You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

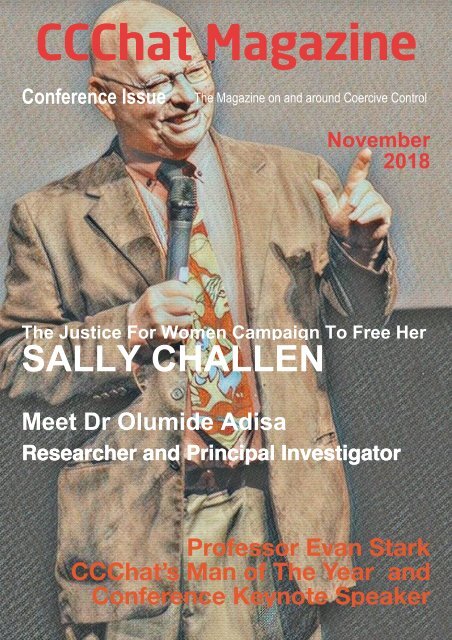

<strong>CCChat</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong><br />

Conference Issue<br />

The <strong>Magazine</strong> on and around Coercive Control<br />

<strong>November</strong><br />

<strong>2018</strong><br />

The Justice For Women Campaign To Free Her<br />

SALLY CHALLEN<br />

Meet Dr Olumide Adisa<br />

Researcher and Principal Investigator<br />

Professor Evan Stark<br />

<strong>CCChat</strong>’s Man of The Year and<br />

Conference Keynote Speaker

Contents<br />

Editor's Notes<br />

3 Blink and You'll Miss.<br />

It's been busy busy busy......<br />

Conference on Coercive Control<br />

5 The Schedule for the day<br />

The <strong>CCChat</strong> interview<br />

9 Professor Evan Stark<br />

Justice For Women<br />

<strong>11</strong> <strong>November</strong> Event<br />

Coercive Control:<br />

Punishment & Resistance<br />

The Spotlight On.....<br />

15 Dr Olumide Adisa<br />

Freedom's Flowers<br />

18 Continuing our serialisation of Pat<br />

Craven's book. This month: Chapter 4 The<br />

Six Year Old<br />

Guest Post<br />

26 Sing-Along-A-Domestic-Abuse?<br />

by Amanda Warburton-Wynn<br />

Making The Invisible Visible

Editor's Notes<br />

About The Editor<br />

Min Grob started conference<br />

on Coercive Control in June<br />

2015, following the end of a<br />

relationship that was coercive<br />

and controlling.<br />

Since then, there have been 4<br />

national conferences three in<br />

Bury St Edmunds and one in<br />

Bristol. The conference on the<br />

34th <strong>November</strong> at Goldsmiths,<br />

University of London will bw<br />

the fift.<br />

Other events have been<br />

planned for 2019 and 2020.<br />

Min is particularly interested<br />

identifying perpetrator tactics<br />

and has spoken on the<br />

challenging subject of<br />

differentiating between strident<br />

discourse and deliberate<br />

baiting.<br />

With the use of examples from<br />

social media, various covert<br />

tactics can be identified<br />

therefore creating greater<br />

awareness and understanding<br />

of our abuse manifests when it<br />

is invisible in plain sight.<br />

Min is also a public speaker<br />

and speaks on topics such as<br />

her personal experiences of<br />

coercive control,,perpetrator<br />

tactics and also more generally<br />

of abuse that is hidden in plain<br />

sight.<br />

In September <strong>2018</strong>, Min<br />

launched Empower - a hub for<br />

supporting and education on<br />

and around coercive control.<br />

Find it on:<br />

www.empowersuffolk.co.uk<br />

Let's grow the Conversation!<br />

Blink and You'll Miss<br />

Hello to all readers of CChat - old and new and welcome to this conference<br />

edition of <strong>CCChat</strong> <strong>Magazine</strong> which, as well as being available online and as a<br />

PDF version will be made available to attendees of the Conference on Coercive<br />

Control as a printed copy.<br />

It's been a really really busy few months planning for the future. Empower, the<br />

local information and support hub for the Waveney area of Norfolk and Suffolk<br />

has launched. It is still in the early stages but dates are already up for coercive<br />

control and stalking training as well as a Freedom Programme Facilitator course<br />

starting next year. There are various events being planned for next year and they<br />

will be added to the site in the coming months. If you are from East Anglia, take a<br />

look at www.empowersuffolk.co.uk and keep checking in to see what's new.<br />

Changes are also afoot for this magazine as it is hoped to include more sections<br />

on wellbeing and managing trauma. As it stands, at the moment, I'm limited to<br />

what I can produce on my own with super-slow rural wifi but hopefully this should<br />

all change soon- watch this space!<br />

One thing I am very excited about is the planning for an event in 2020. It sounds<br />

like a long way off but time goes by so quickly that it feels like each time i blink, 6<br />

months have flown by!<br />

The event is called SMEAR! and it is a look at how and why abusers smear and<br />

how better to identiy it. It will look at tactics such as 'mobbing' and the various<br />

covert ways abusers use others to abuse on their behalf whilst they, the<br />

instigator or ringleader of the abuse, stays in the background. It is a deeper look<br />

at all those situations where the classic response is 'Six of One, Half a Dozen of<br />

the Other'.<br />

Tickets are now available for next year's conference in Liverpool which is being<br />

sponsored by the Freedom Programme and is also partnered with Relate<br />

Cheshire, Merseyside and Greater Manchester,Sam Billingham's SODA and<br />

author Jennifer Gilmour's Abuse Talk Forum .<br />

I'm really really looking forward to what the future brings and hope you'll<br />

