Italian Inlaid Marble Tabletop

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

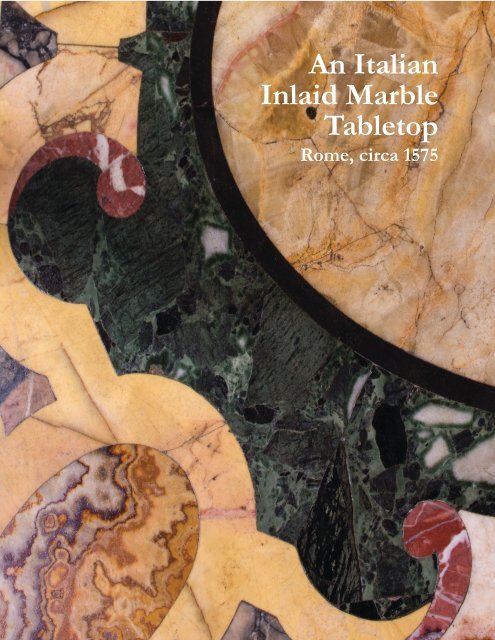

An <strong>Italian</strong><br />

<strong>Inlaid</strong> <strong>Marble</strong><br />

<strong>Tabletop</strong><br />

Rome, circa 1575

A later 16th century, <strong>Italian</strong><br />

commesso tabletop, with<br />

geometric border framing<br />

strapwork, including four ovals<br />

in antique alabastro fiorito. The<br />

large, central oval is in antique<br />

Egyptian alabaster.

An <strong>Italian</strong> <strong>Inlaid</strong> <strong>Marble</strong> <strong>Tabletop</strong><br />

Rome, circa 1575<br />

In Rome, by the middle of the 16th century, the predominant style of<br />

decorative inlaid stonework – opus sectile (cut stone) – employed across<br />

one and a half millenia, since the time of Augustus, was in need of some<br />

refreshing. Beginning about 1550 “a new manner emerged, influenced<br />

by ancient examples and marked by a wider and more colorful range of<br />

marbles, in arrangements still predominantly geometric but now usually<br />

incorporating scrolls, cartouches, peltate forms, multiple borders, and<br />

oval rather than circular centres, regularly of richly figured alabasters”,<br />

from Roman Splendour, English Arcadia; Jervis and Dodd.<br />

Interestingly, while this method was applied to wall surfaces, floors,<br />

and some decorative arts, a predominant use, and the most creative,<br />

was with impressive tabletops, always undertaken for the most<br />

wealthy, discerning clients, including a range of royalty, church figures,<br />

various Medicis, and others. Why were these marble inlaid tables so<br />

popular with this crowd? These objects were among the most visually<br />

ostentatious a Duke, Cardinal, merchant or political figure might<br />

possess – relatively large, very skillfully and intricately crafted, fashioned<br />

in the richest palette of stones. These stones, including many of the<br />

rarest colors and patterns, were gathered from the ruins of ancient<br />

Rome, where they had been brought, a milennia and a half before, from<br />

the far reaches of the empire. These tables include stones originally<br />

quarried in Greece, Egypt, Tunisia, as well as present day Italy. In the<br />

16th century (and later), ownership of commesso tables brought with it<br />

an explicit connection to Imperial Rome at the zenith of its power.<br />

While the phenomenon of this type of stone inlay craft began in Rome,<br />

by the beginning of the 17th century, many of its artisans were equally<br />

at home in Florence; and there was a good deal of traffic in materials,<br />

products, and artisans between the two cities. Those fashioning<br />

ultra-opulent tabletops were not the quaint craftsmen we might imagine<br />

today. Among the earliest was Jean Menard (1525 – 1582), described<br />

as a “franciosetto” – little Frenchman. History records that in 1568 he<br />

was involved in a knife fight at the Florentine home of his acquaintance,<br />

Michelangelo.<br />

Opposite - Detail, later 17th century <strong>Italian</strong> commesso tabletop.

