You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

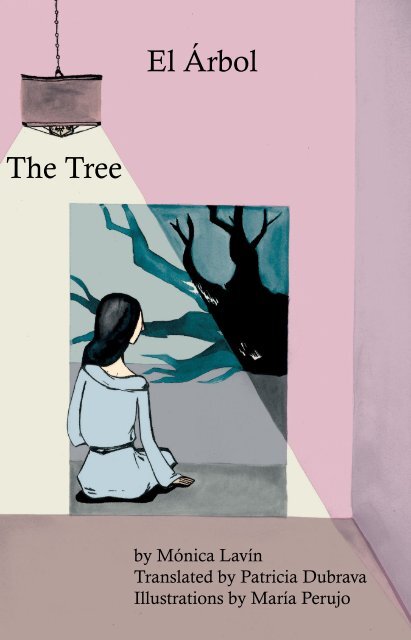

<strong>El</strong> Árbol<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Tree</strong><br />

by Mónica Lavín<br />

Translated by Patricia Dubrava<br />

Illustrations by María Perujo

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF | LynleyShimat Lys<br />

CO-EDITOR | Sáshily Kling<br />

CO-EDITOR | Tina Togafau<br />

CO-EDITOR | Marley Aiu<br />

CO-EDITOR | Jimi Coloma<br />

CHAPBOOK EDITOR | LynleyShimat Lys<br />

ADMINISTRATIVE & TECHNICAL SUPPORT<br />

University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Student Media Board<br />

Mahalo nui loa to Sandy Matsui for guidance!<br />

Hawaiʻi Review logo by Bryce Watanabe<br />

Hawaiʻi Review is a publication of the Student Media Board<br />

of the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. A bold, student-run<br />

