You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

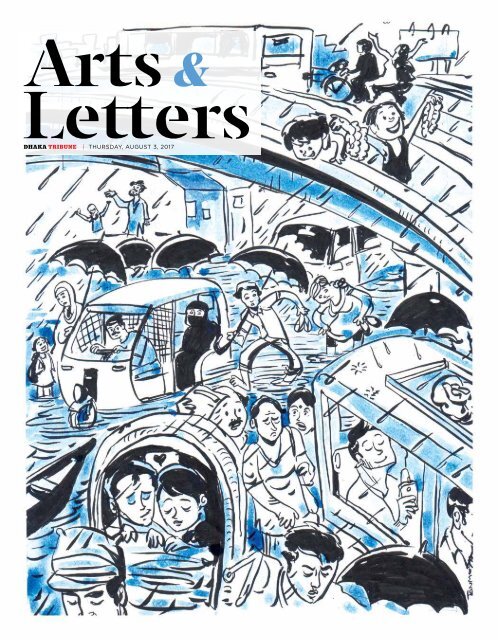

DHAKA TRIBUNE | THURSDAY, august 3, <strong>2017</strong>

Tribute<br />

Editor<br />

Zafar Sobhan<br />

Editor<br />

<strong>Arts</strong> & <strong>Letters</strong><br />

Rifat Munim<br />

Design<br />

Mahbub Alam<br />

Alamgir Hossain<br />

Shahadat Hossain<br />

Cover<br />

Syed Rashad Imam<br />

Tanmoy<br />

Illustration<br />

Syed Rashad Imam<br />

Tanmoy<br />

Priyo<br />

Colour Specialist<br />

Shekhar Mondal<br />

Two songs<br />

of Lalon<br />

(Translated from Bengali by Kaiser Haq)<br />

Lalon Shah, aka Lalon Fakir or Lalon Shain (c. 1772–1890), was the greatest of<br />

the Bauls, the mystic minstrels of Bengal who preached – and practised – a<br />

homegrown humanism and egalitarianism infused with a mix of the Sufi and<br />

Bhakti traditions. Legend has it that he was born a Hindu, and on the way back<br />

from a pilgrimage to the Jagannath Temple in Puri came down with smallpox<br />

and was abandoned by his companions. A Muslim weaver and his wife found<br />

him and nursed him back to health, but he lost one eye to the dreaded disease.<br />

He could not return home since he had lost caste through intimacy with Muslims.<br />

The weaver gave him land to build a house where he embarked on his<br />

new life as a mystic singer-composer. A Baul guru called Siraj Shain, who lived<br />

in the same village, initiated him into the cult. Lalon has had far-reaching influence<br />

on poetry and South Asian culture as a whole. Kazi Nazrul Islam and<br />

Allen Ginsberg owe a debt to him; as does Rabindranath Tagore whose Oxford<br />

lectures, published as The Religion of Man, are infused with Baul philosophy.<br />

Lalon’s shrine in Kushtia, Bangladesh, draws large numbers of pilgrims and<br />

Baul aficionados. The sole likeness of Lalon is a drawing by Jyotirindranath<br />

Tagore, Rabindranath’s elder brother.<br />

Kaiser Haq is Bangladesh’s biggest English language poet. His poetry collections<br />

include Pariah and Other Poems (Bengal Lights Books 2013), Starting Lines<br />

(Dhaka 1978) and A Little Ado (Dhaka 1978). His translations include a novel<br />

by Rabindranath Tagore, Quartet (Heinemann Asian Writers Series, 1993); The<br />

poetry collections: Published in the Streets of Dhaka: collected poems (UPL, Dhaka);<br />

Combien de Bouddhas, a bilingual poetry selection with French translators<br />

by Olivier Litvine (Editions Caracteres, Paris) and the retold Bengali epic: The<br />

Triumph of the Snake Goddess (Harvard University Press).<br />

The mysterious neighbour<br />

In a mirror city<br />

Close by<br />

Lives a neighbour<br />

I’ve never seen<br />

Though I long to see him<br />

How can I reach him<br />

Being like an islander<br />

Amidst endless water –<br />

No boat in sight<br />

Of my curious neighbour<br />

What can I say, for<br />

He has neither limbs nor<br />

Head and shoulders<br />

One moment he’s soaring in space<br />

And floating in water the next<br />

If only he’d touch me once<br />

All fear of death would disappear<br />

He lives where Lalon lives<br />

And yet is a million miles away<br />

Strange bird of passage<br />

A strange bird of passage<br />

Flits in and out of the cage –<br />

God knows how<br />

If only I could catch it<br />

I’d put on its feet<br />

The fetters of consciousness<br />

Eight rooms and nine doors<br />

And little windows piercing the walls<br />

The assembly room right on top’s<br />

a hall of mirrors<br />

What is it but my hard luck<br />

That the bird’s so contrary<br />

It has flown its cage<br />

And hides in the woods<br />

O Heart, beguiled by your cage<br />

You don’t see it’s built of green bamboo<br />

Lalon says ‘Beware! It will fall apart any day.’<br />

[These translations first appeared in the latest issue<br />

of Critical Muslim, a magazine devoted to examining<br />

issues within Islam and Muslim societies.]<br />

• Mahmud Rahman<br />

Near the end of Mahmudul Haque’s novel Kalo Borof, Abdul Khaleq<br />

reaches the Padma.<br />

So this is what it looks like now. What a state!<br />

The Padma has shifted its course quite far. A fleet of sailing boats can be dimly<br />

seen. There is nothing here of what he had imagined. It’s all dried up, derelict.<br />

The name Louhojong flickers in his head like the lights of the distant boats bobbing<br />

in the water. Goalondo, Aricha, Bhagyokul, Tarpasha, Shatnol -he can hear<br />

a deep sigh rising up from the names of those ghats.<br />

Abdul Khaleq had not anticipated this disappointment. What was the point<br />

of coming so far merely for a name Louhojong?<br />

Abdul Khaleq approached the Padma chasing a memory from his childhood<br />

journey from Barasat to erstwhile East Pakistan. One December morning<br />

while visiting Kolkata a few years ago, I made my way to Barasat to seek out<br />

whatever I could find of Abdul Khaleq’s childhood. By then I knew that those<br />

reminiscences were those of the author himself.<br />

After a long, bumpy ride on the DN18 bus along Jessore Road, I stepped off<br />

at Ch<strong>amp</strong>adolir Mor. I did not know if I would find the neighbourhood where<br />

Abdul Khaleq spent his childhood as Poka (his nickname), but I was confident<br />

I would locate Hati Pukur (a pond in the novel). Large public ponds do not<br />

disappear easily.<br />

Indeed, Hati Pukur lay right behind the bus terminal. When I set my eyes<br />

upon it, I caught a gulp in my throat.<br />

So this was what it looked like now. What a state!<br />

In the book, Poka used to walk here with his hand held by his Kenaram<br />

Kaka (uncle). Hati Pukur was described as ringed by huge rain trees. There<br />

was a gazebo in a centre island reached by an iron bridge. Poka and his school<br />

mates traipsed around Hati Pukur soaked in the fragrance of bokul flowers.<br />

The pond is still there, smaller than what I had imagined. The water was<br />

blanketed with algae and the bridge coated with turquoise-coloured corrosion.<br />

The rain trees still stood proud and magnificent, even though they had<br />

shed much of their leaves because this was winter. I looked up and they appeared<br />

to whisper a question: what brings you here?<br />

I had come on a kind of pilgrimage. I was then finishing the English translation<br />

of Kalo Borof. That journey reached a culmination recently when the<br />

translation was published as Black Ice by HarperCollins Publishers, India.<br />

I became a fiction writer while living in the US. When I returned to Dhaka<br />

in 2006 for an extended stay to write a novel, I began seeking out Bangladeshi<br />

A translator’s<br />

journey:<br />

From Kalo Borof<br />

to Black Ice<br />

prose. Beyond the joy of reading, I felt this could add a new layer of complexity<br />

to my own writing. I often write about the same social context taken up by<br />

Bangla writers and it is helpful to absorb how Bangladeshis are written out by<br />

writers from within.<br />

Soon after I arrived, I read an interview by Ahmad Mostofa Kamal of a writer<br />

named Mahmudul Haque. He was unknown to me, but he had apparently<br />

penned many novels and stories from the 1950s to the ‘70s before turning his<br />

back on the literary world around 1981.<br />

I promptly went looking for his books. The search through New Market was<br />

futile. I had better luck at the December Dhaka Book Fair being held at Shilpakala<br />

