You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

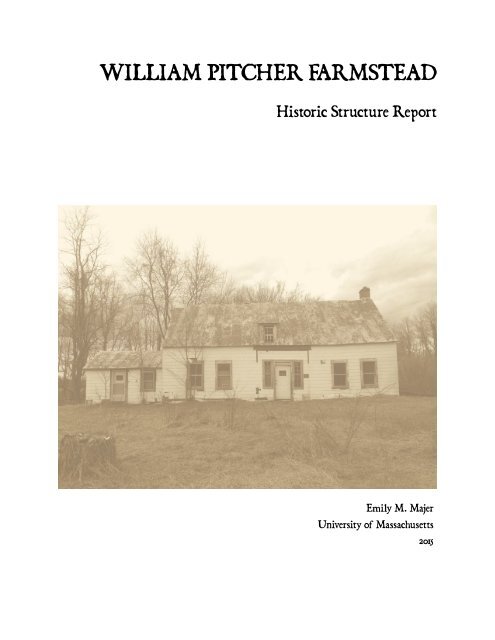

WILLIAM PITCHER FARMSTEAD<br />

Historic Structure Report<br />

Emily M. Majer<br />

University of Massachusetts<br />

2015

CONTENTS<br />

____________________________________________________________________________<br />

INTRODUCTION<br />

HISTORY<br />

The Schuyler Patent and the Palatines 3<br />

The <strong>Pitcher</strong>s, Generations I-III 9<br />

The <strong>Pitcher</strong>s, Generations IV-VII 13<br />

The Last 73 Years 19<br />

DESCRIPTIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS<br />

The Site 20<br />

The House<br />

Exterior 22<br />

Recommendations 31<br />

Interior 32<br />

Recommendations 97<br />

Green Renovation Recommendations 98<br />

APPENDICES<br />

I<br />

II<br />

III<br />

IV<br />

V<br />

VI<br />

VII<br />

VIII<br />

BIBLIOGRAPHY<br />

Deed Chronology and Maps<br />

<strong>Pitcher</strong> Genealogy<br />

<strong>Pitcher</strong> Population Schedule<br />

Drawings<br />

Existing 2004<br />

Structural Evolution<br />

Masonry Analysis<br />

Wood Analysis<br />

Finishes Analysis<br />

Wallpaper Samples

INTRODUCTION<br />

____________________________________________________________________________<br />

The <strong>William</strong> <strong>Pitcher</strong> farmhouse is located near the hamlet of Upper Red Hook, New York<br />

and was likely built between 1725 and 1746, but certainly prior to 1768. On May 25<br />

of that year, the property was deeded to <strong>William</strong> <strong>Pitcher</strong> by his father and referred to<br />

as “the farm now in the possession of the said <strong>William</strong> Bitcher(sic).” 1 It is an important<br />

domestic building for the fact that is one of the oldest surviving examples of timberframed<br />

Dutch/German vernacular architecture in the area. The house is set back 250<br />

yards from the north side of <strong>Pitcher</strong> Lane, a quiet east-west road, a mile and a half long<br />

connecting Route 9, known prior to 1776 as the King’s Highway, to County Route 79,<br />

formerly referred to as the road to Red Hook Landing.<br />

Members of the <strong>Pitcher</strong> family lived in the house continuously until the later years of<br />

the 19th century. After that it became an incidental structure. The farmhouse<br />

remained in the family, likely a lodging for seasonal workers on the large fruit farm,<br />

until 1942. The larger farm property was sold seven times in the second half of the<br />

20th century, becoming a dairy enterprise by the 1970s. The <strong>William</strong> <strong>Pitcher</strong> house<br />

was intermittently occupied, most recently by the herdsman of Linden Farms and his<br />

family. Since 2000, the farmhouse has been vacant, home to raccoons and occasional<br />

vandals. The roof, which is at least 100 years old, has kept the weather out, but there<br />

are some failures in the building envelope.<br />

1<br />

Dutchess County Clerk’s Office, Poughkeepsie, New York

This historic structure report is intended to document the farmhouse, should it prove<br />

to be beyond repair; or to serve as an owner’s manual to assist in restoration, should<br />

the current owner choose such an undertaking.<br />

The information in this report was collected and assembled between February 2014<br />

and April 2015 in fulfillment of the capstone project requirement for the University of<br />

Massachusetts Master of Science in Historic Preservation program. The process has<br />

involved investigation of deeds, wills, and church records; census and agricultural<br />

schedules; newspapers, maps, and tax rolls; structural assessment and analysis of<br />

bricks, mortar, wood, plaster, finishes, and coverings. It has also involved vagrant and<br />

large animal exclusion. Additional information about this building will certainly be<br />

uncovered through future physical exploration and further sleuthing through human and<br />

institutional repositories.<br />

The <strong>William</strong> <strong>Pitcher</strong> <strong>Farmstead</strong> is historically significant for its association with early<br />

settlement, architectural patterns, and economic development of this area of the<br />

Hudson Valley. The amount of local interest that this project has generated to date<br />

bespeaks an enthusiasm that has been encouraging.<br />

2

HISTORY<br />

THE SCHUYLER PATENT AND THE PALATINES 1688-1725<br />

The primary interest of the Dutch in New Netherland was the collection of beaver pelts.<br />

As such they had established nearly evenly spaced trading posts along Hudson’s River<br />

at New Amsterdam (Manhattan), Wiltwyck (Kingston), and Beverwyck (Albany), but<br />

the rest of the colony was essentially a howling wilderness. The Treaty of Breda, which<br />

ended the Anglo-Dutch War, confirmed the blood-less conquest of New Netherland by<br />

the English on July 21, 1667. Colonial Governor Thomas Dongan was tasked with<br />

settling the land between Manhattan and Albany in order to generate revenue, as well<br />

2<br />

as to secure the Crown’s claim to it. To that end, he granted patents of large tracts of<br />

land to entrepreneurial and well-connected men of means, and turned over to them the<br />

responsibility for populating and clearing the land, hoping that self-interest and the<br />

promise of profit would provide adequate motivation.<br />

Pieter Schuyler, the first mayor of Albany, having first purchased land from the natives,<br />

was granted a patent to it by Governor Dongan on June 2, 1688. This patent was<br />

confirmed and recorded in 1704. The 22,400 acres was thus described,<br />

“Situate, lying and being on the east side of Hudson’s River in Dutchess County, over<br />

against Magdalene Island, beginning at a certain creek called Metambesem, thence running<br />

easterly to the southmost part of a certain meadow called Tanquashqueick, and from that<br />

meadow easterly to a certain small lake or pond called Waraughkameek; from thence northerly<br />

so far till upon a due east and west line it reaches over against the Sawyer’s creek, from thence<br />

2 “Colonial Land Grants in Dutchess County, N.Y. A Case Study in Settlement,” <strong>William</strong> P.<br />

McDermott, The Hudson Valley Regional Review, September 1986, Volume 3, Number 2<br />

3

due west to the Hudson’s river aforesaid, and from thence southerly along the said river to the<br />

said creek called Metambesem” 3<br />

The Schuyler patent was bounded to the north by the Livingston Manor, 160,000 acres<br />

awarded to Robert Livingston in 1686; by the Little Nine Partners patent to the east;<br />

Dutchman Henry Beekman’s Rhinebeck patent on the south; and the Hudson River<br />

along the western edge (MAP 1).<br />

Although a patent for Kipsburgh Manor, the present hamlet of Rhinecliff in the town of<br />

Rhinebeck, had been granted to Kingston Dutchmen Adrian Roosa, Jan Elting, and<br />

Hendrick and Jacobus Kip by Governor Dongan June 2, 1688, on account of Henry<br />

Beekman’s considerable influence and enthusiasm for development, the Kipsburgh<br />

patent was subsumed by Beekman’s Rhinebeck patent, which was confirmed by<br />

Governor Cornbury in 1703.<br />

In 1689 Peter Schuyler sold approximately one half of the north quarter of his patent<br />

bordering Livingston Manor to Harme Van Gansevoort, an Albany brewer, who<br />

transferred the land in 1704 to Harme Janse Knickerbacker. In 1722 Peter Schuyler<br />

had the north quarter of his patent surveyed and divided into 13 lots; seven were<br />

granted to the Knickerbacker heirs, the other six were sold to Captain Nicholas<br />

Hoffman of Kingston. The remaining three-quarters of Schuyler’s patent had already<br />

been divided into six lots of approximately 3,000 acres each and sold in pairs as<br />

4<br />

described in a deed dated February 11, 1717/18. The southern pair, bordering Henry<br />

Beekman’s patent, were sold to Tierck DeWitt of Ulster County; Joachem Staats of<br />

Rensselaerwyck and Barent Van Benthuysen of Dutchess County bought two lots each<br />

