Self-Reflection Brochure

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Self</strong>-<strong>Reflection</strong> \<br />

The Portrait<br />

& Its Uses<br />

Wisbech and Fenland Museum

The portrait<br />

has a long cultural history,<br />

emerging in the earliest forms of art such as statuary, coins, religious<br />

and funerary decoration, as well as painting.<br />

As a figurative form of representation, the portrait painting has<br />

an unbroken line of development from the Renaissance onwards.<br />

Based on the skill to render the physical appearance of objects in an<br />

illusionistic manner, figurative art could also be accused of doing no<br />

more than just copying that appearance, something which Academies<br />

placed in the lower ranks of art. They valued the artistic imagination<br />

that could bring subjects from history to life. The portraits<br />

painted by Rembrandt and other Dutch artists of the 17th century,<br />

proved that the form could achieve the highest artist goals through<br />

employing both painterly skills and imagination to convey character<br />

and inner depth.<br />

The first real challenge to portraiture was the emergence of<br />

photography in the mid-19th century. Notwithstanding its size and<br />

monochrome limitation, photography could claim that because it<br />

recorded with light, it was a more accurate representation of the<br />

physical appearance of a person than any painting. However, its<br />

commercial success merely made this cheaper form of a ‘portrait’<br />

more widely accessible to a larger number of people who wanted<br />

to be portrayed.

The advent of Modern Art from the beginning of the 20th century<br />

and its dominance in Western Art until the late 1960s, along with<br />

the development of mass media, was a further attack upon the value<br />

of figurative portraiture. To some extent late 20th century art continued<br />

to relegate this form as an insignificant artistic practice, and<br />

this is still, to some extent, the case with contemporary art, yet the<br />

form itself has never quite ceased to exist.<br />

David Hockney and Lucien Freud along with Damien Hirst, and many<br />

other contemporary artists, have all produced portraits. Hockney’s<br />

recent exhibition at the RA (July-October 2016), containing no less<br />

than 82 portraits, is proof of the ongoing validity of this form.<br />

The photographic portrait, whether of a movie star, or a celebrity,<br />

has dominated our cultural horizon since the mid-20th century.<br />

When we add to this our present fascination with the internet,<br />

social media and digital technology, it is clear that whenever we take<br />

a photo of our friends or a selfie on our mobile phone and post it on<br />

Facebook, we are affirming the enduring fascination for the portrait.<br />

1

Hudson<br />

Room<br />

2

The illusion of portraiture<br />

All two-dimensional surfaces, whether it is a painting, a photograph,<br />

a film or TV screen or indeed the mobile phone screen, are limited<br />

by the fact that they are a flat surface. Consequently, in trying to<br />

represent the real world as we experience it in three dimensions, an<br />

illusion has to be created. The video or photographic image which<br />

appears to represent faithfully the object and its place in space, is<br />

as much a visual illusion as a painting which has to generate illusion<br />

through painterly techniques. The art of the portrait because of<br />

its earliest association with replicating the physical appearance of a<br />

person, had to call upon techniques such as perspective and the use<br />

of light and shade as well as colour and scale to mimic the illusion of<br />

depth, hence suspending our disbelief in relation to the two-dimensional<br />

surface that we are looking at, in order to persuade us that<br />

we are looking at a three-dimensional object.<br />

Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s work is perhaps an extreme example of this<br />

