After Return

After%20Return_RSN_April%202016

After%20Return_RSN_April%202016

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

8. Education and training<br />

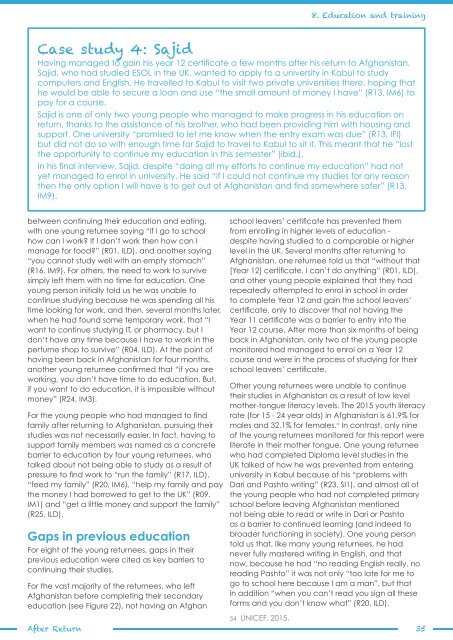

Case study 4: Sajid<br />

Having managed to gain his year 12 certificate a few months after his return to Afghanistan,<br />

Sajid, who had studied ESOL in the UK, wanted to apply to a university in Kabul to study<br />

computers and English. He travelled to Kabul to visit two private universities there, hoping that<br />

he would be able to secure a loan and use “the small amount of money I have” (R13, IM6) to<br />

pay for a course.<br />

Sajid is one of only two young people who managed to make progress in his education on<br />

return, thanks to the assistance of his brother, who had been providing him with housing and<br />

support. One university “promised to let me know when the entry exam was due” (R13, IFI)<br />

but did not do so with enough time for Sajid to travel to Kabul to sit it. This meant that he “lost<br />

the opportunity to continue my education in this semester” (ibid.).<br />

In his final interview, Sajid, despite “doing all my efforts to continue my education” had not<br />

yet managed to enrol in university. He said “if I could not continue my studies for any reason<br />

then the only option I will have is to get out of Afghanistan and find somewhere safer” (R13,<br />

IM9).<br />

between continuing their education and eating,<br />

with one young returnee saying “if I go to school<br />

how can I work? If I don’t work then how can I<br />

manage for food?” (R01, ILD), and another saying<br />

“you cannot study well with an empty stomach”<br />

(R16, IM9). For others, the need to work to survive<br />

simply left them with no time for education. One<br />

young person initially told us he was unable to<br />

continue studying because he was spending all his<br />

time looking for work, and then, several months later,<br />

when he had found some temporary work, that “I<br />

want to continue studying IT, or pharmacy, but I<br />

don’t have any time because I have to work in the<br />

perfume shop to survive” (R04, ILD). At the point of<br />

having been back in Afghanistan for four months,<br />

another young returnee confirmed that “if you are<br />

working, you don’t have time to do education. But,<br />

if you want to do education, it is impossible without<br />

money” (R24, IM3).<br />

For the young people who had managed to find<br />

family after returning to Afghanistan, pursuing their<br />

studies was not necessarily easier. In fact, having to<br />

support family members was named as a concrete<br />

barrier to education by four young returnees, who<br />

talked about not being able to study as a result of<br />

pressure to find work to “run the family” (R17, ILD),<br />

“feed my family” (R20, IM6), “help my family and pay<br />

the money I had borrowed to get to the UK” (R09,<br />

IM1) and “get a little money and support the family”<br />

(R25, ILD).<br />

Gaps in previous education<br />

For eight of the young returnees, gaps in their<br />

previous education were cited as key barriers to<br />

continuing their studies.<br />

For the vast majority of the returnees, who left<br />

Afghanistan before completing their secondary<br />

education (see Figure 22), not having an Afghan<br />

school leavers’ certificate has prevented them<br />

from enrolling in higher levels of education -<br />

despite having studied to a comparable or higher<br />

level in the UK. Several months after returning to<br />

Afghanistan, one returnee told us that “without that<br />

[Year 12] certificate, I can’t do anything” (R01, ILD),<br />

and other young people explained that they had<br />

repeatedly attempted to enrol in school in order<br />

to complete Year 12 and gain the school leavers’<br />

certificate, only to discover that not having the<br />

Year 11 certificate was a barrier to entry into the<br />

Year 12 course. <strong>After</strong> more than six months of being<br />

back in Afghanistan, only two of the young people<br />

monitored had managed to enrol on a Year 12<br />

course and were in the process of studying for their<br />

school leavers’ certificate.<br />

Other young returnees were unable to continue<br />

their studies in Afghanistan as a result of low level<br />

mother-tongue literacy levels. The 2015 youth literacy<br />

rate (for 15 - 24 year olds) in Afghanistan is 61.9% for<br />

males and 32.1% for females. 54 In contrast, only nine<br />

of the young returnees monitored for this report were<br />

literate in their mother tongue. One young returnee<br />

who had completed Diploma level studies in the<br />

UK talked of how he was prevented from entering<br />

university in Kabul because of his “problems with<br />

Dari and Pashto writing” (R23, SI1), and almost all of<br />

the young people who had not completed primary<br />

school before leaving Afghanistan mentioned<br />

not being able to read or write in Dari or Pashto<br />

as a barrier to continued learning (and indeed to<br />

broader functioning in society). One young person<br />

told us that, like many young returnees, he had<br />

never fully mastered writing in English, and that<br />

now, because he had “no reading English really, no<br />

reading Pashto” it was not only “too late for me to<br />

go to school here because I am a man”, but that<br />

in addition “when you can’t read you sign all these<br />

forms and you don’t know what” (R20, ILD).<br />

54 UNICEF. 2015.<br />

<strong>After</strong> <strong>Return</strong> 35