3 Documentary History of Rhinebeck, Edward M. Smith, Rhinebeck, Dutchess County, NY, 1881<br />

p.22<br />

4<br />

History of Dutchess County, James H. Smith, D. Mason & Co., Syracuse, NY, 1882, p.173<br />

4

5<br />

(MAP 3). By 1725, Tierk DeWitt had sold his lots to Henry Beekman, and the heirs of<br />

Staats sold their land to Barent Van Benthuysen and his sons: Pieter, Jacob, Abraham,<br />

6<br />

and Gerrit; and his nephew Andries Heremanse(sic)(MAP 5).<br />

The Van Benthuysen and Heermanse families, who moved across the Hudson from<br />

Kingston, were related by marriage. Three Van Wagenen sisters: Jannetje, Annatjen<br />

and Neeltje, daughters of Gerrit Aartsen, one of the original patentees of Rhinebeck,<br />

married Barent Van Benthuysen, and brothers Hendricus and Andries Heermanse<br />

respectively. Jannetje and Barent Van Benthuysen married in Kingston in 1701 and<br />

had Gerrit, Jan, Catryntje, Anna, Peter, Jacob, and Abraham between 1702 and 1718.<br />

Annatjen and Hendricus Heermanse settled in Rhinebeck to raise their six children on<br />

land that would become “Ellerslie,” the estate of Levi P. Morton. Neeltje and Andries<br />

Heermanse had fourteen children between 1711 and 1737: Jan, Engeltie, Jacob,<br />

Annatje, Janneka, Clara, Gerrit, Petrus, Hendricus, Catrina, Wilhelmus, Nicholas, Phillipus,<br />

7<br />

and Abraham. The Van Benthuysens and Heermanses, along with the Hoffmans and<br />

Vosburgs, who also moved from Kingston around the same time, intermarried and<br />

populated their purchase.<br />

In the census of 1714, there were 67 heads of households, 445 residents total,<br />

including 29 slaves, recorded in what was then Dutchess County; from the north line of<br />

Westchester County to the Roelof-Jansen Kill (creek) in what is now Columbia County.<br />

By the first tax assessment in 1723, there were 97 households in the North Ward alone<br />

8<br />

(MAP 2).<br />

5 referenced in a deed dated April 3, 1720 between heirs of Barent Staats and Pieter, Jacob,<br />

and Abraham Van Benthuysen, recorded November 27, 1744<br />

6 Dutchess County Clerk’s Office, Liber 10: 137, April 1, 1747 between Pieter, Jacob, Abraham,<br />

and Barent Van Benthuysen along with Andries Heremanse; and Gerrit Van Benthuysen<br />

7<br />

8<br />

Documentary History of Rhinebeck, E.M. Smith, Rhinebeck, New York, 1881, p.35<br />

Historic Old Rhinebeck, Howard H. Morse, Pontico Printery, Tarrytown, New York, 1908, p.421<br />

5

This population increase was due in large part to the arrival in 1710 of an indentured<br />

workforce from the Palatinate region of southwestern Germany, sent to New York by<br />

Queen Anne at the invitation of Robert Livingston. This group, referred to as “the<br />

Palatines” or “the Poor Palatines,” had left their homes in the Rhine Valley en masse as<br />

conditions deteriorated. French troops, engaged in the War of Spanish Succession,<br />

went wilding through the southwest in 1706. The brutal winter of 1708 and the<br />

instability of living in an area of tiny, ill-managed principalities made for a restive<br />

population. In 1706 a Lutheran minister from Wurttemberg named Joshua Kocherthal<br />

wrote a promotional pamphlet called A Complete and Detailed Report of the Renowned<br />

District of Carolina Located in English America. In 1708 Kocherthal and fifty followers<br />

went to London where they secured passage to the colonies by claiming to be victims<br />

of attacks by the French. This successful gambit, although they had been taken to New<br />

York rather than Carolina, encouraged Kocherthal to return to the Palatinate and try<br />

again. Kocherthal enhanced his pamphlet with even more glowing descriptions of the<br />

colonies, so much so that it was referred to as “The Golden Book,” exciting such<br />

9<br />

interest that three new editions were printed in 1709. Kocherthal’s pamphlet implied<br />

that Queen Anne was eager to have her colonies settled and would be happy to provide<br />

passage to anyone willing to go. This unsupported claim caused a stampede of 13,000<br />

souls to London, where encampments were hastily set up at Camberwell and<br />

Blackheath. Public sentiment turned against the immigrants as their numbers<br />

increased. In December 1709 Robert Hunter, the recently appointed Governor of New<br />

York, proposed a plan that would both benefit the Crown and remove the Palatines<br />

from London.<br />

The British Navy relied on trade with Sweden for “naval stores”(tar and pitch) that<br />

were necessary for waterproofing the ropes and sealing the hulls of ships. For financial<br />

and security reasons, this was not an ideal situation. Hunter suggested that the<br />

9 Becoming German: The 1709 Palatine Migration to New York, Philip Otterness, Cornell<br />

University Press, Ithaca and London, 2006, p.27<br />

6

Palatines could be settled in New York along the Hudson River and would serve the dual<br />

purpose of producing naval stores from the forests there AND their presence would<br />

serve as a deterrent against the French. Hunter’s plan was that the Palatines would<br />

repay the Queen for the cost of their transport and early settlement from the profit<br />

from this enterprise, and, once their debts were repaid, each person would be granted<br />

40 acres of land.<br />

Three thousand Palatines set sail for New York in April 1710, 4,000 were given<br />

passage back to Rotterdam, a few hundred remained in London, and the rest dispersed<br />

to Ireland and Jamaica. Due to casualties in transit, 2,200 Palatines arrived in New<br />

10<br />

York City, which at the time had only 6,000 inhabitants.<br />

During their long journey from their homes, the Palatines had become a tight group.<br />

Adversity had broken down regional, religious, and material differences. Losing such a<br />

large portion of their number on the voyage had left many adults single and many<br />

children orphans. Since Hunter’s plan had a narrow profit margin to begin with, he was<br />

not inclined to provide for those who would not be contributing to the naval stores<br />

project. He arranged for orphans and children of widows to be apprenticed out as<br />

11<br />

young as three or four. The remarriage rate among the Palatines was high due to the<br />

importance of each member of the nuclear family for the survival of the group. This<br />

intermarriage further cemented the bonds among the group, who were also bound by<br />

their dissatisfaction with the naval stores enterprise. The average age of the Palatines<br />

was 35. They had left their homeland on the promise of freedom from serfdom in the<br />

bloated duchies of petty princes. They wanted to be farmers, not to live as servants,<br />

dependent upon the whims and wishes of others.<br />

10<br />

11<br />

Otterness, p.81<br />

Otterness, p.81<br />

7

In September 1710, Governor Hunter purchased 6,000 acres of land on the Hudson<br />

River, 100 miles north of New York City, within the manor of Robert Livingston. The<br />

trees from which the Palatines would be deriving the naval stores were a few miles<br />

inland, also on Livingston’s land. This arrangement had many benefits for Livingston:<br />

the Palatines would be clearing and improving his land, which had been previously<br />

unsettled; Livingston would have right to all trees cut down; and he was given the<br />

contract to provide the Palatines with bread and beer. Three camps were established<br />

on the west side of the Hudson and four situated on the east side, south of the Roelof-<br />

Jansen Kill: Haysbury, named for Hunter’s wife, Lady Hay; Queensbury and Annsbury,<br />

both named for Queen Ann; and Hunterstown.<br />

While the Palatines’ resentment was growing, Governor Hunter was running into trouble<br />

from England. The naval stores project was far from reducing the British navy’s<br />

dependence on Sweden, having not produced even one barrel of tar. Parliament<br />

refused to reimburse Hunter for the money he had put out for the support of the<br />

Palatines. In early September of 1712, the naval stores endeavor was shut down and<br />

the Palatine project was abandoned.<br />

Aside from his early arrangement with Harme Van Gansevoort, Pieter Schuyler appears<br />

to have been content to let the rest of his patent languish. In contrast, Henry<br />

Beekman was eager to get his land settled and actively encouraged the families of<br />

12<br />

disenfranchised German immigrants to rent or purchase farms from him. Culturally,<br />

the Dutch and the Palatines were quite similar, having come from an area sharing a<br />

border. Thirty-five Palatine families took Beekman up on his offer and moved to<br />

Monterey, renaming the larger area Rhine (for their homeland) beck (as a nod to<br />

Beekman). A union church, which served both Lutheran and Dutch Reformed<br />

congregations, was established in 1716. Lutheran minister and author of “The Golden<br />

12 Frank Hasbrouck ed., The History of Dutchess County New York, Chap. XXIX, S.A. Matthiew,<br />

Poughkeepsie, NY, 1909<br />

8

Book,” Joshua Kocherthal, who had sailed from London with the Palatines and<br />

ministered to them at the camps, shared the pulpit with pastor Johann Fredrick Haeger,<br />

who had served the Reformed congregation. The Lutherans and the Dutch Reformed<br />

congregations shared the church until 1723, when the Lutherans built a stone church,<br />