process of the objects created through the marks made, as well as<br />

the colours used, represent the actual plants and fruits, which then<br />

in turn coalesce to suggest the appearance of a face. The illusion can<br />

be broken down quite easily by focusing on the particular plants and<br />

fruits, and then acknowledging that they too are in fact an illusion<br />

since they are no more than marks made by the brush on a twodimensional<br />

surface.<br />

Why are portraits made?<br />

Apart from the obvious answer that portraits are made because<br />

someone commissions them, there are five ways of considering<br />

their function: capture likeness, create a record, display status, and<br />

symbolise concepts. Perhaps the most obvious reason why a portrait<br />

in any medium is made, is to capture the likeness of a particular<br />

individual. Typically, this is as much concerned with the physiognomy<br />

of the face as with the costume and stature of the individual.<br />

3

Elizabeth Josephine Peckover, 1893, Photograph.<br />

4

Portraits can also act to create a record for legal purposes and<br />

identity such as the Wisbech prison photographs in the exhibition,<br />

which serve to record the appearance of the prisoners for future<br />

reference (a process which is still used by the police).<br />

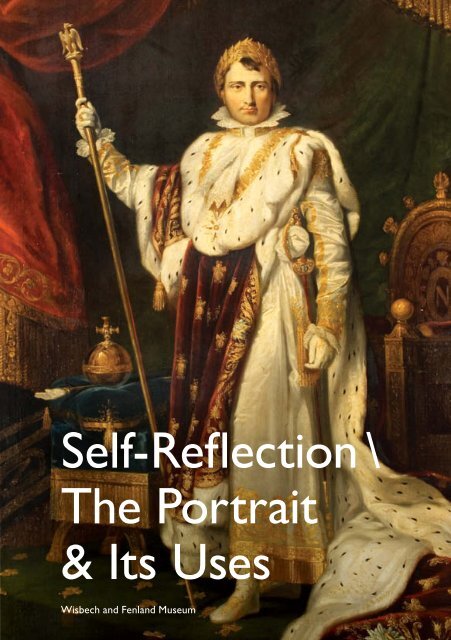

Portraits are also capable of communicating the individual’s status in<br />

society or indeed the wider world. In this form, they are much more<br />

reliant on the external trappings of the office that the person holds<br />

or represents and the symbols associated with that office, as seen<br />

in the portrait of Napoleon I in his Coronation robes or the photograph<br />

of King Radama II of Madagascar, shown in the exhibition.<br />

We generally assume that the portrayed image is a faithful rendition<br />

of the person’s appearance, yet a glance at the coins in our pocket<br />

will tell us that very often such portraits are symbolic representations,<br />

which are much more concerned with conveying a concept,<br />

such as the state or the monarch.<br />

Portraits can do all these things, and in addition, attempt to convey<br />

the character of the person through their appearance, the objects<br />

around them, the context in which they are portrayed, and the<br />

activities with which they may be engaged. The portrait of Chauncy<br />

Hare Townshend is an excellent example of a work which conveys<br />

a sense of the character of this individual through his pose, the<br />

clothes he wears, his hairstyle, and above all by the faithful dog<br />

whose head he is stroking. It would be natural to assume that this<br />

is his pet dog and that he loved this dog so much that he insisted on<br />

it being portrayed alongside himself, and this may indeed have been<br />

the case. However, the history of the use of the dog as a symbol<br />

of fidelity and trustworthiness goes back to funerary monuments,<br />

brasses, and tombs of the Middle Ages where it appears at the<br />

foot of a Knight’s effigy. The artist or perhaps Townshend himself<br />

requested this symbolic reference in the portrayal because of what<br />

he wanted to say about himself.<br />

5

Types of portraits<br />

In producing a portrait, the human fi gure can be represented in a<br />

number of ways and these can be classifi ed as a series of portrait<br />

categories or conventions, which have been in place, more or less<br />

from the emergence of portraiture as a subject in Western art in<br />

the 15th century. Whilst some conventions go further back to antiquity<br />

especially Romano Greek art, such as the profi le portrait, the<br />

bust, the equestrian portrait and the standing portrait – generally<br />

seen in large-scale public sculpture – others have emerged more<br />

recently, and in response to the changing technologies of the time,<br />

such as photography.<br />

The nine categories identifi ed here broadly cover the range of possible<br />

variants in the composition of a portrait, and relate to a range of<br />

functions associated with the portrait. The profi le portrait is clearly<br />

best suited to coins, medals and plaques, whereas the companion<br />

portrait is best suited to the representation of husband and wife.<br />

Typically, the standing portrait is used when it is important to draw<br />

attention to the stature or status of the person or the costume<br />

worn by that person – as is seen in the portrait of Alderman Richard<br />

Young, which hangs in the Wisbech Town Council meeting room.<br />

How valuable are portraits?<br />

The value of the work of art is always a problematic issue because<br />

it is almost entirely dependent upon the status given to the artist,<br />

subject, materials, or skill displayed, and how it is regarded at any<br />

particular moment in history. The emergence of an art market from<br />

the 16th century onwards – the sale and purchase of works of art –<br />

added a new dimension when prominent individuals began to amass<br />

collections, the dimension of monetary worth.<br />

When Vladimir Tretchikoff painted the Chinese Girl, in Cape Town<br />

in 1952/3, using as the model a young woman he had come across<br />

working in a launderette, his own status as an artist was negligible.<br />

6

Balding A: Sister of the Hospital of the Holy<br />

Trinity, Castle Rising, Oil on Canvas.<br />

Napoleon I, Relief.<br />

Skippers: Siamese Twins Chang and Eng<br />

Bunker, 1846, Oil on Canvas.<br />

7<br />

Sanders G S: William Watson, Oil on Canvas.

