After Return

After%20Return_RSN_April%202016

After%20Return_RSN_April%202016

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

6. Networks and support<br />

Case study 1: Erfanullah<br />

Erfanullah and his sister fled Afghanistan when their uncle killed their father and brother.<br />

While they were in the UK, they lost contact with their mother. On his return to Afghanistan,<br />

Erfanullah avoided further problems with his uncle by living a safe distance from him.<br />

His sister had been granted permission to stay in the UK and Erfanullah described his<br />

devastation at being separated from her. “I was crying that I don’t want to go. I want my<br />

sister. No one listened,” he explained. “They restrained my wrists and beat me. It was too<br />

hard. I wanted to stay with my sister” (R12, IM1).<br />

<strong>After</strong> his removal, Erfanullah’s sister continued to support him by sending him money and<br />

talking to solicitors in the UK to find out if she could bring him back. Over the coming months,<br />

being reunited with his sister remained his top priority.<br />

At least four young people who were able to find<br />

their families spoke of being confronted with hostility<br />

and disappointment when they returned to their<br />

family. Often living in poverty and sometimes still<br />

indebted from financing the initial migration of the<br />

young returnee, families’ resources were under strain.<br />

A lack of understanding of the circumstances under<br />

which young people may be forcibly removed from<br />

the UK further exacerbated relations, with one young<br />

returnee describing his uncle’s reaction to his return<br />

as “heartbreaking”, because, “he thinks the same<br />

as most Afghans think” and “told me told me I must<br />

have committed a crime due to which I have been<br />

deported back to Afghanistan. I have been trying<br />

to explain him about the condition and policies UK<br />

have, but it doesn’t work” (R24, IAR).<br />

These tensions characterised many family<br />

relationships after return, and have increased young<br />

returnees’ sense of urgency in finding work (see<br />

Chapter 9 for more on employment) to enable them<br />

to contribute as expected to the family unit, or live<br />

independently when they can no longer stay with<br />

family.<br />

Friends<br />

Like family, friends too were a primary source of<br />

support for many of the young people on return<br />

to Afghanistan, yet, for just over half of the young<br />

returnees monitored, making and maintaining<br />

friendships after return was challenging. When asked<br />

about friends, the majority of young people who had<br />

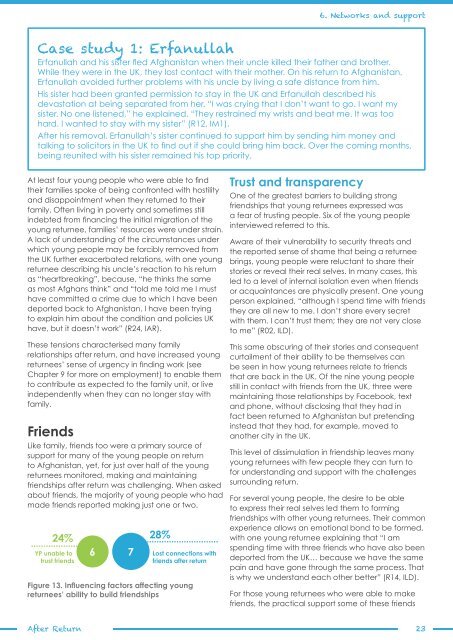

made friends reported making just one or two.<br />

24%<br />

YP unable to<br />

trust friends<br />

6 7<br />

28%<br />

Lost connections with<br />

friends after return<br />

Figure 13. Influencing factors affecting young<br />

returnees’ ability to build friendships<br />

Trust and transparency<br />

One of the greatest barriers to building strong<br />

friendships that young returnees expressed was<br />

a fear of trusting people. Six of the young people<br />

interviewed referred to this.<br />

Aware of their vulnerability to security threats and<br />

the reported sense of shame that being a returnee<br />

brings, young people were reluctant to share their<br />

stories or reveal their real selves. In many cases, this<br />

led to a level of internal isolation even when friends<br />

or acquaintances are physically present. One young<br />

person explained, “although I spend time with friends<br />

they are all new to me. I don’t share every secret<br />

with them. I can’t trust them; they are not very close<br />

to me” (R02, ILD).<br />

This same obscuring of their stories and consequent<br />

curtailment of their ability to be themselves can<br />

be seen in how young returnees relate to friends<br />

that are back in the UK. Of the nine young people<br />

still in contact with friends from the UK, three were<br />

maintaining those relationships by Facebook, text<br />

and phone, without disclosing that they had in<br />

fact been returned to Afghanistan but pretending<br />

instead that they had, for example, moved to<br />

another city in the UK.<br />

This level of dissimulation in friendship leaves many<br />

young returnees with few people they can turn to<br />

for understanding and support with the challenges<br />

surrounding return.<br />

For several young people, the desire to be able<br />

to express their real selves led them to forming<br />

friendships with other young returnees. Their common<br />

experience allows an emotional bond to be formed,<br />

with one young returnee explaining that “I am<br />

spending time with three friends who have also been<br />

deported from the UK… because we have the same<br />

pain and have gone through the same process. That<br />

is why we understand each other better” (R14, ILD).<br />

For those young returnees who were able to make<br />

friends, the practical support some of these friends<br />

<strong>After</strong> <strong>Return</strong> 23