aagbi

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

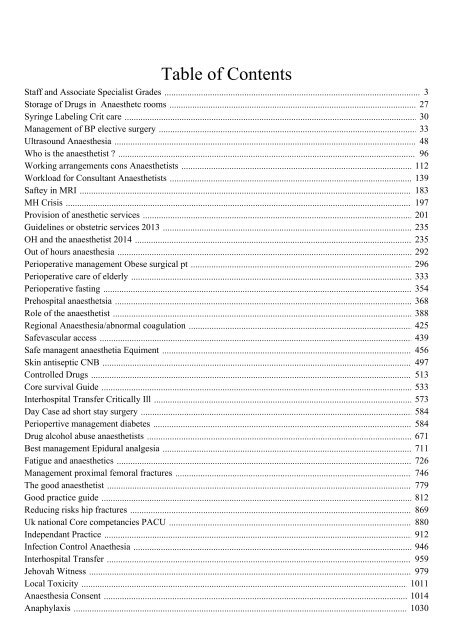

Staff and Associate Specialist Grades<br />

Storage of Drugs in Anaesthetc rooms<br />

Syringe Labeling Crit care<br />

Management of BP elective surgery<br />

Ultrasound Anaesthesia<br />

Who is the anaesthetist ?<br />

Working arrangements cons Anaesthetists<br />

Workload for Consultant Anaesthetists<br />

Saftey in MRI<br />

MH Crisis<br />

Provision of anesthetic services<br />

Guidelines or obstetric services 2013<br />

OH and the anaesthetist 2014<br />

Out of hours anaesthesia<br />

Perioperative management Obese surgical pt<br />

Perioperative care of elderly<br />

Perioperative fasting<br />

Prehospital anaesthetsia<br />

Role of the anaesthetist<br />

Regional Anaesthesia/abnormal coagulation<br />

Safevascular access<br />

Safe managent anaesthetia Equiment<br />

Skin antiseptic CNB<br />

Controlled Drugs<br />

Core survival Guide<br />

Interhospital Transfer Critically Ill<br />

Day Case ad short stay surgery<br />

Periopertive management diabetes<br />

Drug alcohol abuse anaesthetists<br />

Best management Epidural analgesia<br />

Fatigue and anaesthetics<br />

Management proximal femoral fractures<br />

The good anaesthetist<br />

Good practice guide<br />

Reducing risks hip fractures<br />

Uk national Core competancies PACU<br />

Independant Practice<br />

Infection Control Anaethesia<br />

Interhospital Transfer<br />

Jehovah Witness<br />

Local Toxicity<br />

Anaesthesia Consent<br />

Anaphylaxis<br />

Table of Contents<br />

3<br />

27<br />

30<br />

33<br />

48<br />

96<br />

112<br />

139<br />

183<br />

197<br />

201<br />

235<br />

235<br />

292<br />

296<br />

333<br />

354<br />

368<br />

388<br />

425<br />

439<br />

456<br />

497<br />

513<br />

533<br />

573<br />

584<br />

584<br />

671<br />

711<br />

726<br />

746<br />

779<br />

812<br />

869<br />

880<br />

912<br />

946<br />

959<br />

979<br />

1011<br />

1014<br />

1030

Blood components and alternatives<br />

Anaesthesia Team<br />

Anaphylaxis management<br />

Arterial blood sampling and hypoglyceamic brain injury<br />

Asistance for the anaesthetist<br />

Age and the anaesthetist<br />

Safe transfer Brain INjury<br />

Care of critically Ill child<br />

Catastrophes in anaesthesia<br />

Blood transfusion<br />

Checking anaesthetic equipement<br />

Private billing<br />

1032<br />

1090<br />

1112<br />

1155<br />

1169<br />

1185<br />

1204<br />

1228<br />

1244<br />

1276<br />

1299<br />

1319

Staff and Associate<br />

Specialist Grades<br />

2008<br />

Published by<br />

The Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland,<br />

21 Portland Place, London W1B 1PY<br />

Telephone 020 7631 1650 Fax 020 7631 4352<br />

info@<strong>aagbi</strong>.org<br />

www.<strong>aagbi</strong>.org September 2008<br />

1

MEMBERSHIP OF THE WORKING PARTY<br />

Dr Leslie Gemmell<br />

Dr Ramana Alladi<br />

Dr Michael Wee<br />

Dr Kate Bullen<br />

Dr Andy Lim<br />

Dr Anthea Mowat<br />

Chairman, Honorary Secretary Elect, AAGBI<br />

Chairman of SAS Committee and Council Member, AAGBI<br />

Vice President, AAGBI<br />

Deputy Chairman, BMA<br />

Chairman of SAS Committee and Council Member,<br />

Royal College of Anaesthetists<br />

Member, Staff and Associate Specialists Committee, AAGBI<br />

BMA Staff and Associate Specialists Conference Chair<br />

Ex Officio<br />

Dr David Whitaker<br />

Dr Richard Birks<br />

Dr Iain Wilson<br />

Dr William Harrop-Griffiths<br />

Dr Ian Johnston<br />

Dr David Bogod<br />

President<br />

President Elect<br />

Honorary Treasurer<br />

Honorary Secretary<br />

Honorary Membership Secretary<br />

Editor-in-Chief, Anaesthesia<br />

Acknowledgement<br />

The Working Party is grateful to Dr Christine Robison for her advice and comments.<br />

© Copyright of the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland.<br />

No part of this book may be reproduced without the written permission of the AAGBI.<br />

2

CONTENTS<br />

Section 1 Introduction 4<br />

Section 2 Recommendations 5<br />

Section 3 The grades 6-10<br />

Section 4 Model SAS charter 11-12<br />

Section 5 AAGBI and the SAS anaesthetist 13-14<br />

Section 6 The SAS contract 15-18<br />

Section 7 References and useful websites 19<br />

Appendix 1 20<br />

Appendix 2 21<br />

3

1. Introduction<br />

The number of Staff and Associate Specialist (SAS) doctors employed in the National Health Service<br />

has grown rapidly in the last few years, during which there have been changes in government policy<br />

that include the introduction of revised terms and conditions of service for both Staff Grades and<br />

Associate Specialists. The Royal College of Anaesthetists (RCoA) has published advice on appointments<br />

procedures for these grades. The number of SAS doctors has increased further since the restructuring<br />

of medical careers within the Modernising Medical Careers (MMC) process, in particular producing a<br />

marked increase in the appointment of Trust Grade doctors.<br />

The 1990 NHS and Community Care Act allowed the establishment of NHS Foundation Trusts with the<br />

freedom to offer new staff, including doctors other than those in the training grades, contracts under<br />

their own terms and conditions of service. The national ceiling on Staff Grade numbers was formally<br />

removed in 1997, and employing authorities and Trusts were made responsible for individual Staff<br />

Grade appointments.<br />

The Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland (AAGBI) has produced two guideline<br />

documents, the last being published in 1998, offering recommendations and advice to Non-Consultant<br />

Career Grade Doctors (NCCGs). Since then, there have been significant changes to the grades. The<br />

generic name ‘Non-Consultant Career Grade’ (NCCG) has been replaced by ‘Staff and Associate<br />

Specialist’ (SAS) grade. This appears not to include other grades such as Clinical Assistant, Trust Grade<br />

and Hospital Practitioner. However, the Working Party wishes to include all grades considered in<br />

earlier guidance.<br />

The AAGBI established its SAS Committee in 2002 and the RCoA held elections for the first two SAS<br />

council members in the same year.<br />

This edition replaces existing advice contained in the 1992 and 1998 AAGBI publications. The advice is<br />

intended for doctors in the various grades and for Clinical Directors of Departments of Anaesthesia.<br />

4

2. Recommendations<br />

The AAGBI strongly recommends that all appointments are made to the nationally recognised grades<br />

of Staff Grade or Associate Specialist.<br />

The AAGBI does not recommend non-standard grades and other non-training grades with variable<br />

terms and conditions of service.<br />

All grades are clinically responsible to a named consultant and should not be put in the position<br />

of taking ultimate clinical responsibility for the care of patients. There should be an established<br />

mechanism for any eligible Staff Grade doctor to be promoted to the post of Associate Specialist.<br />

