BCJ_SPRING 17 Digital Edition

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

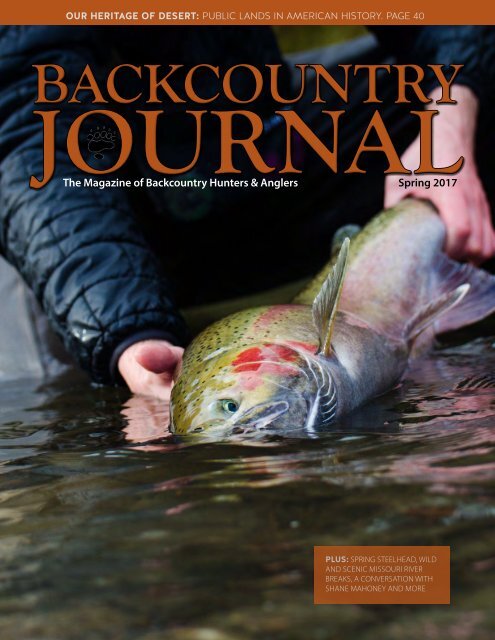

OUR HERITAGE OF DESERT: PUBLIC LANDS IN AMERICAN HISTORY. PAGE 40<br />

BACKCOUNTRY<br />

JOURNAL<br />

The Magazine of Backcountry Hunters & Anglers Spring 20<strong>17</strong><br />

PLUS: <strong>SPRING</strong> STEELHEAD, WILD<br />

AND SCENIC MISSOURI RIVER<br />

BREAKS, A CONVERSATION WITH<br />

SHANE MAHONEY AND MORE

PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE<br />

IN THE ARENA<br />

HUNTING MAPS FOR EVERY DEVICE<br />

#HUNTSMARTER<br />

WITH THE NEW ERA OF GPS<br />

Search onXmaps<br />

View maps online at huntinggpsmaps.com/web<br />

ONE OF MY FAVORITE QUOTES comes<br />

from Theodore Roosevelt. The year was<br />

1910, and Roosevelt was contemplating<br />

coming out of retirement and running for<br />

president again. He was disappointed in<br />

how his hand-picked successor, William<br />

Howard Taft, was dismantling his legacy.<br />

Not one to sit idle, he re-entered the fray<br />

and formed the Bull Moose Party.<br />

Roosevelt’s willingness to think altruistically<br />

and actually do, rather than just talk,<br />

mirrors our ethos here at BHA. For those<br />

who don’t know that quote:<br />

It is not the critic who counts; not the man<br />

who points out how the strong man stumbles,<br />

or where the doer of deeds could have<br />

done them better. The credit belongs to the<br />

man who is actually in the arena, whose<br />

face is marred by dust and sweat and blood;<br />

who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes<br />

short again and again, because there is no<br />

effort without error and shortcoming; but<br />

who does actually strive to do the deeds;<br />

who knows great enthusiasms, the great<br />

devotions; who spends himself in a worthy<br />

cause; who at the best knows in the end the<br />

triumph of high achievement, and who at<br />

the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring<br />

greatly, so that his place shall never be<br />

with those cold and timid souls who neither<br />

know victory nor defeat.<br />

Every time I read these words I can hear<br />

his voice and see him shake his fists as he issues<br />

his greatest call to arms. What I would<br />

do to have another politician like T.R.!<br />

Alas, I’m not holding my breath. Instead,<br />

just like T.R., we here at BHA are charging<br />

forward. Our ranks are swelling. Membership<br />

numbers have almost quadrupled from<br />

a year ago. Chapters continue to increase in<br />

number, leadership and clout. Our growing<br />

staff is providing expertise to help amplify<br />

the voices of our boots on the ground, all<br />

across North America.<br />

I couldn’t be more proud of our members.<br />

In particular, the work you all did to<br />

convince Rep. Jason Chaffetz to pull his<br />

support of H.R. 621, the Disposal of Excess<br />

Federal Lands Act of 20<strong>17</strong>, was nothing<br />

short of phenomenal.<br />

In <strong>17</strong> years working on sportsmen’s<br />

policy issues, I have never seen a member<br />

of Congress abandon a bill he or she had<br />

introduced a week before. Never. Our ire<br />

was swift and unapologetic. We the people<br />

made it clear that we would not tolerate the<br />

wholesale disposal of our public lands, in<br />

this case, 3 million-plus acres in 11 Western<br />

states.<br />

Our opposition came in the form of<br />

phone calls, emails, social media posts<br />

and appearances at the congressman’s own<br />

town hall meeting. It was unrelenting. And<br />

it achieved results. Just like democracy is<br />

supposed to work, our voices made him<br />

listen. Rep. Chaffetz shouldn’t have introduced<br />

H.R. 621 in the first place, but he<br />

did, and this exercise should give notice to<br />

any other politicians foolish enough to take<br />

us on. Public lands are our second Second<br />

Amendment, and we won’t be silent as the<br />

modern-day robber barons try to steal them<br />

from us. From above, Roosevelt has to be<br />

flashing that big ol’ Cheshire Cat grin – all<br />

the while urging us forward.<br />

While we should revel in the demise of<br />

the Chaffetz bill, that was just one skirmish.<br />

The war is far from over. On the<br />

horizon emerge new attempts to wrest away<br />

our public lands and waters, as well as attacks<br />

on clean water, the Land and Water<br />

Conservation Fund, conservation of wildlife-rich<br />

landscapes like the Western sagebrush<br />

steppe, and funding for the agencies<br />

that hold the key to the future of our fish<br />

and wildlife and hunting and fishing traditions.<br />

Our backs are strong, we are determined,<br />

and we are ready to fight. Rest assured,<br />

BHA will be in the arena for each and every<br />

battle for our lands and waters, our public<br />

access opportunities, and our invaluable<br />

outdoors heritage. Victory might be hard<br />

won, but I have faith in our members, volunteers<br />

and partners to give it everything<br />

we’ve got. To do otherwise just ain’t in our<br />

nature.<br />

For those of you traveling to Missoula<br />

for BHA’s North American Rendezvous in<br />

April, I can’t wait to give you a high five,<br />

swap some stories, and plot and scheme<br />

into the wee hours how we can protect our<br />

great legacy. For those who can’t make it, we<br />

know you will be there in spirit and we will<br />

raise our glasses in your honor. Our army<br />

is building, and we will not be denied.<br />

Land derives much of his inspiration – and humor – from<br />

Theodore Roosevelt, our greatest conservationist president.<br />

Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.<br />

Onward and Upward,<br />

Land Tawney<br />

President & CEO<br />

<strong>SPRING</strong> 20<strong>17</strong> BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 3

YOUR BACKCOUNTRY<br />

WHAT IS BHA?<br />

BACKCOUNTRY HUNTERS & ANGLERS<br />

is a North American conservation<br />

nonprofit 501(c)(3) dedicated to the<br />

conservation of backcountry fish and<br />

wildlife habitat, sustaining and expanding<br />

access to important lands and waters, and<br />

upholding the principles of fair chase.<br />

This is our quarterly magazine. We fight to<br />

maintain and enhance the backcountry<br />

values that define our passions: challenge,<br />

solitude and beauty. Join us. Become<br />

part of the sportsmen’s voice for our wild<br />

public lands, waters and wildlife.<br />

Sign up at www.backcountryhunters.org.<br />

STATE CHAPTERS<br />

BHA HAS MEMBERS across the<br />

continent, with chapters representing 25<br />

states and provinces. Grassroots public<br />

lands sportsmen and women are the<br />

driving force behind BHA. Learn more<br />

about what BHA is doing in your state on<br />

page 26. If you are looking for ways to get<br />

involved, email your state chapter chair at<br />

the following addresses:<br />

• alaska@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• arizona@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• britishcolumbia@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• california@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• colorado@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• idaho@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• michigan@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• minnesota@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• montana@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• nevada@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• newengland@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• newmexico@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• newyork@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• oregon@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• pennsylvania@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• texas@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• utah@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• washington@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• wisconsin@backcountryhunters.org<br />

