Vaughan_book

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

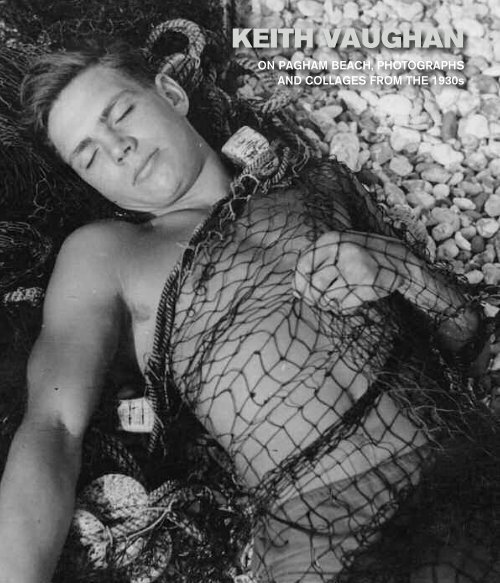

KEITH VAUGHAN<br />

ON PAGHAM BEACH, PHOTOGRAPHS<br />

AND COLLAGES FROM THE 1930s

KEITH VAUGHAN<br />

ON PAGHAM BEACH, PHOTOGRAPHS<br />

AND COLLAGES FROM THE 1930s<br />

Austin / Desmond Fine Art<br />

Pied Bull Yard, 68/69 Great Russell Street, London WC1B 3BN<br />

+44(0)20 7242 4443<br />

austindesmond.com

2

Philip Wright<br />

Keith <strong>Vaughan</strong>: the Pagham photographs<br />

This essay draws unashamedly, and with grateful acknowledgement, on five principal publications:<br />

the artist’s own Journal & drawings (edited by Alan Ross), Malcolm Yorke’s monograph Keith<br />

<strong>Vaughan</strong>: his life and work, Emmanuel Cooper’s Fully exposed: the male nude in photography,<br />

Philip Vann and Gerard Hastings’ monograph Keith <strong>Vaughan</strong> and Gerard Hastings’ Keith <strong>Vaughan</strong>:<br />

the photographs. This last publication and that author’s subsequent <strong>book</strong> Awkward artefacts: the<br />

‘erotic fantasies’ of Keith <strong>Vaughan</strong> illustrate how much of <strong>Vaughan</strong>’s work, both seen and possibly<br />

still unseen, was left behind in the artist’s studio and house after his death. Some of this work<br />

has since been sold, otherwise dispersed, or given to named and possibly also to unnamed<br />

friends. Other materials that are known to exist, such as the artist’s ‘Manual on masturbation’,<br />

may be unlikely to find an official publisher. However, a further substantial and valuable collection<br />

of drawings, photographs, prints and commercial design and illustration projects has also been<br />

assembled by the University of Wales Art Gallery at Aberystwyth, to which we are grateful for<br />

having been given access.<br />

previous page, inside front cover:<br />

Floating boy [P21] (detail)<br />

printed on postcard paper<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

The contents of this exhibition came from the great-nephew of Tracy, formerly Bernard, Stamp 1 –<br />

doubtless an acquaintance or possibly a friend of the artist – and perhaps gifted to Bernard in<br />

the late 1960s after Alan Ross’ publication of the edition he had prepared of the artist’s journal.<br />

A few of the ‘Pagham photographs’ in our exhibition were – daringly, at that date – included in<br />

Ross’s <strong>book</strong>, in which it was also noted that the collection of photographs that had been given to<br />

the printer, the Shenval Press, were never returned, and were therefore presumed lost. 2 Whether<br />

the collection here is, or mirrors, that lost collection, is unclear. The majority of the photos, printed<br />

on postcard material that was commonly available to photographers at that time, do not seem to<br />

have appeared in publications on the artist up till now. 3 While the author of the photographs<br />

cannot be in doubt – this collection contains a few of the six photographs published in the<br />

Journal & drawings – whether they are ‘original’ prints by <strong>Vaughan</strong> himself cannot be proved<br />

beyond a doubt. However, the existence within the set of a couple of different exposures of the<br />

same image, and some proposed croppings drawn in pencil on a few of the images, suggest the<br />

artist’s hand at work. 4 Furthermore, the flimsy black-painted cardboard box containing the collection<br />

of photographs would appear to be hand-made and was clearly labelled in the artist’s hand 5 .<br />

previous page:<br />

Self Portrait [P26]<br />

printed on postcard paper<br />

13.8 x 8.7 cm<br />

left:<br />

Dick (solarised) [P1]<br />

photographic print on Agfa Brovira paper<br />

30.2 x 25 cm<br />

NOTES<br />

1 Bernard Stamp became only the second person in Britain to undergo a sex change in 1952.<br />

2 Gerard Hastings, Keith <strong>Vaughan</strong>: the photographs, Pagham Press, 2013, p. 81.<br />

3 Hastings, ibid., p. 82.<br />

4 see cat. nos. P1, P15 and P32.<br />

5 see back cover.<br />

3

4

I<br />

Until the successful passage of the Sexual Offences Act in 1967, decriminalizing homosexual<br />

acts in private between two men, both of whom had to be 21 or over – a full thirteen years after<br />

the Conservative government had first asked a department committee chaired by John<br />

Wolfenden to give fresh consideration to the law relating to homosexuality and prostitution –<br />

homosexual acts between consenting adults, even in private, had been illegal and were<br />

therefore liable to criminal prosecution. It had taken more than eighty years for section 11 of<br />

the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1885, introduced by Henry Labouchère after a series of<br />

tabloid-magnified ‘scandals’, to be abolished. Section 11 prescribed up to two years<br />

imprisonment with or without hard labour for ‘gross indecency between males in public or in<br />

private’. It was this that would be inflicted, for example, with tragic consequences on Oscar<br />

Wilde and, much later, used to persecute the gifted mathematician Alan Turing, driving him to<br />

suicide.<br />

For <strong>Vaughan</strong>, as for the majority of homosexuals for most of the twentieth century – with the<br />

exception of those at the very top and bottom of the social scale – life was lived between two<br />

worlds: the exterior world of social conventions, heterosexual marriage and procreation, and the<br />

interior world of discreet glances, of furtive and dangerously fraught encounters for sex, of fear<br />

of discovery and shame of prosecution for emotional needs and desires. Of a school-time<br />

friend, <strong>Vaughan</strong> later recalled: ‘I learnt from him the fear, tension and repression that<br />

surrounded everything to do with sex’ 1 . This is not the place to attempt any deeper analysis of<br />

<strong>Vaughan</strong>’s persona or psychological make-up in his early years, but while his own occasional<br />

brief reminiscences in his Journal shed light on his shyness and self-doubt, others’ perceptions<br />

of him at this time indicate how he coped, as many closeted homosexuals did then, by<br />

projecting a different, more insouciant persona. He had apparently been lonely, reserved, and<br />

inevitably bullied at his school, and he later wrote that for him his time at Christ’s Hospital<br />

School had merely represented ‘eight years of concrete misery and romantic reveries’, 2 and that<br />

the experience had left him ‘with a lasting fear of hostility in others, a mistrust of strangers, and<br />

a maddening desire at all costs to ingratiate myself and earn the goodwill of everyone, however<br />

much I might secretly dislike and despise them’. 3<br />

Male portrait behind fishing net [PL7]<br />

photographic print on unmarked paper<br />

30.2 x 25.2 cm<br />

<strong>Vaughan</strong>’s father had abandoned the family when the boy was about eight years old. <strong>Vaughan</strong><br />

remained close to his mother, living in the same house until the end of the 1930s. Yorke and<br />

others have wondered whether the disappearance of his father before <strong>Vaughan</strong> was ten years<br />

old, and the need to protect his overly timid younger brother Richard (known as Dick) in his<br />

early years, may have cast him in the role of a father figure to younger men. 4 With the exception<br />

of the affair he began with Harold Colebrook (whose aunt had the converted railway carriage at<br />

Pagham beach, where most of the photographs in this exhibition were taken) and with whom<br />

he shared many cultural interests, <strong>Vaughan</strong> was quite openly attracted to younger workingclass<br />

men with a rough edge, such as Len and his brother Stan, the grocer’s boy Percy Farrant,<br />

and in later years, the sometime boxer and small-time criminal Johnny Walsh – all of whom<br />

would at one time also model for him to photograph.<br />

5

<strong>Vaughan</strong>’s mother had been educated in a Belgian convent, and spoke both French and<br />

