The Island Sehel - An Epigraphic Hotspot

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Island</strong> of <strong>Sehel</strong> - <strong>An</strong> <strong>Epigraphic</strong> <strong>Hotspot</strong><br />

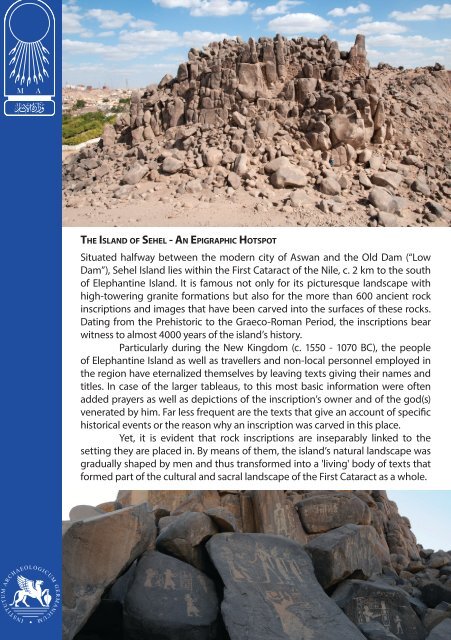

Situated halfway between the modern city of Aswan and the Old Dam (“Low<br />

Dam”), <strong>Sehel</strong> <strong>Island</strong> lies within the First Cataract of the Nile, c. 2 km to the south<br />

of Elephantine <strong>Island</strong>. It is famous not only for its picturesque landscape with<br />

high-towering granite formations but also for the more than 600 ancient rock<br />

inscriptions and images that have been carved into the surfaces of these rocks.<br />

Dating from the Prehistoric to the Graeco-Roman Period, the inscriptions bear<br />

witness to almost 4000 years of the island’s history.<br />

Particularly during the New Kingdom (c. 1550 - 1070 BC), the people<br />

of Elephantine <strong>Island</strong> as well as travellers and non-local personnel employed in<br />

the region have eternalized themselves by leaving texts giving their names and<br />

titles. In case of the larger tableaus, to this most basic information were often<br />

added prayers as well as depictions of the inscription’s owner and of the god(s)<br />

venerated by him. Far less frequent are the texts that give an account of specific<br />

historical events or the reason why an inscription was carved in this place.<br />

Yet, it is evident that rock inscriptions are inseparably linked to the<br />

setting they are placed in. By means of them, the island’s natural landscape was<br />

gradually shaped by men and thus transformed into a 'living' body of texts that<br />

formed part of the cultural and sacral landscape of the First Cataract as a whole.

<strong>The</strong> Rocks of <strong>Sehel</strong> <strong>Island</strong> - Telling Witnesses to the History of the First Cataract<br />

Located on top of an intrusive granite-granodiorite pluton, the area of Aswan is<br />

characterized by large outcrops of igneous rocks such as pink granite, which are exposed<br />

along the Nile and form its First Cataract. Especially during the pharaonic era, the surfaces<br />

of these rocks were widely used for carving inscriptions and images. Thousands of these<br />

inscriptions can still be found throughout the city area and today represent an important<br />

and unique part of Aswan’s cultural heritage.<br />

Besides the specific geographical conditions, epigraphic usage of the landscape<br />

was also stimulated by the continuous strategic role as well as the economic, political and<br />

social importance of the First Cataract. For since the beginning of its colonization more<br />

than 5000 years ago, the region has always been a border area with mixed population,<br />

an important military base, a place of extensive granite and diorite quarries and a rich<br />

centre of trade between Egypt and Sub-Saharan Africa. That is why there has always been<br />

a continual coming and going of state officials, military personnel and (since the New<br />

Kingdom) priests, who belonged mainly to the administration of the great <strong>The</strong>ban temples<br />

and were sent to supervise the clergy of the provincial sanctuaries.<br />

Especially these non-local people often took the opportunity to leave a visual<br />

mark at prominent sites they had worked at, or they had visited, in order to participate in<br />

cult activities. For this reason it is fundamental to firstly study the titles mentioned in the<br />

texts and to determine the social composition of the persons represented. Secondly, one<br />

has to link this set of people and their memorial inscriptions to the topographical setting.<br />

By this means, in many cases the ancient landscape and its functional aspects can be<br />

reconstructed, and the question why a certain place was chosen can be answered.<br />

<strong>The</strong> by far largest group of rock inscriptions can be found in the southern part of<br />

