JB Life March 2017

The Spring version of JB Life, North Jeolla's quarterly global lifestyle magazine.

The Spring version of JB Life, North Jeolla's quarterly global lifestyle magazine.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

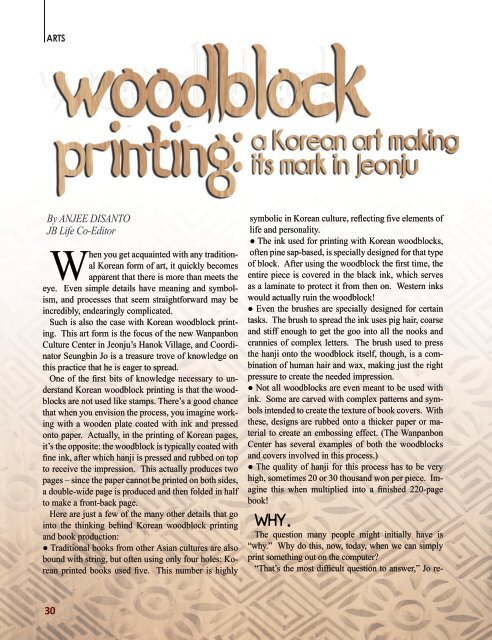

ARTS<br />

By ANJEE DISANTO<br />

<strong>JB</strong> <strong>Life</strong> Co-Editor<br />

When you get acquainted with any traditional<br />

Korean form of art, it quickly becomes<br />

apparent that there is more than meets the<br />

eye. Even simple details have meaning and symbolism,<br />

and processes that seem straightforward may be<br />

incredibly, endearingly complicated.<br />

Such is also the case with Korean woodblock printing.<br />

This art form is the focus of the new Wanpanbon<br />

Culture Center in Jeonju’s Hanok Village, and Coordinator<br />

Seungbin Jo is a treasure trove of knowledge on<br />

this practice that he is eager to spread.<br />

One of the first bits of knowledge necessary to understand<br />

Korean woodblock printing is that the woodblocks<br />

are not used like stamps. There’s a good chance<br />

that when you envision the process, you imagine working<br />

with a wooden plate coated with ink and pressed<br />

onto paper. Actually, in the printing of Korean pages,<br />

it’s the opposite: the woodblock is typically coated with<br />

fine ink, after which hanji is pressed and rubbed on top<br />

to receive the impression. This actually produces two<br />

pages – since the paper cannot be printed on both sides,<br />

a double-wide page is produced and then folded in half<br />

to make a front-back page.<br />

Here are just a few of the many other details that go<br />

into the thinking behind Korean woodblock printing<br />

and book production:<br />

● Traditional books from other Asian cultures are also<br />

bound with string, but often using only four holes: Korean<br />

printed books used five. This number is highly<br />

30<br />

symbolic in Korean culture, reflecting five elements of<br />

life and personality.<br />

● The ink used for printing with Korean woodblocks,<br />

often pine sap-based, is specially designed for that type<br />

of block. After using the woodblock the first time, the<br />

entire piece is covered in the black ink, which serves<br />

as a laminate to protect it from then on. Western inks<br />

would actually ruin the woodblock!<br />

● Even the brushes are specially designed for certain<br />

tasks. The brush to spread the ink uses pig hair, coarse<br />

and stiff enough to get the goo into all the nooks and<br />

crannies of complex letters. The brush used to press<br />

the hanji onto the woodblock itself, though, is a combination<br />

of human hair and wax, making just the right<br />

pressure to create the needed impression.<br />

● Not all woodblocks are even meant to be used with<br />

ink. Some are carved with complex patterns and symbols<br />

intended to create the texture of book covers. With<br />

these, designs are rubbed onto a thicker paper or material<br />

to create an embossing effect. (The Wanpanbon<br />

Center has several examples of both the woodblocks<br />

and covers involved in this process.)<br />

● The quality of hanji for this process has to be very<br />

high, sometimes 20 or 30 thousand won per piece. Imagine<br />

this when multiplied into a finished 220-page<br />

book!<br />

WHY.<br />

The question many people might initially have is<br />

“why.” Why do this, now, today, when we can simply<br />

print something out on the computer?<br />

“That’s the most difficult question to answer,” Jo responds.<br />

“But I think what we did in the past shows<br />

us who we are. It’s the best way to move to the future.<br />

These kind of things that are not used today are<br />

still very important and this kind of effort can make<br />

us keep our knowledge and move into another way<br />

of doing it. I think it’s very important to inherit the<br />

tradition of what we’ve been doing and let the world<br />

know about our past.”<br />

Then, why in Jeonju?<br />

The Wanpanbon Culture Center belongs to Jeonju’s<br />

city government and opened on January 1st this<br />

year, focused on making woodblocks and printed<br />

books in the ways of old. (Before this, much of the<br />

group’s work happened via the Woodblock Culture<br />

Experience Center down the street, which still holds<br />

classes in woodblock printing.) The name itself contains<br />

a valuable bit of history. In the time of the Joseon<br />

Dynasty, Jeonju was one of three major hubs of<br />

the production of woodblock-printed books, and the<br />

popular books from this location were called wanpanbon.<br />

Many of them were novels that sprang from<br />

the desire to read Korean stories that had only been<br />

oral before, while in other regions prints were made<br />

largely of historical and important Chinese texts.<br />

With its history in mind, the new center focuses<br />

on the entire process as it existed in old days, from<br />

cutting the wood, to making the boards, engraving<br />

them, choosing the paper, and printing a final product.<br />

Specifically, these days their work involves reproducing<br />

important books from the age of woodblock<br />

printing. This is partially so that people can<br />

see the history of how these works were made. Also,<br />

while many historic woodblocks still exist, there is<br />

rarely a complete set to represent a book. The center<br />

seeks to fill in the gaps and produce full print-capable<br />

sets.<br />

Up until last year, the group behind the center was<br />

working on a story book called “The History of the<br />

Three Kingdoms,” created in the Joseon Dynasty.<br />

The three different countries or kingdoms are still<br />

considered as one foundation for the Korean culture.<br />

Gumi County in Gyeongsan Province – the place<br />

where the text originated – wanted to reproduce all<br />

the woodblocks related to the story as part of the history<br />

of a local temple. Thus, the group and seven<br />

gaksu (woodblock engravers) set out on the daunting<br />

two-year voyage of making and printing this historic<br />

volume. Wanbanpon’s director, Esan Ahn Junyoung,<br />

was himself one of the engravers, while the group<br />

behind the center was asked to do the actual printing<br />

of the book. The process required 110 woodblocks<br />

on both sides, Seungbin explained. About a year of<br />

the work was required just for engraving them, with<br />

another two months just for the actual printing part.<br />

g<br />

Jeonbuk <strong>Life</strong> 31