journal, H\R reflects the views of its editors and contributors,<br />

who are solely responsible for its content. Hawaiʻi Review<br />

is a member of the Coordinating Council of Literary<br />

Magazines and is indexed by the Humanities International<br />

Index, the Index of American Periodical Verse, Writer’s<br />

Market, and Poet’s Market.<br />

CONTACT: hawaiireview@gmail.com<br />

SUBMIT: hawaiireview.org<br />

Copyright 2018 by Board of Publications<br />

University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa.<br />

ISSN: 0093-9625

<strong>El</strong> Árbol | <strong>The</strong> <strong>Tree</strong><br />

Table of Contents<br />

<strong>The</strong> <strong>Tree</strong> | 5<br />

<strong>El</strong> Árbol | 17<br />

––––<br />

Author’s Note | 26<br />

Translator’s Note | 29

As it happens, sleep is interrupted in<br />

various ways. Sometimes by dreams, sometimes<br />

by noises that penetrate consciousness enough to<br />

open our eyelids. Lola woke because she thought<br />

she heard something unusual. Finding herself<br />

sitting up in bed, she stayed still, as if the rustle<br />

of her own movements would overshadow the<br />

sound that had startled her awake. She stared<br />

attentively into the darkness of the room, but<br />

the noise didn’t repeat. Looking at her husband’s<br />

head on the pillow, she envied his soft, deep-sleep<br />

breathing. Lola did not want to share this oddity<br />

with him.<br />

It was impossible to go back to sleep<br />

without seeking some explanation, so she got up.<br />

Groping in the darkness until she felt the plush<br />

texture of her robe, she put it on and went quietly<br />

to the children’s room. She only hovered at the<br />

doorway. It had happened before, especially when<br />

they had a fever or the flu, that a sudden fear<br />

woke her and she went to check on them, to peer<br />

into their little faces and cup her hand over their<br />

noses to feel the exhalation of their breath. <strong>The</strong>y<br />

were alive. Now she went down the hall barefoot<br />

and scanned the living and dining rooms. <strong>The</strong><br />

bare windows allowed the light of night to enter<br />

unobstructed; even so she flipped the switch to<br />

verify that things were in their place and there<br />

were no unexpected shadows. She’d always been<br />

afraid to turn on or shut off lights, because then<br />

7

the intruder—if there were one—would know<br />

that someone had become aware of him. But<br />

this time she looked calmly at the large armchair,<br />

the smaller one, the bookshelf in the back, the<br />

table and chairs, the china cabinet. All quiet. Her<br />

breathing began to slow down. And no further<br />

sound confirmed that what she’d heard while she<br />

slept had even happened. Could a connection<br />

in the brain make noise, a snap of chemical<br />

transmitters be heard? What happened with those<br />

surprised by a blood clot that abruptly altered<br />

their faculties? Did they hear something moments<br />

before the fatal event?<br />

Confirming that the rooms were in<br />

order gave her pleasure. It was like spying<br />

unannounced on her own home to prove she<br />

was capable of maintaining a certain state of<br />

things. For example, that they’d been able to<br />

pay the rent for a comfortable place, especially<br />

with the quantity of windows that opened on<br />

others’ gardens, giving the illusion of possessing<br />

them; that they’d furnished and decorated it and,<br />

moreover, kept it clean and neat. <strong>The</strong> kitchen<br />

faced the street. She went into it thinking the<br />

casserole could have slipped off the drain basket<br />

at the sink. Sometimes she piled dishes without<br />

putting them away. Especially at night, when she<br />

wanted to watch a movie with her husband, when<br />

the children had already been lulled to sleep<br />

with a story and she had covered them and shut<br />

8

off the light that she kept lit until then, because<br />

the oldest asked for it. <strong>The</strong> kitchen was in order<br />

and all was so quiet that it seemed as if she were<br />

alone in the house; only the profusion of glasses<br />

in the drain basket gave evidence that she lived<br />

with her family. And strangely, that sudden,<br />

disturbed waking, the resultant inspection of the<br />

rooms in silence, allowed that slice of the night<br />

to belong to her. One inhabited nights by offering<br />

sleep as a gift to darkness. But this night was hers,<br />