Academy. From Shahityo Prokash I bought several of his books. The<br />

very next day I read the novel Nirapod Tondra. I scoured Aziz Market for more<br />

books, and soon I read the novels Matir Jahaj and Kalo Borof, along with the<br />

stories in Protidin Ekti Rumal.<br />

I liked the writing so much that I wanted to translate. Mahmudul Haque<br />

deserved to be known outside those who read him in Bangla. I know the value<br />

of translated prose: I had been stimulated by fiction originally written not just<br />

in English but also languages like Portuguese, Gikuyu, Japanese. Why should<br />

the world not receive the best of our Bangla writers then? As a writer of fiction<br />

in English, I felt I could do justice to Mahmudul Haque’s prose.<br />

There was another interest. While absorbed in drafting my novel, I yearned<br />

to work with language on a different plane. Some fiction writers write poetry.<br />

I am not a poet. But I had once made an attempt at literary translation and<br />

enjoyed it. Here I could work with words and sentences at a close level in two<br />

languages. And because in my own novel I was rendering into English conversations<br />

of characters speaking in Bangla, I felt that translating might have a<br />

good effect on my book.<br />

I began with the story “Chhera Taar”. The response to its publication in<br />

the Daily Star was encouraging. Next I chose the title story from Protidin Ekti<br />

Rumal. Dhaka is lax when it comes to author permissions, but I was reluctant<br />

to publish a second story without the author’s consent. I asked around for his<br />

phone number.<br />

I knew he was selective in who he let near him. I carefully rehearsed my<br />

line when I called. In a neutral voice, he heard me out and agreed to have me<br />

come over. When he let me into his flat in Jigatola, I sat in a room crowded<br />

with chairs, coffee and side tables, bookshelves, and a desk piled high with<br />

books and magazines. The book cases looked like they had lain undisturbed<br />

for a while.<br />

2<br />

3<br />

ARTS & LETTERS DHAKA TRIBUNE | THURSDAY, august 3, <strong>2017</strong><br />

DHAKA TRIBUNE | THURSDAY, august 3, <strong>2017</strong><br />

ARTS & LETTERS

Tribute<br />

A sunlit page<br />

Mahmud Rahman<br />

is the author of<br />

the short story<br />

collection, Killing<br />

the Water, published<br />

by Penguin<br />

India. His second<br />

book, Black Ice,<br />

a translation<br />

of Bangladeshi<br />

writer Mahmudul<br />

Haque’s Kalo<br />

Borof, was published<br />

in 2012 by<br />

HarperCollins<br />

India.<br />

He asked some questions to situate me. Once reassured that despite living<br />

abroad, I felt connected to Bangladesh, he opened up. We talked about his<br />

schooldays, his childhood ailments, the houses where he had lived, and his<br />

interest in animals. We touched on his writing and his not writing.<br />

I asked for permission to publish the translation of “Protidin Ekti Rumal.”<br />

He waved his arm in dismissal: I could do as I wished.<br />

Returning home, I sent off the finished story to the Daily Star where it was<br />

published in an Eid Supplement. When I handed him copies, he was delighted.<br />

When I brought up translating more of his writing, he retreated into the<br />

kind of response he had come to be known for: what does it all matter anyway?<br />

In fact, it was his wife, Hosne Ara Mahmud (Kajol) who encouraged me.<br />

She felt strongly the world should know his writing.<br />

I began to visit every two weeks. He would not let me leave for four or five<br />

hours. I had come seeking support for translation, but he gave me much more:<br />

friendship. I sometimes wondered why. I think it was because I never pressed<br />

him on why he did not write. It may also have helped that I was someone exploring<br />

Dhaka’s literary world without hardened attachments and prejudices.<br />

He enjoyed bringing to me a world I did not know.<br />

I chose this novel because it is about Partition.<br />

Lost in our other preoccupations, we often<br />

overlook 1947. But that event played a<br />

momentous role in shaping who we are<br />

Once I finished a draft of my novel, I decided to translate one of his books.<br />

I chose Kalo Borof.<br />

Mahmudul Haque wrote Kalo Borof in a ten-day burst in <strong>August</strong> 1977. The<br />

novel was soon published in an Eid Supplement, but it didn’t come out as a<br />

book until 1992.<br />

I chose this novel because it is about Partition. Lost in our other preoccupations,<br />

we often overlook 1947. But that event played a momentous role in<br />

shaping who we are. Born in its aftermath, I come from a family only tangentially<br />

affected by it. I was familiar with some Partition narratives from writers<br />

who migrated to West Bengal, but I could find few stories of those coming<br />

east. Kalo Borof was the first novel I read that showed the long reach of Partition<br />

into a person’s adulthood in Bangladesh.<br />

The book’s construction also appealed to me. Tightly composed, it is written<br />

in two alternating voices. One voice is intimate, the first person memories<br />

of childhood in Barasat. The other voice is in third person, slightly distanced;<br />

this one depicts Abdul Khaleq’s adult life, his growing alienation, and the<br />

stresses in his married life.<br />

From Ahmad Mostofa Kamal’s interview I also knew this was Mahmudul<br />

Haque’s favourite novel.<br />

Six months after I started to visit, Hosne Ara Mahmud passed away. Stricken<br />

with grief, he moved to Lalbagh.<br />

The tragedy spurred me to get moving with my translation. While working<br />

on it, I put aside phrases that stumped me. Some involved dialect, others were<br />

more of a mystery. I intended to take these puzzles to the author when I had<br />

finished a full draft. Meanwhile during my visits I tried to get as strong a sense<br />

of the novel as I could.<br />

In a few months, I was ready with my list. On July 21, 2008, taking a break<br />

from cooking lunch, I dialled his number to let him know I would be coming<br />

over. A different man’s voice answered. He said that Mahmudul Haque had<br />

died during the night.<br />

The news hit hard. He had often talked about dying, but I paid him little<br />

mind. Though I knew he was in poor health, he had looked fine when I visited.<br />

I never imagined that death would visit this couple so suddenly, one after the<br />

other.<br />

I wrote a tribute to the author and man who befriended me. Then I set<br />

about solving the remaining puzzles from Kalo Borof.<br />

For a translator, an author’s assistance can be immensely helpful. With the<br />

author gone, I had to draw in new resources. I reached out everywhere. Help<br />

with Oriya dialect came from a South Asian literary discussion group on the<br />

internet. Translators and writers I knew helped decode some Bangla dialect. I<br />

was down to one thorny mystery.<br />

In the book, Poka and his friends come across a man who chants, Hambyalay<br />

jambyalay, ghash kyambay khay? What did this mean? No one I asked<br />

knew. The author’s younger brother Nazmul Haque Khoka came to my aid. He<br />

vaguely remembered a saying from West Bengal putting down people from<br />

East Bengal. The words were attributed to Bangals’ supposed confusion upon<br />

encountering an elephant: “A tail out in front, a tail while going, how the heck<br />

does it eat grass?”<br />

The next step was to find a publisher. To gain a wider readership, I wanted<br />

the book published outside Bangladesh. Many excellent translations have<br />

been coming out from India for some time. During a literary festival in Dhaka,<br />

I had met Moyna Mazumdar of Katha, a Delhi based publisher. Eager to support<br />

my project, she connected me to Minakshi Thakur, an editor at Harper-<br />

Collins, and Minakshi carried it the rest of the way.<br />

When we put together the book last year, we included a P.S. section with an<br />

introduction to Mahmudul Haque. This includes excerpts from Kamal’s interview.<br />

Minakshi was a pleasure to work with and with her keen eyes and strong<br />

instincts, she helped clarify and smooth out the final version.<br />

I had failed to get written consent from Mahmudul Haque. In the end,<br />

their children came through. Both Tahmina Mahmud, living in Toronto, and<br />

Shimuel Haque Shirazie, living in Los Angeles, were excited to support the<br />

translation of their father’s work.<br />

With all the pieces in place, HarperCollins released the book in January<br />

2012. It has received mention and reviews in publications in Chennai, Bangalore,<br />

Lahore, Mumbai, and Delhi.<br />

When I visited Barasat, I recalled that Mahmudul Haque himself never<br />

returned as an adult. Once during a trip to Kolkata, he agreed to go, only to<br />

change his mind and ask the car to turn back. He was still haunted with the<br />

pain of departure and preferred his childhood memories intact.<br />

In recalling his life, it is hard to detach the sense of the tragic. The writer<br />

and his wife who I met at the start of this translation journey are gone. Last<br />

year his younger brother also passed away.<br />

But those images of Poka’s childhood in my head are etched deep. The reality<br />

of Hati Pukur did not make them vanish. Mahmudul Haque’s writing remains<br />

alive.<br />

What is the point of repeating lament? When we remember him, is it not<br />

better to celebrate what he gifted? I say, may more readers discover his books.<br />