Consultants responsible for SAS doctors should ensure that professional support is available. Every<br />

doctor should have a nominated consultant as a mentor.<br />

The AAGBI supports the RCoA in advising that all SAS appointees should have a postgraduate<br />

qualification. The applicant should have undergone suitable training and should have gained sufficient<br />

relevant clinical experience to fulfill the requirements in the job plan.<br />

Suitably experienced SAS doctors who are involved in supervising trainees are encouraged to apply to<br />

be entered in the RCoA’s ‘Approved to Teach’ list, with the support of the College Tutor.<br />

An SAS doctor’s contract should include time for pre-operative and postoperative visits. Provision in<br />

the job plan must be made for activities such as audit, research, appraisal and continuing professional<br />

development (CPD) activities.<br />

The AAGBI recommends a minimum weekly commitment to anaesthesia of three notional half days or<br />

equivalent, including at least two clinical sessions, with adequate time for all supporting professional<br />

activities.<br />

SAS doctors who have job plans involving emergency work must maintain the appropriate skills.<br />

All SAS doctors should have an annual appraisal that should inform job planning.<br />

All SAS doctors should, as a part of their job plan, spend time working with a consultant.<br />

Provision for adequate study and professional leave must be made to all SAS doctors. Funding must<br />

be available for these activities.<br />

All SAS doctors should have representation at departmental level and be allowed to attend departmental<br />

and directorate meetings. There should be representation on the Local Negotiating Committee at Trust/<br />

Board level, and they should be included in the Trust/Board negotiations.<br />

5

3. The grades<br />

Associate Specialist [1-6]<br />

The Associate Specialist grade was introduced in 1981; it was a development of the Medical Assistant<br />

grade. It is a permanent career grade of limited clinical responsibility. Since 1991 an inclusive<br />

professional contract, similar to that of the pre-2003 NHS Consultant Contract, has been in place, with<br />

discretionary points replacing the performance supplement in 1996. Associate Specialists are employed<br />

on contracts based on 11 notional half days per week, in which one notional half day is equivalent<br />

to a minimum of 3.5 hours worked flexibly. Associate Specialists are senior hospital doctors who are<br />

clinically responsible to a named consultant and who should not therefore be put in the position of<br />

taking ultimate responsibility for care of patients. Associate Specialists are subject to the European<br />

Working Time Directive (WTD), which limits time worked to a maximum of 48 hours per week on<br />

average. Associate Specialists are senior hospital doctors and should therefore occupy a senior position<br />

on the on-call rota.<br />

A medical practitioner appointed to the Associate Specialist grade should have served a minimum of four<br />

years in a Specialist Registrar post or Staff Grade post, at least two of which have been in the appropriate<br />

specialty. Equivalent service is acceptable with the agreement of the relevant College Regional Adviser<br />

and Regional Postgraduate Dean. The doctor should have completed 10 years’ medical work, either as<br />

a continuous period or in aggregate, that is acceptable by the General Medical Council (GMC) for full,<br />

limited or temporary - but not provisional - registration. Possession of a higher qualification, e.g. the<br />

FRCA, is desirable but not mandatory.<br />

Associate Specialist posts are often personal appointments established for those doctors committed<br />

to a career in the hospital service who are unable to complete higher professional training or who,<br />

on completion of higher professional training, are unable or do not wish to accept the full clinical<br />

responsibility of a consultant appointment.<br />

In certain circumstances in England and Wales, Trusts may advertise for and recruit Associate Specialists<br />

directly. However, an Associate Specialist post should only be established when it is in the best interests<br />

of the service. A job description for the post should be drawn up with the advice of a representative of<br />

the RCoA. The Central Consultants and Specialists Committee (CCSC) of the British Medical Association<br />

(BMA) has produced a model workload document for Associate Specialists, which was endorsed by<br />

the newly formed Staff and Associate Specialists Committee of the BMA. Associate Specialists have the<br />

option of whole time, maximum part-time or part-time contracts and, although they have the right to<br />

undertake private practice, they may encounter difficulties when claiming reimbursement from private<br />

health care providers.<br />

When job planning, it is worth noting paragraph 26 of the current Terms and Conditions: National Health<br />

Service Hospital Medical and Dental Staff and Doctors in Public Health Medicine and the Community<br />

Health Service (England and Wales), Terms and Conditions of Service September 2002 Version 2 – 1<br />

December 2002, Version 3 – 10 January 2003, Version 4 – 6 February 2004, Version 5 – 17 February<br />

2005, Version 6 – 1 June 2005, Version 7 – 1 March 2007, and Version 8 – 30 July 2007.<br />

6

Associate Specialists should ensure that their workload, including on-call, is reviewed annually.<br />

Consideration should be given not only to the frequency of on-call but also to the intensity of the work.<br />

Particular care should be taken to ensure that the problems previously encountered by trainees are not<br />

merely transferred to the SAS grades.<br />

In any consideration of a career grade appointment, the following factors should be taken into account:<br />

• The need to develop a consultant-based service<br />

• Overall consultant responsibility for patient care<br />

• Consultant cover both in and out of hours in anaesthesia and, where necessary,<br />

in related subspecialties;<br />

• Provision for the teaching of junior doctors and the supervision of both junior<br />

and career grade medical staff<br />

The appointment committee for new Associate Specialist appointments normally comprises, as a<br />

minimum:<br />

• A senior manager<br />

• A consultant from the Trust/Board in the relevant specialty<br />

• An external senior hospital doctor nominated by the RCoA<br />

Guidance for personal regrading from Staff Grade to Associate Specialist is available on the BMA<br />

website: http://www.bma.org.uk/ap.nsf/content/home<br />

Staff Grade [7,8]<br />

The Staff Grade was introduced in 1988 to meet service requirements, and a national ceiling on<br />

numbers that limited the number of Staff Grades to 10% of the total number of consultants was<br />

removed in 1997 when the current Staff Grade contract was introduced (except in Scotland). A<br />

significant number remain on the pre-1997 contract. Whilst Staff Grade doctors are regarded as senior<br />

hospital doctors, it is important to remember that they are in a non-training career grade. As such, they<br />

exercise an intermediate level of clinical responsibility as delegated by the consultant to whom they<br />

are responsible.<br />

A full time Staff Grade contract is for 10 sessions, all of which are superannuable. Staff Grade doctors<br />

are paid at the same sessional rate for work done during working hours or out-of-hours. A session<br />

is four hours, and WTD regulations limit work to an average of 48 hours per week. The duration of<br />

sessions outside normal working hours may vary subject to local Trust negotiation.<br />

It is recommended that doctors (including those in non-standard posts) transfer to the new terms of<br />

service unless it is clearly disadvantageous to do so. Non-standard contracts do not afford the same<br />

protection as nationally agreed terms of service. The BMA has established LNCs in Trusts and Health<br />

Boards to represent doctors of all grades.<br />

7

When drawing up job descriptions for a Staff Grade, employing authorities have complete flexibility,<br />

after consultation with the responsible consultant, with regard to the deployment, location and<br />

rostering of the available sessions. Currently, the RCoA recommends that those SAS doctors without<br />

a postgraduate qualification should not work in isolated areas unsupervised.<br />

A Staff Grade is normally accountable to a named consultant, normally the Clinical Director but,<br />

on a day-to-day basis, to the duty consultant. A model job description is available from the BMA.<br />

The formal requirements for entry to the Staff Grade are:<br />

• full registration with the GMC<br />

• either a minimum of three years’ full time hospital service at Senior House<br />

Officer (SHO) or higher grade, including adequate experience in the relevant specialty;<br />

or equivalent experience<br />

This requirement may be waived if, in the opinion of the College assessor, the applicant has undertaken<br />

suitable training and has gained sufficient relevant experience to fulfil the requirements of the<br />

job plan.<br />

It is recommended that the job plan be approved by the RCoA Regional Education Advisor before the<br />

post is advertised.<br />

The Advisory Appointments Committee in England normally comprises, as a minimum, the following<br />

people:<br />

• A lay Chairman appointed by the Trust/Board<br />

• A consultant anaesthetist from outside the Trust/Board, approved by the Royal College<br />

• A consultant anaesthetist (usually the Clinical Director) from the Trust/Board<br />

