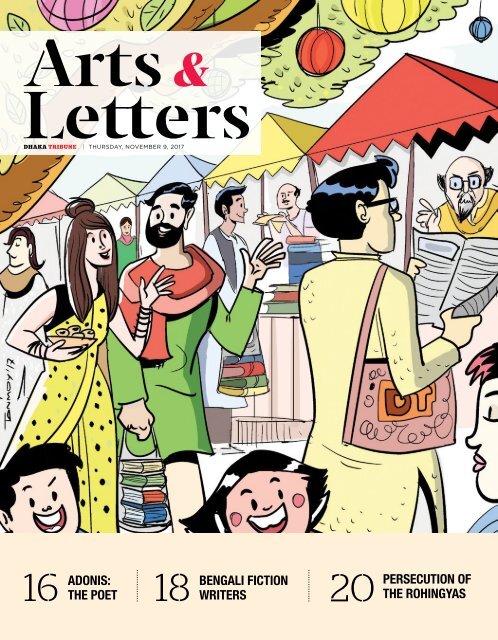

Arts&Letters November2017

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

DHAKA TRIBUNE | THURSDAY, november 9, 2017<br />

16<br />

adonis:<br />

18<br />

the poet<br />

Bengali fiction<br />

writers<br />

20<br />

persecution of<br />

the rohingyas

2<br />

Editor<br />

Zafar Sobhan<br />

Editor<br />

Arts & <strong>Letters</strong><br />

Rifat Munim<br />

Supplement Team<br />

Sayeeda T Ahmad<br />

Mir Arif<br />

Marouf<br />

Luba Khalili<br />

Shuprova Tasneem<br />

Design<br />

Mahbub Alam<br />

Alamgir Hossain<br />

Shahadat Hossain<br />

Cover<br />

Syed Rashad Imam<br />

Tanmoy<br />

Illustration<br />

Syed Rashad Imam<br />

Tanmoy<br />

Colour Specialist<br />

Shekhar Mondal<br />

Two poems by Adonis<br />

Song<br />

– translated by Khaled Mattawa<br />

from ‘Elegy for the First Century’<br />

Bells on our eyelashes<br />

and the death throes of words,<br />

and I among fields of speech,<br />

a knight on a horse made of dirt.<br />

My lungs are my poetry, my eyes a book,<br />

and I, under the skin of words,<br />

on the beaming banks of foam,<br />

a poet who sang and died<br />

leaving this singed elegy<br />

before the faces of poets,<br />

for birds at the edge of sky.<br />

The Beginning of Speech<br />

– translated by Khaled Mattawa<br />

The child I was came to me<br />

once,<br />

a strange face<br />

He said nothing We walked<br />

each of us glancing at the other in silence, our steps<br />

a strange river running in between<br />

We were brought together by good manners<br />

and these sheets now flying in the wind<br />

then we split,<br />

a forest written by earth<br />

watered by the seasons’ change.<br />

Child who once was, come forth—<br />

What brings us together now,<br />

and what do we have to say?<br />

Editor's note<br />

Bringing out this special issue has been a wonderful experience of literary and intellectual<br />

exercise that involved cooperation and contribution, through interviews and articles, from a<br />

wide array of writers from around the world.<br />

This is a 32-page arrangement dedicated solely to the Dhaka Lit Fest 2017. All the articles,<br />

reviews, profiles and interviews in this issue, in some way or another, introduce readers to the<br />

Bangladeshi and foreign writers and artistes who are attending the country’s biggest literary<br />

festival this year. In some cases, Bangladeshi writers (or writers of Bangladeshi origin), some<br />

of whom are speakers themselves, have written in lucid prose about the foreign authors and<br />

speakers joining this year. Foreign authors have also contributed through interviews. This<br />

spontaneous response from the authors, I must say, has been the most exciting part of this<br />

creative exercise.<br />

Putting together the articles, keeping in mind the need for representing all genres and<br />

branches of art, has been a challenging task, which would not have been possible without the<br />

contribution of a brilliant team of young writers, journalists and graphics designers from the<br />

Dhaka Tribune who worked very hard to make this supplement happen. Thanks are also due to<br />

Dhaka Tribune’s Editor Zafar Sobhan and its Publisher Kazi Anis Ahmed, who’s also a director of<br />

the DLF, for their all-out support.<br />

I hope readers find it a read worth their while.<br />

Rifat Munim<br />

War<br />

Kaiser Haq<br />

For Khademul Islam<br />

Sir<br />

Said the interviewer<br />

You have fought<br />

For the country’s independence<br />

Yes<br />

In 1971<br />

I was one of the hundred<br />

Thousand strong<br />

Rag-tag army<br />

Of freedom-fighters<br />

Now<br />

That Victory Day<br />

Is approaching<br />

Once again<br />

Can you tell us<br />

In a few words<br />

What is war<br />

Well<br />

War is war<br />

But what is it like<br />

It’s like sex<br />

There are two<br />

Parties<br />

You sniff around<br />

The other Party<br />

Stalking<br />

Taking a good look<br />

You wait<br />

Humming a silly tune<br />

Excitement rises<br />

At a sighting<br />

You have a brush<br />

You follow<br />

You try to corner<br />

Close in<br />

For a big bang<br />

But war<br />

Is not like sex<br />

In one simple respect<br />

It cannot<br />

Give<br />

Mutual satisfaction<br />

ARTS & LETTERS DHAKA TRIBUNE | THURSDAY, november 9, 2017

From the Directors of Dhaka Lit Fest:<br />

A note<br />

The seventh edition of Dhaka Lit Fest (DLF) will host over 200<br />

speakers, performers and thinkers, representing 24 countries,<br />

making it our largest and the most diverse gathering so far.<br />

Together we can take a moment to enjoy our achievement:<br />

Dhaka and indeed Bangladesh is firmly placed on the international literary<br />

calendar.<br />

Like every year, our programme will celebrate diversity and pluralism,<br />

other languages and cultures, whilst highlighting our own, which is our<br />

way of saying “no to walls,” walls of all kinds. We have more in common<br />

with the rest of the world than we sometimes care to remember. Let<br />

the three days of DLF be a reminder for the importance of unity, bring a<br />

glimmer of hope in an age of pessimism, and inspire minds -- young and<br />

experienced -- to strive for all the things worth fighting for: Freedom of<br />

expression, freedom of thought and the importance of words.<br />

This year we are honoured to be able to host not one but two literary<br />

prizes. We hope you will join us for the announcement of the prestigious<br />

DSC Prize for South Asian Literature as well as the Gemcon Literary<br />

Awards, the highest monetary value literary prize in Bangladesh, at our<br />

festival. Other highlights include panels discussing timely issues, oneon-one<br />

interviews, readings and recitations, film screenings, and book<br />

launches. The festival will feature winners of the Man Booker, Goethe,<br />

Wolfson, Orange, Olivier, the Oscar and numerous other international<br />

awards. In such a rare gathering of luminaries, which is special anywhere<br />

in the world, we take pride in highlighting our own literary and artistic<br />

talents.<br />

We are excited to launch Granta in Bangladesh, a literary journal that<br />

needs no introduction, and we hope this foundation will be the platform<br />

for more Bangladeshi writers -- writing in Bangla and English -- to be<br />

published in their pages and read by millions around the world. It is in<br />

this spirit that we have been working throughout the year to promote<br />

translations of Bangla writing. We wish to thank all our sponsors, patrons,<br />

partners, supporters, our hosts Bangla Academy, and a special mention<br />

goes to the Ministry of Culture.<br />

We have recently opened our borders to over half a million Rohingyas<br />

purely on humanitarian grounds. In doing so, in spite of being a developing<br />

nation, we outclassed many rich nations, and our Prime Minister -- aside<br />

from earning plaudits -- won hearts from all around the world. We hope<br />

an event like DLF will help draw the world’s attention away from tired<br />

stereotypes to the evolving nature of our ever resilient, ever advancing<br />

country. We could go on, but we will conclude our note here by thanking<br />

you -- our audience -- for your energy, enthusiasm, and especially the love,<br />