St. Peter’s, approximately half a mile north on the Post Road.<br />

As of 1718, there were still 91 Palatine families, 359 people living on the east camp<br />

land in what had become known as Germantown. Apparently they were holding out for<br />

title to the land that had been promised them by Queen Anne. In 1724 Palatine<br />

settlers Jacob Sharpe and Christopher Hagadorn petitioned the Provincial Council on<br />

behalf of the 63 families that had been willing to remain, to be granted title to the<br />

land. Cadwallader Colden, the Surveyor-General at the time, supported this petition and<br />

the patent was granted on August 26, 1724. 13<br />

THE PITCHERS, GENERATIONS I-III<br />

Johannes Hermann Betzer (alternately written as Bitzer, Pitsier, Pitzer, and finally<br />

<strong>Pitcher</strong>) and his wife, Elsen Maria Franz, were born in Hachenburg, in the Rhineland-<br />

Palatinate region. They were 40 and 43 respectively when they arrived in New York in<br />

July 1710 with their seven children. Arriving on the eighth of Governor Hunter’s ten<br />

ships, the Betzers were settled at Annsbury, the most northern of the east camps,<br />

located on the Hudson River at what is now considered North Germantown. Johannes<br />

Betzer was among those who volunteered to join the Walker Expedition to Quebec in<br />

14<br />

1711 to fight in “Queen Anne’s War.” As of 1717, Johannes Hermann and Elsen<br />

13 History of Columbia County, New York, Captain Franklin Ellis, Everts and Ensign,<br />

Philadelphia, 1878<br />

14 Documentary History of New York,Vol.III, E.B. O’Callahan, Weed, Parsons & Co. Public<br />

Printers, Albany, New York, 1850, p. 571-572<br />

9

15<br />

Maria were still living in Annsbury with two of their children. In 1724 he was among<br />

the signers of the petition submitted to the Provincial Council as being willing to stay if<br />

land were finally granted.<br />

Johannes and Elsen Maria had three sons: Peter, born 1697; Adam, born 1702; and<br />

Johan Theiss, born 1708. Apparently Johann Theiss was the first of them to move<br />

16<br />

south. Early tax records for Rhinebeck place him there in 1732. In 1740, Cadwallader<br />

Colden surveyed the land that had been granted to the Palatines as a result of their<br />

petition in 1724; the resulting map shows Adam and Peter <strong>Pitcher</strong> each owning two<br />

17<br />

parcels of land (MAP 4). Perhaps they had inherited this land from their father. Adam<br />

<strong>Pitcher</strong> held onto his Germantown land and purchased 123 acres from Nicholas<br />

Hoffman in the north portion of the Schuyler patent in 1746 where he established his<br />

homestead farm. He also acquired land in the Little Nine Partners patent; in 1747 he<br />

bought 2/3 of small Lot 8 from the Van Benthuysens and Andries Heermanse, just east<br />

of small Lot 7, which Peter <strong>Pitcher</strong> had purchased the year before.<br />

On March 17, 1746 Peter <strong>Pitcher</strong>, age 49, purchased Lot 7 from the Van<br />

Benthuysens and Andries Heermanse for the sum of 550 pounds current money of the<br />

province of New York “together with all and singular the houses barnes buildings lands<br />

meadows pastures commons feedings trees woods underwoods profits advantages and<br />

with all the appurtenances to the said lott number seven.” 18<br />

Peter <strong>Pitcher</strong>’s neighbor to the west, on Lot 6, was Andries Heermanse himself. It is<br />

possible that, since reference is made to existing structures “houses” and “barnes” in<br />

15 “Ulrich Simmendinger Register, 1717”, http://immigrantships.net/v4/1700v4/<br />

simmendinger17100100A_L.html, also at New York Public Library Rare Books Room<br />

16 Dutchess County New York Tax Lists 1718-1787, Clifford M. Buck, Kinship (Press),<br />

Rhinebeck, New York, 1991<br />

17<br />

18<br />

see Colden map<br />

Dutchess County Clerk’s Office, Deeds; Liber 2 Page 349, 17 March 1746<br />

10

the deed, Peter and his family had already been living on the property as tenants<br />

before the purchase, and that more than one house was on the property prior to 1746.<br />

The Heermanse homestead farm, located in the northeast quadrant of that parcel is<br />

listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It is noted for being a rare example of<br />

an 18th-century (circa 1733 or 1745) stone farmhouse. The Heermanse farm is on a<br />

road that connected the King’s Highway (now Route 9) to the Hudson River at<br />

Hoffman’s Landing, which was subsequently known as Cantine’s Landing, Upper Red<br />

Hook Landing, and now is called Tivoli. In 1749, Pieter Pitser (sic) is listed as having<br />

been the overseer of the road to “Hoffman’s Landing,” which is now County Route 78<br />

(Kerley’s Corners Road). 19 This information places the original <strong>Pitcher</strong> farm to the east<br />

of the Heermance Farm, near the intersection with the King’s Highway (MAP 6). In<br />

1719, Peter <strong>Pitcher</strong> married Anna Catherine Phillips and they had Maria Catherine,<br />

Wilhelm, Magdalena, Gertraudt, Christina, Elizabeth, and Adam between 1720 and<br />

1738. Wilhelm was baptised at the union church in Rhinebeck in 1725. 20<br />

At the age of 71 on 13 May 1768, Peter Pitser (sic) divided his property in half, north<br />

and south (MAP 7). He deeded his own dwelling house and 275 acres to his younger son<br />

Adam. Two weeks later Adam, only 30 years old but “weak in body but of sound and<br />

perfect mind,” willed all his property to his wife, Anna Maria Richter, but gave his father<br />

continued use of half of the farm that had been deeded over to him, and refers to the<br />

arrangement that they have made regarding said farm. He also instructed that his<br />

three daughters (Elizabeth, Gertien, and Catherine) be sent to school to learn “reading,<br />

writing and sewing.” In this instrument, Adam <strong>Pitcher</strong> also makes reference to his<br />

21<br />

“negro girl named Flora” and to his indentured boy, Fred.<br />

19 H.H. Morse, Historic Old Rhinebeck, Pocantico Printery, Flocker & Hicks, Tarrytown-on-<br />

Hudson, NY, 1908<br />

20<br />

21<br />

“Dutch Selected Reformed Church VItal Records, 1660-1926,” Holland Society of New York<br />

Dutchess County Surrogate Court, will of Adam <strong>Pitcher</strong>, probated 12 September 1768<br />

11

The southern half of the property Peter deeded to his older son <strong>William</strong> “in<br />

consideration of the natural love and affection which he hath and beareth to his<br />

22<br />

son...also for the sum of five shillings.” The deed specifies “the parcel of land...or<br />

farm now in the possession of <strong>William</strong> <strong>Pitcher</strong>.” In 1768 <strong>William</strong> <strong>Pitcher</strong> was 43 years<br />

old. According to the Rhinebeck tax records, he had been paying property taxes there<br />

23<br />

since 1753.<br />

<strong>William</strong> <strong>Pitcher</strong> married Magdalena Donsbach on 5 November 1748 at the Germantown<br />

Reformed Church, when he was 23 and she was 21. The first of their children, Peter,<br />

was born in 1750 and baptized at St. Peter’s Lutheran Church in Rhinebeck.<br />

Subsequent children of <strong>William</strong> <strong>Pitcher</strong> were baptized at St. Paul’s Lutheran Church in<br />

what is now Red Hook. They did not precisely follow the tradition of the Dutch and<br />

Germans of naming the first son after the paternal grandfather, the first daughter after<br />

the maternal grandmother, second son after the maternal grandfather, and second<br />

daughter after the maternal grandmother. After Peter (named for Peter <strong>Pitcher</strong>) came<br />

Margaretha in 1752 (for Margaretha Scheffer), Magdalena in 1754, then Wilhelm in<br />

1756, Heinrich in 1762 (for Heinrich Donsbach), and Catherina in 1764 (for Catherina<br />

Phillips). It is not clear what happened to Magdalena Donsbach.<br />

After Adam <strong>Pitcher</strong>’s death in 1768, his widow, Anna Maria Richter married his brother,<br />

<strong>William</strong> <strong>Pitcher</strong>. Together they had Elizabeth in 1771 (named for Elizabeth Stahl), Philip<br />

in 1774 (sponsored by Philip Staats and Anna Maria Benner), John W. in 1776 (named<br />

for Johannes RIchter), Anna in 1779 (sponsored by Hendrick Bender and Annatjen<br />

24<br />

Richter), and Jacob in 1781 (sponsored by Jacob Richter and Magdalena Phillips).<br />

