Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

<strong>Evys</strong> <strong>Martin</strong>’s<br />

Chemistry<br />

<strong>Notebook</strong>

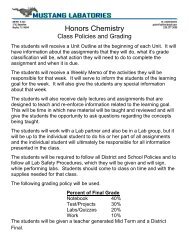

Honors Chemistry<br />

Class Policies and Grading<br />

The students will receive a Unit Outline at the beginning of each Unit. It will<br />

have information about the assignments that they will do, what it’s grade<br />

classification will be, what action they will need to do to complete the<br />

assignment and when it is due.<br />

The students will receive a Weekly Memo of the activities they will be<br />

responsible for that week. It will serve to inform the students of the learning<br />

goal for the week. It will also give the students any special information<br />

about that week.<br />

The students will also receive daily lectures and assignments that are<br />

designed to teach and re-enforce information related to the learning goal.<br />

This will be time in which new material will be taught and reviewed and will<br />

give the students the opportunity to ask questions regarding the concepts<br />

being taught.<br />

The students will work with a Lab partner and also be in a Lab group, but it<br />

will be up to the individual student to do his or her part of all assignments<br />

and the individual student will ultimately be responsible for all information<br />

presented in the class.<br />

The students will be required to follow all District and School Policies and to<br />

follow all Lab Safety Procedures, which they will be given and will sign,<br />

while performing labs. Students should come to class on time and with the<br />

supplies needed for that class.<br />

The following grading policy will be used.<br />

Percent of <strong>Final</strong> Grade<br />

<strong>Notebook</strong> 40%<br />

Test/Projects 30%<br />

Labs/Quizzes 20%<br />

Work 10%<br />

The students will be given a teacher generated Mid Term and a District<br />

<strong>Final</strong>.

Unit 1<br />

Measurement Lab<br />

Separation of Mixtures Lab with Lab Write Up<br />

Unit 2<br />

Flame Test Lab<br />

Nuclear Decay Lab<br />

Element Marketing Project<br />

Unit 3<br />

Golden Penny Lab with Lab Write Up<br />

Molecular Geometry<br />

Research Presentation on a Chemical<br />

Mid Term<br />

Unit 4<br />

Double Displacement Lab<br />

Stoichiometry Lab with Lab Write Up<br />

Mole Educational Demonstration Project<br />

Unit 5<br />

Gas Laws Lab with Lab Write Up<br />

States of Matter Lab<br />

Teach a Gas Law Project<br />

Unit 6<br />

Dilutions Lab<br />

Titration Lab<br />

District <strong>Final</strong>

Unit 1 (22 days)<br />

Chapter 1 Introduction to Chemistry<br />

Honors Chemistry<br />

2016/2017 Syllabus<br />

3 days<br />

1.1 The Scope of Chemistry 1.3 Thinking Like a Scientist<br />

1.2 Chemistry and You 1.4 Problem Solving in Chemistry<br />

Chapter 2 Matter and Change<br />

2.1 Properties of Matter 2.3 Elements and Compounds<br />

2.2 Mixtures 2.4 Chemical Reactions<br />

Chapter 3 Scientific Measurement<br />

9 days<br />

10 days<br />

3.1 Using and Expressing Measurements 3.3 Solving Conversion Problems<br />

3.2 Units of Measurement<br />

Unit 2 (15 days)<br />

Chapter 4 Atomic Structure<br />

5 days<br />

4.1 Defining the Atom 4.3 Distinguishing Among Atoms<br />

4.2 Structure of the Nuclear Atom<br />

Chapter 5 Electrons in Atoms<br />

5 days<br />

5.1 Revising the Atomic Model 5.2 Electron Arrangement in Atoms<br />

5.3 Atomic Emission Spectrum and the Quantum Mechanical Model<br />

Chapter 6 The Periodic Table<br />

6.1 Organizing the Elements 6.3 Periodic Trends<br />

6.2 Classifying Elements<br />

Unit 3 (22 days)<br />

Chapter 25 Nuclear Chemistry<br />

25.1 Nuclear Radiation 25.3 Fission and Fusion<br />

25.2 Nuclear Transformations 25.4 Radiation in Your Life<br />

Chapter 7 Ionic and Metallic Bonding<br />

7.1 Ions 7.3 Bonding in Metals<br />

7.2 Ionic Bonds and Ionic Compounds<br />

Chapter 8 Covalent Bonding<br />

5 days<br />

6 days<br />

8 days<br />

8 days<br />

8.1 Molecular Compounds 8.3 Bonding Theories<br />

8.2 The Nature of Covalent Bonding 8.4 Polar Bonds and Molecules<br />

Unit 4 (14 days)<br />

Chapter 9 Chemical Names and Formulas<br />

6 days<br />

9.1 Naming Ions 9.3 Naming & Writing Formulas Molecular Compounds<br />

9.2 Naming and Writing Formulas for Ionic Compounds 9.4 Names for Acids and Bases<br />

Chapter 22 Hydrocarbons Compounds<br />

22.1 Hydrocarbons 22.4 Hydrocarbon Rings<br />

Chapter 23 Functional Groups<br />

4 days<br />

4 days<br />

23.1 Introduction to Functional Groups 23.4 Alcohols, Ethers, and Amines

Unit 5 (28 days)<br />

Chapter 10 Chemical Quantities 8 days<br />

10.1 The Mole: A Measurement of Matter 10.3 % Composition & Chem. Formulas<br />

10.2 Mole-Mass and Mole-Volume Relationships<br />

Chapter 11 Chemical Reactions 8 days<br />

11.1 Describing Chemical Reactions 11.3 Reactions in Aqueous Solutions<br />

11.2 Types of Chemical Reactions<br />

Chapter 12 Stoichiometry 12 days<br />

12.1 The Arithmetic of Equations 12.3 Limiting Reagent and % Yield<br />

12.2 Chemical Calculations<br />

Unit 6 (22 days)<br />

Chapter 13 States of Matter 6 days<br />

13.1 The Nature of Gases 13.3 The Nature of Solids<br />

13.2 The Nature of Liquids 13.4 Changes in State<br />

Chapter 14 The Behavior of Gases 10 days<br />

14.1 Properties of Gases 14.3 Ideal Gases<br />

14.2 The Gas Laws 14.4 Gases: Mixtures and Movement<br />

Chapter 15 Water and Aqueous Systems 6 days<br />

15.1 Water and its Properties 15.3 Heterogeneous Aqueous Systems<br />

15.2 Homogeneous Aqueous Systems<br />

Unit 7 (18 days)<br />

Chapter 16 Solutions 8 days<br />

16.1 Properties of Solutions 16.3 Colligative Properties of Solutions<br />

16.2 Concentrations of Solutions 16.4 Calc. Involving Colligative Property<br />

Chapter 17 Thermochemistry 5 days<br />

17.1 The Flow of Energy 17.3 Heat in Changes of State<br />

17.2 Measuring and Expressing Enthalpy Change 17.4 Calculating Heats in Reactions<br />

Chapter 18 Reaction Rates and Equilibrium 5 days<br />

18.1 Rates of Reactions 18.3 Reversible Reaction & Equilibrium<br />

18.2 The Progress of Chemical Reactions 18.5 Free Energy and Entropy<br />

Unit 8 (14 days)<br />

Chapter 19 Acid and Bases 10 days<br />

19.1 Acid-Base Theories 19.4 Neutralization Reactions<br />

19.2 Hydrogen Ions and Acidity 19.5 Salts in Solutions<br />

19.3 Strengths of Acids and Bases<br />

Chapter 20 Oxidation-Reduction Reactions 4 days<br />

20.1 The Meaning of Oxidation and Reduction 20.3 Describing Redox Equations<br />

20.2 Oxidation Numbers

Lorenzo Walker Technical High School<br />

MUSTANG LABORATORIES<br />

Chemistry Safety<br />

Safety in the MUSTANG LABORATORIES - Chemistry Laboratory<br />

Working in the chemistry laboratory is an interesting and rewarding experience. During your labs, you will be actively<br />

involved from beginning to end—from setting some change in motion to drawing some conclusion. In the laboratory, you<br />

will be working with equipment and materials that can cause injury if they are not handled properly.<br />

However, the laboratory is a safe place to work if you are careful. Accidents do not just happen; they are caused—by<br />

carelessness, haste, and disregard of safety rules and practices. Safety rules to be followed in the laboratory are listed<br />

below. Before beginning any lab work, read these rules, learn them, and follow them carefully.<br />

General<br />

1. Be prepared to work when you arrive at the lab. Familiarize yourself with the lab procedures before beginning the lab.<br />

2. Perform only those lab activities assigned by your teacher. Never do anything in the laboratory that is not called for in<br />

the laboratory procedure or by your teacher. Never work alone in the lab. Do not engage in any horseplay.<br />

