Entire document - Australia Council for the Arts

Entire document - Australia Council for the Arts

Entire document - Australia Council for the Arts

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

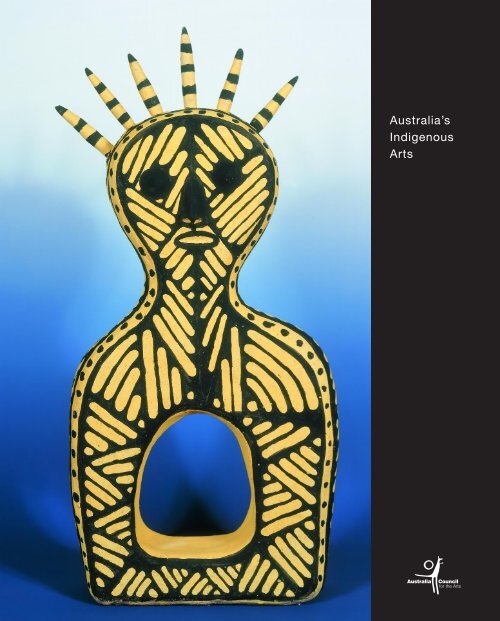

<strong>Australia</strong>’s<br />

Indigenous<br />

<strong>Arts</strong>

2<br />

Dear Reader<br />

This publication introduces you to just some of <strong>the</strong> many significant Indigenous<br />

artists working in <strong>Australia</strong> today. The term 'Indigenous', like 'Aboriginal', is not<br />

at all adequate to describe <strong>the</strong> regional, linguistic and cultural diversity of<br />

Aboriginal people across a huge continent. However, we hope this publication<br />

encourages you to engage with a complex culture.<br />

This publication includes details of <strong>Australia</strong>n works to be presented at <strong>the</strong><br />

Festival of Pacific <strong>Arts</strong> and <strong>the</strong> Biennale of Contemporary Art in Noumea,<br />

New Caledonia, 23 October - 3 November 2000. Participation in <strong>the</strong>se<br />

events is indicated at <strong>the</strong> end of each artist’s entry.<br />

The art <strong>for</strong>m sections (essays, references and individual artist entries) are<br />

followed by an extensive database on pages 52 - 53.<br />

The Editors<br />

A note about language and identity<br />

The Aboriginal peoples of <strong>Australia</strong> primarily identify <strong>the</strong>mselves by <strong>the</strong> language<br />

groups to which <strong>the</strong>y belong, calling <strong>the</strong>m Nations. Be<strong>for</strong>e <strong>the</strong> white colonisation<br />

of <strong>Australia</strong> <strong>the</strong>re were hundreds of language groups. There are fewer now but<br />

<strong>the</strong> number is still considerable. You will see that many of <strong>the</strong> artists appearing<br />

in this publication are identified by Nation—<strong>the</strong> language groups include names<br />

such as Wiradjuri, Larrakia and Arrernte. Ano<strong>the</strong>r set of terms is broadly regional<br />

and approximates roughly, but not always, to <strong>the</strong> states of <strong>Australia</strong>—Nyoongar<br />

(Western <strong>Australia</strong>), Nunga (South <strong>Australia</strong>), Murri (Queensland), Koori (New<br />

South Wales and Victoria), and Pallawah (Tasmania). It should be noted that<br />

spelling of <strong>the</strong> names <strong>for</strong> Nations and regional groups varies eg Noongar or<br />

Nyoongar in Western <strong>Australia</strong>.<br />

Editors Virginia Baxter, Keith Gallasch<br />

Design i2i design, Sydney<br />

Cover photographs: John Patrick Kelantumama (aka Yell). Front: Purukuparli<br />

(Fa<strong>the</strong>r), 630 mm x 320 mm x 120 mm, (yellow & black). Back cover: Jinani<br />

(son) 620 mm x 280 mm x 100 mm (turquoise and black). Underglaze pigment<br />

on ear<strong>the</strong>nware. Collection: Di Yerbury. Photographer: Lucio Nigro<br />

Produced by RealTime <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Australia</strong> <strong>Council</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>Australia</strong>n Government's arts funding and advisory body<br />

<strong>Australia</strong> <strong>Council</strong><br />

PO Box 788<br />

Strawberry Hills NSW 2012<br />

61 2 9215 9000 fax 61 2 9215 9111<br />

mail@ozco.gov.au<br />

www.ozco.gov.au<br />

RealTime<br />

PO Box A2246<br />

Sydney South NSW 1235<br />

opencity@rtimearts.com<br />

www.rtimearts.com/~opencity/<br />

May 2000 ISBN 0 642 47230 0

new media<br />

music<br />

visual arts<br />

film<br />

<strong>the</strong>atre<br />

dance<br />

indigenous<br />

literature<br />

<strong>Australia</strong>'s Indigenous arts are <strong>the</strong> focus of a great surge of international interest<br />

in <strong>Australia</strong>'s arts and culture. It is no exaggeration to say that our Indigenous<br />

arts are <strong>Australia</strong>'s most significant cultural asset. Both ancient and modern,<br />

<strong>the</strong>y are a profound and powerful <strong>for</strong>ce in <strong>the</strong> <strong>Australia</strong>n cultural landscape.<br />

Contemporary <strong>Australia</strong> in its growing maturity recognises that beyond <strong>the</strong><br />

cliched images of Indigenous <strong>Australia</strong> exists a complex and diverse culture<br />

stretching back over 40,000 years and which now speaks profoundly to us in<br />

<strong>the</strong> present as we seek reconciliation.<br />

Arguably <strong>the</strong> world's oldest culture coupled with innovative endeavour in every<br />

art <strong>for</strong>m has produced an extraordinarily rich and challenging blend of arts. The<br />

<strong>Australia</strong> <strong>Council</strong>, through its Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander <strong>Arts</strong> Fund, is<br />

proud to have played a sustained role in this development.<br />

The <strong>Australia</strong>n program <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> 8th Festival of <strong>the</strong> Pacific <strong>Arts</strong> represents <strong>the</strong><br />

great diversity and uniqueness of <strong>Australia</strong>'s Indigenous arts from remote<br />

<strong>Australia</strong> to our coastal cities. To reflect <strong>the</strong> significance of <strong>the</strong> Festival, <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Australia</strong> <strong>Council</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> first time appointed an Artistic Director <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Australia</strong>n program. Rea is a celebrated artist grounded in <strong>the</strong> arts and culture<br />

of her people and on behalf of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Australia</strong> <strong>Council</strong> I congratulate and thank<br />

Rea <strong>for</strong> her vision in creating such a brilliant, exciting and illuminating program.<br />

Much of <strong>the</strong> material in this publication draws on Rea's program to provide both<br />

a snapshot and a guide to <strong>Australia</strong>'s Indigenous arts which I am sure will prove<br />

a valuable resource and provide insights <strong>for</strong> both <strong>Australia</strong>n and international<br />

audiences alike.<br />

Jennifer Bott<br />

Chief Executive Officer<br />

<strong>Australia</strong> <strong>Council</strong><br />

Art has always been integral to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people's<br />

lives—as an expression of our spiritual connection with <strong>the</strong> land and sea, and as<br />

a ceremonial and educational tool of lore and <strong>the</strong> Dreaming.<br />

Diversity abounds throughout our arts and cultures with every community realising<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir own distinctive interpretations. <strong>Arts</strong> often powerfully reflect our political, legal,<br />

historical and cultural concerns with many artists bringing issues of dispossession<br />

to non-indigenous audiences—from land rights to Aboriginal Deaths in Custody to<br />

<strong>the</strong> Stolen Generations (children who were <strong>for</strong>cibly removed from <strong>the</strong>ir families). Art<br />

has <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e played a vital role in our survival since colonisation, allowing us to<br />

affirm and assert our individual and collective identities.<br />

An excellent insight into <strong>the</strong> significance of art to Indigenous <strong>Australia</strong>ns, this<br />

publication also reveals <strong>the</strong> importance of our art—through its popularity and<br />

international status—to all <strong>Australia</strong>ns.<br />

Richard Walley<br />

Chair, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander <strong>Arts</strong> Fund<br />