which you show through your participation every year. We are able to take<br />

the festival to such heights because of you.<br />

– Sadaf Saaz, Ahsan Akbar, K Anis Ahmed<br />

Directors, Dhaka Lit Fest<br />

3<br />

DHAKA TRIBUNE | THURSDAY, november 9, 2017<br />

ARTS & LETTERS

The story of DLF<br />

How things have changed!<br />

Sadaf Saaz,<br />

director and<br />

producer of Dhaka<br />

Lit Fest, is a poet.<br />

Sari Reams, her<br />

first collection<br />

of poems, was<br />

published by<br />

University Press<br />

Limited in 2013.<br />

4<br />

• Sadaf Saaz<br />

When we started the festival we had ambitious dreams. Despite<br />

having a rich tradition of literature stretching back well over<br />

a thousand years, Bangladeshi writing remained largely unknown<br />

throughout the world. Contemporary writers, apart<br />

from a few, were also cut off from the global literary landscape. We wanted the<br />

festival to feature the best of our literature and culture, past and present, and<br />

be a platform take our stories way beyond our borders. We envisaged bringing<br />

the world’s greatest minds to Bangladesh – to inspire a new generation to<br />

think broadly and diversely, beyond the confines of an insular nationalism; to<br />

be inspired to put in the dedication to produce work that could stand among<br />

the best.<br />

While our mission to connect across borders and engage with other literatures<br />

and cultures was the original impetus for the festival, our growth<br />

throughout recent years has been achieved in the backdrop of a new reality,<br />

that none of us imagined when we embarked on this journey. The early years<br />

of the festival were encouraging – it felt like a renaissance of sorts. New English<br />

imprints and literary journals emerged, modern translations were commissioned,<br />

our authors were starting to get international book deals and took<br />

part in international literary festivals, and we had begun connecting to fellow<br />

writers, poets, agents and publishers across the world, alongside celebrating<br />

the pluralism and syncretism of Bangladesh.<br />

The ramifications of the war crime trials, the murder of writers and publishers<br />

in Bangladesh, and further killings and threats against creative personalities,<br />

progressives and foreigners, and importantly, the changing global scenario<br />

with the rise of extremisms and intolerance, has meant that over time<br />

the festival has taken on a new urgency. This space matters. Nearly every year<br />

since 2012 we have been asked if we will cancel the festival. Even though we<br />

have faced numerous challenges, we felt that it was more important than ever<br />

that we continue to encourage discourse and dialogue, to have the difficult<br />

conversations that we need to have, to explore alternate narratives, and to<br />

actually talk to each other rather than being smug in our own echo chambers.<br />

As Bangladeshis we have always been passionate about language, and the<br />

freedom to express ourselves. Yet suddenly that which we had always taken<br />

for granted was under threat. In 2015 we decided to rebrand the festival to<br />

bring Dhaka to the forefront. In that year we were faced with unprecedented<br />

obstacles, with 19 authors dropping out; and yet we were still determined to<br />

keep the festival going, In the end, over 15,000 attended despite a shutdown<br />

of Facebook right before the festival, a strike on the first day of the festival,<br />

and the execution of war criminals on the final evening.<br />

What had started out as a great idea to take Bangladeshi literature to the<br />

world, and to bring a part of the world to us, has turned into somewhat of a<br />

mission to stand up for what we believe in. To continue to protect a space for<br />

free discourse at a time when around the world such spaces are under pressure.<br />

While connecting with the world, we are also rediscovering ourselves<br />

-- and our roots of tolerance and respect for different cultural influences, by<br />

bringing, for ex<strong>amp</strong>le, rural theatrical and oral forms to urban Dhakaites, as<br />

well as the rest of the world. We feature a range of diverse topics, from fiction<br />

to literary non-fiction, poetry to history, science to graphic novels, in what is<br />

truly festival of thoughts and ideas. Every year we have strong women’s panels,<br />

bringing out stories that need to be heard -- from women’s monologues,<br />

to strides made by young women in different professons, to discussing why<br />

what a woman wears needs to be discussed. This year there will be sessions on<br />

sexual violence, and a celebration of stories of super-girls. We are also having<br />

those difficult conversations surrounding religion and sexuality, to counteract<br />

growing fundamentalist forces. In 2012 we came under criticism for holding<br />

an international festival on the grounds of Bangla Academy, the soul of Bangla<br />

literature. However, the festival has emerged as an important forum where<br />

Bangla is side by side with English, with audiences engaging with both English<br />

and Bangla writers, and attending sessions in both languages, rather than<br />

being in separate worlds. We have also have had simultaneous translations in<br />

selected sessions from last year into both languages. Translations have always<br />

been a mainstay of our festival year upon year, as have celebrating almost-forgotten<br />

languages of this region.<br />

As we move into our 7th year, it seems pressing to question the way we<br />

look and talk about literature. We feel Dhaka Lit Fest can be a place to try and<br />

change perspectives from an anglophile, or west vs east divide, to bring out<br />

important but often marginalised voices from the periphery, and to encourage<br />

a range of narratives that may not be represented in popular discourse. It also<br />

seems urgent to have conversations of global relevance, some of which do not<br />

seem as possible in the places that we had previously turned towards, to challenge<br />

and interrogate the status quo. •<br />

ARTS & LETTERS DHAKA TRIBUNE | THURSDAY, november 9, 2017

Interview<br />

‘It is about celebrating diversity and pluralism’<br />

Ahsan Akbar on the elaborate arrangement of DLF 2017<br />

As a festival director, how do you feel about Adonis, the greatest living poet<br />

in Arabic, joining this year’s Dhaka Lit Fest?<br />

Like my two co-directors, I feel extremely happy and proud to be able to<br />

bring a living legend of world literature all the way to Bangladesh. It must be<br />

mentioned, that without the strong recommendation from Sir Vidia and Lady<br />

Naipaul, this wouldn’t have been possible. That is also a great testament to<br />

the brilliance of not just our organising capabilities of the festival, but also to<br />

the warmth, enthusiasm and love the Naipauls felt from our audiences when<br />

they were here last year. Let me take this opportunity to thank everyone,<br />

and a special mention to Khademul Islam, who gave Sir Vidia company one<br />

afternoon when I couldn’t.<br />

Born in 1930, Adonis is 87 now, and has been living in Paris for the most<br />

part of his life. He speaks little English – fluent in French and of course Arabic<br />

– and hardly attends literary festivals, preferring his solitude to write and you<br />

can see the prolific number of books coming out every year.<br />

My co-director K Anis Ahmed and I went to see him in Paris last year. It was<br />

our only way to convince him to come to Dhaka. We were delighted when he<br />

asked us to meet him in Les Deux Magots, which as our readers would know,<br />

is a famous café in Saint-Germain-des-Prés area, known for its rich literary<br />

connections. Adonis charmed us by his calligraphic skills, while signing our<br />

copies of his books, and the numerous stories from his remarkable – yet<br />

struggling – life. Towards the end of the evening Adonis said two things that<br />

I’ll always remember. “You have eyes like a poet”, to me, and to his daughter:<br />

“Dhaka, Dhaka… we have to go, Anis and Ahsan came to see me, so I have<br />

to go see them”. Adonis is a man of his word, and tremendous honour, to be<br />

undertaking this long journey at this age for us.<br />

The international lineup boasts some of the biggest luminaries in different<br />

areas of art. Would you shed some light on the idea of the mix?<br />

We do this every year, and consciously. It is about celebrating diversity and<br />

pluralism. So for ex<strong>amp</strong>le, we have Sir David Hare, one of the worlds leading<br />

playwrights joining us along with his wife Lady Nicole Farhi. Theatre is<br />

important, as is any form of the arts, and fashion design is another strand of<br />

creative expression. But there are other conversations to be had, which may<br />

not seem apparent immediately. For ex<strong>amp</strong>le, is traditional theatre going to<br />

be obsolete in the age of Netflix, or should it adapt more technology to draw<br />

in the crowds? Sir David has a lot to say on this, for ex<strong>amp</strong>le.<br />

