infected<br />

carriers of the disease and ascertain who will develop<br />

infection. An extensive and intensive surveillance<br />

system must be maintained for at least one year<br />

beyond the report of the last indigenous case.<br />

Thus, the surveillance footprint of Guinea worm<br />

eradication programs must not only be maintained<br />

but must encompass all places where infected persons<br />

may be when they develop the disease.<br />

Prompt detection and containment: Interrupting<br />

transmission requires intensified operations during<br />

the last phase of each national eradication effort<br />

in order to detect all cases within 24 hours of<br />

worm emergence, to manage all patients promptly<br />

by case containment and to prevent transmission<br />

effectively, through treatment of contaminated<br />

sources of drinking water and ongoing community<br />

education about the need to consistently filter all<br />

drinking water.

Isolation and marginalization of affected<br />

communities: The dearth of public health<br />

infrastructure in Guinea worm endemic areas requires<br />

establishment and operation of case containment<br />

centers where patients with cases voluntarily<br />

admit themselves for health care and prevention<br />

of transmission. In addition, the last communities<br />

affected by Guinea worm disease are frequently the<br />

most marginalized by local society and distrustful<br />

of government programs and anyone of authority<br />

outside their communities. This often results in<br />

community reluctance to cooperate and likelihood to<br />

hide cases or withhold information about population<br />

movements or sources of drinking water, thus<br />

increasing the chances of missing cases. Community<br />

mobilization and trust are therefore essential.<br />

SUCCESS STORY: HUBEIDA IDDIRISU<br />

Above: In Ghana in 2007, volunteer Sulley Zakaria visits Hubeida Iddirisu at home to treat her three painful wounds where Guinea<br />

worms are emerging from her body. Right: Six years later Hubeida is a smiling teenager, and no one in her family, village, or country is<br />

at risk of the parasitic disease.<br />

In 2007, 11-year-old Hubeida Iddirisu faced<br />

long days of pain as three Guinea worms<br />

began to emerge from blisters on her body.<br />

Hubeida was the victim of a particularly severe<br />

Guinea worm disease outbreak in her town of<br />

Savelugu, Ghana.<br />

“I probably caught the worms when<br />

accepting a drink from a neighbor during my<br />

rounds of charcoal selling,” she said.<br />

Every day for two weeks, a volunteer<br />

came to Hubeida’s home to extract the<br />

worms. Often people suffer from more<br />

than one worm at a time, as Hubeida did,<br />

and the incapacitating wounds caused by<br />

the worms typically take up to two months<br />

to heal. While the worms were emerging,<br />

Hubeida was unable to attend school, handle<br />

her household tasks, or work at her afterschool<br />

job.<br />

During the outbreak, the Ghana Guinea<br />

Worm Eradication Program, assisted by The<br />

Carter Center and its partners, stepped up<br />

efforts to halt the disease in Savelugu by<br />

providing all households with cloth filters to<br />

strain out the Guinea worm larvae in drinking<br />

water. Community members with emerging<br />

worms were told not to enter sources of<br />

drinking water, such as the local dam, because<br />

doing so would allow the worms to release<br />

larvae into the water and continue the<br />

parasite’s life cycle. Stagnant ponds were also<br />

treated with a safe larvicide.<br />

One year later, Hubeida was free of Guinea<br />

worm disease. She was able to carry out her<br />

daily chores as well as her job selling charcoal<br />

to help support her family and pay for school<br />

fees.<br />

Today, Hubeida Iddirisu is a smiling young<br />

woman, and she has never had another<br />

Guinea worm. Ghana saw its last case of the<br />

disease in 2010 and was certified as free of<br />

Guinea worm disease in 2015.<br />

7

Guinea worm eradication campaign<br />

funding requirements, 2015–2020<br />

CALL TO ACTION<br />

Global eradication of Guinea worm disease requires<br />

unrelenting daily acts of courage by field workers in<br />

the four remaining endemic countries to break the<br />

transmission cycle. In spite of numerous challenges<br />

(including, but not limited to, insecurity and difficult<br />

access to endemic areas), the national Guinea worm<br />

eradication programs, assisted by The Carter Center<br />

and WHO, continue to deliver on their goals,<br />

steadily reducing cases, stopping transmission in<br />

endemic villages, and ensuring optimal surveillance<br />

and reporting. Continued perseverance and adequate<br />

funding will certainly ensure victory.<br />

Once transmission has been stopped globally, no<br />

further interventions or monitoring will be needed<br />

beyond the three-year-long precertification of<br />

eradication stage required by WHO. 6 The impact of<br />

success without a vaccine or curative drug will extend<br />

to validate the principle of disease eradication, the<br />

potential of community-based engagement and health<br />

education, and provide an example of a successful<br />

$156.97 million remaining<br />

$55.95 million confirmed<br />

$212.92 million total funding needed<br />

program for a neglected tropical disease. The legacy<br />

of the established health infrastructure and networks<br />

created to fight Guinea worm disease will include<br />

community-based surveillance and health education<br />

delivery systems ready to deliver other essential<br />

interventions. 7 Eradication will accrue economic<br />

returns forever by benefiting the health, agricultural<br />

productivity, and school attendance among some of<br />

the world’s poorest people.<br />

Join the global campaign. Your support is essential<br />

to maintaining momentum in the final push to<br />

eradicate Guinea worm disease.<br />

1 Cairncross S, Muller R, Zagaria N (2002). Dracunculiasis (Guinea worm disease)<br />

and the eradication initiative. Clin Microbiol Rev 15:223-246.<br />

2 Watts SJ. (1987) Dracunculiaisis in Africa in 1986: Its Geographic Extent,<br />

Incidence and At-Risk Population. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and<br />

Hygiene. 37(1): 119-125.<br />

3 See: http://apps.who.int/dracunculiasis/dradata/html/report_Countries_i1.html<br />

4 Levine R, What Works Working Group (2007): Case 11: reducing Guinea worm<br />

in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. In Case studies in global health: millions saved.<br />

Sudbury (Massachusetts): Jones & Bartlett Learning.<br />

5 Kim A, Tandon A, and Ruiz-Tiben E. (1997). Cost-Benefit Analysis of the<br />

Global Dracunculiasis Eradication Campaign (GDEC) Policy Research Working<br />

Paper, No 1835. The World Bank. Available on: http://www.cartercenter.org/<br />

documents/2101.pdf<br />

6 WHO, Dracunculiasis Fact Sheet. May 2015. Available on: http://www.who.int/<br />

mediacentre/factsheets/fs359/en/<br />

7 Callahan K, Bolton B, Hopkins DR, Ruiz-Tiben E, Withers PC, et al. (2013)<br />

Contributions of the Guinea Worm Eradication Campaign toward Achievement<br />

of the Millennium Development Goals. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 7 (5): e2160. Doi<br />

:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002160. Available on: http://www.cartercenter.org/<br />

resources/pdfs/news/health_publications/guinea_worm/plos-contributions-of-gweradication-toward-achievement-of-MDG.pdf<br />

For more details on how to support the<br />

Guinea worm eradication campaign,<br />

please contact:<br />

Nicole Kruse, nicole.kruse@cartercenter.org<br />

Kate Braband, kate.braband@cartercenter.org<br />

Chris Maddock, maddockc@who.int<br />

For the most up-to-date information, including<br />

a link to the current case count, go to<br />

www.cartercenter.org/guinea-worm.<br />

One Copenhill<br />

453 Freedom Parkway<br />

Atlanta, GA 30307<br />

www.cartercenter.org<br />

Avenue Appia 20<br />

1211 Geneva 27<br />

Switzerland<br />

www.who.int