You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

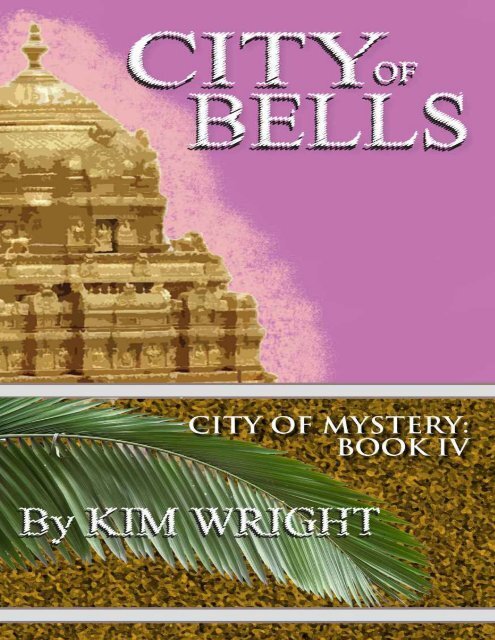

CITY OF BELLS<br />

City of Mystery, Book 4<br />

By Kim Wright

Bombay, India – Byculla Club – The Kitchen<br />

August 7, 1889<br />

3:40 PM<br />

The two bodies lay face to face on the marble slab. At first their pose had been more decorous –<br />

positioned well apart, each with straightened legs and their arms crossed over the chest, much in the<br />

manner of buried monarchs. But ice is a precious commodity in the summer, especially in India, so<br />

on the second day they had been inched more tightly together to conserve the cold, and on the third<br />

day they had been moved closer yet again, until the limbs of the man and woman eventually<br />

overlapped. Fused together in their icy dome, far more intimate in death than they had ever been in<br />

life, the elderly British woman and her loyal – but somewhat ineffectual – Indian bodyguard stared<br />

blankly into each other’s frozen eyes.<br />

The officer charged with the investigation had been trained as a military man. While he was<br />

comfortable with tribunals and inquiries of a certain nature, he was entirely out of his element here, at<br />

the Byculla Club, the most exclusive British enclave of the whole of the Bombay Presidency. He had<br />

tried not to gawk at the satin-draped manservant who had met him in the foyer and escorted him<br />

through the elegant rooms, his boots no doubt scuffing the floors with every step. Through the open<br />

doors and beyond the terrace he had caught inviting glimpses of a garden where women took tea,<br />

tennis courts which stood empty in the heat of the day, even a shimmer of light which promised the<br />

presence of a swimming pool. On the subcontinent, water was the greatest luxury of all.<br />

Yes, the Byculla had everything – except, it would seem, a mortuary, which is why any persons<br />

who had the audacity to get themselves murdered within these high gates could expect nothing more<br />

than a transfer here, to the kitchens, where they would await justice in much the same resigned manner<br />

that their friends awaited the arrival of the cheese course.<br />

The officer leaned against the marble slab, feeling the cold of it permeate through his thin linen<br />

trousers, and exhaled with a curse. He considered the haunches of meat hanging on hooks all around<br />

him, the bank of oysters heaped on a separate table, a flock of birds suspended, still feathered, from a<br />

corner. So much death in one room. He didn’t like death, a fact which might have surprised the men<br />

stationed beneath him. Despite thirty years in military service, he had never grown comfortable with<br />

the sight of the human form brought so low, reduced to just one more carcass in a room full of<br />

butchery.<br />

But he had been sent to view them, and view them he had done.<br />

There was little to report. An old white woman. An old dark man. Neither corpse seemed<br />

inclined to reveal what had killed it, much less who. The lady was of an age and constitution that if<br />

she had simply fallen to the floor of the Byculla Club it would have been assumed she’d been taken<br />

by natural causes, and there likely would have been no investigation at all, even one as cursory as<br />

this. Only the fact that her servant had likewise succumbed minutes later had signaled that this was no<br />

heart failure or stroke. And thus, by so promptly joining his mistress in death, perhaps one could say<br />

that the fellow had performed his duty after all. At least a little. For now an event that might<br />

otherwise have been dismissed without thought was being classified as a crime.<br />

In fact, this woman’s husband - just as frail as she and very nearly as dead - languished<br />

even now in the military jail, although why a sixty-nine year old man would kill a seventy-one year<br />

old woman, the officer could not hazard a guess. Women were vexing, this he knew, but no matter

how unpleasant this particular old biddy had been, it seems that after surviving decades upon decades<br />

of matrimony, any man could white-knuckle his way to the end.<br />

So what might have prompted the old duffer to put her away, and – even more troubling a<br />

question - to take the manservant as well?<br />

With a sigh that was louder than his earlier curse, the officer pushed away from the table,<br />

pausing one last time as he left the room to consider the scene. No matter how pressing the need to<br />

conserve ice, whoever had made the decision to entwine the bodies of Rose Weaver and Pulkit Sang<br />

was a fool. When it came time to separate them, their limbs would likely break.

Chapter One<br />

Leeds, England<br />

Rosemoral Estate – The Peacock Lounge<br />

August 16, 1889<br />

12:20 PM<br />

“It seems that we are running the risk of becoming the last thing I thought we’d ever be,”<br />

Tom Bainbridge said, settling back in an elegantly shabby armchair and flicking his cigar in the<br />

general direction of an ashtray.<br />

“And what is that?” his brother William asked, a bit warily. Tom may be the baby of the<br />

family, but he was also wildly confident, stunningly clever, and far too fond of his drink. It all added<br />

up to unpredictability, the one thing William couldn’t abide.<br />

“I’m rather afraid to say,” Tom said. “I might be struck by lightning for daring to utter the<br />

words aloud.”<br />

“It’s a cloudless day,” William said, with a glance toward the wide French windows.<br />

“Risk it.”<br />

“We appear to be teetering on the cusp of being a happy family,” Tom said.<br />

William chuckled, with both surprise and pleasure, for now that he stopped to consider<br />

it, Tom was quite right. The next day, their sister Leanna would marry Dr. John Harrowman, whom<br />

she incessantly referred to as “her intended,” and it seemed that whatever Leanna intended to have,<br />

she ultimately did. William had to admit that John was a pleasant enough chap, although a bit too<br />

inclined toward liberal causes, and he supposed that John was even what the ladies would call<br />

handsome, with his tall slender frame and wavy dark hair. The newlyweds would of course settle at<br />

Rosemoral following the obligatory honeymoon abroad, and shortly after they returned, William<br />

himself would march to the altar. He would be accompanied by the amiable heiress of the neighboring<br />

estate, Hannah Wentworth.<br />

“I like Hannah,” Tom said, as if reading his mind. “She seems quite…forthright.”<br />

“That she is,” William agreed, with another chuckle. Some gossips might claim his own<br />

intended to be plain, even horse-faced, with an unwomanly degree of interest in livestock and<br />

farming, but she suited William admirably well. And besides, when they combined the acreage of<br />

Hannah’s estate with that of Rosemoral, the result would be the finest farm in three counties, with<br />

William as manager of it all.<br />

“Thank God she escaped the clutches of Cecil,” Tom added. “Now that time has passed<br />

and the dust has settled, it seems completely evident that he was the root of all our problems from the<br />

start. Well, Papa was actually first, I suppose, but after he got himself thrown from his horse, Cecil<br />

stepped into the vacancy rather well, did he not? Gambling and cheating and sowing discord in every<br />

corner.”<br />

“Discord?” asked William. “Is that the proper word for what Cecil sows?”<br />

The brothers sat for a moment in silence, each man lost in his own thoughts. When their<br />

grandfather’s will had quite unexpectedly – quite shockingly, in fact – left Rosemoral to Leanna and<br />

not to one of her three brothers, Cecil had exploded with rage. As it had turned out, his gambling<br />

debts were far more severe that anyone had guessed, and he was being aggressively pressed for<br />

payment by men he had once counted as friends. But even after losing Rosemoral, Cecil had one final

ace up his sleeve – his courtship of the fabulously wealthy Hannah Wentworth. Unfortunately for<br />

Cecil, Hannah had found him canoodling with a maid in the rose bushes and thus she too had slipped<br />

through his hands.<br />

And then, after causing the sort of “discord” that neither Tom nor William could bear to<br />

contemplate in the light of this lovely summer morning, Cecil had disappeared. The official story<br />

doled out to Leanna and their mother was that he had gone heiress-hunting in the fertile fields of<br />

