NovaTerra - Connected Cities

NovaTerra - Connected Cities

NovaTerra - Connected Cities

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

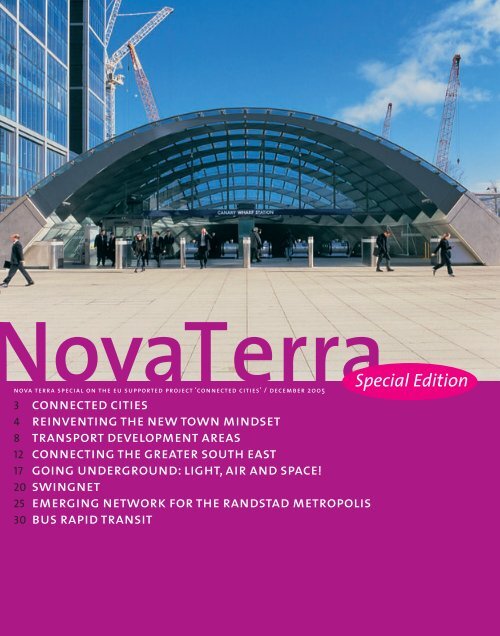

ovaTerra<br />

nova terra special on the eu supported project ‘connected cities’ / december 2005<br />

3 connected cities<br />

4 reinventing the new town mindset<br />

8 transport development areas<br />

12 connecting the greater south east<br />

17 going underground: light, air and space!<br />

20 swingnet<br />

25 emerging network for the randstad metropolis<br />

30 bus rapid transit<br />

Special Edition

Nova Terra Special on the EU<br />

supported project ‘<strong>Connected</strong><br />

<strong>Cities</strong>’, December 2005.<br />

http://connectedcities.net<br />

Publisher<br />

Nirov, The Hague, The<br />

Netherlands (www.nirov.nl)<br />

Editorial Board<br />

Jan Hein Boersma<br />

Evelien Brandes<br />

Yttje Feddes<br />

Huib Haccou<br />

Frank van der Hoeven (issue<br />

editor)<br />

Derek Middleton (English<br />

editing)<br />

Michiel Smit (editor in chief)<br />

Josja van der Veer<br />

Graphic design<br />

Studio Bau Winkel, Martijn<br />

van Overbruggen<br />

Print<br />

Grafisch Bedrijf Tuijtel,<br />

Hardinxveld-Giessendam<br />

Correspondence<br />

Nirov, Michiel Smit,<br />

Postbox 30833, 2500 GV<br />

The Hague, The Netherlands,<br />

smit@nirov.nl<br />

Office support:<br />

Helen Kokshoorn,<br />

kokshoorn@nirov.nl<br />

ISSN<br />

1570-0402<br />

Project part-financed<br />

by the European Union<br />

Content<br />

17<br />

Editorial<br />

3 connected cities<br />

Frank van der Hoeven<br />

4 reinventing the new<br />

town mindset<br />

Pascaline Gaborit<br />

8 transport development areas<br />

Peter Hine, Jeremy Edge, Kathy Gal and Michael Chambers<br />

Sustainable development and growing mobility in<br />

the South East of England<br />

12 connecting the greater<br />

south east<br />

Arno Schmickler<br />

Cover illustration: Netherlands Centre for the Underground Construction, Gouda<br />

4<br />

22<br />

8<br />

27<br />

17 going underground:<br />

light, air and space!<br />

Inge van Berkel<br />

22 swingnet<br />

Frank van der Hoeven<br />

27 emerging network for the<br />

randstad metropolis<br />

Daan Zandbelt<br />

40 bus rapid transit<br />

Stefan van der Spek and Jacques Splint<br />

12<br />

40

<strong>NovaTerra</strong> <strong>Connected</strong> <strong>Cities</strong> / december 2005 / 3<br />

<strong>Connected</strong> <strong>Cities</strong><br />

Frank van der Hoeven, Delft University of Technology, Lead Partner <strong>Connected</strong> <strong>Cities</strong><br />

Nova Terra is a not-for-profit magazine. It publishes<br />

mainly in Dutch and is distributed to two networks in the<br />

Netherlands: Habiforum and the Netherlands Institute<br />

for Housing and Planning (Nirov). Both work to raise and<br />

maintain the quality of spatial plans, urban design and<br />

development projects. This English language supplement<br />

to Nova Terra is dedicated to the activities of the<br />

<strong>Connected</strong> <strong>Cities</strong> project, an EU-sponsored Interreg IIIC<br />

network for sustainable mobility and spatial<br />

development, and dedicated to improving accessibility<br />

and quality of life in urban and rural areas.<br />

<strong>Connected</strong> <strong>Cities</strong> will ‘travel’ through Europe; every six<br />

months the focus and the location of activities will<br />

shift to another region. Starting off in the Belgium/<br />

Netherlands region, it will proceed to Bulgaria/Greece,<br />

Portugal/Spain and Italy/Greece, before concluding in<br />

the England/France region. The central issues during the<br />

first six months are changing urban relations, highquality<br />

public transport and Transport Development<br />

Areas. This supplement reflects that focus. New Towns,<br />

once a promising solution to deal with metropolitan<br />

growth in Europe, now seem to be struggling with the<br />

development of multi-centred urban areas. Originally<br />

built to serve a one-to-one relation with their mother<br />

city, the New Towns are being forced to reinvent their<br />

role, identity and transport provision.<br />

Fifty years have gone by since the first New Towns<br />

emerged. Metropolitan development in South East<br />

England is now guided by the Sustainable Communities<br />

programme, which revolves around four growth areas<br />

adjacent to London. It will be interesting to see during<br />

the course of <strong>Connected</strong> <strong>Cities</strong> how this new thinking<br />

engages older practices. Prominently located in the<br />

growth areas outlined by the Sustainable Communities<br />

programme are two New Towns: Basildon in the Thames<br />

Gateway and Milton Keynes in Milton Keynes-South<br />

Midlands. The idea of Transport Development Areas<br />

(TDAs) may play a key role in these new or reinvented<br />

ideas. TDAs are about concentrating urban growth in<br />

areas well-served by public transport, an approach that<br />

can readily be incorporated into the spatial or urban<br />

planning of many cities and regions in Europe. But it is<br />

the first time that such a practice has been explicitly<br />

labelled and presented as a coherent set of actions.<br />

This may help to focus attention on existing policies<br />

and plans that support the idea, as well as implant the<br />

concept where no such ‘tradition’ exists.<br />

The Dutch province of Zuid-Holland is struggling to<br />

become metropolitan and seems to be developing its<br />

own version of TDAs: Stedenbaan. This conversion of<br />

older transport systems into new ones goes hand in hand<br />

with a shift in spatial policies. But as the transit systems<br />

in Zuid-Holland goes through a period of rapid change,<br />

who is actually keeping an eye on the network as a<br />

whole? The fact that technical distinctions between light<br />

rail, metro, rapid transit, commuter train and regiotram<br />

have all but disappeared has not been reflected in<br />

practice. For underground construction it matters little<br />

what direction the development of such a network takes,<br />

and in dense urban areas it is clear that vast stretches<br />

will have be built underground. After decades of<br />

experience in the use of underground facilities, we have<br />

come to understand that underground facilities need<br />

different design and management strategies to deliver<br />

their full potential.<br />

With so much attention for rail-based transport one<br />

could easily overlook Bus Raid Transit. <strong>Cities</strong> that do not<br />

yet have a high-quality public transport system might<br />

want to look into the improved bus systems currently<br />

offer, which can meet high standards at a much lower<br />

price. The case of Phileas in Eindhoven shows that the<br />

planning of such a transport system can be integrated<br />

into the urban planning process. Which brings us back<br />

to the core of <strong>Connected</strong> <strong>Cities</strong> – the cutting edge of<br />

sustainable mobility and spatial planning.<br />

Z

<strong>NovaTerra</strong> <strong>Connected</strong> <strong>Cities</strong> / december 2005 / 4<br />

William Morris (1868)<br />

The idea of the New Town<br />

was based upon the Garden<br />

<strong>Cities</strong> concept by Ebenezer<br />

Howard in 1902.