After doing it for seven years, we think we know what our audiences enjoy,<br />

and it is the diversity of the panels that make our programme particularly<br />

strong whilst ensuring that literary themes are very much at the forefront of<br />

the festival.<br />

It is evident that the DLF is getting ever stronger in terms of embracing<br />

writers and artistes from diverse cultures and fields. Is this aspect going to<br />

constitute one of the main themes of the festival this year too?<br />

Yes, indeed. This year we have over 200 speakers, performers and artists<br />

representing 24 countries, and that’s a considerable jump from last year when<br />

we had 18 countries represented. Whilst we dream of more inclusivity, one<br />

must also keep in mind the increasing costs of putting on the festival every<br />

year. We are grateful to two big supporters of our event: the Ministry of<br />

Culture and Bangla Academy, and our private sponsors are really wonderful<br />

for they “get it.”<br />

Many corporate houses in our country, and the profitable ones with huge<br />

amounts of revenues coming their way, sadly don’t even see the merit of a<br />

literary festival. We know because we approach them for sponsorships<br />

every year, scoring luck with the few names of corporate houses and<br />

institutions you see on our posters. If one doesn’t invest in promoting the<br />

arts, it’s not just myopia but also, in some way, irresponsible. If we want to<br />

fight extremism in our country, we certainly need more patrons of the arts<br />

and culture. Not wanting to sound to pessimistic, if we struggle to raise<br />

money every year, we have two options: 1) to reduce the diversity of the<br />

festival, i.e. make it a smaller programme and 2) end the idea completely.<br />

We certainly don’t want to do either of them, and we definitely are not<br />

going to start charging tickets, unlike many festivals around the world.<br />

Tell us something about the local Bengali authors, writers and activists whose<br />

works and voices will be highlighted this year.<br />

We take a lot of pride in showcasing our talents to the rest of the world.<br />

Can you imagine a festival that invites all kinds of luminaries, only to have<br />

nothing to show from their own turf? I mean that would be so unfortunate<br />

and unworkable too. Fortunately we are blessed with some amazing literary<br />

minds and artistic talents in our country. We have two books from the Library<br />

of Bangladesh series. I’m particularly looking forward to the launch of two<br />

novellas by Imdadul Haq Milon, translated by Saugata Ghosh. But most of all,<br />

I’m thrilled to hear Helal Hafiz read from his works; one of my favourite poets,<br />

and I believe it would be special for anyone who is familiar with contemporary<br />

Bangla poetry.<br />

We have tremendously eloquent speakers who can discuss and debate on<br />

a number of contemporary issues: Masuda Bhatti, Mahbub Aziz, Salimullah<br />

Khan, Nasreen Jahan, Hossain Zillur Rahman, Firoz Ahmed and Aly Zaker who<br />

is a man of many talents. We have wonderful fiction writers like Moinul Ahsan<br />

Saber, Selina Hossain, Zakir Talukder, and many others joining us. Celebrated<br />

poets like Nirmalendu Goon, Asad Chowdhury and the younger generation of<br />

poets like Shamim Reza and others. See page 6<br />

5<br />

DHAKA TRIBUNE | THURSDAY, november 9, 2017<br />

ARTS & LETTERS

David Hare<br />

Hit your time and speak to your time<br />

His politics is what makes him one of the most anticipated speakers at DLF 2017<br />

Abdus Selim<br />

is a writer and<br />

translator. He is<br />

professor of English<br />

and Linguistics<br />

at North South<br />

University and<br />

Cental Women’s<br />

University. He’s<br />

the sole Bengali<br />

translator of one<br />

of Hare’s plays.<br />

• Abdus Selim<br />

Though being a stage play devotee I had<br />

come across David Hare’s name as a highly<br />

acclaimed British playwright of our<br />

time long before, it was not until I listened<br />

to a Hard Talk interview of him on BBC in<br />

2010, perhaps conducted by Tim Sebastian,<br />

that I was incentivised to explore online<br />

for more information on his literary<br />

works. In Bangladesh, as we all know, it is<br />

not easy to find the latest foreign publications<br />

as one desires or requires.<br />

As implied, watching the Hard Talk interview<br />

was a thoroughly refreshing experience<br />

for me especially because of his<br />

candid assertions and liberal standpoints<br />

on contemporary political events—about<br />

Iraq war in particular. My online surfing<br />

strongly endorsed the impression that<br />

I’d already acquired listening to his interview,<br />

and a ready ex<strong>amp</strong>le can be found in his comments that he made to<br />

The Sunday Telegraph once, “I wanted a social democratic government, and I<br />

thought Blair was the best prime minister for 50 years.”<br />

After a few years, in 2008, The Telegraph again in an article titled ‘Sir David<br />

Hare: This knight is haunted by a sense of betrayal,’ the writer of the article<br />

William Langley phrased the playwright’s disillusionment like this, “He [David<br />

Hare] spent years raging against the dying of the Left, then thought he’d<br />

found a savior in Tony Blair. His new play shows what happens when the messiah<br />

turns out to be a Judas.”<br />

I could also get hold of two very significant quotes (undated) of David Hare<br />

on politics, politicians and creative writers at the time of my web surfing and<br />

find them very relevant contextually. The first reads, “What politicians want<br />

and what creative writers want will always be profoundly different, because<br />

I’m afraid all politicians, of whatever hue, want propaganda, and writers want<br />

the truth, and they’re not compatible.” This reminds me of my reading and<br />

translation of Shakespeare’s King Lear in which the duke of Gloucester, after<br />

his eyes were gouged out, was advised by Lear to get two glass-eyes fixed like<br />

the politicians (they have natural glass-eyes that never show the reality) because<br />

those glass-eyes would make him see things like politicians who could<br />

easily see what the common people never could (all-out development of the<br />

country). And the second, which happens to be the prompt of my title for the<br />

present article, “The most important playwright’s gift is to hit your time and<br />

speak to your time.”<br />

In fact, David Hare is a truth-finder and in no way a propagandist, and at<br />

the same time a creative writer who hits his time and speaks to his time as<br />

well. This I came to know when I read his two plays in 2011, Stuff Happens<br />

(2004) and The Vertical Hour (2006), both of which were themed on the Iraq<br />

War—the first on pre-war political hullabaloo and viciousness of the two big<br />

powers, USA and UK, and the second on its aftermath.<br />

Immediately after the Hard Talk experience, I happened to be on a trip<br />

to the USA and wasted no time in buying three plays by David Hare out of<br />

which my perfect and of course very thoughtful selection was The Vertical<br />

Hour. The reason was, the playwright uniquely presented his honest ideas<br />

and arguments on the aftermaths of the Iraq War and also what the British<br />

people thought about it. Upon reading the play, I was soon tempted to render<br />

it into Bangla, especially to show our readers and drama lovers how politically<br />

significant a British playwright could be regarding a very heated and divided<br />

issue of our time. Though I am biased towards verbatim translation of plays<br />

and opposed to their adaptations, for a particular reason, I, for the first time,<br />

opted for transformation of the play into a Bangladeshi framework. The reason<br />

was, as far as the Iraq War was concerned, opinions of both the British and<br />

the Bangladeshi people were, and still are the same. It was a war fought for<br />

nothing causing death to thousands of people and giving birth to many more<br />

unforeseen political and humanitarian crises! My task of adaptation thus became<br />

easy.<br />

But that is not the lone reason for my being fascinated with the plot of the<br />

play. Other reasons are the underlying interplay of some never-ending issues<br />

like Freud, Oedipus, atheism, dialectical and historical materialism of Karl<br />

Marx, real life anecdotes, free and frank discourses on age-long clash between<br />

capitalism and communism, ethnic cleansing in East Europe and Arab countries,<br />

local/home made and global terrorism, hypocritical modernism, journalistic<br />

ethics and most of all, human fragility and frailty vis-a-vis enigma of<br />

love. All of these materials have taken the play to a mystic and meaningful<br />

height. Though my adapted play titled Prolombito Prohor in Bangla could not<br />

have more than three stage performances so far, I still feel it has an inherent<br />

potential of contemporaneity that will help shape human feelings and logic<br />

rationally.<br />

Though David Hare has confessed, “I fell into writing plays by accident. But<br />

the reason I write plays is that it’s the only thing I’m any good at,” he is so good<br />

at it that he rightly hits his time and speaks to his time by being both socially<br />

and politically true and conscious. •<br />

6<br />

Continued from page 5<br />

What are the most anticipated events and panels of DLF 2017?<br />

I’d say if one looks at the programme in full, s/he will be torn between<br />

panels -- every panel we have put together is actually brilliant and a lot of<br />

thought and hard work went into them. We have over 100 sessions and each<br />

has been carefully selected and curated. Some of the bigger names -- who<br />

are well known to our audiences -- will draw more crowds and there won’t<br />

be enough seating space during their sessions: Adonis, Ben Okri, William<br />

Dalrymple, Lionel Shriver, Helal Hafiz, Nirmalendu Goon, and of course,<br />

our beloved White Witch from Narnia: Tilda Swinton! My tip: come early,<br />

come for the whole day and chalk out a plan amongst your friends to secure<br />

seats in the sessions and there will also be the surprises. For ex<strong>amp</strong>le,<br />