America, a lie which anyone with any acquaintance with Cecil would readily believe.<br />

The last nine months had brought great changes to the family. Within weeks of Cecil’s<br />

absence it was clear he’d been a cancer; once removed, the body promptly began to recover. Their<br />

mother Gwynette, worn down with worry over her middle son’s incessant escapades, had regained<br />

her health and even a bit of her legendary beauty. Leanna had promptly hired William as her estate<br />

manager, the function he had always secretly wanted, which allowed William to pay his uninspired<br />

but persistent court to Hannah Wentworth, who was a far better match for him than she had ever been<br />

for Cecil. Hannah seemed perfectly aware that she was fortunate to have avoided becoming yoked to<br />

Cecil, and transferred her affections from one brother to another with minimal fuss. Leanna’s own<br />

attention was focused on planning the wedding and helping her fiancé John establish his medical<br />

clinic. Their new brother-in-law seemed destined to become the saint of the county before his work<br />

was finished, bringing the wives of rural farmers a level of obstetrics care previously only available<br />

in London. And through it all, Tom had remained in that laudable city, comfortably housed with their<br />

Aunt Geraldine and somewhat less comfortably learning the ropes in his new position as chief<br />

medical consultant to the first forensics unit of Scotland Yard.<br />

Thus there was peace in the valley – although both Tom and William knew that the ladies<br />

could not remain in the dark forever. The fact that Cecil had not returned for Leanna’s wedding was a<br />

strong hint he was not merely touring America, as was his complete lack of correspondence since<br />

November - a silence noteworthy even in a man with as little sense of family responsibility as Cecil.<br />

Leanna was too distracted by her role as bride to ponder the matter deeply, but their mother no doubt<br />

had already begun to suspect that he was truly on the lam from some latest bit of debauchery. It would<br />

all have to be faced someday, but not, it would seem, on this particular day. At least for the<br />

meantime, Gwynette Bainbridge seemed more than content to let things drift along precisely as they<br />

were – unquestioned and calm.<br />

“He shall resurface eventually, you know,” Tom said.<br />

“Let us hope not.”<br />

“Hope strikes me as a highly imperfect defense against the evils of the world,” Tom said,<br />

reaching for the tumbler of brandy on the table besides his smoldering cigar. Spirits at noon were<br />

never a good sign, William thought with a small tickle or worry, but perhaps Tom was merely<br />

relaxing before the social duties of the weekend began.<br />

“I know you have devoted your life to science and whatnot,” William said, “and I think<br />

that’s a fine thing. Precisely as Grandfather would have wanted it. But it seems a dangerous path<br />

you’re on, pursuing truth no matter what the cost.”<br />

Tom shrugged, although he was feeling anything but nonchalant. He was just past twentyone,<br />

while William had passed thirty, and he feared some sort of lecture was coming. “I am Scotland<br />

Yard now, as you know. And thus yes, of course I am devoted to the pursuit of truth at all costs.”<br />

“Unofficially Scotland Yard.”<br />

Tom took a gulp from his glass. “Quite unofficial. I am a volunteer, in fact, which is an<br />

embarrassing thing for a man to say aloud. Makes me sound like some well-to-do matron hell-bent on

ehabilitating the whores. But Trevor Welles never makes a distinction between me and the others on<br />

the team, so I can’t see why you should.” He put the glass back on the table and pulled in a slow<br />

breath. There was nothing like an older brother, Tom reflected, to make you feel like a child again.<br />

To knock you right back to the nursery with just a few well chosen words. Best to revert the<br />

conversation back to its original topic. He nodded toward his brother and asked, “But seriously,<br />

don’t you ever wonder what became of Cecil?”<br />

“Of course I wonder,” William said, his gaze moving to the wide open windows and the<br />

soft green lawns of Rosemoral beyond. “Only a fool wouldn’t wonder and only a fool wouldn’t<br />

worry. But, trust me on this, Tom. Some stories are better left untold.”<br />

***<br />

The Gardens of Rosemoral<br />

12: 50 PM<br />

“I knew the Bainbridge family was rich.” Trevor said, “but somehow I never grasped<br />

that they were quite this rich. Actually seeing the estate in all its glory puts another perspective on the<br />

matter, does it not?”<br />

“Indeed it does,” said Rayley. “How many bedrooms would you guess the house to<br />

have?”<br />

The three official members of the Scotland Yard forensics team – Detectives Trevor<br />

Welles and Rayley Abrams, along with bobby Davy Mabrey – were strolling the gardens of<br />

Rosemoral while the three unofficial members – Tom, his Aunt Geraldine, and Geraldine’s<br />

companion Emma Kelly – were presumably somewhere inside. As a close friend of Geraldine’s and<br />

a frequent guest at her legendary dinner parties, Trevor had certainly enjoyed the benefits of the<br />

Bainbridge family fortune on many occasions, but in the city the money at least was contained within<br />

the walls of Geraldine’s handsome home. Here, in the country, it seemed to spill out in all directions,<br />

engulfing every meadow and hill within view.<br />

“I have no idea the number of bedrooms,” Trevor said, “but bedrooms at least serve a<br />

definite purpose. What I find truly amazing about Rosemoral is all these vague public rooms which<br />

seem to have no function at all. Consider this. Last night, Tom asked me to have a drink with him in<br />

the Peacock Lounge. Now what would you imagine a Peacock Lounge to be?”<br />

“I should think it was painted blue,” Rayley said mildly.<br />

“As would any sensible person,” Trevor said. “But as it turns out, it was a room filled<br />

with peacocks. Huge stuffed creatures fanned out across every surface, all staring at me with the most<br />

disconcertingly beady eyes. As a result, I fear I took more brandy than was prudent.”<br />

“I don’t like them either,” Davy blurted out. He was younger and shorter than the other<br />

two men, looking more like a school boy than an adjunct to the Yard. Knowing this, Davy had decided<br />

to treat his misleading appearance as an asset and not a liability; it seemed that suspects were often<br />

willing to confide any number of things in the harmless seeming bobby that they would never say in<br />

the presence of his superiors. “I don’t like the birds or the stuffed monkeys or that pig thing with all<br />

the bristles standing at the end of the hall. I was looking for the privy in the middle of the night and<br />

ran right into it. For a moment I thought it was real and set to charge me.”<br />

“There are indeed many remarkably convincing examples of taxidermy within these<br />

walls,” Rayley said with amusement. “Evidently the grandfather was quite the naturalist and a sworn<br />

devotee of Darwin. Tom’s own eccentricities make a bit more sense now, do they not?”<br />

“Leanna’s too,” Trevor said, his eyes coming to rest on a full-blooming rose. “I keep

forgetting, Rayley, that you were gone to Paris and didn’t know her like the rest of us. But she is quite<br />

extraordinary, I assure you.”<br />

A small pause. That silent second, maybe two, that always seemed to follow any<br />

mention of Leanna’s name. For Trevor had been enchanted by the young heiress as well, but - unlike<br />

John Harrowman, the man she would marry on the morrow - he had lacked the courage to pursue his<br />

inclinations. Trevor was notoriously plodding with women, seeming to somehow always end up as<br />

more brother than lover, and Rayley suspected that his friend might now be well on the way of making<br />

the exact same mistake with Emma Kelly that he had once made with Leanna Bainbridge.<br />

Wake up, Rayley thought, following Trevor’s gaze toward the rose bush. For pretty<br />

young girls are like these flowers. There seem to be so many, blooming here around us, each more<br />

delightful than the last. But someday soon, with the slightest turn of the sun, they shall all be gone.<br />

Aloud, he ventured a joke. “And what made Leanna so eccentric? Besides, of course,<br />

the fact she was mad enough to prefer another man to you?”<br />

It was a risk. A test of how well Trevor might manage attending the wedding tomorrow.<br />

To Rayley’s relief, as well as that of Davy, Trevor laughed.<br />

“Just as well it didn’t work out,” he said. “The girl is lovely, no doubt of that, but can<br />

either of you imagine me here, the master of a country estate?” He tapped the rim of his bowler with<br />

a fingertip and shook his polished walking cane at them. “See? Even my clothes are quite wrong for<br />

the task.”<br />

“As is your pace,” Rayley said. “We are supposed to be strolling the garden, are we not,<br />

and yet I swear we have passed this one particular rose bush at least three times. You stride about<br />

like a man rushing to catch a train, not one who is out to admire nature. And what crimes should you<br />

find to investigate, here in the hills?”<br />

“The theft of a cow?” suggested Davy.<br />

“Indeed,” said Rayley. “I can see you now. Constable Welles, formerly of Scotland<br />