<strong>NovaTerra</strong> <strong>Connected</strong> <strong>Cities</strong> / december 2005 / 5<br />

Reinventing<br />

the New Town mindset<br />

The New Towns were built in response to demographic growth, urban sprawl and uncontrolled<br />

metropolitan expansion. But they have only partly lived up to their promise and now experience<br />

similar problems to the suburbs: poor public transport, dependency on the private car and low<br />

urban densities. The New Town concept needs to be reinvented to promote sustainable transport<br />

and development.<br />

Pascaline Gaborit, The European New Towns Platform (ENTP), Brussels<br />

The idea of the New Town arose at the turn<br />

of the 20th century with the publication in<br />

1902 of Ebenezer Howard’s Garden <strong>Cities</strong><br />

of Tomorrow. After the Second World War,<br />

the UK Ministry of Town and Country<br />

Planning launched an extensive New Towns<br />

programme under the New Towns Act 1946.<br />

Since then 21 New Towns have been<br />

established in the UK and more than 40 in<br />

the whole of Europe. With hindsight, building<br />

New Towns from scratch cannot be considered<br />

a very environmentally friendly form of<br />

development. Although the New Towns did<br />

retain some green areas, they did not preserve<br />

the original landscape or its biodiversity.<br />

The New Towns were created alongside<br />

existing towns or around several villages.<br />

They attracted ‘neo-urban’ residents, who<br />

use different centres for shopping (malls<br />

or out-of-town centres), employment<br />

(‘technopoles’) and entertainment (cinemas,<br />

green parks, leisure centres and sports<br />

stadiums). These urban mutations are so<br />

deep and radical that they pervade all<br />

aspects of society, from mobility to the<br />

design of buildings. They affect lifestyles,<br />

families, consumers, employees and workers<br />

in the New Towns and in the periphery.<br />

For most New Towns the era of rapid growth<br />

is over and they now face similar problems:<br />

poor transport facilities apart from the links<br />

to the mother cities, poorly designed<br />

housing, simultaneous ageing of buildings,<br />

outdated infrastructure and a poor image.<br />

They generally lack a proper town centre,<br />

were built to low urban densities and have<br />

recently attracted low income households.<br />

The challenge facing New Towns face is to<br />

consolidate consolidating and restructure<br />

the urban fabric to accommodate changes<br />

in the population structure, household<br />

structure and lifestyles, and to redefine their<br />

sustainability objectives.<br />

household and demographic change<br />

In the New Towns, as in most European<br />

suburbs, housing was designed for nuclear<br />

families. As the quality of public transport<br />

serves was average at best, this group<br />

became largely dependent on the private<br />

car and this had a direct impact on family<br />

structures. Women were more or less<br />

prevented from taking paid employment and<br />

had to stay at home to care for their families.<br />

The New Towns generally did not provide<br />

leisure activities for children or kindergartens<br />

and crèches within walking distance, as in<br />

the old centres.<br />

The housing stock in the New Towns made<br />

a similar impact on public life. In Milton<br />

Keynes, for instance, ‘the single family<br />

housing was emphasised for nuclear<br />

families with two children, assuming a male<br />

breadwinner and a female homemaker.’ 1<br />

The problems of accessibility outlined above<br />

limit the opportunities open to women<br />

by reducing the possibility of combining<br />

domestic tasks with employment,<br />

disadvantaging women in the labour market.<br />

In the industrialised world this situation is<br />

now changing. Local authorities face two<br />

important demographic processes: the<br />

arrival of foreign migrants with large<br />

families and low incomes in need of decent<br />

housing, and the ageing of the population.<br />

In the Dutch New Town of Spijkenisse, for<br />

example, only ten per cent of the population<br />

Y

<strong>NovaTerra</strong> <strong>Connected</strong> <strong>Cities</strong> / december 2005 / 6<br />

The image and<br />

attractiveness<br />

of New Towns<br />

has declined<br />

The Dutch New Town of Spijkenisse, near Rotterdam. (photo: Mischa Keijser/ HH)<br />

was above 55 years old in 1983, but this will<br />

rise to twenty-five percent in 2009. 2 Such<br />

changes not only require policy strategies<br />

geared to providing the type of housing<br />

needed in the future, but also to deliver<br />

suitable transport, services, leisure and<br />

other facilities.<br />

image and economic development<br />

The image and attractiveness of New<br />

Towns has declined, and they are no longer<br />

considered to be the ‘best choice’ for those<br />

who want to live outside the congested<br />

urban areas. People initially moved to the<br />

New Towns because of the quality of the<br />

environment and the lower land prices.<br />

Policies designed to attract the middle<br />

classes through the provision of better<br />

housing and education services have been<br />

successful, but the context has now changed.<br />

The main problem facing New Towns today<br />

is their identity. Rather than becoming real<br />

communities they were simply places to<br />

live and are now generally thought of as<br />

dormitory towns, despite the fact that<br />

employment provision has grown.<br />

Jobs have been created in the New Towns<br />

mainly because of their location close to<br />

large cities. They have attracted businesses<br />

by offering good infrastructure, tax incentives<br />

and facilities. Business parks have been<br />

developed, often around new technology<br />

clusters and innovative industries. Some<br />

towns have attracted more services and hightech<br />

companies (for example Nokia in Espoo);<br />

others have attracted logistical companies.<br />

New Towns have succeeded in providing a<br />

wide range of cultural and leisure activities,<br />

and in most cases residents are encouraged<br />

to participate in the social life of the town to<br />

raise the sense of community. They now face<br />

the difficult task of further strengthening<br />

their economies in a sustainable way to<br />

avoid negative impacts on the quality of<br />

life of their inhabitants and the identity of<br />

the town.<br />

mobility<br />

The New Towns and suburbs have both<br />

experienced a period of rapid growth,<br />

signalling the end of the ‘city’ as a coherent,<br />

architectural and compact territory. They had<br />

to provide services, housing and transportation<br />

from scratch. Transport provision was a crucial<br />

issue because of the distances to the centre<br />

of the core city, but low densities of these<br />

new urban areas did not make it easy to build<br />

functional and efficient infrastructure.<br />

Both in the New Towns and in the periphery,<br />

the planning of infrastructure has not<br />

caught up with urban development. In the<br />

best cases, the demand for transport<br />

between the new urban areas and the<br />

original town centres has been met. While<br />

the master plans for most New Towns<br />

included provisions for lateral connections<br />

with other centres, the available budgets<br />

have generally not been sufficient to deliver<br />

the planned infrastructure. The public<br />

transport links that have been built link the<br />

centre of the metropolitan area to the<br />

periphery via rapid transit, metro and<br />

motorways. Internal rail and bus routes and<br />

links with other areas in the periphery were<br />

not provided; virtually all these journeys are<br />

therefore made by car.