The first US Census data, from 1790 has nine people in the household of <strong>William</strong><br />

22<br />

23<br />

Dutchess County Clerk’s Office, Deeds, “Peter Bitcher” to “<strong>William</strong> Bitcher,” 25 May 1768<br />

Dutchess County New York Tax Lists 1718-1787, Clifford M. Buck, Kinship (Press),<br />

Rhinebeck, New York, 1991<br />

24<br />

“Dutch Selected Reformed Church Vital Records, 1660-1926,” Holland Society of New York<br />

12

<strong>Pitcher</strong>: four free white males, one over 16 years old and three under 16; three free<br />

white females; and two slaves. The free white males would have been <strong>William</strong> and his<br />

sons, Philip, John W., and Jacob; the free white females, Anna Maria Richter, Elizabeth,<br />

25<br />

and Anna.<br />

The <strong>Pitcher</strong>s, Generations IV-VII<br />

Before <strong>William</strong> <strong>Pitcher</strong> died in 1800, he willed that his property “all that farm which I<br />

got from my father, Peter <strong>Pitcher</strong>, on which I now live and reside, together with the<br />

houses, and buildings standing on the same” go to his three youngest sons: Philip (26),<br />

John W. (24), and Jacob (19). <strong>William</strong> <strong>Pitcher</strong> instructed that the remainder of his<br />

estate be divided between all of his children: Peter, Hendrick, Philip, John, Margaret,<br />

Catherine, Elisabeth, and Annatie, and the children of his son Wilhelmus. Jacob<br />

<strong>Pitcher</strong>’s health or habits were questionable based on the following line in his father’s<br />

will: “…if in case my son Jacob should die before he can receive the estate hereby<br />

divised to him… .”<br />

At the time of his death, <strong>William</strong> <strong>Pitcher</strong>’s house and farm were valued at $4,370 and<br />

his personal property at $824. In 1800, after their father’s death, Philip and John W.<br />

were jointly assessed (no mention of Jacob) for the house and farm valued at $4,370<br />

and personal property, presumably farm equipment and livestock, of $257. Their tax<br />

bill was $8.09.<br />

John W. and Philip <strong>Pitcher</strong> owned their father’s farm jointly, but apparently lived<br />

separately on it. The 1800 US Census lists John W. and Philip <strong>Pitcher</strong> each as heads of<br />

households. A map surveyed by Alexander Thompson in 1797 (MAP 9) shows five<br />

houses on the north side of <strong>Pitcher</strong> Lane and a red building labeled “Martin’s Inn.” The<br />

25 1790 United States Census, s.v. <strong>William</strong> <strong>Pitcher</strong>, Rhinebeck, Dutchess County, New York,<br />

accessed through ancestry.com<br />

13

uildings, matched with the names on the 1800 census are, from west to east,<br />

Nicholas Hoffman, <strong>William</strong> Vredenbergh (sic), John W. <strong>Pitcher</strong>, Philip <strong>Pitcher</strong>, Ebenezer<br />

Punderson, and Henry Martin. A map surveyed in 1799 by Philip Reichert confirms the<br />

properties at the west end of <strong>Pitcher</strong> Lane (MAP 10). John W. <strong>Pitcher</strong> had married<br />

Catherine Kip on 4 November 1797 at St. Paul’s Lutheran Church, and in 1800 they<br />

shared their household with a free white female between 10-16, probably a servant; a<br />

26<br />

free white female under 10; their infant daughter Helen; and two slaves. Philip<br />

<strong>Pitcher</strong> had married Catherine Wilson around 1796, and in 1800 they were living with a<br />

free white male (servant) between 16 and 26; two young daughters, Elizabeth and<br />

27<br />

Anna Maria; and two slaves.<br />

Rhinebeck tax records, available through 1803, assess John W. and Philip jointly for the<br />

28<br />

house and farm. In 1806, the brothers divided the farm north and south based on a<br />

survey by their neighbor Nathan Beckwith (MAP 8), but the division was not recorded<br />

until 1860, after both Philip and John W. were dead.<br />

In 1810 the household of John W. <strong>Pitcher</strong> and Catherine Kipp <strong>Pitcher</strong> was comprised of<br />

themselves, their sons John Henry (5), Abraham (3), and <strong>William</strong> (0), their daughter<br />

Helen (9), two white male and one female laborers between 10 and 15 years old, and<br />

29<br />

two slaves, for a total of eleven people.<br />

26 1800 United States Census, s.v. John W. <strong>Pitcher</strong>, Rhinebeck, Dutchess County, New York,<br />

accessed through ancestry.com<br />

27 1800 United States Census, s.v. Philip <strong>Pitcher</strong>, Rhinebeck, Dutchess County, New York,<br />

accessed through ancestry.com<br />

28 “Assessment of all the Real and Personal Estate in the Town of Rhinebeck” 1799-1803,<br />

Series B0950, New York State Archives, Albany, New York<br />

29 1810 United States Census, s.v. John W. <strong>Pitcher</strong>, Rhinebeck, Dutchess County, New York,<br />

accessed through ancestry.com<br />

14

John W. <strong>Pitcher</strong> is always referred to with his middle initial because a John <strong>Pitcher</strong>, born<br />

in 1750 and distantly related, also lived in Dutchess County in the nearby town of<br />

Northeast.<br />

By the early 19th century, <strong>Pitcher</strong> Lane had become a major thoroughfare between<br />

Upper Red Hook and beyond into Northeast and Connecticut and also the landings on<br />

the Hudson River at Barrytown and Tivoli. The Hudson had always been a link to the<br />

steady demand of New York City for produce, livestock, and grains. Robert Fulton<br />

perfected the steamboat in 1807, which made trade on the river more reliable and<br />

efficient. John W. <strong>Pitcher</strong> had inherited a large agricultural operation and increased its<br />

acreage by purchasing land that had belonged to his grandfather Peter. According the<br />

1816 Agricultural Schedule, the assessed value of John W. <strong>Pitcher</strong>’s farm was $6,700<br />

and he had personal property of $400. Until the opening of the Erie Canal in 1825,<br />

farmers in the Hudson Valley, along with taking care of their own and local needs, grew<br />

wheat for production as well as potatoes, onions, and other sturdy crops that could be<br />

easily shipped. Competition from the West, along with an insect blight in the<br />

mid-1830s, pushed local farmers toward sheep, which supplied the woolen mills on the<br />

nearby White Clay Kill and Sawkill creeks, and fruit, which the loamy soil of the area<br />

proved well suited.<br />

Along with being a successful farmer, John W. <strong>Pitcher</strong> was an active member of the<br />

Upper Red Hook community. He served in the New York State Militia, attaining the rank<br />

30<br />

of First Lieutenant in 1807 and Captain in 1812. Along with his brother Philip,<br />

Nicholas Hoffman, Nathan Beckwith and other neighbors, John W. contributed to the<br />

founding of the Mountain View Academy in 1822, with the following statement:<br />

Believing that well conducted schools affording the opportunity of moral and literary<br />

improvement to our youth are in every respect highly beneficial, and desirous of establishing a<br />

Classical School or Academy in the village of Red Hook, which is intended to place under the<br />

30 Military Minutes of the Council of Appointment of the State of New York, 1783-1821 Vol.I, J.B.<br />

Lyon, State Printer-New York, 1901, p.939 and Vol. II, p.1324<br />

15

direction of twelve trustees to be annually elected by the subscribers to the Academy in which<br />

school it is intended that reading, writing, arithmetic, English grammar, surveying, navigation,<br />

geography, public speaking together with the Latin and Greek languages shall be taught and a<br />

scrupulous attention to the moral and religious habits of the students shall be observed: Under<br />

these impressions and desirous of public utility, we, the subscribers promise to pay to the<br />

Trustees of Red Hook Academy the sums affixed to our respective names to be appropriated for<br />

the object above mentioned. 31<br />

The <strong>Pitcher</strong>s—John W. and Catherine, Philip and Catherine, all of their children and their<br />

extended families—were members of St. John’s Reformed Church, which was built in<br />

1787 as an adjunct to the Red Church at the Lower Red Hook Landing (now Tivoli) in<br />

response to the developing settlement at Upper Red Hook. The new church was<br />

referred to as “the Church at the Road” because it was located at the Post Road. John<br />

W. and Catherine became members of St. John’s Low Dutch Reformed Church in Upper<br />

Red Hook in 1806, transferring their allegiance from St. Paul’s. John W. became a<br />

deacon in 1807 and their youngest son, born in 1812, was named Andrew Kittle<br />

<strong>Pitcher</strong> after the long serving minister, who was also instrumental in the founding of<br />

the Academy, Andrew Kittle.<br />

The <strong>Pitcher</strong> household reached a peak population of 14 in 1820 with John W.,<br />

