F I - Google Docs

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

1<br />

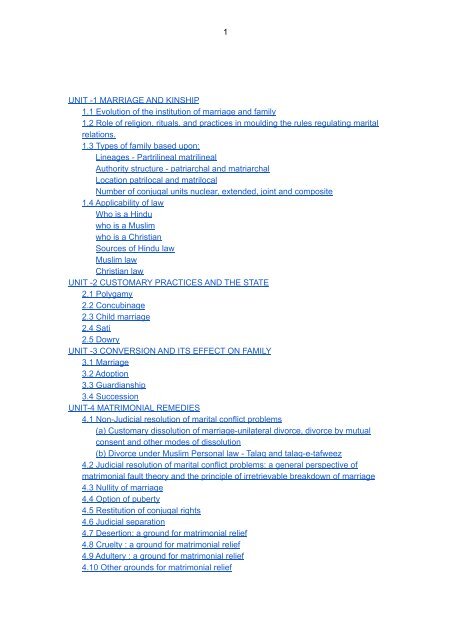

UNIT 1 MARRIAGE AND KINSHIP<br />

1.1 Evolution of the institution of marriage and family<br />

1.2 Role of religion, rituals, and practices in moulding the rules regulating marital<br />

relations.<br />

1.3 Types of family based upon:<br />

Lineages Partrilineal matrilineal<br />

Authority structure patriarchal and matriarchal<br />

Location patrilocal and matrilocal<br />

Number of conjugal units nuclear, extended, joint and composite<br />

1.4 Applicability of law<br />

Who is a Hindu<br />

who is a Muslim<br />

who is a Christian<br />

Sources of Hindu law<br />

Muslim law<br />

Christian law<br />

UNIT 2 CUSTOMARY PRACTICES AND THE STATE<br />

2.1 Polygamy<br />

2.2 Concubinage<br />

2.3 Child marriage<br />

2.4 Sati<br />

2.5 Dowry<br />

UNIT 3 CONVERSION AND ITS EFFECT ON FAMILY<br />

3.1 Marriage<br />

3.2 Adoption<br />

3.3 Guardianship<br />

3.4 Succession<br />

UNIT4 MATRIMONIAL REMEDIES<br />

4.1 NonJudicial resolution of marital conflict problems<br />

(a) Customary dissolution of marriageunilateral divorce, divorce by mutual<br />

consent and other modes of dissolution<br />

(b) Divorce under Muslim Personal law Talaq and talaqetafweez<br />

4.2 Judicial resolution of marital conflict problems: a general perspective of<br />

matrimonial fault theory and the principle of irretrievable breakdown of marriage<br />

4.3 Nullity of marriage<br />

4.4 Option of puberty<br />

4.5 Restitution of conjugal rights<br />

4.6 Judicial separation<br />

4.7 Desertion: a ground for matrimonial relief<br />

4.8 Cruelty : a ground for matrimonial relief<br />

4.9 Adultery : a ground for matrimonial relief<br />

4.10 Other grounds for matrimonial relief

2<br />

4.11 Divorce by mutual consent under Special Marriage Act, 1954<br />

4.12 Bars to matrimonial relief<br />

4.12.1 Doctrine of strict proof<br />

4.12.2 Taking advantage of one's own wrong or disability<br />

4.12.3 Accessory<br />

4.12.4 Connivance<br />

4.12.5 Collusion<br />

4.12.6 Condonation<br />

4.12.7 Improper or unnecessary delay<br />

4.12.8 Residuary clause no other legal ground exist for refusing the matrimonial<br />

relief<br />

UNIT6 CHILD AND THE FAMILY<br />

6.1 Legitimacy<br />

6.2 Adoption<br />

6.3 Custody, maintenance<br />

6.4 Guardianship<br />

UNIT7 FAMILY AND ITS CHANGING PATTERN<br />

7.1 New emerging trends<br />

7.1.1 Attenuation of family ties<br />

7.3 Process of social change in India<br />

Sanskritization<br />

Westernization<br />

Secularization<br />

Universalization and Parochialization<br />

Modernization<br />

Industrialisation<br />

Urbanization<br />

UNIT 8 ESTABLISHMENT OF FAMILY COURTS<br />

UNIT9 SECURING OF A UNIFORM CIVIL CODE<br />

9.1 Religious pluralism and its implications<br />

9.2 connotations of the directive contained in Article 44 of the constitution<br />

9.3 impediments to the formulation of the Uniform Civil Code

3<br />

UNIT 1 MARRIAGE AND KINSHIP<br />

1.1 Evolution of the institution of marriage and family<br />

Transformations in Families and Marriages Families were gradually reshaped by the<br />

discovery of agriculture; for example, the right to own land and pass it on to heirs meant that<br />

women’s childbearing abilities and male domination became more important. Rather than<br />

kinship, marriage became the center of family life and was increasingly based on a formal<br />

contractual relationship between men, women, and their kinship groups. The property and<br />

gender implications of marriage are evident in the exchange of gifts between spouses and<br />

families and clearly defined rules about the rights and responsibilities of each marital partner.<br />

During the Middle Ages, economic factors influenced marital choices more than affection,<br />

even among the poor, and women’s sexuality was treated as a form of property (Coltrane<br />

and Adams 2008:54). Wealth and power inequalities meant that marriages among the elite<br />

and/or governing classes were based largely on creating political alliances and producing<br />

male children (Coontz 2005). Ensuring paternity became important in the transfer of property<br />

to legitimate heirs, and the rights and sexuality of women were circumscribed. Ideologies of<br />

male domination prevailed, and women, especially those who were married to powerful men,<br />

were typically treated like chattel and given very few rights. The propertylike status of<br />

women was evident in Western societies like Rome and Greece, where wives were taken<br />

solely for the purpose of bearing legitimate children and, in most cases, were treated like<br />

dependents and 8——Families: A Social Class Perspective confined to activities such as<br />

caring for children, cooking, and keeping house (Ingoldsby 2006). The marriage trends of the<br />

elites were often embraced, at least ideologically, by the other social classes, even when<br />

they lacked the resources to conform to such ideologies. The focus on legalizing marriage<br />

and male domination became common among all classes, although among the less affluent<br />

there was less property to transfer to legitimate heirs, and patriarchy was mediated by the<br />

contributions of women to the family income.<br />

1.2 Role of religion, rituals, and practices in moulding the rules<br />

regulating marital relations.<br />

The growing emphasis on formal marriage contracts and patriarchy was reinforced in<br />

Western societies by the influence of Christianity and the law. Christianity was initially seen<br />

as a sect of Judaism, but with the conversion of Emperor Constantine in AD 313, it became<br />

the established religion and rose to dominate European social life for centuries (Goldthorpe<br />

1987). Christianity may have helped foster monogamy, but it distinguished itself from its<br />

forebearer, Judaism, by breaking away from Jewish traditions— which had celebrated<br />

married life, marital sexuality, and especially procreation—and providing a more circumspect<br />

view of marriage. The exposure of early Christians to the overt sexuality and eroticism that<br />

was common in Rome (Coltrane and Adams 2008:49), along with the Apostle Paul’s<br />

denunciation of marriage and the belief that the return of Jesus was imminent, led church

4<br />

leaders to eschew marriage and teach that celibacy was a higher, more exalted way of life.<br />

For many, there was an inherent conflict between pursuing the spirit and satisfying the flesh,<br />

and marriage led to the latter. Marriage was allowed, but commonly seen as a union created<br />

as the result of original sin. Thus, in most cases, marriage ceremonies had to be held<br />

outside the church doors, and a sense of impurity surrounded even marital sex and<br />

childbearing (Coltrane and Adams 2008). The marginalization of family life and marriage by<br />

early Christianity reinforced traditions that were unique to Western Europe and enhanced the<br />

wealth of the Church. Goldthorpe (1987) points out that bilateral kinship, consensual<br />

marriages, singleness as a viable option, and the nuclear family structure were common in<br />

Western Europe even before the influence of Christianity. But this restricted sense of kinship<br />

helped the Church become immensely wealthy, as its teachings discouraged marriage,<br />

stated that Christians should put the needs of the Church before family loyalties, and<br />

encouraged them to leave their property to the Church rather than to relatives (pp. 12–13).<br />