<strong>NovaTerra</strong> <strong>Connected</strong> <strong>Cities</strong> / december 2005 / 7<br />

Milton Keynes is a good example. Its urban<br />

structure is based on a grid and the town<br />

is zoned into separate residential and<br />

industrial blocks, and employment is<br />

dispersed across the town in different<br />

locations. The population density is<br />

extremely low, which means that people<br />

have to travel long distances between<br />

activities. Milton Keynes was specially<br />

designed to cater for easy and fast travel by<br />

car, with plentiful parking and dispersed land<br />

uses, so it is no surprise that the use of public<br />

transport in Milton Keynes is about half the<br />

national average for towns of a similar size.<br />

Changing this situation will require a<br />

considerable increase in public transport<br />

provision and stringent measures to curb car<br />

use. Moreover, the structure of the town,<br />

which is ill suited to the operation of public<br />

transport, and the car culture are major<br />

obstacles that have to be overcome.<br />

Despite these obstacles, Milton Keynes<br />

Council has launched a programme to<br />

stimulate greater use of public transport.<br />

The long-term vision is to increase journeys<br />

by public transport to three to four times<br />

current levels. Given the growth in the<br />

population, this would equate to an increase<br />

in the number of public transport trips per<br />

year from about 7 million now to about 35<br />

to 40 million in 2031. The council is currently<br />

studying the structure of the city and its<br />

suitability for public transport, focusing on<br />

options for Bus Rapid Transit. The need<br />

to reduce dependency on the car is widely<br />

felt and Milton Keynes is just one many<br />

New Towns that aim to improve their<br />

transportation systems.<br />

Jobs have been created<br />

in the New Towns<br />

mainly because of their<br />

location close to the<br />

large cities<br />

The French New Town of Melun-Senart, near Paris.<br />

(photo: Pascaline Gaborit)<br />

towards sustainable new towns<br />

Most New Towns now have a public<br />

transport policy, and many of these propose<br />

better bus or light rail connections, highquality<br />

facilities and frequent services.<br />

In some towns, like Milton Keynes, improving<br />

public transport will require considerable<br />

investment to overcome the problems posed<br />

by the urban structure. In other cases, for<br />

example in France, local authorities are<br />

relying on regional or national decisions to<br />

improve the transport system. Transport<br />

policies for most of the towns are still quite<br />

limited: car use is sometimes still facilitated<br />

through the provision of parking places and<br />

many areas within the New Towns are not<br />

accessible by public transport.<br />

Raising urban densities may be an important<br />

condition for the introduction and use of<br />

more sustainable transport systems. This is<br />

a longer-term goal and will not be easy to<br />

achieve – it would mean developing real<br />

town centres and require further economic<br />

growth and higher local authority budgets.<br />

In the meantime, decision makers in New<br />

Towns have realised two things: increasing<br />

congestion is not an asset for their town; and<br />

they need an alternative public transport<br />

system directed principally at the elderly,<br />

lower-income families and students, but also<br />

to offer viable options for people who do not<br />

want to travel by car every day.<br />

Mobility and transport have implications for<br />

all the other aspects of the New Towns: their<br />

economies, urban planning and governance.<br />

These are global challenges which require<br />

what Stevenage calls the ‘reinvention of the<br />

New Town mindset’. This should seek to<br />

generate wider ownership of the New Town<br />

concept by external stakeholders and focus<br />

on developing the potential of the New<br />

Towns within the wider sub-regional and<br />

regional context.<br />

Notes<br />

1 Jane Hobson, New Towns, the modernist planning<br />

project and social justice: the case of Milton-Keynes<br />

UK, conference lecture about ‘urban development’,<br />

Cairo Egypt, 6th October 1999.<br />

2 Gemeente Spijkenisse, Statistisch jaaroverzicht 2004,<br />

the Netherlands.<br />

References<br />

– JP. Antoni, Urban sprawl modelling: A methodological<br />

approach, in Cybergeo 207, 1 March 2002.<br />

– Akio Doteuchi, The changing face of suburban<br />

New Towns – Seeking the ‘slow life’ for an ultra-aging<br />

society, NLI Social Development Research Group,<br />

October 2003.<br />

– ENTP, Contextual analysis of 6 New Towns, NEWTASC<br />

INTERREG IIIB project.<br />

– Pierre Merlin, New Towns in Perspective, INTA Press,<br />

April 1991.<br />

– Alan Parker, Transport and ecologically sustainable<br />

cities, Town and Country Planning Association<br />

of Victoria, Australia, 2004.<br />

– RTPI News, No sound planning basis for the<br />

development of Milton Keynes, Planning,<br />

June 4, 2004.<br />

– Revue Esprit, La ville à trois vitesses: gentrification,<br />

relegation, périurbanisation, Jacques Donzelot,<br />

March-April 2004 France.<br />

http://www.newtowns.net<br />

Z

<strong>NovaTerra</strong> <strong>Connected</strong> <strong>Cities</strong> / december 2005 / 8<br />

Founded on an understanding of the interrelationships between accessibility, location, design<br />

and intensity of land use, the Transport Development Area concept developed in the UK is a cross-<br />

sectoral mechanism for delivering higher density development around public transport nodes.<br />

The approach unites land use planning and the development industry with transport planning<br />

and transport operators. Urban design, community involvement and active urban management<br />

are key components for a workable package.<br />

Transport Development Areas<br />

Peter Hine, Symonds Group / Jeremy Edge, Knight Frank / Kathy Gal, gal.com / Michael Chambers, RICS<br />

The Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors<br />

(RICS) has been developing the concept of<br />

the Transport Development Area (TDA) with<br />

key stakeholders for a number of years<br />

now. In 2002 RICS published a good practice<br />

guide that provides planning and transport<br />

practitioners with the tools needed to<br />

identify and implement TDAs. 1 The guidance<br />

was sponsored and supported by thirteen<br />

government authorities, professional<br />

institutes and transport organisations. 2<br />

This sponsorship lent significant backing<br />

for implementing the ideas developed in<br />

the guidance. TDAs can be developed in a<br />

wide range of circumstances, ranging from<br />

transport nodes in large conurbations to<br />

relatively small market towns.<br />

In essence, a TDA is a means of securing well<br />

designed, higher density, mixed-use<br />

development around good public transport<br />

nodes in towns and cities. It does not seek<br />

to lay down a rigid blueprint and can be<br />

applied in ways that suit the needs of a<br />

particular location.<br />

It does not require new legislation or<br />

changes in policy, but it does require the<br />

commitment of local authorities and other<br />

partners if the concept is to be carried<br />

forward successfully. TDA is an integrated<br />

land use planning approach to create a more<br />

specific relationship between development<br />

density around urban public transport<br />

interchanges and the level of public<br />

transport services provided. As an economic<br />

concept, TDAs are also a focus for more<br />

institutionalised arrangements whereby<br />

public transport operators receive additional<br />

funding based on the transfer, where<br />

appropriate, of part of the higher financial<br />

returns to development which might be<br />

achievable in such areas. TDAs, therefore, can<br />

deliver significant transport and development<br />

benefits by enabling financially more<br />

attractive (or at least less uncertain)<br />

development opportunities, and by offering<br />

the prospect of additional investment in<br />

public transport improvements. They also<br />

contribute to the sustainability objectives of<br />

the Transport White Papers by integrating land<br />

use and transport, reducing both the need to<br />

travel and reliance on private transport.<br />

the tda approach<br />

The basic concept of the ‘TDA Approach’ is<br />

already recognised within the existing policy<br />

framework. However, our research found<br />

Opportunity diagram<br />

that the approach to identifying and<br />

implementing TDA-style development of key<br />

sites or locations within urban areas has<br />

been both inadequate and inconsistent.<br />

While the planning system can and does<br />

deliver TDA-style development, benefits<br />

can be gained from greater clarity or more<br />

positive direction at the policy level, and<br />

from the provision of detailed guidance on<br />

TDA identification and delivery.<br />

Securing widespread application of the<br />

TDA Approach across a range of urban<br />

circumstances will require commitment by<br />

all stakeholders. The RICS guidance sets out<br />

the practical mechanisms for designating<br />

and delivering TDAs and the policy process<br />

that will be needed from the national to local<br />

planning level. The key messages in the<br />

guidance are that TDAs should be a key focus<br />

of locational policy, the TDA Approach is a

<strong>NovaTerra</strong> <strong>Connected</strong> <strong>Cities</strong> / december 2005 / 9<br />

