BCJ_WINTER17 Digital Edition

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

OPINION<br />

IS WILDLIFE VIEWING THE NEW HUNTING?<br />

BY EDWARD PUTNAM<br />

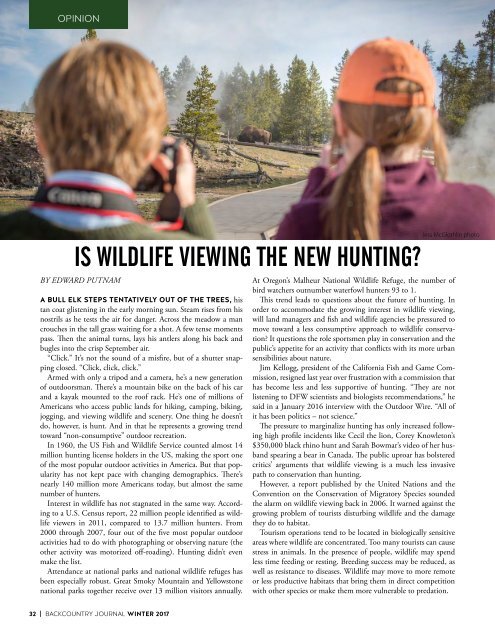

A BULL ELK STEPS TENTATIVELY OUT OF THE TREES, his<br />

tan coat glistening in the early morning sun. Steam rises from his<br />

nostrils as he tests the air for danger. Across the meadow a man<br />

crouches in the tall grass waiting for a shot. A few tense moments<br />

pass. Then the animal turns, lays his antlers along his back and<br />

bugles into the crisp September air.<br />

“Click.” It’s not the sound of a misfire, but of a shutter snapping<br />

closed. “Click, click, click.”<br />

Armed with only a tripod and a camera, he’s a new generation<br />

of outdoorsman. There’s a mountain bike on the back of his car<br />

and a kayak mounted to the roof rack. He’s one of millions of<br />

Americans who access public lands for hiking, camping, biking,<br />

jogging, and viewing wildlife and scenery. One thing he doesn’t<br />

do, however, is hunt. And in that he represents a growing trend<br />

toward “non-consumptive” outdoor recreation.<br />

In 1960, the US Fish and Wildlife Service counted almost 14<br />

million hunting license holders in the US, making the sport one<br />

of the most popular outdoor activities in America. But that popularity<br />

has not kept pace with changing demographics. There’s<br />

nearly 140 million more Americans today, but almost the same<br />

number of hunters.<br />

Interest in wildlife has not stagnated in the same way. According<br />

to a U.S. Census report, 22 million people identified as wildlife<br />

viewers in 2011, compared to 13.7 million hunters. From<br />

2000 through 2007, four out of the five most popular outdoor<br />

activities had to do with photographing or observing nature (the<br />

other activity was motorized off-roading). Hunting didn’t even<br />

make the list.<br />

Attendance at national parks and national wildlife refuges has<br />

been especially robust. Great Smoky Mountain and Yellowstone<br />

national parks together receive over 13 million visitors annually.<br />

Jess McGlothlin photo<br />

At Oregon’s Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, the number of<br />