<strong>Australia</strong> <strong>Council</strong><br />

3

4<br />

Indigenous art + content + context = many meanings*<br />

A few weeks ago I was in a taxi on<br />

my way to a festival meeting when<br />

<strong>the</strong> driver, a reasonably young,<br />

white woman began to launch into<br />

a rave about 'aboriginal art'.<br />

Un<strong>for</strong>tunately, I have been<br />

subjected to a number of <strong>the</strong>se<br />

'taxi monologues' and even more<br />

un<strong>for</strong>tunately, <strong>the</strong>y are essentially,<br />

always <strong>the</strong> same—an excuse <strong>for</strong><br />

white <strong>Australia</strong>ns to vent <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

ignorance, racism and total lack of<br />

understanding of Aboriginal art +<br />

culture. The taxi driver was<br />

adamant, "All <strong>Australia</strong>ns should be<br />

allowed to paint <strong>the</strong> <strong>Australia</strong>n<br />

landscape. And, we should be<br />

allowed to use dots and snakes<br />

and fish (her list was endless). And<br />

you know what—we are all<br />

<strong>Australia</strong>ns and we all live here and<br />

you lot—you aborigines (I hate that<br />

word) don't own this stuff".<br />

I immediately felt a deep sense of<br />

despair at what I was hearing.<br />

Obviously, moving into <strong>the</strong> new<br />

century had somehow tricked me<br />

into believing—maybe even<br />

hoping—that <strong>the</strong>re had been a shift<br />

in how white <strong>Australia</strong>ns perceive<br />

and <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e, understand and<br />

respect Indigenous art + culture.<br />

But here I was being let know loud<br />

and clear that <strong>Australia</strong> is still<br />

dominated by past ideologies and<br />

outmoded beliefs. One of <strong>the</strong><br />

strongest of <strong>the</strong>se beliefs has<br />

always been that we (<strong>the</strong><br />

Indigenous people) must be kept in<br />

our place, which has always been<br />

on <strong>the</strong> fringes of <strong>the</strong> white society—<br />

<strong>the</strong>y don't like it when we demand<br />

our right to be visible in our own<br />

land and to determine how we will<br />

be (re)presented.<br />

There have been many attempts by<br />

<strong>the</strong> 'white' art world to homogenise<br />

Aboriginal art—after all, a fish is a<br />

fish is a fish and a snake is a snake<br />

is a … isn't it? Wrong. All<br />

Indigenous artists are connected to<br />

specific lands which contain sacred<br />

sites and <strong>the</strong>re<strong>for</strong>e, distinctive 'art'<br />

styles and specific cultural<br />

meanings are accorded to <strong>the</strong><br />

symbols and icons that each<br />

community images within <strong>the</strong>ir art.<br />

And while two communities might<br />

share a symbol or even two, <strong>the</strong><br />

exact meaning <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> symbol(s)<br />

is clearly defined and particular to<br />

each community's land, stories,<br />

traditions and creation myths.<br />

The same white art world has also<br />

arbitrarily defined and divided<br />

Indigenous art by divorcing it from<br />

its essence—that is, <strong>the</strong> artists who<br />

actually create <strong>the</strong> work. In this<br />

binary, Indigenous art is positioned<br />

as ei<strong>the</strong>r 'traditional' which means<br />

created by Indigenous artists who<br />

come from regional and remote<br />

areas of <strong>Australia</strong> and who are<br />

viewed as au<strong>the</strong>ntic/real (that is<br />

<strong>the</strong>y look stereotypically ‘blak’) +<br />

hence, <strong>the</strong>ir work has, in <strong>the</strong> past<br />

been seen as being of value<br />

culturally + economically to <strong>the</strong><br />

same white art world. Un<strong>for</strong>tunately,<br />

<strong>the</strong> 'contemporary' work has been<br />

totally de-valued in this equation<br />

even though it is also created by<br />

Indigenous artists who tend to<br />

come from <strong>the</strong> urban centres of<br />

<strong>Australia</strong> + <strong>the</strong>ir work is more often<br />

than not perceived as<br />

inau<strong>the</strong>ntic/not 'blak'<br />

enough/culturally vague +<br />

unspecific + far too political.**<br />

I firmly believe, firstly that all<br />

Indigenous art is political no matter<br />

what region it comes from and as<br />

Aboriginal leader Galarrwuy<br />

Yunupingu states, "We are painting<br />

as we have always done, to<br />

demonstrate our continuing link<br />

with our country and <strong>the</strong> rights and<br />

<strong>the</strong> responsibilities that we have to<br />

it. We paint to show <strong>the</strong> rest of <strong>the</strong><br />

world that we own this country and<br />

<strong>the</strong> land owns us. Our painting is a<br />

political act." Secondly, all<br />

Indigenous art is contemporary, as<br />

writer and curator Djon Mundine<br />

once said, "if it is being created by<br />

Indigenous artists NOW."<br />

Indigenous <strong>Australia</strong>ns (including<br />

artists) have had to fight long + hard<br />

<strong>for</strong> visibility + recognition. For us it<br />

has been just one of many struggles<br />

we have been <strong>for</strong>ced to engage in<br />

<strong>for</strong> our continued survival culturally,<br />

politically, socially + economically<br />

since <strong>the</strong> British landed on our<br />

shores in 1788 and declared <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

doctrine of 'terra nullius'. Our fight<br />

continues on a daily basis but today<br />

it also involves our 'healing' as well<br />

as our ongoing struggle <strong>for</strong> land<br />

rights + human rights.<br />

I would like to thank all <strong>the</strong> artists<br />

who have generously given<br />

<strong>the</strong>mselves via <strong>the</strong>ir art because,<br />

like <strong>the</strong>m, I know that our art is<br />

essential to our living cultures +<br />

survival as it enables us to re-locate<br />

+ re-enter our histories. It gives us<br />

<strong>the</strong> visibility to reclaim our identities.<br />

I truly believe it is my generation<br />

who will take charge of <strong>the</strong><br />

processes needed to revive our<br />

cultures, building on <strong>the</strong> rich<br />

foundations laid by our ancestors.<br />

I only hope we can continue to<br />

move <strong>for</strong>ward with <strong>the</strong> same sense<br />

of pride, principles, and respect<br />

towards each o<strong>the</strong>r which our<br />

ancestors displayed.<br />

Rea<br />

Artistic Director,<br />

<strong>Australia</strong>n Indigenous Program<br />

8th Festival of Pacific <strong>Arts</strong><br />

*This is an edited version of Rea's<br />

essay <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> catalogue, Biennale of<br />

Contemporary <strong>Arts</strong>, Noumea.<br />

**The term 'Blak' was developed by<br />

artist Destiny Deacon as a part of a<br />

symbolic but potent strategy of<br />

reclaiming colonialist language to<br />

create means of self-definition<br />

and expression. H Perkins,<br />

C Williamson, Blakness, Blak City<br />

Culture!, 1994.

<strong>the</strong>atre<br />

Indigenous <strong>the</strong>atre: The future in black and white<br />

There's nothing I would ra<strong>the</strong>r be<br />

Than to be an Aborigine<br />

and watch you take my precious land away.<br />

For nothing gives me greater joy<br />

than to watch you fill each girl and boy<br />

with superficial existential shit.<br />

Now you may think I'm cheeky<br />

But I'd be satisfied<br />

to rebuild your convict ships<br />

and sail <strong>the</strong>m on <strong>the</strong> tide.<br />

I love <strong>the</strong> way you give me God<br />

and of course <strong>the</strong> mining board,<br />

<strong>for</strong> this of course I thank <strong>the</strong> Lord each day.<br />

I'm glad you say that land rights wrong.<br />

Then you should go where you belong<br />

and leave me to just keep on keeping on.<br />

This is one of <strong>the</strong> songs from Bran<br />

Nue Dae, a musical which emerged<br />

in 1989 from one of <strong>the</strong> most<br />

remote parts of <strong>Australia</strong>: <strong>the</strong> port<br />

of Broome on <strong>the</strong> North-West<br />

coast. It has since been widely<br />

per<strong>for</strong>med and toured, its music<br />

recorded and a television<br />

<strong>document</strong>ary broadcast nationally.<br />

The song itself has become an<br />

an<strong>the</strong>m <strong>for</strong> Aboriginal people, a rare<br />

unifying <strong>for</strong>ce <strong>for</strong> empowerment. Its<br />

quality has appealed equally to<br />

white <strong>Australia</strong>ns: its tune is<br />

infectious and celebratory, creating<br />

a tension with <strong>the</strong> words which<br />

expresses both Aboriginal defiance<br />

of <strong>the</strong>ir situation as a colonised<br />

people, and an ironic selfaccusation<br />

<strong>for</strong> accepting it. The<br />

author is Jimmy Chi, a musician of<br />

mixed blood, including Aboriginal,<br />

Chinese and Japanese; and <strong>the</strong><br />

stage show evolved from <strong>the</strong> songs<br />

created by his band, Kuckles, one<br />

of dozens of bands which play in<br />

<strong>the</strong> pubs in Broome.<br />

Bran Nue Dae in 1989 was a<br />

turning point in <strong>the</strong> short history of<br />

Aboriginal writing <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>atre.<br />