• wyoming@backcountryhunters.org<br />

THE SPORTSMEN’S VOICE FOR OUR WILD PUBLIC LANDS, WATERS AND WILDLIFE<br />

Ryan Busse (Montana) Chairman<br />

Jay Banta (Utah)<br />

Heather Kelly (Alaska)<br />

T. Edward Nickens (North Carolina)<br />

Rachel Vandevoort (Montana)<br />

Michael Beagle (Oregon) President Emeritus<br />

President & CEO<br />

Land Tawney, tawney@backcountryhunters.org<br />

Southwest Chapter Coordinator<br />

Jason Amaro, jason@backcountryhunters.org<br />

Campus Outreach Coordinator<br />

Sawyer Connelly, sawyer@backcountryhunters.org<br />

Office Manager<br />

Caitlin Frisbie, frisbie@backcountryhunters.org<br />

Great Lakes Coordinator<br />

Will Jenkins, will@thewilltohunt.com<br />

Central Idaho Coordinator<br />

Mike McConnell, whiteh2omac@gmail.com<br />

Operations Director<br />

Frankie McBurney Olson, frankie@backcountryhunters.org<br />

Social Media and Online Advocacy Coordinator<br />

Nicole Qualtieri, nicole@backcountryhunters.org<br />

Chapter Coordinator<br />

Ty Stubblefield, ty@backcountryhunters.org<br />

JOURNAL CONTRIBUTORS<br />

Jesse Alston, Edward Anderson, Bendrix Bailey, Matt<br />

Breton, Sawyer Connelly, Allie D’Andrea, Michael<br />

Furtman, T.J. Hauge, Bryan Huskey, Michael Lein, Mike<br />

McConnell, Kris Millgate, Jeff Mishler, Katie Morrison,<br />

Eric Nuse, Nicole Qualtieri, Tim Romano, Dale Spartas,<br />

E. Donnall Thomas Jr., Lori Thomas, Alec Underwood,<br />

Louis S. Warren, J.R. Young, Isaac Zarecki<br />

Cover photo: Sam Lungren, Washington Steelhead<br />

Backcountry Journal is the quarterly membership<br />

publication of Backcountry Hunters & Anglers. All<br />

rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in any<br />

manner without the consent of the publisher. Writing<br />

and photography queries, submissions and advertising<br />

questions contact sam@backcountryhunters.org<br />

Published Spring 20<strong>17</strong>. Volume XII, Issue II<br />

BHA HEADQUARTERS<br />

P.O. Box 9257, Missoula, MT 59807<br />

www.backcountryhunters.org<br />

admin@backcountryhunters.org<br />

(406) 926-1908<br />

BOARD OF DIRECTORS<br />

STAFF<br />

Sean Carriere (Idaho) Treasurer<br />

Ben Bulis (Montana)<br />

Ted Koch (New Mexico)<br />

Mike Schoby (Montana)<br />

J.R. Young (California)<br />

Joel Webster (Montana) Chairman Emeritus<br />

Donor and Corporate Relations Manager<br />

Grant Alban, grant@backcountryhunters.org<br />

State Policy Director<br />

Tim Brass, tim@backcountryhunters.org<br />

Conservation Director<br />

John Gale, gale@backcountryhunters.org<br />

Montana Chapter Coordinator<br />

Jeff Lukas, jeff@bakcountryhunters.org<br />

Backcountry Journal Editor<br />

Sam Lungren, sam@backcountryhunters.org<br />

Communications Director<br />

Katie McKalip, mckalip@backcountryhunters.org<br />

Northwest Outreach Coordinator<br />

Jesse Salsberry, jesse@crowfly.cc<br />

Membership Coordinator<br />

Ryan Silcox, ryan@backcountryhunters.org<br />

Interns: Trey Curtiss, Alex Kim, Liam Rossier,<br />

Ty Smail, Isaac Zarecki<br />

BHA LEGACY PARTNERS<br />

The following Legacy Partners have committed<br />

$1000 or more to BHA for the next three years. To<br />

find out how you can become a Legacy Partner,<br />

please contact grant@backcountryhunters.org.<br />

Bendrix Bailey, Mike Beagle, Cidney Brown, Dave<br />

Cline, Todd DeBonis, Dan Edwards, Blake Fischer,<br />

Whit Fosburgh, Stephen Graf, Ryan Huckeby,<br />

Richard Kacin, Ted Koch, Peter Lupsha, Robert<br />

Magill, Chol McGlynn, Nick Miller, Nick Nichols,<br />

John Pollard, William Rahr, Adam Ratner, Robert<br />

Tammen, Karl Van Calcar, Michael Verville, Barry<br />

Whitehill, J.R. Young, Dr. Renee Young<br />

JOIN THE CONVERSATION<br />

facebook.com/backcountryhabitat<br />

plus.google.com/+BackcountryHuntersAnglers<br />

twitter.com/Backcountry_H_A<br />

youtube.com/BackcountryHunters1<br />

instagram.com/backcountryhunters<br />

Katie Morrison photo<br />

BIGHORN WILDLAND PROVINCIAL PARK, ALBERTA<br />

BY KATIE MORRISON<br />

IN MY EARLY 20S, I WENT PADDLING with my dad on the<br />

North Saskatchewan River just east of the Bighorn Wildland of<br />

Alberta. Dad introduced me to fishing at a young age, and time<br />

on the water with him helped keep us close even as I grew up and<br />

spent more time away from home. Unfortunately, this trip was<br />

one of the last we would take together. He passed away a couple<br />

of years later, but in that moment I remember feeling as far away<br />

from civilization as one could get – just two of us alone with the<br />

river and the fish.<br />

A few years ago a friend and I paddled the same section of the<br />

river, expecting to feel the same quiet connection to place. But<br />

this time it was a completely different experience. Hardly an hour<br />

went by that we did not hear the thrum of motorized vehicles or<br />

the splash of trucks driving into the river or see the light of flare<br />

stacks on the horizon. The wild place I had escaped to 15 years<br />

earlier was gone. These are the changes pushing farther into Alberta’s<br />

foothills, chasing backcountry users into fewer and smaller<br />

quiet places.<br />

Last year I went farther west and deeper into the Bighorn,<br />

searching out this missing solitude. The sun broke through the<br />

clouds just as we reached our alpine destination. Our little group<br />

had spent the day carting packs and gear under drizzling skies to<br />

reach Lake of the Falls in the heart of the Bighorn backcountry. At<br />

first glance it looked like we had the turquoise lake to ourselves,<br />

but as we drew near a couple of other anglers appeared on the far<br />

side of the lake, their lures hitting the water with light splashes.<br />

The sun was now warm on our faces, and the clear, trout-filled<br />

water sparkled against the scree slopes before diving downstream<br />

to gurgle its way through a series of braided creeks.<br />

As we found our spot on the lake, I realized that something was<br />

missing that made this Alberta experience different from exploring<br />

so many other areas on the front range of the Northern Rocky<br />

Mountains. The constant drone of off-highway vehicles and industrial<br />

activity was conspicuously absent. It is this absence as<br />

much as the abundance of trout, birds, elk, grizzly bears, cougars<br />

and bighorn sheep, that make the Bighorn such a draw for backcountry<br />

enthusiasts.<br />

The Bighorn Wildland is among Alberta’s last wild places. Like<br />

the missing piece of a jigsaw puzzle between Banff and Jasper<br />

National Parks and nestled against the White Goat and Siffleur<br />

Wilderness Areas, the 1.25-million-acre Bighorn area is one of the<br />

few relatively intact, roadless areas that remain in Alberta.<br />

Its forests, rivers and streams are the headwaters for the North<br />

Saskatchewan River, supplying the vast majority of clean water<br />

to central Alberta communities, including the capital city of Edmonton.<br />

But it is the escape from the city and from the constant<br />

noise and scars on so many other public lands that makes this<br />

place so special. Just mentioning the Bighorn to Albertan hunters<br />

will often invoke stories of elk hunts and the trophy rams to<br />

which the Bighorn owes its name.<br />

But even this is changing. I recently had a conversation with<br />

Alberta BHA member Kevin Van Tighem, who has been hunting<br />

the front range of the Rockies for decades. He told me of hunting<br />

sheep in Job Creek in the ’80s and how his party got two rams one<br />

year. It was classic wilderness sheep hunting, packing in by horse<br />

over Cline Pass and camping in wall tents. “Even then, off-roaders<br />

were just starting to sneak in from the Brazeau side,” Kevin<br />

said. “I don’t know what it’s like now, but I suspect it’s a gong<br />

show as I seem to recall the government officially allowed quad<br />

access a few years later.”<br />

Although parts of the Bighorn are quiet and wild, much of the<br />

rest of the area is open to off-highway vehicle use. It also is facing<br />

threats from industrial activities such as logging, oil and gas<br />

development, and open-pit coal mines, which are creeping into<br />

previously undisturbed lands, dirtying municipal watersheds and<br />

pushing the wild farther and farther back.<br />

It is because of these changes and the future they foreshadow<br />

that conservation organizations, hiking groups, local community<br />

members, guides and passionate hunters and anglers are trying to<br />

protect this iconic area while working to find more appropriate<br />

places for controlled motorized use.<br />

Thirty years ago, the Alberta government promised permanent<br />

protection for the Bighorn in its Eastern Slopes Policy, a promise<br />

which has yet to be fulfilled.<br />

The soon to be formed Alberta Chapter of Backcountry Hunters<br />

& Anglers is the most recent group to join the call for protection<br />

of the Bighorn as a wildland provincial park, a designation<br />

that will protect nature and wilderness values while providing unparalleled<br />

hunting and fishing opportunities.<br />

The Alberta government has committed to expanding our protected<br />

areas system, and after so many years of waiting, the Bighorn<br />

is an obvious next step. They will need the support of all<br />

Albertans, but especially those of us who know the power of these<br />

wild places to connect us to the land, to our wild heritage, and to<br />

each other.<br />

Standing by the Lake of the Falls that day, I once again felt the<br />

power of the Bighorn backcountry. I now am more committed<br />

than ever to its protection – as a Canadian, as an Albertan and as<br />

one who loves to feel the tug of a healthy, native cutthroat trout<br />

on the end of my line.<br />

Katie is an ecologist and backcountry enthusiast living in Calgary.<br />

She is a board member of the soon to be Alberta BHA Chapter.<br />

<strong>SPRING</strong> 20<strong>17</strong> BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 5