Catherine, John H., Abraham, <strong>William</strong>, Andrew, Helen, one white male over 45 (a laborer<br />

or father-in-law), one free white female 26-44, in addition to Catherine (a servant or<br />

other relative), one slave male under 14, one slave male over 45, and two<br />

32<br />

“foreigners.”<br />

Prior to 1850, only the name of the head of household is listed on the US Census, and<br />

each census records slightly different data. Between 1790 and 1820, individuals were<br />

31 St. John’s Reformed Church archives, printed in Upper Red Hook: An American Crossroad,<br />

Roger M. Leonard, published by the author, 2012, p.70<br />

32 1820 United States Census, s.v. John W. <strong>Pitcher</strong>, Red Hook, Dutchess County, New York,<br />

accessed through ancestry.com<br />

16

noted based on gender, age, race, and free or slave status. Slavery was outlawed for<br />

all in 1827, but in the 1830 census only gender and age were recorded. In the 1840<br />

record, gender, age, and race were noted. After 1820, the <strong>Pitcher</strong> household gradually<br />

declined in size: son John Henry became a minister after attending Union College in<br />

Schenectady and New Brunswick Seminary; Abraham acquired land on the south side of<br />

<strong>Pitcher</strong> Lane to farm and built or moved into an existing house there; <strong>William</strong> graduated<br />

from <strong>William</strong>s College and Princeton Seminary, becoming a minister as well<br />

33<br />

; Andrew<br />

K., the youngest son, stayed on his father’s farm. In 1830 there were eight people<br />

34<br />

living in John W. <strong>Pitcher</strong>’s house. In 1840 there were only six: John W., his wife<br />

Catherine, their son Andrew, a 15-20 year-old female (white), a ‘free colored male’<br />

10-24, and a ‘free colored female 24-36.’ 35<br />

Beginning in 1851 the Hudson River Railroad became the mode of transportation for<br />

shipping farm goods to market in New York City and abroad. The river landings at<br />

Tivoli and Barrytown became station stops. Red Hook became known for its apple<br />

orchards. In 1855 the town production was 14,873 bushels; by 1865 it was up to<br />

36<br />

38,230 . On the 1850 Gillette map (MAP 11), the farms along <strong>Pitcher</strong> Lane from west<br />

to east belonged to Cornelius Elmendorf, who had married John W. <strong>Pitcher</strong>’s niece Anna<br />

Maria; John W. <strong>Pitcher</strong>; <strong>William</strong> W. <strong>Pitcher</strong>, son of J.W.P.’s brother Philip (who had died<br />

in 1844); and on the south side of the road John W.’s son Abraham. In 1850,<br />

according to the census, John W. <strong>Pitcher</strong> shared the house with his son Andrew (38),<br />

Andrew’s wife Mary Ann Hoffman (36), their children Laura (5), and <strong>William</strong> (2), and<br />

Susan Hoffman, Mary Ann Hoffman <strong>Pitcher</strong>’s mother (66). John W. had by then<br />

33 Upper Red Hook: An American Crossroad, Roger M. Leonard, published by the author, 2012,<br />

p.60<br />

34 1830 United States Census, s.v. John W. <strong>Pitcher</strong>, Red Hook, Dutchess County, New York,<br />

accessed through ancestry.com<br />

35 1840 United States Census, s.v. John W. <strong>Pitcher</strong>, Red Hook, Dutchess County, New York,<br />

accessed through ancestry.com<br />

36<br />

Benedict Seidman, “Agriculture in Red Hook,” Bard College Senior Project, 1940<br />

17

transferred his farm to his son. Andrew <strong>Pitcher</strong>’s property was valued at $7,000 and<br />

his farm implements at $200. In 1850 he had 78 acres of improved land and 10 acres<br />

of wood lot; 2 horses, 6 milk cows, 1 other type of cattle, 22 sheep, 5 swine, all valued<br />

at $422. He was producing rye, corn, and oats. After John W. <strong>Pitcher</strong>’s death in<br />

1859, Andrew lived in the farmhouse with his wife, five children, one 28-year-old<br />

37<br />

female servant, and a laborer, John Millham (50). The Agricultural Production<br />

Schedule of 1860 shows that Andrew <strong>Pitcher</strong> had increased his yield of rye from 260<br />

bushels to 300, and doubled his oat crop since 1850; but his Indian corn production<br />

decreased by 75% . He had also replaced all of his sheep with swine.<br />

Andrew K. <strong>Pitcher</strong>’s cousin and neighbor to the east, <strong>William</strong> Wilson <strong>Pitcher</strong>, died in<br />

1864 and his one-fifth portion of the original Peter <strong>Pitcher</strong> farm was sold to P.H. Coon.<br />

Abraham <strong>Pitcher</strong> died in 1874 without a will. Six months later a fire destroyed his<br />

house. Abraham’s wife, Eliza Sanderson <strong>Pitcher</strong>, and their children sold his piece of the<br />

original Peter <strong>Pitcher</strong> land on the north side of <strong>Pitcher</strong> Lane in addition to the land he<br />

had purchased on the south side to Francis and Margaret Elting.<br />

On the north side of <strong>Pitcher</strong> Lane, to the west of Andrew <strong>Pitcher</strong>’s house, the Eltings<br />

built a large, ornate Victorian house with a cupola. In 1881, Andrew <strong>Pitcher</strong> sold all of<br />

his land to the Elting’s son, Henry Snyder Elting. One year later, Andrew <strong>Pitcher</strong>’s<br />

daughter, Sarah Jansen <strong>Pitcher</strong>, married Henry Elting. Andrew <strong>Pitcher</strong> lived in the old<br />

house until his death in 1885.<br />

When Margaret Elting died in 1905, she willed all of the land that had belonged to her<br />

and her late husband to her son. Henry Elting farmed this land, growing primarily fruit<br />

and grains until his death in 1927. Henry Elting and Sarah J. <strong>Pitcher</strong>’s daughter<br />

Florence and son-in-law Ezra Cookingham continued farming until 1942 when they sold<br />

37 1860 United States Census, s.v. Andrew K. <strong>Pitcher</strong>, Red Hook, Dutchess County, New York,<br />

accessed through ancestry.com<br />

18

the enterprise to Victory Farms Inc. based in New York City. Intact through several<br />

transfers, the property was sold in 1955 to Robert G. Greig, who in 1942 had<br />

purchased and was farming the land next door that had belonged to Philip <strong>Pitcher</strong>. For<br />

a short time, the south half of Peter <strong>Pitcher</strong>’s original farm was reassembled.<br />

The Past 73 Years<br />

The <strong>William</strong> <strong>Pitcher</strong> farm was sold again several times between 1955 and 2000.<br />

Six generations of <strong>Pitcher</strong>s and their descendants lived within the original 550 acres<br />

purchased 200 years before. Andrew was the last <strong>Pitcher</strong> to live in the old farmhouse.<br />

After his death it was insconsistently inhabited by seasonal or tenant farmers. In each<br />

census after 1880, the names in the house are different and they are all listed as farm<br />

laborers and renters.<br />

The house has been empty since 2000, but the land is under cultivation, providing feed<br />

crops and produce for local consumption and farmers’ markets as far south as<br />

Manhattan and into southwestern Connecticut.<br />

Other than the one-story circa 1900 addition, which may have been added as a second<br />

kitchen to make the house more comfortable for two families at a time, and the later<br />

insertion of a bathroom, no major alterations have been made to the house since<br />

before 1800.<br />

The <strong>Pitcher</strong> house is an excellent example of an early to mid-18th-century Dutch<br />

building with a Palatine overlay, which was common in this area. For the sake of study,<br />

neglect has been its salvation.<br />

19

DESCRIPTIONS<br />

THE SITE<br />

The <strong>William</strong> <strong>Pitcher</strong> Farm is set back 250<br />

yards from the north side of <strong>Pitcher</strong><br />

Lane, approximately three miles north<br />

of the village of Red Hook. <strong>Pitcher</strong> Lane<br />

is a quiet east-west road, a mile and a<br />

half long connecting Route 9 (formerly<br />

known as the Post Road or the King’s<br />

Highway), to County Route 79, also<br />

known as Budds Corners Road, formerly<br />

referred to as the road to Red Hook<br />

Landing. The house faces due south<br />

with a line of large locust trees marking<br />

the route that the driveway followed<br />

years ago.<br />

The current driveway continues past the<br />

house on the east side to a barn<br />

complex. The core of this structure is a<br />

mid-19th century, square-rule Englishstyle<br />

hay barn, built into a bank, with a<br />

dry-laid bluestone foundation that has<br />

remnants of limewash or parging on the<br />

Aerial photo of the <strong>William</strong> <strong>Pitcher</strong> farm property,<br />

house and barns in south-east corner, 2014.<br />

(http://geoaccess.co.dutchess.ny.us)<br />

inside. On the north side there is a late<br />

19th-early-20th century addition that housed calves. Attached to this section is a<br />