Twenty years of evolution in writers,<br />

political activists, actors, dancers,<br />

singers and song-writers preceded<br />

it. It was, surprisingly, only in <strong>the</strong><br />

1960s that Aboriginal writers began<br />

to be published in numbers<br />

recognisable as a body of work.<br />

This occurred as part of a ga<strong>the</strong>ring<br />

<strong>for</strong>ce of activism by a politically<br />

aware post-war generation of<br />

Aborigines and of young white<br />

people, particularly university<br />

students. In 1961 Aborigines had<br />

finally been given <strong>the</strong> vote. In 1965<br />

Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Territory Aboriginal<br />

pastoral workers were awarded<br />

equal pay with whites; in 1966 <strong>the</strong><br />

first major land-rights strike took<br />

place; and in 1967 a national<br />

referendum overwhelmingly voted in<br />

favour of transferring judicial<br />

responsibility <strong>for</strong> Aboriginal welfare<br />

from <strong>the</strong> states to <strong>the</strong> Commonwealth<br />

government. Isolated protests<br />

over local issues, mainly to do with<br />

living conditions on reserves,<br />

became by degrees an organised<br />

civil rights movement which gained<br />

confidence from <strong>the</strong> parallel<br />

movement in <strong>the</strong> United States.<br />

Encouraged by public statements,<br />

individual voices began to be heard.<br />

Poetry and song came first, drama<br />

followed. The civil rights movement<br />

coincided with—or ra<strong>the</strong>r shared<br />

<strong>the</strong> same roots as—<strong>the</strong> anti-British,<br />

anti-American, anti-Vietnam War<br />

nationalism that changed <strong>the</strong><br />

politics of <strong>Australia</strong> in <strong>the</strong> late 60s<br />

and brought into existence, as a<br />

by-product, <strong>the</strong> <strong>Australia</strong>n <strong>Council</strong><br />

<strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>Arts</strong>, now <strong>the</strong> <strong>Australia</strong><br />

<strong>Council</strong>. Its Aboriginal and Torres<br />

Strait Islander <strong>Arts</strong> Board (now<br />

Fund) has been an important<br />

source of funds <strong>for</strong> Indigenous arts<br />

groups and <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> development of<br />

individual talent.<br />

Now, after thirty years of growing<br />

confidence, Aboriginal and Torres<br />

Strait Islander artists have reached<br />

<strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>efront of our arts. Thirty years<br />

ago few urban white <strong>Australia</strong>ns had<br />

ever seen a traditional Aboriginal<br />

painting—had rarely even seen an<br />

Aboriginal. Few whites knew<br />

anything of <strong>the</strong> Aboriginal way of life,<br />

with its complex social order and<br />

spirituality, its practical jokes, its<br />

ingenious survival skills and its talent<br />

<strong>for</strong> parody. We were not even aware<br />

of our own ignorance—until it was<br />

exposed by <strong>the</strong> revelations on stage<br />

and on television. Today in <strong>Australia</strong>n<br />

<strong>the</strong>atre, at least in my view, <strong>the</strong> most<br />

important new work is Aboriginal—<br />

and will, in due course, be <strong>the</strong> most<br />

widely seen in o<strong>the</strong>r countries.<br />

The earliest play from this<br />

contemporary movement was Kevin<br />

Gilbert's The Cherry Pickers, <strong>the</strong><br />

first half of which was first seen at a<br />

private per<strong>for</strong>mance in Sydney in<br />

1971. The dialogue was goodhearted<br />

and good-humoured and<br />

<strong>the</strong> subject matter small community<br />

affairs. I was suddenly overawed at<br />

being allowed into <strong>the</strong> domestic life<br />

of a people whose privacy had, <strong>for</strong><br />

so long and <strong>for</strong> such good reason,<br />

been guarded from white eyes. The<br />

play was later per<strong>for</strong>med in<br />

Melbourne by <strong>the</strong> Nindethana<br />

Theatre, <strong>the</strong> first of <strong>the</strong> black<br />

companies. Kevin Gilbert had at<br />

that time just been released from<br />

gaol. He became a leading figure in<br />

<strong>the</strong> civil rights movement,<br />

uncompromising in his ethics and a<br />

poet of distinction. He died in 1992,<br />

mourned by both blacks and<br />

whites. Wesley Enoch is directing<br />

The Cherry Pickers <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> Sydney<br />

Theatre Company in 2000.<br />

O<strong>the</strong>r works followed. The political<br />

revue Basically Black was<br />

per<strong>for</strong>med in 1972 at <strong>the</strong> Nimrod<br />

Street Theatre in Sydney, with a<br />

cast including Gary Foley, Zac<br />

Martin and <strong>the</strong> late Bob Maza,<br />

soon to be well-known figures. The<br />

revue was a response to a High<br />

Court ruling against a traditional<br />

claim to land ownership, and <strong>the</strong><br />

participants were instigators of <strong>the</strong><br />

Aboriginal Embassy in Canberra—a<br />

tent bearing <strong>the</strong> Aboriginal banner<br />

which had been pitched, as a<br />

demand <strong>for</strong> recognition, on <strong>the</strong><br />

lawn outside Parliament House.<br />

Out of that group grew <strong>the</strong> Black<br />

Theatre in Redfern, Sydney. Among<br />

<strong>the</strong> plays I saw in that crumbling<br />

warehouse was Here Comes <strong>the</strong><br />

Nigger (1976), a contemporary<br />

tragedy by Gerry Bostock. Ano<strong>the</strong>r<br />

was Robert Merritt's The Cake<br />

Man, <strong>the</strong> first Aboriginal play to<br />

enter <strong>the</strong> repertoire of <strong>the</strong> white<br />

<strong>the</strong>atre and in 1982 received with<br />

acclaim at an international festival<br />

in Denver, Colorado. Through <strong>the</strong><br />

simple tale of a child's faith it gave<br />

white audiences a shock of insight<br />

into <strong>the</strong> despair of life on a country<br />

town reserve. Its progress owed<br />

much to <strong>the</strong> pioneering actors<br />

Justine Saunders and Brian Syron;<br />

and <strong>the</strong>y became major <strong>for</strong>ces in<br />

<strong>the</strong> black <strong>the</strong>atre movement.<br />

Syron had escaped from an abused<br />

childhood to New York in <strong>the</strong> late<br />

50s, where he became a star pupil<br />

at <strong>the</strong> Stella Adler studio, set <strong>for</strong> a<br />

promising career in Hollywood. But<br />

in 1968 he was drawn back to<br />

<strong>Australia</strong>, called home, he said, by<br />

<strong>the</strong> apparition of a tribal elder. He<br />

was <strong>the</strong> first Aboriginal to have had<br />

that kind of extensive <strong>the</strong>atre<br />

training and his school in Sydney<br />

became a centre <strong>for</strong> actors, both<br />

black and white, who sought a<br />

more daring and Indigenous style of<br />

expression. He died in 1993, aged<br />

only 53.<br />

In 1979, <strong>the</strong> nudging of a few<br />

consciences over <strong>the</strong> Western<br />

<strong>Australia</strong>n sesquicentenary<br />

5

6<br />

provided circumstances in which<br />

our major black playwright, Jack<br />

Davis (1917-2000), could make his<br />

mark. Davis found himself writing<br />

Kullark, <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>atre-in-education<br />

troupe of <strong>the</strong> National Theatre in<br />

Perth. Through a number of<br />

metamorphoses a team of actors<br />

and dancers emerged in Perth to<br />

give a wholly new status to<br />

per<strong>for</strong>mance by Aboriginal artists.<br />

Of national reputation are <strong>the</strong> actor<br />

Ernie Dingo, who made his debut<br />

in Kullark, dancer and writer<br />

Richard Walley and Steve<br />

'Baamba' Albert. O<strong>the</strong>rs, like<br />

Kelton Pell (currently per<strong>for</strong>ming<br />

nationally in Perth's Yirra Yaakin<br />

Noongar Theatre's production Solid<br />

with Ningali Law<strong>for</strong>d), are beginning<br />

to become nationally familiar. But<br />

whites have contributed too,<br />

notably <strong>the</strong> director Andrew Ross,<br />

in partnership with whom most of<br />

Davis' eight plays evolved, notably<br />

The Dreamers (1982) and No<br />

Sugar (1985). Ross founded <strong>the</strong><br />

Black Swan Theatre Company as a<br />

multi-ethnic per<strong>for</strong>mance group in<br />

Perth in 1991. Western <strong>Australia</strong>,<br />

isolated from <strong>the</strong> rest of <strong>the</strong><br />

country and with one of <strong>the</strong><br />

harshest histories of race relations,<br />

has been a major <strong>for</strong>ce in <strong>the</strong><br />

development of black actors of<br />

stature.<br />

From <strong>the</strong> Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Territory comes<br />