TABLE OF CONTENTS<br />

Departments<br />

President’s Message 3<br />

In the Arena<br />

Your Backcountry 5<br />

Bighorn Wildland Provincial Park, Alberta<br />

BHA Headquarters News 8<br />

New Staff and Board Members, Membership Quadruples<br />

Backcountry Bounty 9<br />

Members Making Meat from Idaho to Texas, Arizona to Alaska<br />

Policy 11<br />

H.R. 622: Another Kick at the Hornet’s Nest<br />

Public Land Owner 13<br />

Kingdom Heritage Lands, Vermont<br />

Faces of BHA 15<br />

Ashley Kurtenbach – Deadwood, South Dakota<br />

Opinion 16<br />

Mea Culpa<br />

Backcountry Bistro 19<br />

Leftover Salmon Burgers<br />

Instructional 20<br />

How to be a Social Media Advocate for Conservation<br />

Kids’ Corner 25<br />

Eagle Eye Ash<br />

Chapter News 26<br />

End of the Line 62<br />

A Monumental Success<br />

Features<br />

Low and Slow: An Early Spring Float for Steelhead (Illustration) 32<br />

By Edward Anderson<br />

Q&A With Shane Mahoney 34<br />

By Sam Lungren<br />

Floating Through History and Wilderness: Retracing the Trail of 36<br />

Lewis and Clark in the Missouri River Breaks<br />

By E. Donnall Thomas Jr.<br />

Our Heritage of Desert: Public Lands in American History 40<br />

By Louis S. Warren<br />

The Ditch: A Love for Pheasants 44<br />

By Jeff Mishler<br />

Hunter-Angler-Biologist 50<br />

By Jesse Alston<br />

Five Places to Die (Fiction) 52<br />

By Michael Lein<br />

Someday 57<br />

By T.J. Hauge<br />

Alec Underwood photo<br />

6 | BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL <strong>SPRING</strong> 20<strong>17</strong><br />

<strong>SPRING</strong> 20<strong>17</strong> BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 7

BHA HEADQUARTERS<br />

BACKCOUNTRY BOUNTY<br />

BHA MEMBERSHIP QUADRUPLES<br />

BACKCOUNTRY HUNTERS & ANGLERS STARTED AS A GROUP OF SEVEN PEOPLE AROUND A CAMPFIRE in Oregon in<br />

the spring of 2004. Today, the organization counts more than 11,000 members around the campfire. With the raging debate regarding<br />

public lands over the past year, we’ve seen our membership double, triple and recently quadruple. As the campfire circle grows, so grows<br />

the movement to keep public lands in public hands. Welcome, new members!<br />

FOUR NEW STAFFERS HIRED<br />

1<br />

AS BHA’S MEMBERSHIP GROWS, the staff follows suit. Four public lands sportsmen and women have joined the BHA team in<br />

in recent months and are already contributing across the country.<br />

JASON AMARO, Southwest Chapter Coordinator. Growing up on<br />

the Rio Grande, Jason has chased everything that could swim, flock or<br />

walk. With his deep knowledge of the Southwest, he’s committed to<br />

serving the needs of the landscape and the BHA community from the<br />

ground up. He lives in Silver City, New Mexico.<br />

4<br />

CAITLIN FRISBIE, Office Manager. An avid angler and native Montanan,<br />

Caitlin brings a plethora of expertise and organizational drive<br />

to keep our Missoula, Montana, headquarters running smoothly and<br />

efficiently.<br />

2<br />

MIKE MCCONNELL, Central Idaho Coordinator. Mike is a bornand-bred<br />

Idahoan. With his strong background in wildlife biology, guiding<br />

and consulting, Mike is serving Central Idaho on the ground to<br />

conserve public lands, waters and wildlife for future generations.<br />

NICOLE QUALTIERI, Social Media and Online Advocacy Coordinator.<br />

Nicole comes to BHA from the world of hunting media. Through<br />

nearly two years of volunteering for BHA, she’s witnessed BHA’s growth<br />

firsthand and is looking forward to telling the BHA story online.<br />

NEW FACES ON NATIONAL BOARD<br />

3<br />

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

Hunter: Omari Bunn, BHA Member Species: Mule deer<br />

State: Idaho Method: Rifle Distance from nearest road:<br />

Five miles Transportation: Foot<br />

Hunter: Kyle Rademacher, BHA Member<br />

Species: Whitetail Deer State: Texas Method: Rifle<br />

Distance from nearest road: One mile<br />

Transportation: Foot<br />

Hunter: Troy Givens, BHA Member<br />

Species: Coues Deer State: Arizona Method: Rifle<br />

Distance from nearest road: One mile<br />

Transportation: Foot<br />

Angler: Emily Rex, BHA Member Species: Westslope<br />

Cutthroat State: Montana Method: Tenkara Distance<br />

nearest road: Four miles Transportation: Foot<br />

Hunter: Ford Van Fossan, BHA Member Species:<br />

Mountain Goat State: Idaho Method: Rifle Distance<br />

from nearest road: Four miles Transportation: Foot<br />

Hunter: CarolAnn Herring, BHA Member<br />

Species: Mule deer State: Montana Method: Rifle<br />

Distance from nearest road: Two miles<br />

Transportation: Bicycle<br />

Hunter: George Naughton, BHA Member<br />

Species: Caribou State: Alaska Method: Rifle Distance<br />

from nearest road: Seven miles Transportation: Canoe<br />

BHA WELCOMES HEATHER KELLY AND J.R. YOUNG to the national<br />

board of directors. An Anchorage, Alaska, native and owner of<br />

Heather’s Choice Meals for Adventuring, Heather brings a vast array of<br />

4<br />

outdoors experience and business savvy to the board. J.R., of Los Gatos,<br />

California, is a lifelong hunter and angler and a longtime member<br />

of BHA, moving up through the ranks from member to chapter leader,<br />

5<br />

to a natural fit on our national board.<br />

A big BHA thank you goes to Ben Long and Sean Clarkson for their<br />

extensive service and the time spent on the national board. Ben was the<br />

6<br />

glue that held together BHA for many years, during times when the<br />

future of the organization was uncertain. Sean provided an anchor on<br />

the East Coast that allowed BHA to expand rapidly. Their contributions<br />

to this organization’s growth and success cannot be overstated.<br />

7<br />

6<br />

7<br />

Send submissions to sam@backcountryhunters.org<br />

8 | BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL <strong>SPRING</strong> 20<strong>17</strong> <strong>SPRING</strong> 20<strong>17</strong> BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 9<br />

5

1<br />

2<br />

3<br />

PROTECT THE BACKCOUNTRY FOR LIFE<br />

BHA IS EXCITED TO ANNOUNCE A NEW PARTNERSHIP<br />

WITH ORVIS! BECOME A LIFE MEMBER TODAY AND<br />

RECEIVE A HELIOS II FLY ROD AND REEL COMBO.<br />

Backcountry Hunters & Anglers is proud to offer an extraordinary opportunity. Receive a FREE Orvis fly rod<br />

and reel package, Jackson kayak, Seek Outside bundle or Kimber firearm with your BHA Life Membership<br />

commitment. Become a leading contributor to a community of like-minded sportsmen and women who value<br />

the solitude, challenge and freedom of the backcountry experience. Help us protect and promote our legacy.<br />

Join for $2,500 and get a Jackson Kilroy LT Kayak (MSRP $1,899) or Coosa HD Kayak (MSRP $1,799)<br />

Or a Seek Outside 12-man Tipi Tent with liner and XXL stove (MSRP $2,135)<br />

Or a Kimber Mountain Ascent Rifle in the caliber of your choice (MSRP $2,040)<br />