Granta launch will be special as will be the literary prize giving ceremonies.<br />

Is there any feature that you think distinguishes this year’s arrangement<br />

from the previous ones?<br />

We will have three things that will stand out: 1) more security because we<br />

have already doubled the number of online registrations from last year,<br />

2) two literary prizes including the announcement of the prestigious DSC<br />

Prize for South Asian Literature, which was hosted by Jaipur Literature<br />

Festival and a A-list name from Hollywood. That doesn’t happen every<br />

year, as its not done easily, and you certainly don’t want to miss it, nor you<br />

want to sit at home when some of the biggest names are in your city. It’s too<br />

good to be true: a free ticket to see all these names in one venue over one<br />

weekend. If someone told me this when I was growing up in Dhaka in the<br />

1980s/90s, I would have thought two words: “wishful thinking.” •<br />

www.ahsanakbar.com<br />

@kobial<br />

ARTS & LETTERS DHAKA TRIBUNE | THURSDAY, november 9, 2017

Profile<br />

Tilda Swinton:<br />

Master of metamorphosis<br />

• Hamilton Hodell Agency<br />

Born into a family from the Scottish Borders, Tilda Swinton worked<br />

as a humanitarian volunteer in Africa for two years after she left<br />

school, following which she studied social and political sciences at<br />

Cambridge University.<br />

She started making films with the English experimental director Derek<br />

Jarman in 1985, with Caravaggio. They made seven more films together,<br />

including The last of England, The Garden, WarRequiem, Edward II (for<br />

which she won the Best Actress award at the 1991 Venice International Film<br />

Festival), and Wittgenstein, before Mr Jarman’s death in 1994. She gained wide<br />

international recognition in 1992 with her portrayal of Orlando, a film based<br />

on the novel by Virginia Woolf and directed by Sally Potter.<br />

Swinton has also appeared in Spike Jonze’s Adaptation; David Mackenzie’s<br />

Young Adam; Mike Mills’ Thumbsucker and Francis Lawrence’s Constantine;<br />

Béla Tarr’s The Man from London, Andrew Adamson’s blockbuster The<br />

Chronicles of Narnia tales; Tony Gilroy’s Michael Clayton – for her performance<br />

in which, she received both the BAFTA and Academy Awards for Best<br />

Supporting Actress of 2008 – and Erick Zonca’s Julia, which won for Swinton<br />

the Evening Standard’s Best Actress award and which performance was<br />

named as Indiewire’s hands-down favourite of that year.<br />

In 2010, Swinton shot Lynne Ramsay’s We Need to Talk about Kevin which<br />

went into the main competition at Cannes the following year to huge critical<br />

acclaim. She also starred as Minister Mason in Snowpiercer, directed by Bong<br />

Joon Ho and released in 2014 for which she won numerous critics’ awards<br />

for best supporting actress at the end of that year. Tilda also features in the<br />

critically acclaimed comedy Trainwreck, from Amy Schumer, directed by Judd<br />

Apatow, the Marvel Studios blockbuster Doctor Strange, from director Scott<br />

Derrickson, War Machine, directed by David Michod and most recently the<br />

critically acclaimed Netflix and Plan B feature, Okja directed by Bong Joon Ho.<br />

She has established rewarding ongoing filmmaking relationships with Jim<br />

Jarmusch (Only Lovers Left Alive, Broken Flowers and The Limits of Control),<br />

with Lynn Hershman-Leeson with whom she made Conceiving Ada, Teknolust<br />

and Strange Culture, with fine artist Doug Aitken, for Sleepwalkers and Song 1 –<br />

which took over the entire facades of MoMA and the Smithsonian respectively<br />

– with Wes Anderson on the movies Moonrise Kingdom in 2011 and The Grand<br />

Budapest Hotel in 2014, with the Coen Brothers on Burn after Reading and<br />

Hail Caesar! and especially with Luca Guadagnino alongside whom she has<br />

worked for over 20 years, made several experimental projects – the widely<br />

applauded I Am Love which she co-produced over the span of a decade, 2016’s<br />

celebrated A Bigger Splash and the forthcoming Suspiria – and with whom she<br />

is producing a number of projects for the future.<br />

In 2016, The Seasons in Quincy: Four Portraits of John Berger was premiered<br />

at the Berlinale, an essay film about the writer and philosopher, which she cowrote,<br />

co-produced and co-directed with The Derek Jarman Lab.<br />

In 1995 she conceived and performed her acclaimed site-specific live-art<br />

piece The Maybe – in which she presents herself lying asleep in a glass case –<br />

which was originally performed at The Serpentine Gallery in London with an<br />

installation she devised in collaboration with sculptor Cornelia Parker. The<br />

following year, in collaboration with the French artists Pierre et Gilles, she<br />

performed the piece at the Museo Baracco in Rome.<br />

In 2013, she revived The Maybe at MoMA in New York, where the specifics<br />

of its incarnation there meant that it appeared unannounced, unaccompanied<br />

by an artist’s commentary, official images or finite schedule, in various spaces<br />

in the museum.<br />

In the summer of 2008 Swinton, in collaboration with Mark Cousins,<br />

In 2016, The Seasons in Quincy: Four Portraits<br />

of John Berger was premiered at the Berlinale,<br />

an essay film about the writer and philosopher,<br />

which she co-wrote, co-produced and codirected<br />

with The Derek Jarman Lab<br />

created the Ballerina Ballroom Cinema of Dreams – a grassroots, joyfully<br />

anarchic, family-based film festival in her hometown of Nairn, Scotland,<br />

intended as a one-off, not to be repeated, event. In 2009 Swinton and Cousins<br />

both co-curated a Scottish Cinema of Dreams edition in Beijing and also<br />

brought another festival to Scotland – A Pilgrimage. This week-long event<br />

involved a mobile cinema that travelled and was bodily pulled for an hour<br />

each day, from Kinlochleven on the west coast of Scotland to Nairn on the<br />

east coast. All three festivals – unique and un-repeated – became events of<br />

considerable international interest. She has curated and produced a number<br />

of other film-related events from Iceland to Thailand.<br />

Tilda and Olivier Saillard have created four original performances together<br />

– The Impossible Wardrobe in 2012, Eternity Dress in 2013, Cloakroom in 2014<br />

and Sur Exposition in 2016 – all performed for the Festival d’Automne in<br />

Paris. In 2015, Swinton and Saillard co-authored a box of books, published by<br />

Rizzoli, documenting the first three of these works.<br />

This autumn, Tilda was the guest speaker at the British Film Institute’s<br />

Luminous Gala, which sees the industry’s most celebrated figures come<br />

together to raise important funds for the BFI. In October, she was an honoree<br />

at the prestigious Lumiere film festival in Lyon.<br />

She is the mother of twins and lives in the Scottish Highlands. •<br />

7<br />

DHAKA TRIBUNE | THURSDAY, november 9, 2017<br />

ARTS & LETTERS

Essay<br />

Ben Okri:<br />

Redefining the worlds<br />

of fiction and reality<br />

Syed Manzoorul<br />

Islam is one of<br />

Bangladesh’s most<br />

famous fiction<br />

writers. He’s also<br />

a speaker at DLF<br />

2017.<br />

8<br />

• Syed Manzoorul Islam<br />

When Ben Okri was awarded the Booker Prize for his novel The<br />

Famished Road in 1991, the news was flashed in the front page<br />

of many Dhaka dailies. A reporter of a Bangla daily, out of his<br />

admiration for him, added a few lines of his own to a Reuters<br />

report where he said that the prize was a vindication of Okri’s power to evoke<br />

the magical and the spiritual as a defence against the all-pervasive material<br />

culture of our time. I read the news with obvious satisfaction as I had begun<br />

to appreciate his storytelling skills after reading Incidents at the Shrine which<br />

had come out a few years earlier. I found the reporter’s enthusiastic comment<br />

not quite off the mark, as Okri had indeed made the magical and the mystical<br />

an integral part of the everydayness of the people and community he wrote<br />

about. I planned to buy a copy of the book and read it at my leisure, but the<br />

literary editor of a daily where I wrote a regular column commissioned me to<br />