Roger Bennett's play about his<br />

fa<strong>the</strong>r's life as a boxer, Up <strong>the</strong><br />

Ladder (1990), which has been in<br />

<strong>the</strong> repertoire of <strong>the</strong> Melbourne<br />

Workers' Theatre since 1995 and<br />

was a success at <strong>the</strong> 1997 Festival<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Dreaming in collaboration<br />

with Brisbane's Kooemba Jdarra.<br />

His Funerals and Circuses had its<br />

premiere at <strong>the</strong> 1992 Adelaide<br />

Festival where he confronted his<br />

audience with <strong>the</strong> issue of interracial<br />

marriage (between a white<br />

policeman's daughter and a black<br />

artist). Bennett's plays and poetry<br />

were characterised by humour,<br />

music and anger at continuing<br />

discrimination against his people.<br />

He died in 1997.<br />

The struggle <strong>for</strong> self-expression has<br />

not been easy. Writing itself, Jack<br />

Davis has said, is a political act, a<br />

splitting of <strong>the</strong> mind between one's<br />

own thought and <strong>the</strong> demands of<br />

black politics. In consequence<br />

some of <strong>the</strong> early plays are<br />

didactic, and anxious in <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

choice of language. They deal<br />

again and again with <strong>the</strong> state<br />

Aboriginal Protection Acts of <strong>the</strong><br />

early part of <strong>the</strong> century which<br />

denied advancement, <strong>for</strong>ced blacks<br />

into white-governed rural ghettos<br />

and ordered that children be taken<br />

away from <strong>the</strong>ir parents and taught<br />

assimilation. O<strong>the</strong>r common<br />

<strong>the</strong>mes are job discrimination, land<br />

rights and <strong>the</strong> high incidence of<br />

black deaths in police custody, a<br />

phenomenon about which <strong>the</strong>re<br />

was an extensive, heated and<br />

finally fairly fruitless judicial inquiry.<br />

The deaths continue unabated.<br />

* * *<br />

Aboriginal writers and per<strong>for</strong>ming<br />

artists have arrived in <strong>the</strong> western<br />

<strong>the</strong>atre at a time when <strong>the</strong> <strong>for</strong>m is<br />

more diverse than at any o<strong>the</strong>r<br />

period in its history. Writers today<br />

are freer to choose <strong>the</strong>ir own <strong>for</strong>m<br />

than <strong>the</strong>y have ever been: <strong>the</strong> only<br />

restriction lies in <strong>the</strong> capacity of <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

peers to understand it and<br />

per<strong>for</strong>mers who can realise it. The<br />

fact that we have world-class young<br />

actors today like Bradley Byquar,<br />

David Ngoombujarra, Ningali<br />

Law<strong>for</strong>d, Rachel Maza, Deborah<br />

Mailman, Lydia Miller, Leah Purcell,<br />

Kylie Belling, Deborah Cheetham,<br />

Kevin Smith, Margaret Harvey and<br />

Lafe Charlton working with major<br />

companies and directors like Wesley<br />

Enoch and Noel C Tovey, is an<br />

important witness to <strong>the</strong> rate at<br />

which we are putting aside <strong>the</strong><br />

imitative skills of <strong>the</strong> past in favour<br />

of something more recognisably our<br />

own. The progress of Aboriginal<br />

writing <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> <strong>the</strong>atre has in <strong>the</strong> 90s<br />

discarded polemic <strong>for</strong> a deeper<br />

psychology. The plays have become<br />

more concerned with <strong>the</strong> emotional<br />

and spiritual life of <strong>the</strong> characters,<br />

more confidently experimental in<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir structure, and more inclined to<br />

include <strong>the</strong> white man and woman<br />

in <strong>the</strong>ir view of world. Eva Johnson's<br />

powerful solo per<strong>for</strong>mance What Do<br />

They Call Me? (1990) is a three-part<br />

monologue by Connie Brumbie,<br />

thrown into gaol <strong>for</strong> drunkenness,<br />

mourning <strong>the</strong> children who were<br />

taken from her in <strong>the</strong> 50s under <strong>the</strong><br />

Aboriginal protection legislation; her<br />

daughters Regina, now a middleclass<br />

married woman brought up<br />

unaware of her aboriginality; and<br />

Alison, now a social worker, activist<br />

and lesbian, who seeks to reconcile<br />

<strong>the</strong> family to each o<strong>the</strong>r and <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

past.<br />

One of <strong>the</strong> first plays to successfully<br />

create rounded white characters<br />

was Sally Morgan's Sistergirl<br />

(1993), about <strong>the</strong> friendship of two<br />

women, one black, one white, in an<br />

alcoholics' ward. The play toured<br />

nationally from Perth in 1993. Sadly,<br />

death dogged <strong>the</strong> cast and <strong>the</strong><br />

season ended abruptly in<br />

Melbourne and <strong>the</strong> text was<br />

suppressed by <strong>the</strong> author as a<br />

mark of respect.<br />

Ningali Law<strong>for</strong>d's solo show Ningali<br />

(created in collaboration with Robyn<br />

Archer and Angela Chaplin) was<br />

per<strong>for</strong>med all over <strong>the</strong> world in <strong>the</strong><br />

1990s. In it she tells <strong>the</strong> story of her<br />

untroubled childhood in <strong>the</strong><br />

Kimberleys, <strong>the</strong> loneliness of a city<br />

boarding school, an extraordinary<br />

six months as an exchange student<br />

in Alaska, <strong>the</strong> rebellion and trauma<br />

of adolescence and racist<br />

encounters, and <strong>the</strong> rediscovery of<br />

herself through dance and <strong>the</strong><br />

emergence of a strong maturity.<br />

More than <strong>the</strong> men, <strong>the</strong>se women<br />

have used per<strong>for</strong>mance to focus<br />

upon <strong>the</strong> healing process; <strong>the</strong>y<br />

have given <strong>the</strong>ir audiences lasting<br />

images of power. Two fur<strong>the</strong>r solo<br />

works—part political, part<br />

confessional—which celebrate <strong>the</strong><br />

inner strength of <strong>the</strong>ir remarkable<br />

per<strong>for</strong>mers, have followed Law<strong>for</strong>d<br />

to international acclaim. They are<br />

Leah Purcell's Box <strong>the</strong> Pony<br />

(written with Scott Rankin) and<br />

Deborah Cheetham's White Baptist<br />

ABBA Fan. Deborah Mailman,<br />

whose work 7 Stages of Grieving,<br />

created with director Wesley Enoch<br />

<strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> Kooemba Jdarra Indigenous<br />

Per<strong>for</strong>ming <strong>Arts</strong> Company in<br />

Brisbane, has also been around <strong>the</strong><br />

world. This is <strong>the</strong> most innovative in<br />

structure of all <strong>the</strong> works so far<br />

created. It is written in 18 scenes, in<br />

a free-verse <strong>for</strong>m incorporating<br />

enactments and film images, a<br />

variety of storytelling <strong>for</strong>ms and<br />

symbolism.<br />

The most recent black playwright<br />

to come to national attention is<br />

John Harding, whose play Up <strong>the</strong><br />

Road was first presented by <strong>the</strong><br />

Ilbijerri Aboriginal and Torres Strait<br />

Islander Theatre Cooperative in<br />

Melbourne in 1991. It was fur<strong>the</strong>r<br />

developed by <strong>the</strong> director Neil<br />

Armfield in 1997 <strong>for</strong> seasons at<br />

Melbourne's Playbox Theatre and<br />

Belvoir Street Theatre in Sydney.<br />

Harding's protagonist is, <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

first time, a middle-class Aboriginal,<br />

Ian Sampson, a Canberra<br />

bureaucrat who returns to his<br />

home town after a decade <strong>for</strong> a<br />

family funeral. There he faces not<br />

only punishment by <strong>the</strong> woman<br />

and now-dead bro<strong>the</strong>r he<br />

deserted, but finds himself <strong>the</strong><br />

centre of conflict over government<br />

policy and local affairs. Jane<br />

Harrison's Stolen (1998) was a joint<br />

production by Ilbijerri and Playbox<br />

Theatre in Melbourne. In 1999 it<br />

was revived, toured to Sydney and<br />

<strong>the</strong>n to London, where it was<br />

warmly received as part of <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>Australia</strong> <strong>Council</strong>’s HeadsUp<br />

<strong>Australia</strong>n <strong>Arts</strong> 100 festival<br />

commemorating <strong>the</strong> centenary of<br />

<strong>the</strong> act to create an <strong>Australia</strong>n

Aliwa, Yirra Yaakin Noongar Theatre<br />

Federation. Stolen, again, is a<br />

powerful combination of <strong>the</strong><br />

personal and <strong>the</strong> political as it tells<br />

<strong>the</strong> stories, in direct unvarnished<br />

terms, of five Aboriginal children<br />

<strong>for</strong>cibly removed from <strong>the</strong>ir families<br />

by government order. The<br />

production by Wesley Enoch was<br />

particularly distinctive—adding to<br />

<strong>the</strong> play's political statement <strong>the</strong><br />

actors stepped out of <strong>the</strong>ir roles at<br />

<strong>the</strong> end of <strong>the</strong> per<strong>for</strong>mance to tell<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir own stories.<br />