German, as well as English. Both Keith and his younger brother Dick would also master French<br />

and German, going to stay with family friends, the Bellingers, in Berlin in 1930, three years<br />

before Hitler came to power, and once again before the outbreak of war in 1939. Keith would<br />

travel alone to Paris, Cassis and Toulon in 1937, the year of the Paris World Fair. 5 At this Fair<br />

the most monumental pavilions, those of Hitler’s Germany and Stalin’s Russia, memorably<br />

confronted each other, and the Spanish Republic’s pavilion famously housed Picasso’s Guernica,<br />

as well as major works by Miró and Calder. It is not known, however, whether <strong>Vaughan</strong> actually<br />

visited the Fair. In 1938 the family also spent Christmas in Austria (after Hitler had been<br />

enthusiastically welcomed back in his homeland). What effect these travels and experiences<br />

had on the artist is nowhere recorded.<br />

One year after leaving school, <strong>Vaughan</strong> joined Lintas (Lever International Advertising Services),<br />

the recently re-branded advertising department of Unilever, which up till then had been mainly<br />

tasked with purchasing advertising space rather than designing its own advertisements. 6 The<br />

task was now to work on promoting its own toiletries and cooking fats. It is not recorded<br />

precisely how or why <strong>Vaughan</strong> entered this agency, but with the Depression and unemployment<br />

levels growing in severity by 1931, several young artists of promise such as Graham Sutherland,<br />

John Piper and John Banting would take up commissions or employment in advertising during<br />

that sombre decade.<br />

The practice of using art for advertising was of course not new, though it had been somewhat<br />

haphazardly exploited towards the end of the previous century; with Toulouse-Lautrec and Jules<br />

Chéret, for example, in France, or the Beggarstaff Brothers (William Nicholson and James<br />

Pryde) in Britain. In 1889 William, later Lord Lever purchased William Powell Frith’s latest<br />

painting The New Frock 7 at the Royal Academy, which he used as a poster image to advertise his<br />

Sunlight Soap – tag-line ‘So clean’ – much to the artist’s disgust. Around 1900 his American<br />

business partner Sidney Gross would also employ well-known magazine illustrators such as Phil<br />

May, Lawson Wood and the Punch cartoonist Bernard Partridge to promote Lever Bros.<br />

products. However, Len Sharpe, the compiler of The Lintas Story, has explained that ‘the artists<br />

of the 20s were unapologetically commercial men, not fine artists allowing their creations to be<br />

used for commercial purposes’. 8 So much so that in 1934 the artist Leon Underwood would<br />

characterize commercial art as employing ‘cache-toi aesthetics to tell magnificent lies about<br />

commodities’ 9 – in Lintas’s case, soaps and margarine.<br />

Sharpe went on to write that ‘The Lintas staff, located in Unilever House, were conspicuous<br />

among the other occupants of that rather solemn and majestic headquarters. They dressed and<br />

behaved as the whim took them. There was the sandaled and sockless visualizer who struck a<br />

bizarre note among the dark suits and umbrellas in the Unilever elevators. Sometimes outbursts<br />

of exuberance during office hours scandalized the managers of more formal departments who<br />

could observe these carefree antics across the well of the great building.’ 10<br />

It seems that as a trainee layout artist 11 <strong>Vaughan</strong> joined a team with diverse skills and interests,<br />

a few of whom would remain friends for many years after the artist had left Lintas. They<br />

included an Australian, John Passmore, and a New Zealander, Felix Kelly, both of whom were<br />

trained artists with exhibiting careers. It was another trained artist-member of the Lintas team,<br />

Reg Jenkins, who, seeing <strong>Vaughan</strong>’s interest in photography, persuaded him to buy a Leica<br />

6

A male figure kicking, draped in wet cloth [P1]<br />

printed on postcard paper, with pencil marking<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

Boy in fishing net [P3]<br />

printed on postcard paper<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

Len with towel [P2]<br />

printed on postcard paper<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

Boy holding up fishing net [P4]<br />

printed on postcard paper<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

7

Ballet rehearsal No.4 [BR4]<br />

printed on postcard paper<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

camera, with which he would over the years shoot ‘hundreds of feet of camera roll’, notably at<br />

the ballet and at Pagham beach. It appears that <strong>Vaughan</strong> had started to take photographs with a<br />

medium-format reflex camera while still at school. By 1932 he had installed his own darkroom<br />

in the family home, which he would also be able to use as a studio setting for photographing his<br />

young models. It isn’t known what model of Leica he purchased, as it was stolen sometime after<br />

1939 and he never replaced it.<br />

Although a prototype Leica using 35 mm film had been produced before World War I, the Leica<br />

model I would not go into production before 1925. Model II appeared in 1932, now with a builtin<br />

rangefinder and a set of interchangeable lenses. It was this model that the likes of Cartier-<br />

Bresson, André Kertész and Leni Riefenstahl would use. Andreas, the son of the painter and<br />

Bauhaus teacher Lyonel Feininger, published Menschen vor der Kamera, the first detailed<br />

manual for 35 mm photography in 1934, which was followed by Theo Kisselbach’s Il Libro della<br />

Leica in the following year. The popularity of the camera was greatly enhanced by Paul Wolff’s<br />

sequence of publications, which first appeared in German and were issued almost immediately<br />

in four other language editions; in England as My first ten years with the Leica in 1934, What I<br />

saw at the 1936 Olympic Games in the same year, and Work! in 1937. Whether <strong>Vaughan</strong> had<br />

seen or possessed any of these is not known, though with his interest in photography, his use of<br />

a Leica and his knowledge of German, it is more than possible.<br />

His friend John Passmore later reminisced about <strong>Vaughan</strong>’s ‘vivacity, his love of music [<strong>Vaughan</strong><br />

was an accomplished pianist] and his wonderful mobility while dancing … it was such a brilliant<br />

thing. He was very close to a Diaghilev dancer’. 12 Passmore might have been referring to the<br />

prima ballerinas Toumanova or Danilova, whom <strong>Vaughan</strong> had befriended, once taking the former<br />

down to Pagham beach with his friends. 13 Presumably it was this very friendship with the prima<br />

ballerinas that had enabled <strong>Vaughan</strong> to attend, and then to photograph, some ballet rehearsals<br />

[see cat. no. BR4]. He was also able to take some photographs of live performances from the<br />

far sides of the stalls or circle, at least one of which is known to have been included in a 1930s<br />

<strong>book</strong> on ballet, 14 and others which he appears to have produced for sale in the same postcard<br />

format as the Pagham beach photographs. 15<br />

In July 1929 <strong>Vaughan</strong> had gone with his mother to Covent Garden to see what proved to be<br />

Serge Diaghilev’s last production for the Ballets Russes, Prokofiev’s Le Fils Prodigue, with the<br />

Standing nude model [PL2]<br />

photographic print laid on card<br />

30.2 x 20 cm (photograph),<br />

30.2 x 25 cm (card)<br />

8

9

Boy under beached ship hull [P5]<br />

printed on postcard paper<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

Young man lying on cot [P7]<br />

printed on postcard paper<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

Two male figures, one throwing [P6]<br />

printed on postcard paper (inverted)<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

Male nude on white rocks [P8]<br />

printed on postcard paper, indistinct pencil inscription verso<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

10

Boy under beached ship hull II [P9]<br />

printed on postcard paper, inscribed in pencil verso ‘Sily(?) Solo’<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

Boy under beached ship hull III [P11]<br />

printed on postcard paper (inverted)<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

Len with towel II [P10]<br />

printed on postcard paper, with pencil marking<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

Young man at water’s edge with raised arm [P12]<br />

printed on postcard paper<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

11

Dick <strong>Vaughan</strong> [P13]<br />

printed on postcard paper<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

A young man beside a corrugated shed, holding oars [P28]<br />

printed on postcard paper, inverted<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

Dick <strong>Vaughan</strong> holding dead branch [P42]<br />

printed on postcard paper (inverted)<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

Fishing boats [P59]<br />

printed on postcard paper, inverted<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

12

lead danced by Serge Lifar, and striking sets designed by Rouault. Diaghilev died the following<br />

month. That great impresario had created the male ballet lead, making a star out of Nijinsky and<br />

later Lifar and, by commissioning or bringing together new music scores, new scenery by<br />

contemporary artists and new movements in choreography, had led ballet to become a leading<br />

focus for artistic creativity in the interwar years. The ballet, more even than classical music<br />

concerts, provided a well-known haunt, or at least a less fraught socialising space for homosexuals<br />