like when she was a teenager and the excitement<br />

of the day just concluded made her find her<br />

notebook in the chest of drawers and review the<br />

look of the boy she liked and what he had said<br />

(which she already couldn’t remember and even<br />

less write with exactness). She approximated and<br />

exaggerated the scene, but it was satisfying to<br />

replay it and feel again the hand that took hers<br />

in the movie theatre. Sleep was a hindrance that<br />

made her forget the warm and naughty sensation<br />

of complicity. She also remembered a time when<br />

she was leaving home for several months and<br />

spent the night before departure in the living<br />

room, thinking about her home, her parents,<br />

her siblings, her city. She was saying goodbye.<br />

Or how when suddenly in the night she brushed<br />

against her husband’s body and his smoothness<br />

and smell, his solidity, woke her desire to violate<br />

that, to demand an answer to her midnight<br />

appetite. Exceptions.<br />

9

This night seemed to have a border, a dark<br />

edge separating it from the light that announced<br />

night’s passing each morning. She heard a car<br />

squealing to a stop. <strong>The</strong> sound returned her<br />

to her task. It was difficult to see through the<br />

kitchen window because the sink was in the<br />

way. She went to the bathroom to look out to<br />

the street, shut off the light she’d turned on in<br />

order to see better what had happened outside.<br />

<strong>The</strong> night seemed unusually dark, except for the<br />

red taillights of the car that blinked in front of<br />

her house like an animal in danger. She went<br />

downstairs and opened the door to the wrought<br />

iron enclosed carport. She saw the car reverse,<br />

turn to go back the way it came and disappear.<br />

<strong>The</strong> streetlight was out. Again alone with the<br />

night, she now knew there was a connection<br />

between the braking car and the noise that<br />

had awakened her. Because the street seemed<br />

impenetrable, she looked then toward the carport<br />

and discovered a dark mass behind her car, as<br />

if the night had stained it with ink. She eased<br />

her way around the car, couldn’t see the cement<br />

floor, but discerned an additional blackness, an<br />

uncomfortable presence. Once close enough,<br />

she was astonished to see the leafy branch of<br />

a tree thrust through the bars of the grille and<br />

lying inside the carport. She touched a branch,<br />

ran her gaze over that giant jumble of branches<br />

straining between the bars, as if the tree were<br />

10

egging. Walking with care toward the latticed<br />

wall, avoiding branches, she felt the cold of the<br />

cement through the soles of her feet. Finally she<br />

understood. <strong>The</strong> main trunk of the tree blocked<br />

the street. It had fallen from the front sidewalk<br />

and sliced through the bars to its full length,<br />

landing nearly across the carport. A bit taller and<br />

it would have crashed into the house’s windows.<br />

Lola made out the wires on the sidewalk behind<br />

the carport; the tree had taken out the streetlight<br />

and twisted the pole to the right. <strong>The</strong>n she felt<br />

afraid of that live electricity running near her<br />

feet, from which there could be a spark to catch<br />

the tree on fire. Like many in the city, it was an<br />

ash and her street was full of trees, being an old<br />

neighborhood, but nobody thought that one of<br />

them would collapse in the middle of the night—<br />

fortunately, because it could have crushed cars,<br />

people, her and her children leaving the house.<br />

She retreated from the metal bars and took shelter<br />

under the eaves of the house, close to the top<br />

of the highest branches that now lay at her feet.<br />

She should go wake her husband, so he could<br />

see what had happened, a tree spread across the<br />

carport, a tree lying across the street. She also<br />

ought to call the police or fire department—who<br />

do you call in such a case? Not only were the<br />

wires a danger, but a car could collide with that<br />

unexpected trunk on the darkened street. But she<br />

didn’t do any of it, sat on the curb that bordered<br />

11

the garage and stayed silent. <strong>The</strong> night and that<br />

fallen tree still belonged to her. <strong>The</strong> tree was<br />

at her feet; she contemplated its destiny with<br />

sadness. She’d been invited to the mourning. And<br />