The resulting work displayed very few aesthetic or artistic qualities<br />

that could have been agreed upon by either collectors or connoisseurs<br />

at that time. It only came to prominence when, in the late 50s<br />

and the early 60s, it was made into a print, and therefore became<br />

widely available at a modest cost, that it achieved its status as the<br />

‘Mona Lisa of Kitsch’, becoming the bestselling art reproduction of<br />

the 20th century. When it sold for $1.5 million in 2013 at the auction<br />

house Bonhams, it achieved a status that was never imagined by<br />

the artist and certainly never envisaged by the model.<br />

When Leonardo da Vinci accepted the commission to paint a portrait<br />

of the wife of the merchant Francesco del Giocondo, sometime<br />

between 1503 and 1506 (this is disputed and there is evidence that<br />

he was still working on it as late as 1517), he certainly did not<br />

imagine that it would become the quintessential representation of<br />

Western art: the Mona Lisa. Nor could he have imagined that this<br />

small panel of poplar wood measuring only 77 cm x 53 cm, painted<br />

with oil colours, currently in the collection of the Louvre in Paris,<br />

would become the most valued, if not priceless, work of art.<br />

Ultimately the question to be answered here is: what is it about the<br />

‘Mona Lisa of Kitsch’ and the ‘Mona Lisa’ which determines their<br />

respective values?<br />

Who owns the portrait?<br />

The photograph of Florence Owens Thomson and her children was<br />

taken by Dorothea Lange in February or March 1936 in Nipomo,<br />

California, during a month-long trip photographing migrating farmworkers<br />

in the state on behalf of the Resettlement Administration.<br />

Later, Lange stated in an interview “there she sat in the lean-to tent<br />

with her children huddled around her, and seemed to know that<br />

my pictures might help, and so she helped me. There was a sort of<br />

equality about it.” (From: Popular Photography, February 1960).<br />

In fact, Lange took a series of photographs of Mrs Thompson and<br />

her children, and it’s clear from the resulting photographs as well as<br />

8

the nature of the photographic equipment being used, that to some<br />

extent, this particular image was very carefully composed. Even<br />

Lange’s later statement suggests that there was an element of cooperation<br />

between the photographer and the model, therefore the<br />

composition and the pose, especially of the children, have been carefully<br />

arranged to convey a particular message. As a migrant worker,<br />

living in a tent with her family, it is clear that Mrs Thompson was<br />

poor, however Lange’s artistic skill turned this image of desperation<br />

into an elegiac representation of motherhood akin to the Western<br />

tradition of the Madonna and child. This of course did nothing to<br />

relieve Mrs Thompson poverty, but through Lange’s artistry keeps<br />

her image before us as an icon of 1930s America.<br />

In total contrast, the ‘selfie’ apparently taken by an Indonesian black<br />

macaque monkey whose curiosity brought it close enough to the<br />

camera, which had been carefully set up by the photographer David<br />

Slater, to trip the shutter resulted in a series of photographs that<br />

have become the basis of an international legal dispute concerning<br />

the copyright of the image. Naturally, the photographer claimed the<br />

copyright, but PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals)<br />

and animal activists brought a legal case to court to assert that<br />

the copyright belongs to the monkey because he/she activated the<br />

shutter. The case is still unresolved, but serves to draw attention<br />

to the issue of ownership of the image. Whilst we might consider<br />

this to be a distracting argument, it is clear that if we choose to<br />

believe that the animal had no active part in the taking of the picture,<br />

then it’s also clear that the photographer did no more than to set<br />

up a camera. Furthermore, the image could not have been taken<br />

without the camera or the particular characteristics of that camera<br />

which ultimately are the result of the designer of the camera and<br />

the company which manufactured it. In other words, the image was<br />

only made possible by the existence of the camera. Consequently,<br />

the camera manufacturer could claim some ownership of the image.<br />

This argument descends into absurdity, but points to a real concern<br />

in the digital multimedia world where, once an image has been<br />

posted on the Internet, the individual who posted it loses all control<br />

or rights over it.<br />

9

How are portraits used?<br />

Religion and the state<br />

The portrait has been used to represent religious values across<br />

world religions (apart from those that ban all realist representations)<br />

as a way of establishing the relationship between the member<br />

of that religion and its key figures.<br />

The emphasis has been on the personification of the values and<br />

ideas through the representation of the religious images. Western<br />

religions tend to emphasise the physical experience of the deity,<br />

such as personal suffering and sacrifice, whereas Eastern religions<br />

such as Buddhism concentrate on the transcendent values of the<br />

experience of the deity.<br />

The state has done the same thing with symbolic representations<br />

of Kings and Queens, Emperors, and Generals, whether that is on<br />

a coin, a medal or a state seal. The actual appearance of the individual<br />

is only the starting point for the personification of the values<br />

represented by that state. It is not accidental, for example, that the<br />

profile representation of the monarch on coins and medals recalls<br />

the earliest uses of this in ancient Rome, and in doing so appeals to<br />

the concept of imperial power represented through the figurehead.<br />

Remembering the dead<br />

From ancient antiquity to the modern day, the most prolific use of<br />

the portrait has been to commemorate the dead. Often part of<br />

complex funerary decoration, the portrait whether in the form of<br />

a painted mask, a death mask, or a mummy case, the intention has<br />

always been to record the status or appearance of the deceased, to<br />

accompany them in the afterlife or more simply as a memento mori.<br />

10

11<br />

Van Sil T: Descent from the Cross, Copy after Rubens, Detail, 1835, Oil on Canvas.