mechanism for delivering suitable outcomes,<br />

and that long-term planning is essential.<br />

Although the concept of concentrating<br />

development around appropriate transport<br />

nodes is not new, it is difficult to realise<br />

successfully because many different<br />

elements need to be brought together to<br />

make it work. TDAs are not a quick fix,<br />

but early action can be taken.<br />

The TDA approach is not exclusively meant<br />

for the United Kingdom. It can work in many<br />

different situations throughout Europe.<br />

The following discussion of the UK situation<br />

serves only to illustrate the relation between<br />

TDA and national, regional and local policy<br />

frameworks. The underlying principles<br />

remain the same for other countries.<br />

regional guidance<br />

There is considerable scope for the new<br />

Regional Spatial Strategies being developed<br />

within the UK to take account of the TDA<br />

TDA Linkages<br />

approach and promote its inclusion within<br />

more local planning frameworks and local<br />

transport plans. TDAs should be actively<br />

promoted as a regional objective, to be<br />

applied across as wide a range of urban<br />

settlement types and rural centres as<br />

possible. It is vital to the approach that key<br />

stakeholder groups, such as the transport<br />

providers and the development industry,<br />

are engaged at an early stage.<br />

Where appropriate, Regional Spatial<br />

Strategies should encourage local authorities<br />

to ensure that within TDAs permissions for<br />

higher density development include<br />

developer contributions towards public<br />

transport and local transport objectives. The<br />

Regional Transport Strategy – prepared as an<br />

integral part of regional spatial planning –<br />

should include measures relevant to TDAs,<br />

such as accessibility criteria, increased public<br />

transport choice, car parking standards and<br />

demand management.<br />

The London Plan – the first spatial<br />

development strategy in the UK – indicates<br />

that designation of sites for TDA-style<br />

development should be undertaken by the<br />

various London boroughs, with the London<br />

Plan itself providing appropriate policy<br />

advice and characterising the key<br />

opportunities across Greater London.<br />

Local authorities should seek to make<br />

maximum use of the most accessible sites,<br />

such as those in town centres and others<br />

which are, or will be, close to major transport<br />

interchanges. They should develop a clear<br />

vision for development of these areas,<br />

prepare site briefs and, where appropriate,<br />

consider using compulsory powers to bring<br />

development forward. The TDA Approach<br />

supports Government policies designed to<br />

promote both urban and rural regeneration,<br />

with access to key services and facilities<br />

delivered through integrated local transport<br />

solutions.<br />

Y

<strong>NovaTerra</strong> <strong>Connected</strong> <strong>Cities</strong> / december 2005 / 10<br />

survey, analysis, plan<br />

At the pre-deposit consultation stage,<br />

structure plans and local development<br />

frameworks should incorporate as a specific<br />

objective the promotion of TDAs as a focus for<br />

locational policy to be applied across a range<br />

of urban settlement types and rural centres.<br />

Key sites and central locations will normally<br />

be the most appropriate for formal TDA<br />

designation. Other locations such as nodal<br />

points and interchanges on main public<br />

transport routes, however, will readily lend<br />

themselves to adoption of the underlying<br />

principles. Local authorities should apply the<br />

TDA approach in three key phases: survey,<br />

analysis and plan-making. Knowledge about<br />

the likely locations of TDAs is crucial. Local<br />

authorities should keep a number of factors<br />

under review. First, the principal physical and<br />

economic characteristics of the area,<br />

including supply and demand in the real<br />

estate market as well as the size,<br />

composition and distribution of population.<br />

The communications, transport system and<br />

traffic in the area should be considered, as<br />

well as the environmental characteristics.<br />

Finally, we should not overlook overall<br />

accessibility appraisal, including the transport<br />

network, service levels, network capacity and<br />

scope for expansion.<br />

The survey phase will identify likely locations<br />

with the potential to adequately serve more<br />

intensive land use developments and<br />

markets able to promote and support such<br />

development. The analysis stage should<br />

consider significant excess capacity in<br />

existing infrastructure, including public<br />

transport, utilities and social infrastructure.<br />

It should look at the potential for<br />

development in existing or new public<br />

transport corridors. And it has to identify<br />

opportunities for improving public transport<br />

accessibility.<br />

Early discussion and liaison between local<br />

authorities, developers, landowners,<br />

operators, the Regional Development<br />

Authorities (RDAs), Local Enterprise<br />

Companies (LECs), the Welsh Development<br />

Agency and all other stakeholders is essential<br />

to the successful application of the TDA<br />

Approach, with development frameworks<br />

TDA Management Company Model<br />

and local transport plans providing the initial<br />

basis for this. Local planning authorities<br />

should prepare appropriate TDA-related<br />

policies and proposals, taking particular<br />

account of boundaries, transport<br />

accessibility appraisals, urban design,<br />

density, parking standards and other key<br />

issues. Planning frameworks should identify<br />

key criteria relevant to the TDA Approach,<br />

particularly in relation to transport<br />

accessibility and urban design. Major TDA<br />

development opportunities should be<br />

supported by a detailed design or<br />

development brief including, where<br />

appropriate, boundaries and density ranges<br />

(particularly for residential development).<br />

Implementing the TDA Approach The key<br />

ingredients for successful implementation<br />

of the TDA Approach are the establishment<br />

of an overall partnership, funding, land<br />

assembly, a specific delivery mechanism and<br />

on-going monitoring and review.<br />

Partnerships<br />

The most complex schemes may benefit from<br />

forming TDA delivery companies to secure<br />

implementation, delivery and management.<br />

Government regeneration policy underlines<br />

the need to secure an Urban Renaissance<br />

through effective partnerships. These should<br />

allow ‘joined-up strategies’ to be developed<br />

with local people and other organisations<br />

and interests involved to tackle local<br />

problems and realise local opportunities.<br />

Partnerships formed to take the TDA<br />

Approach forward should include the local<br />

authority, normally in the lead or enabling<br />

role, landowners, investors, developers,<br />

designers, transport operators/providers and<br />

occupiers. TDA development may involve<br />

developer contributions to public transport<br />

infrastructure, but this will vary greatly<br />

according to local circumstances and the<br />

economic viability of individual schemes<br />

within the TDA.

<strong>NovaTerra</strong> <strong>Connected</strong> <strong>Cities</strong> / december 2005 / 11<br />

Prime Minister Tony Blair and Deputy Prime Minister John Prescott visit Greenhithe in Kent.<br />