she appreciated that there weren’t condolences or<br />

volunteers who wanted to cut it into pieces, divert<br />

the traffic, extract each of the branches embedded<br />

in the metal. At least not yet. Like when Olga<br />

Knipper, Chekhov’s wife, wanted to spent the<br />

night with her dead husband in Badenweiler<br />

before telling anyone else. Lola read that in a<br />

magazine in her gynecologist’s waiting room.<br />

It was a story by a certain Raymond Carver.<br />

Although it treated Chekhov’s death, it was about<br />

the suffering of the actress he’d married four<br />

years before and about the waiter who that night<br />

had brought them three glasses of champagne. It<br />

was about the unexpected and grief. Like Olga<br />

Knipper, she wanted to spend time alone with the<br />

fallen tree that wasn’t even hers, or perhaps was<br />

hers because she saw it from the kitchen window<br />

daily although she ignored it; it was just there,<br />

stable and firm. Like the house where she lived<br />

as a girl or her father’s office where she went to<br />

visit him so often; like her parents’ marriage,<br />

fixed as a scene in a film that one day rips. She<br />

thought of the days when she opened the door<br />

to enter the house after school and the world was<br />

that house with its garden, immovable, rooted<br />

like a mountain. And the set table awaited them<br />

12

to hear the stories of their mornings between the<br />

clatter of cutlery and tortilla-wrapped meatballs.<br />

It was absurd to be thinking of meatballs and<br />

the cook who had fallen ill when she stopped<br />

working for them. That story of the solitary<br />

grieving of Knipper with the dead writer in the<br />

room, close and still warm, was different from<br />

Carver’s other stories, as she discovered when<br />

she found his books. Although not completely,<br />

because the writer knew how to put the accent<br />

on silence. And she enjoyed reading him for that.<br />

It seemed as if nothing happened between the<br />

Morgan and Myers and Webster and Stone, and<br />

what happened was exposure, fragility, solitude.<br />

This fallen tree had arrived to upset the course<br />

of the night, to caress her legs with the tender<br />

leaves of its crown. She thought of her sleeping<br />

children and how, when she read that story about<br />

the death of Chekhov they did not exist nor<br />

were even a possibility. She had just met the one<br />

who would be their father and still didn’t have to<br />

organize a domestic world. She ran her eyes over<br />

the dark branches and made out a shape, thought<br />

with horror of a rat. But rats don’t climb into<br />

trees; besides it was a still shape. A dead bird?<br />

Not long ago she had seen one under the terrace<br />

window; it seemed to have been dashed against<br />

the glass, killed by the illusion of transparency.<br />

It wasn’t just any death. She picked it up in a<br />

newspaper because she didn’t want to feel its<br />

13

temperature, to know if it was recent or cold from<br />

the hours since it had died. She leaned over the<br />

branch and made out the nest. If she had been<br />

someone who worried about animals and didn’t<br />

go around thinking to possess the night for a<br />

time, she might have taken the nest of twigs and<br />

carried it to the terrace so the little eggs it surely<br />

held would survive if the mother found them<br />

before the squirrels did. Staring fixedly, she tried<br />

to decipher the contents of the nest. She felt the<br />

wind of dawn rising and the first clarity start to<br />

lift the curtain of night.<br />

It was time to go back inside. She heard<br />

a patrol car; someone had done the right thing<br />

and called. Looking for the last time at the bulk<br />

of the uprooted tree, she imagined the increased<br />

light its absence would create in the kitchen<br />

window. That would be all that remained of that<br />

ash: a gap as memory of its shade. She closed<br />

the door behind her, and before getting back in<br />

bed next to her husband’s placid sleep, went into<br />

the children’s room and cupped her palm to feel<br />

the vapor of their breath. Calmed, she went to<br />

her bedroom. Tomorrow they would find out<br />

what happened. She would pretend surprise. She<br />

wouldn’t tell them that she was there, seated in<br />

the silence of the night, attending the wake. She<br />

would not mention that the night had been hers.<br />

14

15

16

<strong>El</strong> árbol<br />