Join for $1,500 and receive a Seek Outside Cimarron Shelter, stove jack, carbon pole, medium wood stove<br />

and a Unaweep Fortress 4800 Backpack with base talon (MSRP $1,250)<br />

Or a Kimber Stainless II .45 ACP pistol (MSRP $998)<br />

Or an Orvis Helios II Rod and Hydros Reel with line in 4, 5 or 6-weight in mid- or tip-flex (MSRP $1,349)<br />

Join for $1,000 and receive a Seek Outside Silvertip Shelter with guyline extension kit and Divide 4500<br />

Backpack (MSRP $640)<br />

Or a Kimber Micro Carry .380 pistol (MSRP $651)<br />

IN ADDITION YOU WILL RECEIVE:<br />

• Subscription to quarterly Backcountry Journal<br />

• Recognition in Backcountry Journal<br />

• Assurance that your dollars are helping conserve<br />

valued backcountry hunting and fishing traditions<br />

WELCOME, NEW LIFE MEMBERS!<br />

Charles Arbuckle<br />

Jeff Armantrout<br />

Michelle Bailey<br />

Mark W. Banks<br />

James Beabout<br />

Randall Beasley<br />

Nick Bissett<br />

Rick Blake<br />

Terrell Blanchard<br />

Bill Brass<br />

Ryan Brenteson<br />

Brian Bullock<br />

Damon Bungard<br />

Jason Burgess<br />

Julio Cabrera<br />

Daniel Callahan<br />

Sean Callahan<br />

Kendall Card<br />

Chris Cholette<br />

Scott Cripe<br />

Dan Crockett<br />

William Cullins<br />

Daniel Dale<br />

Pete Dial<br />

Jacob Dima<br />

Paul Dinkins<br />

Mitchel Doolin<br />

David Draper<br />

Dan Duncan<br />

Brandon Ellsworth<br />

Thomas Filgo<br />

Wesley Ford<br />

M.T. Gallagher<br />

John Garofalo<br />

John Gibson<br />

Steve Gili<br />

Alan Guile<br />

Taylor Hansen<br />

Jason Haskell<br />

Sean Hatch<br />

Mikkel Haugen<br />

Howard Holmes<br />

Brooks Horan<br />

Tyler Houston<br />

Tom Hull<br />

Michael Iten<br />

James Johnson<br />

Jason Kremer<br />

Jesse Kurtenbach<br />

Matthew Lee<br />

William Logiodice<br />

Braun Lowry<br />

Matt Maples<br />

Chris Maples<br />

John Marian<br />

Anthony Mastromarino<br />

Scott Mayer<br />

Mike Mihlfried<br />

Kyle Miller<br />

Robert Miller<br />

Mike Mongelli<br />

Kurt Mueller<br />

T.J. Nevin<br />

Ross Niebur<br />

Michael Panasci<br />

Kevin Parrott<br />

Anthony Perlinski<br />

Michael Peterson<br />

Shane Pinzka<br />

Tom Plaugher<br />

Sean Powell<br />

John Rasmussen<br />

John Redpath<br />

Brian Riopelle<br />

Shannon Scott<br />

Mark Seacat<br />

Terry Sloan<br />

Brian Solan<br />

James Stevens<br />

Hunter Stier<br />

Trevon Stoltzfus<br />

Patrick Stump<br />

Jack Tawney<br />

Michael Tollefsrud<br />

Lyle Vinson<br />

Camron Vollbrecht<br />

Todd Waldron<br />

Oliver White<br />

Luke Wiedel<br />

Matthew Wilcox<br />

Matt Williams<br />

Randall Williams<br />

Thomas Wilshusen<br />

James Zeck<br />

Abdul Zubaid<br />

INTERESTED? CALL OR EMAIL RYAN SILCOX:<br />

admin@backcountryhunters.org (406) 926-1908<br />

Photo courtesy of The Federal Law Enforcement Officers Association<br />

POLICY<br />

H.R. 622: ANOTHER KICK AT THE HORNET’S NEST<br />

BY ERIC NUSE<br />

ON JANUARY 24, REP. JASON CHAFFETZ introduced H.R.<br />

622, the so-called “Local Enforcement for Local Lands Act,”<br />

which would terminate the law enforcement functions of the<br />

U.S. Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management. In their<br />

place, this legislation would provide block grants to states for the<br />

enforcement of federal law on federal land.<br />

If you support small government and lower taxes, this might<br />

appear to be a good thing. According to Lanny Wagner, retired<br />

state chief law enforcement ranger with the BLM, thousands of<br />

federal law enforcement officers from the BLM and USFS would<br />

have their jobs eliminated. This would ostensibly save lots of<br />

money in salaries and benefits. Or would it? I suspect the under-staffed<br />

Border Patrol would scoop up these officers, resulting<br />

in a cost shift but no savings to taxpayers.<br />

So who fills in for these USFS and BLM officers? H.R. 622 proposes<br />

block grants to local and state law enforcement. As a former<br />

state game warden, I know these agencies could use more money.<br />

I also know that most don’t have the capacity to take on more<br />

work, especially outside their areas of expertise. Big money is pretty<br />

tempting bait, particularly for politicians who are only looking<br />

as far as the next election. Block grants are also notoriously easy<br />

to underfund or cut altogether. I doubt most agencies would be<br />

willing to invest in the training costs to take on new officers or<br />

retrain veteran officers based on shaky year-to-year block grants.<br />

This looks a lot like a bait-and-switch scheme to me.<br />

But even assuming the best – that funding is sufficient and the<br />

powers that be in Washington do continue the funding, what<br />

would be lost? According to Jay Webster, a retired patrol captain<br />

with USFS Law Enforcement and Investigations, “Local law enforcement<br />

is not going to be able to deal with specific issues like<br />

tribal rights, timber, fire and special uses.”<br />

Sen. Martin Heinrich described the proposed bill in a Huffington<br />

Post article as “a gift to poachers and drug runners.”<br />

Wagner added, “The potential loss of both natural and cultural<br />

resources due to the inability of the crimes to be investigated<br />

properly – or at all – would be devastating to current and future<br />

generations.”<br />

Federal Law Enforcement Officers Association (FLEOA) Executive<br />

Director Pat O’Carroll said, “Forest Service and Bureau of<br />

Land Management officers and agents conduct complex investigations<br />

crossing county, state and international borders. They are<br />

highly trained and routinely investigate the destruction of archaeological<br />

sites, timber theft, drug trafficking, illegal immigration,<br />

wildlife poaching and catastrophic wildfires.”<br />

In a letter to Rep. Chaffetz, FLEOA President Nathan Catura<br />

said the bill “will embolden those who view federal public lands as<br />

an intrusion on their constitutional rights. It will lead to further<br />

hostilities and encounters such as those recently played out on the<br />

Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon.”<br />

Beyond the diminished law enforcement function is the less<br />

obvious but very important function of officers being the on-theground<br />

representatives of their agencies. Most visitors to national<br />

forests or BLM lands will never see managers, who spend most of<br />

their time behind desks. But visitors will see officers who can answer<br />

their questions, pass along feedback to the resource managers<br />

and provide emergency assistance. Local law enforcement is great<br />

at what they do, but there is no way they can replace the agency<br />

knowledge and dedication of the USFS and BLM officers.<br />

Randy Newberg, host of the TV show Fresh Tracks and a passionate<br />

public lands user, summed up the threat to sportsmen as<br />

well as to the public at large: “What we see in H.R. 622 is surely<br />

an attack on the integrity of our public lands. This bill represents<br />

just one of many efforts by fringe elements seeking to impose<br />

their radical ideology on Americans, millions of Americans, who<br />

treasure these public lands. Public lands are one of America’s<br />

greatest treasures. Attacks on these lands and all they represent to<br />

American public land users are anti-hunting, anti-fishing and, at<br />

their core, anti-American.”<br />

Rep. Chaffetz quickly withdrew another bill introduced in conjunction<br />

with H.R. 622, the “Disposal of Excess Federal Lands<br />

Act,” H.R. 621. That bill would have mandated the sale of 3.3<br />

million acres of public lands. His decision to abandon the bill<br />

followed strong, outspoken and unrelenting criticism from BHA<br />

and other groups.<br />

We need to show lawmakers that messing with our public lands<br />

and the folks who manage and protect them is, as BHA President<br />

and CEO Land Tawney said, “Like kicking a hornet’s nest.” Most<br />

folks only kick once, but some are slow learners.<br />

Eric is a retired Vermont game warden and board member of the<br />

New England BHA Chapter.<br />

<strong>SPRING</strong> 20<strong>17</strong> BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 11