The plays continue to be written,<br />

and within <strong>the</strong>m <strong>the</strong> concealed<br />

history of race relations and <strong>the</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong>mes of reconciliation,<br />

empowerment and, more recently,<br />

a closer self-examination. They will<br />

continue to make an important<br />

contribution to a greater mutual<br />

understanding and respect; and<br />

especially a recognition of two<br />

realities, black and white; and <strong>the</strong><br />

values of that world which created<br />

<strong>the</strong>m.<br />

Katharine Brisbane AM, Hon.DLitt,<br />

Publisher, Currency Press.<br />

This essay has been edited from,<br />

"The Future in Black and White:<br />

Aboriginality in Recent <strong>Australia</strong>n<br />

Drama", AULLA (American<br />

Universities Language and<br />

Literature Association) Conference,<br />

Vasser College, Poughkeepsie, New<br />

York State, USA, 1994; IDEA<br />

(International Drama Education<br />

Association) Conference in<br />

Brisbane, 1994. The full version,<br />

updated from time to time, is<br />

available on <strong>the</strong> Currency Press<br />

website<br />

(www.currencypress.com.au) and in<br />

booklet <strong>for</strong>m <strong>for</strong> teachers. Excerpt<br />

from Bran Nue Day reproduced<br />

with permission.<br />

References<br />

Penny Van Toorn, "Indigenous texts<br />

and narratives," and May Britt<br />

Akerholt, "New stages:<br />

contemporary <strong>the</strong>atre" in Elizabeth<br />

Webby ed, The Cambridge<br />

Companion to <strong>Australia</strong>n Literature,<br />

Cambridge University Press,<br />

Cambridge 2000<br />

Philip Parsons, General Editor,<br />

Companion to Theatre in <strong>Australia</strong>,<br />

Currency Press, Sydney 1995<br />

Jimmy Chi & Kuckles, Bran Nue<br />

Dae, Currency Press & Magabala<br />

Books, Sydney and Broome, 1991<br />

Wesley Enoch & Deborah Mailman,<br />

7 Stages of Grieving, Playlab Press,<br />

Brisbane, 1997<br />

Anthology, Plays from Black<br />

<strong>Australia</strong>, Currency Press, Sydney<br />

1989. Contains Jack Davis, The<br />

Dreamers; Eva Johnson, Murras;<br />

Bob Maza, The Keepers; Richard<br />

Walley, Coordah.<br />

Currency Press publishes an<br />

extensive list of plays by Aboriginal<br />

writers including: Roger Bennett,<br />

Jimmy Chi, Jack Davis, Kevin<br />

Gilbert, Eva Johnson, Robert J<br />

Merritt and John Harding.<br />

7

8<br />

Yirra Yaakin Noongar Theatre<br />

Solid<br />

This play tells <strong>the</strong> story of Graham,<br />

a Noongar from <strong>the</strong> suburbs of<br />

Perth who heads north to escape<br />

drugs, unemployment and personal<br />

tragedy. On <strong>the</strong> road to Fitzroy<br />

Crossing he meets Carol, a<br />

Kimberley woman returning home<br />

after a long absence in <strong>the</strong> city to<br />

face <strong>the</strong> traditional law from which<br />

she has been running. Two<br />

Aboriginal people from Perth but<br />

from different worlds, both looking<br />

<strong>for</strong> something new. Starring Ningali<br />

Law<strong>for</strong>d and Kelton Pell.<br />

...two of <strong>the</strong> best young <strong>Australia</strong>n actors of<br />

<strong>the</strong>ir generation. The <strong>Australia</strong>n<br />

Aliwa<br />

When <strong>the</strong> Welfare came sniffin'<br />

around wanting to take <strong>the</strong> kids<br />

away, <strong>the</strong>ir Mum took <strong>the</strong> hard road<br />

and left her house and community<br />

to keep <strong>the</strong> family toge<strong>the</strong>r. Almost<br />

fifty years later, her three daughters<br />

Dot, E<strong>the</strong>l and Judith tell a story of<br />

love and survival in a very special<br />

family.<br />

Yirra Yaakin has crafted a fine<br />

piece of <strong>the</strong>atre, as moving as it<br />

is uplifting....a triumphantly<br />

gentle piece of <strong>the</strong>atre.<br />

The West <strong>Australia</strong>n<br />

Yirra Yaakin is one of <strong>Australia</strong>'s<br />

leading Aboriginal <strong>the</strong>atre<br />

companies. Based in Perth,<br />

Western <strong>Australia</strong> in <strong>the</strong> heart of <strong>the</strong><br />

Noongar Nation, Yirra Yaakin's<br />

commitment and energy has<br />

inspired an active and diverse range<br />

of <strong>the</strong>atrical, educational and<br />

developmental projects, providing<br />

<strong>the</strong> basis <strong>for</strong> a growing world-class,<br />

professional arts company. Yirra<br />

Yaakin was <strong>the</strong> recipient of <strong>the</strong><br />

Prince Charles Trophy <strong>for</strong> services<br />

to <strong>the</strong> community in 1997.

Kooemba Jdarra Indigenous<br />

Per<strong>for</strong>ming <strong>Arts</strong><br />

Goin' to <strong>the</strong> Island<br />

After seven years on <strong>the</strong> mainland,<br />

TJ, a young Murri ho<strong>the</strong>ad returns<br />

home to Minjerribah (Stradbroke<br />

Island) to celebrate his 21st<br />

birthday. To his surprise his views<br />

about sand mining, tourism and <strong>the</strong><br />

cultural revival of his people are<br />

challenged by his extended family.<br />

Therese Collie's play uses humour<br />

as well as dance and musical<br />

<strong>for</strong>ms that range from traditional to<br />

reggae and rap. TJ's family chart<br />

<strong>the</strong> Island's comings and goings<br />

from <strong>the</strong> dreaming to <strong>the</strong> present<br />

day to help <strong>the</strong> young man to<br />

understand <strong>the</strong> strong ancestral<br />

and communal ties that keep him<br />

goin' to <strong>the</strong> island.<br />

In its generosity of spirit and its<br />

powerful <strong>the</strong>atricality, this is a<br />

play which will delight Murris and<br />

whitefellas alike.<br />

Brisbane Courier Mail.<br />

Paradoxes perplex and unsettle<br />

as <strong>the</strong>y jangle <strong>the</strong> expected with<br />

<strong>the</strong> unexpected to create untried<br />

symbols and unanticipated<br />

meanings. RealTime<br />

Acknowledged as <strong>Australia</strong>'s <strong>for</strong>e-<br />

most Indigenous <strong>the</strong>atre company,<br />

Kooemba Jdarra is committed to<br />

producing professional innovative<br />

Indigenous <strong>the</strong>atre that continues<br />

<strong>the</strong> tradition of storytelling by<br />

engaging with new <strong>for</strong>ms of<br />

expression. At <strong>the</strong> same time <strong>the</strong><br />

company provides opportunities <strong>for</strong><br />

Indigenous artists to present <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

perspectives and have a voice.<br />

The program includes mainstage<br />

productions, workshops, touring<br />

and regional programs, community<br />

cultural development and<br />

awareness through training <strong>for</strong> new<br />

and emerging Indigenous artists<br />

and artsworkers.<br />

Ilbijerri Aboriginal & Torres Strait<br />

Islander Theatre Co-operative<br />

Stolen<br />

Developed by <strong>the</strong> company in<br />

collaboration with Playbox Theatre,<br />

Jane Harrison's play confronts <strong>the</strong><br />

ugly history of so-called 'integration'<br />

policies under which successive<br />

<strong>Australia</strong>n governments took<br />

Aboriginal children from <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

families so that <strong>the</strong>y could be raised<br />

in white-run institutions. The work<br />

developed in consultation with <strong>the</strong><br />

Victorian Indigenous community,<br />

has been written by an Aboriginal<br />

playwright and per<strong>for</strong>med by<br />

Indigenous actors. Through <strong>the</strong><br />

stories of five Koori children<br />

struggling to survive in a society<br />

intent on destroying <strong>the</strong>ir culture<br />

and <strong>the</strong>ir identity, Stolen brings to<br />

vivid life <strong>the</strong> complex and<br />

controversial issues surrounding <strong>the</strong><br />

Stolen Generations.<br />

In 1990 a group of Indigenous<br />

artists and community members<br />

came toge<strong>the</strong>r to <strong>for</strong>m a<br />

professional <strong>the</strong>atre company <strong>for</strong><br />

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander<br />

people of Victoria. Since <strong>the</strong>n <strong>the</strong><br />

company has initiated and<br />

developed per<strong>for</strong>mances in<br />

collaboration with <strong>the</strong>ir community.<br />

In addition to workshops and<br />

playreadings, <strong>the</strong>y have produced<br />

two important works—Up <strong>the</strong> Road<br />

by John Harding, which had<br />

seasons in Melbourne and Sydney<br />

in 1991, and Stolen in 1998. Both<br />

<strong>the</strong>se plays explore complex and<br />

controversial issues from an<br />

Indigenous perspective <strong>for</strong><br />

Indigenous and non-indigenous<br />

audiences.<br />

Per<strong>for</strong>mers: Tammy Anderson, a<br />

Moonbird woman, Flinders Island<br />

mob in Tasmania; Kylie Belling,<br />

Yorta Yorta/Wiradjuri; Glenn Shea,<br />

Wathaurong/Ngarrindjeri; LeRoy<br />

Parsons, South Coast NSW;<br />

Pauline Whyman, a Riverwoman;<br />

Director, Wesley Enoch, Stradbroke<br />

Island.<br />

Following seasons in Melbourne<br />

and Sydney, Stolen had a very<br />

successful tour to London in 2000<br />

as part of <strong>the</strong> <strong>Australia</strong> <strong>Council</strong>’s<br />