Yard, dispensing justice on the issue of Bossy’s true owner. Summoned to the home of the village<br />

drunk who has just set upon his wife. Helping to pull overturned carts from the ditch.”<br />

“True, true, all true enough,” said Trevor. He knew that tomorrow morning, at the<br />

moment when Leanna Bainbridge became Leanna Harrowman, there would still be a pang in his<br />

chest, but he appreciated his friends for trying to make him feel better about it. He turned slowly, his<br />

shoes crunching against the pebbles as he took in the estate from all directions. But it was a futile<br />

exercise. North, east, south, and west, the view was all the same – green grass, stone walls, softly<br />

undulating hills punctuated with the occasional sheep.<br />

“True enough,” he said again, this time with more conviction. “It’s all quite perfect to<br />

the eye, is it not? The whole scene seems designed for human happiness – or perhaps even that more<br />

elusive thing they call peace. But I would never have found my purpose here.”<br />

***<br />

Rosemoral - Leanna’s Bedroom<br />

12:50 PM<br />

Leanna emerged from behind her dressing screen with Emma close behind her, picking at<br />

the folds of her voluminous white silk skirt. Leanna swirled and then looked at the three women<br />

seated before her expectantly.<br />

“Flawless,” said her mother Gwynette.<br />

“Exquisite,” said her future sister-in-law Hannah.

“Glorious,” said her Great-Aunt Geraldine, who then promptly surprised them all by<br />

reaching for a hankie to dab away tears. It was not odd that she would show emotion, for Geraldine<br />

Bainbridge was a fiercely passionate woman - an enthusiastic patron of a variety of causes and given<br />

to exaggeration, gossip, and verbosity by nature. But it was surprising beyond measure that she<br />

would be moved to tears by the sight of a girl in a wedding gown. Geraldine had not only managed to<br />

reach the age of sixty-seven without ever having been, in her words, “netted and mounted,” but had<br />

been known to write vehemently feminist letters to the editor of the London Star, the most famous of<br />

which had compared marriage to slavery.<br />

“Darling Auntie,” said Leanna, dipping to give Geraldine a hug. “None of this would<br />

even be happening if weren’t for you. If I’d never come to London, I never would have met John, and<br />

who knows what would have become of me then?”<br />

Seeing as how you are both wildly beautiful and wildly rich, Emma thought drily, what<br />

most likely would have become of you is that you would have married someone else. Probably not<br />

someone with the elevated social consciousness of Saint John Harrowman, but no doubt another<br />

man who was equally handsome, charming, and aristocratic. For you are, without question, the<br />

single luckiest human being I have ever known.<br />

But of course she did not say these words out loud. Despite the oceanic gap between<br />

their status in the world, Emma was genuinely fond of Leanna and supposed, against all odds, that<br />

they might even be called each other’s best friend. Best female friend, at least. They were both<br />

women who had found themselves surrounded by men – Leanna through the fluke of having been born<br />

with three brothers and Emma through her unlikely position as the linguistics expert on the Scotland<br />

Yard forensics team. Under the circumstances, they were gratified to have befriended each other at<br />

all, and Leanna now turned towards Emma, her pale eyebrows lifted in question.<br />

“You are the most beautiful bride I have ever seen,” Emma promptly confirmed. “And<br />

John will no doubt be the most handsome groom and the wedding tomorrow shall be so unrelentingly<br />

perfect that we shall all be struck deaf, dumb, and blind simply by having witnessed the experience.”<br />

“Good,” said Leanna decisively, turning to consider her reflection in the mirror. “For<br />

that was precisely the effect I wished to achieve. In fact, if a single guest leaves the church tomorrow<br />

in full possession of his senses, I shall count myself a failed bride.”<br />

“Do you want to put on the veil?” Emma asked. “For it sets the gown off to perfection.”<br />

Just then there was a rap at the door and one of the maids entered, bearing what<br />

appeared to be a letter on a silver tray. The tray was large and obviously heavy and she advanced<br />

toward them with a slow and measured step. Enough ceremony to still the chatter of the room. Emma<br />

wondered if such rigmarole was typical at Rosemoral or if the staff was putting on special airs in<br />

honor of the wedding.<br />

“Just came for you, Miss,” said the girl.<br />

“Thank you, Tillie,” Leanna said. She took the letter in both hands and considered it<br />

with a quizzical frown. “To the Bride of Rosemoral,” she read. “Heavens, that’s rather prosaic, is it<br />

not?”<br />

“And look at that envelope,” Emma said, peering over her shoulder at the crinkled,<br />

honey-colored paper and the explosion of different colored stamps haphazardly crammed into the<br />

right hand corner. “It appears to have come through the wars.”<br />

“Little wonder, it’s from India,” Leanna said slowly, squinting at the spidery handwriting<br />

on the front of the envelope. “Mother, do we know anyone who is stationed in India?”<br />

“Not that I’m aware of,” Gwynette said. “Geraldine, are there any old family friends

who might –“<br />

“Read it,” Geraldine said.<br />

The order, so plainly stated and thus so unlike its speaker, seemed to stun them all.<br />

Leanna tore at the envelope and extracted a single sheet of paper, as thin and yellowed as its sheath,<br />

and, with a small intake of breath, began to read.<br />

My darling. I have no right to call you that or to ask you now for help. I have no right to ask<br />

you for anything at all, as we both well know. But I find myself in a spot of trouble and you’re the<br />

only person I can think to turn to in my hour of need.<br />

It’s Rose, as if you haven’t already guessed. They say I’ve gone and killed her.<br />

“That’s it?” Gwynette said. “It isn’t signed?”<br />

Leanna shook her head. She had gone a little pale.<br />

“How extraordinarily odd,” Hannah said, leaning forward, a frown settling across her<br />

heavy features. “Gone and killed her, he says? The letter must have been delivered here by mistake.”<br />

“I don’t see how,” Leanna said. “We’re the only Rosemoral in all of England.”<br />

“Is there a date?” Geraldine asked. Her voice was so devoid of inflection that it<br />

sounded barely human and Emma looked at her with alarm. Experience had taught her that Geraldine<br />

shrieked and railed over mice caught in traps, oversalted soups, and typhoons swarming countries so<br />

far-flung that most of the citizens of London couldn’t have found them on a map. If Geraldine was<br />

calm, then the situation must be very bad indeed.<br />

Leanna turned over the envelope. “August 9,” she said slowly. “Posted a full week<br />

ago. Do you know the meaning of this, Aunt Gerry? Who might have sent me such a strange letter?”<br />

“No one, darling,” Geraldine said. “That letter is meant for me.”

Chapter Two<br />

Rosemoral - Dining Hall<br />

August 17<br />

10:12 PM<br />

Thirty-two hours later, with the newlyweds happily dispatched on a honeymoon tour of<br />

Italy, the Thursday Night Murder Games Club convened to discuss the remarkable matter of<br />

Geraldine’s Indian letter.<br />

It was not a Thursday night, of course. Nor were they ensconced in their normal<br />

location, Geraldine’s opulent dining room in London. But the tables and chairs of Rosemoral would<br />

serve just as well, and, thanks to the hospitality of the bridal family, good food and fine wine seemed<br />

to flow as steadily in the country as in the city.<br />

Wealth blurs certain distinctions, Trevor thought, leaning back in his seat to better<br />

survey the pleasant scene before him. The prosperous can be cool in the summer and warm in the<br />

winter; they bring gardens into the city and fine cuisine into the country. Reality is not the<br />

stumbling block for the rich that it seems to be for lesser mortals, but merely something to be<br />

managed. A clever hostess with ample funds at her disposal can easily transport her guests into<br />

any time and place that she wishes.<br />

Gwynette, William, and Hannah had departed the table, along with the handful of<br />

houseguests who had remained after the wedding. The servants had likewise made their tactful<br />

retreat, leaving only the Murder Club: Trevor, Rayley, Davy, Tom, Emma, and, of course, Geraldine.<br />

Normally nonchalant in all social situations, she seemed unusually anxious tonight. Trevor had<br />

noticed that her napkin lay twisted beside her plate and her wine glass was untouched.<br />