Around AD 1200, however, there was a reversal of this doctrine. Both Christian leaders and<br />

the state began to assume a larger role in defining and governing marriages, and within a<br />

century they had declared marriage a sacrament of the Christian Church and an indissoluble<br />

union (Yalom 2001; Thornton et al. 2007). Not all Christians accepted the notion of marriage<br />

as a sacrament, which essentially placed entering and dissolving marital unions under the<br />

control of the Church. Protestantism especially rejected this teaching, and the numerous<br />

sects it fostered drew on the Bible to justify a variety of marriage practices, including<br />

polygamy. Over time, however, mainstream Christian teachings supporting monogamy, non<br />

marital chastity, and marital fidelity were seen as strengthening the nuclear family, although<br />

they did little to elevate the position of women (Ingoldsby 2006). As the state and Church<br />

initiated efforts to regulate marriage, it became the core of the family; however, the debate<br />

over how one entered a legal marriage continued in most Western nations through the early<br />

1900s. People often rejected the idea of religious and state control over marriage or, more<br />

practically, simply ignored such rules about licenses and ceremonies because they lived in<br />

remote areas that made it difficult for them to avail themselves of bureaucratic procedures.<br />

The long tradition of informal marriages— described as “selfmarriages” or “living<br />

tally”—continued, and it was common for poor people to live as married without benefit of<br />

legal ceremony (Cherlin 2009). As Nancy Cott (2000:28) explains, the federal government<br />

had few ways to enforce its views on marriage, and state laws varied, often only specifying<br />

that marriages could not be bigamous, incestuous, or easily terminated. Thus, although<br />

states and religious authorities had been given the authority to perform marriage<br />

ceremonies, there was ambiguity over exactly what constituted a legal marriage. The most<br />

common bases for declaring marriages valid were mutual consent, cohabitation, and sexual<br />

consummation of the relationship, although not all of these criteria had to be met for a legally<br />

recognized marriage to exist (Thornton et al. 2007:60).<br />

1.3 Types of family based upon:<br />

Lineages Partrilineal matrilineal<br />

Patrilineality, also known as the male line, the spear side, or agnatic kinship, is a common<br />

kinship system in which an individual's family membership derives from and is traced

5<br />

through his or her father's lineage. It generally involves the inheritance of property, rights,<br />

names, or titles by persons related through male kin.<br />

The fact that human Ychromosome DNA (YDNA) is paternally inherited enables patrilines,<br />

and agnatic kinships, of men to be traced through genetic analysis.<br />

Ychromosomal Adam (YMRCA) is the patrilineal most recent common ancestor from whom<br />

all YDNA in living men is descended. An identification of a very rare and previously<br />

unknown Ychromosome variant in 2012 led researchers to estimate that Ychromosomal<br />

Adam lived 338,000 years ago, judging from molecular clock and genetic marker studies.<br />

Before this discovery, estimates of the date when Ychromosomal Adam lived were much<br />

more recent, estimated to be tens of thousands of years.<br />

Matrilineality is the tracing of descent through the female line. It may also correlate with a<br />

societal system in which each person is identified with their matriline – their mother's lineage<br />

– and which can involve the inheritance of property and/or titles. A matriline is a line of<br />

descent from a female ancestor to a descendant (of either sex) in which the individuals in all<br />

intervening generations are mothers – in other words, a "mother line". In a matrilineal<br />

descent system, an individual is considered to belong to the same descent group as her or<br />

his mother. This matrilineal descent pattern is in contrast to the more common pattern of<br />

patrilineal descent from which a family name is usually derived.<br />

Authority structure patriarchal and matriarchal<br />

Patriarchy is a social system in which males hold primary power , predominate in roles of political<br />

leadership, moral authority , social privilege and control of property. In the domain of the family,<br />

fathers or fatherfigures hold authority over women and children. Some patriarchal societies are<br />

also patrilineal , meaning that property and title are inherited by the male lineage and descent is<br />

reckoned exclusively through the male line, sometimes to the point where significantly more<br />

distant male relatives take precedence over female relatives.<br />

Matriarchy is a social system in which females hold primary power, predominate in roles of<br />

political leadership, moral authority, social privilege and control of property at the specific<br />

exclusion of men, at least to a large degree.<br />

Location patrilocal and matrilocal<br />

In social anthropology, patrilocal residence or patrilocality, also known as virilocal residence<br />

or virilocality, are terms referring to the social system in which a married couple resides with<br />

or near the husband's parents. The concept of location may extend to a larger area such as<br />

a village, town or clan territory. The practice has been found in around 70 percent of the<br />

world's cultures.

6<br />

In social anthropology, matrilocal residence or matrilocality (also uxorilocal residence or<br />

uxorilocality) is a term referring to the societal system in which a married couple resides with<br />

or near the wife's parents. Thus, the female offspring of a mother remain living in (or near)<br />

the mother's house, thereby forming large clanfamilies, typically consisting of three or four<br />

generations living in the same place.<br />

Number of conjugal units nuclear, extended, joint and composite<br />

A nuclear family or elementary family is a family group consisting of a pair of adults and their<br />

children.This is in contrast to a singleparent family, to the larger extended family, and to a<br />

family with more than two parents. Nuclear families typically centre on a married couple; the<br />

nuclear family may have any number of children.<br />

An extended family is a family that extends beyond the nuclear family, consisting of aunts,<br />

uncles, and cousins all living nearby or in the same household. An example is a married<br />

couple that lives with either the husband or the wife's parents. The family changes from<br />

immediate household to extended household. [1] In some circumstances, the extended<br />

family comes to live either with or in place of a member of the immediate family. These<br />

families include, in one household, near relatives in addition to an immediate family. An<br />

example would be an elderly parent who moves in with his or her children due to old age.<br />

Historically, for generations India had a prevailing tradition of the joint family system or<br />

undivided family. The system is an extended family arrangement prevalent throughout the<br />

Indian subcontinent, particularly in India, consisting of many generations living in the same<br />

home, all bound by the common relationship. A patrilineal joint family consists of an older<br />

man and his wife, his sons and daughters and his grandchildren from his sons and<br />

daughters.<br />

1.4 Applicability of law<br />

Who is a Hindu<br />

The term Hindu is derived from Greek word Indoi. Greeks used to call inhabitants of the<br />

indus valley as Indoi. The law which governs Hindus is called Hindu Law.<br />

Hindus may be subdivided into following Categories<br />

1. Hindu by Birth One or Both Parents are Hindus at the time of the Birth<br />

2. Hindu by Religion Hindus, Jains, Sikhs, Buddhists by Religion<br />

3. Hindu by Conversion Converts or Reconverts to Hindu, Jain, Buddhist

7<br />

who is a Muslim<br />

Muslim is a person who believes that Allah is the only God and Mohammed Prophet is his<br />

messenger. Also he believes that Quran is the compilations of words directly revealed by<br />

God to Mohammed Prophet.<br />

Muslims may be subdivided into following Categories<br />

1. Muslim by Birth Both the parents are Muslims and he is brought up as Muslim<br />

2. Muslim by Religion Sunnis and Shias<br />

3. Muslim by Conversion One who converts as Muslim by accepting Allah, Quran and<br />

Prophet. He can go to Majid and can sign register with Imam to become a Muslim.<br />

who is a Christian<br />

<br />

Sources of Hindu law<br />

1. Ancient Sources<br />

a. Sruti Vedas<br />

b. Smriti Manu smriti<br />

c. Commentaries and Digests Manu Bhashyam<br />

d. Custom Achara or Usage Achara Paramodharmaha<br />

i. Local Custom<br />

ii. Family Custom<br />

iii. Caste Custom<br />

2. Modern Sources<br />

a. Equity, Justice and good conscience<br />

b. Precedent<br />

c. Legislation<br />

Muslim law<br />

<br />

Christian law

8<br />

UNIT 2 CUSTOMARY PRACTICES AND THE<br />

STATE<br />

2.1 Polygamy<br />

Polygamy (from Late Greek polygamia, "state of marriage to many spouses") involves<br />

marriage with more than one spouse. When a man is married to more than one wife at a<br />

time, it is called polygyny. When a woman is married to more than one husband at a time, it<br />

is called polyandry.<br />

Thus Polygamy became illegal in India in 1956, uniformly for all of its citizens except for<br />

