sng_2016-05-12_high-single-crop_k3

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

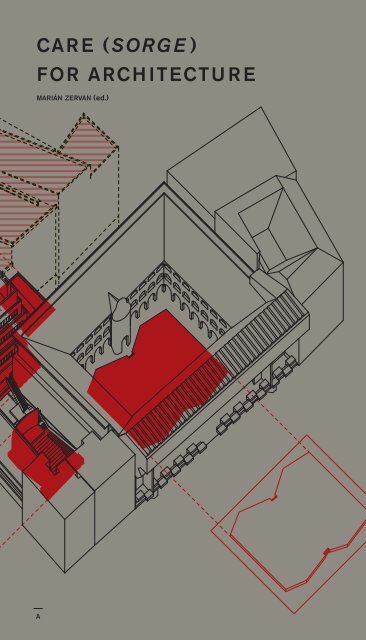

CARE (SORGE )<br />

FOR ARCHITECTURE<br />

marián zervan (ed.)<br />

a<br />

A

B

15. Mostra<br />

Internazionale<br />

di Architettura<br />

Partecipazioni Nazionali

Care ( Sorge ) for Architecture<br />

Asking the Arché of Architecture to Dance<br />

Pavilion of The Czech Republic and The Slovak Republic<br />

15th International Architecture Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia<br />

The Slovak National Gallery in Bratislava<br />

The National Gallery in Prague<br />

Ministry of Culture of The Slovak Republic<br />

Ministry of Culture of The Czech Republic

01. Statement p. 6<br />

marián zervan<br />

02. On the Slovak National Gallery site’s genesis, analysis and reflection p. <strong>12</strong><br />

monika mitášová<br />

03a. Textual Interpretation of Compositional and Clustering Arrangements p. 54<br />

marián zervan, monika mitášová<br />

03b. Architectural Interpretation of Compositional and Clustering Arrangements p. 66<br />

benjamín brádňanský, vít halada<br />

Co-authors : monika mitášová, marián zervan<br />

In collaboration with : andrej strieženec, mária novotná,<br />

anna cséfalvay, danica pišteková<br />

04. Chronology p. 94<br />

monika mitášová, marián zervan<br />

<strong>05</strong>. Project Description p. <strong>12</strong>8<br />

marián zervan<br />

06. Photos of the SNG Model p. 134

01.<br />

STATEMENT<br />

CARE (SORGE )<br />

FOR ARCHITECTURE:<br />

ASKING THE ARCHÉ<br />

OF ARCHITECTURE<br />

TO DANCE marián zervan

Architecture must never lose its project,<br />

or become paralyzed in solicitude (Fürsorgen),<br />

or get lost in concern (Besorgen) – rather it must<br />

find the courage to invite the arché to dance.<br />

— variations on heidegger<br />

We fill our lives more with metaphors<br />

on fighting than on dancing.<br />

— variations on lakoff<br />

7<br />

7

The idea to build the SNG (Slovak National Gallery) came about<br />

after the Second World War. An emerging society, art historians<br />

and architects were all making efforts. Each group had its own<br />

conception, and took its own small steps. Society passed legislation,<br />

and provided space in the former military Vodné kasárne<br />

(Water Barracks). The SNG director Karol Vaculík desired<br />

expansion of collections, and therefore of the Gallery’s space.<br />

Architects tried out various sites and forms for the Gallery.<br />

These steps led to the decision to form the new SNG site by<br />

remodelling and adding to the Baroque Water Barracks, and<br />

linking the public spaces of the city square adjacent.<br />

The new site, and its individual architectural components,<br />

came about in several stages through the 1960s and 1970s.<br />

The architect Vladimír Dedeček found a phased solution, both<br />

bold and unusual for its time. The building of a fourth and<br />

front-facing side to the Water Barracks, along with the opening<br />

up of the square as public space, inspired Dedeček to<br />

employ a bridge construction, which connected the two wings<br />

of the existing historical structure. He made this bridging into<br />

exhibition space for modern and contemporary art. In this he<br />

abandoned the classical structure of storeys, creating three<br />

levels of floors that formed a total space and three progressive<br />

unenclosed storeys. He shifted self-contained forms like the<br />

office building, the library and the originally-planned outdoor<br />

sculpture gallery in different directions. This made possible<br />

clusters of contemporary new architecture and abstracted<br />

classical forms of agoras, amphitheatres, odeón halls and<br />

stoas. For a decade, he laboured to push through a complex<br />

building/area site, but never succeeded in winning others over,<br />

even in terms of proposed materials and technologies. The ultimate<br />

result was imposing, but has from the first even until<br />

now been misunderstood by the public, and many of Slovakia’s<br />

architects. After 1989 there were thoughts to level the whole<br />

site and build a new gallery structure. Public surveys and discussions<br />

ensured, and from these there emerged a competition<br />

for a renovation and addition.<br />

8

The SNG building/area has long been seen as a nexus of<br />

multiple front lines: A) The struggle with prejudice and custom:<br />

generations of citizens are unable to overcome pseudo-historical<br />

beliefs in shaping the city, and hanker for conservation and<br />

restoration. B) Political disputes: after 1989’s Velvet Revolution,<br />

the site including the bridge was put forward as the embodiment<br />

of the monstrosities of the former (socialist/communist)<br />

regime and its aspirational megalomania. The political elite, with<br />

iconoclastic ambitions and rush to swap old models for new,<br />

wavered over what to do with the site. Only the next generation<br />

of architects, from here and abroad, proved able to de-politicize<br />

the issue of the SNG site, grasping it as a cultural and architectural<br />

challenge and opportunity. Then even the political elite<br />

saw it as an undertaking to be fostered. C) Developer power<br />

play: after 1989, building contractors and real estate developers<br />

in the new capitalism of post-socialistic countries came up<br />

with an ideological and pseudo-expert mask, intended to win<br />

commissions in favour of demolition. There is only one way that<br />

architects can contend with the combined forces of politicians<br />

and developers, and it is not in front-line words or even metaphors;<br />

rather they must do a verbal and metaphorical dance,<br />

in which no one is pushed and everyone voluntarily engages<br />

enjoyably in pursuing a common rhythm. D) Struggles among<br />

architects and pseudo-experts: architects and preservationists<br />

found themselves in mutually-incompatible discussions; in them,<br />

rather than looking for a project, they nitpicked at flaws in construction,<br />

technology and urban design, and suggested clearing<br />

the area and building a new SNG. On the other side were<br />

those who advocated in favour of the area as it is, who came<br />

to believe it could be saved only if they toned down the boldness<br />

of the problem. In the end it emerged that there were some<br />

who understood the SNG could only live through a renewal of<br />

Dedeček’s invitation to dance. Two architectural competitions<br />

for renovation came out of these discussions, for a refurbishment<br />

and an addition to the area, which would reflect the state<br />

of archi tectural thought in Slovakia.<br />

9

Competitions on renovation, refurbishment and addition to<br />

the SNG have opened new thinking processes on the Gallery’s<br />

spatial form. These processes are among the most significant<br />

architectural tasks being undertaken in Central Europe, comparable<br />

to solving the social and ecological issues of those living<br />

in our globalized world’s baser conditions and environs. We can<br />

never attain bold projects unless we understand the diversity of<br />

cultures. When the SNG site originated, it expanded the horizons<br />

of architectural awareness; now the competition designs<br />

for renovation have brought with them many questions and answers.<br />

Now as then, there are no universal solutions that can<br />

function in the absence of awareness of the cultural particulars of<br />

each society and environment – and particularly unless there is<br />

a dance, shared by architects, theoreticians and historians, and<br />

aficionados, who have the courage to take on public opinion.<br />

The construction associated with the SNG is not a battle<br />

over a <strong>single</strong> piece of architecture, though our history has many<br />