write a review of the book and gave me only a week.<br />

He sent me a copy of The Famished Road which sat on<br />

my table for a couple of days as I struggled to finish<br />

the tasks at hand. I almost wished Okri hadn’t got the<br />

prize that year as reading a book under compulsion<br />

was no fun. But when I finally picked up the book I<br />

found it a compelling read just as Incidents was, except<br />

that it was a novel and Okri had more space to spin<br />

his narrative webs. I still remember how I was drawn<br />

by the stories of the earlier book into a strange world<br />

which was as starkly real as a warfield and as mystical<br />

as dimly remembered dreamscapes. The eight stories<br />

of the book deal with such subjects as the Biafran war,<br />

the endemic poverty that Okri saw in marginalised<br />

communities in his country, and the military rule in<br />

many of the African nations that has left a myth of<br />

”the street of hate” as a legacy to be painfully borne<br />

by Okri’s generation. I was fascinated by the way he<br />

used a variety of narrative perspectives—sometimes<br />

looking at the world through the eyes of a ten-yearold<br />

boy, sometimes from the point of view of a man<br />

relentlessly haunted by images, and sometimes<br />

through the lens of a strangely detached observer<br />

who communicates through signs and symbols that<br />

relate to a deeper level of meaning. Okri appears<br />

to believe that there are stories everywhere, which, like Bruce Chatwin’s<br />

“Songlines,” assume a voice if someone with an appreciation of the unseen<br />

and the unknown cares to listen.<br />

Reading The Famished Road, I was once again intrigued by Okri’s use of<br />

the narrator figure who, in this novel, is a spirit child named Azaro (meaning<br />

“born to die” in Yoruba) who combines in his tiny but stubborn frame the<br />

quintessential storyteller and a suffering soul who endures poverty and<br />

violenece but is determined to help his family and the community. He<br />

alternately inhabits the world of reality and the world of dreams where space<br />

and time lose their meaning, so his narrative contains both the imprints of<br />

reality and the dream logic of a beguiling narrative, except that for most part<br />

of the novel it’s hard to tell which one is which. This confusion is an aspect<br />

of Azaro’s growth and prepares him to face the inevitable: Either he fights to<br />

keep his place in the world of the living or is whisked off to the world of the<br />

unborn by his spirit friends. The two worlds that Azaro lives in often overlap,<br />

and each, in strange ways, defines the other. While the spirit world and the<br />

world of hunger and suffering clash around him, Azaro has to remain steadfast<br />

in the pursuit of his mission.<br />

The Famished Road employs a language that is rich and evocative, and at<br />

times, poetic. I later read some of Okri’s poems whose narrative frames seem<br />

to belong to the extraordinary world of his fiction which exits at many levels.<br />

Like Azaro, Okri also straddles the world of realistic storytelling and the world<br />

of mythical dreamscapes.<br />

His evocation of the magical has led some critics<br />

to consider him a magical realist in the same vein as<br />

Gabriel García Márquez. But I tend to believe that his<br />

magical world is not an alternative, or even a parallel<br />

to lived reality but an inherent part of it so that the<br />

spiritual, the fantastic and the unknown become<br />

integral to its complex fabric. Reality for him does not<br />

exist in one dimension; it rather has several overlapping<br />

dimensions and layers. When reality becomes thus<br />

layered, it ceases to offer clear outlines, and every layer<br />

assumes a validity of its own. This happens in folklore<br />

narratives and this also happens in life when the world<br />

closes in and we begin to look for a way out.<br />

Okri has been a crusader against rights abuse and<br />

discrimination on the grounds of class, colour, race and<br />

ethnicity. At the same time he cautions fellow writers<br />

against playing for the western gallery by writing<br />

about “overwhelming subjects” such as colonialism,<br />

slavery and war. He too writes about these subjects<br />

but without being told by others, and in a way that<br />

upholds the uniqueness of his storytelling heritage.<br />

Like a public intellectual, he rallies people around<br />

issues that touch people’s lives today. I’ve noticed with<br />

interest how Jeremy Corbin draws from the strength of<br />

Okri’s idealism and conviction; how Obama became a<br />

figure for him who could change the world and effectively equalise the demons<br />

that Trump has released. The survivors of London’s Grenfell tower fire drew<br />

immense solace from the poem he wrote on the tragedy which pricked the<br />

conscience of people across England. What I particularly admire is Okri’s use of<br />

irony in the poem that clinches his argument well before it is fully articulated.<br />

In the poem he evokes TS Eliot in these lines:<br />

Those who were living are now dead<br />

Those who were breathing are from the living earth fled<br />

The oblique reference to Eliot’s lamentation for a world gone waste and his<br />

pinning hopes on a spiritual regenaration seems particularly striking as, for<br />

Okri, regeneration of the human spirit is not a hope but a necessity. His social<br />

activism and his fictional endeavour are both directed at laying the ground for<br />

regeneration to happen across cultures. •<br />

ARTS & LETTERS DHAKA TRIBUNE | THURSDAY, november 9, 2017

Book review<br />

Zeppelins and hyacinths: Esther Freud’s<br />

novel ‘Mr Mac and Me’<br />

• Neeman Sobhan<br />

Even as I write this review, I’m tempted to re-read Esther Freud’s<br />

shimmering, compelling eighth novel that refuses to be pigeonholed.<br />

War looms on its horizon, like “the belly of a Zeppelin ... a second<br />

moon,” yet it is not just a novel about war. Nature abounds,<br />

sensuously observed through the pristine eyes of the child narrator, who sees<br />

the sun as “just a slither of a yolk above the trees,” and intuits, observing an<br />

artist, that wild flowers can grow on the ground and on a painter’s canvas. Yet,<br />

this is neither just a coming-of-age story nor merely a fiction based on facts<br />

about a year in the life of a famous artist. It is all of this and more.<br />

As the gripping story unfolds, summer is not yet over on the Suffolk<br />

coastline, but the seaside village of Walberswick is shaken up by the outbreak<br />

of the First World War. Visitors evacuate in droves; regiments of soldiers<br />

arrive to be billeted locally till they cross into Belgium; local youths enlist,<br />

leaving the village to the women, the elderly and the children. Faced with the<br />

stringent security regulations of the Defence of the Realm Act, the locals grow<br />

paranoid over the possibility of any spies amongst them.<br />

The only “foreigner”<br />

remaining in the village, a<br />

loner with binoculars, comes<br />

under suspicion. This is “Mr<br />

Mac.” Unbeknownst to the<br />

locals, he’s the renowned<br />

and controversial Scottish<br />

architect and artist Charles<br />

Rennie Mackintosh, who<br />

designed the Glasgow School<br />

of Art, but feeling underappreciated<br />

he moved here<br />

with his artist wife.<br />

Only a sensitive young boy,<br />

Thomas Maggs, the crippled<br />

12-year-old son of the abusive<br />

village pub-keeper, longing<br />

for adventure follows the<br />

artist and trusts him, the two<br />

forming a mentor-protégé<br />

relationship of sorts.<br />

This is the beating heart of<br />

a lyrical story, told in the first<br />

person by Thomas, blending<br />

fact and fiction. To me, the factual, the oblique biography of Mackintosh in<br />

his declining years painting his famous botanical watercolours, interested me<br />

less than the fictional exploration of a war-torn English village in the 1900s.<br />

Esther Freud, the great-grand daughter of Sigmund Freud and daughter of<br />

Lucien Freud the painter, has with psychological insight and an artist’s eye for<br />

detail painted a novel of beauty and compassion.<br />

What fascinated me more than the world of artists and art, was the life of<br />

the artisans: The stories of the farmers, the fishermen, the rope-makers, the<br />

pig-raisers, the hired herring-gutting highland girls, all following their age-old<br />

trades, battling the crushing poverty, and the extra hardships brought on both<br />

by the war and the onslaught of industrialisation, with machinery replacing<br />

human labour.<br />

But no matter how dire the life led by young Thomas is, his experience<br />

of the external world of nature and events, and the internal one of complex<br />

relationships and emotions are described within short chapters in the most<br />

resonant prose.<br />

The impact is poetic but the language fits a boy’s perceptions and<br />

vocabulary, encompassing his sense of wonder and quiet wisdom:<br />

“I can hear the woodpigeons burbling, the sound as round as pebbles.”<br />

In a hencoop: “I duck into the dark stink of the shed … close my palm over<br />

the smooth, hot, newborn shells.” Extinguishing flames: “The fire hisses like<br />

a nest of snakes.” About his violent father, “ … wishing I hadn’t seen that look<br />

on Father’s face which means it’s a drinking day and there’s nothing I can do.”<br />