3. Work areas should be kept clean and tidy at all times. Only lab manuals and notebooks should be brought to the work<br />

area. Other books, purses, brief cases, etc. should be left at your desk or placed in a designated storage area.<br />

4. Clothing should be appropriate for working in the lab. Jackets, ties, and other loose garments should be removed. Open<br />

shoes should not be worn.<br />

5. Long hair should be tied back or covered, especially in the vicinity of open flame.<br />

6. Jewelry that might present a safety hazard, such as dangling necklaces, chains, medallions, or bracelets should not be<br />

worn in the lab.<br />

7. Follow all instructions, both written and oral, carefully.<br />

8. Safety goggles and lab aprons should be worn at all times.<br />

9. Set up apparatus as described in the lab manual or by your teacher. Never use makeshift arrangements.<br />

10. Always use the prescribed instrument (tongs, test tube holder, forceps, etc.) for handling apparatus or equipment.<br />

11. Keep all combustible materials away from open flames.<br />

12. Never touch any substance in the lab unless specifically instructed to do so by your teacher.<br />

13. Never put your face near the mouth of a container that is holding chemicals.<br />

14. Never smell any chemicals unless instructed to do so by your teacher. When testing for odors, use a wafting motion to<br />

direct the odors to your nose.<br />

15. Any activity involving poisonous vapors should be conducted in the fume hood.<br />

16. Dispose of waste materials as instructed by your teacher.<br />

17. Clean up all spills immediately.<br />

18. Clean and wipe dry all work surfaces at the end of class. Wash your hands thoroughly.<br />

19. Know the location of emergency equipment (first aid kit, fire extinguisher, fire shower, fire blanket, etc.) and how to use them.<br />

20. Report all accidents to the teacher immediately.<br />

Handling Chemicals<br />

21. Read and double check labels on reagent bottles before removing any reagent. Take only as much reagent as you<br />

need.<br />

22. Do not return unused reagent to stock bottles.<br />

23. When transferring chemical reagents from one container to another, hold the containers out away from your body.<br />

24. When mixing an acid and water, always add the acid to the water.<br />

25. Avoid touching chemicals with your hands. If chemicals do come in contact with your hands, wash them immediately.<br />

26. Notify your teacher if you have any medical problems that might relate to lab work, such as allergies or asthma.<br />

27. If you will be working with chemicals in the lab, avoid wearing contact lenses. Change to glasses, if possible, or notify<br />

the teacher.<br />

Handling Glassware<br />

28. Glass tubing, especially long pieces, should be carried in a vertical position to minimize the likelihood of breakage and<br />

to avoid stabbing anyone.<br />

29. Never handle broken glass with your bare hands. Use a brush and dustpan to clean up broken glass. Dispose of the<br />

glass as directed by your teacher.

30. Always lubricate glassware (tubing, thistle tubes, thermometers, etc.) with water or glycerin before attempting to insert<br />

it into a rubber stopper.<br />

31. Never apply force when inserting or removing glassware from a stopper. Use a twisting motion. If a piece of glassware<br />

becomes "frozen" in a stopper, take it to your teacher.<br />

32. Do not place hot glassware directly on the lab table. Always use an insulating pad of some sort.<br />

33. Allow plenty of time for hot glass to cool before touching it. Hot glass can cause painful burns. (Hot glass looks cool.)<br />

Heating Substances<br />

34. Exercise extreme caution when using a gas burner. Keep your head and clothing away from the flame.<br />

35. Always turn the burner off when it is not in use.<br />

36. Do not bring any substance into contact with a flame unless instructed to do so.<br />

37. Never heat anything without being instructed to do so.<br />

38. Never look into a container that is being heated.<br />

39. When heating a substance in a test tube, make sure that the mouth of the tube is not pointed at yourself or anyone<br />

else.<br />

40. Never leave unattended anything that is being heated or is visibly reacting.<br />

First Aid in the MUSTANG LABORATORIES - Chemistry Laboratory<br />

Accidents do not often happen in well-equipped chemistry laboratories if students understand safe laboratory procedures<br />

and are careful in following them. When an occasional accident does occur, it is likely to be a minor one.<br />

The instructor will assist in treating injuries such as minor cuts and burns. However, for some types of injuries, you must<br />

take action immediately. The following information will be helpful to you if an accident occurs.<br />

1. Shock. People who are suffering from any severe injury (for example, a bad burn or major loss of blood) may be in a<br />

state of shock. A person in shock is usually pale and faint. The person may be sweating, with cold, moist skin and a weak,<br />

rapid pulse. Shock is a serious medical condition. Do not allow a person in shock to walk anywhere—even to the campus<br />

security office. While emergency help is being summoned, place the victim face up in a horizontal position, with the feet<br />

raised about 30 centimeters. Loosen any tightly fitting clothing and keep him or her warm.<br />

2. Chemicals in the Eyes. Getting any kind of a chemical into the eyes is undesirable, but certain chemicals are<br />

especially harmful. They can destroy eyesight in a matter of seconds. Because you will be wearing safety goggles at all<br />

times in the lab, the likelihood of this kind of accident is remote. However, if it does happen, flush your eyes with water<br />

immediately. Do NOT attempt to go to the campus office before flushing your eyes. It is important that flushing with water<br />

be continued for a prolonged time—about 15 minutes.<br />

3. Clothing or Hair on Fire. A person whose clothing or hair catches on fire will often run around hysterically in an<br />

unsuccessful effort to get away from the fire. This only provides the fire with more oxygen and makes it burn faster. For<br />

clothing fires, throw yourself to the ground and roll around to extinguish the flames. For hair fires, use a fire blanket to<br />

smother the flames. Notify campus security immediately.<br />

4. Bleeding from a Cut. Most cuts that occur in the chemistry laboratory are minor. For minor cuts, apply pressure to the<br />

wound with a sterile gauze. Notify campus security of all injuries in the lab. If the victim is bleeding badly, raise the<br />

bleeding part, if possible, and apply pressure to the wound with a piece of sterile gauze. While first aid is being given,<br />

someone else should notify the campus security officer.<br />

5. Chemicals in the Mouth. Many chemicals are poisonous to varying degrees. Any chemical taken into the mouth<br />

should be spat out and the mouth rinsed thoroughly with water. Note the name of the chemical and notify the campus<br />

office immediately. If the victim swallows a chemical, note the name of the chemical and notify campus security<br />

immediately.<br />

If necessary, the campus security officer or administrator will contact the Poison Control Center, a hospital emergency<br />

room, or a physician for instructions.<br />

6. Acid or Base Spilled on the Skin.<br />

Flush the skin with water for about 15 minutes. Take the victim to the campus office to report the injury.<br />

7. Breathing Smoke or Chemical Fumes.<br />

All experiments that give off smoke or noxious gases should be conducted in a well-ventilated fume hood. This will make<br />

an accident of this kind unlikely. If smoke or chemical fumes are present in the laboratory, all persons—even those who<br />

do not feel ill—should leave the laboratory immediately. Make certain that all doors to the laboratory are closed after the<br />

last person has left. Since smoke rises, stay low while evacuating a smoke-filled room. Notify campus security<br />

immediately.

MUSTANG LABORATORIES<br />

COMMITMENT TO SAFETY IN THE LABORATORY<br />

As a student enrolled in Chemistry at Lorenzo Walker Technical High<br />

School, I agree to use good laboratory safety practices at all times. I<br />

also agree that I will:<br />

1. Conduct myself in a professional manner, respecting both my personal safety and the safety of<br />

others in the laboratory.<br />

2. Wear proper and approved safety glasses or goggles in the laboratory at all times.<br />

3. Wear sensible clothing and tie back long hair in the laboratory. Understand that open-toed shoes<br />

pose a hazard during laboratory classes and that contact lenses are an added safety risk.<br />

4. Keep my lab area free of clutter during an experiment.<br />

5. Never bring food or drink into the laboratory, nor apply makeup within the laboratory.<br />

6. Be aware of the location of safety equipment such as the fire extinguisher, eye wash station, fire<br />

blanket, first aid kit. Know the location of the nearest telephone and exits.<br />