HeadsUp <strong>Australia</strong>n <strong>Arts</strong> 100<br />

festival celebrating <strong>Australia</strong>'s<br />

Centenary of Federation.<br />

Stolen is extraordinary ... a restless, time-transcending mosaic,<br />

dazzlingly realised in Wesley Enoch's production ... as moving as any<br />

production in London. Michael Billington, The Guardian.<br />

9

10<br />

Wesley Enoch and Deborah<br />

Mailman / Kooemba Jdarra<br />

The 7 Stages of Grieving<br />

Originally conceived, co-written and<br />

directed in Brisbane in 1995 by<br />

Kooemba Jdarra's <strong>the</strong>n Artistic<br />

Director Wesley Enoch, The 7<br />

Stages of Grieving is a solo<br />

per<strong>for</strong>mance co-written and<br />

per<strong>for</strong>med by Murri artist, Deborah<br />

Mailman, one of <strong>Australia</strong>'s most<br />

accomplished actors of stage and<br />

screen, with images created <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

production by noted visual artist<br />

Leah King-Smith.<br />

7 Stages is an important<br />

contemporary per<strong>for</strong>mance work.<br />

Deborah Mailman tells a collective<br />

story which merges personal family<br />

history with instances of public<br />

grief. The work has toured <strong>Australia</strong><br />

and internationally to considerable<br />

acclaim.<br />

Nura Ward, Nellie Patterson,<br />

Fiona Foley, Heidrun Löhr and<br />

Aku Kadogo<br />

Ochre and Dust<br />

A per<strong>for</strong>mance in an installation<br />

The installation created by Batjala<br />

artist Fiona Foley combined with<br />

Heirun Löhr's monochrome and<br />

colour photographs, provides an<br />

evocative stage setting <strong>for</strong> two<br />

Anangu-Pitjantjatjara storytellers.<br />

Nura Ward and Nellie Patterson are<br />

senior law women and ambassadors<br />

<strong>for</strong> Anangu-Pitjantjatjara culture.<br />

These dynamic women recount<br />

tales of <strong>the</strong>ir lives and <strong>the</strong>ir Tjukurpa<br />

(sacred stories or law that created<br />

and governs <strong>the</strong> world). The nature<br />

of this work at once provides a<br />

soundscape and photo journey<br />

through <strong>the</strong> Pitjantjatjara homelands<br />

as well as an interactive backdrop<br />

<strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> storytellers. This<br />

collaborative impression of Central<br />

<strong>Australia</strong> conceived by Aku Kadogo<br />

pays homage to <strong>the</strong> ongoing<br />

relationship she has with Anangu.<br />

Ochre and Dust was produced <strong>for</strong><br />

<strong>the</strong> Perth International and <strong>the</strong> 2000<br />

Telstra Adelaide Festivals.<br />

8th Festival of Pacific <strong>Arts</strong>, 2000<br />

Mailman is a wonderfully open per<strong>for</strong>mer… she manages to suggest<br />

<strong>the</strong> whole history of <strong>the</strong> invasion of her country...through a mix of<br />

reminiscense, great comedy, passionate statement and vivid<br />

<strong>the</strong>atricality The <strong>Australia</strong>n

Black Swan Theatre Company<br />

Bidenjarreb Pinjarra<br />

West <strong>Australia</strong>n Noongar Aboriginal<br />

actors, Kelton Pell and Trevor Parfitt<br />

researched, improvised and shaped<br />

<strong>the</strong> story of The Battle of Pinjarra in<br />

partnership with whitefellas Geoff<br />

Kelso and Phil Thomson. This latest<br />

version is presented with <strong>the</strong> cross<br />

cultural, Perth-based Black Swan<br />

Theatre Company which has had<br />

an ongoing association with<br />

Indigenous artists.<br />

The quartet has produced a<br />

compelling <strong>the</strong>atrical work that<br />

shakes up traditionally held views<br />

of history and discovers clues to<br />

what really happened in 1834 when<br />

Governor James Stirling led an<br />

armed expedition into <strong>the</strong> territory<br />

of <strong>the</strong> Murray River people, 90<br />

kilometres south of <strong>the</strong> struggling<br />

Swan River Colony in Western<br />

<strong>Australia</strong>.<br />

Bidenjarreb Pinjarra, says Kelton<br />

Pell, is "a story about a crucial<br />

moment in Noongar history which<br />

honours <strong>the</strong> fallen and sets <strong>the</strong> facts<br />

straight", told through satire, mime,<br />

improvised comedy, dramatic<br />

conflict and tough physical <strong>the</strong>atre."<br />

The play had two seasons in Perth,<br />

a tour of south-west <strong>Australia</strong>,<br />

Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Territory, Melbourne and<br />

Sydney. In 2000 Black Swan will<br />

undertake a regional tour of <strong>the</strong><br />

work.<br />

There is a wonderful fusion of<br />

comic (and <strong>the</strong> comic is very<br />

funny) with <strong>the</strong> tragic in <strong>the</strong> way<br />

<strong>the</strong>y tell it ... a wonderful mix of<br />

wisdom about how life is lived,<br />

Bidenjarreb Pinjarra tells us about<br />

our past. And we grieve. But <strong>the</strong>n<br />

offers us a powerful paradigm <strong>for</strong><br />

our future. And we hope.<br />

Sydney Morning Herald<br />

REM Theatre<br />

toteMMusic<br />

In this collaboration between<br />

Indigenous and non-indigenous<br />

artists, a young city dweller is<br />

introduced to <strong>the</strong> spirit and dances<br />

of her people by <strong>the</strong> visit of <strong>the</strong><br />

Kangaroo Man. toteMMusic<br />

explores <strong>the</strong> balance between<br />

traditional and contemporary<br />

<strong>Australia</strong>n society. The work<br />

premiered at <strong>the</strong> Lucerne<br />

International Music Festival followed<br />

by per<strong>for</strong>mances at <strong>the</strong> Flanders<br />

Festival, Ghent, and <strong>the</strong> Zuiderpers<br />

Huis, Antwerp. It was included in<br />

<strong>the</strong> Spotlight Program, 4th<br />

<strong>Australia</strong>n Per<strong>for</strong>ming <strong>Arts</strong> Market,<br />

Adelaide 2000.<br />

The per<strong>for</strong>mers are drawn from <strong>the</strong><br />

Torres Strait in <strong>the</strong> north, through<br />

Tennant Creek in <strong>the</strong> Central Desert,<br />

to Western <strong>Australia</strong>. REM integrates<br />

<strong>the</strong> per<strong>for</strong>ming arts into a vibrant,<br />

cross-cultural, cross-art<strong>for</strong>m <strong>the</strong>atre<br />

and deals simply with concepts and<br />

attitudes that both children and<br />

adults relate to and understand.<br />

Queensland Theatre Company<br />

The Sunshine Club<br />

Frank, an Aboriginal serviceman,<br />

comes home from World War II to<br />

find that although <strong>the</strong> wider world<br />

may have changed, not much is<br />

different <strong>for</strong> him. Harassed by<br />

police, barred from hotels and<br />

<strong>for</strong>bidden from dancing with his<br />

childhood friend, Rose—<strong>the</strong> white<br />

minister's daughter—Frank decides<br />

to take action. With his friends and<br />

family he sets up The Sunshine<br />

Club, a place where white and black<br />

can meet and, above all, dance.<br />

Commissioned by <strong>the</strong> Queensland<br />

Theatre Company, book, lyrics and<br />

direction are by Wesley Enoch,<br />

music by John Rodgers and<br />

featuring a cast of powerful<br />

Indigenous per<strong>for</strong>mers. The<br />

premiere season included Cairns,<br />

Townsville, Mackay, Brisbane and<br />

subsequently <strong>the</strong> launch of <strong>the</strong><br />

Sydney Theatre Company's 2000<br />

program.<br />

...with a heart and a brain, a<br />

compelling, important take on<br />

<strong>the</strong> musical.<br />

Sydney Morning Herald<br />

11

12<br />

The Marrugeku Company<br />

Crying Baby<br />

Founded in 1994 specifically <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong><br />

