CONSERVATIVE

eurocon_13_2016_winter-spring_a

eurocon_13_2016_winter-spring_a

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Indeed, this enracinement can become a radical<br />

closing off to the koinos (the common). The idiotès can<br />

“idolize particularity to the point of loathing difference<br />

[or otherness]. This is the specific perversion of<br />

Nazism”. Because of Nazism, “Europe currently<br />

rejects with horror any idea that opposes individualism<br />

and limitless emancipation … and describes ‘identities’<br />

as fundamental human requirements”.<br />

The idiotès is highly resistant to time and<br />

space: He is both “against progress” and “against<br />

globalization and Europe”. Resentment stems<br />

from this resistance. According to the “all powerful<br />

ideology of emancipation, it is in the nature of man<br />

to deploy himself on these two levels”. But he who<br />

cannot, “cannot be happy”, she says. Delsol does not<br />

entirely dismiss this language; but she still argues that<br />

the populist is an idiotès—in the Greek sense (not an<br />

‘idiot’ in modern parlance).<br />

Nevertheless, Delsol gives more credit to the<br />

idiotès. Indeed, she says, “one cannot say, like in ancient<br />

Greece, that the popular element leans toward its own<br />

private interest, while the elite gives priority to the<br />

common interest. Everything is more complicated and<br />

is even often inverted”. In my view, we may go further<br />

than Delsol on this point: The individualism that has<br />

been promoted by liberalism decisively contributed to<br />

the destruction of the sense of responsibility among<br />

the elites. With such an ethos, it is no surprise that the<br />

elites have lost sight of the common good.<br />

From the polis to truth<br />

Delsol’s insights are remarkable. First, she says<br />

that in the “popular milieu, people believe that the<br />

citizen is not a universal individual living in some<br />

abstract country but rather a man incarnated in space<br />

and time”. These serve as “bedrocks”, she says, “on<br />

which man can lift himself up towards the common<br />

good”. At a time of “limitless emancipation”, the<br />

people can provide the elites with common sense.<br />

Thus, the former should engage with the latter, instead<br />

of insulting them. This debate should carry on in<br />

mutual respect since “none of the two tendencies—the<br />

love of our roots and the appeal of emancipation—is<br />

meant to win people over”. In Delsol’s mind, both<br />

terms are equally essential and “the West was created<br />

with emancipation as a new dogma”. She concludes<br />

that “[a] well-ordered political regime should “educate<br />

people to work towards emancipation and educate<br />

the elites to work towards enracinement—giving to<br />

both what they lack”. Such a regime could do this, for<br />

instance, “by convincing people of the barbarism of<br />

the death penalty”.<br />

All this requires that people seek the truth in the<br />

manner of the Greeks—that is, without ideology. In<br />

this way, it becomes a personal and philosophical quest,<br />

rather than a collective and political one. All political<br />

communities are by their nature particular. Because<br />

the absolute is always hard (if not impossible) to reach,<br />

intellectuals should make an effort not to give in to<br />

an excess of emancipation. One should realize that<br />

particularisms can point towards universal truth—and<br />

that citizens should devote themselves to the good of<br />

their own political community. In this, Delsol, who<br />

explores all these ideas with verve and nuance, is an<br />

excellent guide.<br />

Edouard Chanot is the Director of the Institut Clisthène in<br />

Paris and a Ph.D. candidate in Political Science.<br />

A. SAVIN / CCA-SA 3.0<br />

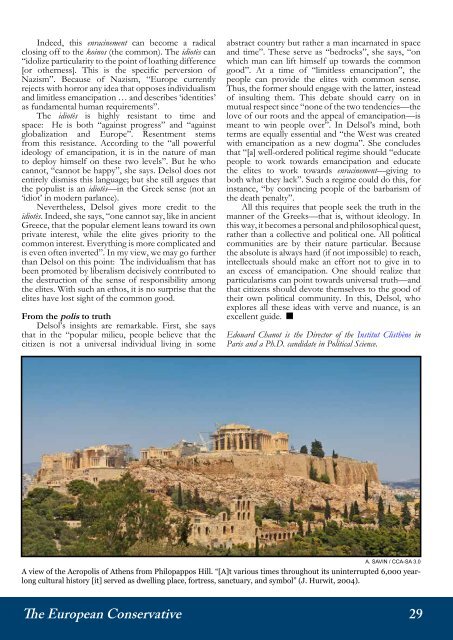

A view of the Acropolis of Athens from Philopappos Hill. “[A]t various times throughout its uninterrupted 6,000 yearlong<br />

cultural history [it] served as dwelling place, fortress, sanctuary, and symbol” (J. Hurwit, 2004).<br />

The European Conservative 29