May those who cannot read Bangla find him in translation. And may more<br />

translations come forth in coming years. •<br />

(This article first appeared in The Daily Star Eid Special issue in 2012)<br />

Pesto and poets:<br />

Landscape of Eugenio Montale’s poetry<br />

• Neeman Sobhan<br />

In May, I visited the rugged, numinous beauty of the Cinque Terre villages<br />

clinging against the serrated Ligurian coastline of the Italian Riviera, draped<br />

like a stone veil of rainbow hued houses sprayed by the glinting Mediterranean<br />

below.<br />

The English Romantics, Byron and Shelley,<br />

had been among the poets who once stayed in<br />

this area giving it the title of “the Gulf of Poets.”<br />

But it was the revenant words of a native poet,<br />

who had spent thirty “distant summers” in<br />

the village of Monterosso, writing about its<br />

“deserted noons,” “occluded valleys” and the<br />

lessons learnt from the “thundering pages” of<br />

the sea, that flit through my mind like seagulls.<br />

This celebrated Italian poet, Eugenio<br />

Montale, who won the 1975 Nobel Prize, came<br />

from Genoa, and like another Genovese,<br />

Cristoforo Colombo, set off on his own<br />

journey, not with seafaring vessels in search of<br />

undiscovered lands but with the seascape of<br />

Liguria as his personal compass, re-charting the<br />

map of contemporary poetry in Italy.<br />

I always love the poetry of nature, of places<br />

and moments intensely felt. I thus love the<br />

early poetry of Montale, which reflects the<br />

mystical connection with the natural landscape<br />

of Liguria. Of course, the Monterosso of today,<br />

and the other villages: Riomaggiore, Corniglia,<br />

Manarola and Vernazza, are not the elemental,<br />

wild land it was during Montale’s youth.<br />

He juxtaposed images that were not always<br />

beautiful, but often harsh and evocative (“that<br />

land of searing sun where the air/ clouds over<br />

with mosquitos”) against the inner world of<br />

his spiritual quest. This led him to the sea (seen sometimes as “the distant<br />

palpitations/of the scales of the ocean,” or, an elusive living creature; and at<br />

other times addressed as “father”) and also the flotsam it washed up like the<br />

bleached bones of the cuttlefish, which became the title of his first poetry<br />

collection.<br />

From the train station at Monterosso’s beach, we walk up the path<br />

overlooking the bay, and enter the walls of the town. At lunch in a courtyard<br />

of oleanders and lemon trees, we rave about the fresh Pesto that Liguria is<br />

famous for: That poetic paste of fragrant basil leaves, garlic, pine nuts, olive<br />

oil and parmigiano cheese.<br />

Later, as we sip Sorbetto al limone, I think of Montale’s famous lines:<br />

“… here even we, the poorest, find a fortune/ and it is the scent of lemons…..”<br />

Montale, however, was not poor. His family owned a summer home here.<br />

That villa, unfortunately, is not open to the public, but there is a “Literary<br />

Park” for visitors to take guided walks through the terraces leading down to<br />

the sea to enjoy the vistas that inspired the poet.<br />

We don’t have time for this, so I content myself with rereading one of his<br />

famous poems from his first published volume “Ossi di Seppia” (Cuttlefish<br />

Bones) from 1925. The title “Meriggiare,” shows how a poet can make a verb<br />

out of a time of the day: ‘meriggio’ meaning mid-day. It’s past noon, and the<br />

verb implies exactly what I am doing just now: whiling away the torpid hours,<br />

just reflecting on the world.<br />

Montale had trained to be a singer, so the complexities and discordant<br />

aspects of music and language, of consonance and assonance, and not just the<br />

melodic and lyrical nature of word and sound, played a huge part in the way<br />

Montale employed his poetic language. He created a counter-eloquence to the<br />

lushness of Italian poetry that was dominated by the incantatory lyricism of<br />

Gabriele D’Annunzio.<br />

In this early poem we can taste what Montale<br />

created: Astringency not unlike the lemon and<br />

sea salt and pesto of his landscape, producing,<br />

despite the structured rhymes and metres,<br />

something untamed and gritty, both in the hard<br />

sounding words, and in the harsh beauty of his<br />

unpredictable images.<br />

Having enjoyed the original, I wished my<br />

readers could hear the deliberate choppiness<br />

and the many onomatopoeic sounds of the<br />

Italian. I compared the many translations<br />

done by scholars of Montale, like Arrowsmith,<br />

Galassi, Archer, Young and Bell, I was still<br />

dissatisfied, and created my own version.<br />

Still, my translation here of the first verse of<br />

‘Meriggiare’ merely sketches the meaning of<br />

what the original paints in aural and visual<br />

colour.<br />

Meriggiare pallido e assorto<br />

/presso un rovente muro d’orto,<br />

ascoltare tra i pruni e gli sterpi/<br />

schiocchi di merli, frusci di serpi.<br />

Whiling away the noon, pale and scattered<br />

beside the scorching walls of an orchard,<br />

listening among the dry bush of brambles<br />

the blackbird’s croak, the snake’s dry rustle...<br />

The rest of the poem describes a summer’s day loud with the jagged<br />

screech of cicadas, spent watching red ants file through cracks in the dry<br />

earth, and glimpsing afar a heaving sea holding out illusions of liberty. It’s a<br />

world suspended between despair and negation on the one hand, and a desire<br />

for transcendence and hope on the other. It ends with Montale’s vision of the<br />

human condition in a world that’s both a prison and a refuge from Fascism<br />

and the looming of the two world wars: A life protected by “una muraglia/che<br />

ha in cima cocci aguzzi di bottiglia,” or a boundary wall topped with shards of<br />

broken bottles.<br />

Around me the sunlight is waning. From balconies potted geraniums and<br />

laundry wave. It’s time to leave charming Monterosso. A waiter brings to a<br />

nearby table a pizza, slathered green with pesto – the colour of new life. I<br />

ponder Montale’s latter poetry that was negative in tone. How can anyone be<br />

despondent in this place?<br />

He whispers to me:<br />

Maybe only those who want to, become infinite,<br />

And, who knows, you can do it; I cannot.<br />

I think Montale did manage to embrace infinity with his immortal poetry.<br />

“Like that circle of cliffs/that seems to unwind/into spider web of clouds,/<br />

so our scorched spirits/in which illusion burns/a fire full of ash<br />

are lost in the clear sky/of a single certainty: the light.”•<br />

Neeman Sobhan is<br />

a writer, poet and<br />

columnist. She lives<br />

in Italy and teaches<br />

at the University<br />

of Rome. Her<br />

published works<br />

include a collection<br />

of her columns,<br />

An Abiding City:<br />

Ruminations<br />

from Rome (UPL);<br />

an anthology<br />

of short stories,<br />

Piazza Bangladesh<br />

(Bengal<br />

Publications);<br />

a collection of<br />

poems, Calligraphy<br />

of Wet Leaves<br />

(Bengal Lights).<br />

4<br />

5<br />

ARTS & LETTERS DHAKA TRIBUNE | THURSDAY, august 3, <strong>2017</strong><br />

DHAKA TRIBUNE | THURSDAY, august 3, <strong>2017</strong><br />

ARTS & LETTERS

Tribute<br />

Ancient Bengali literature<br />

Tantra and Bangla folk literature<br />

• Azfar Aziz<br />

Rifat Munim is<br />

Literary Editor,<br />

Dhaka Tribune..<br />

Sudhin Das:<br />

A life in Nazrul’s songs<br />

The artist who spent most of his life<br />

collectiong authentic notations of<br />

Nazrul songs passed away aged 87 on<br />

June 27<br />

• Rifat Munim<br />

Sudhin Das, who spent most of his life preserving and practising Nazrul<br />

songs, lived in seclusion in the last ten years or so of his life. The only<br />

time he was seen in public was when he was honoured or given awards<br />

at various cultural functions. But his commitment to the shuddha or<br />

pure form of Nazrul songs did not always allow him the seclusion he desired. In<br />

spite of himself, he had to busy himself at times, teaching, or singing for radio<br />

or television channels, or sometimes, supervising recordings of Nazrul songs.<br />

In one auspicious afternoon sometime in <strong>August</strong> 2010, I had sought him out<br />

at his house in Mirpur. As I entered his flat, I found him surrounded by a cluster<br />

of keen young students. He was giving them the last lesson.<br />

Over the span of his 60-year-long career as a singer and music expert,<br />

I thought, he has carved his name in the history of Bangla music as the one<br />

who’s initiated the work of collecting the original notations (Swaralipi) of Nazrul’s<br />

songs, based on various reliable sources – a work left unfinished by the<br />

creator himself, the legendary literary as well as musical genius, Kazi Nazrul<br />