such stories. Here we have what is above all the meeting of two<br />

ways of thinking and building: fighting and dancing. Although<br />

the language of fighting remains common, we hope the language<br />

of dancing still has a chance. Therefore this is not just<br />

some chronicle of a building, or an appeal or complaint, or a record<br />

of the meticulous attention of preservationists and those<br />

devoted to historical replicas and unprocessed concern; rather<br />

the issue should be to imagine architecture’s potential. It is an<br />

awakening of hope, of care for architecture, which hopefully will<br />

be rid of the timidity manifested in pedestrian, generalized and<br />

participative pseudo-solutions, in order to once more find the<br />

courage to put forward intrepid cultural projects, countless invitations<br />

by arché to architecture to dance. This would make possible<br />

the reemergence of gaia architectura [ joyful architecture ].<br />

10

02.<br />

ON THE SLOVAK<br />

NATIONAL GALLERY<br />

SITE’S GENESIS,<br />

ANALYSIS<br />

AND REFLECTION monika mitášová

study for addition of southern/danube <strong>sng</strong> wing :<br />

Vladimír Dedeček, 1962 1<br />

study for the architects’ association zväz slovenských architektov :<br />

Vladimír Dedeček, 1963 2<br />

initial project, and alternative initial project :<br />

Vladimír Dedeček, 1967 3<br />

comprehensive project solution for project execution :<br />

Vladimír Dedeček (lead architect)<br />

and Peter Mazanec, Mária Oravcová, Ján Piekert (supporting architects)<br />

and X. ateliér školských a kultúrnych stavieb, 1969 4<br />

structural engineering project :<br />

Otokar Pečený, B.[?] Zuzánek, Jindřich Trailin (steel construction),<br />

Miloš Hartl, Karol Mesík, Mária Rothová (ferro-concrete construction)<br />

interior architecture project :<br />

Jaroslav Nemec<br />

1st stage<br />

− renovation of original building<br />

– depository, first section<br />

– exhibit building, addition of front wing (bridging)<br />

– heating plant<br />

2nd stage<br />

– research/administrative building – upper construction<br />

– depository, second section<br />

– restoration studios<br />

– photo laboratory<br />

– library, study and outdoor amphitheatre with cinema<br />

– lecture hall<br />

– studios<br />

3rd stage<br />

– variable building, with temporary exhibit space and main entry (not realized)<br />

4th stage<br />

– garage with terraced ground-level roof and outdoor sculpture gallery (not realized)<br />

general contractor :<br />

Stavoprojekt Bratislava<br />

13

investor :<br />

Povereníctvo pre školstvo a kultúru<br />

(after 1969 called the Ministry of Culture of the Slovak Socialist Republic)<br />

via the Slovak National Gallery in Bratislava<br />

construction :<br />

Pamiatkostav, n. p., Žilina and Hydrostav, n. p., Bratislava;<br />

additionally, Priemstav, n. p., Bratislava; Mostáre, n. p.,<br />

Brezno and Stavoindustria, n. p., Bratislava<br />

1st stage<br />

1969, 5 addition (bridging)<br />

and 1971, 6 renovation of Water Barracks – completed 1976 7<br />

2nd stage<br />

1972–1977 8 ( preliminary permission for use 1979, 9 final inspection 1980 10 )<br />

building volume (total built space ) :<br />

101,381 m 3<br />

expenses :<br />

approx. 106 mil. 350 thousand Kčs<br />

typology :<br />

Cultural sector project, a gallery area site with permanent<br />

and short-term art exhibitions<br />

14

1 Author’s dating: 1969–1978. In: Životopis z 26. novembra 1987.<br />

Fond Vladimír Dedeček, Zbierka architektúry, úžitkového umenia<br />

a dizajnu SNG. This was confirmed using an unpublished text<br />

[multiple authors]: Záverečné technicko-ekonomické vyhodnotenie<br />

dokončenej stavby “Rekonštrukcia a prístavba Slovenskej národnej<br />

galérie”. [THS, SNG, Stavoprojekt], Bratislava 1980, 22 numbered<br />

pages and appendices. In: Fond Vladimír Dedeček, Zbierka<br />

architektúry, úžitkového umenia a dizajnu SNG.<br />

2 Dated based on a published text by VACULÍK, Karol: Nové priestory<br />

a expozície Slovenskej národnej galérie. Výtvarný život, 22, 1977,<br />

vol. 7, pp. <strong>12</strong>–19.<br />

3 The investment was approved in 1965. In: [unsigned]<br />

Záverečné technicko-ekonomické vyhodnotenie dokončenej<br />

stavby “Rekonštrukcia a prístavba Slovenskej národnej galérie”.<br />

Cited in Note 1 above.<br />

4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 Ibidem.<br />

15

Building(s) and spatial relationships<br />

The new buildings of the gallery site area have been constructed<br />

around three public spaces, such that they connect the river<br />

banks with two of the city centre’s squares.<br />

The southern space, facing the river, is a rectangular courtyard,<br />

bounded by the historical building’s three wings and the<br />

new facing wing (bridging). The underground gallery depository<br />

lies underneath. At the courtyard’s centre is a raised plinth level<br />

planted with grass and trees, designed for outdoor sculpture<br />

exhibitions and visitor use (the reinstallation of the historical<br />

fountain, with a circular pool connected to the building’s air<br />

conditioning, was not realized in the courtyard because the investor<br />

altered the air conditioning plan 11 ). Thus the river bank<br />

area is connected to the gallery site via a “sculpture courtyard”<br />

and a view into the historical building.<br />

The second public space is an outdoor amphitheatre with<br />

cinema, west of the courtyard. It connects the southern facing<br />

wing (bridging) with the lower pavilion of the library and lecture<br />

hall in the taller northwestern administrative building (which<br />

houses restoration studios, a photo lab and a residential apartment<br />

flat). The amphitheatre’s side wall of perforated concrete<br />

forms allows a visual connectedness that parallels the river. The<br />

western side, adjacent Hotel Devín, also made allowance for<br />

outdoor sculpture installation (but this was not realized).<br />

The third public space on the north, behind the historical building,<br />

was designed as a terraced roof of garages and storage. The<br />

terraces’ walkable roofs and lawn was meant to be an outdoor<br />

sculpture gallery (this building was not realized; the site came to<br />

serve as a gallery car park). The northern terraces were designed<br />

to connect the river bank and the gallery site area, through several<br />

varying heights, and the historic city centre to the north.<br />

The main entrance to the gallery site from the river promenade<br />

was placed at its southwest corner, near Belluš’ Hotel Devín.<br />

A gallery of temporary exhibitions, or “Kunsthalle”, was designed<br />

16

to be on the floor above (the site’s whole corner section was<br />

not realized, and two apartment buildings from the 1940s remained).<br />

The main entrance became the side entrances and<br />

central entryway is from the courtyard / see p. 51 /.<br />

Situation<br />

A group of gallery buildings with public spaces, in the centre of<br />

Bratislava on the Danube River banks (previously known variously<br />

as Nábrežná ulica, Dunajské nábrežie, nábrežie Batthányiho,<br />

Fadruszovo, Jiráskovo, currently called Rázusovo). In addition<br />

to the river road, the site is bordered by the streets Riečna<br />

to the west, Mostová to the east, and Paulínyho-Tótha to the<br />

north. The streets connect the site to the east with Štúrova and<br />

to the north with the square Hviezdoslavo námestie.<br />

From the year 1700 a granary was located on SNG land, and<br />

later the town militia’s Vodné kasárne (Water Barracks). The<br />

four-wing Theresian barracks and it its square courtyard (1759–<br />

1763) has been attributed to the Viennese architect Franz Anton<br />

Hillebrandt. Its southern wing and parts of the eastern and western<br />

wings was demolished in 1941 when the river road was widened.<br />

<strong>12</strong> The remaining “three-wing” arrangement was used as<br />

11 The air system, by the French firm Tunzini, was to have been<br />

computer-controlled, with water pumped from a dedicated well.<br />

Expert analysis by the firm Strojexport Praha led them to select<br />

Weiss from Austria (which later changed its commercial name<br />

to ÖKG Grünbach), which planned a cheaper automatic/manual<br />

control system that pumped water from the adjacent Danube.<br />

The glass ceiling over the bridge’s exhibit spaces was sealed<br />

with permanent plastic silicon into full glass Weginplast walls by<br />

the Austrian firm Wegscheider Farben. For more see Záverečné<br />

technicko-ekonomické vyhodnotenie dokončenej<br />

stavby “Rekonštrukcia a prístavba Slovenskej národnej galérie”<br />

as cited in Note 1, pp. 7–8. An expert appraisal in 1990 found air<br />

condition unit consumption to be <strong>high</strong>er than what corresponded<br />

to the stated period of operation. Thus the less expensive air<br />

conditioning purchased and installed was in fact used.<br />

<strong>12</strong> HOLČÍK, Štefan. The gallery building also housed the Múzeum<br />