7. Read the assigned lab prior to coming to the laboratory.<br />

8. Carefully read all labels on all chemical containers before using their contents, remove a small<br />

amount of reagent properly if needed, do not pour back the unused chemicals into the original<br />

container.<br />

9. Dispose of chemicals as directed by the instructor only. At no time will I pour anything down the<br />

sink without prior instruction.<br />

10. Never inhale fumes emitted during an experiment. Use the fume hood when instructed to do so.<br />

11. Report any accident immediately to the instructor, including chemical spills.<br />

12. Dispose of broken glass and sharps only in the designated containers.<br />

13. Clean my work area and all glassware before leaving the laboratory.<br />

14. Wash my hands before leaving the laboratory.<br />

NAME __________________________<br />

<strong>Evys</strong> <strong>Martin</strong><br />

PERIOD ________________________<br />

3<br />

PARENT NAME ____________________________<br />

Ismary Reyes<br />

PARENT NUMBER _________________________<br />

2393841157<br />

SIGNATURE ____________________________<br />

DATE ____________________________________<br />

8-25-16

Chapter 1<br />

Unit 1<br />

Introduction to Chemistry<br />

The students will learn why and how to solve problems using<br />

chemistry.<br />

Identify what is science, what clearly is not science, and what superficially<br />

resembles science (but fails to meet the criteria for science).<br />

Students will identify a phenomenon as science or not science.<br />

Science<br />

Observation<br />

Inference<br />

Hypothesis<br />

Identify which questions can be answered through science and which<br />

questions are outside the boundaries of scientific investigation, such as<br />

questions addressed by other ways of knowing, such as art, philosophy, and<br />

religion.<br />

Students will differentiate between problems and/or phenomenon that can and<br />

those that cannot be explained or answered by science.<br />

Students will differentiate between problems and/or phenomenon that can and<br />

those that cannot be explained or answered by science.<br />

Observation<br />

Inference<br />

Hypothesis<br />

Theory<br />

Controlled experiment<br />

Describe how scientific inferences are drawn from scientific observations<br />

and provide examples from the content being studied.<br />

Students will conduct and record observations.<br />

Students will make inferences.<br />

Students will identify a statement as being either an observation or inference.<br />

Students will pose scientific questions and make predictions based on<br />

inferences.<br />

Inference<br />

Observation<br />

Hypothesis<br />

Controlled experiment<br />

Identify sources of information and assess their reliability according to the<br />

strict standards of scientific investigation.<br />

Students will compare and assess the validity of known scientific information<br />

from a variety of sources:

Print vs. print<br />

Online vs. online<br />

Print vs. online<br />

Students will conduct an experiment using the scientific method and compare<br />

with other groups.<br />

Controlled experiment<br />

Investigation<br />

Peer Review<br />

Accuracy<br />

Precision<br />

Percentage Error<br />

Chapter 2<br />

Matter and Change<br />

The students will learn what properties are used to describe<br />

matter and how matter can change its form.<br />

Differentiate between physical and chemical properties and physical and<br />

chemical changes of matter.<br />

Students will be able to identify physical and chemical properties of various<br />

substances.<br />

Students will be able to identify indicators of physical and chemical changes.<br />

Students will be able to calculate density.<br />

mass<br />

physical property<br />

volume<br />

chemical property<br />

vapor<br />

extensive property<br />

Chapter 3<br />

mixture<br />

intensive property<br />

solution<br />

element<br />

compound<br />

Scientific Measurements<br />

The students will be able to solve conversion problems using<br />

measurements.<br />

Determine appropriate and consistent standards of measurement for the<br />

data to be collected in a survey or experiment.<br />

Students will participate in activities to collect data using standardized<br />

measurement.<br />

Students will be able to manipulate/convert data collected and apply the data<br />

to scientific situations.<br />

Scientific notation<br />

International System of Units (SI)<br />

Significant figures<br />

Accepted value<br />

Experimental value<br />

Percent error<br />

Dimensional analysis

Determine appropriate and consistant standards of measurements for the data to be collected in a survey<br />

or equipment.<br />

K-ing H-enry D-ied B-ecause D-rank C-hocolate M-ilk<br />

K=ilograms<br />

H=ectares<br />

D=eca<br />

B=ase<br />

D=ecimiter<br />

C=entemiter<br />

M=illimiter<br />

one centemiter squared equals i milliliter.

To use the Stair-Step method, find the prefix the original measurement starts with. (ex. milligram)<br />

If there is no prefix, then you are starting with a base unit.<br />

Find the step which you wish to make the conversion to. (ex. decigram)<br />

Count the number of steps you moved, and determine in which direction you moved (left or right).<br />

The decimal in your original measurement moves the same number of places as steps you moved and in the<br />

same direction. (ex. milligram to decigram is 2 steps to the left, so 40 milligrams = .40 decigrams)<br />

If the number of steps you move is larger than the number you have, you will have to add zeros to hold the<br />

places. (ex. kilometers to meters is three steps to the right, so 10 kilometers would be equal to 10,000 m)<br />

That’s all there is to it! You need to be able to count to 6, and know your left from your right!<br />

1) Write the equivalent<br />

a) 5 dm =_______m .5<br />

b) 4 mL = ______L .004 c) 8 g = _______mg 8000<br />

d) 9 mg =_______g 0.009<br />

e) 2 mL = ______L .oo2 f) 6 kg = _____g 0006<br />

g) 4 cm =_______m 0.04 h) 12 mg = ______ 0.012g i) 6.5 cm 3 = _______L 0006.5<br />

j) 7.02 mL =_____cm 702.0<br />

3 k) .03 hg = _______ 0.3 dg l) 6035 mm _____cm 603.5<br />

m) .32 m = _______cm .032<br />

n) 38.2 g = 0.0382 _____kg

2. One cereal bar has a mass of 37 g. What is the mass of 6 cereal bars? Is that more than or less<br />

than 1 kg? Explain your answer.<br />

The mass of the bars will stay the same but the weight will change<br />

3. Wanda needs to move 110 kg of rocks. She can carry l0 hg each trip. How many trips must she<br />

make? Explain your answer.<br />

she will need to go 110 times, one kilogram aquals 1 hg<br />

4. Dr. O is playing in her garden again She needs 1 kg of potting soil for her plants. She has 750 g.<br />

How much more does she need? Explain your answer.<br />

she needs 250 grams<br />

5. Weather satellites orbit Earth at an altitude of 1,400,000 meters. What is this altitude in kilometers?<br />

1400 kilometers.<br />

6. Which unit would you use to measure the capacity? Write milliliter or liter.<br />

a) a bucket __________ liter<br />

b) a thimble __________<br />

milliliter<br />

c) a water storage tank__________ liter<br />

d) a carton of juice__________ liter<br />

7. Circle the more reasonable measure:<br />

a) length of an ant 5mm or 5cm<br />

5mm<br />

b) length of an automobile 5 m or 50 m<br />

5m<br />

c) distance from NY to LA 450 km or 4,500 km<br />

4500km<br />

d) height of a dining table 75 mm or 75 cm<br />

75cm<br />

8. Will a tablecloth that is 155 cm long cover a table that is 1.6 m long? Explain your answer.<br />

no<br />

9. A dollar bill is 15.6 cm long. If 200 dollar bills were laid end to end, how many meters long would<br />

the line be?<br />

3.21m<br />

10. The ceiling in Jan’s living room is 2.5 m high. She has a hanging lamp that hangs down 41 cm.<br />

Her husband is exactly 2 m tall. Will he hit his head on the hanging lamp? Why or why not?<br />

he wont hit the lamp, 1m=100cm so 41cm is 9cm away from<br />

being half a meter.

Using SI Units<br />

Match the terms in Column II with the descriptions in Column I. Write the letters of the correct term in<br />

the blank on the left.<br />

Column I Column II<br />

_____ e 1. distance between two points<br />

a. time<br />

_____ 2. SI unit of length<br />

m_____ 3. tool used to measure length<br />

_____ g 4. units obtained by combining other units<br />

_____ b 5. amount of space occupied by an object<br />

h<br />

_____ 6. unit used to express volume<br />

_____ j 7. SI unit of mass<br />

_____ d 8. amount of matter in an object<br />

_____ j 9. mass per unit of volume<br />

_____ o 10. temperature scale of most laboratory thermometers<br />

_____ 11. instrument used to measure mass<br />

_____ a 12. interval between two events<br />

_____ j 13. SI unit of temperature<br />

i_____ 14. SI unit of time<br />

_____ n 15. instrument used to measure temperature<br />

b. volume<br />

c. mass<br />

d. density<br />

e. meter<br />

f. kilogram<br />

g. derived<br />

h. liter<br />

i. second<br />

j. Kelvin<br />

k. length<br />

1. balance<br />

m. meterstick<br />

n. thermometer<br />

o. Celsius<br />

Circle the two terms in each group that are related. Explain how the terms are related.<br />

16. Celsius degree, mass, Kelvin _____________________________________________________<br />

these all measure the temp and movement of the<br />

________________________________________________________________________________<br />

atoms in something. the mass will impact the temp.<br />

17. balance, second, mass __________________________________________________________<br />

________________________________________________________________________________<br />

18. kilogram, liter, cubic centimeter __________________________________________________<br />

these can be used to measure the interior of<br />

________________________________________________________________________________<br />

something.<br />

19. time, second, distance __________________________________________________________<br />

these are all related, the distance to travel on<br />

________________________________________________________________________________<br />

such time equals speed.<br />

20. decimeter, kilometer, Kelvin _____________________________________________________<br />

kalvin dont belong, the others are<br />

________________________________________________________________________________<br />

distances.