Michael Furtman photo<br />

PUBLIC LAND OWNER<br />

KINGDOM HERITAGE LANDS, VERMONT<br />

BY MATT BRETON<br />

I CUT THE BUCK’S TRACK BEFORE DAYLIGHT where he<br />

crossed the road off the snow-covered mountains to the west. It<br />

was the second to last day of the Vermont muzzleloader deer season,<br />

and the sand was rapidly sliding out of my hourglass. Following<br />

his track at sunup, I worked on sorting out his nighttime<br />

wanderings through private timberland, trying to stay warm on a<br />

cold December morning.<br />

The Kingdom Heritage Lands, tucked away in the northeast<br />

corner of Vermont, are a patchwork of private and government<br />

properties open to public hunting. Public access to these acres is<br />

protected through the collaboration of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife<br />

Service, the State of Vermont as well as nonprofit and private<br />

interests that demonstrate the value of conservation partnerships.<br />

The habitat is an extensive area of northern lowland forest and<br />

wetlands, ringed by hills and mountains of moderate elevation,<br />

drained by numerous streams flowing into the Connecticut River.<br />

Primarily boreal forest intermixed with hardwood, these lands<br />

support activities ranging from recreation-based tourism to wood<br />

harvest and maple sugaring. This forest region provides important<br />

habitat for numerous animal species on the edge of their ranges<br />

such as moose and spruce grouse. For New England sportsmen,<br />

the ability to hunt and fish timber company land borders on sacred.<br />

With 70 million people within a day’s drive, the existence<br />

of areas like this is uniquely important in satisfying the need to<br />

venture into remote stretches of wild country to track a whitetail<br />

buck or to land a brook trout that never before has risen to a<br />

fisherman’s fly.<br />

With the rut behind him, this buck was focused on recovering.<br />

His antlers left an impression in the snow on an old stump<br />

where he’d fed on mushrooms. Inadvertently I jumped him out<br />

of his morning bed, and the chase was on. The bucks of these<br />

big woods are wanderers by nature and typically cover miles of<br />

territory to feed, breed and finally head to their wintering areas.<br />

I followed him across several ridges heading steadily back uphill,<br />

noting where he stopped to check the wind. As the time and miles<br />

passed, I wondered if I’d get a chance to put my tag in his ear.<br />

In 1997, timber company Champion International decided to<br />

sell 132,000 acres in northeastern Vermont. This land had been<br />

managed for decades to produce an array of forest products with<br />

an emphasis on spruce-fir pulp wood for paper. The Conservation<br />

Fund of Arlington, Virginia purchased the ground in 1998 and<br />

a number of interested parties came together to protect and preserve<br />

this rich, multi-use area. TCF worked in partnership with<br />

the Vermont Land Trust, Vermont Agency of Natural Resources,<br />

Vermont Housing and Conservation Board, Vermont Chapter of<br />

The Nature Conservancy and USFWS to create a new model for<br />

the protection and management of large acreages in the northeast.<br />

This partnership is particularly special because of the focus<br />

on complementary management across the ownerships to achieve<br />

three equally important goals: working forests, ecological protection<br />

and public access.<br />

Doug Morin, a wildlife biologist/state land planner for the Vermont<br />

Department of Fish & Wildlife, called this arrangement<br />

“unique for Vermont and rare for New England.” He also said,<br />

“It might be a model for future public-private partnerships for<br />

industrial timberland.”<br />

The region’s people had a voice in shaping the direction of the<br />

Kingdom Heritage Lands with 35 public meetings, workshops<br />

and comment sessions – a level of input without precedent in Vermont.<br />

The management plan divided ecologically significant areas<br />

into federal land as part of the Silvio O. Conte National Wildlife<br />

Refuge and state land in the West Mountain Wildlife Management<br />

Area. The remaining acreage was purchased by Essex Timber<br />

Company, later sold to current owner Plum Creek Timber<br />

Company, for working forestry with easements protecting certain<br />

natural resources and guaranteeing perpetual public access.<br />

After several miles, the buck finally fed again and I knew he<br />

soon would lie down. Slowing my pace, I began to search the<br />

timber for his bedded form. I eased through one opening and<br />

then into another with slow, quiet steps. Then I spotted him only<br />

40 yards away. He slowly turned his head, revealing his antlers<br />

and confirming what his tracks had told me several hours earlier.<br />

The hanging black powder smoke slowly cleared. With the<br />

tracking job now complete, I set myself to the reverent tasks of<br />

dragging the deer out and getting him into my freezer.<br />

The Northeast is not known for its public hunting opportunities.<br />

As the timber industry changes, this unique collaboration<br />

of public, private and nonprofit partners has been a successful<br />

means to preserve and protect our wild places and traditions. I’ve<br />

hunted the Rocky Mountain West and I am thankful for the vast<br />

expanses available there, but being able to track a buck in classic<br />

New England fashion leaves me with a sense of accomplishment<br />

rooted in tradition. I am lucky to have a home landscape as rich<br />

and accessible as our Kingdom Heritage Lands.<br />

Matt is a native Vermonter who joined BHA after it dawned on<br />

him just how important public lands are, following a trip to Colorado<br />

to hunt elk. He helps produce the New England chapter e-newsletter.<br />

12 | BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL FALL 2016<br />

<strong>SPRING</strong> 20<strong>17</strong> BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 13

FACES OF BHA<br />

WAYS TO GIVE:<br />

BECOME A LEGACY PARTNER<br />

PLANNED GIVING<br />

BEQUESTS<br />

COMBINED FEDERAL CAMPAIGN<br />

WORKPLACE MATCH<br />

CHARITABLE ANNUITIES<br />

IRA ROLLOVER<br />

GO TO BACKCOUNTRYHUNTERS.ORG OR CALL GRANT ALBAN AT 406-926-1908 TODAY!<br />

ASHLEY KURTENBACH: Deadwood, South Dakota<br />

Fitness Competitor and Coach, Corporate Recruiter<br />

HOW DID YOU GET<br />

INTO HUNTING AND<br />

FISHING?<br />

I was born and raised in<br />

Iowa. My dad is a huge pheasant<br />

hunter and an avid deer<br />

hunter. I was around it but<br />

didn’t really do it. I didn’t have<br />

the equipment or the money.<br />

I’d ask my dad to come and<br />

he’d say, “Is this a joke? Because<br />

I’m not going to go out<br />

and buy stuff for you if you’re<br />

not 100 percent serious.”<br />

I didn’t get into hunting<br />

until I met Jesse. When we<br />

started dating, he was into<br />

hunting. I’d always wanted<br />

to learn and he was willing to<br />

teach me. I got my first bow.<br />

He made me practice for two<br />

years before we even went<br />

turkey hunting. At that time<br />

we lived on the east side of<br />

South Dakota. There wasn’t a<br />

lot of public lands so we had<br />

fewer opportunities. When<br />

we moved to the Black Hills,<br />

I was able to step it up because<br />

there’s so much more<br />

public land. I could go out<br />

every weekend. The last three<br />

or four years we’ve been going<br />

nonstop, as much as we can. I<br />

love it.<br />

WHAT ATTRACTED<br />

YOU TO BHA?<br />

I heard of it through social<br />

media last year. Jesse had an<br />

antelope tag in Utah last fall,<br />

and he filled it within a few<br />

days. We decided to get me an<br />

over-the-counter archery elk<br />

tag because we had blocked<br />

out 11 days for the antelope<br />

hunt. We have some friends<br />

who are on the board in Utah,<br />

Jason and Kait West. They said<br />

we’d be perfect to start a BHA<br />

chapter in South Dakota. We<br />

were talking general public<br />

lands stuff while we were on<br />

our trip, and they were helping<br />

us with our elk hunt.<br />

We talked about how it<br />

would be nice for South Dakota<br />

to have a chapter because<br />

it is needed. We have the same<br />

issues that so many other<br />

states are fighting. So, I contacted<br />

the organization and<br />

got enough people around it.<br />

We are just starting out, telling<br />

people, “Hey, this is a great<br />

organization. It’s been around<br />

for a while, but we are just getting<br />

the ball rolling in South<br />

Dakota.”<br />

HOW DOES FITNESS<br />

FACTOR INTO YOUR<br />

HUNTING?<br />

I train every year, regardless<br />

of competitions, for hunting<br />

season. I like to keep up with<br />

the boys as much as possible.<br />

I like carrying my fair share.<br />

I pack out my own animals.<br />

I train like mad for about six<br />

months before hunting season.<br />

I do cardio to help my endurance<br />

in the mountains. Weight<br />

training helps me carry my fair<br />

share of a deer. When I shoot<br />

an antelope, I carry the whole<br />

thing out by myself. I feel like<br />

I can contribute and people aren’t<br />

taking care of me.<br />

I also hunt a lot on my own.<br />

That’s a big thing for me and<br />

other women. If I go out and<br />

harvest something, I don’t need<br />

to call anyone because I know<br />

what to do. That’s rewarding<br />

to me. Especially when I am<br />

in a backcountry camp with a<br />

bunch of men and they’re like,<br />

“Holy crap, you can keep up<br />

with us.” That’s a compliment<br />

to me because that’s what I<br />

train for. It’s nice to be respected<br />

on that level, especially in<br />

a sport where men dominate.<br />

WHAT IS THE BIGGEST<br />

THREAT TO HUNTING<br />

AND FISHING?<br />

It’s a dying activity anymore.<br />

This is why I love BHA.<br />

It draws attention to future<br />

generations. If we lose public<br />

lands now, it won’t be here.<br />

Future generations won’t even<br />

get the option. I don’t have<br />

kids, but I’m super passionate<br />

about passing down the love of<br />

the outdoors.<br />

I see a lot of women getting<br />

involved. With more women<br />

hunting and fishing, hopefully<br />

there will be more kids. We<br />

also live in a world where kids<br />

are in a lot of extracurricular<br />

activities. Unfortunately, fewer<br />

people are taking the time<br />

to bring kids into the outdoors.<br />

If we lose public lands<br />

we will lose hunting even faster<br />

because there will be even<br />

fewer opportunities.<br />

<strong>SPRING</strong> 20<strong>17</strong> BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 15