hygieny. Staromestské noviny newspaper, 20 October 2007.<br />

17

the arcaded palace with a “cour d’honneur”. The renowned cafe<br />

and dance hall “Espresso Taranda” rented space in the building<br />

until 1948 in the reinforced courtyard terrace. Around 1950, the<br />

historical barracks was first renovated to be used to preserve<br />

and present the Slovak National Gallery’s historical collections<br />

(František Florians and Karol Rozmány Sr were responsible for<br />

the design and renovation, 1949–1955).<br />

In the early 1950s, Professor Emil Belluš and his architecture<br />

students at the Slovak Technical University took part in site<br />

selection for a new SNG pavilion or addition. In the 1957–58<br />

academic year, Belluš published his studio’s student projects,<br />

suggesting two locations: the first was a new SNG pavilion<br />

construction at Gottwaldovo námestie (currently Námestie slobody),<br />

with a detached pavilion gallery becoming part of the<br />

new “technical university city” (the new neighbourhood around<br />

technical university buildings); the second was an addition to<br />

the historic Water Barracks, with the new addition expanding<br />

exhibition space for the gallery’s burgeoning collection in the<br />

historic building, and becoming part of the river promenade.<br />

In 1952, Vladimír Dedeček graduated under Emil Belluš’<br />

super vision, specifically with a thesis project on the Výstavný<br />

pavilón SNG (SNG exhibition pavilion) located at a third site:<br />

Kamenné námestie (the former Steinplatz, later Kiev Square)<br />

in Bratislava. After years of working with his students, Belluš<br />

made the following summary in the late 1950s: “[u]rban planning,<br />

architectural, operational and financial studies proved<br />

that the most realistic location for the expanded construction<br />

of the Slovak National Gallery is the current tract on Rázusovo<br />

nábrežie by the Danube, where a purposeful construction of<br />

a face wing can well assure the gallery’s growing needs, as well<br />

as creating an expedient and sufficiently spacious environment<br />

for occasional special exhibits and exhibits of contemporary art.”<br />

(BELLUŠ 1957, pp. 93–94.) This statement is in line with Belluš’ effort to<br />

complete a modernized river area with a new skyline, i.e. his abiding<br />

endeavour to finish a Danube promenade from Harminc’s<br />

18

uilding, currently housing the directorate of the Slovak National<br />

Museum (originally the agricultural museum) and the area of Park<br />

kultúry a oddychu (now being demolished). But, in Dedeček’s<br />

words, the main “inspiration for the idea to complete the SNG<br />

with a modern facing wing that would enclose the yard in the<br />

spirit of Hillebrandt’s original concept” was always the SNG<br />

director Dr. Karol Vaculík (DEDEČEK, undated [1975], p. 1).<br />

The contemporary guidelines Smernica pre výstavbu mesta<br />

Bratislavy, from a group led by the city’s chief architect Milan<br />

Hladký and chief city planner Milan Beňuška in October 1963,<br />

states: “In terms of political administration, the commercial<br />

and social centre should be developed in the context of the<br />

current centre, expanded to subsume the tracts attached to<br />

the Danube at Podhradské nábrežie and near the harbour, reassessing<br />

the meaning of the Danube river area, building it<br />

up as the city’s most frequented zone and thus emphasizing<br />

the <strong>high</strong>ly social function of these spaces... By 1970, a road<br />

bridge to be constructed over the Danube in the Rybné námestie<br />

space.” 13 Thus some of the riverbank’s historical architecture<br />

was, in keeping with 1960s urban plans, demolished,<br />

in part in connection with the Most SNP bridge construction.<br />

Among these were burgher residences on Lodná ulica behind<br />

Belluš’ Hotel Devín; some of the residences survived on Ulica<br />

Paulínyho-Tótha, but the breadth and scale of the riverside had<br />

changed. In this spirit, in 1965 the Slovenský ústav pamiatkovej<br />

starostlivosti (the historical sites institute) issued the following<br />

judgment on modernizing and refurbishing the riverside,<br />

and Dedeček’s study for SNG renovation and construction:<br />

“In principle, the view of this comprehensive urbanism solution<br />

for the entire block and the modernity of the architectural style<br />

is correct; the historical buildings in this quarter are physically<br />

worn, and disrupt the additional new construction that would<br />

13 BEŇUŠKA, Milan – HLADKÝ, Milan. Smernice pre výstavbu mesta<br />

Bratislavy. Bratislava : Útvar hlavného architekta mesta Bratislavy,<br />

October 1963, p. 10, 15 and 22.<br />

19

give the quarter a new scale and expression, and furthermore<br />

from the perspective of historical site significance they are of<br />

little value and not studied by preservationists.” (The institute’s<br />

director at the time was Ing. arch. Ján Hraško.) 14<br />

Regarding preservation studies, the statement goes on<br />

to identify just two historical buildings: the renovated “late<br />

Renaissance” Water Barracks and the dilapidated “neoclassical<br />

building” of the former horse railway terminus close to the<br />

Hotel Carlton Savoy. Dedeček had the latter documented (as<br />

part of the SNG reconstruction and addition project), but it was<br />

taken down because the ceilings’ structural integrity was unsound.<br />

The residential buildings on Ulica Paulínyho-Tótha were<br />

at the time considered “unworthy of preservationist study”, to be<br />

“purged” for the sake of both the Water Barracks and Harminc’s<br />

addition and interconnection of three of Bratislava’s hotels, the<br />

Carlton, the Savoy and the National, into a <strong>single</strong> modern hotel<br />