<strong>Sehel</strong> <strong>Island</strong>. A close look at the profession and social status of the people eternalized here as<br />

well as the content of the texts reveals that the island had once been an important religious<br />

site within the First Cataract region. Most of the inscriptions are connected to the cult of<br />

the goddess <strong>An</strong>uket, the so-called lady of <strong>Sehel</strong>. <strong>The</strong> large tableaus, in particular, frequently<br />

show the inscription’s owner while venerating <strong>An</strong>uket, and she is also the one most often<br />

invoked in the prayers. From other sources it is known, that a sanctuary of <strong>An</strong>uket was<br />

situated on <strong>Sehel</strong> <strong>Island</strong>, and that her annual feast centered on a river procession, in which<br />

a cult image of the goddess travelled from Elephantine to <strong>Sehel</strong> and back. It was believed<br />

that by placing a rock inscription near the ritual place or the processional path one could<br />

participate eternally in this major local cult and its public festival(s).<br />

Scholars on <strong>Sehel</strong> <strong>Island</strong> - 200 Years of Studying the <strong>Island</strong>’s History<br />

<strong>The</strong> island of <strong>Sehel</strong> and its vast amount of rock inscriptions aroused scholarly interest as<br />

early as the beginning of the 19th century. Among the first European travellers visiting the<br />

First Cataract region was the British adventurer William John Bankes (1786-1855), whose<br />

folio of notes and drawings give an account of local monuments and other archaeological<br />

remnants, that are today largely destroyed or damaged. <strong>The</strong> first scientific studies in the<br />

area of Aswan were conducted by the Royal Prussian Expedition to Egypt and Sudan<br />

(1842-1845), led by Carl Richard Lepsius. <strong>The</strong> expedition’s team, which included scholars,<br />

geographers, architects and surveyors (e.g. Georg Gustav Erbkam; see an entry of his diary<br />

cited below), as well as artists, also copied some of the most prominent monumental<br />

inscriptions. This was followed by a series of epigraphic ventures carried out by Auguste<br />

Mariette (1867), Heinrich Brugsch (1884), and Jacques De Morgan (1893), who, with the help<br />

of his colleagues, recorded and published 230 of the island’s texts.<br />

In the 20th century, Labib Habachi (1906-1994) devoted a great deal of his time<br />

and research to the rock inscriptions of the Aswan area and, thereby, gained many in-depth<br />

insights into the meaning and significance of the epigraphic heritage of the First Cataract<br />

region. However, while revising the copies made by De Morgan and others, it became<br />

evident that the hitherto existing catalogue needed to be replaced by a new one that also<br />

incorporated new discoveries. Eventually, a large volume, covering more than 550 texts<br />

displayed on the rocks of <strong>Sehel</strong>, was released in 2007 by <strong>An</strong>nie Gasse and Vincent Rondot.<br />

Even after almost 200 years, research on the island’s history and the textual<br />

tradition of its inscriptions is still not completed and will require further investigation.<br />

Sunday 29th Sept(ember) 1844<br />

“My birthday and departure from Philae. [...]<br />

As for the continuation of our journey, navigating through the rapids and past the shallows called for<br />

our utmost attention [...]; We were on top of the boat’s roof watching the spectacle with keen interest,<br />

and gazed at the changing landscapes, while passing along the desert on the west bank and a great<br />

variety of towering rock islands. Later, we disembarked on the beautiful island of <strong>Sehel</strong>e, opposite<br />

another island called Senarti. On the former, we found the remains of ancient monuments and,<br />

covered in potsherds, large outcrops of rock featuring a multitude of stelae, which were 'exploited' by<br />

(Carl Richard) Lepsius and Max (Weidenbach); [...]”<br />

Georg Gustav Erbkam, Tagebuch meiner aegyptischen Reise (Diary of my Egyptian Journey)

How to explore the Rocks of <strong>Sehel</strong><br />

A Guide to the Pharaonic Rock Inscriptions and Archaeological Remains on the <strong>Island</strong><br />