Hindus in Goa where bigamy is legal, and for Muslims, who are permitted to have four wives.<br />

In a polygamous Hindu marriage is null and void.<br />

(1) The offence known as ‘bigamy’ is committed when a person having a husband or wife<br />

living, (2) marries in any case in which marriage is void, (3) by reason of it taking place<br />

during the life of such husband or wife. Such person is punishable with imprisonment of<br />

either description upto seven years and fine. (Section 494)<br />

2.2 Concubinage<br />

Concubinage is an interpersonal relationship in which a person engages in an ongoing<br />

sexual relationship with another person to whom they are not or cannot be married to the full<br />

extent of the local meaning of marriage. The inability to marry may be due to multiple factors<br />

such as differences in social rank status, an existent marriage, religious prohibitions,<br />

professional ones (for example Roman soldiers) or a lack of recognition by appropriate<br />

authorities. The woman in such a relationship is referred to as a concubine.<br />

The prevalence of concubinage and the status of rights and expectations of a concubine<br />

have varied between cultures as well as the rights of children of a concubine. Whatever the<br />

status and rights of the concubine, they were always inferior to those of the wife, and<br />

typically neither she nor her children had rights of inheritance. Historically, concubinage was<br />

frequently entered into voluntarily (by the woman or her family) as it provided a measure of<br />

economic security for the woman involved. Involuntary or servile concubinage sometimes<br />

involved sexual slavery of one member of the relationship, usually the woman.<br />

Keeping a concubine is a good ground for divorce. Under the ancient hindu law, a hindu can<br />

keep as many wives as his physical and monetary capacity permitted him to do so. This<br />

defect of ancient hindu law is removed and now husband can marry only one wife and<br />

cannot keep concubine.<br />

On the other hand, Muslim law is very strict about Concubinage. It permits a man to keep 4<br />

wives but not a concubine. It is specifically provided in the Islamic law that a concubine

9<br />

doesn’t have any right of inheritance nor the children of concubine will have any right of<br />

inheritance. They will be treated as Bastards.<br />

2.3 Child marriage<br />

Child marriage in India, according to the Indian law, is a marriage where either the woman is<br />

below age 18 or the man is below age 21. Most child marriages involve underage women,<br />

many of whom are in poor socioeconomic conditions.<br />

The Child Marriage Restraint Act of 1929<br />

The Child Marriage Restraint Act, also called the Sarda Act, was a law to restrict the practice<br />

of child marriage. It was enacted on 1 April 1930, extended across the whole nation, with the<br />

exceptions of the states of Jammu and Kashmir, and applied to every Indian citizen. Its goal<br />

was to eliminate the dangers placed on young girls who could not handle the stress of<br />

married life and avoid early deaths. This Act defined a male child as 21 years or younger, a<br />

female child as 18 years or younger, and a minor as a child of either sex 18 years or<br />

younger. The punishment for a male between 18 and 21 years marrying a child became<br />

imprisonment of up to 15 days, a fine of 1,000 rupees, or both. The punishment for a male<br />

above 21 years of age became imprisonment of up to three months and a possible fine. The<br />

punishment for anyone who performed or directed a child marriage ceremony became<br />

imprisonment of up to three months and a possible fine, unless he could prove the marriage<br />

he performed was not a child marriage. The punishment for a parent or guardian of a child<br />

taking place in the marriage became imprisonment of up to three months or a possible fine.<br />

It was amended in 1940 and 1978 to continue raising the ages of male and female children.<br />

The Prohibition of Child Marriage Act, 2006<br />

In response to the plea (Writ Petition (C) 212/2003) of the Forum for Factfinding<br />

Documentation and Advocacy at the Supreme Court, the Government of India brought the<br />

Prohibition of Child Marriage Act (PCMA) in 2006, and it came into effect on 1 November<br />

2007 to address and fix the shortcomings of the Child Marriage Restraint Act. The change in<br />

name was meant to reflect the prevention and prohibition of child marriage, rather than<br />

restraining it. The previous Act also made it difficult and time consuming to act against child<br />

marriages and did not focus on authorities as possible figures for preventing the marriages.<br />

This Act kept the ages of adult males and females the same but made some significant<br />

changes to further protect the children. Boys and girls forced into child marriages as minors<br />

have the option of voiding their marriage up to two years after reaching adulthood, and in<br />

certain circumstances, marriages of minors can be null and void before they reach<br />

adulthood. All valuables, money, and gifts must be returned if the marriage is nullified, and<br />

the girl must be provided with a place of residency until she marries or becomes an adult.<br />

Children born from child marriages are considered legitimate, and the courts are expected to<br />

give parental custody with the children's best interests in mind. Any male over 18 years of<br />

age who enters into a marriage with a minor or anyone who directs or conducts a child<br />

marriage ceremony can be punished with up to two years of imprisonment or a fine.

10<br />

2.4 Sati<br />

Sati is an obsolete Hindu funeral custom where a widow immolated herself on her<br />

husband's pyre, or committed suicide in another fashion shortly after her husband's death.<br />

Mention of the practice can be dated back to the 4th century BC,while evidence of practice<br />

by wives of dead kings only appears beginning between the 5th and 9th centuries AD. The<br />

practice is considered to have originated within the warrior aristocracy on the Indian<br />

subcontinent, gradually gaining in popularity and spreading to other groups. The practice<br />

was particularly prevalent among some Hindu communities.<br />

THE COMMISSION OF SATI (PREVENTION) ACT<br />

Sati (Prevention) Act, 1987 is law enacted by Government of Rajasthan in 1987. It became<br />

an Act of the Parliament of India with the enactment of The Commission of Sati (Prevention)<br />

Act, 1987 in 1988. The Act seeks to prevent Sati practice or the voluntary or forced burning<br />

or burying alive of widows, and to prohibit glorification of this action through the observance<br />

of any ceremony, the participation in any procession, the creation of a financial trust, the<br />

construction of a temple, or any actions to commemorate or honor the memory of a widow<br />

who committed sati.<br />

2.5 Dowry<br />

The Dowry system refers to the durable goods, cash, and real or movable property that the<br />

bride's family gives to the bridegroom, his parents, or his relatives as a condition of the<br />

marriage. It is essentially in the nature of a payment in cash or some kind of gifts given to the<br />

bridegroom's family along with the bride and includes cash, jewellery, electrical appliances,<br />

furniture, bedding, crockery, utensils and other household items that help the newlyweds set<br />

up their home.<br />

The dowry system is thought to put great financial burden on the bride's family. In some<br />

cases, the dowry system leads to crime against women, ranging from emotional abuse,<br />

injury to even deaths. The payment of dowry has long been prohibited under specific Indian<br />

laws including, the Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961 and subsequently by Sections 304B and<br />

498A of the Indian Penal Code.<br />

Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961<br />

The Dowry Prohibition Act, 1961 consolidated the antidowry laws which had been passed<br />

on certain states. This legislation provides for a penalty in section 3 if any person gives,<br />

takes or abets giving or receiving of dowry. The punishment could be imprisonment for a<br />

term not less than 5 years and a fine not less than ₹15,000 or the value of the dowry<br />

received, whichever is higher. Dowry in the Act is defined as any property or valuable<br />

security given or agreed to be given in connection with the marriage. The penalty for giving<br />

or taking dowry is not applicable in case of presents which are given at the time of marriage<br />

without any demand having been made.