If I must cast a critical eye, there is just one area in which the book<br />

stumbles a bit. This is when some of the biographical material or history of the<br />

village is crowded into dialogues or monologues. A glaring ex<strong>amp</strong>le is when<br />

Mackintosh, normally laconic when explaining his art to the watchful Thomas,<br />

suddenly inundates him with his back-story and professional frustrations. In<br />

awkward chunks of dialogue, one hears the author’s voice dictating from a<br />

written script.<br />

Here is Mac recounting a conversation he had with his boss Keppie:<br />

“‘I’ve made places for poets,’ I told him, ‘and now I’m being reprimanded<br />

for misplacing toilet facilities.’ But Keppie came closer. He was pale. Business<br />

was failing off, he told me, the city was struggling, and his job was to please<br />

the client. ‘While mine,’ I shouted, I could feel the whole office listening at<br />

the door, ‘is to make them gasp and wonder.’ That was when he asked me to<br />

go … ’”<br />

This jarring literary device is used again with the rope-maker, George<br />

Allard, endlessly lecturing his apprentice Thomason about the history of<br />

Britain. With his captive audience rotating the wheel, Allard walks backwards<br />

into the woods releasing the strands of hemp wound around his waist, while<br />

reeling out facts and dates, obviously meant for the readers.<br />

Yet this art of making rope, when described by the narrator, sounds like<br />

visual melody. There is an especially sublime moment when Thomas is<br />

walking backwards into the countryside releasing the taut yarn, and he is<br />

greeted by a girl he knows. He wants to but cannot interrupt his work, and<br />

the realisation of his true feelings for her comes as he keeps walking away:<br />

“They have forgotten me already, I think, as they dip out of sight over the rise<br />

of the small hill, but just then Betty leans over and flicks at the rope and I feel<br />

ittravel, the touch of her finger, right down until it twangs against my gut.”<br />

This is writing that brings fiction alive. Thus, Thomas is more real to me<br />

than the real-life artist Mackintosh. Weaving and braiding strands of facts<br />

and fiction, and flicking the rope with her creative magic, Esther Freud sets<br />

vibrating in our guts an imagined world. I carry away a line uttered as dialogue<br />

by “Mr Mac,” but which was in a lecture Mackintosh delivered in Glasgow:<br />

“Art is the flower. Life is the green leaf.” •<br />

Neeman Sobhan<br />

is a poet, fiction<br />

writer and<br />

columnist. Her<br />

poetry collection,<br />

Calligraphy of<br />

Wet Leaves, was<br />

published by<br />

Bengal Lights<br />

Books in 2015.<br />

9<br />

DHAKA TRIBUNE | THURSDAY, november 9, 2017<br />

ARTS & LETTERS

Bengali fiction<br />

Selina Hossain:<br />

Seeker of the new<br />

Pias Mazid is a<br />

young poet, fiction<br />

writer and essayist<br />

who writes in<br />

Bengali.<br />

Marzia Rahman is<br />

a fiction writer and<br />

translator.<br />

10<br />

• Pias Mazid<br />

(Translated by Marzia Rahman)<br />

A<br />

true artist is one who would go against all odds to appease his/<br />

her creative soul. S/he keeps searching for new clusters of cloud<br />

and fresh rays of sunlight. In her literary voyage spanning more<br />

than four decades, Selina Hossain has been deftly doing just that,<br />

dedicating her life to the world of fiction. A versatile wordsmith working across<br />

genres -- short fiction, novels, children literature, prose writings and essays --<br />

with the aim of sketching the lives of men and women who come mostly from<br />

the underprivileged groups. She has an oeuvre that encompasses everything<br />

-- sorrows and suffering of flood-affected people, the rebellious youth of the<br />

Language Movement, the freedom fighters during the Liberation War, people<br />

living in enclaves, people fighting with incurable diseases or people shattered<br />

by the devastating after-effects of the Sepoy Mutiny.<br />

Hossain’s journey started with short fiction. Her first book, a collection of<br />

short stories, Utsho theke Nirontor, came out in 1969. She was only 22 back<br />

then and yet had the courage to portray the true face of a conservative society.<br />

The book was much appreciated by renowned author-critic Humayun Azad<br />

who welcomed the fresh new voice of defiance to the world of literature.<br />

Utso Theke Nirontor was just the beginning and Hossain never looked back;<br />

she kept seeking out the real picture of society with numerous other works<br />

of short fiction such as Jolobotee Megher Batash (1975), Khol Korotal (1982),<br />

Porojonmo (1986), Manushti (1993), Onura Purnima (2008), Narir Rupkotha<br />

(2009), Obelar Dinkhon (2009), Mrityur Nilpadma (2015) and Nunpanter<br />

Goragori (2015). The diversity of her subject matter, cultural context and<br />

literary techniques varies from one novel or story to another. We are amazed<br />

to see that the writer who so candidly writes stories like Shukher Pithe Shukh<br />

could aptly deliver books on the revolutionary Che Guevara or poet Pablo<br />

Neruda as well. Not merely depicting a story, her work does more than that,<br />

creating a subtle connection between the readers and the stories that she<br />

creates. Even the simplest narrative becomes a fine specimen of art with her<br />

magical touch. And we proudly and gladly acknowledge that with writers like<br />

Hossain our short fiction is not a dying art; rather it has a promising and a<br />

fulfilling, bright future.<br />

Primarily a novelist, Hossain has already published over 30 novels. She has<br />

given this genre a new life, a new dimension. With diverse topics, varied style<br />

and the use of simple language, her novels have established her as one of the<br />

finest fiction writers in Bengali. On one hand she narrates the tale of Kalketu<br />

and Phullara while bringing forth the story of Pritilata, the fiery woman who<br />

was martyred during an armed battle against the British colonisers. Her novels<br />

encompass both past and present, interweaving them into fine stories. Often<br />

she makes use of materials from real life events and situations -- such as<br />

the horrific killing of Shomen Chandra at the hands of fascists, the killing of<br />

Munier Choudhury by the collaborators or the loss of her daughter Lara. Some<br />

of her well-known novels are Josnay Surjyo Jala (1973), Jalochchwas (1972),<br />

Hangor Nodi Grenade (1976), Magna Caitanye Shis (1979), Japita Jiban (1981),<br />

Podoshobdo (1982), Neel Moyurer Joubon (1983), Chand Bene (1984), Poka<br />

Makorer Ghor Bosoti (1986), Nirantar Ghantadhwani (1987), Ksharan (1988),<br />

Katatare Prajapati (1989), Khun O Bhalobasa (1990), Kalketu and Fullora<br />

(1992), Bhalobasa Pritilata (1992), Tanaparen (1994), Gaayatree Sondhya<br />

(1996), Dipanwita (1997), Juddho (1998) and Lara (2000).<br />

One of her finest works is Jomuna Nodir Mushyara (2011). In this novel,<br />

though the main subject is poet Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib Hossain<br />

acquaints readers with the mystery of many continents. The personal loss<br />

of poet Ghalib in the story represents loss and pain felt by generations of<br />

poets, writers and artists. One of her latest works, Gachhtir Chaya Nai (2012),<br />

captures the sad story of an incurable disease that brings people of different<br />

continents under the same circumstances.<br />

Hossain also writes essays. She has given nonfictional work focused<br />

on history a new dimension, not restricting it to dates and times, rather<br />

presenting the story with her unique style of writing. Nirbhoy Koro Hai, Mukto<br />

Koro Bhoi and Nijere Koro Joi are among her acclaimed nonfiction works.<br />

Her work touches both the native soil and the foreign land, trying to judge<br />

art by examining her own experiences. In her essays she has delved into the<br />

creative world of such eminent personalities as Abbas Uddin, Mohammad<br />

Mansuruddin, Syed Walliullah, Gabriel García Márquez and Mario Vargas<br />

Llosa. Her comment on the Japanese author Osamu Dazai in her essay “Dajai<br />

Osamur Shilpo Bhubon” can easily be extended to powerful writers of all<br />

countries and all times.<br />

For Hossain, writing fiction for young readers is not simply an entertainment.<br />

Rather, she deems it a noble way to illuminate young readers with the world of<br />