01 Large Tableau belonging to the viceroy of Kush, Huy. During the New Kingdom,<br />

Kush was an Egyptian province in Lower Nubia that was governed by a viceroy, who<br />

was appointed by the Egyptian king. Huy, who lived in the 19th Dynasty and served<br />

under king Ramesses II (1279-1213 BCE), is shown in the lower part of the relief, his<br />

hands uplifted in adoration. In the upper part, his master, Ramesses II, offers wine<br />

to the local gods Khnum, Satet and <strong>An</strong>uket, who form the Triad of Elephantine. <strong>The</strong><br />

text underneath his elbow reads: “Giving wine to his father (i.e. Khnum)”.<br />

02 Most inscriptions’ owners have themselves depicted with insignia of office<br />

and rank. In this case, Payamen, with shaven head and short apron, carries an armshaped<br />

censer, in which he is burning incense grains in front of the cartouche of<br />

Amenophis II (18th Dynasty, 1428-1397 BCE). His handling of the ritual instrument<br />

as well as his dress both illustrate the titles of Payamen mentioned in the accompanying<br />

text. He was an 'offerer of Amun', 'scribe of the god’s offering' and 'bearer of<br />

the arm-shaped censer of this perfect god', all of which are priestly titles.<br />

01<br />

02<br />

05<br />

03<br />

06<br />

04<br />

03 <strong>An</strong>uket was the most revered goddess and the main recipient of the cult on<br />

<strong>Sehel</strong>. Hence, she is often depicted and appealed to in the local rock inscriptions.<br />

But only rarely is the adoration of a statue of <strong>An</strong>uket shown - e.g. in the tableau of<br />

the 'chief portrait sculptor in the Temple of Ra', Amenemipet (New Kingdom, 19th<br />

Dynasty). Here, the sculptor, who himself was responsible for the carving of temple<br />

statues, is adoring a statue of the island’s goddess, which is placed on a pedestal<br />

and holding a papyrus scepter (wadj-sign) as well as a symbol of life (ankh-sign).<br />

04 Unlike Amenemipet (03), who was probably from <strong>The</strong>bes and just inspecting<br />

the quarries of Aswan, Khnumemwesekhet was mayor of Elephantine and, thus, belonged<br />

to the administrative elite of the region. He and his wife Hener, a chant-euse<br />

of Khnum, the lord of Elephantine, are shown worshipping a seated statue of<br />

<strong>An</strong>uket. Furthermore, the inscription attests to the ancient practice of damnatio<br />

memoriae, i.e. the erasure of the name and the symbolic damaging of the face and<br />

hands of a person who has fallen from grace and should not be remembered.<br />

05 Throughout antiquity, Aswan was famous for its extensive red granite quarries,<br />

where many of Egypt’s great monuments such as obelisks were cut. In this context,<br />

a great number of officials who supervised works in the quarries commemorated<br />

themselves in rock inscriptions. One of them, Amenhotep, not only held the title<br />

of 'director of works in the great house of granite' during the reign of Hatshepsut<br />

(c. 1479-1458 BCE), but also was appointed high priest of <strong>An</strong>uket. That is why, in his<br />

tableau, he is wearing a leopard’s skin, which is part of the high priest’s sacred robe.<br />

06 Besides the Triad of Elephantine (Khnum, Satet and <strong>An</strong>uket), in<br />

Bakenkhons’ inscription also Amun, 'king of the gods' and main god<br />

of the New Kingdom, as well as Ramesses VI (20th Dynasty, c. 1142-<br />

1134 BCE) are venerated. Bakenkhons is known from the so-called<br />

Turin Indictment Papyrus (“Elephantine scandal”). <strong>The</strong>re it is reported<br />

that other priests had plotted to prevent him from being promoted<br />

to the position of high priest of Khnum by manipulating the oracle’s<br />

decision. But they failed and, eventually, their scheme was exposed.<br />

07 In front of Ramesses II (19th Dynasty, 1279-1213 BCE), one of his officials, Khnumemhab,<br />

is depicted on a smaller scale in the act of adoration. While his right hand is<br />

lifted, his left holds either a scribe’s palette or a papyrus roll. <strong>The</strong> attribute refers to<br />

his profession as a 'chief archivist in the two royal treasuries', 'chief scribe in the temple<br />

of Amun', and 'overseer of sealed goods in the southern foreign lands'. Particularly<br />

the latter title links Khnumemhab to the extraction and delivery of gold from<br />

Nubia’s eastern desert, which were, at this time, under the control of Amun’s temple.<br />

09 <strong>The</strong> epigraphic usage of <strong>Sehel</strong>’s landscape started already in the Old Kingdom.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Inscriptions of that period are concentrated especially near the southern bay<br />

and, for the most part, only give the name and title of the inscription’s owner. Lacking<br />

further information, it is difficult to determine why people commemorated<br />

themselves in this place. However, it can be assumed that <strong>Sehel</strong> played an important<br />

role in the control of the border region at the First Cataract. Furthermore, it is<br />

likely that already early in the island’s history it was viewed as a religious site.<br />