OPINION<br />

MEA CULPA<br />

BY BENDRIX BAILEY<br />

I AM A POSTER BOY FOR BACKCOUNTRY PUBLIC LANDS<br />

conservation, literally (see Backcountry Journal Fall 2016, page<br />

18). The Nature Conservancy received my first ever donation to a<br />

charity when I was 28. I’ve lost track of all the conservation donations<br />

since then, other than my recent enlistments as a Backcountry<br />

Hunters & Anglers Life Member and Legacy Partner. Every<br />

day of the 33 years since that first donation I have advocated for,<br />

donated to and voted in favor of preserving wild places for all of<br />

us to enjoy. Yet, when I look in the mirror, I see the enemy.<br />

Success in business provided me with the means to purchase<br />

raw land, both near my home in Rochester, Massachusetts, and<br />

farther north in the unorganized township of T2R12, Maine. It<br />

is an accumulation of over 2,600 acres that will remain, as long as<br />

I live, wild and undeveloped. It is also posted against entry and I<br />

have no intention of opening it to the public.<br />

“What a hypocrite,” you might say. Here is a fellow who advocates<br />

for public wilderness but bars the public from land he owns.<br />

In 1998 I purchased my first parcel of wild land, a run-down<br />

cranberry bog with some upland and swamp totaling 50 acres. It<br />

is bordered by a road, a lake, a farm and, to the rear, over 2,000<br />

acres of largely untrammeled Swamp-Yankee wetland of brown<br />

brush, cedar, maple, white oak and tupelo. It is a whitetail haven<br />

in the midst of an ever crowding southeastern Massachusetts.<br />

Thanks to the gracious permission of the prior owner, I had<br />

been hunting the land for several years before I purchased it.<br />

There were others hunting the property, some with permission<br />

and some without. I purchased the land for bowhunting whitetail<br />

deer in the fall and the enjoyment of nature in the months<br />

between hunting seasons. I kept the land open, granted access to<br />

those who had it prior and asked those who did not to leave. Because<br />

I hunt exclusively with a longbow and because bowhunting<br />

is allowed during our shotgun and primitive arms season, I asked<br />

the other hunters to limit themselves to archery on that property.<br />

I’m just not comfortable up a tree in camo where guns are in use.<br />

Then one day while in my treestand I was rocked by the blast<br />

of a nearby 12 gauge. After helping the hunter drag his deer out,<br />

I revoked his permission to hunt on my property. Later that same<br />

year I caught another hunter and his pal removing my treestand.<br />

I won’t waste your time with the excuses each offered for violating<br />

the trust, but over time, I tired of dealing with other hunters and<br />

the frustration of having hunts disrupted, so I put up a fence and<br />

locked it. You can’t imagine how pleasurable it is for me to sit in<br />

the midst of all that wildness, undisturbed.<br />

A few years later I purchased some undevelopable swampland<br />

one town over. It is bordered by a highway, an industrial park and<br />

a neighborhood. I posted the land but provided contact information<br />

on the signs with an invitation to call for permission. Again<br />

I was startled out of my tree by an unpermitted shotgunner, was<br />

threatened by another who, as an ex-cop, promised I’d be persecuted<br />

by his fellow officers, and had treestands stolen.<br />

In 2011 I purchased 2,500 acres of timberland in Maine. It has<br />

eight and one half miles of logging roads with a single entrance<br />

and is backed by many square miles of conservation land. Hewing<br />

to Maine tradition, I left the land open to other hunters and<br />

nature lovers. Well, I did for a while. Over the course of the first<br />

year I was threatened by a drunk whom I asked to clean up the<br />

beer bottles he had strewn about and had my truck vandalized<br />

by a crew of bird hunters who objected to my blocking one of<br />

the roads while bowhunting at the end of it. You guessed it. A<br />

gate went up at that single entrance. My phone number is welded<br />

into that gate, and I still allow those who ask first to access the<br />

property, but like more and more land in Maine and elsewhere,<br />

there is that gate. That gate means you can’t enjoy those woods<br />

on a whim. You can’t meander up into those four square miles,<br />

fish the two ponds and the brooks that flow from them, and you<br />

can’t camp at the old campsite out back while exploring Maine’s<br />

forests. You have to plan ahead and get permission. Mostly, you<br />

just slow down then drive by. You might be one of the good guys,<br />

but sadly, there are enough bad guys out there to ruin it for all.<br />

I could explain how hard I worked to afford those properties.<br />

I could describe how much the hunting, the solitude and the nature<br />

mean to me, and how stressful interactions with unpleasant<br />

people can ruin it. I could explain, but when I was done, you’d<br />

probably just say something like Don Thomas said when he characterized<br />

one Montana landowner as a man who, “would be of<br />

little consequence except for the staggering number of zeros on<br />

the numbers at the end of his bank account.” While mine will<br />

stagger no one, the point is made. A man who can afford to purchase<br />

land and lock it up deserves the worst sort of vilification<br />

from those who cannot.<br />

Or does he? And be patient for just a moment more. I’m getting to<br />

the point.<br />

I hunt public lands also. I love public lands. It was all I had for<br />

years. I hang with other public lands hunters and I’ve heard the stories<br />

of hunts busted by inconsiderate hunters who blow in, knowingly or<br />

otherwise, and spoil a perfect setup. It only happens so many times before<br />

you start wishing you could have this little corner all to yourself,<br />

for just a day or two.<br />

Closer to home, I don’t open my door to random strangers, and<br />

most likely, neither do you. There is a thing about ownership that<br />

makes us feel we have a right to control what we own. It is in our nature,<br />

and it is in our laws. And that is why when I look in the mirror I<br />

see the enemy. And why, when you look in the mirror, you should see<br />

the enemy. We all become the enemy of general public access as soon<br />

as we own the land. Given the means to own it, someone, someday<br />

will motivate you to restrict or perhaps close it.<br />

And that’s my point, and that’s why I’m a Life Member and Legacy<br />

Partner of BHA. Without public lands our hunting heritage will devolve<br />

into a feudal system of owned wildlife that only the privileged<br />

may pursue. The North American Model is unique, and it relies on<br />

public lands. Public lands are our only protection against our own<br />

nature. For that reason, the fight to preserve the public lands heritage<br />

is one we must not lose.<br />

Bendrix hunts with a longbow, canoes and camps with his family and<br />

is a registered Maine guide. Founder of Measurement Computing, he has<br />

participated in three technology startups since graduating from Babson<br />

College in 1979.<br />

16 | BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL <strong>SPRING</strong> 20<strong>17</strong> WINTER 2016 BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | <strong>17</strong>