(project 1927, realization 1928). With this intervention, Harminc<br />

fundamentally changed and shifted the scale of the Hviezdoslavo<br />

námestie square. Thus it was not just Professor Belluš’ Hotel<br />

Devín, but also his generational predecessor’s triple hotel Carlton<br />

Savoy ( National ) that had greatly outdone the surrounding<br />

buildings in size and scale – indeed, by the 1930s a new urban<br />

and architectural dimension had taken hold on the modernized<br />

riverfront, which around 1950 Belluš affirmed and elaborated<br />

with his Hotel Devín. Bratislava’s riverbank, touching its historical<br />

core, had taken on new significance as a city promenade,<br />

bringing the river’s presence right to Hviezdoslavovo námestie.<br />

This modernized riverfront took on a new line, height and volume<br />

of buildings, but also a new urban, social and recreational meaning<br />

for its citizens. It was another step toward the city’s later<br />

expansion to the other bank of the river, into Petržalka.<br />

20

Program and spatial solution<br />

The genesis of the Slovak National Gallery as an institution<br />

drew, as many authors including Emil Belluš have noted, on the<br />

exhibition activities of Slovakia’s first independent “centre” of<br />

Slovak and Czech artists in the Umelecká beseda slovenská (by<br />

Alois Balán – Jiří Grossmann, competition project 1924, realization<br />

1925–1926) on Šafárikovo námestie near the Danube.<br />

Of it, Belluš wrote in 1957: “Though it had long been riven by<br />

political courses, there was such an upsurge in the life of art<br />

in Slovakia under the new conditions that the auspicious exhibit<br />

pavilion within a few short years to be insufficient.” (BELLUŠ<br />

1957, p. 91) In 1933 the first permanent installation of Slovakia’s<br />

19 th and 20 th century painters came about, called The National<br />

Slovak Gallery, in Harminc’s newly completed National Museum<br />

in Martin. Ten years later, a Slovak Gallery opened in the Slovak<br />

National Museum on the banks of the Danube in Bratislava. But<br />

as an independent institution, the SNG – founded in summer<br />

1948 – received new tasks: “It was a great disadvantage that<br />

Slovakia had a late start in putting together a representational<br />

national art collection. It was also disadvantageous that the<br />

SNG came about through a process opposite to most European<br />

galleries: not through an accumulation of [art] objects that<br />

forced the inception of a public collection, but by founding an<br />

institute for the purpose of originating a coherent collection.”<br />

(VACULÍK 1957, p. 78.)<br />

A secondary aspect of this late founding of the Slovak<br />

National Gallery institution was that, along with the national<br />

archive, there was no initial chance for this gallery to be located<br />

in a suitable historical palace or monastery complex, as had<br />

been the case with Slovakia’s national and state institutions<br />

14 Opinion of the director (name not shown, signature illegible<br />

[possibly Ing. arch. Ján Hraško /?/]) of the Slovenský ústav<br />

pamiatkovej starostlivosti a ochrany prírody, dated in Bratislava<br />

11 January 1965 and sent to the SNG and Bratislava's chief<br />

architect's office. Typewritten, 2 pages. In: Fond Karol Vaculík,<br />

Archív výtvarného umenia SNG.<br />

21

founded earlier. Therefore construction of a new gallery building<br />

brought with it the advantage of allowing formulation of<br />

a new architectural undertaking. 15 The need was defined for<br />

a localization of art depository, restoration, study/research and<br />

exhibition spaces that would also provide sufficiently variable<br />

indoor and outdoor galleries, of a nature that refurbished buildings<br />

originally serving as residential and service wings in palaces,<br />

monasteries or barracks could not offer. For instance, the<br />

investor responsible for the new Slovak National Archive sought<br />

architecture in the spirit of the contemporary building of Matica<br />

slovenská in Martin (by Dušan Kuzma – Anton Cimmermann,<br />

competition project 1961–1962, realization 1963–1975) rather<br />

than complicated connection to or renovation of the capital’s<br />

various historical structures.<br />

Years of preparations led to the government’s proposal, through<br />

the Slovak parliament’s schools and culture commission on<br />

28 December 1962, to build on the historical Water Barracks,<br />

directing the responsible minister Vasil Bil’ak to begin preparations<br />

and include the construction in the budget. Based on this<br />

the SNG’s director, Dr. Karol Vaculík, called for an initial proposal<br />

(comparison study) to build Vladimír Dedeček’s southern,<br />

Danube-oriented wing onto the barracks. In 1962 Dedeček submitted<br />

a first alternative for the wing, as a Le Corbusier-esque<br />

functionalist building on pilotis with open parterre and a flat roof.<br />

Here the exhibition floors were not lined up, but rather shifted<br />

in two directions, such that natural light from above illuminated<br />

them / see architectural interpretation, p. 76, pict. B /.<br />

The architects’ association Sväz slovenských architektov<br />

(SSA), drawing on Bratislava’s urban planning guidelines, extended<br />

Vaculík’s program to include building an entire city<br />

block; in 1963 they compiled a study for the gallery’s addition<br />

and renovation (THURZO 1978, p. 4). Four groups were invited to propose:<br />

one under Jaroslav Fragner of Prague’s Academy of Fine<br />

Arts architecture school; under Eugen Kramár of Stavoprojekt<br />

Košice; under Martin Beňuška and Štefánia Rosincová of both<br />

22

Bratislava’s chief architect’s office and Stavoprojekt Bratislava;<br />

and finally X. ateliér vysokoškolských a kultúrnych stavieb under<br />

Vladimír Dedeček of Stavoprojekt Bratislava.<br />

The selection of comparative studies consulted with the association<br />

differed from the standard architectural competition<br />

in that the SSA association’s commission was able to consult<br />

the studies with the four groups when they created them, then<br />

compare them continuously and ultimately announce a winner.<br />

Thus there was in fact a two-round consultative selection process<br />

ending in a vote. Vladimír Dedeček’s study was chosen:<br />

there was a first alternative for the site (with a second alternative<br />

for the southern wing adjacent the Danube on pilotis), expanded<br />

to include completion of a city block with an outdoor terraced<br />

sculptured gallery to the north, toward the historic core. The SSA<br />

commission was chaired by Štefan Svetko, then the director of<br />

Bratislava’s chief architect’s office; the other members were<br />

Alojz Dařiček, Ján Steller, L’ubomír Titl and Milan Škorupa. 16<br />

In the sense of this “consultative selection by voting”, the architect<br />

Dedeček’s introduction to the project’s text distinctively noted:<br />

“This study’s working method is discussion. The discussion’s<br />

individual phases and arguments are present in the visual material...”<br />

(DEDEČEK 1963, p. 1). This formulation, and archive documents<br />

on the commission’s work, make clear that the consultations<br />

yielded a first concept for the area, considered fitting by both<br />

commission and investor for preparing the investment plan and<br />

an initial project. Vladimír Dedeček consulted the subsequent<br />

investment plan (approved in 1965) and initial project (approved<br />

15 An oft-cited text by Dr. Martin Kusý stressed as much: KUSÝ,<br />

Martin – GRÁCOVÁ, Genovéva. Slovenská národná galéria.<br />

Slovensko, 1, 1977, vol. 3, pp. 4–5.<br />

16 See the SSA minutes Zápisnica z 1. konzultácie posudzovacieho<br />

sboru so spracovatel’mi študijnej úlohy na doriešenie SNG<br />

v Bratislave, konanej dň a 17. septembra 1963 na sekretariáte<br />

SSA v Bratislave. Typewritten, p. 2. In: Fond Karol Vaculík.<br />

Archív výtvarného umenia SNG. See also Záverečný protokol<br />

from the assessment of studies, dated 16 December 1963,<br />

3-4 and 6 January 1964, at the SSA secretariat. Typewritten,<br />

p. 9. In: Fond Karol Vaculík, Archív výtvarného umenia SNG.<br />

23

in 1968) in 1966–1967 with the gallery director Dr. Vaculík, who<br />