1. How many meters are in one kilometer? __________ 100<br />

2. What part of a liter is one milliliter? __________ a 4th<br />

3. How many grams are in two dekagrams? __________<br />

20<br />

4. If one gram of water has a volume of one milliliter, what would the mass of one liter of water be in<br />

kilograms?__________ .001<br />

5. What part of a meter is a decimeter? __________<br />

10th<br />

In the blank at the left, write the term that correctly completes each statement. Choose from the terms<br />

listed below.<br />

Metric SI standard ten<br />

prefixes ten tenth<br />

6. An exact quantity that people agree to use for comparison is a ______________ standard ten .<br />

7. The system of measurement used worldwide in science is _______________ metric .<br />

8. SI is based on units of _______________ ten<br />

.<br />

9. The system of measurement that was based on units of ten was the tenth _______________ system.<br />

10. In SI, _______________ prefixes are used with the names of the base unit to indicate the multiple of ten<br />

that is being used with the base unit.<br />

11. The prefix deci- means _______________ ten<br />

.

Standards of Measurement<br />

Fill in the missing information in the table below.<br />

Prefix<br />

milli<br />

S.I prefixes and their meanings<br />

Meaning<br />

0.001<br />

0.01<br />

milli<br />

deci- 0.1<br />

deci<br />

10<br />

hecto- 100<br />

milli<br />

1000<br />

Circle the larger unit in each pair of units.<br />

1. millimeter, kilometer 4. centimeter, millimeter<br />

2. decimeter, dekameter 5. hectogram, kilogram<br />

3. hectogram, decigram<br />

6. In SI, the base unit of length is the meter. Use this information to arrange the following units of<br />

measurement in the correct order from smallest to largest.<br />

Write the number 1 (smallest) through 7 - (largest) in the spaces provided.<br />

_____ 7 a. kilometer<br />

_____ 3 b. centimeter<br />

_____ 5 c. meter<br />

1<br />

_____ d. dekameter<br />

6<br />

_____ e. hectometer<br />

2<br />

_____ f. millimeter<br />

_____<br />

4<br />

g. decimeter<br />

Use your knowledge of the prefixes used in SI to answer the following questions in the spaces<br />

provided.<br />

7. One part of the Olympic games involves an activity called the decathlon. How many events do you<br />

think make up the decathlon?_____________________________________________________<br />

10<br />

10 years<br />

8. How many years make up a decade? _______________________________________________<br />

100 years<br />

9. How many years make up a century? ______________________________________________<br />

1000<br />

10. What part of a second do you think a millisecond is? __________________________________

The Learning Goal for this assignment is:<br />

determine appropriate and consistent standards of measurement of the<br />

data to be collected in a survey.<br />

Notes Section<br />

to make the exponent smaller change the decimal<br />

on the first number.<br />

1. 7,485 6. 1.683<br />

2. 884.2 7. 3.622<br />

3. 0.00002887 8. 0.00001735<br />

4. 0.05893 9. 0.9736<br />

5. 0.006162 10. 0.08558<br />

11. 6.633 X 10−⁴ 16. 1.937 X 10⁴<br />

12. 4.445 X 10−⁴ 17. 3.457 X 10⁴<br />

13. 2.182 X 10−³ 18. 3.948 X 10−⁵<br />

14. 4.695 X 10² 19. 8.945 X 10⁵<br />

15. 7.274 X 10⁵ 20. 6.783 X 10²

SCIENTIFIC NOTATION RULES<br />

How to Write Numbers in Scientific Notation<br />

Scientific notation is a standard way of writing very large and very small numbers so that they're<br />

easier to both compare and use in computations. To write in scientific notation, follow the form<br />

N X 10 ᴬ<br />

where N is a number between 1 and 10, but not 10 itself, and A is an integer (positive or negative<br />

number).<br />

RULE #1: Standard Scientific Notation is a number from 1 to 9 followed by a decimal and the<br />

remaining significant figures and an exponent of 10 to hold place value.<br />

Example:<br />

5.43 x 10 2 = 5.43 x 100 = 543<br />

8.65 x 10 – 3 = 8.65 x .001 = 0.00865<br />

****54.3 x 10 1 is not Standard Scientific Notation!!!<br />

RULE #2: When the decimal is moved to the Left the exponent gets Larger, but the value of the<br />

number stays the same. Each place the decimal moves Changes the exponent by one (1). If you<br />

move the decimal to the Right it makes the exponent smaller by one (1) for each place it is moved.<br />

Example:<br />

6000. x 10 0 = 600.0 x 10 1 = 60.00 x 10 2 = 6.000 x 10 3 = 6000<br />

(Note: 10 0 = 1)<br />

All the previous numbers are equal, but only 6.000 x 10 3 is in proper Scientific Notation.

RULE #3: To add/subtract in scientific notation, the exponents must first be the same.<br />

Example:<br />

(3.0 x 10 2 ) + (6.4 x 10 3 ); since 6.4 x 10 3 is equal to 64. x 10 2 . Now add.<br />

(3.0 x 10 2 )<br />

+ (64. x 10 2 )<br />

67.0 x 10 2 = 6.70 x 10 3 = 6.7 x 10 3<br />

67.0 x 10 2 is mathematically correct, but a number in standard scientific notation can only<br />

have one number to the left of the decimal, so the decimal is moved to the left one place and<br />

one is added to the exponent.<br />

Following the rules for significant figures, the answer becomes 6.7 x 10 3 .<br />

RULE #4: To multiply, find the product of the numbers, then add the exponents.<br />

Example:<br />

(2.4 x 10 2 ) (5.5 x 10 –4 ) = ? [2.4 x 5.5 = 13.2]; [2 + -4 = -2], so<br />

(2.4 x 10 2 ) (5.5 x 10 –4 ) = 13.2 x 10 –2 = 1.3 x 10 – 1<br />

RULE #5: To divide, find the quotient of the number and subtract the exponents.<br />

Example:<br />

(3.3 x 10 – 6 ) / (9.1 x 10 – 8 ) = ? [3.3 / 9.1 = .36]; [-6 – (-8) = 2], so<br />

(3.3 x 10 – 6 ) / (9.1 x 10 – 8 ) = .36 x 10 2 = 3.6 x 10 1

Convert each number from Scientific Notation to real numbers:<br />

1. 7.485 X 10³ 6. 1.683 X 10⁰<br />

7485. 1.683<br />

2. 8.842 X 10² 7. 3.622 10⁰<br />

884.2 3.622<br />

3. 2.887 X 10−⁵ 8. 1.735 X 10−⁵<br />

.00002887 .00001735<br />

4. 5.893 X 10−² 9. 9.736 X 10−¹<br />

.005893<br />

.097736<br />

5. 6.162 X 10−³ 10. 8.558 X 10−²<br />

.008558<br />

.000612<br />

Convert each number from a real number to Scientific Notation:<br />

1.937x10<br />

11. 0.0006633 16. 1,937,000<br />

6.633 -4<br />

7.274x10 2 6.783x10 2<br />

12. 0.0004445 17. 34,570<br />

4.445x10 -4<br />

3.457x10<br />

13. 0.002182 18. 0.00003948<br />

2.182x10 -3<br />

3.948 -5<br />

14. 469.5 19. 894,500<br />

4.695x10 2<br />

8.945x10 2<br />

15. 727,400 20. 678.3

The Learning Goal for this assignment is:<br />

determine appropriate and consistant standards of measurement<br />

for the data to be collected in survey or experiment.<br />

Notes Section:<br />

non-zeros are always significant bro.<br />

any zero between significant digits, than those are significant.<br />

after a decimal, if its before significant its not valuable, if its after then it is.<br />

Question Sig Figs Question Add & Subtract Question Multiple & Divide<br />

1 4 1 55.36 1 20,000<br />

2 4 2 84.2 2 94<br />

3 3 3 115.4 3 300<br />

4 3 4 0.8 4 7<br />

5 4 5 245.53 5 62<br />

6 3 6 34.5 6 0.005<br />

7 3 7 74.0 7 4,000<br />

8 2 8 53.287 8 3,900,000<br />

9 2 9 54.876 9 2<br />

10 2 10 40.19 10 30,000,000<br />

11 3 11 7.7 11 1,200<br />

12 2 12 67.170 12 0.2<br />

13 3 13 81.0 13 0.87<br />

14 4 14 73.290 14 0.049<br />

15 4 15 29.789 15 2,000<br />

16 3 16 39.53 16 0.5<br />

17 4 17 70.58 17 1.9<br />

18 2 18 86.6 18 0.05<br />

19 2 19 64.990 19 230<br />

20 1 20 36.0 20 460,000

Significant Figures Rules<br />

There are three rules on determining how many significant figures are in a<br />

number:<br />

1. Non-zero digits are always significant.<br />

2. Any zeros between two significant digits are significant.<br />

3. A final zero or trailing zeros in the DECIMAL PORTION ONLY are<br />

significant.<br />

Please remember that, in science, all numbers are based upon measurements (except for a very few<br />

that are defined). Since all measurements are uncertain, we must only use those numbers that are<br />

meaningful.<br />

Not all of the digits have meaning (significance) and, therefore, should not be written down. In<br />

science, only the numbers that have significance (derived from measurement) are written.<br />

Rule 1: Non-zero digits are always significant.<br />

If you measure something and the device you use (ruler, thermometer, triple-beam, balance, etc.)<br />

returns a number to you, then you have made a measurement decision and that ACT of measuring<br />

gives significance to that particular numeral (or digit) in the overall value you obtain.<br />

Hence a number like 46.78 would have four significant figures and 3.94 would have three.<br />

Rule 2: Any zeros between two significant digits are significant.<br />

Suppose you had a number like 409. By the first rule, the 4 and the 9 are significant. However, to<br />

make a measurement decision on the 4 (in the hundred's place) and the 9 (in the one's place), you<br />

HAD to have made a decision on the ten's place. The measurement scale for this number would have<br />

hundreds, tens, and ones marked.<br />

Like the following example:<br />

These are sometimes called "captured zeros."<br />

If a number has a decimal at the end (after the one’s place) then all digits (numbers) are significant<br />

and will be counted.<br />

In the following example the zeros are significant digits and highlighted in blue.<br />

960.<br />

70050.