concrete silo. Beneath the hay barn, and extending out from the west <br />

20

side is a mid-20th-century concrete-block<br />

framed dairy barn. This section has a concrete<br />

floor with gutters, remnants of stanchions, and<br />

a dairy room. The last addition is a two-bay<br />

structure coming off the south gable end of the<br />

hay barn. One bay is for storage and the other<br />

appears to have been a common room for<br />

laborers with lockers and a table and chairs. To<br />

the east of this complex are a free-standing<br />

horse shed and a corn crib.<br />

The house and barns are located at the southeast<br />

corner of an 86-acre parcel of land, nearly half of which<br />

is under cultivation. The property is bordered to the<br />

north, east, and west primarily by open agricultural land.<br />

The southern boundary of the property is <strong>Pitcher</strong> Lane.<br />

Carved out of the southern edge of the property to the<br />

west of the WIlliam <strong>Pitcher</strong> farmhouse is a three-acre<br />

parcel of land with a large Italianate Victorian house on<br />

it that dates to 1875. This lot was part of the <strong>Pitcher</strong><br />

family property until the mid-20th century.<br />

21

DESCRIPTION +<br />

CONDITION ASSESSMENT<br />

EXTERIOR<br />

The <strong>Pitcher</strong> house is a one-and-one-half story, five-fenestration bay, Dutch-framed<br />

wooden structure with a moderate to steeply pitched gable roof that runs parallel to<br />

the main facade, a small, one-story addition off the west gable end, and an ell that<br />

extends from the north side of the east end. The main house and the ell sit on<br />

foundations of dry-laid bluestone, and both are clad in cement-asbestos siding.<br />

There is an inboard brick chimney at the peak on the east gable end and a patch on the<br />

west gable end, where a chimney was removed following a chimney fire in the later<br />

20th century. There is also one brick chimney at the north gable end of the ell.<br />

The roof is covered with hand-worked, standing-seam metal.<br />

The house appears to have been a nine-bent structure of two rooms with a Dutch-style<br />

jambless fireplace located in the middle. The ell was a free-standing, five-bent<br />

structure, perhaps a summer kitchen, which also had a jambless fireplace set off about<br />

eight feet to the north of the house and staggered eight feet to the east. Visible<br />

evidence inside the house supports the contention that the two structures were joined<br />

near the end of the 18th century.<br />

Recommendations for repair in this section are merely for stabilization and preservation<br />

purposes as first steps toward a full renovation. A more comprehensive approach is<br />

outlined in a later section.<br />

22

SOUTH ELEVATION<br />

South elevation 2004 (Darlene S. RIemer Architect P.C. ) The dotted line shows the east end of the original house.<br />

The main section of the house is 46’ long by 25’ deep with a one-room addition at the<br />

west end. The main entrance is located two feet off center to the east. The<br />

architrave around the door and 6/6 sidelights date to their installation, but the door is<br />

a “colonial-style,” six-panel metal door that is substantially both narrower and shorter<br />

than the original, and the door frame is filled to make up the difference. This entrance<br />

configuration was likely created during the major renovation around 1775, which saw<br />

the east gable end extended by two anchor bents (eight feet) in order to line up with,<br />

and join with, the auxiliary five-bent structure; abandonment of the center jambless<br />

fireplace in favor of English-style fireplaces at the east and west gable ends; creation of<br />

a center hall by removing an anchor beam and reframing the ceiling.<br />

The asbestos siding was installed around a porch, nine feet wide, which had handrails<br />

that returned to the building. This may have been a version of an early Dutch-style<br />

stoop with facing benches.<br />

There are two 1/1 replacement windows nearly symmetrically placed on either side of<br />

the entrance. Early flat window casing is visible with aluminum triple-track storm<br />

23

South elevation 2014<br />

windows applied to it. A wall-dormer with 6/6 single-hung sash sits off-center two feet<br />

to the west above the entrance, with its face on the same plane as the front of the<br />

house.<br />

CONDITION ASSESSMENT<br />

• The standing-seam metal roof is in fair condition. It was last recoated with aluminum<br />

paint around 2004.<br />

• The asbestos siding is in poor condition, especially at the lower courses as a result of<br />

the house being at grade, with no drainage.<br />

• All six panes of glass are missing from the bottom sash of the west sidelight.<br />

• All of the window sills are deteriorated.<br />

• All door and window trim need consolidation and repair, replacement, or<br />

reconstruction.<br />

24

• A 6’x8’ concrete slab, poured directly against the sill outside the entrance door,<br />

caused catastrophic rot and failure of the mortise pocket holding the joist spanning<br />

the depth of the house. This joist has been jacked up and supported recently.<br />

East elevation 2004 (Darlene S. RIemer Architect P.C. ) The dotted line shows the end of the five-bent structure.<br />

EAST ELEVATION<br />

The east elevation of the <strong>William</strong> <strong>Pitcher</strong> house faces an expanse of fields, which were<br />

part of the original Peter <strong>Pitcher</strong> farm. At the far east end of these fields is a small<br />

house that was built by <strong>William</strong>’s son Philip, around 1800.<br />

The east elevation of the <strong>William</strong> <strong>Pitcher</strong> house, which is 25’ wide and 22’ tall at the<br />

peak, has a bulkhead to the basement, which replaced an earlier entrance on the south<br />

side. The brick of the back of the fireplace is exposed as is common in this area. On<br />

either side of the brick, asymmetrically placed, are two 1/1 double-hung replacement<br />

windows with triple-track storm windows. Above there are two windows, the southern<br />

is a single nine-light sash, which appears to be quite old, and the north is a single-hung<br />

6/6 unit that appears to be original to the circa 1775 renovation. The windows are<br />

25

East elevation 2014<br />

not evenly spaced in relation to the peak. The brick chimney extends up through<br />

through the roof approximately three feet at the peak. The north ell 27’ deep and is<br />

shorter than the main house by 18”. There are two 1/1 double-hung replacement<br />

windows with aluminum storms on the east side of the ell.<br />

CONDITION ASSESSMENT<br />

• Biological growth is overtaking the chimney at the east gable end.<br />

• Asbestos siding is compromised, broken, and in some places missing.<br />

• The bulkhead door is missing, leaving the basement open to the weather and<br />

intruders.<br />

• The house is sitting right at or slightly below grade, which has likely caused sill<br />

damage.<br />

• Window sills are rotted due to moisture trapped by storm windows.<br />

26

NORTH ELEVATION<br />

North elevation 2004 (Darlene S. RIemer Architect P.C. )<br />

The north gable end of the ell is 22’ wide and 20’ tall at the peak. The ground slopes<br />

away to the north, exposing two feet of the dry-laid stone foundation at this end. One<br />

foot in from the east corner is a single-light metal door with brick-mold casing. This<br />

door opens onto a wooden landing with three steps down to grade. Placed<br />

symmetrically above are two window openings, covered with sheets of plexiglass. The<br />

trim around these windows is wood. The roof does not project out beyond the walls of<br />

the house beyond an inch or two. There are no eaves or rakes. The brick chimney at<br />

the north gable end of the ell extends up through the roof at the peak by one foot or<br />

less.<br />

The north elevation of the main house, which is nine feet high at the eave in addition to<br />

two feet of exposed foundation, has no visible windows or doors. A 20th-century<br />

block chimney for a wood stove runs up the outside, piercing the eave and extends up<br />

another nine feet.<br />

There is a bulkhead opening to the basement (B1) under the west addition.<br />

27

The north elevation of the west addition has one 6/6 double-hung sash with an<br />

aluminum storm.<br />

North elevation 2014<br />

CONDITION ASSESSMENT<br />

• Biological growth is causing damage to the chimney and the siding.<br />

• The chimney is in need of reconstruction above the roof.<br />

• Asbestos siding is missing, exposing asphalt shingle siding and sheathing beneath.<br />

• The metal door is badly rusted.<br />

• Door and window trim are rotted as a result of years without maintenance.<br />

• There is no bulkhead door covering the stairs to the basement.<br />

• The stone foundation on the north side was at some point, perhaps when the west<br />

addition was added, coated with concrete, which over time has trapped moisture and<br />

in places damaged the foundation through freeze-thaw cycles.<br />

28

WEST ELEVATION<br />

West elevation 2004 (Darlene S. RIemer Architect P.C. )<br />

The story-and-a-half ell extends out 25’ from the north side of the main house. There<br />

is one 6/6 single-hung window with an aluminum storm, which lines up with the window<br />

on the other side of the ell, nine feet in from the gable end. One foot in from the main<br />

house, beginning four feet up, is a late 20th-century, single-pane, awning window.<br />