“Perhaps we should start by asking you to tell us,” he said gently, “the basics of your<br />

history with the man who wrote the letter. This Anthony Weaver.”<br />

Geraldine had surely anticipated the question. Had surely been mulling the matter all<br />

day. And yet she hesitated, her eyes narrowing as she focused on the copse of candles clustered in the<br />

center of the table, their light flickering low with the lateness of the hour.<br />

“I met him on a ship,” she finally said. “A ship bound for India. It was 1856 and so I<br />

was…I suppose I must have been just at thirty-five years old.”<br />

This information, brief as it was, seemed to trigger a response in each person seated at<br />

the table. But it was the date of the voyage that intrigued Trevor, and a quick glance at Rayley<br />

confirmed that his fellow detective had also noted its significance.<br />

1856 was the year before the Great Mutiny.<br />

“They called us the fishing fleet,” Geraldine went on, with a shaky and mirthless laugh.<br />

“For if you were a woman who had passed marriageable age and your prospects in England had<br />

grown limited, then they promptly packed you off to India. The men there outnumbered the women ten<br />

to one and it was said that even the ugliest and most disagreeable of females could easily catch a<br />

husband among the officers of the Raj.”<br />

“You traveled halfway around the world looking for a husband?” Emma said, the<br />

disbelief in her voice echoing the thoughts of them all.<br />

“Of course not,” Geraldine said sharply, and for the first time all evening she reached for<br />

her wine glass. “Marriage is a trap, especially for women, and most especially for a woman like me.

But I wanted to see India. It was the grand adventure of my generation, and although my parents were<br />

quite tolerant for their time, even they would not allow their daughter to sail, as you say, halfway<br />

around the world to merely ride elephants and study Hinduism.” Geraldine’s mouth narrowed into a<br />

bitter little smile. “But they had every confidence in the fishing fleet, which had been designed for the<br />

transport of upper and middle class white women. The fleet promised safe passage, or at least as<br />

safe as that era allowed, and a host of acceptable chaperones. Far more than any of us would have<br />

liked, as it turned out.”<br />

“And what was Anthony Weaver doing on such a ship?” Rayley asked.<br />

“There were three types of passengers on board the Weeping Susan,” Geraldine said,<br />

leaning back. “We spinsters, of course. Dreadful word. And our chaperones, who were in many<br />

cases our age or even younger. You can imagine how that rankled. The chaperones were most<br />

frequently the wives of officers in the Raj, who lived in constant rotation between their duties to their<br />

husbands in India and the comforts of England. Those comforts in many cases included proximity to<br />

their children, who had most likely been sent home to boarding schools by the time they were six. No<br />

civilized person would attempt to educate a British child in India.”<br />

Geraldine sighed before continuing. “It is only in retrospect that I see how hard it must<br />

have been for the women. At the time it seemed as if marriage to an officer would be a madly<br />

exciting existence, certainly offering more variety and freedom than most wives enjoy. But through<br />

the years I have thought back on how they must have felt constantly torn between two places, ill at<br />

ease and guilty no matter where they happened to be. And ever in transit as well. For the journey<br />

was no easy matter in the fifties, before the canal on the Suez opened and steamers came widely into<br />

service. We sailed on clippers, if you can feature it, all around the base of Africa through the Cape of<br />

Good Hope. Passage took six weeks if luck was with you. Longer if the wind died.”<br />

“Six weeks?” Tom said in horror. “Even the grandest of adventures tend to wear thin<br />

after two.”<br />

“Indeed,” said Geraldine, smiling at her grand-nephew. “My point exactly.”<br />

“You said there were three categories of passengers sailing,” Trevor reminded her. “Yet<br />

you only spoke of the spinsters and their chaperones.”<br />

“The third group was a handful of British officers,” Geraldine said. “Reporting to their<br />

posts, returning home again, going back and forth on leave. Anthony, in fact, was traveling to rejoin<br />

his regiment in Bombay.”<br />

“Six weeks is a long time for a party of strangers to be cooped up together in tight<br />

quarters,” Tom said. “I imagine the ship would come to seem like a world unto itself. Quite apart<br />

from your real lives, wherever they lay, with all sorts of romances, feuds, and complications erupting<br />

among the passengers.”<br />

“But the trip may also have offered an unaccustomed burst of freedom for everyone<br />

aboard,” Emma said, further expanding on Tom’s thought. “The men about to take up military posts,<br />

the married women in respite between their own demanding roles as wives and mothers. And the<br />

unmarried ones…most of them away from the restraints of their parents for the first time, I’d<br />

imagine.”<br />

“You imagine quite correctly, both of you,” Geraldine said. Her eyes had taken on a<br />

dreamy look as she still gazed into the glow of the candles. “Life on board created the most dreadful<br />

ennui and claustrophobia, day after day all the same, and yet at times there were these moments of<br />

mad gaiety, for each of us was determined to seize her small pleasures wherever she could. A world<br />

into itself, just as Tom said. A world which we all knew would cease to exist the moment the ship

eached the harbor of Bombay. And it was in this setting that I first came to know Anthony Weaver.”<br />

“You said it was a six week transit if conditions were with you,” Emma said softly. “But<br />

on this particular voyage, I somehow suspect the winds died.”<br />

“Oh my, yes,” said Geraldine, and her large gray eyes filled with tears. “Quite right<br />

again, my darling. On this particular voyage, the winds died.”<br />

***<br />

The Bombay Jail<br />

6:14 AM<br />

“I understand you requested a priest, Secretary-General?”<br />

The old man had been dozing. He startled awake at the loud voice and, just as had been<br />

the case on each morning since he’d come to this dark and fetid hell-hole, for a slow moment he had<br />

wondered where he was. How had he come to be stranded here, on this narrow bench, with only a<br />

rough-ripped scrap of cloth stretched beneath him? With only a cup of flat water and bread of the<br />

most dubious origin to sustain body and soul?<br />

Most of all, how had he lost his power? Enough so that this insolent pup standing before<br />

him, the sort of pimpled, snot-nosed boy he wouldn’t hire to shine his shoes, might feel free to talk to<br />

him in this manner?<br />

“A priest?” the lad repeated, none too pleasantly.<br />

The old man winced. Asked for a priest, indeed. He might have been brought low in<br />

these last days, but not so low that he’d accept Irish-bred comfort. He would rather die with his soul<br />

unclean than pour his sins into Catholic ears.<br />

Struggling to contain his tremors and to push back the pounding in his head, he pushed<br />

himself to a sitting position and painfully twisted to better face the figure in the doorway. “There has<br />

to be some sort of military chaplain stationed nearby, does there not?” he said, with deliberate<br />

civility. For the first time in many years, he regretted his religious laxity. If he had attended services<br />

on a regular basis, he would have been able to ask for a suitable man by name.<br />

“We can scrape up someone, I’d wager,” said the boy, with a wide grin that catalogued<br />

the collective failures of British dentistry. “’Case you’ve decided to confess, that is?”<br />

Anthony Weaver - sixty-nine years of age and the former Secretary-General of the<br />

Presidency of Bombay Province, jailed for the murder of his wife and in the early stages of<br />

undiagnosed lung cancer – coughed and leaned back against the cracked plaster walls of his cell. The<br />

boy was right enough in his way, for Weaver did indeed have something to confess. Not to the crime<br />

he had been accused of now, not to killing Rose and her manservant , but to something else. Some<br />

long ago failing that had followed him, with the persistence of a shadow, for more than thirty years.<br />

So send them all, he thought, coughing again as the boy in the doorway at last<br />

disappeared. Send the chaplain and the vicar and the priest and the swami too, and the blind man on<br />

the corner who says he can see into your heart and heal it for a dozen rupees. Send them to this cell to<br />

hear confession of a mistake which was made before most of them were born. Not that it mattered. If<br />

Anthony Weaver knew anything, it was this: That life and love and country and duty…that all of these<br />

things faded in time. They came and went with the impartial cruelty of the Indian sun.<br />

But sin and sin alone is eternal.<br />

***<br />

Rosemoral - Dining Room<br />

10:34 PM

“I fear I am being obscure,” Geraldine said, wiping her eyes. “Which is the very last<br />

thing I intended to be.”<br />

“These are memories which have likely gone unspoken for some time,” Rayley said with<br />

sympathy, his own mind darting back to Paris and the extraordinarily ill-fated liaison he’d<br />

experienced there the past spring. How long would it be before he would speak of Isabel Blout, he<br />

wondered, and if he ever did, would he manage to tell the story in a sensible fashion?<br />