BACKCOUNTRY BISTRO<br />

LEFTOVER SALMON BURGERS<br />

BY J.R. YOUNG<br />

WHEN I STARTED FISHING REGULARLY with a local charter<br />

for salmon out of Emeryville, California, I noticed the sea lions<br />

awaiting the fleet’s return to the harbor. Once back at the docks,<br />

the deckhands would feverishly work to finish fileting out everyone’s<br />

fish. They often tossed the carcasses into the water for an<br />

easy meal for the sea lions lurking close by. Solid eats for them,<br />

but I’d always opt to take my fish home whole and process them<br />

myself, much to the lions’ disappointment. After cutting up my<br />

fish, I save the heads to bury deep beneath the tomato plants in<br />

my garden (based on the recommendations of a world-renowned<br />

tomato specialist; but really, this is a whole other story). I boil the<br />

carcasses for fish stock, but I quickly noticed just how much meat<br />

still remained from fileting. I figured it could be put to better use.<br />

Looking at a salmon carcass that has been fileted, you’ll notice<br />

there’s quite of bit of meat hanging between the bones around the<br />

spine. This is true for most fish over two or three pounds, and I<br />

would recomend this recipe for pike, bass, trout and pretty much<br />

any fish large enough. Now I can’t remember if it was a technique<br />

I saw in a recipe or if, one day, I just decided to pick up a spoon<br />

and try and get all the additional meat. Running the spoon down<br />

the spine initially and then parallel with the rib bones I was able<br />

to clear most of the flesh. I was amazed at just how much was<br />

there. Four Chinook at roughly 10 to 12 pounds each (whole)<br />

yielded a couple pounds of meat.<br />

With a bowl full of bonus raw salmon, the possibilities are endless.<br />

Fresh king salmon loves a grill, so burgers, in my opinion, are<br />

a fantastic option. Some might call it a cake, for the similarity to<br />

crab cakes. You can really go any way you want with seasoning,<br />

but I like to keep it simple. The trick is to make sure any larger<br />

bits of meat are finely chopped, and that there is something to<br />

bind the meat together.<br />

INGREDIENTS:<br />

1½-2 lbs of finely chopped salmon meat<br />

1 egg<br />

¼ cup breadcrumbs<br />

1 tsp fresh ground pepper<br />

1 tsp sea salt<br />

1 tbs lemon juice<br />

1 clove garlic, pressed<br />

1 tsp dried thyme<br />

First, scrape your salmon carcasses of all residual meat. In a<br />

bowl, mix the salmon, egg, breadcrumbs, pepper, lemon juice,<br />

pressed garlic and thyme (hold the salt for now). Once all is incorporated,<br />

let it rest for 10 minutes to help binding. Next form the<br />

burger patties. Work as gently as possible, but get the job done. If<br />

they aren’t binding, try adding a little more egg or breadcrumbs.<br />

Once the patties are formed, sprinkle salt on top and start grilling<br />

over your favorite form of fire. I like to grill mine medium,<br />

but there’s nothing wrong with cooking a little more. Well done it<br />

will get dense and chewy, however.<br />

Once the burgers are done, dress them up with an aioli or tartar<br />

sauce. Toss on a tomato, grilled onions and/or some lettuce. It’s a<br />

burger; make it your way. Once you get the basics, tweak the spices,<br />

add a dash of soy sauce or toasted sesame oil. Add some ginger<br />

for an Asian flair, chipotle and cumin for Mexican or Herbes de<br />

Provence for French. Have fun and get more from your fish!<br />

J.R. was born and raised in Washington where salmon was a staple<br />

of his diet. He currently lives in the Bay Area of California with his<br />

wife, son, dog and chickens. He recently joined BHA’s national board<br />

and will be cooking at the Field to Table Dinner at the 20<strong>17</strong> BHA<br />

North American Rendezvous.<br />

<strong>SPRING</strong> 20<strong>17</strong> BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 19

INSTRUCTIONAL<br />

2<br />

SHOW OFF WHAT MOTHER NATURE GAVE YA<br />

Your coworkers might not understand why wild<br />

places are important to you, but with the help of<br />

social media it’s easy to shine a light on what makes<br />

these lands great. Showcase stunning landscapes,<br />

demonstrate your knowledge of and reverence for the<br />

animals or fish you’re chasing, and share the reasons<br />

why public lands are meaningful to you.<br />

FOLLOW POLICYMAKERS<br />

3<br />

These days, social media can have<br />

a major impact on legislation. Think<br />

about it: These platforms give us the<br />

means to react instantly to proposed<br />

bills and voice our support or opposition<br />

directly to the source, our elected<br />

officials. We witnessed the impact social<br />

media can have on legislation firsthand back in February when<br />

Rep. Jason Chaffetz announced on Instagram that he was withdrawing<br />

H.R. 621, which called for the sale of 3.3 million acres<br />

of public lands, within days of its introduction. He backpedaled<br />

after a tidal wave of opposition crashed over his social media accounts.<br />

Collectively, thousands of public land enthusiasts made a<br />

difference by using hashtags such as #keepitpublic and explaining<br />

why any sale of our public lands is a bad thing.<br />

When you decide to comment on elected officials’ social media<br />

pages, be sure to compose your thoughts in a respectful and positive<br />

manner. Cursing, threatening and trolling are unnecessary<br />

and can perpetuate misleading stereotypes surrounding the hunting<br />

and angling community.<br />

How to be a Social Media Advocate<br />

for Conservation and Public Lands<br />

BY ALLIE D’ANDREA<br />

#KEEPITPUBLIC<br />

SOCIAL MEDIA IS NO LONGER JUST FOR CREEPING on<br />

your ex or showing off the buck you killed last fall. Several of<br />

the popular platforms like Facebook, Instagram and Twitter have<br />

morphed into forums of public opinion, virtual soapboxes for the<br />

presentation and debate of ideas. These are places to raise awareness<br />

for issues near and dear to our hearts, start conversations and<br />

show the world who we are as conservation-minded sportsmen<br />

and women.<br />

You don’t need to be the world’s next selfie-studded Instagram<br />

star to be an effective advocate for conservation. In fact, your page<br />

does not even need to be public! There’s a pretty good chance<br />

that some of your friends and family are not up to speed on current<br />

policy and legislation regarding wildlife, public lands transfers<br />

and natural resources. Every person you enlighten is another<br />

potential vote on our behalf. Here are a few tips for how you<br />

can join the fight to protect our sporting heritage through your<br />

smartphone or computer.<br />

Allie is the digital marketing manager at First Lite and shares her<br />

adventures through social media under the handle Outdoors Allie.<br />

She is a lover of all things outdoors and uses her platform to highlight<br />

the importance of conservation and the vitality of our public lands.<br />

4<br />

SHARE CONSERVATION EVENTS<br />

Going to your local BHA chapter’s<br />

pint night? Volunteering on a habitat<br />

restoration project? Headed to Missoula<br />

for the North American Rendezvous<br />

this spring? Post about it! Sharing events<br />

KEEP IT CLASSY<br />

5<br />

No one wants to see that weird photo<br />

of your brother biting the head off<br />

a trout; you can save it for blackmail<br />

at Thanksgiving. Hunters, anglers and<br />

outdoor enthusiasts alike have a responsibility<br />

to show respect for America’s<br />

public lands, including the critters that<br />

live there. Blood is unavoidable when killing an animal, but try to<br />

keep it to a minimum in posts online. The uninitiated are often<br />

on social media helps spread the word. The more folks who know<br />

about and attend these gatherings, the better. Never been to a<br />

BHA event? Give it a go. You can expect good beer, good people<br />

and great conversation. Make sure to take pictures while you’re<br />

there and show how much fun you had!<br />

more sensitive to gore. Keep that trout wet, tuck that lolling elk<br />

tongue and lay out your ducks in a way that displays their beauty<br />

rather than a pile of wet feathers.<br />

We’ve entered an age where social media can mold public opinion,<br />

change policy, even affect elections. It’s up to us as sportsmen<br />

and women to take advantage of that capacity and advocate for<br />

the things that matter to us: clean water, intact ecosystems, sporting<br />

traditions and keeping public lands in public hands.<br />

1<br />

PRESS #<br />

Hashtags have the power to unite our voices as<br />

public land owners and increase engagement among<br />

new folks looking to join our ranks. Don’t know<br />

what hashtag to use? Check the bio of BHA’s Instagram<br />

for the latest: #KeepItPublic, #PublicLand-<br />

Owner, #StreamAccessNow.<br />

For those of you with private pages, your photos<br />

will not pop up in the hashtag streams; however,<br />

that does not mean you should disregard this point.<br />

Hashtags in your post will be seen by your followers<br />

(including your nosey mom who likes every single<br />

one of your photos), which still helps raise awareness.<br />

Tim Romano photo<br />

20 | BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL <strong>SPRING</strong> 20<strong>17</strong>

22 | BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL FALL 2016<br />

<strong>SPRING</strong> 20<strong>17</strong> BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 23

KIDS’ CORNER<br />

EAGLE EYE ASH<br />

The View from a Young<br />

Birdwatcher’s Treehouse<br />

BY KRIS MILLGATE<br />

MY NAME IS ASHLEY AND I’M 12.<br />

I was born in Pennsylvania, but I live in Idaho.<br />

Our house is in the country and we have big trees.<br />

We’re building a tree cabin in one of the trees.<br />

There’s a spotting scope up there too.<br />

I use it to spy on a bald eagle nest about a mile away.<br />

I’ve fished a few times, but I’ve never caught anything.<br />

With birds, I always see something.<br />

Sometimes I see the mom, or dad, it’s hard to tell, sitting on top of the nest feeding the babies.<br />

To pass food, the mom puts her legs on top of the nest and bends down to the baby’s head, just like a little kiss.<br />