The west gable end of the main house has one replacement 1/1 window on the first<br />

story, tight against the west end addition. There are two replacement 1/1 windows<br />

above and nearly centered on the peak.<br />

The one-story addition on the west end, circa 1900, is stepped back five feet from the<br />

front facade and sits on a poured concrete foundation. The extension, which contains<br />

a kitchen, extends west 16’ and is 14’ wide across the gable end. On the front, the<br />

south side, there is an entry door with a 6/6 double hung window to the right. The<br />

west and north sides each have one 6/6 double-hung sash. The exterior cladding is<br />

asbestos shingle, with asphalt shingle beneath and novelty siding as the original finish.<br />

The north side of the main house is windowless. The ell off the north side on the east<br />

end extends back 25’ and is 22’ wide at the gable. The west side of the ell has one<br />

29

original 6/6 single-hung window on the first floor, a door in the north wall and a<br />

replacement 1/1 double-hung window on the east side.<br />

West elevation 2014<br />

CONDITION ASSESSMENT<br />

The west side of the ell has experienced significant failures and losses.<br />

• The corner where the ell meets the main house has been significantly damaged by<br />

water over time. Siding, sheathing, and the small awning window are gone.<br />

• The 6/6 window in the ell took on and held water at some point, which caused the sill<br />

to rot away completely, taking with it all the nogging, sheathing, and siding in and on<br />

the wall beneath. Given the amount of water damage, and that the house is very<br />

near grade along the west wall of the ell, the sill is likely compromised as well.<br />

• Asbestos siding is missing, exposing asphalt shingle siding and sheathing beneath.<br />

• Window sills are rotted from storm windows and years without maintenance.<br />

• The stone foundation on the west side was at some point, perhaps when the west<br />

addition was added, coated with concrete, which over time has trapped moisture and<br />

in places damaged the foundation through freeze-thaw cycles.<br />

30

IMMEDIATE EXTERIOR RECOMMENDATIONS<br />

• Remove all biological growth from exterior.<br />

• Reconstruct, repoint chimneys as needed.<br />

• Remove flaking roof material and rust; repair as needed (where ell meets main house)<br />

and coat with elastomeric acrylic.<br />

• Regrade around the building and install curtain drains daylighting to low area to the<br />

northwest of the house.<br />

• Remove cement from foundation on north and west; repair as needed.<br />

• Remove lower courses of siding and sheathing to inspect sills; scarf in repairs/replace<br />

sills as needed.<br />

• Remove aluminum storms and repair, restore, reglaze old sashes. Remove<br />

replacement 1/1 units, repair and restore old jambs, sills, and trim.<br />

• Repair bulkhead door areas and enclose.<br />

31

DESCRIPTION +<br />

CONDITION ASSESSMENT<br />

INTERIOR<br />

The <strong>Pitcher</strong> farmhouse consists of three levels: the cellar, the main floor, and the<br />

garret. The house originally had two rooms on the main floor, separated by a central<br />

jambless fireplace, a garret above, and a cellar below under the east half. The house as<br />

originally built was a nine-bent structure, 38’ along the eave by 25’ deep. It was<br />

framed in the Dutch style typical of the area.<br />

“The hallmark of Dutch American framing logic is its simplicity.” 1<br />

Dutch structures consist of a series of H-<br />

shaped “bents that are lined up, one<br />

behind the next (figure 1). Massive beams<br />

connect each pair of posts with a pegged<br />

mortise-and-tenon joint, to form a bent.<br />

Bents are closely spaced, typically 3-1/2’<br />

and 5-1/2’ apart. Each bent is mortised<br />

into sill and top plates that run the length<br />

of the eaves. Rafter pairs are generally set<br />

above each bent. The typical joint<br />

between the rafter and collar beam is a<br />

half dovetail. The size of the house is<br />

determined by the number of bents. For<br />

example, a five bent house would be<br />

between 14’ and 22’ long and as wide as<br />

the anchor beam. The Dutch tended to<br />

live compactly, often in a one-room<br />

structure with a garret for storage and<br />

figure 1- the eight-bent, center-chimney Winne<br />

House 1751 (Timothy J. Gallagher 2005,<br />

Metropolitan Museum of Art)<br />

1 Clifford W. Zink, p. 273, “Dutch Framed Houses in New York and New Jersey,”<br />

Winterthur Portfolio, Vol. 22, No. 4<br />

32

some sleeping, accessible by a ladder or by an<br />

enclosed set of stairs to keep the heat in the living<br />

space. The defining feature of a Dutch house is the<br />

jambless fireplace (figure 2). The large open hearth<br />

supported by either an arch or a cradle braced<br />

against a lintel or corbel stone projecting from the<br />

foundation wall, and a chimney beginning on the<br />

second floor, supported by short trimmer beams,<br />

to extend through the roof. What is now the ell off<br />

the north side was a separate five-bent structure,<br />

with a jambless fireplace at the north gable end,<br />

and a garret above. This structure, likely a summer<br />

kitchen, was situated approximately eight feet to<br />

the north of the main house and offset about eight<br />

feet to the east.<br />

The interior spaces reflect, with the exception of<br />

the insertion of a bathroom into the front hall, a<br />

reconfiguration and renovation that likely<br />

occurred in the last quarter of the 18th century.<br />

figure 2- jambless fireplace (Dutch Barn<br />

Preservation Society, Newsletter Spring 1998,<br />

Vol. 11, Issue 2)<br />

There were three campaigns of alterations to this structure, each likely corresponding<br />

to a population increase, to a death in the family, and a change of ownership.<br />

This change of configuration from center chimney to center hall was a common update<br />

to mid-18th-century houses in the area. The first and most structurally significant<br />

renovation involved removal of the center chimney, shifting the third anchor bent,<br />

removing the fourth anchor bent completely, creating a center hall, adding two bents<br />

to the east gable end of the house, which increased the total length to 46’ and<br />

brought the gable end in line with the east wall of the summer kitchen, constructing<br />

English-style fireplaces at the east and west ends, applying Federal-style windows and<br />

moldings, and attaching the free-standing five-bent summer kitchen building to the<br />

north side. These alterations reflect stylistic changes that were appropriate between<br />

2<br />

1770 and the early 1800s. The renovation also reflected changes in the life of <strong>William</strong><br />

2<br />

Nancy Kelly, Dutchess County Historical Society 2005-2006 Yearbook , Vol. 85, p.76<br />

33

<strong>Pitcher</strong>. When he received title to the farm, house and 275 acres from his father Peter<br />

in 1768, <strong>William</strong> was already living in this house with his wife Magdalena Donsbach, five<br />

children, and probably two slaves. Six years later, <strong>William</strong> <strong>Pitcher</strong> had married a second<br />

time and had produced five more children with his brother Adam’s widow, Anna Maria<br />

Richter. The confluence of the death of his father, becoming the owner of a substantial<br />

farm, and the increased population of his household, likely spurred the first campaign of<br />

improvements to the homestead. Often, as in the case of the Christian Moore house<br />

approximately one mile away to the northwest, and in the Heermance house one mile<br />

to the northeast, the later 18th-century renovation involved adding four or five bents<br />

and an end chimney to an existing five-bent structure that already had a chimney at<br />

one gable end.<br />

The door hardware upstairs—HL hinges and the ghosts of HL hinges, and Norfolk<br />

latches—suggests that rooms were first partitioned in the late 18th or early 19th<br />

century. <strong>William</strong> <strong>Pitcher</strong> died in 1800, leaving the house to his son John W. <strong>Pitcher</strong>.<br />

The population of the household grew from nine people in 1790 to thirteen people in<br />

1820. The combination of these factors, along with changing attitudes toward privacy<br />

and access, would have contributed to this second campaign.<br />

The last significant stylistic change to the house occurred around 1860, when Andrew<br />

<strong>Pitcher</strong> inherited the property upon the death of his father, John W. <strong>Pitcher</strong>. Plain<br />

beaded door trim and baseboard on the main floor in rooms 106 and 107 reflect the<br />

taste of that time.<br />

34

THE CELLAR: Description and Condition<br />

N<br />

B4<br />

LINTEL<br />

B3<br />

B2<br />

B1<br />

patched opening<br />

sill rotted<br />

Cellar- plan view 2004 (Darlene S. Riemer Architect P.C. )<br />

B1 B2 B3<br />

Section view, from rear/north 2004 (Darlene S. RIemer Architect P.C. )<br />

35

CELLAR SPACE B1<br />

Beneath the eastern end of the main house, the east room (105) and the center hall<br />