Soon enough, Florence developed its own variation of this decorative<br />

craft, employing figural decoration – plants, trophies, etc. –<br />

supplementing the more rigorously geometric design characteristic of<br />

Roman work.<br />

The design of the table described here adheres to that earlier, Roman<br />

approach. And yet, as we shall see, it is closely related to another,<br />

almost certainly later, inlaid marble top which also exhibits Florentine<br />

characteristics.<br />

Our table is 58.625” x 44.5”. It includes a marble edge similar to<br />

portoro, but which may be giallo e nero antico, a not quite identical<br />

stone whose quarrying began earlier. Inside this is a band of repeating<br />

geometric ornament in a variety of stones including carrara, bianco<br />

e nero antico, at least three different types of brecciated marbles –<br />

traccagnini, corallina, and possibly diaspro tenero di Sicilia - as well as<br />

alabasters, including pecorella.<br />

This repeating ornament frames a large rectangle, featuring curvilinear<br />

“strapwork” in giallo antico with accents in rosso antico, alabastro fiorito,<br />

and a white stone with diffuse red veining which is, so far, unidentified.<br />

The strapwork outlines sections of africano marble, and four ovals in<br />

alabastro fiorito, and surrounds a field of verde antico, which further<br />

frames a thin oval band of nero antico. Inside this is the table’s<br />

center-piece, a semi-transparent/translucent oval of antique Egyptian<br />

alabaster, perhaps alabastro cotognini.<br />

The underside of the table is a single stone slab of peperino, running to<br />

the edge of the molded band of giallo e nero antico. This slab, though<br />

antique, may postdate the marble inlay work.<br />

The effect, of course is very, very grand.<br />

Provocatively, our table is remarkably similar to one now in Florence’s<br />

Villa del Poggio Imperiale, and before that, in the city’s Palazzo Pitti,<br />

both places with intimate connections to Ferdinando de Medici.<br />

Opposite above - Similar tabltetop currently in the Villa del Poggio Imperiale,<br />

Florence.<br />

Opposite below - Similar tabletop, on a later base, in Il Perestilio, Villa del<br />

Poggio Imperiale

In the late 16th and early 17th centuries, Ferdinando I’s attention was<br />

seized by this new style of stone inlay-work, and especially by these<br />

types of tables. He commissioned several and owned others. In 1588, he<br />

founded Florence’s Opificio delle Pietre Dure (workshop of hardstones)<br />

for the purpose of producing this type of decorative work for important<br />

projects, and training skilled artisans. Originally opened in the city’s<br />

Casino Mediceo, the workshop later moved to the Uffizi gallery.<br />

The Poggio Imperiale table, illustrated in Annamerie Guisti’s La<br />

Marquetrie de Pieres Dures, is very slightly smaller – 54.375” x 41”. Its<br />

decorative scheme, though, is identical, with a perimeter molded edge;<br />

repeating geometric border, framing a rectangular panel divided by<br />

strapwork; and featuring, at its center, a large oval of rare alabaster. Its<br />

materials differ somewhat and, most significantly, its strapwork frames<br />

various figural motives, including flowers and vegetal forms, as well as<br />

musical and military tropies.<br />

The differences between the two tables roughly correspond, of course, to<br />

the differences between Roman and Florentine work in this period.<br />

It has been suggested that the table described here predates that at the<br />

Poggio Imperiale, whose date is given as late 16th/early 17th century.<br />

This might point in the direction of our table dating to c. 1575, or so.<br />

Our ongoing research efforts to determine the designer, maker,<br />

commissioner, and original owner of this table have not yet borne fruit.<br />

However, with the close similarities of the Poggio Imperiale and our<br />

tables, and reasonable surmises regarding their dates, it seems likely<br />

that ours was, in some way, preparatory to that at Poggio Imperiale.<br />

Additionally given that table’s history of being shuttled between the<br />

Villa and Palazzo Pitti, both renovated nearly simultaneously by<br />

Ferdinand I, and his keen interest in this form of marble inlay work,<br />

it would be surprising if the table described here was not associated in<br />

some way with this Grand Duke of Tuscany.<br />

For more about 16th and early 17th century <strong>Italian</strong> inlaid marble<br />

tabletops, please see sales linked to here, here, here, and here.<br />

Opposite - Detail, later 17th century <strong>Italian</strong> commesso tabletop.