considerably influenced the project’s character. This was a longterm<br />

working discussion between the architect and those who<br />

commissioned and financed the construction, and also included<br />

other architects and city planners selected by the SSA.<br />

The next step in building this gradually-designed and -consulted<br />

national gallery project was inclusion in investment<br />

budget planning and allocation of finances. Dr. Vaculík and the<br />

associations of Slovak and Czech artists – like other investors<br />

of prestigious buildings of national significance – several times<br />

requested government and state leaders for financial assistance<br />

to launch and maintain the gallery construction. 17<br />

Later the architect, in part responding to criticism, was to call<br />

the first alternative, with the second alternative for the Danube<br />

wing on pilotis, “... sober, and let us say to some extent conservative.”<br />

(DEDEČEK, undated [1975], p. 3). For all that, a pilotis construction<br />

was being placed next to Belluš’ 20 th century classicized functionalist<br />

hotel, with its terrace near the Danube. The floors were<br />

shifted in two directions, so as to benefit from top lighting and<br />

give the extensive wing a broken-field bulk and mass: “The technical<br />

purpose endows the mass with a plastic tone. The steel<br />

construction makes this solution possible.” (DEDEČEK 1967, p. 1)<br />

Dedeček harmonized the new solution to the construction and<br />

mass/spatial issues of the exhibition spaces in the Danube wing<br />

with the Hotel Devín to the west and the Esterházy palace to the<br />

east by means of several contextual choices: through respecting<br />

the new line of the street, the height of Esterházy palace<br />

gabling, the modernizing scale of Hotel Devín, and a design of<br />

an analogous facade – for like Belluš’ hotel, the gallery project<br />

was meant to be faced with stone from the Spišské Podhradie<br />

travertine field.<br />

The architect had first tried out staggered storeys in connection<br />

with top natural lighting for the classrooms and teacher<br />

rooms in the Secondary economics school / 33-class economics<br />

school building on Ulica Februárového vít’azstva (now the<br />

24

Obchodná akadémia on Račianska). The arrangement of mass<br />

and space in this school was thus a foretaste of the Danube<br />

wing gallery exhibition space and a turning point in the context of<br />

the architect’s later work. In working with daylight for the top and<br />

combined interior lighting, which directly influenced the differentiation<br />

of the buildings individual storeys, the architect was responding<br />

to the other zones and buildings around. Interestingly,<br />

he developed the idea to a large extent in the partially-realized<br />

project of Forestry and wood processing university in Zvolen,<br />

in the unbuilt central university library building.<br />

Even in his first alternatives for the SNG completion, Dedeček<br />

emphasized a series of interior and exterior “gallery squares”, and<br />

their relation to “town squares”. It was these urban “art exhibition<br />

environments” of Dedeček’s that enfolded the individual gallery<br />

building wings, and opened up the compact barracks block,<br />

17 SNG archives have preserved a letter from Dr. Vaculík to the<br />

culture minister Miroslav Válek dated 31 October 1969, in which<br />

he requests the minister to “... intervene energetically and assist<br />

in this matter”. Typewritten, 3 pages. In: Fond Karol Vaculík. Archív<br />

výtvarného umenia SNG. [In it, Vaculík explains to Válek the crisis<br />

of the threatening halt of the incomplete construction, and the<br />

disproportion between the real costs and the underestimated<br />

first phase budget (made so the investment could be held to<br />

under 40 mil., meaning the Slovak culture ministry – back before<br />

the Federation was established – would not have to get approval<br />

from the “Prague government”). He also informed the minister<br />

that Comrades Peter Colotka and Július Hanus had promised to<br />

arrange for the project to be included at the soonest government<br />

cabinet meeting. Similarly, Comrade Štefan Šebesta, minister<br />

for construction and technology, promised to help Vaculík. At the<br />

same time, it was noted a delegation of functionaries from the<br />

association of Czech and Slovak artists had “some time ago”<br />

discussed the issue of the President of the Republic. The President<br />

(Antonín Novotný until March 1968, then Jozef Lenárt as Acting<br />

President from 22–30 March, and Ludvík Svoboda from March<br />

1968) proposed linking the construction of the National gallery<br />

in Prague and in Bratislava in one nationwide undertaking, so as to<br />

finance it from the Republic Fund. Vaculík considered this feasible.<br />

By then the steel bridge had been commissioned and mostly<br />

built (cost 10 mil. Kčs), with a planned delivery to the building site<br />

of early 1970. Vaculík was appealing to Válek that construction<br />

not be halted, as this would misspend invested financies, and the<br />

painstakingly assembled structure of suppliers would collapse .]<br />

25

with its central square, to a field of checkerboard-like differentiated<br />

environments with a variety of levels and means of moving<br />

around (covered walkways, passages, loggias, stairways, ramps,<br />

raised pedestals/plinths, rooftop terraces, walkable roofs and<br />

so forth). Such urban links at diverse heights made it possible<br />

to perceive the art, the site and the city from varying elevations:<br />

it even afforded views of adjacent riverfront buildings, the river,<br />

the streets of the historical city core, and the growing city space<br />

on the other bank of the Danube.<br />

The purpose of a gallery site area so designed was both<br />

to provide for indoor exhibitions in the gallery’s own buildings,<br />

but to connect them to outdoor exhibitions “in among” buildings,<br />

on them and under them, in open passageways. Thus it<br />

was not just Dedeček’s buildings themselves that enabled and<br />

enclosed the exhibition space, but vice versa too: Dedeček’s<br />

urban exposition environment in public space turned the gallery<br />

into an indoor-outdoor art exhibit along the river. It could be said<br />

that the site stimulated the relationships between the outdoor<br />

modern sculpture exhibits and the plasticity of late modern<br />

architecture; it could also be said that the site as it was designed<br />

with consideration for exhibiting historical and modern<br />

sculpture right in the city, even anticipating exhibition of new<br />

types and genres of art: environments and installations in situ<br />

alongside series and accumulations of artworks. The summer<br />

amphitheatre brought in the cinematic art. So this was a comprehensive<br />

and innovative urbanist/architectural space, intended<br />

even for new audio-visual arts, accessible in a new urbanist/<br />

architectural situation. However, in the 1980s, after Dr. Vaculík<br />

was removed from the gallery’s leadership and the construction<br />

was completed, the spaces were not utilized as variably and<br />

innovatively as the site’s urban/architectural plan envisioned.<br />

Using the gallery area’s system of interior and exterior walkways,<br />

ramps and stairways, the public could walk from and to the riverfront<br />

to Štúrovo or Hviezdoslavovo námestie. A system of buildings<br />

thus designed, and their interstices, is an exquisitely urban<br />

26

gallery, a public space of multiple focal points, with focal points<br />

linked and even crisscrossed. Any effort by the gallery’s administrators<br />

or renovators to “enclose” the gallery as designed, to<br />

fill its “gallery squares” with indoor exhibit spaces, would run<br />

counter to the gallery’s concept of a distributed and crisscrossing<br />

plan; to use Aldo van Eyck’s phrase, counter to the “labyrinthine<br />

clarity” of its indoor and outdoor walkways, spaces and<br />

interstitial spaces.<br />

Seen in this light, the group of gallery buildings and their<br />

public spaces constitute a <strong>high</strong> point in Dedeček’s program to<br />