(103/104), Room B1 is 26’ east-west by 25’ north-south and 6’ 6” from the floor to<br />

the bottom of the beams.<br />

Floor: The cellar appears to have a dirt floor, but it is unclear if this is due to<br />

infiltration.<br />

Walls: The foundation is bluestone rubble, which appears to have been laid up with<br />

mortar. It has been repointed and there is remnant lime parging indicating that the<br />

space was functional. The foundation was expanded 8’ to the east to accommodate<br />

the enlarged circa 1775 footprint of the house. It appears that the bulkhead entrance<br />

was relocated at that time, allowing access from the east side rather than from the<br />

south.<br />

At the west end of B1, 3’ from the floor surface, the lintel stone for support of the<br />

hearth projects out 5”. This stone is 8’ long and centered on the wall (photo B1-1). In<br />

the northwest corner are stairs leading up to an exterior door (hidden behind asbestos<br />

siding) on the north side, and to a door beneath the stairs, which would have opened<br />

into the center hall (now Room 104).<br />

Rubble walls support the English-style fireplace above at the east end. This enclosed<br />

area has rough plank shelves.<br />

Ceiling: The ceiling is made of the original floorboards from the rooms above. The<br />

massive beams that span the cellar north-south are 10”x14” by 25’ long and appear to<br />

be chestnut. Trimmer beams, 10”x14” by approximately 4’ long span the first two<br />

beams at the east and west ends.<br />

Systems: An oil-fired furnace was installed in B1. It appears to be at least 40 years<br />

old and is vented through the chimney. There is also a retro-fitted 55-gallon drum for<br />

burning wood attached to the duct system. Sheet metal ducts deliver hot air through<br />

floor vents downstairs. Crude openings in the foundation on the west and north side<br />

allow vents to pass heat to the rest of the main floor. There is a panel box to the left<br />

of the lintel stone on the west wall. Also visible in the basement is the plumbing for<br />

the only bathroom in the house (104), including the main waste line that exits the<br />

building on the north side. None of these systems are functional at this time.<br />

36

Condition: B1 has moisture issues. Water is able to infiltrate through several large<br />

openings in the envelope. Most notably, there is a lack of appropriate covering over<br />

the bulkhead opening, and the area under the front entrance where the sill rotted away<br />

completely due to having had a concrete pad poured against it sometime in the 20th<br />

century (photo B1-2). The loss of this section of sill caused one of the main support<br />

beams spanning the cellar to drop about two feet, taking the trimmer beams with it.<br />

This beam has since been jacked back up and stabilized.<br />

Lack of gutters and the fact that the house sits at grade or slightly below on the south<br />

side are contributing to this moisture problem.<br />

The foundation is bowing in considerably where the original bulkhead entry was located.<br />

The vertical lines of the patch are quite clear where the opening was.<br />

37

photo B1-1- bulge in foundation at orignial<br />

bulkhead<br />

photo B1-2- top view of lintel stone projecting out from west wall of basement<br />

38

photo B1-3- fallen beam due to water<br />

and concrete slab<br />

photo B1-4- furnace and ducts<br />

39

CELLAR SPACE B2<br />

Due to the position of ductwork, it is not possible to get more than a peek into the<br />

crawlspace that is B2 and verify that it is, in fact, a crawlspace and support beams,<br />

similar to those visible in B1.<br />

CELLAR SPACE B3<br />

At the west end of the main house, beneath the circa 1900 addition is cellar space B3.<br />

The cellar is accessed through a bulkhead on the north side of the addition.<br />

Foundation: The foundation is poured concrete, 16’ east-west, 14’ north- south and 7’<br />

deep with a slab floor.<br />

NOTE: At this time it is not possible to get into B3 for further inspection. This<br />

situation will be resolved with a bit of effort and a machete.<br />

CELLAR SPACE B4<br />

Due to the position of ductwork, it is not possible to get even a peek into the<br />

crawlspace that is B4.<br />

B3-1 access to B3<br />

40

IMMEDIATE CELLAR RECOMMENDATIONS<br />

• Remove ALL systems and related ducting, wiring, pipes, etc…<br />

• Support all framing for examination and stabilization.<br />

• Rebuild and repoint foundation as needed.<br />

41

THE FIRST FLOOR: DESCRIPTION<br />

107<br />

106<br />

104<br />

101 102<br />

105<br />

103<br />

Main level plan view 2004 (Darlene S. Riemer Architect P.C. )<br />

The main block of the <strong>William</strong> <strong>Pitcher</strong> house is a one-room deep rectangle, 46’ along<br />

the eaves and 25’ deep, with a small one-room, one-story addition at the west end and<br />

a story and a half ell off the north side. As it stands now there is a central entry<br />

chamber 10’ wide and 14’ deep. A doorway through the left wall of the entry leads to<br />

the west parlor (102), which is 17’ wide. At the far west end of the west parlor is the<br />

circa 1900 addition that appears to have housed a modern kitchen. A doorway<br />

through the right wall of the entry hall leads to the east parlor (105), which is also 17’<br />

wide. At the back of the entry hall are two doors: the left hides a stair that rises and<br />

turns to the left; the right leads to a pass-through full bathroom, beyond which is a<br />

narrow hall that runs along the west side of the ell. The hall gives access to 106,<br />

which is also accessed through the east parlor (105), and opens onto the dry kitchen<br />

(107).<br />

42

ROOM 101, WEST ADDITION<br />

Description: Room 101 is a one-story addition 16’ wide by 14’ deep. Based on the<br />

poured foundation, novelty-style siding and interior finishes of wainscot paneling, it was<br />

built around 1900. Except for the insertion of the bathroom into the center hall, this<br />

was the last major change to the <strong>Pitcher</strong> house.<br />

A modern, metal-clad door gives entry to this room from the outside on the south side<br />

of the house. In the northwest corner is a pantry closet, with a trapdoor cut into the<br />

original sub-floor, which leads to the B3 Cellar Space. The flooring in the rest of the<br />

room is linoleum tiles on top of at least one layer of plywood, on top of the original<br />

pine flooring. Walls are a combination of wallboard and 1960s chipboard paneling over<br />

plaster on lath on all but the north wall and on the outside of the pantry closet, which<br />

are plaster on lath. There is a simple chair rail on the north wall and on the outside of<br />

the pantry with vertically installed bead-board paneling beneath, which appears to be<br />

original. Door trim is flat 1”x6” pine. The windows are 6/6 double-hung sashes which<br />

appear to be from the date of construction. There is one window on each of the south,<br />

west, and north walls. The windows have rounded sills that match the chair rail, and are<br />

trimmed with flat 1”x4” pine. The east wall has a doorway into the west parlor (102)<br />

and a half-wall with a pass-through “window” taking up most of the wall. This opening<br />

was likely created in the 1980s after a fire in the chimney that stood against this wall.<br />

Systems: Room 101 has an antique enamel covered gas stove on the north wall and<br />

feed and drain lines for a sink, which have been cut off at the floor on the east wall.<br />

Electric service in this room consists of one 110-volt outlet on the north wall where BX<br />

wiring has been snaked through the wall; one 220-volt outlet on the west wall for a<br />

stove or dryer; and a florescent light fixture recessed into the wainscot-paneled ceiling.<br />

Finishes: The bead-board ceiling is coated with a thick calcimine-type product. The top<br />

layer of finish on the walls is a latex paint. The surface layer of paint on the door and<br />

window trim contains lead. (APPENDIX VII: Finish Analysis)<br />

43

101-1 looking west from room 102 doorway<br />

44

ROOM 102, WEST PARLOR<br />

Description: Room 102 is 17’ wide and 24’ deep.<br />

The flooring material is plywood, laid over 2”x3”<br />

sleepers, on top of the original flooring. The<br />

north and south walls are plaster on top of riven<br />

lath, nailed to the posts of the anchor posts.<br />

Wall infill is the local version of wattle and daub,<br />

which consists of splits of wood, approximately<br />

3” in diameter and 4’ long, which are tapered at<br />

the ends and fitted horizontally into v-grooves<br />

cut into the sides of the posts of each anchor<br />

bent. (figure 3 and figure 4) The splits serve as a<br />

matrix to hold an infill of mud and straw. At the<br />

west end, next to the doorway and pass-through<br />

window opening to 101, a patched area of the<br />

floor approximately 8’ wide by 3’ deep is<br />

evidence of there having been a hearth stone in<br />

the floor, for a fireplace that was removed in the<br />

1980s. The east wall divides room 102 from the<br />

entry hall (103). The doorway between the two<br />

is centered. To the left of the door, the wall is<br />

covered with horizontally laid planks 12” wide.<br />

To the right of the door, the wall is plaster over<br />

wattle and daub. A portion of the south wall,<br />

between and beneath the windows, is clad in<br />

drywall, as is the west wall. This was likely done<br />

when the replacement windows were installed,<br />

after the west end fireplace and chimney were<br />

removed. The anchor beams are partially clad in<br />

painted “1-by” pine. Macro and microscopic<br />

analysis has determined that they are poplar, as<br />

can also be seen in the Palatine <strong>Farmstead</strong> of<br />

Franz Nehr and the Mathias Progue house in<br />

Rhinebeck, both of which date to the mid-18th<br />

century. The anchor beams, which<br />

figure 3- split lath infill matrix with<br />

mud and straw removed<br />