Rule 3: A final zero or trailing zeros in the decimal portion ONLY are<br />

significant.<br />

This rule causes the most confusion among students.<br />

In the following example the zeros are significant digits and highlighted in blue.<br />

0.07030<br />

0.00800<br />

Here are two more examples where the significant zeros are highlighted in blue.<br />

When Zeros are Not Significant Digits<br />

4.7 0 x 10−³<br />

6.5 0 0 x 10⁴<br />

Zero Type # 1 : Space holding zeros in numbers less than one.<br />

In the following example the zeros are NOT significant digits and highlighted in red.<br />

0.09060<br />

0.00400<br />

These zeros serve only as space holders. They are there to put the decimal point in its correct<br />

location.<br />

They DO NOT involve measurement decisions.<br />

Zero Type # 2 : Trailing zeros in a whole number.<br />

In the following example the zeros are NOT significant digits and highlighted in red.<br />

200<br />

25000<br />

For addition and subtraction, look at the decimal portion (i.e., to the right of the decimal point)<br />

of the numbers ONLY. Here is what to do:<br />

1) Count the number of significant figures in the decimal portion of each number in the problem. (The<br />

digits to the left of the decimal place are not used to determine the number of decimal places in the<br />

final answer.)<br />

2) Add or subtract in the normal fashion.<br />

3) Round the answer to the LEAST number of places in the decimal portion of any number in the<br />

problem<br />

The following rule applies for multiplication and division:<br />

The LEAST number of significant figures in any number of the problem determines the number of<br />

significant figures in the answer.<br />

This means you MUST know how to recognize significant figures in order to use this rule.

How Many Significant Digits for Each Number?<br />

1) 2359 = ______ 4<br />

2) 2.445 x 10−⁵= ______ 4<br />

3) 2.93 x 10⁴= ______ 3<br />

4) 1.30 x 10−⁷= ______ 2<br />

4<br />

5) 2604 = ______<br />

6) 9160 = ______ 4<br />

7) 0.0800 = ______ 2<br />

8) 0.84 = ______ 2<br />

9) 0.0080 = ______ 2<br />

10) 0.00040 = ______ 2<br />

11) 0.0520 = ______<br />

3<br />

12) 0.060 = ______ 2<br />

13) 6.90 x 10−¹= ______ 2<br />

2<br />

14) 7.200 x 10⁵= ______<br />

4<br />

15) 5.566 x 10−²= ______<br />

16) 3.88 x 10⁸= ______<br />

3<br />

17) 3004 = ______ 4<br />

18) 0.021 = ______<br />

3<br />

19) 240 = ______ 3<br />

3<br />

20) 500 = ______

For addition and subtraction, look at the decimal portion (i.e., to the right of the decimal point) of the<br />

numbers ONLY. Here is what to do:<br />

1) Count the number of significant figures in the decimal portion of each number in the problem. (The<br />

digits to the left of the decimal place are not used to determine the number of decimal places in the<br />

final answer.)<br />

2) Add or subtract in the normal fashion.<br />

3) Round the answer to the LEAST number of places in the decimal portion of any number in the<br />

problem.<br />

Solve the Problems and Round Accordingly...<br />

1) 43.287 + 5.79 + 6.284 = ____ 55.36<br />

55<br />

2) 87.54 - 3.3 = _______ 84.2<br />

84<br />

115.3<br />

3) 99.1498 + 6.5397 + 9.7 = _______<br />

115<br />

4) 5.868 - 5.1 = _______ 0.7<br />

1<br />

5) 59.9233 + 86.21 + 99.396 = _______ 245.52<br />

246<br />

6) 7.7 + 26.756 = _______ 34.4<br />

34<br />

7) 66.8 + 2.3 + 4.8516 = _______ 73.9<br />

74<br />

8) 9.7419 + 43.545 = _______<br />

9) 4.8976 + 48.4644 + 1.514 = _______<br />

10) 4.335 + 35.85 = _______<br />

11) 9.448 - 1.7 = _______<br />

12) 75.826 - 8.6555 = _______<br />

13) 57.2 + 23.814 = _______<br />

14) 77.684 - 4.394 = _______<br />

15) 26.4496 + 3.339 = _______<br />

16) 9.6848 + 29.85 = _______<br />

17) 63.11 + 2.5412 + 4.93 = _______<br />

18) 11.2471 + 75.4 = _______<br />

19) 73.745 - 8.755 = _______<br />

20) 6.5238 + 1.7 + 27.79 = _______

The following rule applies for multiplication and division:<br />

The LEAST number of significant figures in any number of the problem determines the number of<br />

significant figures in the answer.<br />

This means you MUST know how to recognize significant figures in order to use this rule.<br />

Solve the Problems and Round Accordingly...<br />

1) 0.6 x 65.0 x 602 = __________<br />

2) 720 ÷ 7.7 = __________<br />

3) 929 x 0.3 = __________<br />

4) 300 ÷ 44.31 = __________<br />

5) 608 ÷ 9.8 = __________<br />

6) 0.06 x 0.079 = __________<br />

7) 0.008 x 72.91 x 7000 = __________<br />

8) 73.94 x 67 x 780 = __________<br />

9) 0.62 x 0.097 x 40 = __________<br />

10) 600 x 10 x 5030 = __________<br />

11) 5200 ÷ 4.46 = __________<br />

12) 0.0052 x 0.4 x 107 = __________<br />

13) 0.099 x 8.8 = __________<br />

14) 0.0095 x 5.2 = __________<br />

15) 8000 ÷ 4.62 = __________<br />

16) 0.6 x 0.8 = __________<br />

17) 2.84 x 0.66 = __________<br />

18) 0.5 x 0.09 = __________<br />

19) 8100 ÷ 34.84 = __________<br />

20) 8.24 x 6.9 x 8100 = __________

Unit 3<br />

Chapter 25 Nuclear Chemistry<br />

The students will learn what happens when an unstable<br />

nucleus decays and how nuclear chemistry affects their lives.<br />

Explore the theory of electromagnetism by comparing and contrasting the<br />

different parts of the electromagnetic spectrum in terms of wavelength,<br />

frequency, and energy, and relate them to phenomena and applications.<br />

Students will be able to compare and contrast the different parts of the<br />

electromagnetic spectrum.<br />

Students will be able to apply knowledge of the EMS to real world phenomena.<br />

Students will be able to quantitatively compare the relationship between energy,<br />

wavelength, and frequency of the EMS.<br />

amplitude<br />

wavelength<br />

frequency<br />

hertz<br />

electromagnetic radiation<br />

photon<br />

Planck’s constant<br />

Explain and compare nuclear reactions (radioactive decay, fission and<br />

fusion), the energy changes associated with them and their associated<br />

safety issues.<br />

Students will be able to compare and contrast fission and fusion reactions.<br />

Students will be able to complete nuclear decay equations to identify the type of<br />

decay.<br />

Students will participate in activities to calculate half-life.<br />

radioactivity<br />

nuclear radiation<br />

alpha particle<br />

beta particle<br />

gamma ray<br />

positron<br />

½ life<br />

transmutation<br />

fission<br />

fusion

Chapter 7<br />

Ionic and Metallic Bonding<br />

The students will learn how ionic compounds form and how<br />

metallic bounding affects the properties of metals.<br />

Compare the magnitude and range of the four fundamental forces<br />

(gravitational, electromagnetic, weak nuclear, strong nuclear).<br />

Students will compare/contrast the characteristics of each fundamental force.<br />

gravity<br />

electromagnetic<br />

strong<br />

weak<br />

Distinguish between bonding forces holding compounds together and other<br />

attractive forces, including hydrogen bonding and van der Waals forces.<br />

Students will be able to compare/contrast traits of ionic and covalent bonds.<br />