11<br />

UNIT 3 CONVERSION AND ITS EFFECT ON<br />

FAMILY<br />

The effects of conversion from one religion to another under Hindu Law are described<br />

below:(A) Law Applicable: The effect of conversion from one religion to another on the law<br />

applicable to the convert was considered by the Privy Council in Abraham v. Abraham,<br />

1863 (9) MIA 195. M.Abraham’s ancestors were Hindus who were converted into<br />

Christianity. On the death of M. Abraham his widow brought the suit for recovery of his<br />

property. This suit was resisted by his brother F. Abraham who contended that his ancestors<br />

continued to be governed by the Hindu Law in spite of conversion. He accordingly claimed<br />

that he was entitled to the entire property according to the Hindu Law of survivorship<br />

applicable to a joint Hindu family. The Privy Council held: — (1) The effect of conversion of a<br />

Hindu to Christianity is to sever his connection with the Hindu family. (2) Such a person may<br />

renounce the Hindu Law but is not bound to do so. He may elect “to abide by the old law,<br />

notwithstanding that he has renounced the old religion” (3) The course of conduct of the<br />

convert after his conversion would show by what law he had elected to be governed. Under<br />

the third principle it was found that M. Abraham had married a Christian woman who was<br />

born to an English father and a Portuguese mother, that he adopted English dress and<br />

manner. It was clear, therefore, that he had elected against the Hindu Law and so the<br />

defendant’s contention based upon the Hindu Law of survivorship was rejected. In 1865 the<br />

Indian Succession Act was passed and it regulated succession to the property of Christian.<br />

The question arose whether even after the passing of this Act; it was open to a Christian<br />

convert from Hinduism to elect to be governed by the Hindu Law of Succession. It was held<br />

by the Privy Council in Kamuwati v. Digbijai Singh, 43 All. 525 (PC), that after the coming<br />

into force of the Act of 1865 the rule in Abraham’s case ceased to be applicable so far as law<br />

of the inheritance is concerned. The plaintiff in that case who was the sister of the deceased<br />

owner, who was a Christian convert from Hinduism, was held to be entitled to succeed to<br />

1/12th of his property under the Act of 1865 and the defendant’s (brother’s) claim based<br />

upon Hindu Law to succeed to the entire property was rejected. But in spite of the Act of<br />

1865, a Hindu convert to Christianity could elect to be governed by the rule of survivorship in<br />

a joint family: Francis Ghosal v. Grabri Ghosal, 31 Bom. 251 (PC).So the rule of electing to<br />

be governed by Hindu Law was applicable to a limited extent to Christian converts even after<br />

1865. In the case of conversion to Mohammedanism also the old rule was that by custom<br />

the convert had an option to be governed by the old Hindu Law. Thus Khojas and Cutchi<br />

Memons of Bombay State were governed in matters of succession by Hindu Law though<br />

they had been converted to Islam. The Shariat Act, 1937, has put an end to this. Under that<br />

Act converts to Islam are governed by Mahomedan Law only and not by the law to which<br />

they were subject prior to the conversion.

12<br />

3.1 Marriage<br />

Conversion of one of the parties to a marriage has certain effect under the law applicable<br />

prior to conversion. If a Mahomedan husband renounces Islam and embraces<br />

another religion, the marriage is immediately treated as dissolved: If a Mahomedan wife<br />

embraces another religion, the same consequence followed under the Mahomedan Law but<br />

the law has been modified by the Dissolution of Muslim Marriage Act, 1939. Under that Act<br />

the wife canon her conversion seek a divorce on any of the grounds mentioned in that Act.<br />

Under the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, conversion of either party is per se a ground for<br />

seeking divorce to the other party. Thus if the wife renounces Hinduism the husband can<br />

seek a divorce and vice versa [Sec. 13 clauses (1) subclause (ii)]. In Vilayat v. Sunila, AIR<br />

1983 Delhi 351, the question has arisen whether a Hindu husband,who has embraced Islam<br />

subsequent to the marriage, can file a petition for divorce under the Hindu Marriage Act. It<br />

was held by Leila Seth. J., that he could do so for under s. 13 “at the time of presentation of<br />

the petition, the parties need not be Hindus”. In this view the person allaw according to which<br />

the marriage took place will govern the rights of the parties as to the dissolution of the<br />

marriage. Suppose both the parties to the marriage embrace Islam. The view of Leila Seth.<br />

J., would still subject the parties to the remedies available under the Hindu Law in regard to<br />

the dissolution of the marriage. But such a view is opposed to the rule laid down in<br />

Khambatta v.Khambatta, 1934 (36) Bom. LR 1021, where in such a situation divorce by<br />

Talak under the Mahomedan Law was upheld.Thus the view of Leila Seth, cannot be<br />

pressed to its logical conclusion. It should be restricted to the facts of that case. If one of the<br />

parties to a Hindu marriage becomes a convert to another religion, he is not according to this<br />

view, disabled from filing a petition under s. 13of the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955.(D) Effect of<br />

Conversion on Right to Maintenance: Under the Hindu Law conversion from Hinduism<br />

operates as a forfeiture of the right of the convert to claim maintenance (see s. 24 the Hindu<br />

Adoptions and Maintenance Act, 1956).When the husband renounces Hinduism, his Hindu<br />

wife becomes entitled to claim a right to separate residence and maintenance from him<br />

Hindu Adoption and Maintenance Act [s. 18(2) (f)]. Conversion from Islam affects a forfeiture<br />

of the preexisting maintenance rights. When the husband renounces Islam, the marriage is<br />

at an end and so maintenance can be claimed by the wife during the period of iddat.<br />

3.2 Adoption<br />

3.3 Guardianship<br />

The paramount consideration in regard to guardianship is the welfare of the minor. So when<br />

the parent having guardianship changes his or her religion, it is a factor to be taken into<br />

account in considering the fitness of the parent to continue as guardian. This was decided by<br />

the Privy Council in Helen Kinner v. Sophia, 14 МIA 309

13<br />

3.4 Succession<br />

Under the Hindu Law a convert from Hinduism could not inherit to the Hindu<br />

relations.Similarly under the Mahomedan Law a convert from Islam to some other religion is<br />

excluded from inheritance. This rule has been abrogated by the Caste Disabilities Removal<br />

Act, XXI of 1850. This Act is also called the Freedom of Religion Act. It has abolished the<br />

customary law which entails forfeiture of rights inheritance consequent upon conversion or<br />

deprivation of caste.

14<br />

UNIT4 MATRIMONIAL REMEDIES<br />

4.1 NonJudicial resolution of marital conflict problems<br />

(a) Customary dissolution of marriageunilateral divorce, divorce by<br />

mutual consent and other modes of dissolution<br />

(1) By Mutual Consent:<br />

The custom of obtaining divorce by mutual consent is prevalent among certain castes in<br />

Bombay, Madras, Mysore and Kerala. In Madhya Pradesh it has been held that divorce by<br />

mutual consent is a valid custom among the Patwas of that State.<br />

A customary form of divorce by agreement (chuttamchutta) amongst the Barai Chaurasiyas<br />

of Uttar Pradesh has been declared valid by the Allahabad High Court. These are only a few<br />

illustrations to indicate the existence of divorce by mutual consent.<br />

(2) Unilateral Divorce:<br />

According to the custom prevailing in Manipur (Khaniaba), it has been stated that a husband<br />

can dissolve the marriage without any reason or at his pleasure.<br />

Among the Rajpur Gujaratis in Khandesh, and in the Pakhali Community marriage is<br />

dissolved if the husband abandons or deserts the wife.<br />

Among the Vaishyas of Gorakhpur in Uttar Pradesh a husband may abandon or desert his<br />

wife, and dissolution takes place even without reference to the caste tribunal.<br />

(3) Divorce by Deed:<br />

This form is prevalent among certain castes in South India, also in Himachal Pradesh and<br />

the Jat community. Recently the Supreme Court has upheld a deed executed by the<br />

husband divorcing his wife.<br />

Usually customary divorces are through the intervention of the traditional Panchayats of<br />

caste tribunals. Therefore, in States where this has not been customary, the courts have not<br />

permitted Panchayats to take upon themselves the right to dissolve a marriage. Once the<br />

custom is proved, however, the courts will not interfere.<br />

The courts have exercised a lot of judicial scrutiny and discretion in upholding or rejecting<br />

such customary divorce practices. In doing so they have applied the strict test for the validity<br />

of such customs.