The composition of the panel may be different in the devolved nations. After ratification of the<br />

appointment by the Trust, there is normally a probationary period of one year at the end of which<br />

time, subject to approval, the post becomes permanent and subject to standard terms of notice. The<br />

AAGBI strongly disapproves of annually renewable contracts. All Staff Grades should ensure that their<br />

workload, including on-call commitments, is reviewed annually. Consideration should be given not<br />

only to the frequency of on-call but also to the intensity of that work.<br />

Guidance for personal regrading from Staff Grade to Associate Specialist is available on the BMA<br />

website.<br />

Hospital Practitioner [9]<br />

A doctor appointed to this grade has to be a principal in general practice and must have been fully<br />

registered for at least four years. The numbers in this grade are diminishing, probably as a result of<br />

clinical governance considerations, the difficulties of appraisal in dual specialties, the increasing<br />

workload of General Practitioners and the decrease in the number of anaesthetists who have undergone<br />

a substantial period of training before entering general practice.<br />

8

Appointment is limited to those principals who have at least two years’ whole-time (or equivalent parttime)<br />

experience in anaesthesia. Although a postgraduate qualification is not a specific requirement for<br />

the grade, the AAGBI supports the RCoA recommendation that possession of an FRCA or equivalent<br />

is desirable.<br />

Appointment is renewable after one year, subject to confirmation, until the incumbent reaches<br />

retirement age or ceases to be a principal in general practice. This grade is responsible to a named<br />

consultant, and the AAGBI recommends a minimum of two clinical sessions with appropriate time for<br />

pre-operative visits and postoperative care, i.e. three notional half days per week.<br />

Thirty days’ study leave within each three-year period should be included in the contract, and hospital<br />

practitioners would normally be expected to participate in clinical audit and departmental meetings.<br />

Departments of Anaesthesia and College Tutors must encourage Trusts to support applications from<br />

this grade to participate in CPD.<br />

Clinical Assistants (part-time medical officers) [10]<br />

The AAGBI strongly recommends that no further Clinical Assistant appointments be made and that Staff<br />

Grade posts with nationally agreed terms and conditions of service be created in the future when the<br />

need arises. When General Practitioners wish to continue clinical sessions, the Hospital Practitioner<br />

grade would be a more appropriate appointment. It is essential that College Tutors, postgraduate deans<br />

and Trust managers support the need for CPD by clinical assistants, both for the benefit of the individual<br />

and as an intrinsic requirement of good practice, clinical governance and risk management.<br />

Non-standard grades<br />

Many Trusts have created new grades of doctors with non-standard terms and conditions of service to<br />

circumvent manpower planning mechanisms controlling the proportion of SAS doctors within trusts<br />

and also as a result of resource pressures. Such irregular posts are not protected by national terms and<br />

conditions of service, and the BMA has campaigned for many years against their creation. The AAGBI<br />

supports this view.<br />

These non-standard appointments have a number of titles, including Trust Grade doctor, Trust Specialist,<br />

Staff Specialist, Clinical Fellow and Clinical Specialist. The contracts usually incorporate out-of-hours<br />

work at a rate of remuneration defined by the Trust and often permit the use of fixed-term contracts.<br />

The revised terms and conditions of service for Staff Grades and the ability to appoint Associate<br />

Specialists directly have made such posts unnecessary. The AAGBI strongly recommends that<br />

employers use this opportunity to offer existing non-standard grade doctors of the appropriate level<br />

the option to transfer to the new terms and conditions of service. Those doctors who fail to meet the<br />

standards set down in this advice should be offered the opportunity to undergo further training. If, in<br />

exceptional circumstances, a Trust or Department of Anaesthesia deems such a non-standard post to<br />

be necessary, it is recommended that potential applicants obtain advice from the BMA, the AAGBI or<br />

the College tutor.<br />

9

4. Model SAS Charter<br />

The NHS employer should aim to provide a working environment that recognises both the diversity of<br />

SAS doctors and the major contribution that they make to patient care. The NHS employer should realise<br />

that the SAS doctors need both support and resources to develop personally and professionally. The<br />

NHS employer should be committed to ensuring that the role of the SAS doctor is fully acknowledged<br />

and respected by management, colleagues and patients. In order to deliver these aspirations, the<br />

following recommendations are made.<br />

Each Trust should work towards every SAS doctor having the following:<br />

• An appropriate contract of employment incorporating national terms and conditions<br />

• An appropriate agreed job plan. This may only be changed by mutual agreement<br />

between the SAS doctor and the Clinical Director/Lead in accordance with agreed local<br />

procedures for appraisal and job plan review<br />

• An adequate daytime session allocation with separate and identifiable time allocated<br />

for administration, education, audit and teaching commitments, etc. This should not<br />

be any less favourable than the time allotted to consultants undertaking similar<br />

clinical duties<br />

• Access to office accommodation and a computer in each directorate in which<br />

SAS doctors are employed. This should include access to email and suitable storage<br />

facilities for confidential work, related papers, books, etc<br />

• Adequate support and time allocation to allow SAS doctors to participate fully<br />

in the employer’s appraisal process, including access to appraisal training and the<br />

necessary CPD and study leave requirements, which are a natural consequence<br />

of appraisal<br />

• Adequate and fully funded study leave<br />

• All permanent SAS doctors should be members of the Medical Staff Committee/Hospital<br />

Medical Board and should be invited to attend meetings<br />

• There should be SAS representation on the LNC<br />

• The employer should agree a mechanism or adopt BMA recommendations for regrading<br />

from Staff Grade to Associate Specialist<br />

• Access to a fair and appropriate mechanism for the award of optional points for<br />

Staff Grades and discretionary points for Associate Specialists. The BMA recommend<br />

a minimum number of discretionary points/optional points (available at a rate of 0.35<br />

points per year per eligible candidate) that should be awarded. The points should be<br />

awarded for work and contributions over and above that normally expected for a doctor<br />

in the SAS grade. Guidance on completion of the application form is available on the<br />

BMA website<br />

• SAS doctors should have equal access to the benefits of the Improving Working Lives<br />

initiative [12]<br />

• All SAS doctors should be members of the directorate and should be invited to attend<br />

directorate and departmental meetings<br />

10

5. The AAGBI and the SAS anaesthetist<br />

The SAS Committee (SASC) of AAGBI<br />

The AAGBI SASC was established in 2002. The remit of the committee is to:<br />

• Represent the interests of SAS members of the AAGBI<br />

• Advise the AAGBI Council on matters relating to SAS doctors<br />

• Promote the aims and benefits of the AAGBI to SAS doctors<br />

• Encourage the professional development of SAS doctors<br />

• Ensure effective collaboration with the SAS committee of the RCoA,<br />

other Royal Colleges and professional bodies<br />

The Committee is structured as follows:<br />

• Members of the Executive of the AAGBI<br />

• Elected members of the Council as nominated by Council<br />

• A representative of RCoA SAS Committee<br />

• Five SAS representatives co-opted by the Council on the recommendation<br />

of the SAS committee<br />

SAS doctors and teaching<br />

The College, supported by the AAGBI, recognises that SAS anaesthetists have a valuable role to play in<br />

teaching. To be a teacher, possession of an FRCA is not a prerequisite but, like consultants, SAS doctors<br />

must fulfill the RCoA’s CPD requirements. This is essential for those clinical areas in which they have<br />

clinical and on-call responsibilities.<br />

The RCoA encourages College Tutors to identify those SAS anaesthetists with aptitude and to<br />

nominate them to the local School of Anaesthesia, specifying the areas in which they have appropriate<br />

expertise.<br />

SAS doctors who are Fellows or Members of the RCoA and who have been accepted by their School<br />

of Anaesthesia as teachers may, if they wish, ask for their name to be recorded with the College as<br />