– ‘is he musical?’ being one of the codes for hinting at homosexual leanings. It was at the ballet<br />

that <strong>Vaughan</strong> first met Harold Colebrook, and where they both could unashamedly admire the<br />

almost naked athletic figures of the dancers.<br />

Just before the outbreak of war, at the age of 27, <strong>Vaughan</strong> decided to keep a journal. He kept it<br />

up until the very day of his death by suicide almost forty years later. Although he managed some<br />

level of privacy in his locked photographic darkroom in the house, his mother would meet and<br />

entertain his male visitors, and later come to understand the nature of his relationships and yet,<br />

paradoxically, she receives hardly a mention in the published journal. There are no entries in the<br />

Journal before 1940 that mention colleagues from the Lintas office. Yorke gathered information<br />

about <strong>Vaughan</strong>’s socializing with them from later interviews with a few of his former colleagues,<br />

but it is also possible that editing of the Journal by Alan Ross or <strong>Vaughan</strong>’s close friend, the<br />

artist Prunella Clough, prior to its publication may account for some puzzling lacunae.<br />

Introducing Alan Ross’s 1966 edition of his Journal & drawings <strong>Vaughan</strong> wrote: ‘When I began<br />

writing this journal in 1939, it was certainly not with the thought that it might be published and<br />

possibly even read. Its purpose was therapeutic and consolatory’ 16 . By 1972, however, the artist<br />

had decided: ‘The whole purpose of this journal is to reveal myself as fully as possible to future<br />

readers whom I shall never know … I shall write with the intention of being read 17 …. I have not<br />

suppressed opinions I no longer hold, or attitudes of mind which are now embarrassing, if they<br />

seem true of their time.’ 18 His biographer, Malcolm Yorke explained that ‘<strong>Vaughan</strong> believed that<br />

his works would be illuminated if the viewer knew what the artist was feeling, thinking, believing<br />

and suffering at the time he created them.’ 19 However, such was <strong>Vaughan</strong>’s sense of discretion<br />

about others, as opposed to himself and his feelings, that hardly any of his male acquaintances<br />

or friends are mentioned in the published Journal. Nor, surprisingly perhaps, do events of<br />

national or international importance feature in the Journal. Despite <strong>Vaughan</strong>’s choice of<br />

conscientious objection in World War II, there is no evidence that he found the geopolitical<br />

turmoil of this period a source of interest.<br />

Sadly, in the context of interpreting this collection, <strong>Vaughan</strong>’s Journal postdates the decade of<br />

the 1930s when the works in this exhibition were created. An occasional retrospective<br />

reminiscence is all that survives first hand, and these are markedly self-critical. Recalling the<br />

years at Lintas, <strong>Vaughan</strong> wrote ‘the cowlike docility with which I had hung on there for eight<br />

years … lacking the courage to break away … through my fastidiousness and high demands, I<br />

was always frustrated and dissatisfied so I turned inwards’ 20 All too aware of the contradictions<br />

of his existence, he confessed: ‘I refused to submit to the ideas and principles of commerce, but<br />

I worked in commerce. I refused the way of life at home, but I lived at home. I chose my friends<br />

spontaneously and haphazardly from all societies and classes, and so became a stranger in all<br />

societies …’ 21<br />

13

As an aside, it is interesting to note how during the 1930s the ‘eccentric’ behaviour of Cecil<br />

Beaton and his close circle of high-society friends such as the composer Lord Berners, the art<br />

collector Peter Watson, the actor John Gielgud or the artistic, outrageous dilettante Brian<br />

Howard would be tolerated with humour by the public, and even a young left-leaning set around<br />

Auden, Isherwood, Spender and Britten would gain some public respect for their work, but<br />

<strong>Vaughan</strong> does not seem to have had an entrée into either of these homosexual circles. The<br />

Lintas team may have been seen as an ‘eccentric’ group within the conventional norms of the<br />

Unilever workforce, but <strong>Vaughan</strong> could well have been intimidated by the sort of vicious – we<br />

would call it ‘homophobic’ today – reaction that, for example, was met by some critics in 1933 to<br />

a play addressing the theme of homosexuality. Mordaunt Shairp’s The Green Bay Tree featured<br />

as a central character ‘a screaming and thoroughly nasty creature who “corrupts” a young Welsh<br />

boy he has adopted. Even though he gets his just deserts and is murdered at the end, the critics<br />

were in uproar.’ 22 Under headings such as ‘Plays that ought to be burnt’, ‘Play of the abnormal.<br />

Repulsive topic …’ the critic J.C. wrote ‘the whole thing must be repugnant to the normal<br />

individual, and therefore I can only deplore the presentation of this play’, although another critic<br />

conceded the playwright’s skill but could only ‘commend his play to all who do not find his theme<br />

irreparably distasteful’. In the light of the punitive Labouchère amendment, better therefore for a<br />

shy gay man like <strong>Vaughan</strong> to remain closeted, unless one enjoyed a level of fame and<br />

recognition like that of the Beaton set, or the level of acclaim bestowed on intellectuals of the<br />

Auden set.<br />

Such was <strong>Vaughan</strong>’s dissatisfaction with his twenties that he dismissed them as merely ‘years of<br />

dilettantism, piano playing, writing, ballet, reading. There was no system, no real progress.’ 23 In<br />

spite of this, he evidently continued to read widely, including French and German in the original,<br />

as well as other foreign authors in translation. Vann mentions Goethe, Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky,<br />

Chekhov, Proust, Baudelaire, Verlaine, Rimbaud and Mallarmé. 24 Touchingly, in the midst of the<br />

darkest year of the war, 1941, among sketches of human suffering and scenes recording bomb<br />

destruction, <strong>Vaughan</strong> inscribed lines in German from Rilke’s ‘Duineser Elegien’:<br />

‘Nirgends, Geliebte, wird Welt sein, als innen’,<br />

‘Eines ist die Geliebte zu singen. Ein anderes, wehe’,<br />

‘Gib ihm die Nächte Übergewicht – verhalt ihn’, and<br />

‘Die Szenerie war Abschied. Leicht zu verstehen’. 25<br />

These masterpieces of twentieth-century poetry are acknowledged to be difficult fully to fathom,<br />

even in the original German, and virtually impossible to do justice to in translation. <strong>Vaughan</strong>’s<br />

discerning choice of lines hint at love, longing and loss, pain and suffering, and the shrouding<br />

weight of night.<br />

14

Bather and biplane [P14]<br />

printed on postcard paper<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

Bather fastening sandal [P16]<br />

printed on postcard paper<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

A male figure in silhouette holding wet cloth [P15]<br />

printed on postcard paper, with pencil marking<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

Young man at water’s edge [P17]<br />

printed on postcard paper<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

15

Male nude standing beside deckchair [P19]<br />

printed on postcard paper, with pencil marking<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

Young man doing a handstand on deckchair [P49]<br />

printed on postcard paper<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

A male figure walking on a plank [P18]<br />

printed on postcard paper, inscribed in pencil verso ‘Sily(?) Solo’<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

Floating boy [P21]<br />

printed on postcard paper<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

16

NOTES<br />

Between 1939 and 1977 Keith <strong>Vaughan</strong> wrote a total of 61 Journals, from 48 of which Alan Ross made a selection (eleven<br />

years before the artist’s death). Ross edited and published his selection in 1966 at the Shenval Press in Harlow, Essex.<br />

<strong>Vaughan</strong>’s biographer, Malcolm Yorke had access to the complete set of journals, and these are referred to in his<br />

monograph as ‘Journal’, followed by the volume number, page number and entry date; e.g. ‘Journal 4-6, 11 August 1940’, as<br />

also below.<br />

1 Unsourced quotation recorded by Malcolm Yorke, Keith <strong>Vaughan</strong>: his life and work, London 1990, p. 29.<br />

2 Yorke, ibid., p. 32.<br />

3 From an undated manuscript entitled ‘M’s childhood’, quoted by Yorke, ibid., p. 32.<br />

4 Yorke, ibid., p. 26.<br />

5 Its official title was the ‘Exposition des Arts et des Techniques de la Vie Moderne’.<br />

6 Lintas was the agency that launched the first commercial radio programmes from Radio Luxembourg in the early<br />

1930s. Later in that decade it was one of the leading agencies producing its own in-house advertisements for<br />

cinema showing, including the first in colour (for Persil, according to its historian Len Sharpe: see footnote 8 below).<br />