Ocurre que el sueño se interrumpe por diferentes<br />

razones. Algunas provienen del pensamiento,<br />

otras de los ruidos que traspasan nuestros<br />

párpados. Ambas son inciertas y difusas.<br />

Lola se despertó porque creyó advertir un<br />

ruido inesperado. Se sentó en la cama y se<br />

quedó muda, como si el sonido de sus propios<br />

movimientos fuese a opacar aquella señal que la<br />

sobresaltó. Permaneció con la mirada atenta en<br />

la oscuridad de la habitación, pero el ruido no se<br />

repitió. Miró a su marido sobre la almohada, le<br />

envidió la respiración dulce del sueño profundo.<br />

No quiso compartirle esa extrañeza.<br />

Se puso de pie porque resultaba imposible<br />

vencerse sobre el colchón sin explicación alguna.<br />

Tanteó en la oscuridad hasta reconocer la textura<br />

felpuda de su bata. Se la ató al cuerpo y siguió<br />

despacio al cuarto de los niños. Asomó tan sólo<br />

por el quicio de la puerta. Ya le había sucedido<br />

que algún temor inesperado, sobre todo cuando<br />

tenían fiebre o estaban mal del estómago, la<br />

llevaba a espiarlos de noche, a acercarse a sus<br />

pequeños rostros y colocar su mano sobre la<br />

nariz para sentir el alivio de su respiración.<br />

Estaban vivos. Siguió por el pasillo descalza<br />

y oteó la sala y el comedor a la derecha. La<br />

ausencia de cortinas permitía que la luz de la<br />

noche entrara rotunda; aun así dio al apagador<br />

17

para verificar que las cosas estuvieran en su lugar<br />

y que no hubiera sombras inesperadas. Siempre<br />

que tenía miedo prendía y apagaba la luz para<br />

que el intruso —si acaso lo hubiera— supiera<br />

que alguien había advertido sus intenciones.<br />

Pero ahora miraba sin miedo el sillón largo, el<br />

más corto, los libros al fondo, la mesa rodeada<br />

de sillas a la entrada, el trastero. Todo quieto.<br />

Su propia respiración comenzaba a aquietarse.<br />

Y ningún ruido confirmaba que lo que hubiera<br />

escuchado antes mientras dormía fuera cierto.<br />

¿Sería posible que una conexión del cerebro<br />

hiciera ruido, que un chasquido de los<br />

transmisores químicos se pudiera escuchar? ¿Qué<br />

pasaba con quienes eran sorprendidos por un<br />

tapón de sangre que cambiaba bruscamente sus<br />

facultades? ¿Escuchaban algo momentos antes de<br />

la fatalidad?<br />

Confirmar que la sala estaba en orden le<br />

dio gusto. Era como espiar su casa a deshoras<br />

para comprobar que era capaz de mantener<br />

cierto estado de las cosas, que habían podido<br />

pagar la renta de un lugar grato (sobre todo<br />

por la cantidad de ventanas que se abrían a los<br />

jardines de las otras casas dándoles la ilusión de<br />

poseerlos); amueblarlo y vestirlo de los objetos<br />

de uno y otro, y encima que estuviera limpio y<br />

recogido. Entró a la cocina que daba a la calle<br />

pensando que una cacerola podía haber resbalado<br />

del escurridor al fregadero; a veces las apilaba sin<br />

18

guardarlas. Sobre todo por las noches, cuando<br />

quería ver una película en la televisión con su<br />

marido, cuando los niños ya habían sido<br />

arrullados con un cuento y los había arropado y<br />

apagado la luz que mantenía encendida, porque<br />

así lo pedía el mayor. La cocina estaba en orden<br />

y todo tan quieto que parecía que ella habitara<br />

sola esa casa; nada más la abundancia de vasos<br />

escurriendo permitía saber que ella vivía<br />

acompañada por su familia. Y extrañamente ese<br />

despertar súbito e inquieto, conforme recorría la<br />

casa en el silencio, permitía que esa hora de la<br />

casa, esa tajada de la noche, le perteneciera. Uno<br />

habitaba las noches brindando el sueño como<br />

ofrenda a la oscuridad. Pero esta noche era suya,<br />

como cuando de adolescente la excitación del día<br />

transcurrido la hacía buscar su libreta en el buró<br />

y repasar la mirada del chico que le gustaba, y lo<br />

que le había dicho (que ya no lo podía recordar<br />

y menos escribir con exactitud). Describía la<br />

escena y la exageraba, pero le satisfacía transitar<br />

por ella de nuevo y sentir la mano que atrapaba<br />

la suya en el cine. <strong>El</strong> sueño era un estorbo porque<br />

hacía olvidar la sensación cálida y traviesa de la<br />

complicidad. También recordó cuando se fue por<br />

varios meses de su casa y pasó la noche anterior<br />

a la partida en la sala, pensando en su casa, en<br />

sus padres, en sus hermanos, en la ciudad. Se<br />

despedía. O como cuando de pronto en la noche<br />