15<br />

When the existence of a custom was not proved, or where the custom could be regarded as<br />

running counter to the spirit of Hindu Law, or was against public policy or morality, courts<br />

have declared such customary forms of divorce as invalid.<br />

Under customary law there is no waiting period after divorce to remarry. But if divorce is<br />

obtained under the Hindu Marriage Act, then either party to the marriage can lawfully<br />

remarry only after a lapse of one year after the decree of divorce (Sec. 15).<br />

Retention of customary forms of divorce under the Hindu Marriage Act is advantageous<br />

because this process of dissolving the marriage saves time and money in litigations. The<br />

only difficulty that may arise is if the divorce according to customary law is brought at some<br />

stage to the notice of the court and the latter decrees that particular form of divorce to be<br />

against public policy or morality. If one or both parties have remarried, such a marriage will<br />

be void and the status of the children will be affected.<br />

To minimize this, it has been suggested that the Ministry of Law should prepare an<br />

exhaustive record of customs relating to divorce found in different States and set up a panel<br />

of sociolegal experts to determine if any of these customs are invalid. Copies of the record<br />

should be made freely and easily available to the people and the Panchayats.<br />

With the enactment of the Hindu Marriage Act of 1955, divorce became a part of the law<br />

governing all Hindus. The ground for this had been already prepared by the passing of the<br />

Hindu Women’s Right to Separate Residence and Maintenance Act in 1946, which inter alia<br />

permitted the wife to separate from her husband on the ground that he had married again.<br />

Following this, some of the States took the initiative and as with monogamy, legislated to<br />

permit divorce for Hindus.<br />

(b) Divorce under Muslim Personal law Talaq and talaqetafweez<br />

Talaq In the ṭalāq divorce, the husband pronounces the phrase "I divorce you" (in Arabic,<br />

talaq) to his wife. A man may divorce his wife three times, taking her back after the first two<br />

(reconciling). After the third talaq they can't get back together until she marries someone<br />

else. Some do a "triple ṭalāq", in which the man says in one sitting "I divorce you" three times<br />

(or "I divorce you, three times", "you're triple divorced"). Many Islamic scholars believe there<br />

is a waiting period involved between the three talaqs, pointing to Quran and various hadiths.<br />

However the practice of "triple ṭalāq" at one sitting has been "legally recognized historically<br />

and has been particularly practiced in Saudi Arabia."<br />

The talaq has three steps:<br />

1. Initiation<br />

2. Reconciliation<br />

3. Completion

16<br />

Talaqetafweez<br />

Where husband delegate the power to give divorce to the wife or to a third person,either<br />

absolutely or conditionally, and either for a particular period or permanently. The delegate<br />

may then pronounce the divorce accordingly; such a divorce is known as “Talaq by Tafweez”<br />

or “ TalaqeTafweez”.<br />

Although the power to give divorce belongs to the husband, yet he may delegate the power<br />

to the wife or to a third person,either absolutely or conditionally, and either for a particular<br />

period or permanently. The person to whom the power is thus delegated may then<br />

pronounce the divorce accordingly. Such a divorce is known as “Talaq by Tafweez”. The<br />

delegation of option called “Tafweez” by the husband to his wife, confers on her the power to<br />

divorce herself. Tafweez is of three kinds:<br />

Kinds of TalaqeTafweez :<br />

Tafweez is of three kinds,<br />

(a)Ikhtiar, giving her the authority to divorce herself.<br />

(b)Amrbayed, leaving the matter in her own hand.<br />

(c)Mashiat, giving her the option to do what she likes.<br />

All these when analyzed, resolve themselves into one, viz, leaving it in her or somebody else<br />

to option to do what she or he likes.<br />

4.2 Judicial resolution of marital conflict problems: a general<br />

perspective of matrimonial fault theory and the principle of<br />

irretrievable breakdown of marriage<br />

There are basically three theories for divorcefault theory, mutual consent theory &<br />

irretrievable breakdown of marriage theory.<br />

Under the Fault theory or the offences theory or the guilt theory, marriage can be dissolved<br />

only when either party to the marriage has committed a matrimonial offence. It is necessary<br />

to have a guilty and an innocent party, and only innocent party can seek the remedy of<br />

divorce. However the most striking feature and drawback is that if both parties have been at<br />

fault, there is no remedy available.<br />

Another theory of divorce is that of mutual consent. The underlying rationale is that since two<br />

persons can marry by their free will, they should also be allowed to move out of their<br />

relationship of their own free will. However critics of this theory say that this approach will<br />

promote immorality as it will lead to hasty divorces and parties would dissolve their marriage<br />

even if there were slight incompatibility of temperament.<br />

The third theory relates to the irretrievable breakdown of marriage. The breakdown of

17<br />

marriage is defined as “such failure in the matrimonial relationships or such circumstances<br />

adverse to that relation that no reasonable probability remains for the spouses again living<br />

together as husband & wife.” Such marriage should be dissolved with maximum fairness &<br />

minimum bitterness, distress & humiliation.<br />

Some of the grounds available under Hindu Marriage Act can be said to be under the theory<br />

of frustration by reason of specified circumstances. These include civil death, renouncement<br />

of the world etc<br />

4.3 Nullity of marriage<br />

What Is Annulment of Marriage<br />

In strict Legal terminology, annulment refers only to making a voidable marriage null; if the<br />

marriage is void ab initio, then it is automatically null, although a legal declaration of nullity is<br />

required to establish this.<br />

Annulment is a legal procedure for declaring a marriage null and void. With the exception of<br />

bigamy and not meeting the minimum age requirement for marriage, it is rarely granted. A<br />

marriage can be declared null and void if certain legal requirements were not met at the time<br />

of the marriage. If these legal requirements were not met then the marriage is considered to<br />

have never existed in the eyes of the law. This process is called annulment. It is very<br />

different from divorce in that while a divorce dissolves a marriage that has existed, a<br />

marriage that is annulled never existed at all. Thus unlike divorce, it is retroactive: an<br />

annulled marriage is considered never to have existed.<br />

Grounds for Annulment<br />

The grounds for a marriage annulment may vary according to the different legal jurisdictions,<br />

but are generally limited to fraud, bigamy, blood relationship and mental incompetence<br />

including the following:<br />

1) Either spouse was already married to someone else at the time of the marriage in<br />

question;<br />

2) Either spouse was too young to be married, or too young without required court or<br />

parental consent. (In some cases, such a marriage is still valid if it continues well beyond the<br />

younger spouse's reaching marriageable age);<br />

3) Either spouse was under the influence of drugs or alcohol at the time of the marriage;<br />

4) Either spouse was mentally incompetent at the time of the marriage;<br />

5) If the consent to the marriage was based on fraud or force;<br />

6) Either spouse was physically incapable to be married (typically, chronically unable to have<br />

sexual intercourse) at the time of the marriage;<br />

7) The marriage is prohibited by law due to the relationship between the parties. This is the<br />

"prohibited degree of consanguinity", or blood relationship between the parties. The most<br />

common legal relationship is 2nd cousins; the legality of such relationship between 1st<br />

cousins varies around the world.<br />

8) Prisoners sentenced to a term of life imprisonment may not marry.<br />

9) Concealment (e.g. one of the parties concealed a drug addiction, prior criminal record or<br />

having a sexually transmitted disease).

