Railway_Digest__February_2018

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

oven. It may not be well known that the GE and EMD built locomotives<br />

don’t come standard with these basic creature comforts that would<br />

be expected and taken for granted in the 21st century. An SD70’s<br />

traditional driver’s control stand is very imposing in comparison to the<br />

desktop-mounted controls found on the older GE Dash 9’s, and the<br />

driver is all but hidden from anyone sitting in the observer’s seat on the<br />

opposite side of the cab. But many drivers prefer the control stand as it<br />

allows for a more relaxed driving position, whereas the neater desktop<br />

controls encourage a less comfortable, lean forward posture.<br />

At 5.30pm with the sun close to setting, Geoff receives clearance<br />

from control in Perth to proceed, and the loco throttle is moved to notch 6,<br />

setting the vast load of ore rolling towards the port. A very slight<br />

downgrade assists with forward progress and our train’s speed slowly<br />

builds towards an ambling 25kph. Entering the port balloon loops just 2<br />

km later, the position lights beside the movable frog turnouts indicated<br />

the route was set for our train to take the outer circuit through to the<br />

No. 1 dumper, or TUL 1, situated 3.5 km further on. Several minutes had<br />

passed when the distinctive white compressor cars coupled onto the tail<br />

of the preceding rake were reached. It is certainly a unique experience<br />

to be gradually closing up to another train and leaving just a short space<br />

when there is nearly 40,000 tonnes behind you. However, this is very<br />

normal practice that outsiders would not expect. Naturally, great care<br />

is exercised, there being little tolerance for negligence. Drivers are<br />

very conscious that second chances are rare if it is proven their actions<br />

have led to a costly mishap. It was apparent there would be some time<br />

before our train could enter the dumper with around twenty cars of the<br />

preceding rake still to be tipped.<br />

Once the rake ahead had completed being unloaded and having pulled<br />

clear, the green signal at the entrance to the dumper shed was activated<br />

by the operator in Perth. This indicated it was clear for Geoff to move the<br />

train forward through the very tight confines of the TUL 1 rotary tipper<br />

at a snail’s pace. By tight, I mean clearances for locomotives in the tipper<br />

can be measured in just millimetres. With the first two ore cars correctly<br />

positioned, the shunter promptly uncoupled the locos. As soon as the<br />

compressor cars were attached at the rear to maintain the air needed to<br />

hold off the brakes, the three hour dumping operation could begin. Just a<br />

short distance ahead of our locos were the two compressor cars detached<br />

from the preceding empty rake, which was by now slowly making its way<br />

out onto the main line. It was the task of our locos to push the compressor<br />

cars forward 3.5 kms to the stand point at the end of the balloon loop.<br />

A full time shunt loco attaches the compressor cars to the arriving loaded<br />

rakes, and then collects them again after the departure of empty trains<br />

headed back to the mines. Following the shunt loco coming to take them<br />

off our hands, the way was then cleared for our locomotives to continue<br />

on to the provisioning shed to refuel and receive a quick hose down.<br />

While at the shed I captured images of the activities being<br />

performed. Apparently past refuelling mishaps have led to there being<br />

a 17,000 litre fill limit regardless of the loco type. SD70s and Dash 9s<br />

each have 18,000 litre tanks, but the SD90s have a 21,000 litre capacity.<br />

This difference had occasionally resulted in the unintended over-filling<br />

of the smaller tanks. It was decided that 17,000 litres should become<br />

the standard maximum fill limit to always err on the safe side.<br />

Kanyirri depot itself possess two very large fuel storage tanks capable<br />

of holding six million litres of diesel. Over two million litres of this vital<br />

fuel are transported by rail out to the mines several times a week. In<br />

2014 I saw a 24 fuel wagon consist, which amounts to a substantial<br />

load, with each unit having a tare weight of 37 tonnes and a capacity of<br />

95,000 litres.<br />

Also that night I was offered a special bonus of witnessing up close,<br />

the very intriguing unloading task performed by the rotary tipper in<br />

the TUL 1 shed. This is something that I missed out on seeing in 2014.<br />

Observing the 240 car rake being effortlessly moved forward by the<br />

discreet, but very powerful (1.1MW) indexer arm, with pairs of wagons<br />

being tipped in the dumper every 88 seconds, is mightily impressive.<br />

It is especially amazing when you realise it is all being operated by<br />

someone who is performing the task from Perth, 1,300 km away.<br />

But it is plainly obvious that the very long rakes endure a relatively<br />

violent three hours, with abrupt starting and stopping with each positioning<br />

movement. This is despite the coupler slack being significantly lessened<br />

by the rigid bars connecting the ore cars into permanent pairs. Any<br />

weaknesses in the traditional draw gear are eventually exposed, and it<br />

is very likely they will develop during this unloading operation which<br />

each rake is subjected to, on average, every 24 hours.<br />

When all three dumpers are operating, the delivery of crushed ore<br />

is relentless, typically achieving 500,000 tonnes per day. But as TUL<br />

2 on this occasion was undergoing scheduled maintenance which<br />

was planned to continue at least until 7.30 the next morning, the<br />

daily tonnage total would be greatly impacted. But to coincide with<br />

the reduced delivery capacity at the port, the Christmas Creek mine<br />

loadout was also closed for routine maintenance.<br />

Above left (page 28): Viewed<br />

from the popular tourist friendly<br />

Redbank Bridge vantage point<br />

at Port Hedland, at 12.41pm on<br />

Wednesday 31 August 2016,<br />

BHPBIO’s EMD SD70’s 4424 and<br />

4326 wait beside Rio Tinto’s<br />

evaporative salt pans before<br />

entering Point Nelson yard with<br />

another load of ore being carried<br />

in 268 ore cars. The mid-train<br />

locomotives can be seen in the<br />

distance, 134 cars back.<br />

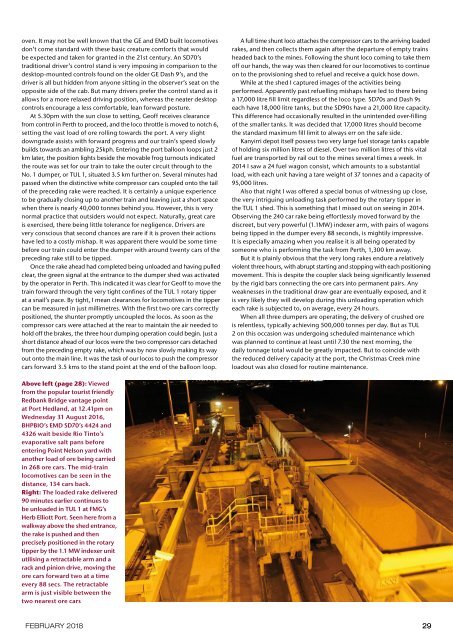

Right: The loaded rake delivered<br />

90 minutes earlier continues to<br />

be unloaded in TUL 1 at FMG’s<br />

Herb Elliott Port. Seen here from a<br />

walkway above the shed entrance,<br />

the rake is pushed and then<br />

precisely positioned in the rotary<br />

tipper by the 1.1 MW indexer unit<br />

utilising a retractable arm and a<br />

rack and pinion drive, moving the<br />

ore cars forward two at a time<br />

every 88 secs. The retractable<br />

arm is just visible between the<br />

two nearest ore cars<br />

FEBRUARY <strong>2018</strong> 29