Geraldine smiled at him. “Thank you, dear, but Trevor has asked me to stick to the<br />

basics, so I must start again.” She gave a great exhalation to steady her nerves. “I boarded a ship,<br />

having assured my gullible parents and even my far-from-gullible brother that I wished to find a<br />

suitable man and marry. I had a substantial inheritance and a decent bosom, one of which I luckily<br />

still retain. But despite these assets, I had never been particularly marriageable by English<br />

standards. I was forceful, perhaps too full of opinions and too certain I was right. The eligible men in<br />

my circle had demurred, each in his turn. And so, when a full fifteen years after my lavish debut I<br />

remained unattached, my family was easily persuaded I might try my chances on the subcontinent.<br />

They took me to the port of London and onto the ship I went.”<br />

“And who was named your chaperone?” Trevor asked.<br />

“Very good, my dear,” Geraldine said. “Your question is quite apt and proves why you<br />

are the leader of us all. See there, everyone. A single shot in the dark and Trevor has managed to hit<br />

the one fact that will advance our story. For I was entrusted, you see, to the care of a matron a few<br />

years above my own age, a woman named Rose Everlee who was returning to India to join her<br />

husband in Bombay. And as fate would have it, Anthony Weaver was the dashing second in command<br />

in that same unit. Roland Everlee’s lieutenant, in fact, and also his closest friend.” Geraldine paused<br />

and frowned. “I say all that as a matter of course, but was Anthony truly dashing? They always use<br />

that word with officers, so I suppose he must have been. Or at least dashing enough for me.”<br />

“Rose Everlee introduced you to Anthony Weaver,” Trevor gently prompted.<br />

Geraldine nodded. “Before we had left London harbor. He was at my side even as I<br />

waved goodbye to Leonard and my parents.”<br />

But Emma was frowning. The letter which Leanna had read referred to a woman named<br />

Rose. Apparently over the course of the years, the commanding officer’s wife had somehow become<br />

the dashing lieutenant’s wife and, more to the point, had also managed to get herself murdered. What<br />

sort of tangle had Geraldine stumbled into?<br />

Noting Emma’s expression, Geraldine nodded again. “Yes, my dear, yes. As unlikely as<br />

it seems, my chaperone for the voyage was the very same woman who now lies dead. But perhaps I<br />

am getting ahead of myself once again.”<br />

“You sailed,” Trevor said pointedly.<br />

“We sailed,” Geraldine said. “Weeks upon the water, three of them spent simply drifting<br />

in the complete doldrums of the Indian Ocean, with nowhere to seek shelter except the terrifying<br />

prospect of the African coast. The captain assured us that if we took harbor there we should be<br />

devoured on sight, and, fools that we were, we believed him. And so we sat. Too little wind, too<br />

much water. Too little food, too much sun. It was during those doldrums that Anthony and I...we<br />

indulged ourselves, I suppose that is the best way to say it. In ways which would not have been<br />

allowed in London, or even Bombay.”<br />

Silence. Everyone waited.<br />

“The months that followed,” Geraldine said softly, “were the happiest of my life. But

also the most confusing. The uprising came, you know. Not nearly as swift or unexpected as the<br />

reports claim. As military men, Roland and Anthony were both aware there was discontent among<br />

the native populace, but most of the reported trouble had been inland and it was widely believed that<br />

the coastline, and thus Bombay, would be safe.” Geraldine grimaced. “Perhaps I should say that it<br />

was widely believed that all the English in India would be safe. The men and women of the Raj were<br />

rather naïve, you see. They thought that the Indians loved them unquestioningly, as children love their<br />

parents. But Anthony knew better. He understood that the danger was real and much closer than<br />

anyone was willing to admit. In fact, it is almost as if he had a premonition. Against all my romantic<br />

and rather foolish protests, he insisted that I return at once to England.”<br />

“And thank God that he did,” said Tom. Geraldine’s story had left him very nearly in<br />

shock, as evidenced by the fact he had stopped drinking. As many evenings as he had spent in his<br />

aunt’s home, he had never heard anything about a man named Anthony Weaver or even a voyage to<br />

India. Had never known how close his beloved Aunt Gerry had been to being caught up in the<br />

infamous Indian Mutiny of 1857, which had resulted in the murder of nearly 400 British, a sizeable<br />

percentage of them women and children.<br />

“What of Rose?” Trevor said.<br />

“Roland wished for her to leave as well, but she was, at the advanced age of thirty-nine,<br />

at last expecting a child and thus her doctors forbad the trip,” Geraldine said. “As it turns out, their<br />

advice was sound, for she delivered safely in Bombay. But poor Roland was killed in the uprising<br />

before he ever got to see his son, and then Anthony -“<br />

Here she stopped and Tom was aware that around the table they were all holding their<br />

collective breath. The candles had sunk into a puddle, and the light was nearly gone.<br />

“The next time I heard from Anthony,” Geraldine finally continued, “was when I<br />

received a letter explaining to me that he had married his best friend’s widow and was prepared to<br />

raise Roland’s son as his own. He said that his loyalty to his captain surpassed all others, especially<br />

in light of the horrid manner in which the man had died. Roland was a true hero, you see, impaled on<br />

a host of swords as he sacrificed himself trying to save a woman and her five children.”<br />

“And you never saw Anthony again?” Tom said. “Never heard from him at all until<br />

yesterday?”<br />

Geraldine shook her head. “As far as I know, neither Anthony nor Rose ever returned to<br />

England, not even for a visit.”<br />

“Because their rapid marriage was a scandal?” Trevor asked. The memories were<br />

obviously painful, but it seemed a greater kindness to treat the story as a case study, and thus<br />

impersonal. Offering sympathy over a jilting thirty years in the past would only insult a woman as<br />

independent as Geraldine.<br />

“It wasn’t a scandal at all,” Geraldine said matter-of-factly. “You must remember that<br />

India is an outpost, a colony, with few British men and even fewer women. And the conditions were<br />

far more primitive in the fifties. Rapid marriage and, if required, rapid remarriage were the norm.<br />

No, I think it was because India offered a man like Anthony, who had ambition but limited resources,<br />

a chance to make his fortune. Staying there must have suited him.”<br />

“Did it suit Rose?” said Emma.<br />

“Not quite so much, I’d imagine,” Geraldine said, with another small private smile, this<br />

one of a manner Emma found impossible to interpret. “She complained of the heat and the bugs the<br />

entire time I knew her and she never learned to tolerate the food. But my sources assured me that<br />

Anthony rose up the ranks well enough through the years, so I suppose their creature comforts

expanded with his career.”<br />

“I have a question, Ma’am,” Davy said. It was the first time he’d spoken since dinner.<br />

“I’d imagine you all have any number of questions,” Geraldine said with a snort of<br />

amusement. “But what is yours?”<br />

“Meaning no disrespect, ma’am, but do you think it is possible…I mean, seeing as how<br />

they were on the same ship together when you met, coming back from England at the same time… and<br />

then haste of the…with her husband barely dead…I don’t know quite how to say it, ma’am, but when<br />

you look at the sequence…”<br />

“You’re asking if it were possible that Anthony’s true affection was directed toward<br />

Rose all along?” Geraldine said. “That poor Roland was a cuckold, that I was their cover, and that<br />

Anthony’s professed loyalty to his captain was really just an excuse to stay close to the wife? Of<br />

course it is possible. It was, in fact, the first thought that occurred to me when I got Anthony’s letter<br />

all those years ago.”<br />

Trevor was ashamed that this particular theory – which sounded so plausible when<br />

clothed in Geraldine’s plain language – had not occurred to him. It had been neither his first thought<br />

nor his fifth. And judging by the expressions around the shadowy table, neither Emma, Tom, nor<br />

Rayley had imagined it as well. Painful to think that among them, only Geraldine and Davy were<br />

clear-headed enough to see through the haze of romance and adventure to the tawdry possibilities<br />

beneath.<br />

Emma recovered first. “Speaking of Anthony’s letter,” she said. “The second one,<br />

yesterday’s, was addressed to the ‘Bride of Rosemoral.’ Why should he call you such a thing?”<br />

“A silly spasm of pride,” Geraldine said. “Despite the fact he presented it as mere duty,<br />

being tossed over for Rose was a blow. I wrote him back that I too was about to be married and spun<br />

quite an elaborate tale around the event, even going so far as to suggest the Queen and Prince Albert<br />

would be in attendance. And I believe I may, in my foolishness, have signed this fanciful missive<br />