12

Charles the Martyr<br />

Within hours of Charles I’s execution on 30th January 1649, Eikon<br />

Basilike was published. Claimed to have been written by Charles<br />

himself, it is a justification of his actions, and is the basis of the<br />

cult of Charles the Martyr. After the Restoration, he was made a<br />

saint with his Feast-day fixed as 30th January and remained in the<br />

Church’s Calendar until 1859.<br />

The fragment of a portrait of Charles shown on the left was found<br />

in the roof timbers of Walsoken church and presumably served as<br />

an icon of the royal saint, probably as an image to be worshipped<br />

rather than a portrait.<br />

Funerary monuments<br />

The memorial on the north wall of the chancel of St Peter and Paul’s<br />

Wisbech represents Thomas Parke who was born 1543 and died 1st<br />

January 1630 aged 87, and Audrey Parke his wife who died in 1639.<br />

This kind of memorial was popular in the 17th century. It shows<br />

figures representing Thomas and Audrey kneeling at a prayer desk,<br />

and their daughter Elizabeth is shown kneeling in the recess under<br />

the desk. Thomas is in armour of the early 17th century, whereas<br />

Audrey wears a dark cloak or dress with a wide brimmed black hat.<br />

There is a plaque in the centre section which reads ‘to the memory<br />

of their dear and deceased Father Thomas Parke their mother (yet living).<br />

Sir Miles Sandys KNT and Dame Eliz his wife daughter and heir of the<br />

said Thomas Parke erected this memorial’. A skeleton resting above<br />

the figures is a reminder of the vanity of life.<br />

The image of power<br />

Leadership and military prowess has often been displayed through<br />

the ‘uniform of office’ or the physical attributes of the individual -<br />

these are sometimes exaggerated or made the central feature. The<br />

emphasis given to the Imperial coronation robes of Napoleon I, and<br />

13

the trappings of power, as well as the symbols of authority such as<br />

the Imperial Roman Eagle on top of his staff, the Christian orb resting<br />

on the stool, or point to his aggrandising status.<br />

The Rev William Ellis’s photograph of King Radama II, whilst nonetheless<br />

regal, as he is dressed in a suitable uniform of state, with<br />

his crown on the table beside him, makes an interesting contrast<br />

with the image of imperial power represented by Napoleon. There<br />

is some irony here as it was the French who gifted the crown to<br />

Radama II in an effort to persuade him to favour their desire to<br />

bring Madagascar into the French sphere of influence. The British<br />

were in competition for this influence but the French won.<br />

General Giuseppe Garibaldi (4th July 1807 – 2nd June 1882) the<br />

‘hero of two worlds’ whose thrilling deeds during the campaign for<br />

the unification of Italy had unfolded day-by-day through the 1860s<br />

on the front pages of most newspapers, received a tumultuous welcome<br />

wherever he went on his three-week tour of England in the<br />

spring of 1864. His fame as a republican hero was so great that it<br />

generated a personality cult which was quickly exploited by manufacturers<br />

such as Peak Freans, who invented the Garibaldi biscuit in<br />

1861; by printmakers who produced numerous images of Garibaldi’s<br />

exploits, and the Staffordshire potteries who produced statuettes<br />

and busts of the general. In all these portrayals, the key symbolism<br />

is his red shirt, the poncho, his sword and his horse.<br />

The bronze sculpture represents an Oba, a king of Benin (a former<br />

kingdom in modern day Nigeria in West Africa), shown with the<br />

traditional symbols of the palette he holds in his right hand, the<br />

headdress studded with cowrie shells, the shield and necklace, all<br />

testify to his special status. Figures such as these were produced<br />

for the Palace of the Oba in Benin City by metal casting craftsman<br />

from the 12th century onwards, but first came to the attention<br />

of Europeans after the British Punitive Expedition of 1897, which<br />

resulted in the destruction of the kingdom of Benin and the ransacking<br />

of the city and the Palace. This particular example is a work<br />

produced after the restoration of the kingdom by the British in 1914<br />

when the practice of metal casting for the court was revived.<br />

14

In this display only the young Queen Victoria is portrayed through<br />

her feminine attributes, whilst her status is signified by the costume<br />

and hat (reminiscent of portraits of Queen Elizabeth I).<br />

Social class and portraiture<br />

From the privileged…<br />

From the emergence of portraiture in Western art in the Renaissance,<br />

the commissioning of a portrait has always been a sign of privilege<br />

and wealth. Whilst this was initially limited to princes, rulers and<br />

the elite, and controlled by sumptuary laws which limited who could<br />

be portrayed and how they could display their status and wealth, it<br />

gradually extended to bankers and merchants, and ultimately to all<br />

the elite. These early portraits tended to be displayed in the context<br />

of funerary chapels or funerary monuments in churches, palaces and<br />

offices of state. However, as the practice of commissioning portraits<br />

extended across wider social groups such as merchants, they were<br />

typically displayed in the home of the individual.<br />

The companion portraits of Mr Charles and Mrs Louisa Whiting are<br />

a very good example of the desire to demonstrate status as well as<br />

privilege through the commissioning of portraits which would then<br />

be displayed in their home for everyone to see.<br />

Their appearance, the clothes they wear, and the pose all contribute<br />

to their display of status as well as the simple fact that they can<br />

afford to have portraits painted. Displaying a portrait of yourself or<br />

your family in your own home was a clear sign of privilege as well as<br />

wealth, and perhaps a none too subtle reminder of their status in<br />

Wisbech society. Mr Whiting is represented as a gentleman wearing<br />

formal clothes with a high black necktie, holding a newspaper, whilst<br />

Louisa Whiting is shown wearing a fine décolleté dress decorated<br />

with roses and holding a red rose as a sign of her femininity and<br />

beauty.<br />

15

16

17<br />

Mr and Mrs Whiting, Detail, Oil on Canvas.