10 <strong>The</strong> prominent, high-lying rock features three inscriptions from different times.<br />

In the upper part, the viceroy of Kush Sethy is shown kneeling and adoring the cartouches<br />

of king Siptah (19th Dynasty, c. 1194-1186 BCE). Beneath it, the depiction<br />

and name of another viceroy, Usersatet (temp. Amenophis II, 1428-1397 BCE), who<br />

somehow must have fallen into disgrace, are partly erased. At his feet, three small<br />

male figures of varying colours probably represent the deities Petempamentes, Petensetis<br />

and Petensenis, who were venerated on <strong>Sehel</strong> <strong>Island</strong> in the Ptolemaic era.<br />

12 In ancient times, the First Cataract was considered the gateway to Nubia and<br />

in order to travel southwards, both trade expeditions as well as military troops had<br />

to pass through it. <strong>The</strong> importance of this route is illustrated by a group of texts<br />

located along the eastern hillside of Bibi Tagug. Among them, a tableau dating from<br />

the reign of Senwosret III (c. 1872-1853 BCE) commemorates the king’s campaign<br />

against Nubia and his command to clear out a navigation channel near <strong>Sehel</strong>, that<br />

was hence named “Beautiful are the ways of Khakaure (Senwosret III) eternally”.

© German Archaeological Institute,<br />

Department Cairo, 2015<br />

Text/Layout: Linda Borrmann<br />

Print: IFAO, Cairo<br />

German Archaeological Institute,<br />

Department Cairo<br />

31, Sh. Abu el-Feda<br />

11211 Cairo - Zamalek, Egypt<br />

Phone: +20-2-2735-1460<br />

Fax: +20-2-2737-0770<br />

sekretariat.kairo@dainst.de<br />

www.dainst.org<br />

Have a Safe <strong>Sehel</strong> Experience!<br />

Please stick to the footpaths and mind your step,<br />

as the rocky paths may be slippery.<br />

Don‘t climb the steep slopes and cliffs,<br />

as they are very unstable.<br />

Please do not drop litter and help us to keep the<br />

archaeological site tidy.

08<br />

<strong>The</strong> Shrine of <strong>An</strong>uket<br />

<strong>The</strong> Lady of <strong>Sehel</strong> and her Shrine at Hussein Tagug<br />

<strong>The</strong> main goddess venerated on <strong>Sehel</strong> <strong>Island</strong> was <strong>An</strong>uket, who was also commonly called<br />

the lady of <strong>Sehel</strong>. <strong>The</strong> site of her shrine was most probably located on a narrow terrace<br />

embedded within the eastern hillside of Hussein Tagug, where a broad niche had been<br />

cut into the face of the hill’s granite. Today no visible traces of the shrine’s architecture,<br />

however humble it may have been, are left, but there is strong evidence for the existence of<br />

a prominent ancient sanctuary in this area. First and foremost, the overwhelming number<br />

of dedicatory rock inscriptions assembled opposite and around the niche (see inscription<br />

of Kaemkemet cited below) attests to its religious importance (at least from the late Middle<br />

Kingdom onwards). In addition, two relief slabs made of sandstone were found at <strong>Sehel</strong>,<br />

of which one was later sold to the Brooklyn Museum in New York (see picture below). It<br />

displays two symmetrical offering scenes, in which king Sobekhotep (13th Dynasty, c.<br />

1744-1741 BCE) presents a vase to both female deities of the Triad of Elephantine, and it<br />

once formed part either of a small shrine or an altar dedicated to <strong>An</strong>uket.<br />

<strong>The</strong> situation is thus similar to other sanctuaries in the First Cataract region. As in<br />

the case of the temple of Satet at Elephantine, it is likely that also on <strong>Sehel</strong> <strong>Island</strong> the local<br />

goddess was believed to be immanent in a conspicuous feature of the natural landscape.<br />

Apparently, specific rock formations such as niches, exceptionally shaped boulders or large<br />

potholes were often considered as sacred and, as a result, used as ritual places.<br />

<strong>The</strong> relief of Sobekhotep III<br />

(13th Dynasty, c. 1744-1741<br />

BCE) shows the king offering<br />

a vessel each to the goddess<br />

Satet (left) and to the goddess<br />

<strong>An</strong>uket (right). It probably<br />

formed part of a shrine that<br />

housed the cult image of<br />

<strong>An</strong>uket on <strong>Sehel</strong> <strong>Island</strong>.<br />

(courtesy of the<br />

Brooklyn Museum,<br />

New York)<br />

Rock Inscription of Kaemkemet (see picture above)<br />

“<strong>An</strong> offering that the king gives (to) Khnum, Satet, <strong>An</strong>uket, and the gods, the lords of Elephantine.<br />