dislocate the urban mono-block (in urbanist and architectural<br />

terms) into a cluster that he had begun to formulate and prove<br />

as a counterpart to tried and true compositional approaches<br />

in primary and secondary schools, and continued in later university<br />

areas. The opened raster of SNG spaces is one – and<br />

the meandering pavilions of the Comenius University Natural<br />

Science faculty in Bratislava-Mlynská dolina another – of these<br />

interpretations: another of Dedeček’s solutions to his self-assigned<br />

task of rethinking relations between urban architectural<br />

openness and closedness. Ultimately, the interconnection of<br />

gallery and public space in the SNG project was not to change,<br />

from its earliest proposed alternatives through a fragmentary<br />

realization, despite the turbulent metamorphosis of the whole.<br />

A group of experts of the culture and information ministry gave<br />

approval to the introductory project as prepared (the first alternative<br />

for the area and the second alternative for the southern<br />

wing) in 1967: Professors Emil Belluš and Vladimír Karfík, the<br />

architect and urban planner Štefan Svetko, the construction engineer<br />

Jozef Harvančík and the architect Anton Cimmerman (Jozef<br />

Lacko excused himself). 18 Of their decision, Vladimír Dedeček<br />

wrote: “In scale and material we accommodated primarily to<br />

the principles applied in realizing Hotel Devín. The technical<br />

and financial council of the culture ministry, which included<br />

[H]otel Devín’s architect Prof. Belluš, opposed this as some-<br />

18 / see p. 29 /<br />

27

thing that had been outlived in the current rapid developments<br />

in architecture.” (DEDEČEK, undated, p. 4) In other words, this group in<br />

July 1967 was already considering Dedeček’s five-year-old conception<br />

for the SNG front wing on pilotis as a thing outdated,<br />

and called for its innovation. This shows the dynamic changes<br />

in architectural thinking in 1960s Slovakia. In his expert opinion<br />

on construction of the SNG addition, Jozef Harvančík stated:<br />

“... from the perspective of construction, the project features<br />

a desirable unity between technological conception and architectural<br />

expression that is noteworthy for our age. On these<br />

grounds I advocate project approval.” 19 In his opinion, Marián<br />

Marcinka commented mainly on the tall research/administrative<br />

building: “The effort at freeing up the ground level is a worthy<br />

aspect of the design: detaching the mass from engineering<br />

networks, and trying to overlap indoor and outdoor spaces<br />

at ground level; and the liberating maintaining of the gallery’s<br />

individuality and retaining of spatial association between the<br />

current gallery and the river bank... Interesting and resourceful,<br />

too, is the conception of mass of the exhibition portion<br />

from the banks of the Danube, with a calming, dignified and<br />

monumental effect. However, I cannot rid myself of the feeling<br />

that there is still a detail missing overall, something that<br />

would bring everything together... The administration building’s<br />

material solution, and its indoor spatial layout, is not convincing,<br />

seeming not to attain the quality of the other portions, and<br />

fails to come up to the solution of the whole. There is a kind<br />

of incongruity of architectural emphasis on the height of something<br />

that in its content is less essential (administration, photo<br />

lab, residences and the like). I do not think the gallery should<br />

show its architectural authority by emphasizing its height.” 20<br />

Marcinka’s opinion recommended approval, along with setting<br />

interim deadlines for reacting to such suggestions.<br />

A third opinion of an unidentified institution, with unidentified<br />

signature, expressed similar reservations: “The construction<br />

overall is logical in terms of operations and disposition, as it<br />

builds on the existing structure and in a fitting manner places<br />

28

the individual functional units (exhibition spaces, so-called<br />

administrative block, and garages). Automobile and pedestrian<br />

transport is optimally resolved, as are the proposed entrances<br />

to each unit. The garage’s location and architectural concept<br />

is especially good. What is debatable is the material solution<br />

of ‘administrative’ operations; and the architectural material<br />

completion of Phase I of construction remains an unresolved<br />

problem – i.e. that which is the subject of actual building work,<br />

and its relations to existing well-preserved residential houses<br />

on the corner by Hotel Devín. We cannot agree with the implicit<br />

cutting off of volumes by the attic walls.” 21 This third opinion’s<br />

conclusion included no final evaluation as to approval.<br />

18 See enclosures to Dr. Karol Vaculík's letter to Vladimír Dedeček of<br />

4 September 1967, typewritten, 19 p. It features the expert opinions<br />

of Jozef Harvančík and Marián Marcinka, and a third opinion from<br />

an unspecified institution with an unidentified signature. It also<br />

includes the opinion of Slovakia's historical sites institute with<br />

an unidentified director's signature [at the time, the director was<br />

Ing. arch. Ján Lichner, CSc.]. All these documents are copies of<br />

originals. In: Fond Karol Vaculík. Archív výtvarného umenia SNG.<br />

Because this was a new introductory project, the group of experts<br />

recommended a new appraisal of the second alternative, which was<br />

to take place at the ministry's administrative/technical commission<br />

on 1 August 1967. They additionally requested an opinion from<br />

the construction concern Pozemné stavby, národný podnik<br />

Bratislava, and the chief architect's office in Bratislava. Neither<br />

Dedeček nor the experts participated in these proceedings.<br />

Those present were: Dr. Karol Vaculík, František Baláž, and<br />

Ján Matúšek on behalf of the investor; Viktor Faktor, chief<br />

of operations for the lead architect, Dedeček's studio X. ateliér;<br />

Jozef Vaňko for Slovakia's construction commission; and<br />

Ing. arch. Marcinková, Ing. Šurinová, Ing. Magdalík, Ing. Ján Fišer<br />

and Milan Jankovský, for the culture ministry. The commission<br />

recommended approval of the developed introductory project.<br />

In: Fond Karol Vaculík. Archív výtvarného umenia SNG.<br />

19 HARVANČÍK, Jozef. Posudok konštrukcií v Úvodnom projekte<br />

Slovenskej národnej galérie v Bratislave pre Povereníctvo kultúry<br />

a informácií. 10 July 1967, typewritten, 3 p. In: Príloha listu<br />

Karola Vaculíka Vladimírovi Dedečkovi, 4 September 1967,<br />

typewritten, 19 p. Ibidem.<br />

20 MARCINKA, Marián. Vyjadrenie k úvodnému projektu<br />

na prístavbu Slovenskej národnej galérie v Bratislave.<br />

Undated, typewritten, 3 p. Ibidem.<br />

21 [unspecified institution] Vyjadrenie k PÚ-SNG. 30 June 1967,<br />

typewritten, 4 p. Ibidem.<br />

29

The commission discussed these expert opinions with the<br />

architect on 1 July, and 14 July 1967 was set as deadline for<br />

checking on project adjustments. Dedeček, responding to the<br />

opinions and the discussion, prepared over these 14 days a new<br />

alternative design (second area alternative, with third alternative<br />

for the Danube wing). In his new Technical report he stated:<br />

“Comrade Ing. arch. Svetko expressed reservations to the 4 m<br />

under-passage under the mass of exhibit spaces [i.e. to the<br />

colonnade in the Danube wing parterre], which in his opinion<br />

did not sufficiently visually connect the Taranda spaces with the<br />

riverbank’s; further, compared to the architectural solution of<br />

enclosing the SNG atrium with the new building, the proposal<br />

is not sufficiently organic.” 22 Dedeček reacted by raising the<br />

space under the Danube wing, creating: “... a 3-level bridge in<br />

front of the current [historical building’s] SNG, enabling visual<br />

connection between viewers by the Danube and the entire<br />

SNG space, which would then be visible up to the cornice<br />

(given that the courtyard vegetation so allows). The height of<br />

the opening [under the bridging is now] approximately 7.80 m.<br />

There are no supports in this space, enhancing the perception<br />

of the courtyard. (...) A courtyard spectator sees the new and<br />

old roofs at almost the same angle. This also improves the access<br />

of sunlight to the atrium; at the same time, this change<br />

reduces the total floor space, and one level is eliminated by<br />

increasing the opening. (...) Though the experts’ suggestions<br />

are at odds with the opinion of the jury and the advisory body of<br />

studies [of the architects’ association], I accept them because<br />

they reduce expenses, which in this situation will seem beneficial.<br />

I believe this had led me to a more interesting conception,<br />

with a similar volume composition for all sections.” 23<br />

Thus the Danube wing’s new space and arrangement came<br />

about through elimination of the lowest storeys, and a new<br />

conception of design of exposition spaces (the 3-storey wing<br />

became an open hall divided into 3 levels of ascending walkways).<br />

This new design also called for a new steel construction<br />

free of middle supports. The composition of the “bridging’s”<br />

30

arrangement into the riverfront, on the one hand, is the result<br />

of earlier solutions of sandwiched storeys, and on the other is<br />

a new diagonal bevelling resulting from the contours of sunlight<br />

coming into the space under the “bridging”. I.e., this was not just<br />

a matter of keeping to the construction/physical diagram of the<br />

lighting, which might be architecturally interpreted variously. The<br />

diagonal bevelling form is moreover an indication of the steel<br />

bridge structure’s ability to carry the spaces with no central<br />

supports, such that the parterres are opened, with no shadowing,<br />

and no blocking of pedestrians from the street, all while<br />

providing a new layer above ground and air of urban functions,<br />

right in the historical core, with all its usual density of habitation<br />

and construction... In other words, the SNG bridging, frequently<br />

regarded as an “expressive” or even “aggressive” form, is in<br />

fact exquisitely urban, in that it leaves open and accessible the<br />

courtyard space in the parterre, in this sense a form “social” and<br />

cultured. And this is the cultural and civilizational sense of the<br />

word urban – i.e. the cultural and social emancipation of the city<br />

from the nature-bound inevitability of respecting the action of<br />

natural forces. But this bridging quality can be seen and appreciated<br />

only if the citizens look not just at what the gallery bridge<br />

dismantled and halted, but also at what it to the contrary did<br />

not halt, at what it carries and how it rounds out the Bratislava<br />

riverfront. The modern bridging of the historical structure comes<br />

to the forefront if we look at the very nature of the public space<br />

it helps to shape and supplement, and not just as a thing in itself<br />

with its demolished predecessors. Based on the expert opinions,<br />

the architect lowered the administrative building from the<br />

requested 8 storeys to the current 6, and finished the structure<br />

with a flat walkable roof with skylights for the restoration studios<br />

and a tall attic with a Le Corbusier-esque “window” toward the<br />

castle and the opposite river bank.<br />

22 DEDEČEK, Vladimír. Technická správa k alternatívnemu riešeniu<br />

ÚP SNG. 11 June 1967. typewritten, 2 p. In: Fond Vladimír Dedeček,<br />

Zbierka architektúry, úžitkového umenia a dizajnu SNG.<br />

23 Ibidem, p. 1.<br />

31

In late 1969, i.e. after Czechoslovakia’s occupation by Warsaw<br />

Pact armies, a newly-named expert commission evaluated the<br />

resulting alternative based on project documentation.<br />

A new opinion from the preservation institute, with an unreadable<br />

signature (Ing. arch. Ján Lichner, Csc. was then director),<br />

reproached the lack of consultation with that institute on<br />

the new design, created in 14 days. For this reason the institute<br />

refused to give an overall position, expressing itself only “... from<br />

the limited perspective of preserving cultural heritage sites as<br />

registered by the state. Referring to the opinion of 11 January<br />

1965 we have no objections in principle to the solution of the<br />

new addition’s integration into the historical cultural site, though<br />

we are not expressing any opinion on the proposed architecture.<br />

Because of generally known technical circumstances, and the<br />

fact that the historical portion’s interior disposition and vaulting<br />

system has already been interrupted, we do not demand a strict<br />

preservation of vaulting on the west wing’s upper floor. However<br />

we ask that the courtyard’s facade expression with its central<br />

feature of a suggested building (chapel 24 ) be preserved, and<br />

the vaulting system of the arcaded corridors. In conclusion, we<br />

hold that from the perspective of preserving cultural heritage<br />

there are no objections in principle to the project submitted, and<br />

we agree with the given request.” 25 As in the previous opinion,<br />

there was no request here that there be a larger view through the<br />

courtyard to the historical building arcades.<br />

Interestingly, Dedeček’s study from back in 1963 included<br />

a view into the courtyard, at the height of one storey; the first<br />

SSA association commission chairman Štefan Svetko consistently<br />

advocated for two things throughout the evaluation: a view<br />

through to the building and eventually an enlarged view – along<br />

with a newer, more contemporary expression of the facing wing<br />

(!), something that by the late 1960s corresponded not just to<br />

Belluš’ classicized functionalist hotel, or to Le Corbusier’s five<br />

points of modern architecture, or to Dedeček’s own program of<br />

dissipating the mono-block, but rather to the dynamic of transformations<br />

in late 1960s architecture in Europe and the world.<br />

32

The second group of experts thus late in 1969 essentially<br />

merely confirmed the discussion between Dedeček, Cimmermann,<br />

Harvančík, Marcinka, Svetko, Karfík and Belluš on<br />

completing the SNG, of which only partial records have been<br />

archived. These discussions played a formative role in the later<br />

1960s in the project’s metamorphosis. Thanks in part to them,<br />

during the design phase the construction departed from one<br />

stage of late modern architecture in Slovakia, and moved into<br />

another: some would now call it communistic, totalitarian and<br />

“normalizing”, while others consider it a variation or derivation<br />

of what was happening in architecture internationally, especially<br />

in Europe. For the former group, it is most particularly a mirror<br />

image of the politics of the socialistic “normalization” of the city<br />

and the state; for the latter, it is was reaction to the example set<br />

by 1960s architecture internationally, on the other side of the<br />

iron curtain – usually without considering Dedeček’s long-term,<br />

systematic development of how he looked at architecture and<br />

architectural design of SNG / see Textual Interpretation of Compositional and<br />