Students will be able to compare/contrast basic attractive forces between<br />

molecules.<br />

Students will be able to predict the type of bond or attractive force between<br />

atoms or molecules.<br />

ionic bond<br />

covalent bond<br />

metallic bond<br />

polar covalent bond<br />

hydrogen bond<br />

van der Waals forces<br />

London dispersion forces<br />

Chapter 8<br />

Covalent Bonding<br />

The students will learn how molecular bonding is different<br />

than ionic bonding and electrons affect the shape of a<br />

molecule and its properties.<br />

Interpret formula representations of molecules and compounds in terms of<br />

composition and structure.<br />

Students will be able to interpret chemical formulas in terms of # of atoms.<br />

Students will be able to differentiate between ionic and molecular compounds.<br />

Students will be able to list various VSEPR shapes and identify examples of<br />

each.<br />

Students will be able to predict shapes of various compounds.<br />

Molecule<br />

empirical formula<br />

Atom<br />

Electron<br />

Element<br />

Compound

Learning Goal for this section:<br />

Explain and copare nuclear reactions, radioactive decay, fission, and the<br />

energy, changes associated with them and their associated safety issues.<br />

Notes Section:<br />

Nucleus<br />

N-1amu-none<br />

P-1amu-positve<br />

E-none-negative<br />

carbon 14 could be radioactive because it<br />

had a radioactive isotope.<br />

carbon makes up everything, things have<br />

specific amounts of carbon 14.<br />

Beta particles have the mass of an electron, theres positive and negative beta<br />

particles. Neutrons are both positive and negative, you take away the neutron<br />

it becomes positive<br />

Positive beta-Positron, has<br />

practically no charge.<br />

Can take away positive<br />

charge from neutron and<br />

make a negative, vise<br />

versa.<br />

If you do that is goes down by one EX: poloniom<br />

would become bismouth.<br />

Gamma(small amount)- ENRGY. -Not a huge amount but can be<br />

dangerous<br />

Half life-loses protons, loses power, becomes weaker.<br />

Iodine131 20mg has radioactivity- half life 8 days

The Nucleus<br />

A typical model of the atom is called the Bohr Model, in<br />

honor of Niels Bohr who proposed the structure in 1913. The Bohr atom consists of a central nucleus<br />

composed of neutrons and protons, which is surrounded by electrons which “orbit” around the nucleus.<br />

Protons carry a positive charge of one and have a mass of about 1 atomic mass unit or amu (1 amu =1.7x10-<br />

27 kg, a very, very small number). Neutrons are electrically “neutral” and also have a mass of about 1 amu. In<br />

contrast electron carry a negative charge and have mass of only 0.00055 amu. The number of protons in a<br />

nucleus determines the element of the atom. For example, the number of protons in uranium is 92 and the<br />

number in neon is 10. The proton number is often referred to as Z.<br />

Atoms with different numbers of protons are called elements, and are arranged in the periodic table with<br />

increasing Z.<br />

Atoms in nature are electrically neutral so the number of electrons orbiting the nucleus equals the number of<br />

protons in the nucleus.<br />

Neutrons make up the remaining mass of the nucleus and provide a means to “glue” the protons in place.<br />

Without neutrons, the nucleus would split apart because the positive protons would repel each other. Elements<br />

can have nucleii with different numbers of neutrons in them. For example hydrogen, which normally only has<br />

one proton in the nucleus, can have a neutron added to its nucleus to from deuterium, ir have two neutrons<br />

added to create tritium, which is radioactive. Atoms of the same element which vary in neutron number are<br />

called isotopes. Some elements have many stable isotopes (tin has 10) while others have only one or two. We<br />

express isotopes with the nomenclature Neon-20 or 20 Ne 10, with twenty representing the total number of<br />

neutrons and protons in the atom, often referred to as A, and 10 representing the number of protons (Z).<br />

Alpha Particle<br />

Decay<br />

Alpha decay is a radioactive process in which a<br />

particle with two neutrons and two protons is<br />

ejected from the nucleus of a radioactive atom. The particle is identical to the nucleus of a helium atom.<br />

Alpha decay only occurs in very heavy elements such as uranium, thorium and radium. The nuclei of these<br />

atoms are very “neutron rich” (i.e. have a lot more neutrons in their nucleus than they do protons) which makes<br />

emission of the alpha particle possible.<br />

After an atom ejects an alpha particle, a new parent atom is formed which has two less neutrons and two less<br />

protons. Thus, when uranium-238 (which has a Z of 92) decays by alpha emission, thorium-234 is created<br />

(which has a Z of 90).<br />

Because alpha particles contain two protons, they have a positive charge of two. Further, alpha particles are<br />

very heavy and very energetic compared to other common types of radiation. These characteristics allow alpha<br />

particles to interact readily with materials they encounter, including air, causing many ionizations in a very short<br />

distance. Typical alpha particles will travel no more than a few centimeters in air and are stopped by a sheet of<br />

paper.

Beta Particle Decay<br />

Beta decay is a radioactive process in which an electron is emitted from the nucleus of a radioactive<br />

atom Because this electron is from the nucleus of the atom, it is called a beta particle to distinguish it<br />

from the electrons which orbit the atom.<br />

Like alpha decay, beta decay occurs in isotopes which are “neutron rich” (i.e. have a lot more<br />

neutrons in their nucleus than they do protons). Atoms which undergo beta decay are located below<br />

the line of stable elements on the chart of the nuclides, and are typically produced in nuclear reactors.<br />

When a nucleus ejects a beta particle, one of the neutrons in the nucleus is transformed into a proton.<br />

Since the number of protons in the nucleus has changed, a new daughter atom is formed which has<br />

one less neutron but one more proton than the parent. For example, when rhenium-187 decays<br />

(which has a Z of 75) by beta decay, osmium-187 is created (which has a Z of 76). Beta particles<br />

have a single negative charge and weigh only a small fraction of a neutron or proton. As a result, beta<br />

particles interact less readily with material than alpha particles. Depending on the beta particles<br />

energy (which depends on the radioactive atom), beta particles will travel up to several meters in air,<br />

and are stopped by thin layers of metal or plastic.<br />

Positron emission or beta plus decay (β+ decay) is a subtype of radioactive decay called beta decay,<br />

in which a proton inside a radionuclide nucleus is converted into a neutron while releasing a positron<br />

and an electron neutrino (νe). Positron emission is mediated by the weak force.<br />

An example of positron emission (β+ decay) is shown with magnesium-23 decaying into sodium-23:<br />

23 Mg12 → 23 Na11 + e +<br />

Because positron emission decreases proton number relative to neutron number, positron decay<br />

happens typically in large "proton-rich" radionuclides. Positron decay results in nuclear transmutation,<br />

changing an atom of one chemical element into an atom of an element with an atomic number that is<br />

less by one unit.<br />

Positron emission should not be confused with electron emission or beta minus decay (β− decay),<br />

which occurs when a neutron turns into a proton and the nucleus emits an electron and an<br />

antineutrino.

Gamma<br />

Radiation<br />

After a decay reaction, the nucleus is often in an<br />

“excited” state. This means that the decay has<br />

resulted in producing a nucleus which still has<br />

excess energy to get rid of. Rather than emitting another beta or alpha particle, this energy is lost by<br />

emitting a pulse of electromagnetic radiation called a gamma ray. The gamma ray is identical in<br />

nature to light or microwaves, but of very high energy.<br />

Like all forms of electromagnetic radiation, the gamma ray has no mass and no charge. Gamma rays<br />

interact with material by colliding with the electrons in the shells of atoms. They lose their energy<br />

slowly in material, being able to travel significant distances before stopping. Depending on their initial<br />

energy, gamma rays can travel from 1 to hundreds of meters in air and can easily go right through<br />

people.<br />

It is important to note that most alpha and beta emitters also emit gamma rays as part of their decay<br />

process. However, their is no such thing as a “pure” gamma emitter. Important gamma emitters<br />

including technetium-99m which is used in nuclear medicine, and cesium-137 which is used for<br />

calibration of nuclear instruments.<br />

Half Life<br />

Half-life is the time required for the quantity of a<br />

radioactive material to be reduced to one-half its<br />

original value.<br />

All radionuclides have a particular half-life, some<br />

of which a very long, while other are extremely<br />

short. For example, uranium-238 has such a<br />

long half life, 4.5x109 years, that only a small fraction has decayed since the earth was formed. In<br />

contrast, carbon-11 has a half-life of only 20 minutes. Since this nuclide has medical applications, it<br />

has to be created where it is being used so that enough will be present to conduct medical studies.