7 Now in the collection of Liverpool’s National Museums.<br />

8 Len Sharpe, The Lintas Story: impressions and recollections, London 1964, p. 18.<br />

9 THIRTIES: British art and design before the war, Arts Council of Great Britain and Victoria & Albert Museum, 1979-80.<br />

10 Sharpe, ibid., p. 52.<br />

11 ‘According to the 1930s thriller by Dorothy L. Sayers Murder must advertise, a new employee [in an advertising<br />

agency] would find that the aim of the studio artist was ‘to crowd the copy out of the advertisement’. The copywriter’s<br />

ambition was ‘to cram the space with verbiage’ and leave no room for the illustration. The layout man ‘spent a<br />

wretched life trying to reconcile these opposing parties’, in Richard Hollis et al., Ashley Havinden: advertising and the<br />

artist, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh 2003, p. 28.<br />

12 Yorke, op. cit., p. 39.<br />

13 See cat. nos. P70 and P71, possibly Toumanova.<br />

14 Yorke, op. cit., p. 47; Cyril M. Beaumont’s Complete Book of Ballets London 1937, p. 880. The collection at the<br />

University Art Gallery of Wales includes 35 photographs of ballet performances, including Le Tricorne with sets and<br />

costumes by Picasso.<br />

15 The postcard size cat. no. P37 bears the inscription ‘2/6’ on the reverse, while the larger print, cat. no. PL11 is<br />

inscribed ‘5/-’, also on the reverse.<br />

16 Keith <strong>Vaughan</strong>: Journal & drawings edited and published by Alan Ross 1966, p. 7.<br />

17 Journal 54-36, 28 January 1972, quoted by Yorke, op. cit. , p. 18.<br />

18 <strong>Vaughan</strong>, ed. Ross, ibid., p. 8.<br />

19 Yorke, op. cit., p. 16.<br />

20 Journal, 4 November 1940, quoted in Philip Vann and Gerard Hastings, Keith <strong>Vaughan</strong>, London 2012.<br />

21 Journal 4-6, 11 August 1940, quoted by Yorke, op. cit., p. 49.<br />

22 Reviews reproduced in James Gardiner, Who’s a pretty boy then?, London (1996).<br />

23 Journal 15-12, 23 May 1943, quoted by Yorke, op. cit., p. 51.<br />

24 Vann and Hastings, op. cit., p. 41.<br />

25 <strong>Vaughan</strong>, ed. Ross, op. cit., p. 55.<br />

17

Man and oil drum [PL3]<br />

photographic print on Agfa Brovira paper<br />

25 x 30.2 cm<br />

18

Young man doing a handstand [P22]<br />

printed on postcard paper<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

Figure swimming in shallow water [P24]<br />

printed on postcard paper (inverted), inscribed in pencil verso ‘Water’<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

Two male figures, one drying his face with towel [P23]<br />

printed on postcard paper<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

Naked male figure on beach, muscular pose [P27]<br />

printed on unidentified paper<br />

9.8 x 13.8 cm<br />

19

A male figure draped full length in wet cloth [P32]<br />

printed on postcard paper with pencil marking<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

Male bather pulling on a coat [P35]<br />

printed on postcard paper (inverted)<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

Len eating a melon [P33]<br />

printed on postcard paper<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

Two male figures one throwing [P37]<br />

printed on postcard paper (inverted), inscribed ‘2/6’ in ink verso<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

20

Two male figures on a beach [PC1]<br />

gouache and photograph on card<br />

30 x 25.5 cm<br />

21

Smiling man with hands on head [PC2]<br />

gouache and photograph on card, small collage of beached boat verso<br />

30 x 25.5 cm<br />

22

Figure lying on beach at night [PC3]<br />

gouache and photograph on card<br />

30.5 x 25.5 cm<br />

23

Male figure seated on wooden breakwater [PC4]<br />

ink, gouache and photograph on card, signed with address top right<br />

30 x 25 cm<br />

24

Four figures on a beach [PC5]<br />

ink and gouache on photograph on card<br />

30.2 x 25 cm<br />

25

Seated naked figure on beach [PC6]<br />

ink, gouache and photographe on card<br />

30.5 x 25.5 cm<br />

26

Male figure seated against sky [PC7]<br />

gouache and photograph on card<br />

30.4 x 25.7 cm<br />

27

Len seated on beach beside deckchair [P38]<br />

printed on postcard paper (inverted)<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

A male figure, drying himself on the beach [P41]<br />

printed on postcard paper, with pencil marking<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

A male figure wearing loincloth standing at water’s edge [P39]<br />

printed on postcard paper (inverted), embossed markings<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

Two male figures in silhouette, one holding wet cloth [P43]<br />

printed on postcard paper, with pencil marking<br />

9.8 x 13.8 cm<br />

28

II<br />

Emmanuel Cooper has explained in his comprehensive study Fully exposed: the male nude in<br />

photography how the choice of the (male) nude as a subject coincided with the birth of photography<br />

itself, as soon as the model could show that s/he could hold the pose for the necessary length of<br />

the camera’s exposure. Not only had many of the first photographers originally studied as artists,<br />

but also they saw photographing the nude as a substitute for, and even an improvement on, the<br />

pose of a living model in the studio. The photograph could offer more realistic, ‘truthful’ varieties<br />

of poses that could be captured and held in permanence. The pioneers in this genre included<br />

Julien Vallou de Villeneuve, Eugène Durieu and Guglielmo Marconi, followed by collections of<br />

naked poses by the likes of Louis Igout and Albert Loude, amongst others. Many of their<br />

photographs would become commercially available in single prints and postcards.<br />

The constant and rapid improvement of cameras and printing techniques throughout the<br />

nineteenth century – portable cameras, faster exposures, cheaper and more durable prints –<br />

released the professional and the amateur from being tied to the studio or having the burden of<br />

moving a cartload of bulky equipment when they worked out of doors. The publication of<br />

Eadweard Muybridge’s scientific study Animal locomotion in 1887 – showing a succession of<br />

split-second photographs of animals and naked human figures in movement – demonstrated how<br />

a camera was able to capture changes in muscular configuration and reveal new truths about the<br />

human body. This in turn stimulated a fresh look at the body’s outward form and its potential for<br />

idealization. Muybridge’s studies were available in multi-volume form, as were other similar<br />

studies of human motion by Étienne-Jules Marey and Thomas Eakins. Many of the Muybridge’s<br />

most successful artist-contemporaries owned a set of his Animal locomotion, such as Rodin,<br />

Gerôme, Bouguereau, Puvis de Chavannes, Whistler, Leighton and Sargent.<br />

Photographing the male nude as an aide for artists had invited parallels with Classical (nude)<br />

statuary, and this in turn led in the late nineteenth century to a cult of body-building to achieve a<br />

perfect male physique that could mirror the statuary of old. Photographic collections of classical<br />

poses, with male nudes occasionally seen as ‘supporting’ architectural motifs, were assembled by<br />

Koch & Rieth, whose Der Akt appeared in 1894, and Émile Bayard, who completed his portfolio<br />

Le Nu esthétique in 1903. Perhaps the most famous of these statuesque posing body-builders<br />

was the Hungarian-born Briton, Eugen Sandow (1867–1925), hailed at that time as ‘the world’s<br />

most perfect man!’ Sandow published his own Journal, exhibiting photographs of his ‘movements’<br />

and ‘poses’, and promoting his own body-building equipment and diet. 1 His <strong>book</strong> Life is<br />

movement, published in Britain in 1918, was sold worldwide, exploiting the vogue for wrestling<br />

and other athletic poses which had been building over the twenty years since the revival of the<br />

Olympic Games in 1896. Sandow also recommended that ‘every physical culturist should own a<br />

camera … the two hobbies form an admirable combination’.<br />

In the second half of the nineteenth century some saw photography as destined to attain the same<br />

status as painting, though others firmly rejected this notion. After the cataclysm of WWI which<br />

affected so many levels of human behaviour, creativity and understanding – and which we might<br />

29

say, with hindsight, was adumbrated in the arts by movements such as Cubism, Expressionism,<br />

atonality in music and ‘parole in libertà’ in poetry – new definitions of the purposes and uses of<br />

photography were to be expected. The 1920s saw photography branching out into the fields of<br />

propaganda and social and political agitation, as well as into new artistic experiments with the<br />

camera, as an aid to scientific investigations, and as the ideal tool to feed the increasing popular<br />

appeal of fashion photography. Amongst artists, photography was also taken up by the<br />

Surrealists for the purpose of provocative anti-rationalism, and by others for the expression of<br />

greater frankness about sexual matters.<br />

During the years of the threat of criminal prosecution under the Labouchère amendment in<br />