Clustering Arrangements, p. 55–65 /.<br />

Module, construction, volume, surfacing<br />

The subterranean construction of additions to the historical<br />

building are of ferro-concrete, and those above ground<br />

are atypically steel-based. Regarding the bridging, “... this<br />

is a kind of three-level steel bridge of framed joists, laid on<br />

2 abutments, fixed and socketed”. (DEDEČEK – PIEKERT 1968, p. 2.) The<br />

administrative building was designed as “... a steel, five-floored<br />

[i.e. six- storeyed] frame with consoled, phased shifting of the<br />

forefront toward Hotel Devín, with a brick cladding”. (DEDEČEK –<br />

PIEKERT – ORAVCOVÁ 1971, p. 1.) The steel construction is walled-in.<br />

24 Other historians, such as Dr. Štefan Holčík, opine that this remnant<br />

was the smaller tower with “commandants” balcony.<br />

25 [SUPSOP] Vyjadrenie k vykonávaciemu projektu na prístavbu<br />

a rekonštrukciu budovy SNG v Bratislave. 21 November 1969,<br />

typewritten, 2 p. (cited in Note 14).<br />

33

The ceiling is of waved metal plates, and the stairway is of steel<br />

faced with marble.<br />

The construction has a gravel foundation; the ground water<br />

level was lowered using two wells.<br />

Otokar Pečený of Mostáreň Brezno designed the structural<br />

engineering of all the above-ground, i.e. steel construction;<br />

based on this contract, he became an employee of Dedeček’s<br />

studio X. Ateliér, and took the main role in designing construction<br />

of Dedeček’s later steel structures, especially the culture/sports<br />

hall in Ostrava. He also designed the structure of the depository<br />

racks/shelving (“depository coulisse of steel construction” DEDEČEK 1968, p. 2),<br />

again manufactured by Mostáreň Brezno.<br />

The load-bearing system of the bridging is in four girders on two<br />

30 cm-wide abutments at a distance of 54.5 m. One of these<br />

is fixed, the other socketed, allowing tensibility of the construction.<br />

The lowest of the three cascading levels in the bridging is<br />

suspended on bottom bands of the lowest-situated girders. The<br />

upper two levels are placed on the upper bands of the girders.<br />

Thus the main construction combines support and suspension.<br />

The roofing, including the glassed ceilings, is supported by<br />

crossbeam on the upper bands of the upper girder (toward the<br />

river) and of the lowest girder (toward the courtyard). This means<br />

the individual levels are each supported by a <strong>single</strong> girder, with<br />

the other securing stability in case of unbalanced loading.<br />

The bridging’s floors are of ribbed metal plates 6 mm thick,<br />

reinforced on top with braces poured over with a 6 cm layer<br />

of concrete. This created solid flat elements, able to take both<br />

perpendicular loading and the entire horizontal force in a lateral<br />

system of abutments, while stabilizing the pressed bands of the<br />

girders. Auxiliary stairways and an elevator are situated to the<br />

sides of the abutment.<br />

The topmost girder has a cornice (console) on both sides. To<br />

the east, toward the former Dom Československo- sovietskeho<br />

priatel’stva (now Esterházy palace of the SNG), the girder is<br />

34

corniced at about 11 m (11.06 m), and to the west, toward<br />

Belluš’ Hotel Devín it is laid at about 8 m (7.6 m). The load<br />

of the framed walls – the levels’ supporting elements – is on<br />

both of the corniced ends (DEDEČEK undated, pp. 5–6). In addition to<br />

the corniced construction, there are further auxiliary constructions<br />

(towers) at the sections at the edge. The total length of the<br />

bridging construction is therefore 73.5 m.<br />

The steel bridge thus designed can carry the three floors –<br />

terraced walkways (receding upwards by more than half of the<br />

floor plan surface) with a view of the entire height of exhibition<br />

space toward the roof daylight from the north. White artificial<br />

lighting using halogen bulbs is built into the ceiling of each<br />

walkway/terrace. Artworks can be installed flexibly in the open<br />

three-level longitudinal, thanks to a system of partitions tracked<br />

on the ceiling and floor of all three levels. Movable partitions are<br />

stackable by the bridging’s western side wall.<br />

The space, tall and rising, white and cascading, is 54.5 m long,<br />

with diffuse top daylight as supplemented with artificial halogen<br />

lighting. It was designed mainly for installation and viewing of modern<br />

art works. An unrealized gallery of temporary exhibitions, over<br />

the main entry by Hotel Devín, was intended to serve contemporary<br />

art. In the variable space of the segmentable “white cascading<br />

prism”, modern pieces can be installed without frames and<br />

pedestals, in cycles or other accumulations, such that the space<br />

becomes their continuation. It does not create unchangeable spatial<br />

fields, whether hierarchized or not. (Presently in renovation).<br />

In addition to the exhibition spaces in the bridging, and the<br />

small depositories in the historical building’s garret, the main<br />

depository spaces were situated underground for space management<br />

– there are two storeys of depositories under the<br />

administrative wing, and one under the bridging; diaphragm<br />

walls protect against ground water leakage (anchored by steel<br />

cables in the ground along the external perimeter), using sealed<br />

internal surfaces. 26<br />

26 Waterproof expanding mortar Waterplug with cement-based Thoroseal.<br />

35

The architect’s second alternative for the southern wing anticipated<br />

cladding, for the administrative and bridging structures,<br />

of white and red glass mosaic tile (from the firm Jablonecká<br />

bižutéria: white no. 937 and red no. 1561) and facing of slate<br />

(from Moravské ště rkovny and pískovny Olomouc); for the third<br />

alternative, he designed an alternative facing of anodized steel<br />

from Hunter Douglas (with “golden”, or more precisely bronze,<br />

finishing). However for reasons of time and finances the cladding<br />

was realized in the winter using “dry assembly” of siporex<br />

panels, quickly finished with profiled enameled aluminium plates<br />

(with white and red enamel). The bridging’s abutments and the<br />

administration’s parterre are faced with gray-black slate (the design<br />

featured facing the abutments at ground level with black<br />

marble; not realized).<br />

Thus the architect had to adjust to rapid “winter assembly” of<br />

the facades and their surfaces, so the first stage of construction<br />

(the Danube gallery wing) could be put into use on the occasion<br />

of the 29th anniversary of The 1948 Czechoslovak coup d’état<br />

and the 29th anniversary of the SNG’s founding. This is why<br />

he chose the “temporary” installation of a metal facing, in part<br />

because the material corresponded to the architectural character<br />

of the building’s facing wing: “It may seem too unusual to<br />

use such surfacing material, but they are the expression of the<br />

current material and technological circumstances, and reflect<br />

the current progress and condition of industrial manufacturing.<br />

So there is no reason they ought not to become significant<br />

media for modern architecture. This is especially so if it is architecture<br />

that in no way reminds us of preceding developmental<br />

phases of architecture in our country. Interiors, too, use equally<br />

new materials 27 .” (DEDEČEK undated [1975], p. 7)<br />

The indoor white cement masonry was designed to have<br />

a surface layer of crushed white marble (supplied by Umelecké<br />

remeslá; not realized). The atypical glass windows, doors and<br />

walls were supplied by the state-run Sklounion Teplice, ZUKOV<br />

in Prague and the collective Umeleckých remesiel.<br />

36

The atypical portions of the interior, in particular the raised auditorium<br />

seating of light wood, the profiled acoustic wall cladding<br />

and the paned wooden acoustic ceiling, with the cinema hall<br />

lighting and sound system, was realized according to the design<br />

of Jaroslav Nemec. He also designed the built-in wooden<br />

office furniture (with built-in cabinet configuration including sink<br />

and closet space). He designed low seating for the exhibit hall<br />

(square upholstered, with out armrests covered in black leather,<br />

on metal legs and a solid square base) and square wooden tables<br />

with laminated surface on an analogous metal base (the collective<br />

Umeleckých remesiel also participated in making this furniture).<br />

Nemec’s design for the secretariat interior, meeting rooms,<br />

offices and director’s suite underwent major changes. For the<br />

offices and director’s suite he designed atypical white wood<br />

wall covering in columns, with white console desks in various<br />

orthogonal shapes, dimensions and heights, which with the<br />

white surfacing and lighting panels made for a “<strong>single</strong> whole,<br />