(Source: Office of the Deputy Prime Minister)<br />

Land assembly<br />

Land assembly will often be an important<br />

issue for TDA-type development, particularly<br />

for large development sites. Many parties<br />

may hold land within a potential TDA and<br />

land ownership surveys need to be<br />

undertaken by the TDA promoter at an early<br />

stage. In some cases the use of, or threat of<br />

the use of, compulsory purchase will be<br />

necessary for planning authorities to secure<br />

the TDA development within appropriate<br />

boundaries. However, in most cases<br />

agreement between all landowning<br />

stakeholders should be the objective.<br />

Active urban management<br />

Much of the advantage to be gained through<br />

the TDA Approach will be squandered unless<br />

an appropriate regime of on-going active<br />

urban management is put in place. Town<br />

Improvement Schemes are a potential<br />

mechanism for allowing local authorities<br />

and other stakeholders to deal with area<br />

improvement and maintenance of<br />

environmental quality. The concept may<br />

prove to be of particular importance with<br />

regard to TDAs, along with appropriate joint<br />

ventures and/or partnership agreements.<br />

tdas in action<br />

Since RICS published its guidance report,<br />

the TDA project has continued to attract wide<br />

support from a range of diverse groups,<br />

including the Local Government Association,<br />

the Royal Institution of British Architects, the<br />

Greater London Authority, Scottish Enterprise<br />

and the Institution of Highways and<br />

Transportation. While these organisations<br />

recognise the benefits of TDAs, others have<br />

been implementing them in practice. The RICS<br />

guidance contains a wealth of case studies<br />

from locations throughout the country. These<br />

cover TDAs at town, city and even up to county<br />

level. Spatial strategies for regions such as<br />

London and South East England have focussed<br />

heavily on the need to produce ‘well-designed,<br />

higher density, mixed-use areas, situated<br />

around good public transport access points in<br />

urban areas’. Recognising the important<br />

leadership role that London can play, RICS<br />

published further research in 2003 that<br />

looked at how TDAs could be developed<br />

further in London. 3 The study found that TDAs<br />

have the capability of delivering many<br />

of the London Plan’s key objectives, from<br />

affordable housing to transport<br />

improvements and urban regeneration.<br />

Sustainable communities<br />

‘Sustainable communities’ has rapidly<br />

become the new buzz phrase in UK planning.<br />

Virtually every consultation paper or report<br />

issued by the Office of the Deputy Prime<br />

Minister now has the ‘sustainable<br />

communities’ strapline. This may be an<br />

excellent marketing strategy, but there is a<br />

danger that the constant repetition of the<br />

sustainable communities mantra and the<br />

multiple ways in which the term is<br />

interpreted will, in the end, leave it devoid of<br />

meaning. That would be a pity because the<br />

concept, however it is interpreted, is<br />

intrinsically sound. The UK Government<br />

launched its Sustainable Communities Plan<br />

in February 2003 with the avowed objective<br />

of creating ‘prosperous, inclusive and<br />

sustainable communities’. From an RICS<br />

perspective, some of the key priorities<br />

should be:<br />

– locating new housing and commercial<br />

development in the most sustainable<br />

places;<br />

– providing the infrastructure needed to<br />

support communities;<br />

– socially inclusive policies in housing that<br />

create balanced communities;<br />

– regeneration policies that are sensitive to<br />

local communities’ needs and reflect the<br />

‘soul’ of an area;<br />

– strategies for areas in decline as well as<br />

growth areas in the South East.<br />

Transport-oriented development Through<br />

its work on TDAs, RICS has argued that the<br />

successful integration of land use and<br />

transport can play a key role in reducing many<br />

of the difficulties posed by modern urban<br />

development. The orientation of integrated<br />

economic and residential activities around<br />

public transport nodes and the creation<br />

of relatively self-reliant sub-centres within<br />

wider metropolitan areas are important<br />

factors in reducing the need to travel and<br />

encouraging the use of more sustainable<br />

public transport modes. The TDA good<br />

practice guide has demonstrated the benefits<br />

that can be gained from providing highdensity,<br />

high-quality, mixed-use development<br />

around transport nodes. Testing this approach<br />

in London and the Thames Gateway3 will be<br />

the focus of the Greater South East activities<br />

within the <strong>Connected</strong> <strong>Cities</strong> project.<br />

Notes<br />

1 Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors, Transport<br />

Development Areas – Guide to Good Practice, London,<br />

2002.<br />

2 The Greater London Authority; the Institution of<br />

Highways and Transportation; the Institute of<br />

Logistics and Transport; LT Property; the Local<br />

Government Association; Railtrack Property; the<br />

Royal Institute of British Architects; the Royal Town<br />

Planning Institute; Scottish Enterprise; the Strategic<br />

Rail Authority; Strathclyde Passenger Transport<br />

Executive; Transport for London; and the RICS London<br />

Regional Board.<br />

3 TDAs – the London dimension, april 2003, RICS<br />

London Region. See also www.rics.org<br />

Z

<strong>NovaTerra</strong> <strong>Connected</strong> <strong>Cities</strong> / december 2005 / 12<br />

The European Spatial Development<br />

Perspective proposes creating several<br />

dynamic zones of global economic<br />

integration and a network of<br />

internationally accessible metropolitan<br />

regions. Such a vision can only become<br />

reality by complementing international<br />

and national hubs with regional and<br />

local growth opportunities. How is this<br />

vision applied to the Thames Gateway<br />

Regeneration Corridor in the Greater<br />

South East region of England?<br />

Sustainable development and growing mobility in the South East of England<br />

Connecting<br />

the Greater South East<br />

Arno Schmickler, South East England Development Agency (SEEDA), Guildford, UK<br />

Illustrations: SEEDA (unless indicated otherwise)<br />

The region around London in the South East<br />

of England is home to about 21 million people<br />

living on only 16% of the total UK territory.<br />

This economic powerhouse creates 42% of<br />

the UK’s gross value added1 and many global<br />

headquarters are located in this area. Key<br />

international gateways, such as Heathrow<br />

Airport, Southampton and Felixstowe<br />

seaports and the Channel Tunnel provide<br />

access to London as one of three world<br />

cities. 2 Strictly speaking, London itself is only<br />

a small but very important part of Greater<br />

London; Greater London consists of the City<br />

of London, the City of Westminster and 31<br />

other London boroughs. In order to better<br />

understand and reflect the intrinsic relation<br />

between London and its surrounding region,<br />

three Regional Development Agencies have<br />

recently joined forces in the Greater South<br />

East super-region, including Greater London,<br />

the East of England and the South East<br />

England regions.<br />

accommodating growth in the greater<br />

south east<br />

Major population growth needs to be<br />

accommodated within the Greater South<br />

East. London itself is expected to grow from<br />

currently 7.4 million inhabitants to 8 million<br />

by 2016, and further growth will take place in<br />

the East and South East. To respond to this<br />

challenge the Office of the Deputy Prime<br />

Minister (ODPM) launched the Creating<br />

Sustainable Communities plan in 2003. This<br />

document sets out policies, resources and

<strong>NovaTerra</strong> <strong>Connected</strong> <strong>Cities</strong> / december 2005 / 13<br />

partnerships to achieve a step change in<br />

the Government’s approach to tackling ‘the<br />

challenges of a rapidly changing population,<br />

the needs of the economy, serious housing<br />

shortages in London and the South East and<br />

the impact of housing abandonment in<br />

places in the North and Midlands’. 3<br />

The Creating Sustainable Communities<br />

programme aims to take pressure off London<br />

through the provision of 250,000 new homes<br />

in the South East. These new homes will<br />

mainly be located in four growth areas:<br />

Thames Gateway, Ashford, Milton Keynes-<br />

South Midlands and London-Stansted-<br />

Cambridge. Alongside housing growth, an<br />

extra 120-180,000 jobs in the Thames<br />

Gateway and 120-150,000 in Milton Keynes-<br />

South Midlands are envisaged by 2016 as a<br />

key component of the programme.<br />

Delivery of the Sustainable Communities<br />

programme can only be achieved by<br />

interdisciplinary and cross-sectoral working.<br />

The UK Planning Policy Guidance on<br />

Transport 4 makes the case for a switch away<br />

from reliance on the private car and urban<br />

dispersal towards more sustainable modes of<br />

travel and urban growth. The key principles<br />

outlined in this guidance are important<br />

preconditions for urban renaissance and the<br />

delivery of the Sustainable Communities<br />

plan. They include promoting more<br />

sustainable transport choices and reducing<br />

the need to travel; promoting social inclusion,<br />

in part by revitalising towns and cities as<br />

places to live and work; focusing major<br />

generators of travel demand in urban areas<br />

near to public transport; giving more road<br />

space to pedestrians and cyclists, and giving<br />

priority to people over traffic in towns.<br />

a polycentric mega-city region<br />

The Greater London area is undergoing a<br />

process of decentralised concentration –<br />

concentration on a global scale (global cities)<br />

with simultaneous decentralisation and<br />

suburbanisation at the regional and local<br />

scales. The ever increasing mobility of people<br />

and goods in particular presents a challenge<br />

to urban cohesion. Not only transport<br />

technologies but also information and<br />

communication technologies have altered<br />

South East England: Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty, Green Belt land and the Growth Areas.<br />