Everyone calls me an expert, but I know<br />

nothing about Nazrul songs because the<br />

overall range of his songs, in terms of<br />

figurative interpretation, is too vast for<br />

anyone to grasp<br />

Islam. He, however, didn’t look particularly happy when he was referred to as<br />

an expert in Nazrul songs. “Everyone calls me an expert, but I know nothing<br />

about Nazrul songs because the overall range of his songs, in terms of figurative<br />

interpretation, is too vast for anyone to grasp.”<br />

Known mostly as a Nazrul exponent, he’d devoted himself to Bangla songs.<br />

Born in 1930 in Comilla, Sudhin had begun his singing career in the late 1940s<br />

for Radio Pakistan Dhaka, which was in old Dhaka, at a time when there was<br />

no television and the budding singers had to depend on the radio. But I was<br />

surprised to learn the celebrated expert on Nazrul’s music had begun his career<br />

with Tagore songs. “Not only at the beginning but I have sung Tagore songs<br />

alongside Nazrul’s and other genres of modem songs throughout my life. It<br />

was with a Tagore song that I finished off my long singing career at Bangladesh<br />

Betar ten years ago,” Sudhin recalled.<br />

He’d also worked extensively on songs of other major poets known as the<br />

“Pancha Kabi,” a group of five poets writing and composing their own songs,<br />

mostly in the first half of the 20th century. In other words, the Pancha Kabi laid<br />

the foundation of modem Bangla songs. Apart from Rabindranath Tagore and<br />

Kazi Nazrul Islam, the group included Rajanikanth Sen, Dwijendralal Ray and<br />

Atulprasad Sen.<br />

The folk tradition in Bangla music had also caught Sudhin’s eye and he<br />

composed the Swaralipi of a good number of Lalon songs too. This piece of<br />

information made me curious about why a person so well versed in almost all<br />

genres of modern and folk songs, spent most of his time collecting authentic<br />

notations of Nazrul songs and researching various aspects of his compositions,<br />

when everyone else was busy bringing out albums, or boosting their career by<br />

taking other intitiatives. “An unpleasant revelation made me focus on Nazrul<br />

songs. While I was engrossed in Pancha Kabi, I was astonished to see that songs<br />

of the other major poets, except Nazrul, were more or less preserved. For ex<strong>amp</strong>le,<br />

Tagore’s songs, which, like his fictions and poems, are well preserved.<br />

Nazrul’s songs, on the other hand, always suffered distortion at the hands of<br />

others,” Sudhin explained.<br />

When he was working on Bangla music in general, he discovered that Nazrul’s<br />

songs outnumber all other major poets and lyricists, surpassing 3,000<br />

roughly. Not only that, he also realised that Nazrul’s songs, especially authentic<br />

notation of his songs, had remained largely unguarded as the poet in his<br />

lifetime could not finish that work.<br />

Tagore composed more than 2,000 songs and provided specific notations to<br />

them, all of which were published by Visva Bharati and protected by copyright.<br />

“Tagore’s long literary career spanning nearly 70 years also helped him<br />

spend as much time as was necessary to compose the notations,” Sudhin went<br />

on explaining. “Nazrul’s creative life, on the other hand, had spanned only 20<br />

years and even during that he was actively involved in political activism and<br />

literary movements. Apart from an unsurpassable number of songs, he wrote<br />

poems, novels, short stories, essays and plays. Added to this was his personal<br />

loss and financial strains. It was barely possible for a creative man to keep pace<br />

with all these and get notations published at the same time.”<br />

The rest of Das’ life in terms of musical accomplishments was intertwined<br />

with the history of how original notations of Nazrul songs were authenticated<br />

over the years.•<br />

(Read the full article here: http://www.dhakatribune.com/articles/magazine/<br />

arts-letters/)<br />

In our contemporary vernacular use, “Tantra” is often used as a suffix<br />

meaning “ism”, government/political system, or philosophical/ideological<br />

school, for ex<strong>amp</strong>le, monarchy is Raj-tantra, democracy is Gana-tantra,<br />

and individualism is Sva-tantra. But when we use the word in the<br />

arena of religion or spiritual practices, it stinks awfully – mainly of sexual<br />

excesses and sometimes even of black magic. Yet a great body of literature<br />

in Bangla ranging from the thousand-year-old Charyagiti down to R<strong>amp</strong>rasad<br />

Sen-Lalon Fakir-Bhaba Pagla to the contemporary mystic singers and folk poets<br />

is heavily influenced by Tantra. The urban classes may have forgotten the<br />

creed, but the folk writers and singers still treasure the (probably pre-historic)<br />

heritage of Tantra.<br />

That the word Tantra means an esoteric practice or religious ritualism, according<br />

to a number of Indologists, is a colonial-era European invention (Padoux<br />

2002, White 2005, Gray 2016). It was so perhaps because of the colonialists’<br />

memory of the practices of the Dionysian cult. The negative connotations<br />

that Tantra acquired even in the Indian Sub-continent about its association<br />

with sex and magic are triggered mainly by an exaggerated and ignorant perception<br />

caused by people’s negative attitudes towards sex and sexuality as a<br />

Tantra meditation<br />

result of its prolonged suppression in society under all the major religions. guide or knowledge in any field that applies to many elements (Douglas Renfrew<br />

Brooks, 1990).<br />

The two cardinal reasons for the mass-misconception about Tantra are the<br />

heavily publicised erotic cave sculptures at Khajuraho and the metaphoric So the primary reason for misconstruing Tantra is the sexually repressed<br />

language of the Charyapada that often alludes to sexual union or lovemaking. mass-consciousness. But Tantra is not based on sex but on sexual energy, of<br />

According to Wikipaedia, the Khajuraho temples, primarily devoted to Shiva<br />

and built between 970 AD and 1030 AD, “...have a rich display of intricately man being has two hemispheres in his brain – right and left. The right brain<br />

controlling and using it to perfect one’s own self. It’s no secret that every hu-<br />

carved statues. While they are famous for their erotic sculpture, sexual themes that controls the left side of the body is emotional, imaginative, empathic,<br />

cover less than 10% of the temple sculpture. Further, most erotic scene panels intuitive, creative, and giving – the dominant character traits of women, while<br />

are neither prominent nor emphasized at the expense of the rest; rather they the left brain that controls the other side of the body is masculine in characteristics<br />

and shows the traits of reason, calculation, ideation, planning, ruthless-<br />

are in proportional balance with the non-sexual images. The viewer has to<br />

look closely to find them, or be directed by a guide. The arts cover numerous ness, possessiveness, etc. In every individual, one of the hemispheres plays<br />

aspects of human life and values considered important in Hindu pantheon.” the dominant role and thus determines his/her gender role, while the other<br />

As for the Charyapadas, they are the works of a group of Yogic and Tantric half remains mostly dormant. While morphing its way to the current configuration,<br />

the human species somehow figured out that if the two poles of its<br />

masters belonging to the Buddhist Vajrayana sect and probably also to the<br />

Shaivite sub-sect called Nath S<strong>amp</strong>radaya. The Charyapadas are written in gender roles can be fused, it can become more wholesome, do things much<br />

a twilight (metaphoric) language and so are mostly misunderstood. People better and be happier than ever. In our time, this conclusion has been echoed<br />

tend to forget that Tantra, which is much older than Buddhism, should not by Carl Gustaf Jung in Liber Novus: “But if you pay close attention, you will<br />

be judged by the alleged excesses practised by members of a mere sub-sect of see that the most masculine man has a feminine soul, and the most feminine<br />

Mahayana Buddhism.<br />

woman has a masculine soul.” Prof María Carolina Concha, a psychotherapist<br />

Tantra literally means “loom, warp, weave.” The Sanskrit root “tan” means and a follower of Jung, says: The “soul” that accumulates in the ego’s consciousness<br />

during the opus has a feminine character in the male and a mascu-<br />

the warping of threads on a loom. It implies “interweaving of traditions and<br />

teachings as threads” into a text, technique or practice. As a system of esoteric line in the female. The soul [anima] wants to reconcile and unite; the animus<br />

spiritual practice, Tantra predates even the earliest of Vedas. The word appears<br />

in the hymns of the Rigveda with the meaning of “warp” (weaving). It is Therefore, the word “Tantra” stands for the very process of merging an in-<br />

tries to discern and discriminate.<br />

found in other Vedic-era texts like the Atharvaveda and many Brahmanas. In dividual’s masculine and feminine selves into a complete whole. One then becomes<br />

really Sva-tantra, independent. So the Dombi with whom Kahnupada<br />

Vedic and post-Vedic texts, the contextual meaning of Tantra is that which<br />

is “principal or essential part, main point, model, framework, feature”. In makes love in his “Charya 10” is his own feminine self. It’s the boat on which<br />

the Smritis and epics of Hinduism (and Jainism), the term means “doctrine, the boatman makes his reverse journey; and it’s depicted in the statue of the<br />

rule, theory, method, technique or chapter” and the word appears both as a half-man-half-woman deity called Ardhanarisvara.<br />

separate word and as a common suffix, such as atma-tantra meaning “doctrine<br />

or theory of Atman (soul, self)” (Sir Monier Monier-Williams et al, 2002). whole human, but suffice it to say here that the mystics in the Eastern hem-<br />