Baby eagles have black heads, but adults have white heads.<br />

I was born blond, but now I’m brown so it’s probably something like that.<br />

A lot of other kids don’t know about eagles because they don’t go outside.<br />

They stay inside on their technology all day, but they should go out.<br />

If you see something on your phone, that’s not like seeing something for real. On Instagram, you can just scroll past something and<br />

like it. That’s not like actually being there. If you’re outside, you feel nature all around you instead of sitting on the couch.<br />

It’s better outside.<br />

Kris is an outdoor journalist based in Idaho Falls. See more of her work at www.tightlinemedia.com.<br />

24 | BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL FALL 2016 <strong>SPRING</strong> 20<strong>17</strong> BACKCOUNTRY JOURNAL | 25

CHAPTER NEWS<br />

BHA STATE CHAPTERS:<br />

Spreading the Word from State<br />

Capitals to Breweries and Instagram<br />

ARIZONA<br />

The main focus of the Arizona<br />

Chapter currently is our OHV signage<br />

project. The purpose of this project is to<br />

educate Arizona OHV users on the impact<br />

that improper use has on habitat and wildlife.<br />

With the help of the Arizona Game &<br />

Fish Department and Arizona State Parks,<br />

we are working with the appropriate land<br />

agencies to nail down the final locations<br />

where the signs will be installed. Once this<br />

is complete we will reach out to local volunteers<br />

to install signs across the state that<br />

stress the importance of riding legally.<br />

Our membership is growing due in<br />

large part to the hard work of all of our<br />

chapter leaders and members who help<br />

spread awareness for BHA’s mission. This<br />

will lead to more events and activities that<br />

the whole family can enjoy. We have also<br />

created an AZ BHA Instagram account (@<br />

backcountryhuntersaz) in addition to our<br />

Facebook group to help spread the word<br />

about what we do. These are great ways to<br />

notify members and prospective members<br />

about upcoming events and issues. Give us<br />

a follow to find out when and where we<br />

hold events! -Justin Nelson<br />

BRITISH COLUMBIA<br />

British Columbia BHA has had<br />

an amazingly busy first three months of<br />

20<strong>17</strong>. We hosted our 3 rd annual Hunting<br />

Film Tour at the Key City Theatre in<br />

Cranbrook on February 25. The event<br />

continues to grow each year. We attracted<br />

over 300 local hunters to this year’s event.<br />

We signed up 14 new members and 11<br />

renewals that night as well. Thank you to<br />

Alan Duffy, the chair of the HFT committee,<br />

and his hard-working committee for<br />

another successful fundraiser to propagate<br />

our cause here in British Columbia.<br />

BCBHA also spearheaded a collaboration<br />

of diverse stakeholder groups, the<br />

Wildlife Management Roundtable, in<br />

Cranbrook on March 11. It was a collaboration<br />

of diverse stakeholder groups. Wildlife<br />

populations are on the decline across<br />

the province, and that urged BCBHA<br />

to organize and host this unprecedented<br />

event to make wildlife management a<br />

priority in British Columbia ahead of the<br />

provincial election in May. The groups invited<br />

to collaborate included the East Kootenay<br />

Wildlife Association, the Elk Valley<br />

Rod & Gun Clubs, Southern Guides &<br />

Outfitters, First Nations and Wildsight,<br />

the largest environmental organization<br />

in the Kootenays. We put our differences<br />

aside for the day and aligned our common<br />

interests in unity for wildlife and habitat.<br />

The format for the roundtable included a<br />

neutral moderator, a “state of the resource”<br />

slide presentation and an opportunity for<br />

a representative from each group to speak<br />

on the issues as they pertain to their membership/mandate.<br />

The meeting was an<br />

overwhelming success in the goals we set<br />

out to achieve. We packed the venue with<br />

a capacity crowd of over 350 people, and<br />

we had a clear message to government to<br />

make wildlife management a priority in<br />

BC. All candidates, six in total, running<br />

for the two MLA (Member of Legislative<br />

Assembly) seats in our region also had an<br />

opportunity to address the crowd on what<br />

they were going to do for wildlife if elected.<br />

There was overwhelming media attention<br />

from radio and newspaper, global TV and<br />

Shaw cable. Although BCBHA was the<br />

catalyst to get these groups together and<br />

for the common message, this event raised<br />

our profile in the province and boosted<br />

our credibility as a legitimate stakeholder<br />

in BC. Thank you to the hard-working<br />

committee who organized and succeeded<br />

in hosting one of the most important, if<br />

not the most important, wildlife meetings<br />

in the Kootenays in over 25 years. -Bill<br />

Hanlon<br />

CALIFORNIA<br />

Friday, Feb. <strong>17</strong> was the deadline<br />

to introduce legislation for the California<br />

State legislature. We are currently poring<br />

through the 2495 bills introduced this<br />

year. As we identify bills in the course doing<br />

this, we’ll compile that list and post it<br />

to chapter members. Many of these bills<br />

are considered spot bills and do not yet<br />

contain details necessary for a complete<br />

analysis. All of them need to be in print for<br />

30 days before they can be heard in committee.<br />

The first policy committee hearing<br />

is generally where bills take their first substantive<br />

amendments.<br />

In February we were in Sacramento at<br />

the Hunting Film Tour. The chapter raised<br />

almost $1,000 at the event, which, despite<br />

a lower than expected turnout, was a great<br />

success for us. Every person who walked in<br />

to the theater wanted to know about BHA<br />

and what we represent!<br />

Look for regional chapter events in the<br />

state this year. We’re currently working on<br />

a pint night event for both Northern and<br />

Southern California to kick things off and<br />

raise awareness. We’ll also be represented<br />

at the “1000 BC Shoot” at San Francisco<br />

Archers in August, where we hope to have<br />

a booth and support the event with some<br />

archers. Please plan on attending an event<br />

in your region, even if it means a long<br />

drive! -George McCloskey and J.R. Young<br />

COLORADO<br />

The Colorado Chapter welcomed<br />

Don Holmstrom to their leadership<br />

team as the habitat watch volunteer<br />

program coordinator. In addition, two<br />

new HWVs have joined the ranks: John<br />

Grosvenor is Colorado BHA’s first HWV<br />

for the Grand Mesa National Forest and<br />

Rob Mahaffey is the chapter’s first HWV<br />

for the Pawnee National Grasslands.<br />

Thanks guys!<br />

The chapter held public lands pint<br />

The British Columbia Chapter<br />

hosted a highly successful<br />

roundtable in March to<br />

discuss wildlife issues with all<br />

concerned user groups.<br />

nights in Gunnison, Paonia, Fort Collins,<br />

Grand Junction, Greenwood Village and<br />

Colorado Springs (with more to follow)!<br />

Thanks to Adam Gall, Tony Prendergast,<br />

Kevin Alexander, Sawyer Connelly, Rick<br />

Seymour, Jeff Finn and Tyrell Woodward<br />

for setting these up.<br />

Southwest Regional Director Dan Parkinson<br />

wrote an op-ed on the impacts of<br />

sheep grazing allotments on bighorn sheep<br />

in southwest Colorado’s San Juan Mountains.<br />

Central West Slope Regional Director<br />

Craig Grother submitted comments<br />

on motorized recreational trail grant applications,<br />

and the chapter submitted BLM<br />

Little Snake Field Office Travel Management<br />

Area 2 scoping comments. Join us<br />

for Colorado BHA’s 3rd Annual Wild<br />

Game Cook-Off at Grossen Bart Brewery<br />

in Longmont on May 5. Contact Geordie<br />

Robinson for additional information<br />

at geordie.robinson4@gmail.com. -David<br />

Lien<br />

IDAHO<br />

The Idaho Chapter’s annual board<br />

meeting was held in December<br />

along the banks of the Snake River. Cochair<br />

terms expired for Derrick Reeves<br />

and Ian Malepeai, who were replaced by<br />

Wildlife Management Roundtable<br />

March 11th, 1-3pm<br />

Heritage Inn- Cranbrook<br />

B.C<br />

Admission: Free and<br />

open to the General<br />

Public<br />

THIS UNPRECEDENTED EVENT is<br />

a collaboration of conservation<br />

groups aligning their common<br />

interests to make wildlife<br />

management a priority in British<br />

Columbia and improve wildlife<br />

populations in the Kootenays and<br />

the province.<br />

Invites have been extended to the<br />

political candidates for the upcoming<br />

provincial election in both the<br />

Kootenay East and Columbia ridings<br />

and all have indicated they will be in<br />

attendance.<br />

Everyone concerned with the state of our<br />

wildlife populations is urged to attend.<br />

Eric Crawford (Moscow) and Josh Kuntz<br />

(Boise), who now join Merritt Horsmon<br />

(Pocatello) as co-chairs. Sierra Robatchek<br />

became the University of Idaho BHA<br />

program coordinator. In an effort to have<br />