18<br />

Basis of an Annulment<br />

In Section 5 of the Hindu Marriage Act 1955, there are some conditions laid down for a<br />

Hindu Marriage which must be fulfilled in case of any marriage between two Hindus which<br />

can be solemnized in accordance with the requirements of this Act.<br />

Section 5 Condition for a Hindu Marriage A marriage may be solemnized between any two<br />

Hindus, if the following conditions are fulfilled, namely:<br />

(i) Neither party has a spouse living at the time of the marriage;<br />

(ii) At the time of the marriage, neither party,<br />

(a) is incapable of giving a valid consent of it in consequence of unsoundness of mind; or<br />

(b) though capable of giving a valid consent has been suffering from mental disorder of such<br />

a kind or to such an extent as to be unfit for marriage and the procreation of children; or<br />

(c) has been subject to recurrent attacks of insanity or epilepsy;<br />

(iii) The bridegroom has completed the age of twenty one years and the bride the age of<br />

eighteen years at the time of the marriage;<br />

(iv) The parties are not within the degrees of prohibited relationship unless the custom or<br />

usage governing each of them permits of a marriage between the two;<br />

(v) The parties are not sapindas of each other, unless the custom or usage governing each<br />

of them permits of a marriage between the two:<br />

An annulment may be granted when a marriage is automatically void under the law for public<br />

policy reasons or voidable by one party when certain requisite elements of the marriage<br />

contract were not present at the time of the marriage.<br />

Void Marriages<br />

A marriage is automatically void and is automatically annulled when it is prohibited by law.<br />

Section 11 of Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 deals with:<br />

Nullity of marriage and divorce Void marriages Any marriage solemnized after the<br />

commencement of this Act shall be null and void and may, on a petition presented by either<br />

party thereto, against the other party be so declared by a decree of nullity if it contravenes<br />

any one of the conditions specified in clauses (i), (iv) and (v), Section 5 mentioned above.<br />

Bigamy If either spouse was still legally married to another person at the time of the<br />

marriage then the marriage is void and no formal annulment is necessary.<br />

Interfamily Marriage. A marriage between an ancestor and a descendant, or between a<br />

brother and a sister, whether the relationship is by the half or the whole blood or by adoption.<br />

Marriage between Close Relatives. A marriage between an uncle and a niece, between an<br />

aunt and a nephew, or between first cousins, whether the relationship is by the half or the<br />

whole blood, except as to marriages permitted by the established customs.<br />

Voidable Marriages<br />

A voidable marriage is one where an annulment is not automatic and must be sought by one

19<br />

of the parties. Generally, an annulment may be sought by one of the parties to a marriage if<br />

the intent to enter into the civil contract of marriage was not present at the time of the<br />

marriage, either due to mental illness, intoxication, duress or fraud.<br />

4.4 Option of puberty<br />

When a minor’s marriage is contracted by any guardian other than the father or father’s<br />

father, the minor has the option to repudiate the marriage on attaining puberty . This option<br />

is legally called as khyarulbulugh or ’option of puberty’ . The right to exercise the option<br />

of puberty is different , in different circumstances , in the case of Mahomedan male and<br />

female .<br />

a) In the case of a female, if after attaining puberty and after being informed of the<br />

marriage and her right to repudiate it, she does not repudiate without unreasonable delay ,<br />

the right of repudiating the marriage is lost,. But according to the Dissolution of Muslim<br />

Marriages Act, 1939, if the marriage has not been consummated , she enjoys the right to<br />

repudiate the marriage before attaining the age of eighteen years .<br />

b) In the case of male, the right continues until he has ratified the marriage either expressly<br />

or impliedly as by payment of dower or by cohabitation.<br />

The Dissolution of Muslim Marriages Act, 1939, has removed all restrictions on the exercise<br />

of option of puberty in the case of a minor girl whose marriage has been arranged by a<br />

father or grandfather .<br />

According to sec.2 (vii) of the Act a wife is entitled to the dissolution of her marriage if she<br />

proves the following facts …..<br />

I) that the marriage has not been consummated<br />

2) that the marriage took place before she attained the age of 15 years and<br />

3) that she has repudiated the marriage before attaining the age of 18 years .<br />

A decree of Court to invalidate the marriage is necessary.<br />

Shia law differs than that of the Sunni law in this respect . According to the Shia law, if a<br />

marriage of minor is brought about by a person other than a father or grandfather the<br />

marriage is wholly ineffective until it is ratified by the minor on attaining puberty .<br />

As regards effects of the exercise of the opinion of puberty , the mere repudiation does not<br />

operate as a dissolution of the marriage. The Court must confirm the repudiation . Uptil<br />

confirmation of the repudiation by the Court the marriage subsists . In the event of death of<br />

either party to the marriage, before confirmation of the repudiation by the Court , the other<br />

will inherit from him or from her, as the case may be.

20<br />

4.5 Restitution of conjugal rights<br />

Section 1 of the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 embodies the concept of Restitution of Conjugal<br />

Rights under which after solemnization of marriage if one of the spouses abandons the<br />

other, the aggrieved party has a legal right to file a petition in the matrimonial court for<br />

restitution of conjugal rights. This right can be granted to any of the spouse.<br />

This section is identical to section 22 of the Special Marriage Act, 1954. The provision is in<br />

slightly different wordings in the Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act, 1936, but it has been<br />

interpreted in such a manner that it has been given the same meaning as under the Hindu<br />

Marriage Act, 1955 and the Special Marriage Act, 1954. However, the provision is different<br />

under the section 32 Indian Divorce Act, 1869 but efforts are being made to give it such an<br />

interpretation so as to bring it in consonance with the other laws. The provision under Muslim<br />

law is almost the same as under the modern Hindu law, though under Muslim law and under<br />

the Parsi Marriage and Divorce Act, 1936 a suit in a civil court has to be filed and not a<br />

petition as under other laws.<br />

The constitutional validity of the provision has time and again been questioned and<br />

challenged. The earliest being in 1983 before the Andhra Pradesh High Court[4] where the<br />

Hon'ble High Court held that the impugned section was unconstitutional. The Delhi High<br />

Court in Harvinder Kaur v Harminder Singh, though had nonconforming views. Ultimately<br />

Supreme Court in Saroj Rani v. Sudharshan, gave a judgment which was in line with the<br />

Delhi High Court views and upheld the constitutional validity of the section 9 and overruled<br />

the decision given in<br />

4.6 Judicial separation<br />

Judicial separation is an instrument devised under law to afford some time for introspection<br />

to both the parties to a troubled marriage. Law allows an opportunity to both the husband<br />

and the wife to think about the continuance of their relationship while at the same time<br />

directing them to live separate, thus allowing them the much needed space and<br />

independence to choose their path.<br />

Judicial Separation and Divorce in India as per Hindu Marriage Act<br />

Judicial separation is a sort of a last resort before the actual legal break up of marriage i.e.<br />

divorce. The reason for the presence of such a provision under Hindu Marriage Act is the<br />

anxiety of the legislature that the tensions and wear and tear of every day life and the strain<br />

of living together do not result in abrupt break – up of a marital relationship. There is no<br />

effect of a decree for judicial separation on the subsistence and continuance of the legal<br />

relationship of marriage as such between the parties. The effect however is on their<br />

cohabitation. Once a decree for judicial separation is passed, a husband or a wife,<br />

whosoever has approached the court, is under no obligation to live with his / her spouse .<br />

The provision for judicial separation is contained in section 10 of the Hindu Marriage Act,

21<br />

1955. The section reads as under:<br />

A decree for judicial separation can be sought on all those ground on which decree for<br />

dissolution of marriage, i.e. divorce can be sought.<br />

Hence, judicial separation can be had on any of the following grounds:<br />

1. Adultery<br />

2. Cruelty<br />

3. Desertion<br />

4. Apostacy (Conversion of religion)<br />

5. Insanity<br />

6. Virulent and incurable form of leprosy<br />

7. Venereal disease in a communicable form<br />

8. Renunciation of world by entering any religious order<br />

9. Has not been heard of as being alive for seven years<br />

If the person applying for judicial separation is the wife, then the following grounds are also<br />

available to her:<br />

Remarriage or earlier marriage of the husband but solemnised before the commencement of<br />

Hindu Marriage Act, 1955, provided the other wife is alive at the time of presentation of<br />

petition for judicial separation by the petitioner wife.<br />

Rape, sodomy or bestiality by the husband committed after the solemnization of his marriage<br />

with the petitioner.<br />

Nonresumption of cohabitation between the parties till at least one year after an award of<br />

maintenance was made by any court against the husband and in favour of the petitioner<br />

wife.<br />

Solemnization of the petitioner wife’s marriage with the respondent husband before she had<br />

attained the age of 15 years provided she had repudiated the marriage on attaining the age<br />

of 15 years but before attaining the age of 18 years.<br />

It is on all the above grounds that judicial separation can be sought. The first 9 grounds are<br />

available to both the husband and the wife but the last four grounds are available only to the<br />

wife. It is to be noted that it is on these grounds that divorce is also to be granted. It has<br />

been held that unless a case for divorce is made out, the question of granting judicial<br />

separation does not arise. Therefore, the Courts while dealing with the applications for<br />

judicial separation shall bear in mind the specific grounds raised for grant of relief claimed<br />

and insist on strict proof to establish those grounds and shall not grant some relief or the<br />

other as a matter of course. Thus on a petition for divorce, the Court has discretion in<br />

respect of the grounds for divorce other than those mentioned in section 13 (1A) and also<br />

some other grounds to grant restricted relief of judicial separation instead of divorce<br />

straightway<br />

if it is just having regard to the facts and circumstances.