We will not delve much into the particulars of the process of becoming a<br />

As the number of Tantra’s definitions is as large as there are religious cults isphere of the globe have known for long that “Whatever is there in the cosmos<br />

are in this body, too.” A human being first makes himself whole and then<br />

and philosophical schools in the world, I’d put an end to defining Tantra by<br />

quoting two masters who really deserve to be cited. The great grammarian continues to seek the “man of the mind” (Moner Manush), as do the Bauls. In<br />

Panini (5th century BCE) explains Tantra through the ex<strong>amp</strong>le of “Sva-tantra” the West, the motto is phrased as “As Above So Below” and the fusion of inner<br />

which, he states, means “independent” or a person who is his own “warp, man with inner woman is called the Inner Alchemy. Tantra and Inner Alchemy<br />

cloth, weaver, promoter, karta (actor).” Patanjali, the grandmaster of yoga, need a ladder (the spine, the Jakob’s Ladder mentioned in the Bible) to climb<br />

quotes and accepts Panini’s definition. He says the metaphorical definition from the naval, where the sun aka feminine vitality resides, up to the crown of<br />

of Tantra as “warp (weaving), extended cloth” is relevant to many contexts, the head, where the moon/masculine/nectar is. If this is a religion, well Yoga<br />

adding that it also means “principal, main”. Patanjali also offers this semantic too then is a religion; if this is spiritual, psychotherapy too is spiritual; if this is<br />

definition of Tantra – it is structural rules, standard procedures, centralized sexual excess, then a flower too is so.•<br />

Azfar Aziz<br />

is a Dhakabased<br />

freelance<br />

journalist,<br />

writer and poet.<br />

6<br />

7<br />

ARTS & LETTERS DHAKA TRIBUNE | THURSDAY, august 3, <strong>2017</strong><br />

DHAKA TRIBUNE | THURSDAY, august 3, <strong>2017</strong><br />

ARTS & LETTERS

Film criticism<br />

How 300 erases aspects of<br />

Sparta’s history<br />

A step into the future<br />

Doctor Who’s female reincarnation is something we should all be excited about<br />

Film criticism<br />

• Shuprova Tasneem<br />

Zarin Rafiuddin<br />

reviews books<br />

and movies for<br />

<strong>Arts</strong> & <strong>Letters</strong>.<br />

• Zarin Rafiuddin<br />

What strikes one first about 300, a Zack Snyder 2006 American film, is that it is<br />

a big display of machismo. All of the characters in the entourage of Leonidas,<br />

the Spartan king, are chiselled, muscular men with washboard abs and burly<br />

limbs. The film apparently is a tribute to the heroic efforts of a select group<br />

of Spartan soldiers repulsing an invading Persian army. It is set in an ancient<br />

atmosphere with a scroll-like sepia tone that washes the background and<br />

the characters alike. This is further accentuated with the people of Persian<br />

descent who are shown to be dressed in vibrant colours. Adapted from Frank<br />

Miller’s graphic novel of the same name, the film dramatises a historical event<br />

which had actually transpired. There is only one problem: It did not happen<br />

that way.<br />

Yes, 300 is based on a distorted account of what had happened during a<br />

war between the Persians and the Spartans. A group of 300 Spartans had not<br />

defeated the Persians; it was just the other way around.<br />

Sparta, despite its draconian laws and chauvinistic culture, had failed to<br />

beat the Persian army with a band of its 300 men. They were surrounded<br />

by Persian soldiers and had to call for backup, which unfortunately never<br />

ariived. The battle with the 300 Spartan soldiers was called the Battle of<br />

Thermopylae and it put a big dent on Spartan society. It was a huge blow to a<br />

culture which thrived on jingoism and which trained male youths to adopt a<br />

soldier’s lifestyle. These aspects are portrayed in Spartan, a novel written by<br />

Valerio Massimo Manfredi. Though Manfredi isn’t necessarily sympathetic to<br />

the Persians, he does show what the Battle of Thermopylae really was for the<br />

Spartans: A mortifying defeat to the Persians.<br />

The story in Manfredi’s book revolves around Talos, who is living with his<br />

adoptive family, the Helots. Talos is actually a son of a noble Spartan who<br />

was abandoned to die by his reluctant father as he was born with a limp.<br />

The Helots were a people enslaved by the Spartans but 300 doesn’t mention<br />

them at all. Talos does not like Spartan arrogance and their ill-treatment of<br />

his adoptive family and their kin. The very first meeting that Talos has with<br />

his biological brother, Brithos, is when he is harassing the woman Talos loves.<br />

This exchange ends with Talos fighting Brithos and his friends until he is<br />

overpowered and severely wounded. Antinea is a Helot girl who the Spartan<br />

youth felt privileged enough to harass and molest. Talos also bemoans to<br />

Antinea that a slave’s life is a wretched one and that gaining pride and honour<br />

is a privilege exclusive to the Spartans.<br />

The novel overlaps with 300 in that Ephialtes is shown to defect to the<br />

Persian side and help the Persians win the Battle of Thermopylae. Ephialtes<br />

is the man with disabilities in the film; he implores Leonides to induct him<br />

in the army but Leonides rejects him. In the novel, he is just a typical Spartan<br />

warrior who has defected. However, Ephialtes is not deformed in Manfredi’s<br />

story and is killed by a friend of Talos. Brithos’s honour is completely at<br />

stake after the Battle of Thermopylae. He was sent by King Leonidas with a<br />

letter requesting immediate reinforcements, which was replaced along the<br />

way with a blank sheet. Now People believe he and his friends are deserters.<br />

Aghias, one of Brithos’s friends, commits suicide when an old friend refuses<br />

to share their fire with him to light his house as he believes Aghias is a traitor.<br />

Brithos alone then carries Aghias for his funeral; no one else has joined the<br />

funeral procession. Brithos is disowned by his own society for these events<br />

and it is then Talos decides to help him out. They form a companionship and<br />

plan to drive out the Persians and regain Brithos’s honour, though, the gap of<br />

class remains. As Talos says to Brithos with conviction: “No, Brithos, don’t tell<br />

me that fate has made us slaves, that the gods have given you power over us.”<br />

(Manfredi 208)<br />

Ultimately, even when Talos is reinstated into the Spartan society, and<br />

gains back his actual birth name, Kleidemos, he chooses to fight a war against<br />

the Spartans to free the Helots from slavery. Kleidemos fights a war against<br />

Leonidas’s son, Pleistarchus, to liberate the Helots saying that Leonidas also<br />

recognised the bravery and dignity of the Helots. In the battle of Thermopylae,<br />

Leonidas saw Helot soldiers fight bravely and as equals with the Spartans and<br />

realised Sparta should be one nation. He conveyed this in the letter handed to<br />

Brithos who lost it on his way back. The letter is the reason why Brithos and<br />

a select group of men left Thermopylae in the first place. Whether this is true<br />

of Leonidas or not can be contested. Manfredi, however, does not glorify the<br />

Spartan race as the film 300 does. The novel is clearly against slavery of people<br />

whether it is done by the Spartans or the Persians.<br />

The film 300 excludes the socio-political history of the Spartans altogether.<br />

It excludes the Helots and demonises the Persians. By endowing the Persians<br />

with demonic physical features, showing Xerxes, the Persian king, as a giant<br />

with feminine traits, it makes a mockery of the complex histories of the two<br />

nations. Xerxes is also present in Mandfredi’s novel and his attack on Sparta is<br />

a political one. He admits of not having known any Spartans when he meets<br />

one of the Spartan kings, Demaratus; he expresses his desire to conquer the<br />