<strong>An</strong> offering that the king gives (to) <strong>An</strong>uket, the lady of <strong>Sehel</strong>,<br />

Osiris, foremost of the west, and <strong>An</strong>ubis, who is upon his hill,<br />

so that they may give<br />

a thousand of beer and bread, a thousand of flesh and fowl, a thousand of offerings,<br />

a thousand of incense and oil, as well as a thousand of every good and pure thing<br />

to the Ka (i.e. the soul of a deceased person) of the high priest of Satet, <strong>An</strong>uket, and the gods,<br />

the lords of Ta-seti (i.e. region to the south of Egypt), Ka(em)kemet.”<br />

Column 1-5 (Praying for Offerings)<br />

New Kingdom, 20th Dynasty (c. 1186-1070)<br />

“O living ones upon the earth,<br />

every priest, every god’s-father (i.e. a priest), every lector priest, every scribe,<br />

and everyone who knows his spell who may pass by this stela:<br />

the gods of your town shall favor you, you shall be loved (by) the king of your time,<br />

and shall bequeath your office to your children after old age,<br />

if you will say:<br />

'<strong>An</strong> offering that the king gives (to) Khnum, Satet, and <strong>An</strong>uket of all good and pure things to the Ka of<br />

the high priest of Khnum, Satet, and <strong>An</strong>uket, Kaemkemet!' “<br />

Column 6-12 (Appeal to the Living)

11<br />

<strong>The</strong> Famine Stela<br />

<strong>The</strong> Famine Stela - <strong>An</strong> Extraordinary Text and its Historical Background<br />

One of the most discussed and most intriguing inscriptions carved on the rocks of <strong>Sehel</strong><br />

<strong>Island</strong> is the so-called Famine Stela. <strong>The</strong> monumental stela, measuring 180 cm x 171 cm,<br />

is featured on the face of a large free-standing granite boulder on the summit of Bibi<br />

Tagug and facing in a south-eastern direction. When it was found in 1890 by the American<br />

archaeologist Charles Wilbour, the text instantly caused some puzzlement over its dating<br />

and authorship. For though language and phrasing clearly indicate that it is a work of the<br />

Ptolemaic era (304-30 BCE), the events described are stated to have taken place in the Old<br />

Kingdom, during the reign of king Djoser (c. 2665-2645 BCE).<br />

In 32 vertical lines (columns) the inscription recounts that one year the river Nile<br />

failed to rise high enough to flood the lands and that, hereupon, Egypt was afflicted by a<br />

severe seven-year-long famine. Distraught over the hardship his people are facing, Djoser,<br />

second king of the 3rd Dynasty, writes to the 'governor of the domains of the south', Mesir,<br />

who is probably stationed at Elephantine <strong>Island</strong>. <strong>The</strong> king tells him that he has consulted<br />

a wise lector-priest in order to obtain knowledge on the source of the Nile and how to<br />

influence its actions. From him he has learned that the god Khnum of Elephantine, like a<br />

divine doorkeeper, controls the coming of the Nile flood as it enters Egypt on its southern<br />

border. Later, Khnum appears to Djoser in a dream promising him to restore the inundation<br />

and, thus, to end the famine. Relieved and deeply grateful, the king now issues a decree.<br />

<strong>The</strong>rein, he donates the region of the Dodekaschoinos (“twelve mile land”, i.e. northern<br />

part of Lower Nubia, from the First Cataract to Takompso) as well as a 10 percent share<br />

each of the revenue derived from it and from Nubian trade to the temple of Khnum on<br />

Elephantine <strong>Island</strong>. Moreover, it is ordered that the temple shall be restored and its new<br />

resources shall be used as offerings to Khnum. Accordingly, right above the text of the<br />

stela, king Djoser is depicted, while burning incense for (i.e. offering to) Khnum-Ra, Satet,<br />

and <strong>An</strong>uket, which form the Triad of Elephantine.<br />

To this day, it is still uncertain who originally composed the text of the Famine Stela,<br />

and when it was cut into the stone. Although a few scholars believe it to originate from a<br />

genuine decree of the 3rd Dynasty, the majority of Egyptologists regard the inscription’s<br />

early date as fiction. Hence, it was argued that the clergy of the temple of Khnum had<br />

been responsible for setting up the stela, because, in the Ptolemaic era, the temples of the<br />

local deities such as Khnum were eventually overshadowed by the Isis temple of Philae that<br />

was greatly enhanced at that time. Possibly the priests of Khnum – rivalling those of Isis –<br />

wanted to strengthen their position and claims with the aid of a 'pious forgery'.<br />