This statement being made, apart from possessing the money to<br />

commission the portraits, was all about affirming their rank in society,<br />

to suggest something of their character, and to record their<br />

physical appearance for posterity.<br />

We can probably assume that they did look like this but it is highly<br />

likely that the artist would have been instructed to present them<br />

literally in the best light. Consequently, the pose and the clothes,<br />

as well as the attributes they are shown holding, are all part of the<br />

process of generating the desired image of worthy citizens.<br />

…to the eminent…<br />

Those individuals who had achieved status in their own societies<br />

through their actions, character, or contribution to learning or<br />

commerce, were commemorated through portraits commissioned<br />

on their own behalf or by their social peers. The fact that men are<br />

the predominant subject of such portraits is a clear indication of<br />

the relative social status of the sexes and the lack of opportunities<br />

available to women to achieve within their own societies, unless by<br />

accident of birth they were part of a noble or Royal family, and could<br />

come to prominence.<br />

The career of the Rev William Ellis (1794 –1872) as a missionary<br />

in the South Seas and Madagascar was well known, but it was his<br />

contribution in relation to Madagascar through his published writing<br />

and photography, which cemented his reputation for posterity.<br />

In this portrait, he was shown in later life as a somewhat sombre<br />

gentleman sporting a chin-muffler beard, with no other visible<br />

attributes to attest to his character and achievements, but it is perhaps<br />

this lack of decoration which is the best indication of his status<br />

as a missionary and thinker. In contrast, the portrait of the banker<br />

and philanthropist Lord Alexander Peckover, the most eminent of<br />

the Quaker family of Peckovers of Wisbech, shows him as an equally<br />

serious individual. However, the red robes attest to his socially elevated<br />

status not just in Wisbech, but in the nation.<br />

18

Thomas Clarkson (1760-1846), the leading English abolitionist<br />

and campaigner against the slave trade in the<br />

British Empire, and later in the Americas, was undoubtedly<br />

the most illustrious son of Wisbech. As such he was<br />

commemorated by the commissioning of the public<br />

monument to him that still stands in Bridge Street<br />

in the centre of Wisbech.<br />

Clarkson won the fi rst prize in an essay competition<br />

whilst at the University of Cambridge with<br />

his Essay on The Slavery and Commerce of The<br />

Human Species, Particularly the African, 1785.<br />

This is generally regarded as the starting<br />

point of his lifetime’s work. When slavery<br />

was fi nally abolished in the British Empire<br />

with the act of Parliament in 1833,<br />

Clarkson continued to campaign for its<br />

abolition across the world.<br />

“…But this is suffi cient. For if liberty<br />

is only an adventitious right; if men<br />

are by no means superior to brutes; if<br />

every social duty is a curse; if cruelty<br />

is highly to be esteemed; if murder is<br />

strictly honourable, and Christianity<br />

is a lie; then it is evident, that the African<br />

slavery may be pursued, without either<br />

the remorse of conscience, or the imputa-<br />

tion of a crime. But if the contrary of this is<br />

true, which reason must immediately evince, is<br />

evident that no custom established among men<br />

was ever more impious; since it is contrary to<br />

reason, justice, nature, the principle of law and<br />

government, the whole doctrine, in short of<br />

natural religion, and the revealed voice of God.”<br />

— fi nal page of Clarkson’s essay<br />

19<br />

George Gilbert Scott RA: Thomas Clarkson, 1880-81, Stone. Wisbech Town Council.

The monument to him, paid for by public subscription and a large<br />

donation by the Peckover family, was commissioned from Sir<br />

George Gilbert Scott RA (1875). His original design was adapted<br />

into the form that we see today. Work began in 1880 culminating<br />

with the unveiling of the monument on 11 November 1881 by<br />

Sir Henry Brand, Speaker of the House of Commons and MP for<br />

Cambridgeshire.<br />

The fact that the neo-Gothic style of the monument closely resembles<br />

the Albert Memorial in Hyde Park, which Scott designed in<br />

1876, is a clear sign of Clarkson’s importance and eminence. Apart<br />

from the larger than life-size statue of Clarkson holding the manacles<br />

of slavery that he had symbolically helped to remove, standing<br />

under a canopy that rises above him like a spire, there are four<br />

panels below him. Three of these panels are in the form of low relief<br />

sculptures representing William Wilberforce, Granville Sharp, and<br />

perhaps most poignantly, a manacled slave in an imploring attitude.<br />

The fourth panel contains the dedication to Clarkson.<br />

Thomas William Foster was appointed the first resident curator in<br />

1841 when the museum was still located in the Old Market. He<br />

helped to increase the collections of the Museum to such an extent<br />

that five years later, a plan was put in place to erect a purposebuilt<br />

Museum alongside a new building for the Literary Society on<br />

a piece of land adjoining the churchyard of St Peter and Paul, which<br />

the Literary Society had purchased from a Mr Hardwicke. The new<br />

museum and literary Society building were designed by the architect<br />

Mr Buckler of London, and the building was erected for a cost of<br />

£2,405, the cost of which was met by the issue of hundred shares of<br />

£25 each. The new museum opened on July 27, 1847. Foster continued<br />

to be the curator until 1874.<br />

This portrait of him, in keeping with the fashion of the time, is relatively<br />

plain, and he is shown dressed as a gentleman should be. The<br />

most interesting detail is almost invisible in the lower left-hand side<br />

of the painting: books on natural history and an example of taxidermy.<br />

The stuffed bird and the books point to the primary interest<br />

of the curator and remind us that the museum’s collection at this<br />

20

21<br />

Thomas William Foster, First Curator of Wisbech Museum, Detail, 1893, Oil on Canvas.

