YSM Issue 89.1

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

FOCUS<br />

evolution<br />

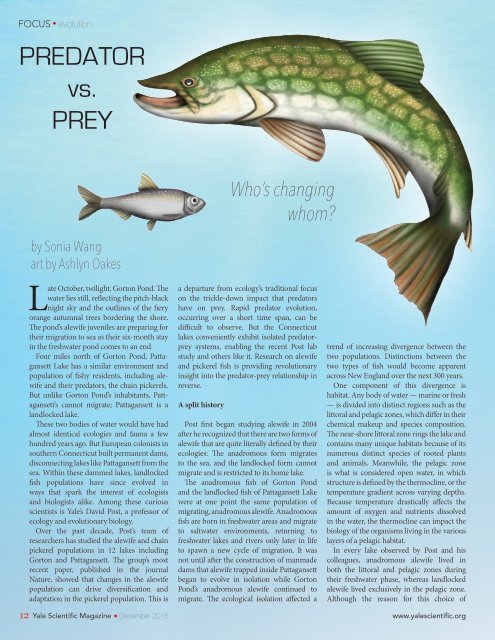

PREDATOR<br />

vs.<br />

PREY<br />

Who’s changing<br />

whom?<br />

by Sonia Wang<br />

art by Ashlyn Oakes<br />

Late October, twilight, Gorton Pond. The<br />

water lies still, reflecting the pitch-black<br />

night sky and the outlines of the fiery<br />

orange autumnal trees bordering the shore.<br />

The pond’s alewife juveniles are preparing for<br />

their migration to sea as their six-month stay<br />

in the freshwater pond comes to an end.<br />

Four miles north of Gorton Pond, Pattagansett<br />

Lake has a similar environment and<br />

population of fishy residents, including alewife<br />

and their predators, the chain pickerels.<br />

But unlike Gorton Pond’s inhabitants, Pattagansett’s<br />

cannot migrate; Pattagansett is a<br />

landlocked lake.<br />

These two bodies of water would have had<br />

almost identical ecologies and fauna a few<br />

hundred years ago. But European colonists in<br />

southern Connecticut built permanent dams,<br />

disconnecting lakes like Pattagansett from the<br />

sea. Within these dammed lakes, landlocked<br />

fish populations have since evolved in<br />

ways that spark the interest of ecologists<br />

and biologists alike. Among these curious<br />

scientists is Yale’s David Post, a professor of<br />

ecology and evolutionary biology.<br />

Over the past decade, Post’s team of<br />

researchers has studied the alewife and chain<br />

pickerel populations in 12 lakes including<br />

Gorton and Pattagansett. The group’s most<br />

recent paper, published in the journal<br />

Nature, showed that changes in the alewife<br />

population can drive diversification and<br />

adaptation in the pickerel population. This is<br />

a departure from ecology’s traditional focus<br />

on the trickle-down impact that predators<br />

have on prey. Rapid predator evolution,<br />

occurring over a short time span, can be<br />

difficult to observe. But the Connecticut<br />

lakes conveniently exhibit isolated predatorprey<br />

systems, enabling the recent Post lab<br />

study and others like it. Research on alewife<br />

and pickerel fish is providing revolutionary<br />

insight into the predator-prey relationship in<br />

reverse.<br />

A split history<br />

Post first began studying alewife in 2004<br />

after he recognized that there are two forms of<br />

alewife that are quite literally defined by their<br />

ecologies: The anadromous form migrates<br />

to the sea, and the landlocked form cannot<br />

migrate and is restricted to its home lake.<br />

The anadromous fish of Gorton Pond<br />

and the landlocked fish of Pattagansett Lake<br />

were at one point the same population of<br />

migrating, anadromous alewife. Anadromous<br />

fish are born in freshwater areas and migrate<br />

to saltwater environments, returning to<br />

freshwater lakes and rivers only later in life<br />

to spawn a new cycle of migration. It was<br />

not until after the construction of manmade<br />

dams that alewife trapped inside Pattagansett<br />

began to evolve in isolation while Gorton<br />

Pond’s anadromous alewife continued to<br />

migrate. The ecological isolation affected a<br />

trend of increasing divergence between the<br />

two populations. Distinctions between the<br />

two types of fish would become apparent<br />

across New England over the next 300 years.<br />

One component of this divergence is<br />

habitat. Any body of water — marine or fresh<br />

— is divided into distinct regions such as the<br />

littoral and pelagic zones, which differ in their<br />

chemical makeup and species composition.<br />

The near-shore littoral zone rings the lake and<br />

contains many unique habitats because of its<br />

numerous distinct species of rooted plants<br />

and animals. Meanwhile, the pelagic zone<br />

is what is considered open water, in which<br />

structure is defined by the thermocline, or the<br />

temperature gradient across varying depths.<br />

Because temperature drastically affects the<br />

amount of oxygen and nutrients dissolved<br />

in the water, the thermocline can impact the<br />

biology of the organisms living in the various<br />

layers of a pelagic habitat.<br />

In every lake observed by Post and his<br />

colleagues, anadromous alewife lived in<br />

both the littoral and pelagic zones during<br />

their freshwater phase, whereas landlocked<br />

alewife lived exclusively in the pelagic zone.<br />

Although the reason for this choice of<br />

12 Yale Scientific Magazine December 2015 www.yalescientific.org