Grecian lands partly as retribution on Athenians who aided the Ionian rebel<br />

group against his men. The book makes good use of this bit of history rather<br />

than showing Xerxes in his love den, cuddling half-naked women and asking<br />

them to seduce Ephialtes, as the film 300 depicts. Manfredi’s book presents,<br />

realistically, a king with enemies, and declaring war against them.<br />

The film 300 is built upon a distorted story of murder, mystery and sex<br />

that gives history, once again, a Western twist, making it palatable for Western<br />

tastes. It erases those parts of Spartan behaviour that do not go with the lofty<br />

democratic ideals of the West, parts that would actually make them look like a<br />

lot more regressive than their Asian counterparts. It does not show the slaves<br />

alongside their rulers who are treating the Helots with contempt, forcing<br />

them to do menial labour so that they can enjoy the privilege to act heroic and<br />

fight their wars. To deny the equality of a race is a crime that the Spartans did<br />

commit. Whether or not the Spartans are brave is not the issue here, but that<br />

they failed to mention the Helots fighting alongside them is.<br />

300 has erased that bit of history completely. •<br />

“Every story ever told really happened. Stories are where memories go when<br />

they’re forgotten.” - Doctor Who<br />

Stories are important. In the end, they’re all we have, and as we grow up,<br />

the stories we learn are eventually what make us who we are, and create the<br />

social norms we live in. And in this day and age, there’s no denying that the<br />

stories on TV have a huge impact.<br />

Given the general drivel that tends to pour out of the magic box, I cannot<br />

help but celebrate that we have entered the age of the geeks - an era of<br />

television (mostly in English) that has finally left off the mediocre sitcoms and<br />

run-of-the-mill romances and focused on telling proper, fleshed-out stories,<br />

usually adapted from novels and comic books, or having roots in fantasy or<br />

science fiction.<br />

Thankfully, this is also the age of greater representation - media is slowly<br />

being saturated with characters and actors from diverse backgrounds,<br />

and getting rid of tired old gender roles. As the success of Rey, the female<br />

protagonist from Star Wars: The Force Awakens, and more recently that of<br />

Wonder Woman shows, the future generations are more than on board with<br />

the idea of heroes who aren’t white males.<br />

Representation is important<br />

When I was a little girl, I desperately wanted to be Kakababu, the disabled<br />

detective created in the incredible mind of Sunil Gangopadhyay, or Simba,<br />

the protagonist in Disney’s The Lion King. When you’re that young, gender (or<br />

species, for that matter) is not a construct that matters to you. But as I grew<br />

older, I learnt that it would be impossible for me to one day turn into a lion<br />

and become the king of Pride Rock. I also learnt that I couldn’t be Kakababu,<br />

because I was a girl.<br />

It’s interesting what you get socialised into believing, without really<br />

realising it. There should be no limits to a child’s imagination, but the sad<br />

truth is that we place those limits and we learn them by heart - and one day<br />

we turn on the television hoping to find a character we can relate to, and if<br />

you’re a little girl from Bangladesh - chances are you won’t find too many. And<br />

whether you idolise Batman or Mashrafe, I can guarantee that the barrier of<br />

sex soon becomes an unscalable one for many girls.<br />

That is why it’s so important to see women in lead roles from a young age -<br />

not just to let girls dream big, but to show girls and boys that gender really is<br />

a social construct. Of course, there is something to say about tokenism here<br />

- there’s no point in having a woman or ethnic minority for the sake of it, or<br />

switching from James to Jane Bond, without giving them stories of their own<br />

that actually engage the audience.<br />

Which is why no one is happier than I am that the family-friendly, British<br />

sci-fi show Doctor Who has decided to make history by choosing its first ever<br />

female lead to play the Doctor.<br />

No plan, no weapons and nothing to lose<br />

Just for a little context - Doctor Who first aired on the BBC in 1963 and features<br />

the Doctor, a time-travelling genius from an alien race called the Time Lords<br />

who have the unique ability to regenerate rather than die. The classic series<br />

ran till 1989, but a hugely popular reboot in 2005 has now seen it reach cult<br />

status and go worldwide. So far, 12 male actors have played the role of the<br />

Doctor, all with their own interpretations, and Jodie Whittaker will be the first<br />

female to take on the role.<br />

Science-fiction’s ability to transform is why it is one of my favourite genres -<br />

for decades, sci-fi has paved the way to the future, ranging from light-hearted<br />

futuristic adventures to deeply philosophical contemplations of the human<br />

condition that can often be way ahead of its time. The best thing about Doctor<br />

Jodie Whittaker<br />

Who is that this sci-fi show is both.<br />

I am definitely sentimental, but in a world filled with violence, I can think<br />

of no better role model than the Doctor - an impossible hero who uses his<br />

superior intellect and charming wit to save the day, while subtly preaching<br />

an anti-war message filtered with an undying belief in humanity, hope and<br />

kindness.<br />

The most recent run, with Peter Capaldi as the twelfth Doctor, has been<br />

lauded not only for its casting - featuring disabled, LGBT and racially diverse<br />

characters - but its messages against racism, capitalism and toxic masculinity.<br />

Given that most of the heroes that children see on TV nowadays, whether in<br />

cartoons or movie adaptations of comic books - tend to use their weapons or<br />

superpowers to fight the bad guys, I can’t stress enough on how important<br />

it is to have a hero who simply uses his brains, stays strong in his belief in<br />

nonviolence, and still manages to stay relevant in the modern era.<br />

The backlash is exactly why we need a female Doctor<br />

The latest story arc in Doctor Who already saw another Time Lord transform<br />

from the Master to Missy and was hugely popular. One of the original cocreators<br />

of the show, Sydney Newman, began lobbying for a female Doctor<br />

back in the mid-eighties.<br />

The show has referred multiple times to gender being a non-issue for<br />

the Time Lords - so the vitriol pouring out from fans and media after the<br />

announcement of a female Doctor has been shocking, to say the least. It’s<br />

strange when you think about it - a story about an alien who can travel in a<br />

box through time and space and regenerate his entire body is acceptable, but<br />

his transformation into a woman isn’t.<br />

Whether it was the “will her spaceship become a kitchen?” jokes or the slutshaming<br />

of the actress by British tabloids - who jumped at the opportunity to<br />

print nude photos of Jodie Whittaker in a display of text-book misogyny - the<br />

downright anger and disbelief aimed at the show is once again proof of sci-fi’s<br />

ability to shock and push us into widening our horizons and challenging the<br />

status quo.<br />

This is exactly why we need a female Doctor. My mother grew up with<br />

women who were usually the damsels in distress, heroines with the long lashes<br />

and limited lines. I grew up with women who were increasingly stronger and<br />

braver, who could fire guns, build war machines and generally kick ass. But<br />

now that I’m older, I long for my niece to have heroes who solve problems, help<br />

people and alongside being cool, are brilliant, intelligent, forgiving and kind.<br />

Thanks to Doctor Who, now she can not only have this hero, but have<br />

him/her in a mould that doesn’t adhere to traditional gender roles. Maybe,<br />

just maybe, she will end up in a world where children can be whatever they<br />

imagine they want to be, without taking anyone’s gender, race or sexual<br />

orientation into account.<br />

Now that’s a sci-fi future I can definitely get on board with. •<br />

Shuprova<br />

Tasneem is Deputy<br />

Magazine Editor,<br />

Dhaka Tribune.<br />

8<br />

9<br />

ARTS & LETTERS DHAKA TRIBUNE | THURSDAY, august 3, <strong>2017</strong><br />

DHAKA TRIBUNE | THURSDAY, august 3, <strong>2017</strong><br />

ARTS & LETTERS

Remembrance<br />

Bengali poetry in translation<br />

Abul Hasan<br />

From Mahadev’s place<br />

Dear Goon,<br />

After witnessing quite a brawl between Al Mahmud and Mahadev Saha, I<br />

came over to Mahadev’s place and there I found a letter that you’d written<br />

to him. I read the letter again and again. On one hand, I felt elated to have<br />

enjoyed your company through the letter and on the other, I felt wounded<br />

thinking you hadn’t written any letter to me even though you always knew<br />

my address. I don’t know why but I have always found myself enquiring<br />

after you, though you never bothered to write to me – maybe I was goaded<br />

on by the pain of your absence. What other reason could there be for me<br />

to enquire about you? There was a time when you wrote to me on yellow<br />

postcards; in those days even when you were far away it seemed to me like<br />

you were always there, present with a brightness that none could overlook ...<br />