se topaba con el cuerpo de su marido y su tersura<br />

19

y su olor, y su consistencia despertaba su deseo<br />

de violentarlo, de exigir la respuesta a su apetito<br />

de medianoche. Excepciones. La noche de hoy<br />

parecía tener un borde, una frontera distinta a<br />

la de la luz del sol que anunciaba su en cada<br />

mañana. Escuchó un auto frenar con fuerza. Y el<br />

sonido la devolvió a su tarea. Era difícil mirar<br />

por la cocina porque el fregadero estorbaba. Se<br />

dirigió al baño para ver hacia la calle. Apagó la<br />

luz que había encendido para poder distinguir<br />

mejor lo que sucedía afuera. La noche le pareció<br />

inusualmente oscura, salvo por las luces rojas<br />

del auto que parpadeaban frente a su casa como<br />

animal en peligro. Echó a andar escaleras abajo y<br />

abrió la puerta que daba al garaje enrejado.<br />

Distinguió al auto que se echaba en reversa,<br />

maniobraba para tomar calle arriba y se alejaba.<br />

No había luz en el poste. Volvía a estar con la<br />

noche y ahora sabía que había una conexión<br />

entre el frenar del auto y el ruido que la había<br />

despertado. Miró entonces hacia el garaje porque<br />

la calle le parecía impenetrable, y descubrió al<br />

lado del auto allí estacionado una masa oscura.<br />

Como si se hubiera manchado de tinta la noche.<br />

Caminó esquivando su coche en el garaje. No<br />

distinguía el cemento del piso, sólo una negrura<br />

adicional, una presencia incómoda. Ya de<br />

cerca se asombró al ver la fronda de un árbol<br />

incrustada entre los barrotes de la reja y acostada<br />

en la mitad del garaje. Extendió la mano y tocó<br />

20

una rama. Recorrió a aquel gigante desvencijado<br />

con la vista, las ramas colándose entre los<br />

barrotes, como si el árbol fuese un hombre<br />

suplicante. Sintió el frío del cemento en sus<br />

plantas mientras caminaba con cuidado hacia<br />

la reja, evadiendo ramas. Por en lo entendió. <strong>El</strong><br />

fuste del árbol atravesaba la avenida. Había caído<br />

desde la acera de enfrente y se había introducido<br />

entre los barrotes de la reja para extender su<br />

largura, que topaba justa con el fondo del garaje.<br />

Si no, se hubiera incrustado en las ventanas de<br />

la casa. Lola distinguió los cables en la acera<br />

tras la reja; el árbol había vencido el alumbrado<br />

y enchuecado el poste de la derecha. Entonces<br />

sintió temor de esa electricidad viva corriendo<br />

muy cerca de sus pies, de que hubiera una chispa<br />

y el fresno se incendiara. Recordó que era un<br />

fresno como había muchos en la ciudad y que<br />

la calle donde vivía era muy arbolada por ser un<br />

barrio antiguo, y nadie pensaba que en medio de<br />

la noche (afortunadamente, porque habría podido<br />

aplastar autos, gente, a ella misma y a sus hijas<br />

saliendo de casa) se desplomara uno de ellos.<br />

Se retiró de la reja y se colocó bajo el alero de<br />

la casa, muy cerca del final de las ramas más<br />

altas que ahora yacían a sus pies. Debía entrar<br />

y despertar a su marido, que viera lo que había<br />

ocurrido, un árbol tendido en el garaje, un árbol<br />

atravesando la calle. También debía llamar a<br />

la policía, o a los bomberos, ¿a quién se llamaba<br />

21

en ese caso? No sólo los cables eran un peligro<br />

sino que cualquier coche en la noche podía<br />

estrellarse contra ese tronco inesperado. Pero no<br />

lo hizo, se sentó en la banqueta que bordeaba el<br />

garaje y se quedó en silencio. La noche todavía le<br />

pertenecía y ese árbol vencido también. Lo tenía<br />

a sus pies; contempló con tristeza su destino.<br />

Había sido invitada al duelo. Y apreció que no<br />

hubiera pésames ni voluntades que quisieran<br />

cortarlo en pedazos, menearlo con una grúa,<br />

desviar el tráfico, extraer cada una de las ramas<br />

embutidas en el metal. Por lo menos todavía no.<br />

Como cuando Olga Knipper, la mujer de Chéjov,<br />

quiso pasar la noche con su marido muerto en<br />

Badenweiler antes de avisar a los otros. Leyó<br />

aquel pasaje en una revista en el consultorio del<br />

ginecólogo. Era un cuento de un tal Raymond<br />

Carver. Aunque trataba de la muerte de Chéjov,<br />

era sobre el duelo de la actriz con quien se casó<br />

cuatro años antes y sobre el camarero que en la<br />

noche les llevó las tres copas de champaña. Era<br />

sobre lo inesperado y el duelo. Y aquí estaba<br />

ella como Olga Knipper con deseos de pasar un<br />

tiempo a solas con el árbol caído, que no era<br />

