AD 2016 Q2

As we pointed out in the spring 2013 edition of the Alert Diver, even being a dive buddy has potential legal implications. So, to bump this up a notch, what about the diver training organisations themselves? Where do they stand? How do they relate to South African law? Are they all considered the same under our legal system in spite of the differences in organisational structures and training programmes? How does this affect their respective instructors and trainee divers from a legal perspective? These are not exactly simple questions. It is certainly true that the respective training organisations differ in a number of ways. However, this does not imply that there are necessarily differential legal implications for each of them. In fact, under South African law, the legal principles are common in all matters. Therefore, if you suffer a loss and you (or your estate in the case of a fatality) wish to recover damages, the legal principles would be applied commonly; whether you are driving or diving. Although not a frequent occurrence, there have been quite a number of law suits associated with diving injuries and damages in South Africa. This is not surprising, as the occurrence of law suits is really a function of “numbers”. As training increases, so do the chances of injuries and, with it, the chances of legal recourse. So, it remains wise to insure yourself, your equipment or your business in a proper and effective way. But before getting back to the potential differences amongst the training agencies, let’s first explore the foundational legal principles on which any civil claim would be adjudicated: inherent risk, negligence and duty to take care.

As we pointed out in the spring 2013 edition of the Alert Diver, even being a dive buddy has potential legal implications. So, to bump this up a notch, what about the diver training organisations themselves? Where do they stand? How do they relate to South African law? Are they all considered the same under our legal system in spite of the differences in organisational structures and training programmes? How does this affect their respective instructors and trainee divers from a legal perspective? These are not exactly simple questions.

It is certainly true that the respective training organisations differ in a number of ways. However, this does not imply that there are necessarily differential legal implications for each of them. In fact, under South African law, the legal principles are common in all matters. Therefore, if you suffer a loss and you (or your estate in the case of a fatality) wish to recover damages, the legal principles would be applied commonly; whether you are driving or diving.

Although not a frequent occurrence, there have been quite a number of law suits associated with diving injuries and damages in South Africa. This is not surprising, as the occurrence of law suits is really a function of “numbers”. As training increases, so do the chances of injuries and, with it, the chances of legal recourse.

So, it remains wise to insure yourself, your equipment or your business in a proper and effective way. But before getting back to the potential differences amongst the training agencies, let’s first explore the foundational legal principles on which any civil claim would be adjudicated: inherent risk, negligence and duty to take care.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

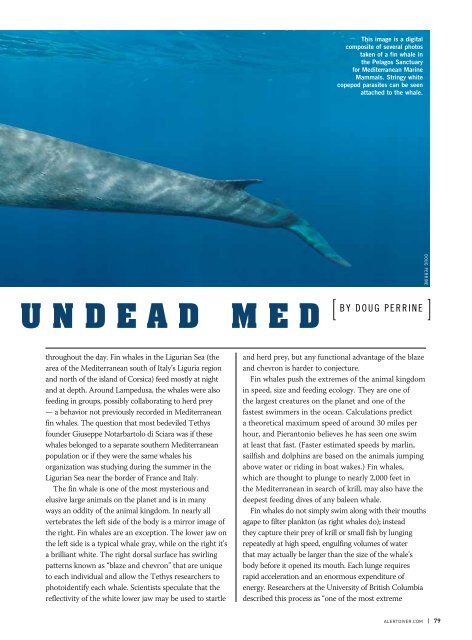

This image is a digital<br />

composite of several photos<br />

taken of a fin whale in<br />

the Pelagos Sanctuary<br />

for Mediterranean Marine<br />

Mammals. Stringy white<br />

copepod parasites can be seen<br />

attached to the whale.<br />

[<br />

BY DOUG PERRINE<br />

DOUG PERRINE<br />

[<br />

throughout the day. Fin whales in the Ligurian Sea (the<br />

area of the Mediterranean south of Italy’s Liguria region<br />

and north of the island of Corsica) feed mostly at night<br />

and at depth. Around Lampedusa, the whales were also<br />

feeding in groups, possibly collaborating to herd prey<br />

— a behavior not previously recorded in Mediterranean<br />

fin whales. The question that most bedeviled Tethys<br />

founder Giuseppe Notarbartolo di Sciara was if these<br />

whales belonged to a separate southern Mediterranean<br />

population or if they were the same whales his<br />

organization was studying during the summer in the<br />

Ligurian Sea near the border of France and Italy.<br />

The fin whale is one of the most mysterious and<br />

elusive large animals on the planet and is in many<br />

ways an oddity of the animal kingdom. In nearly all<br />

vertebrates the left side of the body is a mirror image of<br />

the right. Fin whales are an exception. The lower jaw on<br />

the left side is a typical whale gray, while on the right it’s<br />

a brilliant white. The right dorsal surface has swirling<br />

patterns known as “blaze and chevron” that are unique<br />

to each individual and allow the Tethys researchers to<br />

photoidentify each whale. Scientists speculate that the<br />

reflectivity of the white lower jaw may be used to startle<br />

and herd prey, but any functional advantage of the blaze<br />

and chevron is harder to conjecture.<br />

Fin whales push the extremes of the animal kingdom<br />

in speed, size and feeding ecology. They are one of<br />

the largest creatures on the planet and one of the<br />

fastest swimmers in the ocean. Calculations predict<br />

a theoretical maximum speed of around 30 miles per<br />

hour, and Pierantonio believes he has seen one swim<br />

at least that fast. (Faster estimated speeds by marlin,<br />

sailfish and dolphins are based on the animals jumping<br />

above water or riding in boat wakes.) Fin whales,<br />

which are thought to plunge to nearly 2,000 feet in<br />

the Mediterranean in search of krill, may also have the<br />

deepest feeding dives of any baleen whale.<br />

Fin whales do not simply swim along with their mouths<br />

agape to filter plankton (as right whales do); instead<br />

they capture their prey of krill or small fish by lunging<br />

repeatedly at high speed, engulfing volumes of water<br />

that may actually be larger than the size of the whale’s<br />

body before it opened its mouth. Each lunge requires<br />

rapid acceleration and an enormous expenditure of<br />

energy. Researchers at the University of British Columbia<br />

described this process as “one of the most extreme<br />

ALERTDIVER.COM | 79