Britain, magazines and photographs of the male nude found a place in assuaging some of the<br />

emotional needs and desires of the homosexual fraternity, and in fact naked male and female<br />

‘artists’ photography models’ were openly advertised as available from, for example, an ‘Art Service’<br />

in Liverpool during the interwar years. 2 Germany had led the way with magazines serving the<br />

gay interest, such as Adolph Brand’s Der Eigene (1896–1932) and Otto Bierbaum’s remarkable<br />

but short-lived Der Insel (1899-1901). The Swiss Karl Meier, who first wrote occasionally for<br />

Brand’s magazine in the 1920’s under the pseudonym ‘Rolf’, had returned to Zurich by 1934,<br />

and continued to write for the gay publications Schweizerisches Freundschaftsbanner (1933-<br />

1936) and Menschenrecht (1937-1942), after which he appears to have taken charge of the<br />

latter magazine, publishing it under the title Der Kreis from 1943 onwards. These would be the<br />

only German-language gay magazines to continue publishing during the Nazi period, though of<br />

course not in Germany itself. One should not overlook the circulation, too, of previously<br />

commercially available photographs of naked models described below, albeit clandestinely.<br />

Several earlier cultural and social developments had also contributed to the possibilities for gay<br />

men expressing their sexuality in the 1930s, from which <strong>Vaughan</strong> and other closeted<br />

homosexuals may have benefited.<br />

In spite of Germany’s criminalization of homosexuality in 1871 3 there were active underground<br />

circles which became fairly open in the big cities during the Weimar Republic, especially in Berlin,<br />

whose notorious permissiveness up to 1933 was enjoyed by men like Auden, Isherwood, Spender<br />

and Bacon. Similarly, the openness of Parisian artistic circles to diversity from distinct coteries<br />

around the personalities of, for example, Diaghilev, Picasso, Cocteau and Josephine Baker and,<br />

by contrast, the Gleichschaltung of Austrian society to Nazi homophobic ideology cannot have<br />

passed unnoticed by <strong>Vaughan</strong> on his visits to Germany, Austria and France in the 1930s. Even<br />

in the midst of the war, he would inscribe some of his drawings with quotations from German<br />

poetry, which might have risked drawing his fellow soldiers’ attention to his particular sensibility.<br />

In Germany there had been a recognized tradition of male bonding in the nineteenth century<br />

through the politicized nationalist Burschenschaften and, in a different setting towards the end of<br />

that century, through a revived Wandervogel movement – a version of ‘back to [exploring and<br />

enjoying] nature’, as an escape from the effects of rapid and widespread industrialization across<br />

Germany’s cities. This would give impetus both to the ‘naturist’ movement and to the exaltation<br />

of nudity and, through magazines and photography, to a cult of the naked body, to body-building<br />

and athleticism, and to mass displays of gymnastics.<br />

It would be the pioneering German magazine Der Eigene, mentioned above, that first gave wider<br />

circulation to the new style of ‘aesthetic’ nude photographs of languid pubescent Italian youths<br />

30

Two male figures posing at tug of war [P44]<br />

printed on postcard paper<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

Male figure standing beside rowing boat [P46]<br />

printed on postcard paper<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

Len with a second male on beach [P45]<br />

printed on postcard paper<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

A male figure walking down the beach [P47]<br />

printed on postcard paper (inverted), with ink marking<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

31

y Baron Wilhelm von Gloeden (1856–1931), a German aristocrat who had settled in Taormina<br />

on the island of Sicily before the turn of the century. His photographs, along with those of his<br />

compatriot Wilhelm, aka. Guglielmo, Plüschow (1852–1930), were also issued as postcard<br />

collections, and are known to have been widely distributed across Europe and beyond, as were<br />

photographs of similar subjects by the Italians Vincenzo Galdi and Gaetano d’Agata. At the same<br />

time some photographic studios would strip away Italianate languidness to develop the culture<br />

of the naked (male) ‘pose’ also known as the ‘pose plastique’, depicting naked young men<br />

entangled in a group which often resembled a fragment of a sarcophagus or temple frieze from<br />

ancient Greece. Much later, an Englishman called Laurence Woodford, who garnered the title of<br />

‘The Prince of Pose’, would in 1938 publish his <strong>book</strong> Physical Idealism and the Art of Pose. His<br />

models – wearing the minimal ‘posing pouch’ such as used by some of <strong>Vaughan</strong>’s photographic<br />

subjects – would also appear in well-established and ‘respectable’ body-building or naturist<br />

magazines such as Health and Strength and Health and Fitness. Besides his own photography<br />

of his friends at his studio and at Pagham, <strong>Vaughan</strong> is known to have had collections of similar<br />

photos by others, and of magazines such as the above.<br />

In Germany <strong>Vaughan</strong> might have come across the movements or publications of Adolf Koch or<br />

Major Hans Surén. Surén had been the German Army’s Director of Physical Education for four<br />

years before his dismissal in 1924, whereupon he published his illustrated <strong>book</strong> Der Mensch und<br />

die Sonne followed a year later by his manual for disciplined exercises Deutsche Gymnastik to<br />

promote ‘virile, primitive manhood’. Koch, on the other hand, coming from a Socialist perspective,<br />

advocated naked gymnastics in the open air, with the educational purpose of alleviating the<br />

effects of urban poverty that damaged the health of children and young people. Koch would<br />

eventually organize a widely attended international Congress on Nudity and Education in 1929,<br />

but his work would be banned when the Hitler regime came to power. Whether this was because<br />

of his known Socialist politics, or because he promoted naked school exercises, is unclear.<br />

Illustration from Hans Suren’s<br />

Deutsche Gymnastik<br />

This encouragement of increased physical activity in the open air was matched by a new fashion<br />

for swimming and sunbathing naked. This had already started, for example, at Stockholm’s<br />

swimming baths before World War I. Shortly after the war, Coco Chanel, a leading figure of<br />

fashion, hymned the beauty of bronzed bodies and encouraged sunbathing at fashionable<br />

resorts in the south of France. France saw the launch in 1926 of Marcel Kienné de Mongeot’s<br />

fortnightly naturist magazine Vivre intégralement from within the League for Physical and Mental<br />

Regeneration. In the same year, the American naturist Bernarr Macfadden launched the shortlived<br />

Muscle Builder, followed by his more successful magazine Physical Culture in 1929.<br />

Cooper points out that a difference would soon become evident between ‘naturists’ with their<br />

more philosophical and contemplative enjoyment of being naked in a natural setting in the spirit<br />

of de Mongeot, and ‘nudists’ who admired the sensuality of the naked body for its own sake and<br />

delighted in seeing it or being themselves seen naked in the spirit of Macfadden. Publishing of<br />

these magazines and their photographs, however, still risked prosecution. 4<br />

In the 1920s the genre of a photographic essay or ‘oeuvre’ – in place of the ‘livre d’artiste’, a ‘livre<br />

de photographie’ so to speak – broke new ground with the publication of the likes of Germaine<br />

Krull’s Métal (1928, exploring the engineering structures of the Eiffel Tower and other impressive<br />

metal structures), Man Ray’s Electricité (1931, showcasing his own invention, the ‘rayogramme’)<br />

and Brassaï’s Paris de nuit (1933, revealing an unglamorous and ignored side of Parisian life).<br />

Such publications may have inspired <strong>Vaughan</strong> to assemble his own photographic ‘livres’ – the<br />

Male model posing with<br />

hessian sheet [PL9]<br />

photographic print on Agfa Brovira<br />

paper laid on card<br />

30.2 x 20.2 cm (photograph),<br />

30.2 x 25.2 cm (card)<br />

32

33

Two male figures in silhouette, one draped in wet cloth [P48]<br />

printed on postcard paper<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

A male figure in silhouette half covered in wet cloth [P51]<br />

printed on postcard paper, with pencil marking<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

Pagham Pieta II [P34]<br />

printed on postcard paper<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

Male figure crouching at water’s edge [P52]<br />

printed on postcard paper<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

34

‘Highgate Ponds’ album and, later, his memorial album for his fallen brother, ‘Dick’s Book of<br />

Photographs’. That first postwar decade had also seen the publication of several influential <strong>book</strong>s<br />

on photography such as Moholy-Nagy’s Malerei, Photographie, Film (1925, no.8 of the series of<br />

Bauhaus Books), Albert Renger-Patzsch’s Die Welt ist schön (1928) and Franz Roh’s Foto-Auge:<br />