22<br />

Another question that arises is of decree of maintenance visàvis decree for judicial<br />

separation. Where a decree for judicial separation was obtained by the husband against her<br />

wife who had deserted him, the wife not being of unchaste character nor her conduct being<br />

flagrantly vicious, the order of alimony made in favour of the wife was not interfered with by<br />

the Court.<br />

4.7 Desertion: a ground for matrimonial relief<br />

In explanation to subsection (1) of Section 13, Hindu Marriage Act, Parliament has thus<br />

explained desertion: “The expression ‘desertion’ means the desertion of the petitioner by the<br />

other party to the marriage without reasonable cause and without the consent or against the<br />

wish of such party, and includes the willful neglect of the petitioner by the other party to<br />

marriage, and its grammatical variations and cognate expressions shall be construed<br />

accordingly.” [4] In its essence desertion means the intentional permanent forsaking and<br />

abandonment of one spouse by the other without that other’s consent and reasonable<br />

cause. It is a total repudiation on the obligations of the marriage.[5]<br />

For the offence of desertion, so far as the deserting spouse is concerned, two essential<br />

conditions are required: (1) the factum of separation, and (2) the intention to bring<br />

cohabitation permanently to an end (animus deserendi). In actual desertion, it is necessary<br />

that respondent must have forsaken or abandoned the matrimonial home. Suppose, a<br />

spouse every day, while he goes to bed resolves to abandon the matrimonial home the next<br />

day but continues to stay there, he had formed the intention but that intention has not been<br />

translated to action. He cannot be said to have deserted the other spouse.[6] On the other<br />

hand, if a spouse leaves the matrimonial home for studies or business and goes to another<br />

place for some period, with the clear intention that, after completion of studies or work he<br />

would return home but is not able to return because of illness or other work. In this case the<br />

factum of separation is there but, but his intention to desert is lacking, therefore this will not<br />

constitute desertion.<br />

Similarly, two elements are essential so far as the deserted spouse in concerned: (1) the<br />

absence of the consent, and (2) absence of conduct giving reasonable cause to the spouse<br />

leaving the matrimonial home to form the necessary intention . If one party leaves the<br />

matrimonial home with the consent of the other party, he or she is not guilty of desertion. For<br />

instance, if husband leaves his wife to her parent’s house, it is not desertion as husband’s<br />

consent is present. Again, a pregnant wife who goes to her father’s place for delivery without<br />

the consent of the husband cannot be treated in desertion.[7] Desertion is a matter of<br />

inference to be drawn from the facts and circumstances of each case.[8] The offence of<br />

desertion commences when the fact of separation and the animus deserendi coexist. But it<br />

is not necessary that both should commence at the same time. The de facto separation may<br />

have commenced without the necessary animus or it may be that the separation and the<br />

animus deserendi coincide in point of time.. However it is not necessary that the intention<br />

must precede the factum. For instance, a husband goes abroad for studies, initially he is<br />

contact with wife but slowly he ceases that contact. He develops attachment with another<br />

woman and decides not to return. From this time onwards both factum and animus coexist<br />

and he becomes a deserter. A mere separation without necessary animus does not<br />

constitute desertion.[9] Both factum of physical separation and animus deserendi must be<br />

proved.[10] It is also necessary that there must be a determination to an end to marital

23<br />

relation and cohabitation. There is nothing like mutual desertion under the Act. One party<br />

has to be guilty.<br />

Burden of proof<br />

In case of desertion, the burden of proof lies upon the petitioner.[30] The petitioner is<br />

required to prove the four essential conditions namely, (1) the factum of separation; (2)<br />

animus deserendi; (3) absence of his or her consent (4) absence of his/her conduct giving<br />

reasonable cause to the deserting spouse to leave the matrimonial home. The offence of<br />

desertion must be proved must be proved beyond any reasonable doubt and a rule of<br />

prudence the evidence of the petitioner shall be corroborated.[31] In short the proof required<br />

in a matrimonial case is to be equated to that in a criminal case.<br />

Constructive desertion<br />

Where a situation or circumstances are created either by actual use of force or by the<br />

conduct of one spouse that the other spouse is compelled to leave the matrimonial home, it<br />

constitutes constructive desertion of the creator of the situation or circumstances. It is not<br />

necessary for the husband in order to desert his wife to actually turn his wife out of doors; it<br />

is sufficient if by his conduct he compelled her to leave the house.[32] It is now well settled<br />

that the matrimonial court has to look at the entire conspectus of the family life and if one<br />

side by his or her words or conduct compels the other side to leave the matrimonial home,<br />

the former would be guilty of desertion, though it is the latter who is seemingly separated<br />

from the other.[33] But where the husband does not take any steps to effect reconciliation,<br />

he is not guilty of constructive desertion.[34]<br />

The ingredients of both actual and constructive desertion are the same: both the elements,<br />

factum and animus must coexist, in former there is actual abandonment and in the latter,<br />

there is expulsive conduct. Under constructive desertion, the deserting spouse may continue<br />

to stay in the matrimonial home under the same roof or even in the same bedroom. In our<br />

country, in many homes husband would be guilty of expulsive conduct towards his wife to the<br />

extent of completely neglecting her, denying her all marital rights, but still the wife because of<br />

social and economic conditions, may continue to live in the same house.[35]<br />

Willful neglect<br />

It connotes a degree of neglect, which is shown by an abstention from an obvious duty,<br />

attended by knowledge of the likely result of the abstention. However, failure to discharge, or<br />

omission to discharge, every material obligation will not amount to willful neglect. Failure to<br />

fulfill basic marital obligations, such as denial of company or denial of marital intercourse, or<br />

denial to prove maintenance will amount to willful neglect.[43]<br />

Without the consent<br />

If one party leaves the matrimonial home with the consent of the other party, he or she is not<br />

guilty of desertion. When the parties are living apart from each other under a separation<br />

agreement, or by mutual consent, it is a clear consent of living away with the consent of the<br />

other. Wife when living away from the husband, husband sends a telegram ‘must not send<br />

wife’ to wife’s father expressed his wish to live separate.[45]<br />

Desertion must be for a continuous period of two years<br />

To constitute a ground for judicial separation or divorce, desertion must be for the entire

24<br />

statutory period of two years,[46] preceding the date of presentation of the petition.[47]<br />