suyo ni nada, o que tal vez era suyo porque lo<br />

veía desde la ventana de la cocina todos los días<br />

aunque lo ignorara; era como esas cosas que<br />

están allí gratuitas, estables y firmes. Como la<br />

casa donde vivió de niña o la oficina de su padre<br />

a donde iba a visitarlo tan a menudo, como el<br />

22

matrimonio de sus padres, todo fijo como una<br />

escenografía que un día se rasga. Pensó en los<br />

días en que se abría la puerta para entrar a casa<br />

después de la escuela y el mundo era esa casa con<br />

jardín, inamovible, sólida como una montaña. Y<br />

la mesa puesta los esperaba a todos para escuchar<br />

el relato de sus mañanas entre el movimiento<br />

de cubiertos y las tortillas que envolvían las<br />

albóndigas. Le pareció absurdo estar pensando<br />

en albóndigas y en la cocinera que se había<br />

enfermado cuando dejó de trabajar con ellos.<br />

Aunque aquel cuento del duelo solitario de la<br />

Knipper con el escritor muerto en la habitación,<br />

cercano y todavía tibio, era distinto a los otros<br />

de Carver, como lo comprobó cuando buscó sus<br />

libros. Aunque no del todo porque el escritor<br />

sabía poner el acento en el silencio. Y ella<br />

disfrutaba leerlo por eso. Parecía que no pasaba<br />

nada entre los Morgan y Myers y Webster<br />

y Stone, y lo que pasaba era el descobijo, la<br />

fragilidad, la soledad. Este árbol caído venía a<br />

trastornarle el curso a la noche para acariciarle<br />

las piernas con las hojas tiernas de la fronda<br />

alta. Y pensó en los niños que dormían y que<br />

cuando leía aquel cuento sobre la muerte de<br />

Chéjov aún no eran un hecho o una posibilidad.<br />

Apenas había conocido a quien sería su padre<br />

y todavía no tenía que ordenar un mundo<br />

doméstico. Dejó los ojos entre el ramaje oscuro<br />

y descubrió un bulto; pensó con horror en una<br />

23

ata. Pero las ratas no andan en los árboles;<br />

además era un bulto quieto. ¿Un pájaro muerto?<br />

Se había topado hacía poco con el cuerpo<br />

de uno bajo la ventana de la terraza; parecía<br />

haberse estrellado contra el vidrio y muerto en el<br />

engaño de esa transparencia. No era cualquier<br />

muerte. Lo recogió con un periódico porque<br />

no quería sentir su temperatura, ni saber si era<br />

una muerte reciente o estaba helado por las<br />

horas transcurridas. Se inclinó hacia la rama y<br />

distinguió el nido. De haber sido alguien que se<br />

preocupara por los animales y que no anduviese<br />

pensando en poseer la noche por un rato, hubiera<br />

tomado el nido de varas y lo hubiera llevado a la<br />

terraza de su casa para que los huevecillos, que<br />

seguramente tenía, prosperaran si la madre los<br />

encontraba antes que las ardillas. Se quedó<br />

mirando fijamente para descifrar el contenido del<br />

nido. Sintió el viento de la madrugada arreciar y<br />

la primera claridad llevarse la noche.<br />

Pensó que era hora de volver a casa. Escuchó una<br />

patrulla; alguien había hecho lo correcto: avisar.<br />

Vio por última vez la estatura del árbol vencido<br />

e imaginó el aumento de luz que su ausencia<br />

provocaría en la ventana de la cocina. Eso sería<br />

todo lo que quedaría de aquel árbol: un boquete<br />

como memoria de su sombra. Cerró la puerta<br />

tras de sí, y antes de recostarse junto al plácido<br />

dormir de su marido, entró al cuarto de los niños<br />

24

y colocó su mano con suavidad para comprobar<br />

el vaho de su respiración. Sosegada, prosiguió.<br />

Mañana se enterarían de lo que había ocurrido.<br />

Fingiría sorpresa. No contaría que estuvo allí<br />

sentada en el silencio de la noche, asistiendo al<br />

duelo. Omitiría que la noche fue suya.<br />

25

Author’s Note on “<strong>The</strong> <strong>Tree</strong>”<br />

Once I saw a fallen tree in front of the house<br />

where I lived. It was night, the sudden noise<br />

and darkness unusual. I felt a certain complicity<br />

with the rare event, with the tree’s fragility, its<br />

solitude and tragedy. I lived with my husband<br />

and daughters upstairs from the shop that was<br />

my parents’ business, and the image of those<br />

branches embedded in the grating, invading a<br />

section of the parking lot, was powerful. It stayed<br />

with me. I don’t know if I wrote something in a<br />

journal then, but the truth is the event became<br />

the raw material for this story that had to be titled<br />

“<strong>The</strong> <strong>Tree</strong>.” I live in Mexico City, and the city<br />

