Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

CINEMA<br />

....................................<br />

The Moon and the Sledgehammer<br />

Field of dreamers<br />

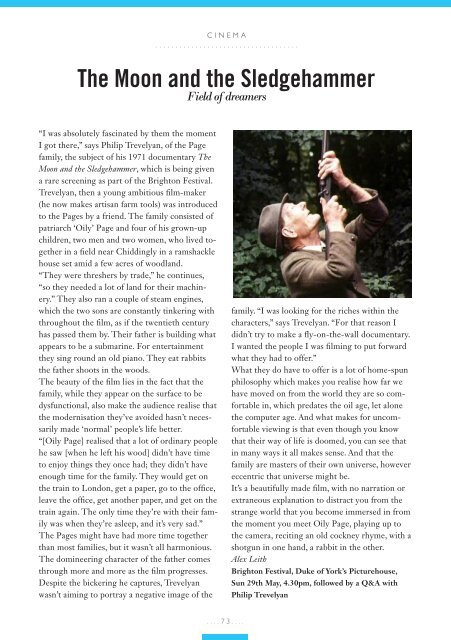

“I was absolutely fascinated by them the moment<br />

I got there,” says Philip Trevelyan, of the Page<br />

family, the subject of his 1971 documentary The<br />

Moon and the Sledgehammer, which is being given<br />

a rare screening as part of the <strong>Brighton</strong> Festival.<br />

Trevelyan, then a young ambitious film-maker<br />

(he now makes artisan farm tools) was introduced<br />

to the Pages by a friend. The family consisted of<br />

patriarch ‘Oily’ Page and four of his grown-up<br />

children, two men and two women, who lived together<br />

in a field near Chiddingly in a ramshackle<br />

house set amid a few acres of woodland.<br />

“They were threshers by trade,” he continues,<br />

“so they needed a lot of land for their machinery.”<br />

They also ran a couple of steam engines,<br />

which the two sons are constantly tinkering with<br />

throughout the film, as if the twentieth century<br />

has passed them by. Their father is building what<br />

appears to be a submarine. For entertainment<br />

they sing round an old piano. They eat rabbits<br />

the father shoots in the woods.<br />

The beauty of the film lies in the fact that the<br />

family, while they appear on the surface to be<br />

dysfunctional, also make the audience realise that<br />

the modernisation they’ve avoided hasn’t necessarily<br />

made ‘normal’ people’s life better.<br />

“[Oily Page] realised that a lot of ordinary people<br />

he saw [when he left his wood] didn’t have time<br />

to enjoy things they once had; they didn’t have<br />

enough time for the family. They would get on<br />

the train to London, get a paper, go to the office,<br />

leave the office, get another paper, and get on the<br />

train again. The only time they’re with their family<br />

was when they’re asleep, and it’s very sad.”<br />

The Pages might have had more time together<br />

than most families, but it wasn’t all harmonious.<br />

The domineering character of the father comes<br />

through more and more as the film progresses.<br />

Despite the bickering he captures, Trevelyan<br />

wasn’t aiming to portray a negative image of the<br />

family. “I was looking for the riches within the<br />

characters,” says Trevelyan. “For that reason I<br />

didn’t try to make a fly-on-the-wall documentary.<br />

I wanted the people I was filming to put forward<br />

what they had to offer.”<br />

What they do have to offer is a lot of home-spun<br />

philosophy which makes you realise how far we<br />

have moved on from the world they are so comfortable<br />

in, which predates the oil age, let alone<br />

the computer age. And what makes for uncomfortable<br />

viewing is that even though you know<br />

that their way of life is doomed, you can see that<br />

in many ways it all makes sense. And that the<br />

family are masters of their own universe, however<br />

eccentric that universe might be.<br />

It’s a beautifully made film, with no narration or<br />

extraneous explanation to distract you from the<br />

strange world that you become immersed in from<br />

the moment you meet Oily Page, playing up to<br />

the camera, reciting an old cockney rhyme, with a<br />

shotgun in one hand, a rabbit in the other.<br />

Alex Leith<br />

<strong>Brighton</strong> Festival, Duke of York’s Picturehouse,<br />

Sun 29th <strong>May</strong>, 4.30pm, followed by a Q&A with<br />

Philip Trevelyan<br />

....73....