Source: Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, Creating sustainable<br />

communities: Making it happen, Thames Gateway and the Growth Areas,<br />

London 2003, p.7<br />

settlement structures. The combination of<br />

both – transport and communication<br />

technologies – is leading to a new correlation<br />

between space and time, and hence to<br />

fundamental changes in the relationship<br />

between the city and the region. 5<br />

In particular, transport technologies have<br />

enabled a transformation of resident<br />

communities into itinerant communities: an<br />

ever increasing number of people understand<br />

themselves to be global commuters in a digital<br />

market place. Castells introduced the concepts<br />

of the ‘network society’ and ‘informational<br />

capitalism’ to describe this process. 6<br />

Within a region like South East England the<br />

challenge is to better utilise the existing<br />

infrastructure and to encourage people to<br />

use public transport by improving the quality<br />

of the travel environment. The existing<br />

infrastructure, however, was mainly<br />

developed for the purpose of serving industry<br />

and followed the planning ideal of separating<br />

functions; for example, the rail network in the<br />

Greater South East is London-centric to<br />

accommodate historic commuting patterns<br />

from the urban fringe to the core city. This<br />

segregation of functions and socio-spatial<br />

fragmentation can be seen as the peak of the<br />

planning ideal of the industrial age (Fordism).<br />

But this ideal loses its strength when<br />

economic growth, as well as scientific and<br />

social progress, begins to demand a higher<br />

integration of functions and a more<br />

sustainable approach to dealing with scarce<br />

resources. Urban and regional planning,<br />

therefore, needs to adapt mechanisms as<br />

well as the built environment and its<br />

infrastructure to the needs and requirements<br />

of post-industrial regions.<br />

To achieve this change it is important to<br />

understand the economic and community<br />

relations within the region and beyond.<br />

A vital aspect of this is recognising the<br />

interdependency of London and the South<br />

East to keep the region on a successful track:<br />

the global city of London relies on the South<br />

East and vice versa. For London to be a global<br />

hub and to continue creating the economic<br />

power needed for the whole country – and for<br />

Europe – it is crucial to counterbalance the<br />

regional economies around those hubs<br />

(economic equilibrium). In this context the<br />

concept of a polycentric mega-city region<br />

needs to be looked at in more detail.<br />

spatial and functional polycentricity<br />

The European Spatial Development<br />

Perspective (ESDP) argues for polycentric<br />

spatial development and a new urban-rural<br />

relationship. 7 The ESDP also calls for the<br />

Y

<strong>NovaTerra</strong> <strong>Connected</strong> <strong>Cities</strong> / december 2005 / 14<br />

creation of several dynamic zones of global<br />

economic integration and a network of<br />

internationally accessible metropolitan<br />

regions with an integrated hinterland – areas<br />

like the Greater South East England. The<br />

question that arises is how these zones of<br />

global economic integration develop in terms<br />

of their spatial and functional organisation.<br />

Recent research carried out in the Interreg<br />

IIIB NWE POLYNET project led by the Young<br />

Foundation studied eight European megacity<br />

regions in North Western Europe: South<br />

East England, Rhine-Main, Rhine-Ruhr, Bassin<br />

Parisien, European Metropolitan Region<br />

Northern Switzerland, Central Belgium,<br />

Greater Dublin and the Randstad. POLYNET<br />

emphasised that polycentricity is not only<br />

scale-dependent, but also that there is a very<br />

clear distinction to be made between spatial<br />

and functional polycentricity. One activity of<br />

the project focused particularly on businessto-business<br />

communication (virtual as well<br />

as physical/f-2-f) in advanced producer<br />

services in order to map spatial and<br />

functional polycentricity in the study<br />

regions. 8<br />

Based on this extensive quantitative and<br />

qualitative research, POLYNET defined 51<br />

functional urban regions (FURs) in the<br />

Greater South East. FURs ‘comprise a core<br />

defined in terms of employment size and<br />

density, and a ring defined in terms of regular<br />

daily journeys (commuting) to the core’. 9<br />

Thirty FURs are located to the west of London<br />

and only eighteen to the east – this illustrates<br />

a greater dependency of the east on London<br />

and is an indicator of an increasing east-west<br />

imbalance. While the idea of strengthening<br />

regional economies should in principle lead<br />

to an economic equilibrium, there are still<br />

(and will always be) factors favouring certain<br />

locations above others. In the Greater South<br />

East the Western Corridor is economically<br />

very successful and buoyant (Thames Valley<br />

economy), whereas the Thames Gateway<br />

regeneration corridor in the East is struggling<br />

to realise some mixed-use development that<br />

would include higher-order businesses. This is<br />

why workers from the Thames Gateway still<br />

generally commute to business locations in<br />

Canary Wharf or the City of London.<br />

connecting higher density with<br />

higher quality<br />

Some key spatial policy questions can be<br />

derived from the polycentric development<br />

pattern in the Greater South East. How<br />

should policy respond to the increasing eastwest<br />

imbalance? Current public funding is<br />

very much aimed at the east and north of<br />

London to achieve a shift of gravity in the<br />

Greater South East region – will the market<br />

follow the funding? And how can a shift to<br />

more sustainable modes of transport be<br />

achieved? Advanced functional polycentricity<br />

creates orbital and tangential movement<br />

patterns that are no longer dependent on a<br />

core city. Very often these movements cannot<br />

be accommodated by public transport using<br />

existing infrastructure networks that are<br />

centred on a core city; as a result the private<br />

car becomes an even more predominant<br />

mode of transport.<br />

To respond to these challenges, changes in<br />

policy and subsequent implementation are<br />

needed. Decoupling gross domestic product<br />

from transport growth was formally<br />

introduced onto the European agenda at the<br />

Gothenburg Council in 2001, adding the<br />

environmental dimension to the Lisbon<br />

South East England: Functional Urban Regions.<br />

Source: POLYNET report, Action 1.1 SE England, p.3<br />

agenda. This policy is of particular<br />

importance for developing the Greater South<br />

East, where the existing transport networks<br />

are being put under extremely high<br />

pressures. Sustainable transport and a shift<br />

from the private car to other modes of<br />

transport are at the heart of the Gothenburg<br />

Council and subsequent national/regional<br />

policies to address climate change and reduce<br />

greenhouse gas emissions (Kyoto targets).<br />

Together with the ESDP’s goal of develop<br />

dynamic, attractive and competitive cities<br />

and urbanised regions, providing a parity of<br />

access to infrastructure and knowledge,<br />

these aims can only be achieved by concerted<br />

action. Such a vision can only become reality<br />

by complementing international and national<br />

hubs with regional and local growth<br />

opportunities, particularly in locations that<br />

can provide sustainable mobility – in other<br />

words, public transport hubs. In tackling the<br />

challenge of building sustainable urban<br />

spaces in growing metropolitan regions, we<br />

need to ensure that future growth is achieved<br />

with the maximum possible social cohesion<br />

and protection of the environment. More<br />

self-contained urban areas can help to reduce<br />

commuting and bring about mixed

<strong>NovaTerra</strong> <strong>Connected</strong> <strong>Cities</strong> / december 2005 / 15<br />