Bengali literature. Her book Golpe Bornomala (1998) presents Bengali language<br />

and its vocabulary to the young minds in an interesting way. Her young adult<br />

fictions include Onnorokom Jawa, Akashpori, Jokhon Brishti Name, Golpota<br />

Shesh hoi na, Mihiruner Bondhura, Nil Tunir Bondhura, Kurkurir Mukhtijudho,<br />

Phulkoli Prodhanmontri Hobe and Noditir Ghum Bhengeche. In these novels,<br />

she has successfully introduced youngsters to the 1971 Liberation War and the<br />

plights of underprivileged children.<br />

In Noditir Ghum Bhengechhe she has engaged children in the magical story<br />

of a dead river turning alive. The story has a deep symbolic connotation: The<br />

young generation would bring forth new life from the very ruins of destruction.<br />

This is why Hossain narrates the stories of resurrection to the young readers.<br />

First and foremost a feminist, Selina Hossain has also placed underprivileged<br />

people and ethnic minorities at the centre of her works. She nurtures an allencompassing<br />

vision. Always the one to tell her stories in a subtle narrative,<br />

she never forgets to bring in the sweet chatters of a bird nesting in the branches<br />

of our life, and that’s exactly how her voice is young forever. •<br />

ARTS & LETTERS DHAKA TRIBUNE | THURSDAY, november 9, 2017

‘Bangladeshi literature is really outstanding’<br />

Interview<br />

• Mohammad Marouf<br />

Annisul Hoque, one of Bangladesh’s celebrated fiction writers, speaks to<br />

Dhaka Tribune about Bengali literature and the Dhaka Lit Fest 2017<br />

You have been with the Dhaka Lit Fest since its inception. As it brings its<br />

seventh edition to town, what is your personal feeling?<br />

Every festival is a joyous occasion. People want to know about our country<br />

when I travel abroad. For limited scope, some people don’t know much about<br />

us. Bringing together poets, writers and artistes from different countries, the<br />

Dhaka Lit Fest provides an opportunity for them to learn about our country and<br />

literature. Similarly, we also have the opportunity to learn about the literature<br />

of many other nations. This is really a heartening aspect of the festival.<br />

We know that poets, writers and literary figures play an important role in<br />

resolving social or historical crises. Being a hub of literary doyens, do you<br />

think the DLF can play a role in addressing the growing number of crises and<br />

instability around the world?<br />

You have brought up an important issue. Historically and nationally, we<br />

have always relied on cultural movements. Our poets, writers and the overall<br />

cultural sector played a huge part in the Language Movement in 1952 and the<br />

Liberation War in 1971. We know that in our neighbouring country Myanmar a<br />

brutal massacre has been carried out on an ethnic minority group, for which we<br />

are providing shelter to around 600,000 Rohingya refugees in a small country<br />

like ours. Our government is working on the repatriation process and forming<br />

global opinion that will put pressure on Myanmar to stop the persecution of the<br />

Rohingyas. The Dhaka Lit Fest can also play a big role in resolving the Rohingya<br />

crisis by mobilising global opinion. The organisers of the lit fest as well as our<br />

poets and writers should discuss this issue with foreign guests and inform them<br />

of the scale of its atrocity and the role of our country.<br />

The DLF provides strong platforms for translation of<br />

Bengali literature into many different languages. How<br />

do you evaluate this? Do you think such an event may<br />

widen the horizon of Bengali literature on the world<br />

stage?<br />

Bangladeshi literature is really outstanding. Even if our<br />

literature doesn’t get translated, there is no reason to<br />

think that it has fallen behind. However, it is true that<br />

except Rabindranath, works of other writers have not<br />

been adequately translated. But I also believe that when<br />

fiction writers come up with quality works of fiction,<br />

nothing can stop them from getting international recognition. However, it<br />

will be wrong to think that publishing works in English naturally comes with<br />

increased quality and wide circulation; we should not decide to write in English<br />

based on such hollow assumptions. There is no doubt that when a reputed<br />

publishing house publishes our work in translation, it comes as a significant<br />

step. But for that to happen we have to write in Bengali. If the quality of writing<br />

is outstanding, it will definitely find skilled translators and make a distinct place<br />

in world literature on its own merit.<br />

Are there any aspects relating to the DLF that you’d like to comment on?<br />

I would like to talk about one aspect. We need to be watchful while taking<br />

care of our foreign guests -- from hotels to chauffeuring the guests to the<br />

programme and back to their rooms. At the same time, we also need to<br />

be watchful that the respect with which we treat our foreign guests is also<br />

shown in treating our local Bengali writers, poets and artistes. All writers<br />

present at the festival, whether foreign or local should be treated in the same<br />

manner.<br />

I do hope that the horizon of DLF as a literary hub continues to broaden in<br />

future. •<br />

‘Maybe it’s time we took a closer look at partition’<br />

• Mohammad Marouf<br />

Shaheen Akhtar is a Bengali fiction writer based in Dhaka. Her magnum<br />

opus, Talash, is a groundbreaking work on the Liberation War in which the<br />

story is told from the points of view of women who were tortured and raped<br />

in captivity by the occupation army. Her other fictional works include Sakhi<br />

Rangamala and Mayur Singhashan. In this interview, she shares her thoughts<br />

about her upcoming novel and the DLF 2017.<br />

You are joining the Dhaka Lit Fest this year. Tell us something about the<br />

panel you are in?<br />

I am participating in the DLF for the fifth time this year. Earlier I read from<br />

my own works, or took part in panel discussions. But this time the discussion<br />

will be about ties between the two parts of Bengal. I guess it will look into<br />

the relationship between Bangladesh and West Bengal of India. It may focus<br />

on aspects of cultural exchange between the two parts of Bengal or aspects<br />

of identity following the partition of Bengal in 1947. I think this will be a<br />

challenging topic to discuss in a short span of time. The reason I’ll be speaking<br />

about this is because I’ve been working on these aspects over the last couple<br />

of years for a novel I’m writing.<br />

Would you share with readers what your new novel is about?<br />

My upcoming novel, which will come out in the Ekushey Boi Mela 2018, is set<br />

in the 1940s of the last century. That was the decade not only of a world war or<br />

the collapse of the British Empire, but also of communal riots with the whole<br />

of India and Bengal being divided based on religious identity. The decade<br />

was marked by unprecedented bloodshed and displacement. Hundreds of<br />

thousands of people had to migrate to a new country, leaving their ancestral<br />

homes overnight. Maybe it’s time we took a closer look<br />

at partition so that we can have a fuller understanding<br />

of its repercussions on our lives.<br />

Tell us something about your experience of the<br />

ambience at the DLF on the Bangla Academy grounds?<br />

With literary discussions, bookstalls, snacks corners<br />

and ceaseless adda, the DLF creates an international<br />

atmosphere at the Bangla Academy premises. Listening<br />

to foreign writers is always inspiring for me. Literary<br />

journals publish their interviews and discussions, and<br />

this makes the whole thing very exciting. However,<br />

unlike a film festival, it’s not easy to talk about your<br />

works in a literature festival. With the help of subtitles,<br />

two filmmakers from two different countries can learn about each other’s<br />

works, but people who write in their native languages feel at a loss sometimes<br />

as, for them, it all depends on whether their works have been translated or not.<br />

So, you think translation of Bengali fiction and poetry is immensely<br />

important?<br />

Yes, precisely. The prerequisite for literary exchange and expansion of our<br />

literature is translation of Bengali works of fiction and poetry into other<br />

languages. And those translations have to be published as well. University<br />

Press Limited has been doing it for a long time. The books wing of The Daily<br />

Star has also taken some good initiatives. The Dhaka Translation Center and<br />

Bengal Lights Books are now playing a key role in translating Bengali literature.<br />