Balding A: Wisbech Marketplace, During a Festival (Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, 1887?), Detail, Oil on Canvas.<br />

22

period comprised largely of items of natural history and geology<br />

alongside curiosities such as the largest swordfish ever captured<br />

which was 25 feet long, and weighed 5 tonnes.<br />

…to everyone<br />

The subject matter of the works painted by the Impressionists in<br />

the latter part of the 19th century almost exclusively focused on<br />

the bourgeoisie, the new middle-class emerging in France. The two<br />

examples: Édouard Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère; and Georges<br />

Seurat’s Bathers at Asnières, are shown here as a reminder of their<br />

subject matter of ‘modern life’. A barmaid and her customer in a<br />

contemporary music hall bar, or the boys and the tradesmen relaxing<br />

or swimming on the banks of the river Seine at Asnières, subject<br />

matters which were the complete opposite of the academic works<br />

shown at the annual Salon in Paris.<br />

The rapid evolution of photography from experimental practice to<br />

the invention of the Daguerreotype in 1839 by Louis-Jacques-Mande<br />

Daguerre, and the emergence of photographic studios, meant that<br />

by the 1850s almost anyone could have a portrait photograph taken.<br />

The continuing development of the photographic process and the<br />

invention of new types of cameras as well as paper film by George<br />

Eastman in 1885 and later celluloid film (1888 – 1889) accompanied<br />

by his first camera, the ‘Kodak’, in 1888, meant that ordinary people<br />

were empowered to take their own photographs.<br />

This democratisation of the fixing of an image, in other words making<br />

the tools required for creating photographic images available to<br />

almost anyone for a small cost, resulted in the empowerment of<br />

the ordinary person, hence placing the creation of a portrait in the<br />

hands of all. The introduction of colour film in the 1930s completed<br />

this process, and for much of the 20th century film-based photography<br />

reigned supreme.<br />

The invention of the digital camera by Stephen Sassoon an engineer<br />

at Eastman Kodak in 1975 and its rapid development resulting in the<br />

23

introduction of the digital camera phone by Sharp in 2000; the Sony<br />

Ericsson Z1010 and the Motorola A835 in 2003, completed this<br />

process which today means that almost all mobile phones have an<br />

integrated digital camera. Consequently, anyone who owns a mobile<br />

phone today is also in fact a photographer able to create a portrait<br />

or a self-portrait or a group portrait, or indeed any kind of portrait.<br />

The career of Lilian Ream (1877 – 1961) is uniquely associated with<br />

Wisbech and the people of Wisbech, with many of her photographs<br />

being portraits of Wisbech residents. The Lilian Ream Collection<br />

(originally acquired by Cambridgeshire Libraries in the 1981), is now<br />

looked after by a Trust (founded in 1993). It has in its collection<br />

upwards of 150,000 negatives, unfortunately many of these are<br />

deteriorating - a natural consequence of the materials used to make<br />

film - and the process of conservation is slow and time-consuming.<br />

The self-portrait and the selfie<br />

The self-portrait as a category of portraiture is unusual in one<br />

sense, in that the creative artist also becomes the subject of his or<br />

her creativity. It is also unusual in the commercial sense, in which<br />

typically portraits were commissioned from artists by patrons for<br />

payment, yet in this form, the artist is the patron, and therefore<br />

cannot gain any payment out of the activity. And finally, it’s unusual<br />

in terms of the processes and tools that have to be used in order<br />

to create the self-portrait. A reflective surface in which to study<br />

your own appearance is a prerequisite for the painter, therefore<br />

until the successful production of mirror glass, the artist had to rely<br />

upon the reflection on a polished surface or a liquid in order to<br />

gauge their own appearance. The advent of photography made this<br />

process much easier, but even in the early days of photography, it<br />

still required an assistant to control the exposure of the prepared<br />

plate. The development of the portable camera made it easier to<br />

take photographs by one and all, but the self-portrait was still a hit<br />

and miss affair, as the photographer could not be both in front of the<br />

lens and behind the camera’s viewfinder. It is only with the advent<br />

24

of the mobile phone with a front facing camera that the self-portrait<br />

has been achievable by everyone.<br />

Being able to create a self-portrait, by possessing the necessary<br />

tools, is not the same as making a portrait that can convey more<br />

than just the physical appearance of the subject. As a work of art,<br />

the self-portrait, does more than just represent appearance, it also<br />

conveys ideas about the self-image, character, and values of the person<br />

represented.<br />

Early examples of the self-portrait such as that by Albrecht Durer<br />

painted in early 1500 just before his 29th birthday (Alte Pinakothek),<br />

is an extraordinary example of the way in which this particular form<br />

of the portrait can be used and manipulated by the artist to make a<br />

very powerful statement about their appearance, status, personality<br />

and character. Unashamedly, Durer represents himself in an almost<br />

blasphemous manner looking like the image of Christ.<br />

Unlike the self-portrait by Rembrandt painted in 1660 or the selfportrait<br />

of Vincent van Gogh painted in 1889, Durer’s work is<br />

bombastic, all about self-advertisement, and youthful pride in his<br />

own skills and abilities, whereas they are all about introspection,<br />

questioning, and self-reflection.<br />

Through painterly techniques and the use of colour, as well as the<br />

careful build-up of texture, surface and light, Rembrandt turns his<br />

self-portrait into a study of old age, change of fortune, social and<br />

personal isolation, which goes beyond being a mere likeness of him.<br />

More than 200 years later Vincent van Gogh was doing something<br />