‘Approved to Teach’. This list is available on the RCoA website [13].<br />

The specific areas in which SAS doctors teach are best identified at local level, but may include<br />

specialist operating lists in which an individual has expertise.<br />

SAS anaesthetists who teach trainees must have the opportunity to acquire the skills of a competent<br />

teacher.<br />

When being taught by a SAS doctor, trainees must at all times have unimpeded access to consultants<br />

for advice.<br />

11

6. The SAS contract<br />

What is the contract?<br />

A contract is a set of statements governing the agreement between you and your employer. It covers<br />

what work you agree to perform, what facilities your employer agrees to make available for you to<br />

do this work, and what your employer agrees to reward you for your work. It must be both fair and<br />

compatible with the law. Associate Specialists have the option of a whole-time or maximum part-time<br />

contract or may be employed on a part-time basis.<br />

The contract is not a single document. It has several components:<br />

• The statement of particulars (called the contract)<br />

• The terms and conditions of service<br />

• The job plan<br />

The contract<br />

This is usually a document that states your job title, your employing organisation, further details and is<br />

signed by both you and your employer. Standard contracts are negotiated nationally and should not be<br />

varied locally, except when individual circumstances demand changes that are mutually agreed.<br />

The terms and conditions of service<br />

This is a set of rules describing in more detail how the contract operates. The rules are congruent with<br />

the statement of particulars. Employers do not usually circulate these except on request but they can<br />

be found on the web. They are negotiated nationally and should not be varied locally except where<br />

a collective agreement has been reached with the LNC for medical and dental staff in your Trust.<br />

Examples of such agreements might be to vary the provisions of additional programmed activities in<br />

the case of significant private practice, to confirm arrangements for fee-paying services or to agree<br />

appropriate places for supporting professional activities.<br />

The job plan<br />

This is your personal and detailed agreement about your work. The job plan is congruent with the terms<br />

and conditions of service. It will describe the purpose of your job, your work timetable, your objectives<br />

and the supporting resources that should be allocated to help you achieve them. It should include any<br />

other personal agreements about the way you work.<br />

Job plan annual review<br />

The job plan of every SAS doctor (including the work programme) should be subject to an annual<br />

review. This annual review should provide an opportunity for the SAS doctor and the named consultant<br />

to discuss any problems that may have arisen in the preceding year and to agree any changes that need<br />

to be made to meet new circumstances or changed service priorities. It is likely that, in many cases, job<br />

plans will need to be amended only occasionally and even then will be subject to minimal alteration.<br />

12

Where the SAS doctor and the named consultant are unable to reach agreement on the content of<br />

the job plan, either initially or at an annual review, local procedures that provide for the resolution of<br />

grievances or differences relating to an individual practitioner’s duties should be followed.<br />

Preparing for a job plan meeting: keeping a diary and collecting data<br />

It is crucial in preparing for the job planning meeting that you have accurate information about the<br />

job you currently do. This is particularly important if you are going to argue that your work justifies a<br />

revision of the plan. There is no real alternative to collecting this data via a diary of your activity.<br />

For the most part, your work is likely to follow a regular pattern from week to week and should be<br />

relatively easy to assess. There will undoubtedly be exceptions for SAS doctors who do not have such<br />

a regular pattern and, in those circumstances, a more detailed assessment will be necessary. The<br />

assessment will then need to be made over a longer period. Note in particular that your workload is<br />

likely to be higher when you have colleagues on annual leave. Think about this when you complete<br />

your diary.<br />

For many SAS doctors, the most difficult task will be to assess the amount of time spent doing actual<br />

work whilst on-call because this may well vary from night to night or there may be a concerted period<br />

of on-call, for instance during one week in five. There may therefore need to be an assessment of on-call<br />

work over a longer period.<br />

Include in the diary all the work you do, from when you arrive at work each day until the time you<br />

leave. Travelling time is included between sites and where extra time is taken to get to a site different<br />

to your normal one. All work you do when on-call should also be included, such as telephone advice,<br />

travelling to and from work and waiting to begin work. SAS doctors, like most other professionals,<br />

would expect to be contactable during their lunch breaks and to take such breaks flexibly. Where this<br />

happens, it is reasonable to count such breaks as part of working time.<br />

Fixed commitments<br />

For the SAS doctor on a whole-time (or maximum part-time for an Associate Specialist) contract,<br />

between five and seven notional half-days, depending on specialty, should normally be allocated as<br />

fixed commitments in the work programme. For Associate Specialists on other part-time contracts, at<br />

least half of the notional half-days should normally be allocated to fixed commitments. The number<br />

of fixed commitments may be varied with the agreement of the Associate Specialist and their Clinical<br />

Director/Lead. A fixed commitment, e.g. an out-patient clinic or operating list, is a commitment that an<br />

Associate Specialist must fulfill, except by agreement with their named consultant or in an emergency.<br />

Examples of job plans are given in Appendix 1<br />

Waiting List Initiative lists: SAS doctors should be allowed, with the agreement of the department, to<br />

undertake waiting list initiative lists provided appropriate consultant cover is made available.<br />

13

Work diaries should take note of all aspects of work done. This will comprise:-<br />

• Direct clinical care of patients, including all patient-related administration such<br />

as telephone calls, letters, reviewing results, etc.<br />

• Activities to support professional development and CME including audit, training,<br />

research and other similar non-clinical activities<br />

• Agreed additional NHS responsibilities and agreed external duties<br />

Working time is divided into four components:<br />

1. Direct Clinical Care (DCC)<br />

2. Supporting Professional activities (SPA)<br />

3. Additional NHS responsibilities<br />

4. External duties<br />

Examples of DCCs, SPAs, additional NHS responsibilities and external duties can be<br />

found in the AAGBI document giving guidance for the new consultant contract [14] There are example<br />

job plans given in Appendix 1.<br />

Study leave/audit<br />

There should be opportunities for further training and participation in regular CPD in line with the<br />

recommendations of the RCoA.<br />

Appropriate funding and paid time off must be made available by the trust in accordance with national<br />

agreements.<br />

All SAS doctors should take part in regular departmental and hospital-wide audit/clinical governance<br />

and it is recommended that this is formally included in the job plan.<br />

Named consultant<br />

Since the inception of the NHS, it has been a requirement that every patient’s care is undertaken<br />

either by a consultant or by a trainee or SAS doctor under the supervision of a named consultant. All<br />

departments should have an agreed and recognised system in which a ‘named’ consultant is identified<br />

and recorded for every patient. This will be the person to whom SAS doctor should turn to for advice<br />

or help with a case. It should be clear to the SAS doctor how the local system operates and named<br />

individuals should be able to provide or arrange for immediate advice or direct assistance as required.<br />

The exact local implementation of supervision arrangements for individual SAS doctor will depend<br />

upon a number of factors, not the least of which will be the knowledge, skills and experience of the<br />

individual. Clearly, when a senior Associate Specialist is working in an area with which he or she is<br />

very familiar, the requirement for contact and discussion about individual cases will be uncommon.<br />

In contrast, it may be appropriate for a recently appointed Staff Grade doctor to be more closely<br />

supervised. For further details, please refer to the AAGBI SAS Handbook.<br />

14

Discretionary points and optional points<br />

Performance supplements for Associate Specialists introduced in 1991 have been replaced by<br />

Discretionary Points. Associate Specialists and Staff Grades on the maximum salary scale are eligible for<br />

the award of points: discretionary points for Associate Specialists and optional points for staff grades.<br />

These are consolidated payments made in addition to the maximum salary scale at the discretion of<br />

the employer. They are not seniority payments, nor are they automatic annual increments. They are<br />

superannuable.<br />

The award of points is for work and contributions over and above that normally expected of a doctor<br />

of that grade. Key criteria are clinical expertise and service to patients but account should be taken of<br />

overall workload and its intensity.<br />

It is important that Trusts/Boards set up local award panels in accordance with national guidelines and<br />

that they encourage SAS doctors to apply for these awards. All SAS doctors who are eligible to apply<br />

should make a personal submission each year. The consultants responsible for the work of SAS doctors<br />

may be required to give written recommendations.<br />

There are no absolute requirements to Trusts/Boards to award such discretionary/optional points, but<br />

the BMA recommendation is that a total of 0.35 points be awarded per eligible Associate Specialist per<br />

year and 0.35 points per eligible Staff Grade per year.<br />

15

7. References<br />

1. HSG (91)18: The associate specialist grade: terms and conditions of services. November 1991.<br />

2. DHSS PM (81) 16 recommended form of contract for associate specialists. 1981.<br />

3. NHS Management Executive guidelines relating to terms and conditions of service for doctors in<br />

the associate specialist grade HSG (91) 18. November 1991.<br />

4. Delegation of procedures for appointment to the associate specialist in medical specialties as<br />

announced by the Executive EL (91) 150. November 1991.<br />

5. Arrangements for the payment of Discretionary points to associate specialists AL (MD) 7/95.<br />

1995.<br />

6. NHS executive document on working draft to develop a quality framework for HCHS medical<br />

and dental staffing Annex 2 EL (97) 25. 1995.<br />

7. Advance Letter (MD) 4/97: Terms and Conditions of Service for the Staff Grade. NHS Executive<br />

July 1997.<br />

8. Staff grade DHSS circular giving guidance on arrangements for the employment of hospital<br />

medical and dental staff on the then new staff grade HC (88) 58 and annexes. 1998.<br />