If this trend continues, I am very optimistic that Bengali literature will find its<br />

deserved place in the international arena. •<br />

11<br />

DHAKA TRIBUNE | THURSDAY, november 9, 2017<br />

ARTS & LETTERS

History<br />

William Dalrymple, the wayfarer<br />

• Shazia Omar<br />

Shazia Omar is<br />

a Bangladeshi<br />

fiction writer. Her<br />

second novel,<br />

Dark Diamond,<br />

was published by<br />

Bloomsbury India<br />

in 2016.<br />

12<br />

When asked which of William Dalrymple’s books has most<br />

influenced me, I have to pause to weigh them up. My<br />

introduction to the author of 11 best-sellers was not In Xanadu<br />

(written when William was 21) or City of Djinns, though many<br />

people say these travelogues inspired a wanderlust that came to define their<br />

lives.<br />

I first read White Mughals, the tragic love story of East India Company<br />

officer James Kirkpatrick, a British Resident at the court of the Nizam of<br />

Hyderabad in 1798, and Kahir un-Nissa -- the great-niece of the Nizam’s prime<br />

minister. With humour and empathy, William gives us the details to bring to<br />

life magnificent Mughal India.<br />

Next I devoured The Last Mughal which chronicles the siege of Delhi after<br />

which the British took the city and exiled Bahadur Shah Zafar II, the last<br />

Mughal emperor. I had the opportunity to watch William and Vidya Shah<br />

present this history at the Dhaka Hay Lit Fest 2014 in a seamless blend of<br />

literature, poetry and music. Despite his busy schedule, William made time<br />

to support Bangladeshi writers at our lit fest and is coming again this year to<br />

do the same.<br />

I visited India once many years ago, my first trip with my father and sister<br />

after my mother died. We sat where Shah Jahan spent the last of his lonely<br />

days imprisoned, watching the glorious Taj in a diamond mirror; we prayed<br />

amidst the mystic fervour of Ajmer Sharif as we tried to piece ourselves back<br />

together. Reading William’s book took me back to those tender days.<br />

I enjoyed William’s documentary Sufi Soul:<br />

Mystic Music of Islam and loved the Qawali band he<br />

introduced at the Jaipur Lit Fest 2010. Incidentally,<br />

the JLF, William’s gift to writers, is the largest<br />

collection of lit lovers in the world, presenting an<br />

opportunity for writers and aspiring writers to join<br />

a growing community of support.<br />

These books, documentaries and experiences<br />

were very much a part of the adventure that resulted<br />

in my novel, Dark Diamond, my foray into the blood<br />

and gore that surrounds valuable diamonds in India.<br />

Shortly after, William’s book Kohinoor: The Story<br />

of the World’s Most Infamous Diamond came out. I<br />

saw William and Anita Anand present this book at<br />

JLF 2017 and what amazing storytellers they were,<br />

as captivating as ever, with sagas of loot, murder,<br />

torture, violence, deceit and colonial greed!<br />

I also saw William present his latest history book,<br />

Return of a King: The Battle for Afghanistan, which<br />

tells the story of Britain’s invasion of Afghanistan. I<br />

was drawn in not only by William’s research skills --<br />

he did “the Indiana Jones-kind of research, dodging<br />

bullets and getting rare manuscripts” -- but also by<br />

his enthusiasm which makes his writing and storytelling<br />

larger than life.<br />

“Journalism has the pleasure of instant<br />

gratification,” says William. “It is like a very nice Bengali sweet -- some mishti<br />

doi or some gulab jamun or something that you pop down and feel a delicious<br />

sugar rush hit you. It is instantaneous. A history book is more like a huge<br />

Mughlai feast with an enormous raan and Peshawari naans that will sustain<br />

you, and is a substantial thing, it takes a long time to prepare. History books<br />

are real hard work. They are exhausting to do and are no more fun than going<br />

to the dentist. But at the end of it, you do something you are proud of, and<br />

which will stay on the shelves, hopefully, forever.”<br />

This brings me to Nine Lives: In Search of the Sacred in Modern India, a series<br />

of biographies that explore the rich religious heritage of the subcontinent.<br />

Of the biographies, one might think my favourite would be that of Lal Peri<br />

Mastani, the ecstatic red fairy who lives and dances at the shrine of Lal<br />

Shahbaz Qalander. I was happy to see William discuss the rising threat of<br />

Wahabism. “Arabisation of Islam” is all too pervasive in Bangladesh too and<br />

it would be good for us to have a few more writers<br />

speaking about it.<br />

My favourite story though, the one that had the<br />

greatest impact on me, was about Prasannamati<br />

Mataji. Drawn to the ascetic purity of Jainism, she<br />

plucks out each strand of hair, wears unstitched<br />

cotton saris and lives off charity alone but it is not<br />

until she watches her best friend and fellow nun<br />

starve herself to death that her faith is truly tested.<br />

She then decides to follow this route and starves<br />

herself too. What struck me was the fortitude with<br />

which she faces death.<br />

On July 2, 2016, Holey Bakery was attacked by<br />

terrorists. Holey had been a shrine for us. We went<br />

there for Thursday night dinner, Friday afternoon<br />

tea, Saturday morning brunch. It was our oasis in<br />

the urban jungle of Dhaka. When terrorists swarmed<br />

the place, we watched on television with tears in our<br />

eyes and prayers on our lips, feeling helpless. When<br />

we heard the next morning of the massacre, I felt<br />

all courage drain out of me. As it was, I was wearing<br />

around me a blanket of fear following the brutal<br />

killings of 23 people. For one month, I stayed home,<br />

a zombie. My friends encouraged me to be bold, to<br />

write and teach yoga and take my children out of<br />

the house, to defy the terrorists. I could not. I kept<br />

thinking of my young nephew who died on that bloody day, of the mere boys<br />

who perpetrated the crime, brainwashed into thinking that they were doing<br />

something noble. I began spiralling into depression.<br />

That was when I read Nine Lives. The story of the nun, who with courage<br />

and determination faced death, played like a mantra in my head and finally<br />

helped me find the strength to face the day. I am ever grateful to William<br />

for finding this nun and sharing her tale with all the pathos and pain which<br />

perhaps only he could do. His words have not only expanded my horizon but<br />

also inspired me and helped me in countless ways. •<br />

ARTS & LETTERS DHAKA TRIBUNE | THURSDAY, november 9, 2017

History<br />

Why the British empire was the<br />

darkest time in our history<br />

• Shuprova Tasneem<br />

For those of us who are familiar with the history of the British empire as well<br />

as post-Partition events, Shashi Tharoor’s book An Era of Darkness: The British<br />

Empire in India may seem like a rather basic read. Tharoor himself acknowledges<br />

the impossibility of condensing a book on colonial history within 300 pages,<br />

writing that the purpose of the book is not to provide a chronological history of<br />

events in the region, but rather to refute the claim that the British empire was,<br />

at the end of the day, a good thing.<br />

An important rebuttal to colonial nostalgia<br />

Whether it is the rise of British politicians who yearn for the good old days of<br />

Britain when it was truly great - Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson’s inappropriate<br />

recitation of Kipling (“the temple bells they say, Come you back, you English<br />

soldier”) during a recent visit to Myanmar comes to mind - or the yearning for<br />

a romanticised version of the Raj and the Victorian era in popular TV dramas<br />

like Indian Summers and Downton Abbey, the sad truth is that there has been a<br />

resurgence in colonial nostalgia in recent years.<br />

Which is why Tharoor’s book is not only welcome, but necessary in today’s<br />

world. Starting with a comprehensive overview of the looting of India and<br />

the destruction of its industries, the writer reminds us over and over again<br />

that British rule began with the pillaging of a land and its people by a giant<br />

corporation, and ended with a system of government that treated an entire<br />

continent as sub-humans and used a “divide and rule” policy to cling on to<br />

power for as long as possible.<br />

While there are certain bits of the book that seem to jump from one point<br />

to another too quickly, Shashi Tharoor’s arguments are foolproof. He uses<br />

extensive research and resources to demonstrate that whether it is the Indian<br />

Civil Service and legal system, or railways, tea and cricket, every aspect of<br />

British colonial rule that we now use as ex<strong>amp</strong>les of a benign Empire were<br />

not only instruments to cement British<br />

rule, but were more often than not a<br />

lot more detrimental for locals than<br />

we now believe. His discussion on the<br />

Indian railway, and how much British<br />

shareholders actually profited from its<br />

creation, is particularly illuminating.<br />

Should the past stay in the past?<br />

The chapter on famines, forced labour and massacres perpetrated by the British<br />

will have you seething in anger but as many critics point out, all that happened<br />

a long time ago. Surely, the British are no longer culpable?<br />

Tharoor only handpicks a few ex<strong>amp</strong>les from many to show how colonial<br />

rule continues to impact the modern world. One doesn’t have to look too far<br />

- the Penal Code of Bangladesh and its criminalisation of homosexuality and<br />

legalisation of marital rape, among other things, shows how Victorian values<br />

continue to influence us here, today.<br />

And as Tharoor points out, one of the worst parts of Empire was the total lack<br />