Dows Dunham Recollections of an Egyptologist

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

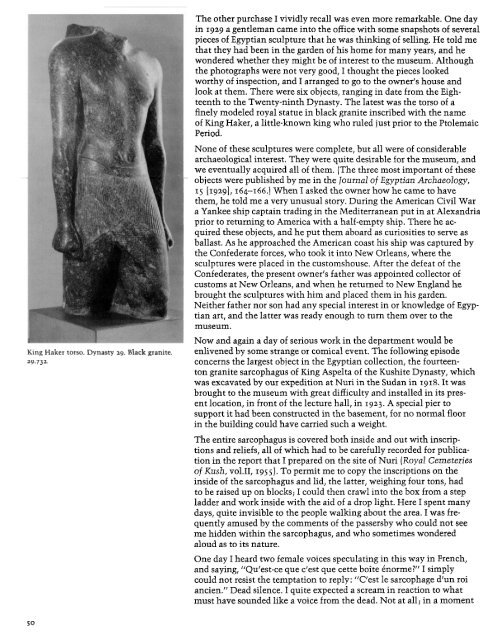

King Haker torso. Dynasty 29. Black gr<strong>an</strong>ite.<br />

29.732.<br />

The other purchase I vividly recall was even more remarkable. One day<br />

in 1929 a gentlem<strong>an</strong> came into the <strong>of</strong>fice with some snapshots <strong>of</strong> several<br />

pieces <strong>of</strong> Egypti<strong>an</strong> sculpture that he was thinking <strong>of</strong> selling. He told me<br />

that they had been in the garden <strong>of</strong> his home for m<strong>an</strong>y years, <strong>an</strong>d he<br />

wondered whether they might be <strong>of</strong> interest to the museum. Although<br />

the photographs were not very good, I thought the pieces looked<br />

worthy <strong>of</strong> inspection, <strong>an</strong>d I arr<strong>an</strong>ged to go to the owner’s house <strong>an</strong>d<br />

look at them. There were six objects, r<strong>an</strong>ging in date from the Eighteenth<br />

to the Twenty-ninth Dynasty. The latest was the torso <strong>of</strong> a<br />

finely modeled royal statue in black gr<strong>an</strong>ite inscribed with the name<br />

<strong>of</strong> King Haker, a little-known king who ruled just prior to the Ptolemaic<br />

Period.<br />

None <strong>of</strong> these sculptures were complete, but all were <strong>of</strong> considerable<br />

archaeological interest. They were quite desirable for the museum, <strong>an</strong>d<br />

we eventually acquired all <strong>of</strong> them. (The three most import<strong>an</strong>t <strong>of</strong> these<br />

objects were published by me in the journal <strong>of</strong> Egypti<strong>an</strong> Archaeology,<br />

15 [1929], 164-166.) When I asked the owner how he came to have<br />

them, he told me a very unusual story. During the Americ<strong>an</strong> Civil War<br />

a Y<strong>an</strong>kee ship captain trading in the Mediterr<strong>an</strong>e<strong>an</strong> put in at Alex<strong>an</strong>dria<br />

prior to returning to America with a half-empty ship. There he acquired<br />

these objects, <strong>an</strong>d he put them aboard as curiosities to serve as<br />

ballast. As he approached the Americ<strong>an</strong> coast his ship was captured by<br />

the Confederate forces, who took it into New Orle<strong>an</strong>s, where the<br />

sculptures were placed in the customshouse. After the defeat <strong>of</strong> the<br />

Confederates, the present owner’s father was appointed collector <strong>of</strong><br />

customs at New Orle<strong>an</strong>s, <strong>an</strong>d when he returned to New Engl<strong>an</strong>d he<br />

brought the sculptures with him <strong>an</strong>d placed them in his garden.<br />

Neither father nor son had <strong>an</strong>y special interest in or knowledge <strong>of</strong> Egypti<strong>an</strong><br />

art, <strong>an</strong>d the latter was ready enough to turn them over to the<br />

museum.<br />

Now <strong>an</strong>d again a day <strong>of</strong> serious work in the department would be<br />

enlivened by some str<strong>an</strong>ge or comical event. The following episode<br />

concerns the largest object in the Egypti<strong>an</strong> collection, the fourteenton<br />

gr<strong>an</strong>ite sarcophagus <strong>of</strong> King Aspelta <strong>of</strong> the Kushite Dynasty, which<br />

was excavated by our expedition at Nuri in the Sud<strong>an</strong> in 1918. It was<br />

brought to the museum with great difficulty <strong>an</strong>d installed in its present<br />

location, in front <strong>of</strong> the lecture hall, in 1923. A special pier to<br />

support it had been constructed in the basement, for no normal floor<br />

in the building could have carried such a weight.<br />

The entire sarcophagus is covered both inside <strong>an</strong>d out with inscriptions<br />

<strong>an</strong>d reliefs, all <strong>of</strong> which had to be carefully recorded for publication<br />

in the report that I prepared on the site <strong>of</strong> Nuri (Royal Cemeteries<br />

<strong>of</strong> Kush, vol. II, 1955). To permit me to copy the inscriptions on the<br />

inside <strong>of</strong> the sarcophagus <strong>an</strong>d lid, the latter, weighing four tons, had<br />

to be raised up on blocksj I could then crawl into the box from a step<br />

ladder <strong>an</strong>d work inside with the aid <strong>of</strong> a drop light. Here I spent m<strong>an</strong>y<br />

days, quite invisible to the people walking about the area. I was frequently<br />

amused by the comments <strong>of</strong> the passersby who could not see<br />

me hidden within the sarcophagus, <strong>an</strong>d who sometimes wondered<br />

aloud as to its nature.<br />

One day I heard two female voices speculating in this way in French,<br />

<strong>an</strong>d saying, “Qu’est-ce que c’est que cette boite Cnorme?” I simply<br />

could not resist the temptation to reply: “C’est le sarcophage d’un roi<br />

<strong>an</strong>cien.” Dead silence. I quite expected a scream in reaction to what<br />

must have sounded like a voice from the dead. Not at all; in a moment<br />

50