76 Fotos der Zeit (1929) and El Lissitzsky’s Russland: Die Rekonstruktion der Architektur in der<br />

Sowjetunion (1930), all of which were available in Britain. David Mellor has also drawn attention<br />

to the German lawyer turned photographer Erich Salomon, who was hailed – possibly questionably<br />

– as ‘the world’s first candid cameraman’ when he exhibited at the Royal Photographic Society in<br />

1935. 5<br />

It is known that <strong>Vaughan</strong> admired and owned photographs, amongst others by Man Ray and Bill<br />

Brandt, both of whose work appeared fairly regularly in the leading French cultural publication<br />

AMG (Arts et Métiers Graphiques). This was a fortnightly spiral-bound publication which ran from<br />

1927 to 1939, covering contemporary art, photography, literature and graphic design, and which<br />

proclaimed itself ‘le premier journal moderne d’information par l’image en France’, and was hailed<br />

as ‘une véritable encyclopédie des AMG de l’entre-deux guerres’. AMG also featured the latest<br />

contemporary typography and designs for advertising, so it would not have been out of place in<br />

an advertising agency. However, it is not known whether <strong>Vaughan</strong> saw in Lintas’s office, or<br />

privately, examples of this magazine which also featured, amongst others, work by leading<br />

professional, and known-to-be-gay, photographers such as the Hungarian Emeric Féher, the<br />

Balt George Hoyningen-Huene, the American George Platt Lynes, the Germans Herbert List<br />

and Horst P. Horst, and the Frenchmen Albert Rudomine, Jean Morel and Max Dupain, all of<br />

whom at one time in the 1930s photographed the male nude. 6<br />

It is noticeable that in its published form, <strong>Vaughan</strong>’s Journal does not recall any significant<br />

events of that decade other than a reminiscence of the summer of 1939 ‘before the Soviets had<br />

signed our death warrant’. 7 Colleagues at Lintas had remarked on his lack of interest in politics,<br />

right:<br />

Herbert List<br />

Ritti with fishing rod, 1937<br />

© Herbert List/Magnum Photo’s<br />

far right:<br />

Anonymous portrait of Serge Lifar, undated<br />

35

Male figure beside harbour wall (cut down) [P29]<br />

printed on postcard paper<br />

7.5 x 5 cm<br />

Two male figures one throwing [P31]<br />

printed on postcard paper<br />

7 x 5 cm<br />

Male bather pulling on anchor chain [P36]<br />

printed on postcard paper<br />

13.8 x 8.7 cm<br />

36

Two naked men facing each other on beach II [P53]<br />

printed on postcard paper (inverted)<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

Male figure in bathing shorts lying on towel [P55]<br />

printed on postcard paper<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

Portrait of Percy Farrant [P54]<br />

printed on postcard paper<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

Male figure hanging off wooden dock joist [P56]<br />

printed on postcard paper<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

37

although they were all living through what was certainly a tumultuous decade, beginning with a<br />

world-wide economic depression, the cause of steep rises in unemployment and poverty and<br />

consequent political agitation in many countries. In international politics the gradual<br />

emasculation of the power, prestige and influence of the League of Nations was seen in its<br />

repeated failure to prevent or mitigate the aggression of the rising Fascist powers, by Japan in<br />

Manchuria and China, Italy in Abysinnia, Germany in re-occupying the Rheinland, then marching<br />

into Austria, the Sudetenland and, finally, into all of Czech Bohemia and Moravia, and – what<br />

perhaps aroused the artistic community to its most vehement protest – the failure of democratic<br />

powers to take any meaningful action against Fascist and Nazi intervention in the three yearlong<br />

Spanish Civil War whose outbreak had coincided, ironically, with the Nazis’ showcase<br />

Olympic Games in Berlin.<br />

With one exception (for Schwitters’ collages) absent, too, are any reminiscences in <strong>Vaughan</strong>’s<br />

Journal of significant exhibitions of contemporary art in that decade that he might have seen,<br />

and to which, with hindsight, art historians tend to attribute undue impact. Among the many art<br />

galleries in London during the interwar years, historians often single out the likes of the<br />

Leicester, Mayor, London, Reid & Lefèvre, Zwemmer and New Burlington galleries, but in terms<br />

of impact, perhaps only the scandal aroused by the International Surrealist Exhibition at this last<br />

in 1936 might have made an impression with the broader public. Nor does <strong>Vaughan</strong> make any<br />

mention in his Journal of the ‘rising stars’ of British modernism such as Moore, Nicholson,<br />

Hepworth, Piper and painters of the more engagé Euston Road School - or even to Sutherland,<br />

whose sensibility and style <strong>Vaughan</strong> is known to have admired.<br />

Nor are the emerging new theories and interpretations that accompanied the developments in<br />

photography during those interwar mentioned in <strong>Vaughan</strong>’s journal. Only a vague recollection by<br />

his colleagues attests to his interest in foreign films – and by extension, presumably photography<br />

too – from France, Russia and Germany. In the service of propaganda for the new state, Russian<br />

artists turned photographers such as El Lissitzky and Rodchenko had incorporated innovative<br />

typography, abstract geometry, disorientating viewpoints and collage techniques. In Germany<br />

two complementary strains ran in parallel: on the one hand the documentary, unsentimental style<br />

of ‘Neue Sachlichkeit’ – in photography, termed ‘Neue Optik’ - and seen for example in August<br />

Sanders’ ambition to document the German nation in hundreds of portrait studies; and, on the<br />

other, experimentation with photographic techniques, such as in Christian Schad’s<br />

‘schadographies’, Moholy-Nagy’s ‘photograms’ and the photocollaged work of Herbert Bayer.<br />

We cannot now know with certainty which photographic exhibitions <strong>Vaughan</strong> visited, or which<br />

publications he read. Given his interest in photography, he is unlikely to have overlooked The<br />

Studio magazine’s photographic annual entitled ‘Modern Photography’ launched in 1931, which<br />

ran until 1943. Each annual’s section of more than 60 photographs was prefaced by one essay<br />

on aesthetic and stylistic developments in photography, and another on technical developments<br />

in cameras, shooting film, darkroom printing, and so on. Quaintly for us today, every detail of the<br />

camera, lens aperture and shutter speed, and paper used, were listed in the index for almost all<br />

the images. Colour photography also began to appear in the 1936–37 annual.<br />

From the very first, the focus of the ‘Modern Photography’ annual was international;<br />

contemporary French, German, Hungarian and Japanese photographers dominated, with some<br />

British and American, but only one or two unremarkable Soviet Russians. Experimental<br />

Dick with drape [PL5]<br />

photographic print on Agfa Brovira paper<br />

30.2 x 25 cm<br />

38

39

Boy fishing with a net [PL8]<br />

photographic print on Agfa Brovira paper laid on card<br />

24 x 29 cm<br />

40

House captain, portrait of John Cecil Wilmot Buxton [PL13]<br />

photographic print on Agfa Brovira paper<br />

25 x 30.2 cm<br />

41

Studio portrait (left side) of model with drawing in background [PL14]<br />

photographic print on Agfa Brovira paper<br />

25 x 30.2 cm<br />

42

photography was not overlooked: on the one hand, examples of negative and solarized prints,<br />

collage and photograms were included and discussed in the essays; on the other, fashion and<br />

advertising photography was admitted. Besides having their work reproduced in this annual,<br />

photographers such as Brandt, Man Ray and the Bauhauslers Bayer and Moholy-Nagy would<br />

also hold exhibitions in London during that decade. However, it was the contrasting fields of<br />

photojournalism and fashion photography that probably achieved the greatest impact in this<br />

period. The work of photojournalists such as Bert Hardy and fashion photographers such as<br />

Cecil Beaton (as well as several of the other known-to-be-gay photographers mentioned above)<br />

found greater resonance and public recognition during that decade.<br />

David Mellor has written that ‘in 1927 photography had been primarily a matter of studio practice,<br />

of artifice and contrivance in the interest of an ideal, usually of a portrait ideal’. 7 Indeed, the<br />

arrival of the miniature camera, Mellor suggests, ‘was the necessary technical precondition for<br />

the enormous growth in the use of this informal picture type of the 1930s’. Bert Hardy had<br />

confessed ‘when I started off with a Leica (in 1928), it changed my life completely. It started me<br />

as a photographer properly.’ 8 For the enthusiastic amateur photographer such as <strong>Vaughan</strong>, the<br />

annual ‘Modern Photography’ could offer a stimulating survey of contemporary international work,<br />

as well as technical advice and encouragement. The 1933–34 annual’s essay on technical<br />

progress endorsed <strong>Vaughan</strong>’s decision to purchase a Leica. It claimed that the arrival of the<br />