‘The Bride of Rosemoral.’ Strange he would remember that now, after so long. Perhaps he did it to<br />

mock me. After all, if he followed my history even half as avidly as I followed his, he would know<br />

that I remain Geraldine Bainbridge.”<br />

“I can’t think why he’d mock you,” Tom said. “Especially when requesting your help.”<br />

“And that’s the real issue here, is it not?” Trevor asked. “Putting aside the man’s<br />

audacity in even asking, what the devil sort of assistance does he expect you to provide?”<br />

“Money?” Geraldine said archly. “Everyone always seems to need a little more of that<br />

in times of trouble. British council for his defense, I’d imagine? An investigation, almost certainly. I<br />

shall ask him, of course, when I get there.”<br />

Another silence fell around the table. Not a pleasant, reflective silence, but the sort of<br />

nervous, anticipatory silence that precedes a gunshot, or a storm.<br />

“Get there?” Tom finally asked warily.<br />

“Travel to India, even now,” Rayley broke in, “can be extraordinarily-“<br />

“Geraldine, you don’t truly-“ Trevor began.<br />

“Well of course I must go, darlings,” Geraldine said. “Anthony will find no justice in<br />

Bombay, not unless someone somewhere stirs to help him. We all know that.”<br />

“But you owe this man nothing,” Trevor sputtered. “Less than nothing.”<br />

“You asked for the basic facts of our story,” Geraldine said, a trifle sharply. “And the<br />

basics were precisely what I gave you. But matters of the heart are never so simple as they might<br />

seem to those on the outside, looking in.” She glanced around the table, at the shadowy forms of the

others and then took a final, trembling sigh. “For you see, I have my regrets as well.”

Chapter Three<br />

Scotland Yard<br />

August 18<br />

2:14 PM<br />

The next afternoon Trevor was back in his office in the basement of Scotland Yard,<br />

frowning at a telegram. He was so preoccupied that he scarcely looked up when Rayley entered.<br />

“She’s not Ripper,” Rayley said briefly.<br />

“Never thought she was,” Trevor murmured, his eyes flitting across the paper in his hand<br />

a final time. The fact that Jack the Ripper remained at large was a black eye that the whole of<br />

Scotland Yard wore, and some might guess that Trevor himself, as principal detective on the case, felt<br />

a special level of guilt at the fact the crimes had never been solved.<br />

But nothing could have been further from the truth. Trevor knew in his heart he had done<br />

all he could do to capture Jack, and there was a certain peace in that knowledge. Failure, Trevor had<br />

sometimes reflected, often seemed to bring more peace of mind than success, for success had to be<br />

constantly maintained while only failure allowed a man to close a door and truly leave the past<br />

behind.<br />

The rest of the Yard did not share in this philosophy. They were still looking over their<br />

collective shoulder for Jack, and thus calling in the forensics team each time a female had the<br />

misfortune to be knifed in the East End. That was, in fact, why Rayley and Tom had been fetched an<br />

hour earlier to examine the remains of a woman who had, almost without question, been killed by her<br />

own husband. And there was no telling when the paranoia would finally end. They had put Mary<br />

Kelly in the ground nine months ago. She was not only the Ripper’s last known victim but also<br />

Emma’s sister, and thus every detail of that investigation was burned into Trevor’s memory as if it<br />

had been branded there by a hot iron. No, he would never forget the case, never fully be over it, and<br />

yet – nine months was the length of a human gestation. The amount of time it took to bring new life<br />

into the world and so, it seemed to Trevor, a proper amount of time for a man to likewise reinvent<br />

himself. To find a new incentive for his work. The Ripper had slowly melted in his mind to an<br />

amorphous, uncatchable figure of evil. The enemy Trevor knew he would never vanquish, for the<br />

instant the neck of one killer snaps with the rope, another victim is crying out from another street.<br />

In short, Trevor felt about criminals much the same way Jesus had spoken of the poor.<br />

He knew they would always be with him.<br />

And so he had dispatched Tom and Rayley to make study of this latest victim’s knife<br />

wounds and to record the statements of her doubtlessly raving husband. He had spent the resultant<br />

privacy of the last hour composing a telegram to the military police of the Bombay Presidency. His<br />

questions had been answered with stunning promptness, almost as if someone in that dusty little field<br />

office had been waiting anxiously for an inquiry from Scotland Yard and had all the particulars at the<br />

ready.<br />

“See here,” Trevor said, sliding the paper across the table toward Rayley.<br />

“Heavens,” Rayley said, pulling up a chair with a scrape. “This may be the longest<br />

telegram I’ve ever seen.” He scanned it quickly, a pucker appearing between his thin eyebrows.<br />

“Miss Bainbridge said India is where the ambitious men used to go. It would seem that is still the<br />

case.”

“What makes you say that?”<br />

“This man, this Henry Seal, who has sent the missive…I get the impression he’s trying to<br />

make a name for himself, that’s all. The report is suspiciously detailed. And yet he dispatched this…<br />

this…what was the fellow’s name? This Morose or Morass or whatever he was to examine the<br />

bodies.”<br />

“It’s Morass, and I doubt Seal was the one who sent him,” Trevor said, drawing the<br />

paper back across the desk. “The double structure of India’s government leads to much overlap of<br />

duties and confusion, so I can only assume Morass and Seal come from different divisions. You have<br />

the Viceroy, of course, who reports to Parliament and as you see by his title, Seal is most likely with<br />

them. And then each geographic region is its own presidency, with its own Governor, and my guess<br />

would be that Morass is from that division. A group of military boys who are undoubtedly in over<br />

their heads but still reluctant to call in the Viceroy’s men. You know, a bit like the local coppers<br />

always resent Scotland Yard when we come crashing about, telling them their business. Only in this<br />

case it’s worse because there is no clear chain of command.”<br />

Rayley raised an eyebrow. “You know all this off the top of your head?”<br />

Trevor chuckled. “I will admit that I’ve spent the best part of the last hour doing a study<br />

of how justice is dispensed in India. And the answer appears to be ‘badly.’ Geraldine is quite right.<br />

Even with his exalted title, there’s no telling what sort of investigation or trial Anthony Weaver can<br />

expect.”<br />

“Do you think she’s really going?”<br />

“If Gerry makes up her mind on something, no one can stop her. Speaking of which,<br />

where’s Tom?”<br />

“Got a bit of blood on him during the examination upstairs,” Rayley said with a shrug.<br />

“Said he was going home for a wash and a change of shirt.”<br />

“And you believed him? You let him go? He’s plotting with his aunt, and there’s no<br />

doubt about it. My guess is both he and Emma will be on that same steamer to Bombay.”<br />

“What if they are, Welles?” Rayley said, leaning back in his chair. “Tom and Emma are<br />

unpaid volunteers. They’re free to do exactly as they please and besides, anyone can see that Miss<br />

Bainbridge should not undertake such a lengthy journey alone.”<br />

“I know what you’re thinking,” Trevor said, “but we can’t ask the Queen to release us<br />

again, not so shortly after Russia. Or Paris, for that matter.”<br />

“Whyever not? We have no pending case.”<br />

“Not at the moment, no.”<br />

“And we went to Russia entirely at her behest. To assist her in a private matter of her<br />

own, as I recall.”<br />

“Nonetheless, I won’t go to Her Majesty yet again asking for leave,” Trevor said<br />

resolutely. “Not so soon. And not for some ridiculous case of marital violence. A man kills his<br />

wife. A tragedy, certainly. But of the most common sort, and hardly one that requires our specialized<br />

skills. No, we shan’t go with Geraldine, no matter how she begs.”<br />

“Has she begged?”<br />

“Not yet,” Trevor admitted. “But she will.”<br />

“I wonder if the Queen has heard of this sad affair,” Rayley mused.<br />

“Why should the Queen concern herself with something like this?”<br />

“Come now, Welles,” Rayley said. “The dead woman, after all, is the widow of a well<br />

known military hero, a man with statues cast in his honor. The accused is a retired Secretary-General,

with a distinguished record of his own. If our sojourn to St. Petersburg has taught us anything, it’s that<br />

Her Majesty takes a dim view of any crimes which involve servants of the Crown.”<br />