communities, but the integration of land use<br />

planning and transport is also essential to<br />

deliver that vision.<br />

The aim of achieving higher densities<br />

around public transport hubs needs to be<br />

accompanied by high quality urban and<br />

architectural design. Higher density should<br />

not only be financially more attractive for<br />

investors but also provide a higher quality of<br />

life and support more sustainable patterns of<br />

development. This comes close to the<br />

American practice of Transit Oriented<br />

Development (TOD) or the idea of Transport<br />

Development Areas (TDAs) that the Royal<br />

Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) has<br />

been developing with key stakeholders for a<br />

number of years. 10<br />

Concentrating development and integrating<br />

land use and transport have also been<br />

identified as key actions to assist the Urban<br />

Renaissance agenda in England. ‘In England,<br />

urban areas provide for 91% of the total<br />

economic output and 89% of all the jobs.<br />

Maintaining and improving the economic<br />

strength of our towns and cities is therefore<br />

critical to the competitive performance of the<br />

country as a whole. 11 The potential for change<br />

is limited since ‘more than 90% of our urban<br />

fabric will still be with us in 30 years time.’ 12<br />

Therefore the quality of new developments is<br />

decisive to achieve the step change towards<br />

building a sustainable urban environment.<br />

‘Successful urban regeneration is designled.’<br />

13<br />

the thames gateway growth area<br />

Within the Greater South East substantial<br />

public funding is being channelled into the<br />

Thames Gateway, a major regeneration<br />

corridor. A great challenge for this area is to<br />

avoid becoming a cluster of dormitory towns<br />

for people commuting into London. Therefore<br />

it is important to strengthen locally<br />

distinctive patterns of culture and integrate<br />

mixed functions. In the context of large<br />

mega-city regions, it is vital for small and<br />

medium-sized towns to build upon their<br />

intrinsic local potential and develop an<br />

identity. A clear vision is needed which<br />

complements rather than duplicates existing<br />

or emerging urban patterns in polycentric<br />

city regions. The contribution small and<br />

medium-sized towns can make to a larger<br />

city region goes well beyond providing cheap<br />

housing within easy commuting distance to<br />

employment centres. Particularly in times<br />

when the pressures resulting from the core<br />

city are increasing – both in terms of demand<br />

for housing and employment land – it is<br />

important to carefully mature the concept of<br />

a network of complementary small and<br />

medium-sized towns. 14<br />

The Thames Gateway already has an<br />

established history, beginning with the<br />

development of the Docklands area. The<br />

benefits of Canary Wharf and the Isle of<br />

Dogs in London are becoming visible and<br />

accountable some 25 years after strategic<br />

decisions were made. With the shift in focus<br />

to the east, London is aiming to regenerate<br />

major areas of previously developed land and<br />

to provide space for further growth. The<br />

proposals for Olympia 2012, with the main<br />

facilities to be built in the east of London<br />

centred around the new high-speed train<br />

station to be opened in Stratford, underpins<br />

the new role of the Thames Gateway. But the<br />

Thames Gateway extends well beyond the<br />

boundaries of London.<br />

regeneration needs<br />

The Government has not defined this<br />

regeneration corridor along administrative<br />

boundaries but by regeneration needs,<br />

including large areas of derelict land and<br />

deprived communities. The Thames Gateway<br />

is an area of approximately 80,000 hectares<br />

in size, measuring 65 kilometres long and up<br />

to about 30 kilometres wide. It contains<br />

about 700,000 households and is home to<br />

around 1.6 million people and provides about<br />

500,00 jobs. 15<br />

The Thames Gateway offers the greatest<br />

development opportunities in the South East,<br />

together with the major concentration of<br />

previously developed land and deprivation in<br />

the country. It has the potential to deliver<br />

around 120,000 new homes and 200,000<br />

new jobs by 2016, subject to the appropriate<br />

physical and social infrastructure being in<br />

place. The Gateway will play a key part in<br />

delivering sustainable growth for South East<br />

England. As it has the largest collection of<br />

previously developed land (3000 hectares)<br />

near any European capital city it represents a<br />

major opportunity to address the housing<br />

shortage without large-scale release of green<br />

belt land. 16<br />

rail catalyst<br />

The high-speed Channel Tunnel Rail Link<br />

(CTRL), with its international passenger<br />

stations in Ashford, Ebbsfleet, Stratford and<br />

King’s Cross/St Pancras, can be seen as a<br />

prime regeneration catalyst in this corridor.<br />

Together with other major regional transport<br />

investments, such as Crossrail and Fastrack,<br />

CTRL will transform accessibility for the<br />

Thames Gateway area. An important<br />

precondition for delivering the sustainable<br />

communities in the Thames Gateway is the<br />

understanding that this large-scale<br />

development cannot be served purely by carbased<br />

transport system. New river crossings<br />

are being designed to accommodate multimodal<br />

traffic, making room for light rail and<br />

bicycle connections. Of strategic importance<br />

here are two new Thames crossings near the<br />

Royal Docks (Gallions Crossing) and near<br />

Thurrock (Lower Thames Crossing). The latter<br />

in particular will divert traffic from the<br />

Channel ports away from the congested<br />

South East region and the M25, leading it<br />

directly north, circumnavigating London<br />

completely.<br />

five strategic development locations<br />

Within the Thames Gateway development<br />

is focused on five strategic development<br />

locations: 17<br />

1 The East London Gateway, particularly<br />

around Stratford and the Lower Lea Valley,<br />

accommodating the development needed<br />

to make the London Olympics in 2012 a<br />

success and building on the good existing<br />

transport infrastructure.<br />

2 The area south of the Thames from<br />

Greenwich Peninsula to Woolwich, where<br />

there is potential for 20,000 new homes,<br />

developing the former Woolwich Arsenal<br />

site and including a new use for the Dome<br />

site with its successful Millennium<br />

Community. Y

<strong>NovaTerra</strong> <strong>Connected</strong> <strong>Cities</strong> / december 2005 / 16<br />