9. In 1979 the Department of Health and Social Security issued guidelines setting out<br />

arrangements for the employment of hospital practitioners HC 7916. The NHS Executive issued<br />

summary guidance amending these arrangements HSG (93) 50. 1993.<br />

10. Guidance relating to conditions of service for clinical assistants was issued by the Department<br />

of Health and Social Security DA (86) 11. 1986.<br />

11. Advance Letter (MD) 05/02 regarding appraisal for NCCGs.<br />

12. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Managingyourorganisation/Humanresourcesandtraining/<br />

Modelemployer/Improvingworkinglives/index.htm<br />

13. http://www.rcoa.ac.uk/docs/SAS-teach.pdf<br />

14. http://www.<strong>aagbi</strong>.org/publications/guidelines/docs/jobplanning05.pdf<br />

16

Useful websites<br />

The Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland www.<strong>aagbi</strong>.org<br />

The Royal College of Anaesthetists www.rcoa.ac.uk<br />

British Medical Association (SAS Contract) www.bma.org.uk/sascontract<br />

Department of Health www.dh.gov.uk<br />

General Medical Council www.gmc-uk.org<br />

NHS www.nhs.uk<br />

Sick Doctors Trust www.sick-doctors-trust.co.uk<br />

17

APPENDIX 1<br />

Job plans<br />

Example of an 11 notional half day Associate Specialist job plan with out of hours emergency cover.<br />

5 clinical sessions, 3 of which are fixed (1 being special interest list)<br />

2 for pre-operative and postoperative visits<br />

1 for CPD/Audit<br />

2 for out of hours cover (1 night per week; and 1 in 5 full weekends or 2 in 5 split weekends)<br />

1 NHD with no clinical work<br />

Example of 12 session Staff Grade post with out of hours cover<br />

3 clinical theatre sessions (one of which is always accompanied)<br />

2 clinical emergency sessions (often ITU cover)<br />

1 session to attend teaching programme (1 week in 3, other week doing emergency cover)<br />

1 session for pre-operative and postoperative visits<br />

1 session for CPD/Audit admin<br />

4 sessions for one night per week of out of hours cover<br />

Example of 10 session Staff Grade post with no out of hours emergency cover and additional<br />

management duties<br />

6 clinical theatre sessions (1 of which is accompanied)<br />

2 sessions for pre-operative and postoperative visits<br />

1 session for CPD/audit<br />

1 session for admin duties (departmental rota/leave co-ordination)<br />

Example of an 11 notional half day Associate Specialist job plan with no out of hours emergency<br />

cover, but with special interest, e.g. chronic pain work<br />

4 clinical theatre sessions<br />

2.5 sessions for chronic pain team (2 clinical and 1 administration)<br />

1 session for admin duties (departmental leave/rota co-ordination)<br />

1 session for CPD/ audit<br />

1.5 sessions for pre-operative and postoperative visits<br />

Example of a 6 session/notional half day (part time) contract<br />

4 clinical theatre sessions<br />

1 session for CPD/Audit/Administration<br />

1 session for pre-operative and postoperative visits<br />

18

APPENDIX 2<br />

Update on the new SAS grade contract<br />

Negotiations on a new national (UK-wide) contract for SAS doctors and dentists began in May 2005.<br />

An agreement was reached with NHS Employers in 2006. The contract was ratified, with some<br />

amendments, by the Government in December 2007, following which SAS grades were balloted, and<br />

voted to accept the contract.<br />

Specialty Doctor<br />

The new contract is offered on an optional basis from 1 April 2008 to doctors / dentists currently in the<br />

following grades:<br />

• Staff Grades<br />

• Associate Specialists<br />

• Senior Clinical Medical Officers<br />

• Clinical Medical Officers<br />

• Non-GP Clinical Assistants<br />

• Non-GP Hospital Practitioners<br />

The new grade of Specialty Doctor will replace the Staff Grade and will be offered by employers from<br />

1 April 2008, so there will be no new appointments to the above grades after that date.<br />

Associate Specialist grade closure<br />

The old Associate Specialist (AS) grade will be closed with effect from 1 April 2008. There is a new<br />

Associate Specialist grade with similar structure to the Specialty Doctor. Current Associate Specialists<br />

will have the option to express an interest in switching to this new Associate Specialist grade. As no<br />

new appointments will be made to Associate Specialist level, the only other route to enter the grade<br />

will be to regrade from eligible Staff Grades, Specialty Doctors or Clinical Assistants, but applications<br />

will only be possible until 31 March 2009, and after that time new applications for regrading will not<br />

be accepted. This will mean that, from 1 April 2009, both the old and new Associate Specialist grades<br />

are closed.<br />

New contract is optional for current SAS grades<br />

Work has begun on implementation and employers will write to all current SAS doctors asking for<br />

expressions of interest in switching to the contract. SAS grades will have 12 weeks from receipt of<br />

the letter from employers to express an interest in the new contract. This does not commit doctors to<br />

accepting the new contract but guarantees back pay to 1 April 2008 once a job plan has been agreed.<br />

Written offers of an agreed job plan need to be accepted within 21 days (28 days in Scotland).<br />

• Current SAS doctors must consider whether they would like to apply for the new contract.<br />

Consideration of individual circumstances will be essential.<br />

• If expressing an interest, it is advisable to begin a diary planning exercise to inform<br />

job planning discussions. This should last for a minimum of six weeks, or one rota cycle,<br />

though a longer period of time would be helpful.<br />

19

• Staff Grades eligible to apply to regrade to the Associate Specialist grade should do so<br />

as soon as possible, as applications will not be accepted after 31 March 2009<br />

• Regrading applications started before 1 April 2008 will be to the old Associate Specialist<br />

contract, with the option then of moving to the new Association Specialist contract.<br />

• Successful applications started on or after 1 April 2008 will be direct to the new Associate<br />

Specialist contract.<br />

• Should it not prove possible to agree a job plan, there is a mediation procedure available.<br />

• If mediation fails, there is an appeals process.<br />

• The BMA SASC is producing further guidance to assist in assimilation.<br />

Programmed Activities (PA)<br />

The new contract for both new Associate Specialist and Specialty Doctor grades are time based, with<br />

each unit of time being a four-hour Programmed Activity (PA). Before signing the contract, you should<br />

have an agreed job plan. The minimum unit of time used in job planning should be 0.5 PA. The contract<br />

for current SAS grades moving to the new contract should be based on a robust diary exercise. Contracts<br />

can be for up to 12 PAs but PAs over 10 are not obligatory, and may not be permanent. Up to 10 PAs<br />

are superannuable.<br />

A full time contract is one with 10 PAs, most of the work being Direct Clinical Care (DCC) with a<br />

minimum of one PA for Supporting Professional Activities (SPA). SAS doctors who currently have more<br />

than one notional half day or session for SPA-type activity should continue to receive this. The minimum<br />

of 1 PA is absolute, and will also apply to part-time staff, i.e. it is not pro-rata. Some SAS grades may<br />

also be eligible to have additional PAs for additional NHS responsibilities or for external duties.<br />

Direct Clinical Care<br />

This is any work to do with care of individual patients, such as:<br />

• Emergency duties: including emergency work carried out during or arising from on-call<br />