project, Mimi, Marrugeku comprises<br />

Western <strong>Australia</strong>n urban<br />

Indigenous dancers and musicians,<br />

non-indigenous physical <strong>the</strong>atre<br />

practitioners from Stalker Theatre in<br />

Sydney and Kunwinjkju dancers—<br />

story tellers and musicians from<br />

Kunbarllanjnja, a remote community<br />

in Arnhem Land. Marrugeku's Mimi<br />

was extraordinarily successful,<br />

playing in urban <strong>Australia</strong>n arts<br />

festivals, remote Aboriginal<br />

communities and international arts<br />

festivals.<br />

Crying Baby is a large scale<br />

outdoor intercultural per<strong>for</strong>mance<br />

incorporating stilts and aerial work,<br />

contemporary Indigenous dance<br />

and music, installation, weaving,<br />

film and contemporary sound art.<br />

Blurring <strong>the</strong> edges between story,<br />

history and Djang (or dreaming), its<br />

focus is on stories from post<br />

contact/colonial times as well as<br />

modern life <strong>for</strong> Indigenous<br />

<strong>Australia</strong>ns living in remote<br />

communities.<br />

Key artists include director Rachael<br />

Swain, choreographer Raymond<br />

Blanco, visual artist Thompson<br />

Yulidjirri, musical director Mat<strong>the</strong>w<br />

Fargher, designer Andrew Carter,<br />

weaver Yvonne Koolmatrie, film<br />

director Warwick Thornton. Crying<br />

Baby premieres as a work in<br />

progress at <strong>the</strong> Darwin Festival<br />

2000 and in its final <strong>for</strong>m at <strong>the</strong><br />

Festival of Perth 2001.<br />

A stage beneath <strong>the</strong> stars of<br />

Arnhem Land; an ancient rock<br />

face <strong>for</strong> a backdrop, lit by<br />

flickering, dancing light; an<br />

ecstasy of voices, of Aboriginal<br />

tales and chants; a cast of<br />

dancers, actors, trapeze-tumblers<br />

and stilt walkers, per<strong>for</strong>ming<br />

against projected video images,<br />

banks of TVs and satellite dishes;<br />

a drama unfolding at once on<br />

triple interwoven levels, full of<br />

half-buried symbols, rhymes and<br />

parallels. Such is <strong>the</strong> spectacle of<br />

Crying Baby, <strong>the</strong> remarkable new<br />

production of <strong>the</strong> Marrugeku<br />

Company and <strong>the</strong> piece de<br />

resistance of this year's Darwin<br />

Festival.<br />

The <strong>Australia</strong>n<br />

Leah Purcell<br />

Box <strong>the</strong> Pony<br />

Box <strong>the</strong> Pony, a semi-factual<br />

acccount of Leah Purcell's life, was<br />

<strong>the</strong> smash hit of <strong>the</strong> 1997 Olympic<br />

<strong>Arts</strong> Festival's Festival of <strong>the</strong><br />

Dreaming and was critically<br />

acclaimed at <strong>the</strong> 1998 Adelaide and<br />

1999 Edinburgh <strong>Arts</strong> Festivals.<br />

Subsequent seasons were<br />

successfuly staged in Sydney and<br />

Brisbane. At <strong>the</strong> Sydney Opera<br />

House it was part of <strong>the</strong><br />

Reconciliation celebrations in 2000.<br />

The work was included in <strong>the</strong><br />

HeadsUp <strong>Australia</strong>n <strong>Arts</strong> 100<br />

festival at <strong>the</strong> Barbican in London,<br />

July 2000.<br />

Leah Purcell (Nation; Waka Waka)<br />

comes from a long line of<br />

vaudevillians. In 1993 she was cast<br />

in Jimmy Chi's ground breaking<br />

musical, Bran Nue Dae, which toured<br />

<strong>Australia</strong>. She appeared in <strong>the</strong>atre<br />

works at Brisbane's La Bôite and<br />

<strong>the</strong>n moved to Sydney to work as a<br />

television presenter. Leah is an official<br />

Ambassador <strong>for</strong> Reconciliation<br />

through her music and guest<br />

speaking appearances. In 1999 she<br />

was voted Best Female Artist at <strong>the</strong><br />

National indigenous Awards. She<br />

received accolades <strong>for</strong> her<br />

appearance in Belvoir Street<br />

Theatre's production of The Marriage<br />

of Figaro as part of <strong>the</strong> Olympics <strong>Arts</strong><br />

Festival in Sydney in 2000.<br />

While she doesn't shirk from plumbing <strong>the</strong> depths of her early mis<strong>for</strong>tune,<br />

overall <strong>the</strong> play is raw, cheeky, celebratory and very funny.<br />

Sydney Morning Herald

Deborah Cheetham<br />

White Baptist ABBA Fan<br />

This is a moving, funny and<br />

<strong>for</strong>thright per<strong>for</strong>mance based on<br />

incidents from <strong>the</strong> life of Aboriginal<br />

opera singer, Deborah Cheetham.<br />

From <strong>for</strong>ced removal from her<br />

Aboriginal family to her upbringing<br />

in <strong>the</strong> strict confines of a white<br />

Baptist family, to her eventual<br />

reunion thirty years later with her<br />

birth mo<strong>the</strong>r, Deborah Cheetham<br />

weaves events from her life with<br />

songs by Saint Saens, Catalanni<br />

and Dvorak as her intimate story<br />

unfolds. Commissioned <strong>for</strong> The<br />

1997 Olympics <strong>Arts</strong> Festival’s<br />

Festival of <strong>the</strong> Dreaming, and<br />

produced by Per<strong>for</strong>ming Lines, <strong>the</strong><br />

work's many seasons have<br />

included <strong>the</strong> Christchurch <strong>Arts</strong><br />

Festival and <strong>the</strong> Edge, Auckland<br />

(New Zealand) and sell-out houses<br />

<strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> Zuercher Theatre Spectakl,<br />

Zurich, 1999. The work was<br />

included in <strong>the</strong> Barbican season of<br />

<strong>the</strong> HeadsUp <strong>Australia</strong>n <strong>Arts</strong> 100<br />