The Learning Goal for this assignment is:<br />

Distinguish between bonding forces holding compounds together and other attractive<br />

forces, including hydrogen bonding and Van-Der Waals forces.<br />

Introduction to Ionic Compounds<br />

Those molecules that consist of charged ions with opposite charges are called IONIC. These ionic<br />

compounds are generally solids with high melting points and conduct electrical current. Ionic<br />

compounds are generally formed from metal and a non-metal elements. See Ionic Bonding below.<br />

Ionic Compound Example<br />

For example, you are familiar with the fairly benign unspectacular behavior of common white<br />

crystalline table salt (NaCl). Salt consists of positive sodium ions (Na + ) & negative chloride ions (Cl - ).<br />

On the other hand the element sodium is a silvery gray metal composed of neutral atoms which react<br />

vigorously with water or air. Chlorine as an element is a neutral greenish-yellow, poisonous, diatomic<br />

gas (Cl2).<br />

The main principle to remember is that ions are completely different in physical and chemical<br />

properties from the neutral atoms of the elements.<br />

The notation of the + and - charges on ions is very important as it conveys a definite meaning.<br />

Whereas elements are neutral in charge, IONS have either a positive or negative charge depending<br />

upon whether there is an excess of protons (positive ion) or excess of electrons (negative ion).<br />

Formation of Positive Ions<br />

Metals usually have 1-4 electrons in the outer energy level. The electron arrangement of a rare gas is<br />

most easily achieved by losing the few electrons in the newly started energy level. The number of<br />

electrons lost must bring the electron number "down to" that of a prior rare gas.<br />

How will sodium complete its octet?<br />

First examine the electron arrangement of the atom. The atomic number is eleven, therefore, there<br />

are eleven electrons and eleven protons on the neutral sodium atom. Here is the Bohr diagram and<br />

Lewis symbol for sodium:

This analysis shows that sodium has only one electron in its outer level. The nearest rare gas is neon<br />

with 8 electron in the outer energy level. Therefore, this electron is lost so that there are now eight<br />

electrons in the outer energy level, and the Bohr diagrams and Lewis symbols for sodium ion and<br />

neon are identical. The octet rule is satisfied.<br />

Ion Charge?<br />

What is the charge on sodium ion as a result of losing one electron? A comparison of the atom and<br />

the ion will yield this answer.<br />

Sodium Atom<br />

Sodium Ion<br />

11 p+ to revert to 11 p + Protons are identical in<br />

12 n an octet 12 n<br />

the atom and ion.<br />

Positive charge is<br />

11 e- lose 1 electron 10 e-<br />

caused by lack of<br />

0 charge + 1 charge<br />

electrons.<br />

Formation of Negative Ions<br />

How will fluorine complete its octet?<br />

First examine the electron arrangement of the atom. The atomic number is nine, therefore, there are<br />

nine electrons and nine protons on the neutral fluorine atom. Here is the Bohr diagram and Lewis<br />

symbol for fluorine:<br />

This analysis shows that fluorine already has seven electrons in its outer level. The nearest rare gas<br />

is neon with 8 electron in the outer energy level. Therefore only one additional electron is needed to<br />

complete the octet in the fluorine atom to make the fluoride ion. If the one electron is added, the Bohr<br />

diagrams and Lewis symbols for fluorine and neon are identical. The octet rule is satisfied.

Ion Charge?<br />

What is the charge on fluorine as a result of adding one electron? A comparison of the atom and the<br />

ion will yield this answer.<br />

Fluorine Atom Fluoride Ion *<br />

9 p+ to complete 9 p + Protons are identical in<br />

10 n octet 10 n<br />

9 e- add 1 electron 10 e-<br />

0 charge - 1 charge<br />

the atom and ion.<br />

Negative charge is<br />

caused by excess<br />

electrons<br />

* The "ide" ending in the name signifies a simple negative ion.<br />

Summary Principle of Ionic Compounds<br />

An ionic compound is formed by the complete transfer of electrons from a metal to a nonmetal and<br />

the resulting ions have achieved an octet. The protons do not change. Metal atoms in Groups 1-3<br />

lose electrons to non-metal atoms with 5-7 electrons missing in the outer level. Non-metals gain 1-4<br />

electrons to complete an octet.<br />

Octet Rule<br />

Elemental atoms generally lose, gain, or share electrons with other atoms in order to achieve the<br />

same electron structure as the nearest rare gas with eight electrons in the outer level.<br />

The proper application of the Octet Rule provides valuable assistance in predicting and explaining<br />

various aspects of chemical formulas.<br />

Introduction to Ionic Bonding<br />

Ionic bonding is best treated using a simple<br />

electrostatic model. The electrostatic model<br />

is simply an application of the charge<br />

principles that opposite charges attract and<br />

similar charges repel. An ionic compound<br />

results from the interaction of a positive and<br />

negative ion, such as sodium and chloride in<br />

common salt.<br />

The IONIC BOND results as a balance<br />

between the force of attraction between<br />

opposite plus and minus charges of the ions<br />

and the force of repulsion between similar<br />

negative charges in the electron clouds. In<br />

crystalline compounds this net balance of<br />

forces is called the LATTICE ENERGY.<br />

Lattice energy is the energy released in the<br />

formation of an ionic compound.<br />

DEFINITION: The formation of an IONIC<br />

BOND is the result of the transfer of one or<br />

more electrons from a metal onto a nonmetal.

Metals, with only a few electrons in the outer energy level, tend to lose electrons most readily. The<br />

energy required to remove an electron from a neutral atom is called the IONIZATION POTENTIAL.<br />

Energy + Metal Atom ---> Metal (+) ion + e-<br />

Non-metals, which lack only one or two electrons in the outer energy level have little tendency to lose<br />

electrons - the ionization potential would be very high. Instead non-metals have a tendency to gain<br />

electrons. The ELECTRON AFFINITY is the energy given off by an atom when it gains electrons.<br />

Non-metal Atom + e- --- Non-metal (-) ion + energy<br />

The energy required to produce positive ions (ionization potential) is roughly balanced by the energy<br />

given off to produce negative ions (electron affinity). The energy released by the net force of<br />

attraction by the ions provides the overall stabilizing energy of the compound.<br />

Notes Section:<br />

Non metal with metal bond is ionic, non metal with non metal is covalent bond.<br />

gives off an electroneasier<br />

to loose electrons than to gain.<br />

Ionic compound diagram<br />

..<br />

Mg:S:<br />

**<br />

could also add more of the elements, Be P Be P Be and this would be eaven.

The Learning Goal for this assignment is:<br />

Distinguish between bonding forces holding compounds togather and other<br />

attractive forces, including hydrogen bonding and van der waals forces.<br />

Introduction to Covalent Bonding:<br />

Bonding between non-metals consists of two electrons shared between two atoms. Using the Wave<br />

Theory, the covalent bond involves an overlap of the electron clouds from each atom. The electrons<br />

are concentrated in the region between the two atoms. In covalent bonding, the two electrons shared<br />

by the atoms are attracted to the nucleus of both atoms. Neither atom completely loses or gains<br />

electrons as in ionic bonding.<br />

There are two types of covalent bonding:<br />

1. Non-polar bonding with an equal sharing of electrons.<br />

2. Polar bonding with an unequal sharing of electrons. The number of shared electrons depends on<br />

the number of electrons needed to complete the octet.<br />

NON-POLAR BONDING results when two identical non-metals equally share electrons between<br />

them. One well known exception to the identical atom rule is the combination of carbon and hydrogen<br />

in all organic compounds.<br />

Hydrogen<br />

The simplest non-polar covalent molecule is hydrogen. Each hydrogen<br />

atom has one electron and needs two to complete its first energy level.<br />

Since both hydrogen atoms are identical, neither atom will be able to<br />

dominate in the control of the electrons. The electrons are therefore<br />

shared equally. The hydrogen covalent bond can be represented in a<br />

variety of ways as shown here:<br />

The "octet" for hydrogen is only 2 electrons since the nearest rare gas is<br />

He. The diatomic molecule is formed because individual hydrogen atoms<br />

containing only a single electron are unstable. Since both atoms are<br />

identical a complete transfer of electrons as in ionic bonding is<br />

impossible.<br />

Instead the two hydrogen atoms SHARE both electrons equally.<br />

Oxygen<br />

Molecules of oxygen, present in about 20% concentration in air are<br />

also covalent molecules. See the graphic on the left of the Lewis Dot<br />

Structure.<br />

There are 6 electrons in the outer shell, therefore, 2 electrons are<br />

needed to complete the octet. The two oxygen atoms share a total of<br />

four electrons in two separate bonds, called double bonds.<br />

The two oxygen atoms equally share the four electrons.