(including phone call advice)<br />

• Operating sessions: including pre-and post-operative care<br />

• Ward rounds<br />

• Outpatient clinics<br />

• Clinical diagnostic work<br />

• Other patient treatment, e.g. intensive care work<br />

• Public health duties<br />

• Multi-disciplinary meetings about direct patient care<br />

• Administration related to patient care, e.g. referrals, notes, dictation, correspondence<br />

• Travel: to and from home for on-call work; and between hospitals for elective work<br />

Other areas to be considered are starting work earlier, planning operating list including scheduling<br />

order, prioritising difficult cases, mortality and morbidity meetings if presenting specific patients,<br />

handling complaints.<br />

20

Supporting Professional Activities<br />

There should be a minimum of one SPA in the job plan, though as the SAS doctor becomes more senior<br />

and experienced, it is likely that this will need to be increased, as evidenced by work diary<br />

• Training, e.g. teaching trainees, medical students, paramedical staff or ancillary staff<br />

• Teaching: lectures or seminars whether local, regional or national<br />

• Continuing Professional Development: all activity such as attending professional meetings,<br />

departmental CPD sessions and reading journals<br />

• Audit<br />

• Job planning<br />

• Appraisal<br />

• Research<br />

• Clinical management, including rota co-ordination<br />

• Local clinical governance activity<br />

• Local representational activities<br />

Additional NHS responsibilities<br />

There may be activities that cannot be covered within the time set, which should be recognised as<br />

additional NHS responsibilities. It may be appropriate to replace some DDC PAs to enable this work to<br />

be carried out. Examples include<br />

• Audit lead<br />

• Clinical Governance lead<br />

• Subspecialty or project lead<br />

• Clinical management: Clinical Director, other official Trust management role including<br />

LNC, rota management or Lead Clinician<br />

External duties<br />

This involves activities which are for the greater good of the NHS. The Department of Health recognises<br />

the value of, and has given support for, such activities. If these duties are regular, allowance for them<br />

should be given within the job plan.<br />

Examples include:<br />

• Work for General Medical Council or other national bodies<br />

• College tutor<br />

• NHS disciplinary procedures<br />

• Regional Advisor, deputy, Programme Director<br />

• Trade Union duties, e.g. BMA<br />

• Royal College, Specialist Associations, e.g. AAGBI, Specialist Society work<br />

• University roles<br />

• Work for other NHS bodies, e.g. Healthcare Commission<br />

• Acting as an external member of appointment panels<br />

21

On call supplement<br />

There is a supplement for on-call work, payable as a percentage of the basic salary with the percentage<br />

being dependent on the frequency of the on-call. This will not be payable for a shift pattern. It is payable<br />

for on-call work irrespective of the intensity of the duty.<br />

The supplement is 6% of basic salary for rotas with an on-call frequency equal to or more frequent than<br />

1 in 4, 4% for rotas with frequency less than 1 in 4 or equal to 1 in 8, and 2% for rotas with a frequency<br />

of less than 1 in 8.<br />

This payment is added to basic salary and is superannuable.<br />

Out of Hours work (OOH)<br />

Work actually carried out as Out of Hours work (OOH), as demonstrated by diary exercise, will be<br />

payable at an enhanced rate whereby the rate of pay will be time and a third for a four-hour block of<br />

time actually worked. Alternatively, SAS grades may prefer to consider an OOH PA as a three-hour<br />

block of time of time actually worked, payable as a four-hour PA. OOH work is work done between<br />

19:00 and 07:00 on weeknights and all work at weekends and on public holidays. Where OOH work<br />

is included within the 10-session job plan this will be superannuable. If it forms part of additional PAs<br />

above the basic 10 PAs it will not be superannuable.<br />

Regular OOH worked should be part of the job plan, whether elective or emergency. If the actual<br />

number of OOH hours worked is variable, it can be averaged on a weekly basis for the purposes of job<br />

planning, by using the diary exercise to look at total number of OOH hours actually worked during the<br />

diary period, and dividing by the number of weeks for which the diary was kept. Thus it can then be<br />

designated as a specific amount of DCC time.<br />

It is possible for job plans to include regular elective work to be done in OOH time for specialty doctors,<br />

but this does not apply to associate specialists.<br />

Optional and discretionary points<br />

These awards will no longer exist in the new contract, but will continue to be available for those SAS<br />

doctors who choose to remain in their old contracts.<br />

BMA members can access assistance from the BMA for job planning, for mediation and for appeals.<br />

22

23

21 Portland Place, London W1B 1PY<br />

Tel: 020 7631 1650<br />

Fax: 020 7631 4352<br />

Email: info@<strong>aagbi</strong>.org<br />

www.<strong>aagbi</strong>.org

Storage of Drugs in<br />

Anaesthetic Rooms<br />

Guidance on best practice from<br />

the RCoA and AAGBI

Storage of Drugs in Anaesthetic<br />

Rooms<br />

1<br />

Guidance on best practice from the RCoA and AAGBI<br />

The Royal College of Anaesthetists (RCoA) and Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland (AAGBI) recognise<br />

that secure drug storage makes an important contribution to patient safety, and the safety of the public, but patient safety must<br />

always be the priority. The RCoA and AAGBI support a system of standard operating procedures (SOPs) that makes patient safety<br />

paramount, and recognises that even short delays in accessing drugs may result in an adverse patient outcome. All drugs and<br />

medicines § need to be stored safely. The Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) recognises that there are special requirements for<br />

the storage of drugs in operating theatre departments, and recommends that there should be a system of Standard Operating<br />

Procedures (SOPs) covering each of the activities concerned with medicines use to ensure the safety and security of medicines<br />

stored and used in operating departments. 1<br />

A particular situation not mentioned in the RPS document is that anaesthetic rooms, which function as a form of ‘annexe’ to the<br />

main operating theatre, are usually a place in which drugs and fluids are stored. During the conduct of an anaesthetic and surgery<br />

the anaesthetic room may temporarily and intermittently be unoccupied when the patient is in theatre. Care Quality Commission<br />

(CQC) inspectors have in recent months identified a need for guidance as to whether the storage of drugs and fluids in unlocked<br />

cupboards in temporarily unoccupied anaesthetic rooms is acceptable.<br />

The Health and Social Care Act 2008 2 demands that patients and healthcare staff be protected ‘against the risks associated with<br />

the unsafe use and management of medicines by means of the making of appropriate arrangements for the obtaining, recording,<br />

handling, using, safe keeping, dispensing, safe administration and disposal of medicines’.<br />

There is clear guidance on the storage of Controlled Drugs such as morphine, cocaine, and fentanyl in this setting, 3 but there is<br />

currently no specific advice on best practice for the storage of non-controlled drugs and fluids in anaesthetic rooms. The Royal<br />

College of Anaesthetists (RCoA) and the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland (AAGBI) convened a working<br />

party to address this issue. This document is the report of the working party.<br />

Guidance<br />

1 Patient safety must be the paramount consideration. Immediate access to a variety of drugs can sometimes be essential, such<br />

that even short delays in drug availability can make a difference to patient outcome.<br />

2 It is not possible to provide a definitive list of ‘emergency drugs’ that should be immediately available at all times, as these<br />

vary depending on patient condition and the surgical procedures being performed. There are few drugs commonly stored in<br />

anaesthetic room drug cupboards that will not be needed urgently on occasion.<br />

3 Local SOPs should exist for the safe storage of drugs (both controlled and non-controlled medicines) and fluids in operating<br />

theatre departments. These should be adequately risk-assessed and agreed by pharmacists, anaesthetists, nurses, operating<br />

department practitioners and ratified by the organisations medicines management committee. The Accountable Officer for<br />

medicines within the organisation should endorse these. 4<br />

4 Decisions about drug security in anaesthetic rooms must reflect a balance between patient safety, staff protection and security.<br />

We understand that this may mean that in defined circumstances, drug cupboards (excluding those containing Controlled<br />

Drugs) may remain unlocked when the anaesthetic room is temporarily unoccupied and the operating theatre is in use.<br />

5 Even if anaesthetic room drug cupboards cannot, in the interests of patient safety, be locked during surgical procedures,<br />

practices can be followed that may minimise medicines security risks, e.g. drugs and fluids prepared in advance for procedures<br />

can be kept in closed cupboards.<br />

6 An unoccupied anaesthetic room should ideally remain visible at all times to those in the operating theatre, usually through<br />

windows in the door.<br />

7 Anaesthetic room drug cupboards must be locked when the operating theatre is unoccupied.<br />

§<br />

For the purposes of this paper the terms drugs, medicines and fluids are used interchangeably.<br />

<br />

In this guidance, the term ‘drug cupboard’ includes all forms of drug and fluid storage, including refrigerators.