True that the paths where our life intersected are far behind us, and<br />

the bridges built on them are shattered. Even then, isn’t there anything left<br />

of those intense days that we spent together, that which might shake your<br />

memory just for a bit? Couldn’t I also have received a letter courtesy of those<br />

memories? I admit that some of my flaws and weaknesses have pushed us<br />

away from each other. At the beginning you loved what I didn’t: Liquor,<br />

prostitute, marijuana and hashish. But when you quit them and it was time<br />

for us to come closer to each other, maybe it was fate or I don’t know why, we<br />

became isolated from each other instead. The isolation perhaps was caused<br />

by my incurable disease.<br />

I’ve become a different man after returning from Berlin. So, every time<br />

I tried to restore those shattered bridges between us, my health revolted.<br />

Things that you love my body can’t take, but mainly because I’m sick. But<br />

the relationship that my inner self has with yours, that relationship which<br />

only a poet can have with another poet, I have always treasured that.<br />

I met you after <strong>August</strong> 15, but later I came to know you left Dhaka already.<br />

That you left Dhaka deeply saddened me; it also stung me for the impending<br />

loneliness. First I thought you’d gone home just as you often did and would<br />

come back eventually. Later I came to know you’d gone for quite a while.<br />

You’ve written to many friends and acquaintances, and it is from them I<br />

have learned all this. I too was waiting that I’d receive a letter, but waiting<br />

does not always bear fruits.<br />

Your letter to Mahadev I have read again and again. It was worth reading<br />

repeatedly. The sadness and loneliness that usually pervade letters written<br />

by poets – screams of that feeling did make me lonely for some time. I too<br />

needed this loneliness. It has been a long time since I was so beautifully lonely<br />

as this. In fact, this loneliness was what I’d been looking for in the company<br />

of friends ever since I returned from Berlin. The woman I’s spending time<br />

with to get some sense of this loneliness, she cannot provide me with it either.<br />

Perhaps you are the only person who gave me this loneliness for a long<br />

time. Have you forgotten those days altogether – when in the fog of winter,<br />

ignoring the chilling midnight wave, we had explored the numerous alleys<br />

of Dhaka. Weren’t we very happy back then? Can’t you return for the sake<br />

of that happiness? No matter how much our shadows pursue love, you and I<br />

both know that we were lovers to each other. And only men can preserve the<br />

memory of love because women are too transient. And only men can accept<br />

the feeling of sadness emanating from that transience. We were bonded<br />

by an oath of that transience. That feeling, that love is the only cherished<br />

memory in my life, though I don’t know how valuable it is for you today.<br />

Take my love. Stay well and come back.<br />

Wish you all the best,<br />

Nirmalendu<br />

Goon is one of<br />

Bangladesh’s<br />

biggest and most<br />

popular poets.<br />

O friend of mine<br />

• Nirmalendu Goon<br />

I knew Abul Hasan was very fond of his mother and sister. He liked Buri very<br />

much. Talking about his family, he spoke only of his mother and sister; he<br />

barely mentioned his father and brothers. His mother and sister, ever since<br />

they came to Dhaka from the village, were always there by the side of his<br />

sickbed. His mother knew that he’d visited my ancestral village home but I<br />

never visited his. Hasan was not very keen on visiting his own village home.<br />

Since he returned from Berlin, he hadn’t gone back home, not for once ...<br />

I always kept with me the two letters that Mahadev and Hasan had written<br />

me jointly. When I was incarcerated in the Ramna prison and had difficulty<br />

sleeping at night, I read those letters to while away time. I read them frequently,<br />

and I liked doing it. Some of my prison mates thought I was poring over letters<br />

sent by my beloved. The truth is I did consider them as love letters. Those<br />

letters, filled with friends’ love and anxiety, comforted me at the time when<br />

my days were all pale and bleak; they spurred me on to live.<br />

When Hasan’s health deteriorated instead of improving, Hasan’s letter<br />

turned out to be more important to me. I sat up to read Hasan’s letter again in<br />

the dead of night. What did he want to say in the letter? Why was he so hurt<br />

to not receive a letter from someone as unimportant as me? I started feeling<br />

guilty. Though he had written to others from Berlin, he’d never written to me.<br />

Right after the brutal killing of <strong>August</strong> 15, when I was too shocked to be alone,<br />

one afternoon I saw Hasan going somewhere on a rickshaw; he was with<br />

Suraiya Khanum. I called him out and our eyes met but he chose not to stop.<br />

I began reading Hasan’s letter again:<br />

I don’t break down easily. I had lost my mother in childhood; I hadn’t<br />

cried. When elder brother left for India forever, I didn’t cry either. I don’t cry<br />

easily. Tears wouldn’t come to my eyes but I really felt like crying after reading<br />

Hasan’s letter. I cried in my mind.<br />

<br />

(Translated by <strong>Arts</strong> & <strong>Letters</strong> Desk)<br />

Hasan.<br />

[Sachitra Sandhani, 1st Year, Issue 31, Sunday, 26 November 1978]<br />

As I won’t come back<br />

Al Mahmud<br />

As I won’t come back I’m staring down at a spoonful of cream scooped out<br />

From the layer floating on milk. On the outside a haze of rain<br />

Has laid out over the earth, as if, a white sheet woven with dreams.<br />

Why does the heart agitate so much? Because I won’t come back ever?<br />

My hands are shaking yet out of some habit I’m jotting down<br />

Whatever names of people or things I could think of.<br />

At the end of every name I wrote, I won’t come back.<br />

Birds, I won’t come back.<br />

Rivers, I won’t come back.<br />

Women, I won’t come back, my sisters.<br />

As I won’t come back I take the first flag in the procession<br />

In my hand.<br />

As I won’t come back<br />

I organise the men within men.<br />

Why else weave words within words?<br />

I won’t come back, that’s why.<br />

Why keep another chest within the chest?<br />

I won’t come back, that’s why.<br />

Still, beneath memories is piled up, layer after layer, the opaque water<br />

Of sadness. It seems like the river that I’ve known so well<br />

Is not a river after all;<br />

it’s just some flow of water through intimations and signs.<br />

The woman who’s untied her petticoat on being licked and cuddled wildly<br />

Have I sighted the nudity of her back in full?<br />

Maybe near her thigh there was a sepia mole,<br />

And my fiery tongue didn’t even notice,<br />

Intoxicated as it was with desire!<br />

Today sitting beside my insatiate heart,<br />

On this melancholic kerchief who are you writing<br />

In black letters, “I won’t come back?”<br />

Happiness, I won’t come back.<br />

Sorrow, I won’t come back.<br />

Love, O lust, O my poetry<br />

Are you all just mileposts<br />

On the road that no one takes to come back home?<br />

(Translated from Bengali by <strong>Arts</strong> & <strong>Letters</strong> Desk)<br />

Love in the rain<br />

Abul Hasan<br />

Do you recall it had rained once?<br />

Once rain had come down to settle here like a train<br />

At our station the raindrops, like robbers, were quite a nuisance all day;<br />

Like petty politicians they chanted profound slogans<br />

From neighbourhood to neighbourhood.<br />

Yet we didn’t wade through the mud to attend the meeting.<br />

Theatre got cancelled, people in this rain<br />

Got back home from both card games and rallies;<br />

Trade was in a real mess, beset by damage and loss,<br />

The ruckus caused by those slogans all day long<br />

Demanding this person be damned and that person be freed,<br />

Or shouting zindabad in someone else’s name --<br />

At least that unnecessary ruckus<br />

would not taint the neighbourhood today.<br />

Just a cluster of gentle trees caught in abrupt gusts of wind,<br />

Shook out their hair like some indiscreet woman in a courtyard,<br />

And the emerging, zealous singer from next door<br />

Raised a self-composed tune<br />

On the harmonium and sang of clouds three times.<br />

In came a few men wearing raincoats; they are addicted to tea.<br />

Habitually they spoke to each other:<br />

“What am I going to do?<br />

My teeth are falling out but salary never sees a raise.<br />

I visit the doctors alright, but my body is failing:<br />

Heart disease, eye disease -- everything is going from bad to worse!”<br />

Someone with a poor sense of humour intervened:<br />

“You know what this means, right?<br />

This rain always means hiring vehicles, unnecessary expenses.”<br />

An arthritic patient cleared his throat:<br />

“Hey boy, don’t you forget to add an extra slice of lemon in my tea!”<br />

All these meticulous details and ordeals of their lives<br />

We easily ignored in the rain that day<br />

Because it had rained heavily and gone on forever,<br />

At the request of the ceaseless rain pouring out of the dark skies<br />

We had to lie down side by side all day<br />

We had to read the novel written all over our hearts!<br />

(Translated by <strong>Arts</strong> & <strong>Letters</strong> Desk)<br />

10<br />

11<br />

ARTS & LETTERS DHAKA TRIBUNE | THURSDAY, august 3, <strong>2017</strong><br />

DHAKA TRIBUNE | THURSDAY, august 3, <strong>2017</strong><br />

ARTS & LETTERS

Shamsur Rahman (Oct 13, 1929 – 17 Aug, 2006)<br />

The poetic<br />

sensibility of<br />

Shamsur Rahman<br />

Mask<br />

Shower me with petals,<br />

heap bouquets around me,<br />

I won’t complain. Unable to move,<br />

I won’t ask you to stop<br />

nor, if butterflies or swarms of flies<br />

• Kaiser Haq<br />

Shamsur Rahman is by general agreement our foremost poet. Many consider<br />

him the most significant poet in Bengali since the five great first generation<br />