POLAR BONDING results when two different non-metals unequally share electrons between them.<br />

One well known exception to the identical atom rule is the combination of carbon and hydrogen in all<br />

organic compounds.<br />

The non-metal closer to fluorine in the Periodic Table has a greater tendency to keep its own electron<br />

and also draw away the other atom's electron. It is NOT completely successful. As a result, only<br />

partial charges are established. One atom becomes partially positive since it has lost control of its<br />

electron some of the time. The other atom becomes partially negative since it gains electron some of<br />

the time.<br />

Hydrogen Chloride<br />

Hydrogen Chloride forms a polar covalent molecule. The graphic<br />

on the left shows that chlorine has 7 electrons in the outer shell.<br />

Hydrogen has one electron in its outer energy shell. Since 8<br />

electrons are needed for an octet, they share the electrons.<br />

However, chlorine gets an unequal share of the two electrons,<br />

although the electrons are still shared (not transferred as in ionic<br />

bonding), the sharing is unequal. The electrons spends more of the<br />

time closer to chlorine. As a result, the chlorine acquires a "partial"<br />

negative charge. At the same time, since hydrogen loses the<br />

electron most - but not all of the time, it acquires a "partial" charge.<br />

The partial charge is denoted with a small Greek symbol for delta.<br />

Water<br />

Water, the most universal compound on all of the earth, has the property of<br />

being a polar molecule. As a result of this property, the physical and<br />

chemical properties of the compound are fairly unique.<br />

Dihydrogen Oxide or water forms a polar covalent molecule. The graphic on<br />

the left shows that oxygen has 6 electrons in the outer shell. Hydrogen has<br />

one electron in its outer energy shell. Since 8 electrons are needed for an<br />

octet, they share the electrons.<br />

Notes Section:<br />

when it all equals zero than its good and you gucci.... add the elctrons to the terminal<br />

stuff.....

C 2 H 6 O Ethanol CH 3 CH 2 O<br />

Step 1<br />

Find valence e- for all atoms. Add them together.<br />

C: 4 x 2 = 8<br />

H: 1 x 6 = 6<br />

O: 6<br />

Total = 20<br />

Step 2<br />

Find octet e- for each atom and add them together.<br />

C: 8 x 2 = 16<br />

H: 2 x 6 = 12<br />

O: 8<br />

Total = 36<br />

Step 3<br />

Subtract Step 1 total from Step 2.<br />

Gives you bonding e-.<br />

36 – 20 = 16e-<br />

Step 4<br />

Find number of bonds by diving the number in step 3 by 2<br />

(because each bond is made of 2 e-)<br />

16e- / 2 = 8 bond pairs<br />

These can be single, double or triple bonds.<br />

Step 5<br />

Determine which is the central atom<br />

Find the one that is the least electronegative.<br />

Use the periodic table and find the one farthest<br />

away from Fluorine or<br />

The one that only has 1 atom.

Step 6<br />

Put the atoms in the structure that you think it will<br />

have and bond them together.<br />

Put Single bonds between atoms.<br />

Step 7<br />

Find the number of nonbonding (lone pairs) e-.<br />

Subtract step 3 number from step 1.<br />

20 – 16 = 4e- = 2 lone pairs<br />

Step 8<br />

Complete the Octet Rule by adding the lone<br />

pairs.<br />

Then, if needed, use any lone pairs to make<br />

double and triple bonds so that all atoms meet<br />

the Octet Rule.<br />

See Step 4 for total number of bonds.

Linear<br />

Molecular Geometry<br />

Orbital Equation Lone Pairs Angle<br />

sp AX 2 0 180<br />

BeCl 2<br />

Cl<br />

Be<br />

Cl<br />

Beryllium dichloride<br />

element bond lone pair<br />

C

Trigonal Planar<br />

Molecular Geometry<br />

Orbital Equation Lone Pairs Angle<br />

sp 2 Ax 3 None 120<br />

BF 3<br />

F<br />

Boron trifluoride<br />

B<br />

F<br />

F<br />

element bond lone pair<br />

C

Bent<br />

Molecular Geometry<br />

Orbital Equation Lone Pairs Angle<br />

SP 2 Ax2E 1 116<br />

O 3<br />

O<br />

O<br />

O<br />

Trioxide<br />

element bond lone pair<br />

C

Tetrahedral<br />

Molecular Geometry<br />

Orbital Equation Lone Pairs Angle<br />

SP 3 AX 4 0 109.5<br />

Phosphate<br />

PO 4<br />

3-<br />

O<br />

O<br />

P<br />

O<br />

O<br />

element bond lone pair<br />

C

Trigonal Pyramidal<br />

Molecular Geometry<br />

Orbital Equation Lone Pairs Angle<br />

Sp 3 AX 3 E 1 107<br />

PH 3<br />

H<br />

P<br />

H<br />

H<br />

Phosphorus trihybrid<br />

element bond lone pair<br />

C

Bent<br />

Molecular Geometry<br />

Orbital Equation Lone Pairs Angle<br />

SP 3 AX 2 E 2 2 104.5<br />

H 2 O<br />

H<br />

O<br />

H<br />

Dihydrogen oxide<br />

element bond lone pair<br />

C

Trigonal Bipyramid<br />

Molecular Geometry<br />

Orbital Equation Lone Pairs Angle<br />

SP 3 d AX 5 none 120/90<br />

PCl 5<br />

Cl<br />

Cl<br />

P<br />

Phosphorus pentacloride<br />

Cl<br />

Cl<br />

Cl<br />

element bond lone pair<br />

C

T-shaped<br />

Molecular Geometry<br />

Orbital Equation Lone Pairs Angle<br />

sp 3 d AX 3 E 2 2 90<br />

ClF 3<br />

Chlorine trifloride<br />

F<br />

C<br />

F<br />

F<br />

element bond lone pair<br />

C

Octahedral<br />

Molecular Geometry<br />

Orbital Equation Lone Pairs Angle<br />

sp 3 d 2 AX 6 none 90<br />

Sulfur hexafluoride<br />

SF 6<br />

F<br />

F<br />

F<br />

s<br />

F<br />

F<br />

F<br />

element bond lone pair<br />

C

Square Planar<br />

Molecular Geometry<br />

Orbital Equation Lone Pairs Angle<br />

Sp 3 d 2 Ax 4 E 2 2 90<br />

Iodine tetrachloride<br />

ICl 4<br />

-<br />

Cl<br />

Cl<br />

I<br />

Cl<br />

Cl<br />

element bond lon<br />

C

Orbitals Equation Lone Pairs Angle<br />

Name<br />

sp AX 2 0 180 Beryllium dichloride<br />

sp2 AX3 None 120 Boron trifluoride<br />

SP2 Ax2E 1 116 Trioxide<br />

SP3<br />

Ax 4 0 109.5 Phosphate<br />

Sp3 Ax3E 1 107 Phosphorus trihybrid<br />

SP3 Ax2E 2 2 104.5 Dihydrogen oxide<br />

SP3d Ax5 none 120/90 Phosphorus pentacloride<br />

sp3d Ax3E2 2 90 Phosphorus pentacloride<br />

sp3d2 Ax6 none 90 Sulfur hexafluoride<br />

Sp3d2 Ax4E2 2 90 Iodine tetrachloride

Name Formula Charge<br />

Dichromate Cr₂O₇ 2-<br />

Sulfate SO₄ 2-<br />

Hydrogen Carbonate HCO₃ 1-<br />

Hypochlorite ClO 1-<br />

Phosphate PO₄ 3-<br />

Nitrite NO₂ 1-<br />

Chlorite ClO₂ 1-<br />

Dihydrogen phosphate H₂PO₄ 1-<br />

Chromate CrO₄ 2-<br />

Carbonate CO₃ 2-<br />

Hydroxide OH 1-<br />

Hydrogen phosphate HPO₄ 2-<br />

Ammonium NH₄ 1+<br />

Acetate C₂H₃O₂ 1-<br />

Perchlorate ClO₄ 1-<br />

Permanganate MnO₄ 1-<br />

Chlorate ClO₃ 1-<br />

Hydrogen Sulfate HSO₄ 1-<br />

Phosphite PO₃ 3-<br />

Sulfite SO₃ 2-<br />

Silicate SiO₃ 2-<br />

Nitrate NO₃ 1-<br />

Hydrogen Sulfite HSO₃ 1-<br />

Oxalate C₂O₄ 2-<br />

Cyanide CN 1-<br />

Hydronium H₃O 1+<br />

Thiosulfate S₂O₃ 2-

Chapter 9<br />

Unit 4<br />

Chemical Names and Formulas<br />

The students will learn how the periodic table helps them<br />

determine the names and formulas of ions and compounds.<br />

Chapter 22 Hydrocarbon Compounds<br />

The student will learn how Hydrocarbons are named and the<br />

general properties of Hydrocarbons.<br />

Describe how different natural resources are produced and how their rates<br />

of use and renewal limit availability.<br />

Students will explore local, national, and global renewable and nonrenewable<br />

resources.<br />

Students will explain the environmental costs of the use of renewable and<br />

nonrenewable resources.<br />

Students will explain the benefits of renewable and nonrenewable resources.<br />

Nuclear reactors<br />

Natural gas<br />

Petroleum<br />

Refining<br />

Coal

Chapter 23 Functional Groups<br />