similar with new techniques of brushwork, new colours, and a new<br />

use of light, but he too appears equally as introspective and isolated.<br />

Day Shuker’s self-portrait continues this tradition of making the<br />

portrait do more than just represent the physical appearance of the<br />

person. If her technique is a little too dependent on earlier forms<br />

of avant-garde art, the result is still interesting because it forces us<br />

to look beyond the surface of appearance and consider the reality<br />

of the artist.<br />

25

The Library<br />

26

Wisbech prison records<br />

The prison in Wisbech, designed by the architect George Basevi in<br />

1843/44 and referred to as a new house of correction, was described<br />

by one observer as not being of great architectural effect, but providing<br />

satisfaction by the excellent arrangements. The prison in Gaol<br />

Lane (now Victoria Road) was demolished in 1878 in response to<br />

the provisions of the Prisons Act of the previous year because it<br />

had just 43 cells, although records indicate that the cells were often<br />

used to house four or more prisoners.<br />

The survival of two volumes of the prison records covering the<br />

periods 1870 to 1878 provide an insight into the nature of crime in<br />

Wisbech as well as the background, age, profession and character<br />

of the criminals. The fact that the term ‘offender’ meant something<br />

different, and that prison sentences were handed out to persons as<br />

young as 10 years old for a minor crime such as taking some handkerchiefs,<br />

is disturbing to us today. However, that which is perhaps<br />

more disturbing is to see the photographs of these individuals contained<br />

in these prison records, who unlike our stereotypical image<br />

of the ‘mugshot’, are posed as if they had gone to the photographer<br />

to have their photograph taken, sometimes seen in their best<br />

clothes, sometimes in their working clothes, and sometimes in rags.<br />

The primary reason for taking photographs of offenders was due<br />

to an initiative taken by the governor of Bedford prison in the<br />

27

1850s, Robert Evan Roberts, who became concerned that too many<br />

habitual criminals were getting away because the police relied on<br />

written descriptions to help them capture criminals. He decided to<br />

commission a photographer to take pictures of offenders, so they<br />

could easily be traced if they committed further crimes. This practice<br />

very quickly became widespread throughout the penal system<br />

and of course, is still in use to this day.<br />

The images of the prisoners are displayed here as social documents,<br />

without any prejudice to them as human beings, for whatever their<br />

crimes were, they were being judged by a different set of values.<br />

Those Victorian values did not distinguish between the actions of<br />

children, adults or the aged, the poor or the wealthy. They were all<br />

punished according to a severe penal code, which saw fit to handout<br />

periods of hard labour, being condemned to years in a reformatory,<br />

being transported or executed, to young and old without distinction<br />

or mercy.<br />

Rev William Ellis photographs of<br />

the Royal family of Madagascar<br />

In the middle of the nineteenth century, the island of Madagascar<br />

was the object of British and French ambitions, and the situation<br />

was further complicated by Queen Ranavalona’s dislike of European<br />

Christian influences. So, it was only on her death in 1861 that<br />

William Ellis was able to establish his position with the new King<br />

Ramada II who was much more open to the presence of Christian<br />

missionaries in Madagascar. He started to photograph the Royal<br />

family but he saw photography as a means of record rather than<br />

of exerting European superiority. He had been trained by Roger<br />

Fenton, a leading member of the Royal Photographic Society, one of<br />

whose subjects was portraits of the British Royal Family which might<br />

explain the poses and costumes of Ellis’ Malagasian royal portraits.<br />

This was how he thought royalty should be portrayed rather than<br />

a conscious attempt to force European values on the Malagasians.<br />

28

29<br />

Ellis W: Radama II, King of Madagascar, Age 34, Detail, 26 Sep1862, Photograph.

Charles Dickens’ Great<br />

Expectations and fictional portraits<br />

Charles Dickens’s manuscript of Great Expectations, gifted to his<br />

friend Chauncey Hare Townshend and bequeathed by him to the<br />

museum, is an extraordinary autograph document which provides<br />

insights into the writing practices of this author of the Victorian<br />

world. The corrections, the deletions, the overwriting, the pasting<br />

of additional paper, the testing out of different outcomes to events,<br />

all demonstrate this organic process of creative writing.<br />

Out of this autograph manuscript emerges the imagination of the<br />

creative artist who, calling upon his own experience of the world,<br />

his observation of people and the circumstances in which they live,<br />

invents new characters who came to dominate the imagination of<br />

his readers as much in his own day as today. The very fact that we<br />

can instantly summon up the main characters from this novel, is<br />

in part the result of our exposure to the contribution of the cinema<br />

and television, but entirely due to the creative imagination of<br />

Dickens who made these fictional characters real.<br />

The descriptions of them, of their appearance, of their actions, of<br />

the environments in which they lived, all contribute to the evocation<br />

of an actual person before us. When we first meet Miss Havisham<br />

of Satis House, Dickens through the eyes of Pip straining to see in<br />

the gloom of her self-imposed seclusion, allows us to see in physical<br />

form the impact of her unhappy experience as a jilted bride. Her<br />

tattered wedding dress, the decay of her wedding banquet, her<br />

semi-invalid condition, draw our attention and fix it in a manner<br />

which enables us to see through the neglect to the inner desperation<br />

and desolation of this person.<br />

30

31<br />

F A Fraser: The Works of Charles Dickens, Household Edition, Chapman & Hall, Engraving.