has its own ways of speaking. It seemed to me<br />

that this was such a moment. I enjoy the idea of<br />

the extraordinary interrupting everyday life, enjoy<br />

exploring fragility, silences. And this story gave<br />

me such an opportunity.<br />

Translated by Patricia Dubrava<br />

26

<strong>El</strong> árbol<br />

Una vez vi al árbol caído frente a la casa donde<br />

yo vivía, era de noche y la oscuridad y el ruido<br />

inusuales. Es cierto que sentí una complicidad<br />

con lo inusitado, con la fragilidad del árbol, con<br />

su soledad y la tragedia. La imagen de las ramas<br />

incrustadas en la reja, invadiendo un pedazo del<br />

estacionamiento de aquella casa donde yo vivía<br />

con mi marido e hijas en la parte de arriba de<br />

una tienda que era negocio de mis padres, fue<br />

muy poderosa. Se quedó allí; no sé si escribí algo<br />

en un diario entonces, lo cierto es que pudo ser<br />

material de este cuento que tenía que tener como<br />

título “<strong>El</strong> árbol”. Vivo en la Ciudad de México,<br />

la ciudad tiene sus maneras íntimas de hablar:<br />

me pareció que este era un momento así. Me<br />

gusta la idea de lo extraordinario irrumpiendo<br />

en la vida de todos los días, me gusta explorar la<br />

fragilidad, los silencios. Y este cuento me dio la<br />

oportunidad.<br />

Mónica Lavín<br />

27

28

Translator’s Note<br />

I generally employ the Gregory Rabassa<br />

method of translation, and read stories as I’m<br />

translating them, so coming upon the Raymond<br />

Carver reference in Mónica Lavín’s “<strong>The</strong> <strong>Tree</strong>”<br />

was a pleasant surprise. I knew Ray Carver in<br />

Sacramento in 1966-1967, when I lived in a<br />

communal house steaming with political and<br />

arts activity, including the publication of an<br />

ephemeral literary magazine called <strong>The</strong> Levee. By<br />

“publication,” I mean we mimeographed the pages<br />

and sat in a circle to collate, fold and staple them.<br />

Ray provided early revision lessons, suggesting<br />

changes to a poem of mine that was to be<br />

included. I was twenty and thought poems came<br />

whole, from divine fountainheads.<br />

I had completed a first draft of “<strong>The</strong> <strong>Tree</strong>” when<br />

I visited Mónica Lavín last summer in Mexico<br />

City. Her Coyoacan living room is covered by<br />

bookshelves to which I am drawn as filings are<br />

to magnets. I immediately recognized the spine<br />

of Where I’m Calling From among the English<br />

language literature on her shelves. “You know,”<br />

I said, “your story is a kind of Carver story,<br />

an homage.” “Really?” She asked. “I hadn’t<br />

thought of that. It’s inspired by something that<br />

happened.” Much fiction is built on something<br />

that happened. And writers don’t always realize<br />

29

all the layers their work has woven. “<strong>The</strong> <strong>Tree</strong>”<br />

is a Mexican woman’s version of a Carver story:<br />

domestic, quiet, with a subtle, solitary epiphany.<br />

<strong>The</strong> challenge on first translating any writer is<br />

becoming acclimated to her vocabulary, syntax,<br />

rhythm—all the things that make up individual<br />

style. Beginning to translate Mónica Lavín was<br />

a challenging climb. Counting “<strong>The</strong> <strong>Tree</strong>,” I’ve<br />

now translated fifteen of her stories. Aspects of<br />

her writing have become familiar in the way they<br />

only can in the process of translation. <strong>The</strong>re is<br />

no closer reading of a text. As Simon Leys said,<br />

“Translation is the severest test to which a book<br />

can be submitted.” I start noticing repetitive<br />

phrasing, particular ways of putting a sentence<br />

together, become better at rendering them, at<br />

being able to say, “I know what she means and<br />

a literal translation won’t work, but I can find a<br />

way to say it in English.”<br />

By the time I returned home from Mexico last<br />

summer, “<strong>The</strong> <strong>Tree</strong>” draft had cooled, and its<br />

inadequacies surfaced, as they do with time. I<br />

completed a second draft and a third. <strong>The</strong>n, months<br />

later, before I sent it out into the world, I revised<br />

it again, the culmination of a technique I began<br />

learning from Ray Carver so many years ago.<br />

Patricia Dubrava<br />

30

31

32