Storage of Drugs in Anaesthetic<br />

Rooms<br />

2<br />

Guidance on best practice from the RCoA and AAGBI<br />

8 It is common practice to prepare a selection of ‘emergency drugs’ that should be immediately available during the course of<br />

an anaesthetic. These will often accompany the patient from the anaesthetic room into the operating theatre but, if this is not<br />

possible, they should be stored in the anaesthetic room in a manner that maintains their immediate availability. They should be<br />

adequately labelled, and disposed of appropriately if not used.<br />

9 Certain rarely-used emergency drugs may be stored in a central location, serving the entire theatre suite, e.g. dantrolene and<br />

intralipid. Local SOPs should be compliant with relevant legislation and should ensure that the locations of these drugs are<br />

conspicuously signposted.<br />

10 We support the use of effective access control systems for all routes that allow entry into operating departments, limiting access<br />

to only those with legitimate reasons for access.<br />

References<br />

1 The safe and secure handling of medicines: a team approach. RPSGB, London 2005 (http://bit.ly/1R893Hc).<br />

2 The Health and Social Care Act 2008 (Regulated Activities) Regulations 2014 (http://bit.ly/1Zr5Lny).<br />

3 Controlled Drugs (Supervision of management and use) Regulations 2013: Information about the Regulations. DH, London 2013 (http://bit.ly/1R88CNa).<br />

4 Patient Safety Alert (NHS/PSA/D/2014/005). Stage Three: Directive: Improving medication error incident reporting and learning, 20 March 2014.<br />

MHRA and NHSE, London (http://bit.ly/1Zr6h4T).<br />

The RCoA and AAGBI would like to thank the following organisations for providing beneficial comment on this document:<br />

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS)<br />

The Association for Perioperative Practice (AfPP)<br />

The College of Operating Department Practitioners (CODP)<br />

The Association of Physicians’ Assistants (APA)<br />

The Care Quality Commission (CQC)<br />

Members of the Working Party<br />

Dr Richard Marks, Vice-President, Royal College of Anaesthetists (Chairman)<br />

Dr William Harrop-Griffiths, Council Member, Royal College of Anaesthetists<br />

Mr Mike Zeiderman, National Professional Advisor for Surgical Specialities, CQC<br />

Dr David Selwyn, Chair of Clinical Director Network<br />

Dr Kathleen Ferguson, Council Member AAGBI, Representative of SALG<br />

Ms Katharina Floss, Critical Care Pharmacist, John Radcliffe Hospital<br />

June 2016<br />

Latest review date June 2019<br />

© The Royal College of Anaesthetists (RCoA) and Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland (AAGBI) 2016<br />

Churchill House, 35 Red Lion Square, London WC1R 4SG<br />

020 7092 1500 standards@rcoa.ac.uk www.rcoa.ac.uk

SYRINGE LABELLING IN CRITICAL CARE AREAS<br />

REVIEW 2014 (updated November 2016)<br />

Since the new standard for syringe labelling was introduced in May 2003 1 , it has become apparent that a number of changes<br />

need to be made. These changes are to bring the standard in line with the change from British Approved Names (BANs) to<br />

recommended International Non-Propriety Names (rINNs) 2 , and also to bring the standard in line with the Australian/New Zealand<br />

Standard 3 and ISO Standard 4 which have superseded it. The changes are as follows:<br />

• BANs to rINNs<br />

Examples of these affecting anaesthetic drugs are:<br />

• Thiopentone to Thiopental<br />

• Lignocaine to Lidocaine<br />

• Glycopyrrolate to Glycopyrronium<br />

• Drug concentrations<br />

These were all shown on the original document as ‘mg/ml’. Correct concentrations should be used. For example:<br />

• Fentanyl micrograms/ml<br />

• Lidocaine %<br />

• Insulin units/ml<br />

• ‘Adrenaline’ is to be used, not ‘Epinephrine’ (similarly ‘Noradrenaline’, not ‘Norepinephrine’).<br />

• Suxamethonium and Adrenaline<br />

All lettering to be black with the exception of the labels for Suxamethonium and Adrenaline which shall be printed against the<br />

background colour as bold reverse plate letters within a black bar running from edge to edge of the upper half of the label, the<br />

rest of which shall display the coloured background.<br />

• Antagonists<br />

To denote a drug of opposite action, 1mm wide diagonal stripes of the designated colour, alternating with a 1 mm wide white<br />

stripe is used. The stripes should run from lower left to upper right at approximately 45 degrees. The striping should be<br />

omitted behind and below the drug name. Protamine, as an antagonist of Heparin, should be a white label with black stripes.<br />

• Anti-emetics<br />

The syringe label for this group of drugs should have the background colour Salmon 156, which is shared by the major<br />

tranquillisers.<br />

• Combinations of drugs<br />

Drugs which are supplied ready mixed in the ampoule should have a syringe label which denotes the drug name of one of the<br />

two drugs against the appropriate background in the upper half of the label, and the drug name of the second drug against the<br />

appropriate background in the lower half. For example:<br />

• Glycopyrronium and neostigmine<br />

• Lidocaine % and Adrenaline<br />

An exception to this is the label for Propofol with user-addition of Lidocaine. This label should read ‘Propofol/lidocaine’ with<br />

‘mg/ml’ for Propofol against the induction agent background (yellow).<br />

Note to users: The colours are only a guide. All syringes containing drugs must be labelled. It is important to check the drug<br />

ampoule and correctly label the syringe with the correctly texted label. Blank coloured labels are a potential source of confusion<br />

and should not be used.<br />

Dr Tim Meek<br />

Chairman Safety Committee<br />

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland<br />

1<br />

References<br />

Syringe labelling in critical care areas. RCoA Bulletin 19;May 2003:953.<br />

2<br />

Changes in names of certain medicinal substances. Chief Medical Officer, Chief Nursing Officer and Chief Pharmaceutical Officer.<br />

DoH;17 March 2004:PL/CMO2004/1.<br />

3<br />

User-applied labels for use on syringes containing drugs used during anaesthesia. Australian/New Zealand Standard;4375:1996.<br />

4 Geneva, ISO, 2008. ISO 26825:2008, Anaesthetic and respiratory equipment - User-applied labels for syringes containing drugs<br />

used during anaesthesia - Colours, design and performance.

Propofol<br />

.............................mg/ml.<br />

Induction agents<br />

Ketamine<br />

.............................mg/ml.<br />

Diazepam<br />

..........................mg/ml.<br />

Hypnotics<br />

Midazolam<br />

..........................mg/ml.<br />

.............................mg/ml.<br />

Neuromuscular blocking drugs<br />

Vecuronium<br />

.............................mg/ml.<br />

Neuromuscular blocking drug antagonist<br />

Neostigmine<br />

...............micrograms/ml.<br />

Morphine<br />

.............................mg/ml.<br />

Opioids<br />

Fentanyl<br />

................micrograms/ml.<br />

Opioid antagonist<br />

Naloxone<br />

...............micrograms/ml.<br />

Vasopressors<br />

Hypotensive agent<br />

...............micrograms/ml.<br />

Ephedrine<br />

.............................mg/ml.<br />

Labetalol<br />

..............................mg/ml.<br />

Atropine<br />

..............micrograms/ml.<br />

Anticholinergic agents<br />

Glycopyrronium<br />

.............micrograms/ml.<br />

Lidocaine<br />

...............................%.<br />

Local anaesthetics<br />

Bupivacaine<br />

...............................%.<br />

Anti-emetics<br />

Ondansetron<br />

...................mg/ml.<br />

Heparin<br />

...................units/ml.<br />

Miscellaneous<br />

Protamine<br />

...................mg/ml.<br />

Further information is available from the manufacturer or the following websites: www.astm.org and www.csa.ca<br />

Please note that colours are only a guide and the correct Pantone colour code numbers are listed on the reverse of this sheet. It<br />

is still important to check the drug ampoule and correctly label the syringe containing the drug with the correctly texted label.