The Library<br />

Annexe<br />

32

Portrait of Emperor Napoleon I<br />

in his Coronation robes<br />

François Pascal Simon, Baron Gérard (1770 – 1837), who painted<br />

the original version of this painting now at Versailles, was born in<br />

Rome, where his father was employed in the house of the French<br />

ambassador, was trained in Paris in the studios of leading artists of<br />

the day including Jacques-Louis David.<br />

He achieved artistic success with his portraits, which were displayed<br />

at the annual Salon, notwithstanding the competition with other<br />

artists of the day such as Anne-Louis Girodet de Roucy-Trioson,<br />

whose studio was also responsible for producing original portraits<br />

of Napoleon and making many copies of them. This success at the<br />

Salon brought him to the attention of Napoleon who probably commissioned<br />

this particular portrait.<br />

These portraits of Napoleon form part of a strategy of propaganda<br />

which accompanied his military career and then as Emperor. This<br />

explains their number and proliferation through official copies which<br />

were commissioned to be distributed around the French Empire.<br />

The present work may have been produced in the studio of Gérard<br />

or commissioned as a copy from another studio. The large number<br />

of copies of this works held in collections in Europe and America<br />

suggests that there was an established process for their reproduction<br />

which in turn points to the existence of a sophisticated<br />

machinery for propaganda.<br />

Apart from commissioning numerous copies of the original work<br />

by Gérard for distribution to prominent officials and his own family,<br />

in 1808, Napoleon ordered the imperial tapestry works to make<br />

a full size woven copy of this portrait. The tapestry is now in the<br />

Metropolitan Museum in New York.<br />

The image was also reproduced by other methods and even appears<br />

in a work by the English artist and engraver George Cruickshank<br />

33

(1792 – 1878) which was published in 1828 in volume 3 of The Life of<br />

Napoleon Bonaparte by William Henry Ireland.<br />

The work, apart from representing the event itself and therefore<br />

acting as a record, is primarily a piece of imperial propaganda in<br />

which the symbols of Napoleon’s regime are very clearly employed<br />

in order to suggest the aggrandized status of the Emperor of the<br />

French. The key symbols are represented by the Imperial Eagle at<br />

the top of the staff that he holds, and the Christian Orb lying next<br />

to the Hands of Justice on the stool. His golden headdress of olive<br />

leaves, and the white silk gown under the velvet robe trimmed with<br />

ermine and decorated with golden bees (which are repeated in the<br />

carpet beneath his feet), all attest to his imperial status and the<br />

fact that he was consciously comparing himself to the holy Roman<br />

Emperor Charlemagne, and his predecessors in imperial Rome, as<br />

well as the tradition of European monarchy. With this in mind is perhaps<br />

not surprising that this work was reproduced in large number<br />

in order to propagate the message of Napoleon’s imperial status.<br />

Busts by Pellegrino Mazzotti<br />

Pellegrino was born in Coreglia, Lucca, Tuscany in 1793/5, he died<br />

at the workhouse in Wisbech on 22 October 1879. From the 1810s<br />

onwards he worked and lived at various times in<br />

Norwich, Ely, Lynn, Cambridge, and Wisbech.<br />

When he moved to England in the 1810s he was<br />

following an established path already trodden by<br />

other Italian plaster fi gure makers who came<br />

to England to work. His training had taken<br />

place in Coreglia where his family owned one<br />

of the workshops making plaster fi gures.<br />

His fi rst destination was Norwich, and it<br />

was here that he set up his workshop and in<br />

February 1822 he married Mary Leeds with<br />

whom he had four daughters. Economic<br />

34

circumstances forced him to travel to gain commissions, and it was<br />

perhaps this that motivated him to donate some of his works to<br />

the newly founded Wisbech Museum in 1842. During this period,<br />

he appears to have moved around between Norwich, Wisbech,<br />

Ely, and Cambridge. He returned to Wisbech in 1854 where he<br />

is recorded as a resident in the 1861 and 1871 census returns. In<br />

the latter years of his life fell into poverty and died in the Wisbech<br />

workhouse on the 22 October 1879. His death was announced in<br />

the Wisbech Telegraph of Saturday, 25 October 1879.<br />

1. Plaster bust of the Rev. Henry Fardell, first President of<br />

Wisbech Museum. Made by Mazzotti, Norwich, 1854.<br />

2. Plaster bust of Professor Poison, by Mazzotti, Norwich.<br />

Given by Mr Mazzotti 6.3.1855.<br />

3. Plaster bust of Thomas Clarkson, the anti-slavery<br />

Campaigner, by P. Mazzotti, Norwich 1855.<br />

4. Plaster bust of William Shakespeare; by P. Mazzotti,<br />

Norwich (pictured bottom left).<br />

35

Williamson J: Chauncy Hare Townshend, Detail, 1869, Oil on Canvas.<br />

36

The portrait on the left is of Chauncy Hare Townshend, who gave his<br />

substantial collection of artefacts to the museum, including the Dickens<br />

manuscript of Great Expectations.