“It’s a domestic affair,” Trevor repeated, his face flushed. “The murder may have<br />

involved more celebrated people in a more exotic setting, but I assure you that the Weaver case is at<br />

heart no more compelling than the story of that baker’s wife who lies bloody and bludgeoned above<br />

us. Our duty is to the Queen and the citizens of London. Weighed against that, the fact that Gerry knew<br />

this man a lifetime ago counts for nothing.”<br />

“And yet,” Rayley said, gazing innocently up toward the water-stained ceiling, “for some<br />

reason you have spent the last hour reading up on the legal system of the Bombay Presidency.”<br />

***<br />

Windsor Castle<br />

3:30 PM<br />

“Of course we are familiar with the Weaver case,” the Queen said.<br />

So she is back to the royal “we,” Trevor noted with bemusement. During their recent<br />

trip to Russia he and the other members of the team had traveled in close congress with the Queen and<br />

her granddaughter - so close, in fact, that on more than one occasion they had stood witness to the<br />

most un-royal sort of family rows. But if he had thought that such a sustained period of enforced<br />

intimacy was to alter the nature of his working relationship with Her Majesty, it was evidently not to<br />

be the case. Victoria seemed capable of passing through levels of formality as easily as she walked<br />

through the rooms of Windsor Castle. The Queen had granted his request for an audience with a<br />

promptness which suggested she had not forgotten his services to her family during the Russian caper,<br />

but now that he was seated in her private office, her infamous hauteur had returned.<br />

“The sacrifices made by Roland Everlee,” the Queen continued, “earned him the highest<br />

honors that the Crown can bestow. Posthumously awarded, of course, but he is still regarded far and<br />

wide as the very example of British honor. And thus the murder of his widow, even so many years<br />

after the fact, would most naturally be brought to our attention.”<br />

Victoria shifted in her seat. Short and plump, she never seemed wholly on balance atop<br />

her enormous chairs, and more than once Trevor had indulged the whimsical notion that the Queen<br />

might actually tumble from her padded cushions and roll across the floor. Now she looked<br />

impassively at Trevor and added, “Perhaps the better question is, why has a Scotland Yard detective<br />

taken interest in such a matter? Are the streets of London so silent that you must search halfway<br />

across the globe to find a forensic challenge?”<br />

She had them there.<br />

“A friend brought the case to my attention,” Trevor admitted. “She is connected to both<br />

the victim and the accused. Or at least she was connected to them long ago.”<br />

“We presume you refer to Geraldine Bainbridge?”<br />

Trevor looked at the Queen with surprise.<br />

“You came before me last year with this ill-formed notion of a forensics unit,” she said.<br />

“Requesting funds for a science that my advisors assured me was hardly a science at all… and yet I<br />

personally financed you. Since that date your unit has provided service beyond reproach, proving that<br />

my support of your work was not in vain. But do you imagine I would have invested so much in an<br />

ordinary detective named Trevor Welles without a bit of intelligence of my own? I would venture I<br />

know as much about you as your own mother does. Your mother who, if memory serves, is named<br />

Edith and resides in Shropshire. A lovely piece of country, albeit a bit remote.”

Trevor could think of nothing to say to any of this, which was just as well, since the<br />

Queen continued. “So I am quite aware of your friendship with Miss Bainbridge, a woman I met<br />

years ago. I gather that she also made acquaintance with Anthony Weaver in her girlhood?”<br />

At least she had dropped the “we,” and, in fact, was looking at him with sympathetic<br />

interest, but Trevor was unsure of how much of Geraldine’s story he should share with the Queen.<br />

“Not exactly girlhood,” he said, aware that he was avoiding the key issue. “Miss<br />

Bainbridge was thirty-five.”<br />

“And this strikes you as an age too advanced for romantic intrigue? How old are you,<br />

Detective?”<br />

“Thirty-four,” he admitted.<br />

“Then you must hurry. The clock is surely about to strike.”<br />

Was she making a joke? Trevor had never known the Queen to joke.<br />

“Geraldine traveled to India in 1856, the year before Roland Everlee’s death,” he finally<br />

said. When in doubt, best to stick to the barest of facts. “Rose Everlee was her chaperone for the<br />

voyage and introduced her to Anthony Weaver on the ship, during the weeks that they were in transit<br />

between London and Bombay.”<br />

It was an incomplete explanation, to be sure, but the Queen seemed to grasp the<br />

implications behind his words at once. She nodded briskly and reached for a paper on the table<br />

beside her. It bore a grand blob of maroon-colored sealing wax on the back, a detail which struck<br />

Trevor as odd.<br />

“It is quite fascinating how matters sometimes converge,” she said. “For I received just<br />

this morning a letter from Michael Everlee on this same subject. Do you know the man?”<br />

“Only by reputation,” Trevor said.<br />

“Indeed,” said the Queen. “Cambridge educated, the young hero of the Conservative<br />

Party and thus a rising figure in the House of Commons. Or so they tell me.” Peering down, she read<br />

aloud:<br />

Your Majesty:<br />

I turn to you in humble request. My stepfather, the retired Secretary-General Anthony Weaver,<br />

has been unjustly arrested for the murder of my mother, Rose Everlee Weaver. Your majesty knows<br />

the details of my true father’s death. Mr. Weaver married my mother shortly after my birth, and he<br />

is the only man I have ever known as a father. A finer or more honorable man could not be found<br />

and thus I know he could not be guilty of such a crime.<br />

I am traveling to India at once and shall be in route to Bombay by the time you read this. I am<br />

humbly writing to ask that you encourage the local authorities to welcome my intrusion into this<br />

matter and to assist me as I endeavor to prove my stepfather’s innocence.<br />

With deepest humility,<br />

Michael Everlee<br />

The Queen folded the letter. “What do you make of that?”<br />

Trevor's first thought was that any man who claimed to be humble three times in a row<br />

was probably anything but, and that nothing in the graceless phrasing of the letter suggested that the<br />

author was a Cambridge man, much less a rising star in political circles. But presumably the poor<br />

chap was in shock over recent events and, just as he said, rushing to pack and travel. So instead of<br />

critiquing the tone of the writing, Trevor took a different tack.

“The letter was obviously composed in haste,” he said cautiously. “And yet I am struck<br />

by what it does not say.”<br />

“No mention of grief for his mother,” the Queen said.<br />

“Indeed,” said Trevor. “And no insistence that justice should be done on her behalf. His<br />

only concern is freeing the stepfather, but even his defense of Mr. Weaver is rather oddly stated.”<br />

The Queen slowly nodded. “He does not say that Anthony Weaver would not have killed<br />

his wife because he loved her. Instead he suggests this would be impossible only because Mr.<br />

Weaver is an honorable man.”<br />

One motion Trevor had never seen the Queen make was a shrug; as the dominant<br />

monarch of the civilized world, it would never do for Victoria to show either indifference or<br />

uncertainty. And yet she came close to the gesture now, her shoulders rising and dropping ever so<br />

slightly. “I was not touched by this letter in the least, Detective,” she said. “The line about him<br />

trusting that I remember the details of his true father’s death was nothing more than a bully of the most<br />

direct sort. He all but said that his father was a decorated hero and thus that I must help him. I do not<br />

like to have my hand forced in such a manner.”<br />

Now she did shrug. “The trouble, of course, is that his father was a decorated hero and<br />

thus I indeed must help him. I was about to compose a directive to the Bombay police this afternoon,<br />

but put the matter aside to grant you an audience. And now it strikes me that this seeming coincidence<br />

is not coincidence at all, but rather an indication that the Weaver murder has more wide-ranging<br />

significance than I originally understood.”<br />

The Queen paused. “I recall Miss Bainbridge’s unique personality most specifically,”<br />

she softly added. “I can only assume that she too plans to depart for Bombay?”<br />

“I imagine that she is packing now, your Majesty.”<br />

“Do you further imagine that our Miss Kelly and the charming young doctor will<br />

accompany her?”<br />

“Yes, Emma is Geraldine’s companion and Tom is her nephew so I feel safe in<br />

predicting that they are packing as well.”<br />

“And so shall you,” said the Queen.<br />

Even though Trevor had come to Windsor with just this intent, the swiftness of the<br />

Queen’s decision stunned him. “You wish me to go to India, Your Majesty?”<br />

“Yes, and take the others. The clever Jew and that young bobby who looks like a<br />

choirboy. The report from Bombay was sadly limited, so it is impossible to predict what you will<br />

find when you arrive there, but something about all this is…it seems very queer, Detective. I shall<br />

write precisely the directive that Michael Everlee requested, but on your behalf. Informing the local<br />

authorities that your team will be conducting an independent investigation at my special request and<br />

instructing them to grant you every courtesy in your efforts.”<br />

And won’t they just love that, Trevor thought. The one thing the Everlee pup had gotten<br />

right was when he called British interest in an Indian crime “an intrusion.” But Trevor nodded to the<br />

Queen and, following her wave of dismissal, rose to his feet.<br />

“Speed is essential, Detective,” Victoria said. “I doubt you shall be able to overtake<br />

Michael Everlee in his journey, but with any luck you shall join him in Bombay before he manages to<br />

do any real damage.”<br />

“Damage to the case, Your Majesty?”<br />

“Damage to the crown.” The Queen looked at the letter on the table beside her with<br />

distaste. “We do not trust him.”