in construction and architecture”, accented with black and light<br />

wood surfaces; it was a customized, partly “built-in interior” for<br />

the 1960s, modified in the late 1970s, and it went unrealized.<br />

Also unrealized was his customized “diagram table” (NEMEC 1978,<br />

p. 3). The spaces were furnished with atypical office furniture of<br />

light wood, and manufactured seating from the ALFA series, by<br />

the state firm Turčan in Martin.<br />

Classification<br />

Form/style : A short review by Jozef Liščák did not categorize<br />

the building in style or form. The review concerned itself roughly<br />

equally with stages I and II of the construction as well as the<br />

27 The architect was mainly referring to panelling (Izomín),<br />

sprayed-on surfacing (Dikoplast) and floor surfaces (Izofloor),<br />

in support of the stone flooring of public gallery spaces.<br />

IZOMÍN came from the IZOMAT plant in Nová Baňa; these are<br />

hard insulation panels of mineral fibre with strong fireproofing<br />

resistance. The Swedish firm Junkers supplied the technology;<br />

they started producing in Slovakia in 1973.<br />

37

unbuilt stages III and IV. The (future) SNG renovation and<br />

addition was regarded as a <strong>single</strong> whole. He even regarded<br />

the facade facing as provisional, and stressed the stone cover<br />

design of the facing wing and the administrative building:<br />

“The colouring of the temporary metal outside cladding is problematic...<br />

The final facade treatment – a stone facing with a cultivated<br />

structure and colouring anticipated – will favourably<br />

round out the architectural aspect of the SNG complex. It will<br />

unify and underline the rich architectural plasticity, with maximum<br />

effectuation of monumentality.” (LIŠČÁK 1981, pp. 4–5.)<br />

Another reviewer was the new gallery director Štefan Mruškovič<br />

(serving 1975–1990; Dr. Karol Vaculík was not allowed to<br />

remain in his position even for the opening of the structure he had<br />

worked so vitally to bring about). In his mid-1970s review, this<br />

successor to Vaculík recounted critical voices from among gallery<br />

visitors and employees: criticism ranging from how the historical<br />

barracks building was supplemented, through the construction’s<br />

architectural resolution and the bridging’s outdoor appearance,<br />

even to the atrium’s plinth, the incongruity of the building’s indoor<br />

entry spaces (small), and the inconvenience (undersized) of the<br />

stairways, along with the construction’s technical shortcomings.<br />

Similarly to Liščák, Mruškovič noted that this was just a fragment<br />

of the whole solution, a recapitulation phase in Dedeček’s<br />

design; he did not note the contributions of individuals to decision-making<br />

(he nowhere mentioned Dr. Vaculík) or the changes<br />

forced onto the project. Finally he concluded: “Our experience<br />

has shown that the opinions and impressions of everyday SNG<br />

visitors often differ quite diametrically. The critical voices that at<br />

first absolutely rejected the addition’s solution and its surfacing<br />

are no longer so strong, now that the SNG has been built and<br />

opened..., although much of the public still has not accepted the<br />

building’s most basic construction and architecture... But there<br />

are also some who praise the uniqueness of the building’s modernity<br />

and construction...” As the incoming director, he valued<br />

the ability to install artworks in the “free” halls, and in a cascaded<br />

space with diffuse lighting (MRUŠKOVIČ 1981, pp. 6–7).<br />

38

In 1982, in an article summarizing the state of Slovakia’s architecture,<br />

Dr. Martin Kusý publically addressed the discussion on<br />

the SNG: “The stump of the Slovak National Gallery in Bratislava<br />

that was realized on the riverbank was, without regard<br />

to how much was known of the overall aim, quite sharply condemned.<br />

Few would then allow that the solution of the exhibition<br />

spaces was optimal, with excellent technical parameters<br />

and a smooth connection to the old building, which is entirely<br />

visible from the riverbank. The artistic comprehension that<br />

irritates the public is focused on the large coloured surfaces<br />

that modulate to the scale and vital pulsing betokened by the<br />

neighbouring bridge and the heavy traffic. Most importantly,<br />

it is still to be completed.” (KUSÝ 1982 /?/, p.?) The same year,<br />

Tibor Zalčík and Matúš Dulla included the building in the book<br />

Slovenská architektúra 1976–1980, in the “Massiveness of<br />

form and shape” chapter, with more recent reviews and historiography<br />

on the gallery, mainly in connection with the discussion<br />

on the monumental in modern and/or socialistic architecture.<br />

In 2001, Imro Vaško attempted to emancipate the SNG site<br />

from locally ensconced classifications, citing Breuer’s Whitney<br />

Museum in New York and putting the SNG in its own class of<br />

“sculpturalism”: “The aggressive expression in both of these<br />

architectures is no accident, it corresponds to the sculptural<br />

tendencies of the sixties. There is no question of the period’s<br />

brutality here, as both buildings work with, there is no recognition<br />

of the construction materials of [Le] Corbusier and [Paul]<br />

Rudolph’s handling of architectural concrete.” 28<br />

Foreign architects and reviewers joined the discussion on<br />

the character of the SNG bridging only in the new century<br />

and millennium. The Austrian reviewer M. Hötzl – as cited in<br />

the thesis by Tatiana Krasňanská – refers to the coarse, raw<br />

( brachial) quality of the bridging as left-over from the modern:<br />

28 VAŠKO, Imro. Paralely. New Ends alebo Čo nového<br />

v New Yorských chrámoch umenia... a na Slovensku<br />

(Boom galerijného Disneylandu). Projekt. Revue slovenskej<br />

architektúry, 43, 2001, vol. 2, p. 25.<br />

39

“Doch gerade durch diese brachiale Verkleidung wirkt die<br />

große Struktur und stellt ein Meisterwerk dar, das längst<br />

über die Moderne hinausgewachsen ist.” / “And by this very<br />

instrumentality of this brachial encasement, the large structure<br />

impresses, and represents a masterpiece that has far outgrown<br />

the modern”. 29<br />

In 20<strong>05</strong> the Dutch architect Willem Jan Neutellings,<br />

together with members of the Academy of Fine Arts architecture<br />

department, symbolically founded the Slovak Institute<br />

for the Preservation of Communist Monumental Architecture<br />

Heritage. Dedeček’s completion of the SNG site is one<br />

of three initial pieces he includes. He thereby symbolically<br />

places this construction in the context of European communist<br />

monumental architecture.<br />

Sign/Symbolic : Any place the gallery’s Danube is discussed<br />

as bridging or a bridge, it is being treated as an ostensible indication<br />

of a bridge, or a bridge/building, and simultaneously as<br />

an elementary sign (based on the external similarities to bridge<br />

structure, and on the causal link of the structure with building<br />

form). Indeed “bridging” is a technical term, which has come to<br />

stand for the whole gallery site and expresses one of its main<br />

architectural themes.<br />

The current gallery director Alexandra Kusá gave an interview<br />

in association with “various symbols” with a visitor (with a cameraman<br />

of a film about the gallery) who still sees the SNG bridging,<br />

now temporarily painted gray, as a “red monstrosity”. 30 This “red<br />

monstrosity” stands for the bridging because of the period’s<br />

ideas of something huge, amorphous and frightful, which might<br />

serve as an allegorical epithet for the regime with no human face.<br />

After the bridging was put into use, the side surfaces (“crosscut<br />

edges”) were red with an “indented” bevelled facade (to be<br />

precise, the lower edges of the indentation, as seen from below).<br />