bird watchers outnumber waterfowl hunters 93 to 1.<br />

This trend leads to questions about the future of hunting. In<br />

order to accommodate the growing interest in wildlife viewing,<br />

will land managers and fish and wildlife agencies be pressured to<br />

move toward a less consumptive approach to wildlife conservation?<br />

It questions the role sportsmen play in conservation and the<br />

public’s appetite for an activity that conflicts with its more urban<br />

sensibilities about nature.<br />

Jim Kellogg, president of the California Fish and Game Commission,<br />

resigned last year over frustration with a commission that<br />

has become less and less supportive of hunting. “They are not<br />

listening to DFW scientists and biologists recommendations,” he<br />

said in a January 2016 interview with the Outdoor Wire. “All of<br />

it has been politics – not science.”<br />

The pressure to marginalize hunting has only increased following<br />

high profile incidents like Cecil the lion, Corey Knowleton’s<br />

$350,000 black rhino hunt and Sarah Bowmar’s video of her husband<br />

spearing a bear in Canada. The public uproar has bolstered<br />

critics’ arguments that wildlife viewing is a much less invasive<br />

path to conservation than hunting.<br />

However, a report published by the United Nations and the<br />

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species sounded<br />

the alarm on wildlife viewing back in 2006. It warned against the<br />

growing problem of tourists disturbing wildlife and the damage<br />

they do to habitat.<br />

Tourism operations tend to be located in biologically sensitive<br />

areas where wildlife are concentrated. Too many tourists can cause<br />

stress in animals. In the presence of people, wildlife may spend<br />

less time feeding or resting. Breeding success may be reduced, as<br />

well as resistance to diseases. Wildlife may move to more remote<br />

or less productive habitats that bring them in direct competition<br />

with other species or make them more vulnerable to predation.<br />

Tourism operations also require roads, facilities and other infrastructure<br />

that can place a burden on habitat. Fragmentation<br />

that impedes migration can cause populations to become isolated,<br />

thereby reducing their genetic diversity over time.<br />

Crowding, pollution, garbage and sewage are ongoing challenges<br />

of regulating tourism. Yellowstone National Park, for example,<br />

requires approximately 780 staff to manage its 4 million annual<br />

visitors. Those crowds provide a crucial economic boost to surrounding<br />

communities, which helps support the park’s existence.<br />

However, according to the park’s own business plan, it doesn’t<br />

generate sufficient revenue to cover its operating budget, let alone<br />

its wildlife management obligations. Instead it relies on federal<br />

appropriations for the bulk of its conservation funding.<br />

That gap between boots-on-the-ground conservation and the<br />

wallets of tourists presents a budgetary challenge to wildlife agencies.<br />

Most wild public lands are not managed for tourism and<br />

don’t have the broad appeal that Yellowstone and Grand Teton<br />

national parks have, yet they are equally in need of money for<br />

fish and wildlife. Even if tourism could generate enough revenue,<br />

relying on Congress or state legislatures to appropriate it wisely<br />

seems wildly optimistic.<br />

The Land and Water Conservation Fund, for example, is supposed<br />

to receive $900 million annually from oil and gas leases.<br />

How many times has that happened in its 50-year history? Only<br />

once. Large portions of that money are usually siphoned off for<br />

other purposes that have nothing to do with conservation. And<br />

Congress isn’t likely to have a change of heart any time soon. In<br />

2015 it nearly killed the program altogether. That kind of uncertainty<br />

doesn’t lend itself to a sound, long term conservation<br />

strategy.<br />

The budget challenge underscores the essential difference between<br />

hunting and other forms of outdoor recreation. The money<br />

sportsmen spend on licenses and tags goes to fund the bulk of<br />

state fish and wildlife agencies’ budgets. Excise taxes on hunting<br />

equipment, firearms and ammunition contribute millions annually<br />

as well. In these ways, hunters contribute to conservation directly<br />

and distribute conservation funding over a wide geographic<br />

area rather than on a few high profile locales.<br />

The agencies use the money to develop wildlife management<br />

plans with specific objectives, goals and strategies. They develop<br />

programs, perform field surveys and improve habitat. They study<br />

wildlife behavior, migration patterns, human impacts, diseases,<br />

invasive species, etc. that make it possible for wildlife to flourish<br />

in the face of an expanding human population. They enforce<br />

game laws, respond to human/wildlife conflicts, engage in public<br />

education and help provide opportunities for the public to participate<br />

in the outdoors. In short, the “sport” of hunting isn’t just a<br />

contributor to conservation, it’s an integral part of it in a way that<br />

other forms of outdoor recreation are not.<br />

Hunting allows us to fill the niche our hunter/gatherer ancestors<br />

once occupied. When well regulated, the presence of hunters<br />

on the landscape has a positive impact that goes beyond just<br />

managing animal populations. It helps keep wild animals from<br />

becoming habituated to people, which reduces the potential for<br />

conflict. It affects their habits and behavior, which has a trophic<br />

influence throughout ecosystems that helps bolster diversity. It<br />

keeps animals wary and vigilant, improving the chances of survival<br />

for those that are, and removing those that aren’t from the<br />

gene pool.<br />

In his book Going Wild: Hunting, Animal Rights and the Contested<br />

Meaning of Nature, Jan Dizzard details the sometimes contentious<br />

issue of hunting versus wildlife viewing. The showdown<br />

was in the Quabbin Watershed in central Massachusetts. A 50-<br />

year ban on hunting there had produced a large and approachable<br />

deer population estimated at between 20 and 50 animals per<br />

square mile. For many it was a kind of Eden, a pristine wilderness<br />

where humans and wildlife could coexist in peace. The deer, however<br />

were quickly eating their way through the hardwood forest,<br />

jeopardizing the health of the watershed. Alternatives to hunting<br />

were considered but deemed impractical.<br />

So in 1991 over a storm of protest, an annual controlled deer<br />

hunt was established as the best and most cost effective approach<br />

to management. The success was stunning. Within a few short<br />

years the deer population came down to a sustainable level and<br />

the forest recovered. Today the Quabbin supports a healthy deer<br />

population of approximately 15-20 per square mile. They’re wild,<br />

meaning they behave like wild animals, and because the hunt is<br />

regulated, only a small percentage of hunters are successful, ensuring<br />

the continued health of the species and its habitat.<br />

It’s a myth that by not hunting a person does no harm to wildlife.<br />

By far, the greatest threat to wildlife today is habitat loss,<br />

and by embracing the values of an industrialized society we are<br />

all culpable. Expanding urban boundaries, fragmenting habitat,<br />

diverting water for agriculture, sacrificing wildness for more out-<br />

Nick Trehearne photo<br />

32 | BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL WINTER 2017 WINTER 2017 BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 33