Chapter Four<br />

The Port of Suez<br />

August 21, 1889<br />

10:15 AM<br />

Whenever the Queen of England takes an interest, matters begin to move with astonishing<br />

speed.<br />

Within hours of Trevor’s audience at Windsor Castle, paperwork had been delivered to<br />

his quarters in the rooming house, detailing travel plans for six people, and by the next afternoon, they<br />

were all on the train. The morning of the third day found them at the port of Suez, preparing to board<br />

a steamer for Bombay.<br />

As the rest of the group went strolling, determined to absorb the limited charms a<br />

working port has to offer and taking advantage of their brief respite between the train and the boat,<br />

Trevor remained behind. He found a bit of shade on the dock and leaned back against a wall of<br />

cargo, keeping an eye on the group’s trunks and valises as he waited. Trevor had spent his<br />

professional lifetime struggling to surmount the British mistrust of foreigners – a form of bigotry that<br />

he knew, despite his concerted attempts to dispel it, still flowed within his veins. From the moment of<br />

their arrival, this Arab port had struck him as utter mayhem, with any number of small, dark men<br />

darting about beneath the relentless Middle Eastern sun, babbling among themselves in an<br />

incomprehensible tongue.<br />

Take this fellow, for example. He was approaching the heap of eleven bags, all piled<br />

into a rough crate, which had accompanied them so far on their trip. One for each man, two for<br />

Emma, and the remaining five crammed with any number of improbable items which Geraldine had<br />

solemnly declared to be “necessities.” Judging from the shape, one of them apparently held a violin.<br />

Trevor did not wish to insult the dockworker, who moved about the cargo with the agility of a boy<br />

and the face of a grandfather, but he could hardly help but stare when the man pulled from his pocket,<br />

of all things, a paintbrush. Dipping it into a nearby can of black paint, he marked the side of the crate<br />

with four English letters: POSH.<br />

“Never thought I’d see the day when the likes of us would be called posh, did you, Sir?”<br />

Trevor tilted his chin in the direction of the familiar voice. “You decided to cut your<br />

walk short, Davy?”<br />

“Not exactly a stroll through Covent Garden, is it, Sir?”<br />

“That it is not,” Trevor agreed, reflecting that it was probably nerves about boarding the<br />

ship as much as the smell and clutter of the port which had driven the boy back. It was well known<br />

throughout the group that Davy suffered from seasickness.<br />

“We won’t be on the open sea for long, lad,” Trevor went on, his eyes never leaving the<br />

man with the paintbrush, who had now moved to mark the same four letters on the other side of the<br />

crate. “We’ll be sailing a strait with land in view on both sides for at least half the journey.”<br />

“I know, Sir,” Davy said, although he hardly sounded convinced. “Miss Emma showed<br />

me the map.”<br />

“And you know what this means?” Trevor asked, gesturing toward the crate with his<br />

pipe. “This POSH?”<br />

“Stands for Port Out, Starboard Home,” Davy said promptly. “So we’re to be in the best

cabins, both coming and going, which means those located on the shaded side of the ship. Although<br />

whether we’re to thank the Queen or Miss Bainbridge for our favored position, I can’t say, Sir. Can<br />

you?”<br />

“Probably Gerry,” Trevor said. “She seems to have a knack for plucking out small<br />

strands of luxury, even in the most ghastly of circumstances.” It was barely past ten in the morning<br />

and the heat on the dock was already oppressive. Trevor could scarcely bear to think what it would<br />

be like in the early afternoon, with the sun directly overhead. A shaded stateroom would be worth<br />

rubies in such a situation. Trevor had heard of the term “posh,” of course, but had never known the<br />

precise derivation of the word, or that it was meant to describe those who could afford to travel even<br />

the tropics in relative comfort. He sent up a silent prayer of thanksgiving, hardly his first, for the fact<br />

Geraldine was both rich and generous. In the future he would oversee her five bags with less<br />

complaint.<br />

“But you know what I don’t understand, Sir?” Davy asked.<br />

“I cannot imagine, for you seem to understand a great deal, Davy. Often more than<br />

Rayley and myself combined, I should venture.”<br />

The boy flushed with pleasure. Or perhaps he was simply flushed. Hard to tell in this<br />

heat, and Trevor made a mental note that once they were finally in Bombay he must shuck these<br />

purgatorial tweeds and purchase himself a white linen suit. He had always considered such garments<br />

the height of ostentation – practically a shout to the world that one was well-traveled – but he was<br />

already beginning to see their usefulness.<br />

“The Indian manservant?” Davy said. “The one who was killed with the old lady?<br />

Didn’t the report say he’d been her servant nearly the whole length of time she’d been in India?”<br />

“It did indeed. Years upon years in her service.”<br />

“So how old was the fellow?”<br />

Trevor sighed. “Gone past seventy, just like his mistress. I know where you’re heading<br />

with this and I quite agree. Keeping such an elderly man as a bodyguard is a ridiculous notion, even<br />

though the report says this quite pointedly. Pulkit Sang was not a porter or a butler, but the bodyguard<br />

of Rose Everlee Weaver. We can only assume that the position was a bit of an honorarium. A way for<br />

a trusted servant of long standing to keep his hand in the game, retaining the title more than the duties.<br />

I can’t imagine a woman like Mrs. Weaver would need much protection, can you?”<br />

“And yet she was murdered,” Davy said matter-of-factly.<br />

“And yet,” Trevor admitted. “You obviously have a thought, so by all means, state it<br />

cleanly.”<br />

“This woman was the wife of a retired Secretary-General,” Davy said. “Living in<br />

comfort in a big home in Bombay. Probably all she had to do all day was ride back and forth to her<br />

social club. What did the report call it?”<br />

“The Byculla Club,” Trevor said. “Apparently the hub of all British activity in the city.<br />

Are you asking why such a woman would need a bodyguard?”<br />

Davy shook his head and the two men stood back to allow a contingent of the Arab<br />

porters to surround the ponderous crate which held their bags. Lifting it to their shoulders, much like<br />

pallbearers with a coffin, they proceeded toward the gangplank.<br />

“I think you’re on to it, Sir. That the reason she had a bodyguard now was because she<br />

didn’t want to sack an old man who’d been in service to her for so many years. I guess what I am<br />

wondering is why she would have needed a bodyguard in the first place. All those years ago, when<br />

the lady first hired the fellow, what was she afraid of?”

Trevor looked at Davy in surprise. “You are quite right, Davy, of course you are.<br />

Perhaps her husband – either the first or the second, who can say – insisted she take on protection. I<br />

would imagine that many of the British did so in the years surrounding the mutiny of ‘57, when fears<br />

were running high. Who knows, as the widow of one high-ranking officer and then the wife of<br />

another, she might have been a likely target for kidnapping or some other form of extortion. I shall<br />

check when we arrive and see if any specific threat might have been made, long ago, that convinced<br />

Rose or someone close to her that she needed a bodyguard.”<br />

“And Sir?” Davy ventured.<br />

“Yes, lad?”<br />

“While you are asking, try to find out why the lady would have chosen an Indian<br />

bodyguard. Seems more probable, under the circumstances, that she’d have wanted British.”<br />

***<br />

Bombay - The Terrace of the Byculla Club<br />

1:49 AM<br />

“To be honest,” Hubert Morass said, tossing back the last of his gin and tonic, “I struggle<br />

to understand why the death of an old lady and her servant should cause so much excitement.”<br />

“Is that so?” Henry Seal asked drily, gazing into his own glass. Gin and tonics were the<br />

drink of choice among the elite of the Raj, and the cocktail was claimed to be popular for its<br />

medicinal value. The tonic water was dosed with quinine to offset the chance of malaria and the<br />