Leica III model ‘had established Leica photography as one of the outstanding technical<br />

developments in modern photography’. And for the newcomer joining Lintas as a trainee layout<br />

artist in 1931, that year’s annual had fortuitously advertised ‘A.Tolmer’s ‘Mise en Page’ (‘a super<br />

text<strong>book</strong> of advertising’) for ‘the Theory and Practice of Layout’, to be published in the autumn.<br />

And would <strong>Vaughan</strong> have missed the Royal Photographic Society’s ‘Exhibition of Modern<br />

Photographs’ in 1932, or its ‘The Modern Spirit in Photography and Advertising’ in 1934,<br />

exhibitions which included work by many of the same names as featured in the ‘Modern<br />

Photography’ annuals?<br />

In the collection of <strong>Vaughan</strong>’s photographs presented here, we see echoes of Russian montage<br />

or collage, of Surrealist spatial and perspectival contradictions, of German sports culture and<br />

sun-worship photography, and of Cartier-Bresson’s ‘ decisive moment’ permeating <strong>Vaughan</strong>’s<br />

more conventional compositional cropping and snapshot improvisations. These themes and<br />

techniques were explored in <strong>Vaughan</strong>’s two ‘livres de photographie’, the above-mentioned<br />

‘Highgate Ponds’ and his memorial to his fighter-pilot younger brother who had been shot down<br />

in 1940, ‘ Dick’s <strong>book</strong> of photographs’. The former focused on lightly clad or naked men at ease,<br />

posing or sunbathing in the heat of summer, the photographs in the album interspersed with<br />

hand-drawn inscriptions indicating the rising heat at the Ponds. The latter ‘livre’ illustrated the<br />

greater range of subjects that <strong>Vaughan</strong> tackled with his camera beyond the Pagham<br />

photographs, such as landscapes, men at work, dancers, studio portraits, and still lives.<br />

Can one speak of particular characteristics in <strong>Vaughan</strong>’s photographs? What is evident is that<br />

<strong>Vaughan</strong>, the sensitive enthusiast, was experimenting with different genres, discovering the<br />

close-up, the informal ‘decisive moment’ shot, the action shot, the panoramic landscape, an<br />

occasional still life, as well as live photography of the ballet in performance. It is probable that he<br />

had instructive exchanges of ideas with more experienced colleagues at Lintas who might have<br />

seen some, even if not all of his early efforts with his first camera. It is difficult to imagine that he<br />

did not find some inspiration from exhibitions and publications such as those mentioned above.<br />

43

Male figure on hands and knees [P57]<br />

printed on postcard paper (inverted), inscribed ‘Mud’ in ink verso<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

Wreck of fishing boat on beach [P60]<br />

printed on postcard paper (inverted)<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

Male figure in bathing shorts lying on beach [P58]<br />

printed on postcard paper (inverted)<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

Friends of the artist sitting on Pagham beach [P70]<br />

printed on postcard paper<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

44

Dick <strong>Vaughan</strong> in the distance standing beside boat [P61]<br />

printed on postcard paper<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

Two beached boats and sluice [P62]<br />

printed on postcard paper<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

Portrait of female friend on Pagham beach [P71]<br />

printed on postcard paper<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

The Quickstep [P64]<br />

printed on postcard paper<br />

8.7 x 13.8 cm<br />

45

46

At times <strong>Vaughan</strong> gives a clue as to how he sees and feels through the camera. He can be the<br />

voyeur and intruder, but he doesn’t belong among the sitters or those standing around at<br />

Highgate Ponds. Nevertheless his wandering and taking shots is tolerated. He is a ‘spy’<br />

capturing moments that others – his subjects – are unaware of or even might not dream of<br />

seeing preserved for posterity. Prunella Clough reminisced to Gerard Hastings: ‘Keith used the<br />

camera almost as a justification to look – really look – at the male nude. Staring at an unclothed<br />

person, outside the life class, is an intrusive activity and makes people uncomfortable … when<br />

Keith had a camera fixed to his eye, it legitimized his gazing at another unclothed human being.’ 9<br />

With one exception [PC5] Four figures on a beach, <strong>Vaughan</strong>’s collages [PC1-7, ILL. P.21-27], are inspired<br />

by the setting of the mostly empty beach, where sand and undefined blue sky or water blend<br />

without boundaries or horizons. The idea of the empty foreground expanse with scattered<br />

‘incidents’ may owe something to contemporary Surrealism, in the work of Salvador Dalí, Yves<br />

Tanguy, or perhaps Henry Moore’s 1930’s studies for sculpture. However, the introduction of a<br />

cut-out photograph of a figure suggests a homage to, or tryout for, other sources of inspiration:<br />

von Gloeden’s Figure on a pedestal with [PC4] Male figure seated on wooden breakwater, the<br />

angled propaganda image of sunny New Soviet Man for [PC2] Smiling man with hands on head,<br />

and Herbert Bayer’s Figure on a beach for [PC3] Figure lying on beach at night. In contrast, the<br />

floating figures in [PC1] Two male figures on a beach are of a different order, and seem to<br />

presage an encounter or exchange, with a frisson of sexual tension in a misty, unboundaried<br />

ether. The occasional sketched-in boats may refer to sights at Pagham, without yet situating the<br />

setting with precision. Such outlines of boats would occasionally reappear in his later drawings<br />

with figures. By contrast, the metal buoy [PC5 VERSO] is a classic Surrealist objet trouvé: a banal,<br />

inert, accidental find that is transformed by its foregrounding into a menacing living form<br />

threatening to explode out of the frame.<br />

The 1920s saw a new daring with close-up portraiture that asked for the sitter to submit to the<br />

intimacy of very close observation. This intimacy might capture an angle, a mood, or an expression<br />

without needing to portray the full compass of the head. The technical capabilities of the camera<br />

lens made these close-ups possible. <strong>Vaughan</strong> must have thought that the full-size black-andwhite<br />

prints (measuring roughly 30 x 25 cm) in this exhibition worth producing, possibly to show<br />

or give to his sitters, or indeed for himself to learn from or enjoy. With the exception of the couple<br />

of rock studies and beach scenes, all are portrait or figure studies, in the studio or outdoors,<br />

ranging from youths to young men, with only one formal, beaming, bespectacled mature figure,<br />

resembling a study for a worthy’s head-and-shoulders memorial sculpture. Noteworthy are the<br />

two solarized studies of his brother Dick [PL1], [PL5], which appear posed rather than spontaneous.<br />

In the same vein, <strong>Vaughan</strong> chose to pose a model as Michelangelo’s David [PL2], another as the<br />

Apollo Belvedere (with hessian sheet!) [PL9], and to lay out the Man with oil drum [PL3], in imitation<br />

of an artistically enticing female nude in the most flattering flagrancy.<br />

Bather throwing ball [PL11]<br />

photographic print laid on Agfa Brovira<br />

paper, inscribed ‘5/-’ in ink verso<br />

30.2 x 25. cm<br />

In the Pagham photographs <strong>Vaughan</strong> also adopts the role of the nostalgic pictorialist. A young<br />

man is captured in the distance, amidst the picturesque decay of the boatyard. <strong>Vaughan</strong><br />

described the evocative setting of ‘the hulks of boats with their tarred backs and the sun<br />

bleaching and rotting the paintwork, rearing their mass against the china sky’ 10 where he<br />

spotted Stan’s younger brother Len ‘moving slowly, rather disinterestedly, the mud over his<br />

ankles and the large black flanks of timber dwarfing him’. 11 This group of boatyard photographs<br />

are an exception among the others taken at Pagham. The greatest number record the ‘pagan’<br />

47

pleasures of sun-worship, uninhibited nudity, and young men at rest or play on the isolated<br />

beach. In this <strong>Vaughan</strong> appears as the vicarious (homosexual) hedonist: achieving pleasure and<br />

release by exploring and capturing the lithe naked bodies through his viewfinder.<br />

Peter Adam explained to Gerard Hastings: ‘Photography allowed Keith to evolve a close and<br />

intimate relationship with the model’s body in such a way that he, being a somewhat diffident<br />

and reserved character, would have found difficult to do otherwise. Taking a photograph for<br />

Keith was a way of ‘making love’ to the bodies he admired’. 12 Indeed it had been at Highgate<br />