STANDARD BACKGROUND COLOURS FOR USER-APPLIED<br />

SYRINGE DRUG LABELS<br />

Drug class Examples Pantone ® colour (uncoated)<br />

Anti-emetics Metoclopramide, Ondansetron Pantone ® 156 (salmon)<br />

Induction agents<br />

Thiopental, etomidate, ketamine,<br />

propofol<br />

Yellow<br />

Hypnotics Diazepam, lorazepam, midazolam Pantone ® 151 (orange)<br />

Hypnotic antagonists<br />

Depolarising neuromuscular<br />

blocking drugs<br />

Non-depolarising neuromuscular<br />

blocking drugs<br />

Neuromuscular blocking drug<br />

antagonists<br />

Flumazenil<br />

Suxamethonium<br />

Atracurium, Vecuronium<br />

Neostigmine<br />

Pantone ® 151 (orange with white<br />

diagonal stripes)<br />

Pantone ® 805 (fluorescent or warm<br />

red lettering out of black above, red<br />

below)<br />

Pantone ® 805 (fluorescent or warm<br />

red)<br />

Pantone ® (fluorescent or warm red)<br />

with white diagonal stripes<br />

Opioids Morphine, fentanyl, remifentanil Pantone ® 297 (blue)<br />

Opioid antagonists<br />

Naloxone<br />

Pantone ® 297 (blue) with white<br />

diagonal stripes<br />

Major tranquilizers Droperidol, chlorpromazine Pantone ® 156 (salmon)<br />

Vasopressors<br />

Hypotensive agents<br />

Adrenaline, ephedrine,<br />

phenylephrine<br />

Nitroprusside, nitroclycerine,<br />

phentolamine<br />

Pantone ® 256 (violet) (Adrenaline<br />

is violet out of black above, violet<br />

below)<br />

Pantone ® 256 (violet) with white<br />

diagonal stripes<br />

Local anaesthetics Lidocaine, bupivacaine Pantone ® 401 (grey)<br />

Anticholinergic agents Atropine, glycopyrronium Pantone ® 367 (green)<br />

Other agents<br />

Oxytocin, heparin, protamine,<br />

antibiotics<br />

Pantone ® transparent white<br />

(Protamine is Pantone ® transparent<br />

white with black diagonal stripes)<br />

The examples shown are representative, not restrictive. See Pantone ® Colour Formula Guide. Pantone ® is<br />

a registered trademark of Pantone, Inc.

The measurement of adult blood pressure<br />

and management of hypertension before<br />

elective surgery 2016<br />

Published by<br />

The Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain & Ireland<br />

British Hypertension Society<br />

March 2016

This guideline was originally published in Anaesthesia. If you wish to refer to this<br />

guideline, please use the following reference:<br />

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. The measurement of adult<br />

blood pressure and management of hypertension before elective surgery 2016.<br />

Anaesthesia 2016; 71: 326-337.<br />

This guideline can be viewed online via the following URL:<br />

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/anae.13348/full

Anaesthesia 2016, 71, 326–337<br />

Guidelines<br />

doi:10.1111/anae.13348<br />

The measurement of adult blood pressure and management of<br />

hypertension before elective surgery<br />

Joint Guidelines from the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland and the<br />

British Hypertension Society<br />

A. Hartle, 1 T. McCormack, 2 J. Carlisle, 3 S. Anderson, 4 A. Pichel, 5 N. Beckett, 6 T. Woodcock 7 and<br />

A. Heagerty 8<br />

1 Consultant, Departments of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, St Mary’s Hospital, London, UK, and co-Chair,<br />

Working Party on behalf of the AAGBI<br />

2 General Practitioner, Whitby Group Practice, Spring Vale Medical Centre, Whitby, UK, Honorary Reader, Hull York<br />

Medical School, UK, and co-Chair, Working Party, on behalf of the British Hypertension Society<br />

3 Consultant, Departments of Anaesthesia, Peri-operative Medicine and Intensive Care, Torbay Hospital, Torquay, UK<br />

4 Clinical Lecturer, Institute of Cardiovascular Sciences, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK and British<br />

Hypertension Society<br />

5 Consultant, Department of Anaesthesia, Manchester Royal Infirmary, Manchester, UK<br />

6 Consultant, Department of Ageing and Health, Guys’ and St Thomas’ Hospital, London, UK and British<br />

Hypertension Society<br />

7 Independent Consultant Anaesthetist, Hampshire, UK<br />

8 Professor, Department of Medicine, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK, and British Hypertension Society<br />

Summary<br />

This guideline aims to ensure that patients admitted to hospital for elective surgery are known to have blood pressures<br />

below 160 mmHg systolic and 100 mmHg diastolic in primary care. The objective for primary care is to fulfil this criterion<br />

before referral to secondary care for elective surgery. The objective for secondary care is to avoid spurious hypertensive<br />

measurements. Secondary care should not attempt to diagnose hypertension in patients who are normotensive in<br />

primary care. Patients who present to pre-operative assessment clinics without documented primary care blood pressures<br />

should proceed to elective surgery if clinic blood pressures are below 180 mmHg systolic and 110 mmHg diastolic.<br />

.................................................................................................................................................................<br />

This is a consensus document produced by members of a Working Party established by the Association of Anaesthetists<br />

of Great Britain and Ireland (AAGBI) and the British Hypertension Society (BHS). It has been seen and approved by<br />

the AAGBI Board of Directors and the BHS Executive. It is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives<br />

4.0 International License. Date of review: 2020.<br />

Accepted: 16 November 2015<br />

.................................................................................................................................................................<br />

Re-use of this article is permitted in accordance with the Creative Commons Deed, Attribution 2.5, which does not<br />

permit commercial exploitation.<br />

326 © 2016 The Authors. Anaesthesia published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd on behalf of Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland.<br />

This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License, which permits use and<br />

distribution in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited, the use is non-commercial and no modifications or adaptations are made.

Management of hypertension before elective surgery guidelines Anaesthesia 2016, 71, 326–337<br />

Recommendations<br />

•<br />

General practitioners should refer patients for elective<br />

surgery with mean blood pressures in primary<br />

care in the past 12 months less than 160 mmHg<br />

systolic and less than 100 mmHg diastolic.<br />

• Secondary care should accept referrals that document<br />

blood pressures below 160 mmHg systolic and<br />

below 100 mmHg diastolic in the past 12 months.<br />

• Pre-operative assessment clinics need not measure<br />

the blood pressure of patients being prepared for<br />

elective surgery whose systolic and diastolic blood<br />

pressures are documented below 160/100 mmHg in<br />

the referral letter from primary care.<br />

• General practitioners should refer hypertensive<br />

patients for elective surgery after the blood pressure<br />

readings are less than 160 mmHg systolic and less<br />

than 100 mmHg diastolic. Patients may be referred<br />

for elective surgery if they remain hypertensive<br />

despite optimal antihypertensive treatment or if<br />

they decline antihypertensive treatment.<br />

• Surgeons should ask general practitioners to supply<br />

primary care blood pressure readings from the last<br />

12 months if they are undocumented in the referral<br />

letter.<br />

• Pre-operative assessment staff should measure the<br />

blood pressure of patients who attend clinic without<br />

evidence of blood pressures less than<br />

160 mmHg systolic and 100 mmHg diastolic being<br />

documented by primary care in the preceding<br />

12 months. (We detail the recommended method<br />

for measuring non-invasive blood pressure accurately,<br />

although the diagnosis of hypertension is<br />

made in primary care.)<br />

• Elective surgery should proceed for patients who<br />

attend the pre-operative assessment clinic without<br />

documentation of normotension in primary care if<br />

their blood pressure is less than 180 mmHg systolic<br />

and 110 mmHg diastolic when measured in clinic.<br />

The disparity between the blood pressure thresholds<br />

for primary care (160/100 mmHg) and secondary<br />

care (180/110 mmHg) allows for a number of factors.<br />

Blood pressure reduction in primary care is based on<br />

good evidence that the rates of cardiovascular morbidity,<br />