<strong>The</strong> Famine Stela, Column 1-4 (<strong>The</strong> King’s Lament)<br />

“I was in mourning on my throne,<br />

Those of the palace were in grief,<br />

My heart was in great affliction,<br />

Because Hapy [i.e. the deified Nile]<br />

had failed to come in time<br />

In a period of seven years. [...]<br />

Courtiers were needy, temples were shut,<br />

Shrines covered in dust,<br />

Everyone was in distress.”<br />

Column 6-9 (Source of the Nile)<br />

“<strong>The</strong>re is a town in the midst of the deep,<br />

Surrounded by Hapy, Yebu by name; [...]<br />

Khnum is the god [who rules] there,<br />

[He is enthroned above the deep],<br />

His sandals resting on the flood;<br />

He holds the door bolt in his hand,<br />

Opens the gate as he wishes.<br />

He is eternal there as Shu [i.e. god of wind and air],<br />

Bounty-giver, Lord-of-fields, so his name is called.”<br />

Columns 18-22 (Khnum’s Revelation)<br />

“I am Khnum, your maker!<br />

My arms are around you,<br />

To steady your body, to safeguard your limbs.<br />

[...] <strong>The</strong> shrine I dwell in has two lips,<br />

When I open up the well,<br />

I know Hapy hugs the field,<br />

A hug that fills each nose with life,<br />

For when hugged the field is reborn! [...]<br />

Hearts will be happier than ever before!”<br />

Columns 22-23 (<strong>The</strong> King’s Donation)<br />

“I awoke with speeding heart.<br />

Freed of fatigue I made this decree<br />

On behalf of my father Khnum.<br />

A royal offering to Khnum,<br />

Lord of the cataract region and chief of Nubia [...]”<br />

(For full translation, see M. Lichtheim,<br />

<strong>An</strong>cient Egyptian Literature, 3:94-103.)

Unveiling the Secrets of <strong>Sehel</strong> - Ongoing <strong>Epigraphic</strong> Research<br />

For almost 30 years, the German Archaeological Institute, in close co-operation with the<br />

Egyptian Ministry of <strong>An</strong>tiquities, has been working on the epigraphic heritage of the Aswan<br />

region. Since 2014, the team has also been conducting field work on <strong>Sehel</strong>. Its aims are to<br />

check and revise already published copies of texts, to survey and protect the area, as well<br />

as to detect and to document so far unknown rock inscriptions and images. Additionally,<br />

all available information about the local landscape and the ancient environment is being<br />

gathered. Thus, the scholars try to answer crucial questions regarding the different<br />

functional aspects of the island and the chronology of its usage during Pharaonic times.<br />

Amongst others, until now more than 60 dynastic rock images, mostly standing<br />

male figures lacking an inscription, were newly discovered. <strong>The</strong>se figures can be<br />

considered as self-representations of a semi-literate or illiterate personnel employed on<br />

<strong>Sehel</strong> <strong>Island</strong> from the Old Kingdom onwards and seem to be connected rather to the<br />

island’s function as an important check point within the First Cataract than to the local<br />

cult of <strong>An</strong>uket. While controlling and monitoring the border area south of Aswan, these<br />

people seem to have depicted themselves and their professional routine in the immediate<br />

vicinity of their workplace. It can be expected that further research on those depictions<br />

may shed light on various aspects such as the economic function and the evolution of<br />

the epigraphic usage of the island of <strong>Sehel</strong>, which are not yet entirely understood.<br />

How to Get to <strong>Sehel</strong> <strong>Island</strong><br />

A 20 minute motor boat or felucca trip from Aswan Harbour<br />

upstream the Nile, will get you to <strong>Sehel</strong> <strong>Island</strong>. Also, it is possible to<br />

take the local public ferry, a rowing boat, which is signed from the<br />

road south of the Aswan Stadium. At the landing place, a path leads<br />

up from the river bank to the entrance of the archaeological site<br />

with its two large hills of Hussein Tagug and Bibi Tagug, which are<br />

now enclosed by a metal fence.