Ponds in the early 1930s that <strong>Vaughan</strong> first saw Stan doing handstands, and he would<br />

eventually take Stan and his brother Len to Pagham, while Harold Colebrook brought his friends<br />

Max and Chris, all of whom appear in the photographs. Of Stan at Pagham, <strong>Vaughan</strong> wrote: ‘A<br />

silent, objectively physical relationship grew between us … the greater part of the time I saw him<br />

he was naked: the real point of contact was between his body and my eyes. Detached and<br />

dispassionate.’ 13 And of Len, <strong>Vaughan</strong> would later reminisce: ‘I could only touch his body<br />

through the lens of my camera … he liked to know the importance of his body and sunbathed<br />

for this reason … Len stripped and moved about with his copper-varnished limbs, I followed with<br />

my camera obsessed with the colour and the intangible beauty of the scene.’ 14<br />

At this stage of indecision about his future direction, <strong>Vaughan</strong>’s photographic sensibility seems<br />

at best mildly experimental, with reflections of Surrealism, albeit tempered by a certain British<br />

reserve. Nothing is outright shocking. There are no photographs of repellent decomposition à la<br />

Dalí or Buñuel, no aggressive photo-propaganda à la John Heartfield, no startling disparities à la<br />

Dora Maar. In the ‘Highgate Ponds’ album, however, he does toy with contradictions of spatial<br />

location, of perspectival positioning, and use unnatural repetition frozen in a framework of<br />

geometry. With one exception – that of solarization – there is no technical wizardry à la Moholy-<br />

Nagy, artifice à la Beaton, or distortion and darkroom manipulation à la Brandt. In the interwar<br />

period readings about class and status were still visible and topical in portraiture as a genre, as<br />

seen for example in the contrasts between the high society subjects of Beaton and the workingclass<br />

subjects of Brandt. <strong>Vaughan</strong>, by contrast, uses the naked figure as his central subject in<br />

settings almost entirely devoid of specific details, so that such readings are not to be found in<br />

this collection of his photographs.<br />

In his Journal, reminiscing on the previous summer in the bleak January of 1940, <strong>Vaughan</strong><br />

wrote: ‘It is difficult to recall those days of last summer; difficult to believe that they ever existed,<br />

waking each morning with the sun already hot and high in the sky. Walking out through the<br />

shallows of the sinking tide and wandering all day over the islands of shingles with nothing but<br />

the white flecks of birds and our naked bodies browning in the sun and salt. … Impossible to<br />

believe that war was anything more than a figment in the imagination of politicians. Yet it must<br />

have been some premonition that made me spend so much of each day with my eye screwed to<br />

the view-finder of a Leica in a desperate effort to preserve something one was afraid was<br />

vanishing forever.’ 15 At last, after the six years’ intermission of war mostly spent serving in the<br />

Pioneer Corps in Britain, <strong>Vaughan</strong> ‘reawoke’ on VE day and recorded one of the lengthiest and<br />

most poetic entries on a single day in his Journal : ‘Today I went to the river and the sun. … I sat<br />

under the shelter of the small earth cliff and took off my clothes. There was no-one about and<br />

the sun was a steady stream of heat. … I lay back and stretched myself into the brilliant warmth.<br />

Years have passed since I last did this. Perhaps I am the last person in Europe who can still lie in<br />

the sun. … A deep sensual contentment descended over me … ’ 16<br />

48

NOTES<br />

1 Emmanuel Cooper, Fully exposed: the male nude in photography, London 1990, p. 92.<br />

2 As seen in the October 1927 issue of ‘Drawing & Design’, from the publishers of ‘The Studio’, ‘Commercial Art’ and<br />

other ‘Special Publications dealing with many phases of Art’ [sic].<br />

3 The infamous ‘Paragraph 175’ of the Reich’s Criminal Code, the repeal of which, although voted for in 1929, was<br />

never implemented until it was ‘eased’ in 1969.<br />

4 Cooper, ibid., pp.73–74.<br />

5 David Mellor, in The Real Thing, London 1975, p. 27.<br />

6 Photography was regularly featured in AMG, but the issues of March 1930, August 1931 and August 1932 had<br />

specially dedicated sections. An online database for all the AMG issues has been assembled at RIT (The Rochester<br />

Institute of Technology, USA: Rochester also being the original home of Eastman Kodak).<br />

7 Mellor, op.cit., p. 25<br />

8 Mellor, ibid., p. 25.<br />

9 Gerard Hastings, Keith <strong>Vaughan</strong>: the photographs, Pagham Press 2013, p. 13.<br />

10 Colin Cruise, Keith <strong>Vaughan</strong>, Figure and Ground, Bristol 2013, p. 23.<br />

11 Cruise, ibid., p. 23.<br />

12 Hastings, op. cit., p. 14.<br />

13 Quoted by Hastings, ibid., p. 6, from <strong>Vaughan</strong>’s unpublished ‘Memoire’, February 1965.<br />

14 Hastings, ibid., p. 74.<br />

15 <strong>Vaughan</strong>, Journal & drawings, edited and published by Alan Ross, 1966, p. 14.<br />

16 <strong>Vaughan</strong>, ibid., p.103.<br />

Studio portrait IV [PL17 VERSO]<br />

photographic print laid on card<br />

20 x 16.6 cm (image); 30.2 x 25.5 cm (card)<br />

49

50

Sources and further reading<br />

Arts et Métiers Graphiques, Photographie, Paris 1930 (reprinted by Paul Attinger, Neuchatel<br />

1980)<br />

Pierre Borhan, Men for Men: homoeroticism and male homosexuality in the history of photography<br />

since 1840, London 2007<br />

Cristian Bouqueret, Des années folles aux années noires: la nouvelle vision photographique en<br />

France 1920–1940, Paris 1997<br />

Emmanuel Cooper, Fully exposed: the male nude in photography, London 1995<br />

Colin Cruise (ed.), Keith <strong>Vaughan</strong>, Figure and ground: drawings, prints and photographs,<br />

Bristol 2013<br />

William A. Ewing, The Body: photoworks of the human form, London 1994<br />

James Gardiner, Who’s a pretty boy then? 150 years of gay life in pictures, London 1996<br />

Gerard Hastings, Keith <strong>Vaughan</strong>: the photographs, Pagham Press, 2013<br />

Gerard Hastings, Awkward artefacts: the ‘erotic fantasies’ of Keith <strong>Vaughan</strong>, Pagham Press, 2017<br />

Tobias Natter and Elisabeth Leopold, Nude Men: from 1800 to the present day, Leopold Museum<br />

Vienna, 2012<br />

Max Scheler and Matthias Harder, Herbert List: the monograph, Munich 2000<br />

Len Sharpe, The Lintas Story: impressions and recollections, London 1964<br />

Philip Vann and Gerard Hastings, Keith <strong>Vaughan</strong>, London 2012<br />

Keith <strong>Vaughan</strong>, Journal & drawings, edited and published by Alan Ross, 1966<br />

Bruce Weber and James Crump, George Platt Lynes: photographs from the Kinsey Institute,<br />

Boston Mass., 1993<br />

Malcolm Yorke, Keith <strong>Vaughan</strong>: his life and work, London, 1990<br />

The Real Thing: an anthology of British Photography 1840–1950, Arts Council of Great Britain,<br />

1975<br />

Thirties: British art and design before the war, Arts Council of Great Britain and Victoria & Albert<br />

Museum, 1979–80<br />

Ashley Havinden: advertising and the artist, National Galleries of Scotland 2003<br />

Deckchair [PL4]<br />

photographic print on Agfa Brovira paper<br />

30.2 x 25 cm (card)<br />

51

Tracey ‘Bunnie’ Stamp, pictured centre, 1952<br />

Austin/Desmond Fine Art would like to acknowledge the following for help and assistance<br />

rendered in the production of this exhibition and catalogue:<br />

The Stamp Family and the late Tracey 'Bunnie' Stamp<br />

Mr Philip Wright<br />

Mr Colin Mills<br />

Mr Fred Mann<br />

Lorraine Finch ACR at LF Conservation and Preservation<br />

Kim Driscoll at Archer Architects<br />

Catalogue design by Peter Gladwin at Artquarters Press<br />

Printing by Artquarters Press<br />

Envision and curation by David Archer<br />

ISBN 978-1-872926-38-4<br />

Front cover:<br />

Boy in fishing net (detail) [P3]<br />

Back cover:<br />

The original hand-painted cardboard box which contained the postcard sized Pagham Beach photographs<br />

52

Austin / Desmond Fine Art