festival in London, 2000.<br />

...with bitter irony, seldom<br />

sentimental, her witty torrent of<br />

words fascinate <strong>the</strong> audience.<br />

Solothurner Zeitung, Zurich.<br />

Tom E Lewis and Handspan<br />

Visual Theatre<br />

Lift 'Em Up Socks<br />

Tom E Lewis (Warndarrung-Marra,<br />

born Ngukurr) began his career in<br />

film and TV. Subsequently he<br />

per<strong>for</strong>med in <strong>the</strong>atre productions as<br />

well as devising a solo<br />

per<strong>for</strong>mance, Thumbul. His musical<br />

career has taken him all over <strong>the</strong><br />

world with <strong>the</strong> George Dreyfus<br />

Sextet, <strong>the</strong> Lewis and Young Jazz<br />

duo and The Anthropologists. The<br />

reputation of <strong>the</strong> non-indigenous<br />

Handspan is built on innovation in<br />

<strong>for</strong>m, technique and content. The<br />

company has undertaken 16<br />

international tours to 29 festivals<br />

and events worldwide and in 1994<br />

won <strong>the</strong> prestigious UNESCO<br />

Award <strong>for</strong> "outstanding contribution<br />

to <strong>the</strong> arts."<br />

Lift 'Em Up Socks began with a<br />

collection of marionettes loaned to<br />

Lewis <strong>for</strong> restoration. Amongst <strong>the</strong><br />

usual European folk tale characters<br />

were three <strong>Australia</strong>ns including a<br />

small Aboriginal boy. Tom E Lewis<br />

per<strong>for</strong>ms with Rod Primrose,<br />

directed by David Bell with<br />

puppetry direction by Hea<strong>the</strong>r<br />

Monk.<br />

It's like learning to understand a<br />

new symbolism that converts<br />

time, <strong>for</strong> example, into static,<br />

visual symbols. It is a show best<br />

enjoyed by allowing <strong>the</strong> many<br />

suggestive words and images to<br />

work associatively.<br />

The Age<br />

13

14<br />

dance<br />

Indigenous dance: The place, not <strong>the</strong> space<br />

Contemporary <strong>Australia</strong>n<br />

Indigenous dance has reached new<br />

heights of international recognition<br />

in <strong>the</strong> last five years. This has been<br />

spear-headed by <strong>the</strong> critical and<br />

popular success of Bangarra Dance<br />

Theatre under <strong>the</strong> artistic direction<br />

of Stephen Page. Bangarra's<br />

success has strong links with <strong>the</strong><br />

25 year history of <strong>the</strong> National<br />

Aboriginal & Islander Skills<br />

Development Association (NAISDA)<br />

where most of Bangarra's dancers<br />

trained, and Aboriginal Islander<br />

Dance Theatre (AIDT), <strong>the</strong> professional<br />

company associated with<br />

NAISDA and headed by Raymond<br />

Blanco which preceded Bangarra.<br />

Choreographers connected with<br />

<strong>the</strong>se institutions at different times<br />

have included Mat<strong>the</strong>w Doyle,<br />

Monica Stevens, Marilyn Miller,<br />

Albert David, Bernadette Walong<br />

and Frances Rings.<br />

The foundation <strong>for</strong> contemporary<br />

Indigenous dance is firmly based in<br />

an ancient and evolving dance<br />

tradition which is part of <strong>the</strong> spiritual<br />

life of <strong>Australia</strong>n Aboriginal people. It<br />

is important, however, to understand<br />

that it is not one tradition, it is<br />

many, and that <strong>the</strong> dances are as<br />

diverse as <strong>the</strong> numerous language<br />

and regional groups that make up<br />

<strong>Australia</strong>n Aboriginal culture.<br />

Different styles of dancing express<br />

different narratives in very different<br />

landscapes and constitute a rich<br />

source of inspiration and meaning<br />

<strong>for</strong> contemporary dance and its<br />

interplay of aes<strong>the</strong>tic and spiritual<br />

concerns.<br />

The dances of <strong>the</strong>se communities<br />

are increasingly being per<strong>for</strong>med by<br />

cultural groups who travel within<br />

<strong>Australia</strong> and throughout <strong>the</strong> world.<br />

The Doonooch Dancers, based in<br />

<strong>the</strong> Shoalhaven region of <strong>the</strong> South<br />

Coast of New South Wales, and <strong>the</strong><br />

Torres Strait Island Cultural Group,<br />

both appearing at <strong>the</strong> 8th Festival<br />

of Pacific <strong>Arts</strong>, are examples of<br />

such groups. Among <strong>the</strong> many<br />

o<strong>the</strong>rs are <strong>the</strong> Tal-Kin-Jeri Dance<br />

Group who research and per<strong>for</strong>m<br />

<strong>the</strong> dances and stories of <strong>the</strong><br />

Ngarrindjeri people of South<br />

<strong>Australia</strong>. The White Cockatoo<br />

Per<strong>for</strong>ming Group from Arnhem<br />

Land in <strong>the</strong> Nor<strong>the</strong>rn Territory are a<br />

group of senior men from several<br />

language groups sharing <strong>the</strong> same<br />

social and familial affiliations. The<br />

company has completed two world<br />

tours, recently returning from a tour<br />

to Sweden, Switzerland, Austria<br />

and Hannover, Germany where <strong>the</strong>y<br />

were part of EXPO 2000.<br />

More important than playing to<br />

international audiences is <strong>the</strong><br />

opportunity <strong>for</strong> communities to<br />

experience each o<strong>the</strong>r's dance and<br />

music and <strong>for</strong> cultural groups to<br />

per<strong>for</strong>m <strong>for</strong> Aboriginal children in<br />

schools. Many communities have<br />

lost <strong>the</strong>ir languages and <strong>the</strong>ir dances<br />

over <strong>the</strong> last two hundred years.<br />

Gurruwun Yunupingu, principal at<br />

Yirrkala School in North East<br />

Arnhem Land, talks about<br />

per<strong>for</strong>ming Yolngu music and dance<br />

in schools: "Many audiences were<br />

astonished and unsure how to react<br />

because <strong>the</strong>y had never seen or<br />

heard traditional dance and music<br />

be<strong>for</strong>e. It made many cry, <strong>for</strong> in<br />

some parts of <strong>the</strong> world some<br />

Indigenous people have lost <strong>the</strong>ir<br />

culture because of <strong>the</strong> assimilation<br />

and colonisation" ("Language and<br />

Traditional Dance Per<strong>for</strong>ming in<br />

Public Schools", Dancing comes<br />

from <strong>the</strong> land, Writings on Dance 20,<br />

2000). The Darwin-based Tracks, a<br />

dance company working closely with<br />

Indigenous people, conducts<br />

residencies in remote Aboriginal<br />

communities and regional areas to<br />

help maintain and develop dance<br />

traditions.<br />

A strong connection with tradition is<br />

found also in contemporary dance.<br />

Not only is <strong>the</strong>re a wealth of dance<br />

to draw on but also spiritual<br />

resources. Djakapurra Munyarryun<br />

is a dancer and songman with <strong>the</strong><br />

Sydney-based Bangarra Dance<br />

Theatre, He is also <strong>the</strong> company's<br />

cultural consultant, providing<br />

traditional knowledge in<br />

consultation with <strong>the</strong> elders of <strong>the</strong><br />

Munyarryun Clan in Dhälinbuy,<br />

North East Arnhem Land, where he<br />

grew up.<br />

Even with developments in touring,<br />

education and o<strong>the</strong>r assistance,<br />

Raymond Blanco worries that "a<br />

major shift toward <strong>the</strong> company<br />

<strong>for</strong>m of dance" has resulted in<br />

insufficient accommodation <strong>for</strong><br />

traditionally based Aboriginal or<br />

Torres Strait Island dancers. "This is<br />

<strong>the</strong> root from where our dance<br />

stems. It doesn't need to be dressed<br />

up and served in a certain way. It is<br />

culture and needs to be understood<br />

entirely." Marilyn Miller, dancer,<br />

choreographer and assistant to<br />

Raymond Blanco <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> Opening<br />

Ceremony of <strong>the</strong> 8th Festival of<br />

Pacific <strong>Arts</strong>, says of Blanco's years<br />

as <strong>the</strong> Artistic Director of AIDT, that<br />

"he was courageous enough to say,<br />

‘well <strong>the</strong>re are all <strong>the</strong>se different<br />

types of traditional dance—Torres<br />

Strait and numerous mainland<br />

dances’, so he always made <strong>the</strong><br />

ef<strong>for</strong>t to stage both Islander culture<br />

as well as Aboriginal culture. He<br />

staged Lardil influences and Tiwi<br />

influences and I actually thought<br />

that was ground-breaking, showing<br />

how much <strong>the</strong>re was to choose<br />

from and avoiding clichés."<br />

As in o<strong>the</strong>r art <strong>for</strong>ms, a recurrent<br />

topic of debate in dance is <strong>the</strong><br />

relationship between Indigenous and<br />

western <strong>for</strong>ms of expression, with<br />

Indigenous artists often experienced<br />

in both. Reviewers look <strong>for</strong> a<br />

syn<strong>the</strong>sis of <strong>for</strong>ms and are<br />

disappointed if <strong>the</strong>y don't see it.<br />

People wary of <strong>the</strong> dilution of<br />

tradition see Indigenous <strong>for</strong>ms as<br />

suffering cultural assimilation. Marilyn<br />

Miller describes <strong>the</strong> complexities of<br />

<strong>the</strong> engagement between<br />

Indigenous and western dance:<br />

"With traditional dancing, it all comes<br />

from <strong>the</strong> place where <strong>the</strong> people<br />

are—<strong>the</strong> geography in<strong>for</strong>ms <strong>the</strong> type<br />

of stepping that is done, and <strong>the</strong><br />

actual story and your totem’s relation<br />

to that story will determine how you<br />

actually <strong>for</strong>m <strong>the</strong> dancing.<br />

"In contrast, contemporary dance<br />

caters <strong>for</strong> <strong>the</strong> stage. That takes <strong>the</strong><br />

dance out of any real life<br />

environment—you only have to<br />

know your place on <strong>the</strong> stage. The<br />

meaning of place is so much<br />

stronger in Indigenous dance<br />

because <strong>the</strong> place where <strong>the</strong><br />

dancing is is determined by <strong>the</strong><br />

bigger event—whe<strong>the</strong>r you're<br />

dancing <strong>for</strong> a funeral or you're<br />

dancing <strong>for</strong> a change of season or a<br />

wedding. In contemporary dance it<br />

is just a matter of spacing ra<strong>the</strong>r<br />

than place. And <strong>the</strong>re are not as<br />

many guidelines <strong>for</strong> contemporary<br />

choreography, or as much meaning<br />

to <strong>the</strong> sequencing of <strong>the</strong> move-<br />

ments, or as much meaning to <strong>the</strong><br />

movements <strong>the</strong>mselves...and that’s<br />

something that I say to <strong>the</strong> younger<br />

ones—you have to know <strong>the</strong><br />

meaning behind <strong>the</strong> movements,<br />

whe<strong>the</strong>r it's traditional or contemporary,<br />

o<strong>the</strong>rwise you can’t per<strong>for</strong>m<br />

it—you're just putting it <strong>the</strong>re."<br />

Asked about <strong>the</strong> future <strong>for</strong><br />

Indigenous dance, Miller sees a<br />

significant role <strong>for</strong> NAISDA<br />