modernists in Bengali poetry – Jibanananda Das, Amiya Chakrabarty,<br />

Sudhindranath Dutt, Buddhadeb Bose, Bishnu Dey – who turned away from<br />

Tagore’s romanticism and incorporated the lessons of European modernism<br />

in their work. Each of these poets was distinctive in the particular variation<br />

of modernism adopted. Jibanananda’s was a complex post-Romantic<br />

sensibility that conflated reality and the dream world; Amiya Chakrabarty<br />

was a sophisticated cosmopolitan who could write with equal grace about his<br />

own roots and about his self-exile in the West, Sudhindranath was a classicist<br />

and a post-Symbolist who bore an easily recognizable kinship with Mallarme<br />

and Valery; Buddhadeb owed much to Baudelaire but eclectically imbibed<br />

the lessons oflater modernists; Bishnu Dey was the most Eliotesque of the<br />

generation, at least at the outset, and later incorporated a Marxist outlook.<br />

The diversity among these poets was essential to the vitality of their<br />

influence, since it gave their successors a wide range of ex<strong>amp</strong>les on which<br />

to model themselves. Shamsur Rahman was conspicuous in his affinities<br />

with his predecessors, especially Buddhadev Bose and Jibanananda Das,<br />

when he began writing in the late forties, but soon after began blending other<br />

influences, both Bengali and Western. The result, spread over more than<br />

seventy volumes, is a poetic oeuvre remarkable for its versatility and the<br />

st<strong>amp</strong> of the poet’s individual voice.<br />

Broadly speaking, the development of Rahman’s poetry, from a languorous<br />

dreamy verse to a more vigorous exercise in poetic exploration, has a parallel<br />

in Yeats. Though at the beginning Rahman was through and through a<br />

‘private’ poet and his audience was a coterie, his position in the broader<br />

cultural context was significant. He and those of his contemporaries -- Hasan<br />

Hafizur Rahman, Al- Mahmud, Shaheed Quaderi and others -- who were, so to<br />

speak, his allies in pioneering the modem trend in Bangladeshi poetry, were<br />

in effect creating a counterculture vis-a-vis the policies dictated from Karachi,<br />

Pindi and Islamabad. As opposed to poets like Farrukh Ahmed and Golam<br />

Mostafa, who were blinkered in their vision by the ideology of Pakistan,<br />

the self-conscious modernism of these poets was accompanied by a liberal,<br />

secular outlook.<br />

The importance of this became obvious later, because the work of a poet<br />

like Rahman paralleled on the cultural plane, and at one point merged with,<br />

the economic and political struggle that culminated in the liberation war. As<br />

Rahman responded more and more explicitly to the changing socio-political<br />

The importance of this became obvious later,<br />

because the work of a poet like Rahman<br />

paralleled on the cultural plane, and at one point<br />

merged with, the economic and political struggle<br />

that culminated in the liberation war<br />

scene, his poetry became more ‘public’, more direct in its technique, yet<br />

without sacrificing his personal tone. The sheaf of poems he wrote as an exile<br />

at home during the liberation war is a case in point.<br />

Always prolific, Rahman became more so in his later years, and<br />

continued to delight, provoke and move his readers with his observations<br />

and meditations till his last days. One coming to his poetry cannot but be<br />

impressed by their range, both thematic and stylistic. From the short lyric to<br />

the dramatic monologue, from strictly rhymed verses to flexible mixed forms,<br />

he has handled all modes with effortless mastery. He is equally interesting in<br />

his treatment of topical and historical. subjects and tbe timeless themes of<br />

poetry - political turmoil. war, political leaders; the many faces of love, the<br />

exploration of the self, the passage of time; mortality. While remaining firmly<br />

rooted in his Bangladeshi milieu (one might even say his Dhaka milieu, for,<br />

apart from brief visits abroad he has spent his whole life in this old city) his<br />

sensibility is refreshingly cosmopolitan; it can draw upon his native tradition<br />

as well as upon diverse foreign sources - classical Europe, Biblical lore, modern<br />

Western art, etc.•<br />

This City<br />

This city holds out a wizened hand to the tourist,<br />

wears a patched kurta, limps barefoot,<br />

gambles on horses, quaffs palm beer by the pitcher,<br />

squats with splayed legs, jokes, picks lice<br />

from its soul, shakes off bed-bugs.<br />

This city is a cut-purse, scoots at the sight<br />

of a Policeman, looks about with eyes like the naming moon<br />

This city raves deliriously, teases with riddles.<br />

bursts into lusty song, sheds the sweat<br />

of its brow on its feet in tireless factories,<br />

dreams at times of cradles,<br />

ogles the pretty girl standing quietly on the verandah.<br />

In scorching April or monsoon-drenched June<br />

This city put its mad shoulder to the wheels<br />

Of pushcarts, makes for the brothel at nightfall,<br />

Burning with desire to celebrate the flesh,<br />

This city is syphilitic, it tosses and turns<br />

between the white walls of a hospital ward,<br />

This city is a suppliant at the pir’s doorstep,<br />

wears charms and talismans<br />

on its arms, round its neck,<br />

Day and night this city vomits blood,<br />

never tires of funeral processions.<br />

This city tears its hair in a frenzy, dashes its head<br />

on the walls of dark prison cells,<br />

This city rolls in the dust, knowing hunger<br />

as life’s solitary truth,<br />

This city crowds into political rallies,<br />

its heart tattooed with posters<br />

becomes an EI Greco reaching for lofty azure.<br />

This city daily wrestles with the wolf with many faces.<br />

Indifferent to the scent of jasmine and benjamin,<br />

to rose-water and loud lament,<br />

I lie supine with sightless eyes<br />

while the man who will wash me<br />

scratches his <strong>amp</strong>le behind.<br />

The youthfulness of the lissome maiden,<br />

her firm breasts untouched by grief,<br />

no longer inspires me to chant<br />

nonsense rhymes in praise of life.<br />

You can cover me head to foot with flowers,<br />

my finger won’t rise in admonishment.<br />

I will shortly board a truck<br />

for a visit to Banani.<br />

A light breeze will touch my lifeless bones.<br />

I am the broken nest of a weaver-bird,<br />

dreamless and terribly lonely on the long verandah.<br />

If you wish to deck me up like a bridegroom<br />

go ahead, I won’t say no<br />

Do as you please, only don’t<br />

alter my face too much with collyrium<br />

or any enbalming cosmetic. Just see that I am<br />

just as I am; don’t let another face<br />

emerge through the lineaments of mine.<br />

Look! The old mask<br />

under whose pressure<br />

I passed my whole life,<br />

a wearisome handmaiden of anxiety,<br />

has peeled off at last.<br />

For God’s sake don’t<br />

fix on me another oppressive mask. •<br />

Note: Banani - An affluent suburb of Dhaka. It has a well known cemetery.<br />

(Reprinted with permission from Selected Poems: Shamsur Rahman<br />

[Pathak Samabesh, 2016]. The book is available on Rokomari and at the<br />

Pathak Samabesh Kendra, Shahbagh, Dhaka).<br />

settle on my nose, can I brush them away.<br />

12<br />

13<br />

ARTS & LETTERS DHAKA TRIBUNE | THURSDAY, august 3, <strong>2017</strong><br />

DHAKA TRIBUNE | THURSDAY, august 3, <strong>2017</strong><br />

ARTS & LETTERS

Play<br />

Just Pink<br />

• Urmi Masud<br />

Characters:<br />

Themis: Goddess of Justice. She is a middle aged woman,<br />

wearing a long skirt and top with a pussy bow. She is lanky.<br />

Both her hands are half bandaged or she can wear wrist guards.<br />

She has Greek goddess hair either in a twist or a braid. She is<br />

confident, cynical, prejudiced, slightly arrogant, maintains a<br />

straight posture and sits with her legs crossed.<br />

PR: A woman who is older than Themis. She is dressed<br />

professionally according to her designation. She carries a<br />

folder with justice symbol on it. She is a bit fidgety and a bit<br />

cowering in posture next to the goddess. She maintains a lower<br />

tone of voice while addressing the goddess. It is apparent she is<br />