3 The area north of the Thames at Barking<br />

Reach – London’s largest area of previously<br />

developed land.<br />

4 Thurrock Riverside, with a substantial<br />

development potential for employment<br />

land, incorporating the Port of London and<br />

the proposal for a new container port at<br />

Shellhaven.<br />

5 North Kent Thamesside around Ebbsfleet<br />

International Passenger Station and the<br />

Medway Estuary.<br />

Further housing and employment will be<br />

allocated to key locations in the Gateway,<br />

such as Medway, Southend, Basildon and<br />

Sittingbourne-Sheerness.<br />

sustainable growth through partnership<br />

The key to delivering government targets<br />

in a sustainable way is the partnership<br />

approach. Neither political configurations nor<br />

individual budgets are equipped to deal with<br />

regeneration on such a large, strategic scale.<br />

The fact that the public sector input is<br />

achieved at all levels, from local authority<br />

to a specifically dedicated government<br />

department, ensures ‘joined-up’ policy<br />

changes and development implementation.<br />

This direct and coordinated public sector<br />

approach visibly encourages the private<br />

sector to begin to invest considerable<br />

resources in an area which otherwise fails to<br />

attract private sector interests. In all<br />

undertakings in the Thames Gateway, risks<br />

have to be taken and initial costs for<br />

remediation of previously used land are high.<br />

However, an extremely tight Green Belt policy<br />

and government direction on reusing<br />

previously developed land offers the private<br />

sector a real incentive to look at building on<br />

recycled land. A relaxation of that policy for<br />

the sake of achieving higher development<br />

profits would ultimately lead to the failure of<br />

the Urban Renaissance agenda. Tackling<br />

major contamination and pollution issues,<br />

addressing social problems, unemployment,<br />

crime and vandalism, and recharging former<br />

industrial sites with the value of aesthetics<br />

by using the rich history can change<br />

perceptions and enable the disjointed<br />

communities to reintegrate into the socioeconomic<br />

fabric of urban society. Integration<br />

The Thames Gate<br />

South East England: Functional Urban Regions.<br />

Source: POLYNET report, Action 1.1 SE England, p.3<br />

of commercial and residential use rather than<br />

segregation, provision of community services<br />

and parks, promotion of sustainability in<br />

terms of recycling and building efficiency, and<br />

encouraging high quality design will make a<br />

difference to the existing urban environment<br />

in the Thames Gateway.<br />

Notes<br />

1 National Statistics, 22 December 2004, www.<br />

statistics.gov.uk.<br />

2 Saskia Sassen, <strong>Cities</strong> in a world economy, Thousand<br />

Oaks Ca., 1994.<br />

3 Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, Sustainable<br />

communities: Building for the future, London,<br />

2003, p.2.<br />

4 Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, Planning Policy<br />

Guidance 13: Transport (PPG 13), London, 1994.<br />

5 See: Arno Schmickler, From commuterland to regional<br />

citizenship. South East England – A growing region in<br />

Europe, in: Christ, Wolfgang & Martin Fladt, Jahrbuch<br />

der Modellprojekte 2003 / 2004, Weimar, 2004.<br />

6 Manuel Castells, The rise of the network society,<br />

Cambridge, 1996.<br />

7 European Commission, ESDP – European Spatial<br />

Development Perspective. Towards balanced and<br />

sustainable development of the territory of the<br />

European Union, Luxembourg, 1999, p.11.<br />

8 POLYNET project reports edited by Sir Peter Hall and<br />

Dr Kathryn Pain, The Young Foundation, London<br />

2004/05, www.icstudies.ac.uk/html/whatdo_A.asp<br />

9 POLYNET Action 1.1, Summary report, p.2.<br />

10 Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors, Transport<br />

Development Areas – Guide to Good Practice,<br />

London, 2002.<br />

11 Urban Task Force, Towards an urban renaissance: Final<br />

report of the Urban Task Force chaired by Lord Rogers<br />

of Riverside, London, 1999, p.32.<br />

12 Urban Task Force, Towards an urban renaissance: Final<br />

report of the Urban Task Force chaired by Lord Rogers<br />

of Riverside, London, 1999, p.113.<br />

13 Urban Task Force, Towards an urban renaissance: Final<br />

report of the Urban Task Force chaired by Lord Rogers<br />

of Riverside, London, 1999, p.49.<br />

14 See: Detlef H. Golletz & Arno Schmickler, From spaces<br />

to places. Enabling Sustainable urban growth in South<br />

East England with a practical focus on the<br />

Queenborough-Rushenden Zone of Change, in:<br />

Bundesamt für Bauwesen und Raumordnung, Kleinund<br />

Mittelstädte in Stadtregionen. Informationen zur<br />

Raumentwicklung, Heft 8, Bonn, 2005.<br />

15 Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, The Thames<br />

Gateway, London, 2004.<br />

16 Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, Creating<br />

sustainable communities: Making it happen: Thames<br />

Gateway and the Growth Areas, London, 2003.<br />

17 Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, Creating<br />

sustainable communities: Making it happen: Thames<br />

Gateway and the Growth Areas, London, 2003. Z

<strong>NovaTerra</strong> <strong>Connected</strong> <strong>Cities</strong> / december 2005 / 17<br />

Rotterdam Blaak station.<br />

Going underground:<br />

light, air and space!<br />

Building underground is becoming more common. For transport infrastructure and retail, commercial and<br />

leisure functions, underground spaces can offer surprising advantages – and save money. Design and<br />

safety are key components in making underground facilities successful. Inge van Berkel of the Netherlands<br />

Centre for Underground Construction reviews the case for going below ground.<br />

Inge van Berkel, Netherlands Centre for the Underground Construction (COB), Gouda<br />

Photos: Netherlands Centre for the Underground Construction (COB), Gouda<br />

During an unexpected diversion on the Rotterdam metro I passed<br />

Beurs, Oostplein, Voorschoterlaan, Gerdesiaweg and Capelsebrug<br />

stations. For me and my fellow stranded train passengers, the<br />

alternative metro routes were well signposted and clear, and the<br />

brightly lit stations soon cleared up my morning sleepiness. But at<br />

Kralingse Zoom it was suddenly much darker; here the station is<br />

above ground and the day was still dawning. The next day a lorry<br />

crashed into a metro train further up the same stretch of line. These<br />

two experiences in one week do not seem to fit our expectations<br />

about the underground. The benefits of going underground often<br />

go unnoticed.<br />

More and more developments are going underground. Not<br />

everywhere, but where land is in great demand. Economics and safety<br />

are the main reasons. Countless examples already exist: dwellings<br />

wholly or partly underground, offices, tunnels for all possible modes<br />

of transport, car parks, public records and archives, museums and<br />

water storage facilities. They all show that the restrictions on working<br />

underground can be exploited to raise quality. Many examples can be<br />

found in a book published in 2002 by the Netherlands Centre for<br />

Underground Construction (COB), 1 which showcases buildings that<br />

could never have been built above ground, such as the Guggenheim<br />

Museum in Salzburg, a museum without an exterior but with a<br />

uniquely sculptured interior – a work of art in itself.<br />

extra value for money<br />

The benefits of going underground can be counted in euros<br />

recovered per square metre. Making double use of the land returns<br />

a profit, once the initial investments costs have been written off.<br />

The underground functions free up space above ground for a range<br />

Y

<strong>NovaTerra</strong> <strong>Connected</strong> <strong>Cities</strong> / december 2005 / 18<br />

of other activities, from intensive uses, such as homes and offices<br />

(above underground car parks, for example) to more extensive<br />

activities, such as boulevards and wildlife sites/nature parks.<br />

The extra benefits in these cases comes from the above-ground uses<br />

or combination of uses. Value added can be measured in terms of<br />

improved quality, too. Under certain conditions the underground<br />

element creates a multiplier effect: a successful underground<br />

function can become an attraction in itself and generate increased<br />

flows of shoppers, for example, or museum-goers. Examples include<br />

the much talked about Koopgoot in Rotterdam, the Souterrain in<br />

The Hague and the Beelden aan Zee museum in Scheveningen.<br />

The central theme of <strong>Connected</strong> <strong>Cities</strong> – sustainable solutions for<br />

transport nodes – can be given added value by making innovative<br />

and inspired use of the underground space.<br />

The underground environment creates opportunities not possible<br />

above ground. As Lao Tse pointed out, ‘Architecture is what is left<br />

when you take away the walls.’ Designers of underground places are<br />

faced with a challenging task: in essence, to design the inner and<br />

underground ‘outer’ spaces together in a way that creates a safe,<br />

well-organised and attractive experience. These are the most widely<br />

used ways to raise quality:<br />

– Daylight access: the Artez Hogeschool voor de Kunsten (HKU<br />

University of Professional Education) in Arnhem, the underground<br />

office extension to a historic building on the Maliebaan in Utrecht,<br />

Rotterdam Blaak<br />

station.<br />

the Koopgoot in Rotterdam and the Louvre in Paris, to name just a<br />

few. ‘Light, sightlines and legibility are the three fundamental<br />

principles that underpin the layout of the underground space.’ 2<br />

– Use of materials: the Beelden aan Zee museum in Scheveningen,<br />

the Souterrain in The Hague, the Moscow Metro.<br />

– Noise control: prevention of noise reverberation, for example in<br />

the Second Heinenoord Tunnel under the Oude Maas river.<br />

– Orientation aids: sightlines, orientation features, for example the<br />

prize-winning underground car park at Arnhem Central Station.<br />

– Physical environmental quality: constant temperature and<br />

humidity, noise insulation, as in the Zeeland Record Office in<br />

Middelburg, the National Archives in Limburg and the<br />

underground houses at the ‘Kleine Aarde’ in Boxtel.<br />

Designs should pay particular attention to (social) safety,<br />

maintenance and management, and the transition between the<br />

surface and the underground environment.<br />

Transitional areas<br />

Design aspects that play an important role in the transition from<br />

surface to below ground are:<br />

– Envelope/interior<br />

– Views, sightlines, legibility<br />

– Daylight, lighting, colours<br />

– Integration in the surroundings, identity

<strong>NovaTerra</strong> <strong>Connected</strong> <strong>Cities</strong> / december 2005 / 19<br />

Some of the best designed transitional areas are underground<br />

stations. For example: Canary Wharf, where the curving signature<br />

glass canopies allow natural light to penetrate deep below ground,<br />

enhanced by functionally designed artificial lighting; the lighting<br />

built into the escalators accentuates sightlines and orientation.<br />

Or the Bilbao metro, where escalators rapidly transport travellers<br />

to street entrances covered by tree-shaped glass canopies. In the<br />

Netherlands, the ‘lid’ above Blaak station both signals the location<br />