Desertion is an continuing offence; it is an inchoate offence. This means that once desertion<br />

begins it continues day after day till it is brought to an end by the act or the conduct of the<br />

deserting party. It is not complete even if the period of two years is complete. It becomes<br />

complete only when the deserted spouse files a petition for a matrimonial relief. Wife’s act of<br />

withdrawing jewellary from the locker and remaining away from her husband for two years<br />

clearly proved her desertion.[48]<br />

Offer to return<br />

If a deserting party spouse genuinely desires to return to his or her partner, that partner<br />

cannot in law refuse to reinstate him or her.[49] An offer to resume cohabitation must be<br />

genuine or bona fide for which two elements must be present. First, an offer to return<br />

permanently, if accepted, must be implemented; secondly, it must contain an assurance as<br />

to the termination of the conduct by the deserting party which caused the separation.[50] A<br />

refusal to such an offer would convert the deserted party to the deserting party. The offer to<br />

return to resume married life by the deserting spouse before the expiry of the statutory<br />

period of desertion must not be stratagem. The deserting spouse must be ready and anxious<br />

to resume married life.[51]<br />

Defences to desertion<br />

The following are the main defences to desertion:<br />

v Agreement to separation does not amount to separation. But such agreement may be<br />

changed to desertion without resumption of cohabitation. Separation in such cases loses its<br />

consensual element.[52]<br />

v There may be animus deserendi without a separation.<br />

v Physical inability to end desertion, such as imprisonment.<br />

v Absence of just cause of separation.<br />

v Absence of animus deserendi.<br />

Termination of desertion<br />

Desertion is a continuing offence. This character and quality of desertion makes it possible to<br />

bring the state of desertion to an end by some act or conduct on the part of deserting<br />

spouse. It may be emphasized that the state of desertion may be put to an end not merely<br />

before the statutory period has run out, but also at any time, before the presentation of the<br />

petition.<br />

Desertion may come to an end by the following ways:<br />

(a) Resumption of cohabitation.<br />

(b) Resumption of marital intercourse.<br />

(c) Supervening animus revertendi, or offer of reconciliation.<br />

Resumption of cohabitation – if parties resume cohabitation, at any time before the<br />

presentation of the petition, the desertion comes to an end. Resumption of cohabitation must<br />

be by mutual consent of both parties and it should imply complete reconciliation. The<br />

desertion ends only when the deserting parties goes to the matrimonial home mentally<br />

prepared to end the cohabitation. It is necessary to prove that marital intercourse was also<br />

resumed.<br />

Resumption of marital intercourse – Resumption of marital intercourse is an important

25<br />

aspect of resumption of cohabitation. Sometimes resumption of marital intercourse may<br />

terminate desertion. If resumption of marital intercourse was a step towards the resumption<br />

of cohabitation, it will terminate desertion even if the deserted spouse backs out.<br />

Supervening animus revertendi – if the party in desertion expresses an intention to return,<br />

this would amount to termination of desertion. Animus revertendi means intention to return.<br />

Desertion may be brought to an end by the deserting spouse’s genuine and bonafide offer of<br />

reconciliation. It should not be just to forestall or defeat the impending judicial proceedings.<br />

4.8 Cruelty : a ground for matrimonial relief<br />

Every matrimonial conduct, which may cause annoyance to the other, may not amount to<br />

cruelty. Mere trivial irritations, quarrels between spouses, which happen in daytoday<br />

married life, may also not amount to cruelty. Cruelty in matrimonial life may be of unfounded<br />

variety, which can be subtle or brutal. It may be words, gestures or by mere silence, violent<br />

or nonviolent.<br />

To constitute cruelty, the conduct complained of should be "grave and weighty" so as to<br />

come to the conclusion that the petitioner spouse cannot be reasonably expected to live with<br />

the other spouse. It must be something more serious than "ordinary wear and tear of married<br />

life". The conduct taking into consideration the circumstances and background has to be<br />

examined to reach the conclusion whether the conduct complained of amounts to cruelty in<br />

the matrimonial law. Conduct has to be considered, as noted above, in the background of<br />

several factors such as social status of parties, their education, physical and mental<br />

conditions, customs and traditions. It is difficult to lay down a precise definition or to give<br />

exhaustive description of the circumstances, which would constitute cruelty. It must be of the<br />

type as to satisfy the conscience of the Court that the relationship between the parties had<br />

deteriorated to such extent due to the conduct of the other spouse that it would be<br />

impossible for them to live together without mental agony, torture or distress, to entitle the<br />

complaining spouse to secure divorce. Physical violence is not absolutely essential to<br />

constitute cruelty and a consistent course of conduct inflicting immeasurable mental agony<br />

and torture may well constitute cruelty. Mental cruelty may consist of verbal abuses and<br />

insults by using filthy and abusive language leading to constant disturbance of mental peace<br />

of the other party.<br />

Historical Position:<br />

Hindu marriage is a holy sacrament in the life of a Hindu with other various sacraments,<br />

which are known as important for the complete life. Marriage is the valid way for male and<br />

female to live together and perform their duties and husbandwife are considered to be one<br />

in law. In 1869 the Indian Divorce Act was passed but it had remained in applicable to the<br />

Hindus and after the Independence on 18th may 1955 The Hindu Marriage Act has been<br />

passes which governs all the matters and situations related to Hindu marriages.<br />

Impact of Physical and Mental Cruelty in Matrimonial Matters;<br />

Prior to the 1976 amendment in the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955 cruelty was not a ground for

26<br />

claiming divorce under the Hindu Marriage Act. It was only a ground for claiming judicial<br />

separation under Section 10 of the Act. By 1976 Amendment, the Cruelty was made ground<br />

for divorce. The words, which have been incorporated, are "as to cause a reasonable<br />

apprehension in the mind of the petitioner that it will be harmful or injurious for the petitioner<br />

to live with the other party".<br />

Legal Provisions:<br />

The Hindu Marriage Act1955 has given the legal provision for divorce on basis of cruelty<br />

under section – 13(1)(ia) as follows;<br />

“Any marriage solemnized, whether before or after the commencement of this Act, may, on a<br />

petition presented by either the husband or the wife, be dissolved by a decree of divorce on<br />

the ground that the other party has, after the solemnization of the marriage, treated the<br />

petitioner with cruelty”.<br />

On basis of this section we can explain this legal basis for the divorce as anybody who is<br />

getting suffer from the other party in physical manner or a mental torture or any other type of<br />

harassment then the other can reach to the court with this base and claim for the divorce.<br />

And there are various cases where courts held that the intention to be cruel is not an<br />

essential element of cruelty as envisaged under this section.<br />

4.9 Adultery : a ground for matrimonial relief<br />

Either party to the marriage may present a petition for divorce under cl. (i) of subsec. (1) of<br />

s. 13, on the ground of adultery of the respondent. The expression 'living in adultery' used in<br />

old s. 13(I)(i) meant a continuous course of adulterous life as distinguished from one or two<br />

lapses from virtue. It would not be in consonance with the intention of the Legislature to put<br />

too narrow and too circumscribed a construction upon the words 'is living' in (old) cl. (i) of<br />

subsec. (1) of s. 13 of the Act. On the other hand, it was clear that too loose a construction<br />

must also not be put on these words. For attracting the operation of these words, it would not<br />

be enough if the spouse was living in adultery sometime in the past, but had seceded from<br />

such life for an appreciable duration extending to the filing of the petition. It is not possible to<br />

lay down a hard and fast rule about it since the decision of each case must depend upon its<br />

own merits and turn upon its own circumstances. But it is clear that for invoking the<br />

application of (old) cl. (i) of subsec. (1) of s. 13, it must be shown that the period during,<br />

which the spouse was living an adulterous life was so related from the point of proximity of<br />

time, to the filing of the petition that it could be reasonably inferred that the petitioner had a<br />

fair ground to believe that, when the petition was filed, the respondent was living in adultery.<br />

By using the words 'is living in adultery' the Legislature did not intend to make such living<br />

coextensive with the filing of the petition. The identical expression of 'living in adultery' is to<br />

be found in s. 488(4) the Code of Criminal Procedure (old) and in s. 125(4) of the Code of<br />

Criminal Procedure (new). This expression implies that a single lapse from virtue even if true<br />

will not suffice, and it must be shown that the respondent was actually living in adultery with<br />

someone else at the time of the application. Living in adultery is different from failing to lead<br />

a chaste life.

27<br />

The expression 'living in adultery' refers to an outright adulterous conduct and the<br />

respondent lived in a quasipermanent union with a person other than the petitioner or the<br />

purpose of committing adultery. illicit conception, living as concubine or kept as mistress<br />

does not mean living in adultery. After the commencement of the marriage Laws<br />

(Amendment) Act 1976, even a single act of voluntary, sexual act by either party to the<br />

marriage with any person other than his or her spouse will constitute ground for divorce for<br />

the other spouse. But under the old law an isolated act of adultery did not attract the<br />

provision of s. 13(1)(i) of the Act, but provided a ground for judicial separation. To maintain a<br />

distinction between divorce and judicial separation e court should even in the context of the<br />

Marriage Laws (Amendment) Act 1976, put suitor construction for granting the decree of<br />

divorce than the decree of judicial separation. It is because the relation of the husband and<br />