accompany me along the way!<br />

To contact Min:<br />

Min x<br />

contact@coercivecontrol.co.uk<br />

Making The Invisible Visible

Conference on Coercive<br />

Control<br />

The Schedule<br />

Schedule for the Day (may be subject to change)<br />

9.15 – 9.45 Registration<br />

9.45 -9.50. Welcome<br />

9.50 -10.00 Opening Speech David Challen<br />

10.00-<strong>11</strong>.30 Keynote Speech Professor Evan Stark<br />

<strong>11</strong>.30-12.00 Coffee<br />

12.00-12.30 Living With Murder Joanne Beverley<br />

12.30- 1.00<br />

1.00-1.30 Trauma Informed Services Dr Suzanne Martin<br />

The Elderly and Coercive Control (tbc)<br />

1.30-2.15 Lunch<br />

2.15-3.15 Cultic Abuse and Coercive Control<br />

Dr Alexandra Stein,<br />

Christian Szurko<br />

Dr Linda Dubrow-Marshall<br />

Dr Rod Dubrow-Marshall<br />

3.15 - 3.45 Online Coercive Control Sarah Phillimore<br />

3.45 --4.15 Post Separation Abuse Dr Laura Monk<br />

4.15- 4.20 Closing Speech<br />

4.20 - 5.00 - Tea and Networking<br />

5.00 ENDS<br />

Making The Invisible Visible

Conference on Coercive Control<br />

LONDON 24th <strong>November</strong><br />

Here's a closer look at the speakers<br />

C<br />

onference<br />

on Coercive Control LONDON will be the first<br />

conference to be held in the capital.<br />

The venue, Goldsmiths, University of London is a public<br />

research university specialising in the arts, design,<br />

humanities, and social sciences. It is a constituent college of<br />

the University of London.<br />

Professor Evan Stark<br />

Professor Evan Stark is a sociologist, forensic social worker and award winning researcher<br />

with an international reputaion. He is author of award winning book, Coercive Control: How<br />

Men Entrap Women in Personal Life - one of the most important books ever written on<br />

domestic abuse and the original source of the coercive control model when the Home<br />

Office widened its definition of domestic violence. Professor Stark played a major role in<br />

the consultation that led to the drafting of the new offence.<br />

Suzanne Martin, PhD<br />

Suzanne Martin, PhD is a Psychotherapist, VAWG specialist and academic with<br />

experience of working in the NHS, HE, voluntary and private sectors and set up the MA<br />

Understanding Domestic Violence and Sexual Abuse at Goldsmiths.<br />

Joanne Beverley<br />

Joanne Beverley is the sister of Natalie Hemming who was brutally murdered by her<br />

partner. The story of how Paul Hemming became the subject of a murder enquiry became<br />

the subject of a Channel 4 documentary Catching a Killer:The search for Natalie<br />

Hemming<br />

David Challen<br />

David Challen is the youngest son of Sally Challen currently campaigning for her appeal of<br />

the murder of his father Richard Challen. Sally killed her husband Richard after a suffering<br />

a lifetime coercive control and physical violence by him. With fresh psychological evidence<br />

and a more developed understanding of coercive control a successful appeal would create<br />

a landmark case.<br />

Alexandra Stein, PhD<br />

Alexandra Stein, PhD is a writer and educator specialising in the social psychology of<br />

ideological extremism and other dangerous social relationships. She is the author of<br />

Terror, Love and Brainwashing: Attachments in cults and totalitarian systems.<br />

Making The Invisible Visible

Conference on Coercive Control<br />

LONDON 24th <strong>November</strong><br />

Here's a closer look at the speakers<br />

(cont)<br />

Christian Szurko<br />

Christian Szurko is the founder of Dialog Centre UK which provides information on<br />

manipulative influence and guides ex members to recovery after spiritual and<br />

psychological abuse.. He is the Review Board Member of the Open Minds Foundation<br />

Dr Linda Dubrow- Marshall<br />

Dr Linda Dubrow- Marshall is a clinical and counselling psychologist. She is co programme<br />

leader for the MSc Psychology of Coercive Control and MSc Applied Psychology<br />

(Therapies) at the University of Salford. She co -founded the Re-Entry Therapy Information<br />

and Referral Network (RETIRN) to provide specialist mental health services in individuals<br />

and families affected by abusive groups and relationships.<br />

Dr Rod Dubrow- Marshall<br />

Dr Rod Dubrow- Marshall is co-programme leader of the MSc Pychology of Coercive<br />

Control and Visiting Fellow in the Criminal Justice Hub at the University of Salford and on<br />

the Board of Directors of the International Cultic Studies Association.<br />

Sarah Phillimore<br />

Sarah Phillimore is a family barrister based in the South West of England and also site<br />

administrator of Child Protection Resource, an online resource aimed at helping anyone<br />

involved in the child protection system by providing up to date information about relevant<br />

law and practice, and contributing to the wider debate about the child protection system.<br />

Dr Laura Monk<br />

Dr Laura Monk has a degree in Person Centred Counselling & Psychotherapy, an MSc in<br />

psychology, a PhD in psychology and behavioural sciences and studied the lack of support<br />

for mothers separated from their children in a context of domestic abuse, developing a<br />

training programme to improve professionals responses to mothers living apart from their<br />

children and works in private practice.<br />

Making The Invisible Visible

the interview<br />

Professor Evan Stark<br />

Professor Evan Stark is the Keynote Speaker for Conference on Coercive Control<br />

LONDON. He is also <strong>CCChat</strong>'s Man of the Year.<br />

<strong>CCChat</strong> managed to interrupt him from his extremely busy schedule to ask him<br />

some questions...<br />

Do you think the ( coercive control) law goes<br />

far enough?<br />

The Scottish ‘offense is better because it includes<br />

all the elements of coercive control in one place,<br />

including sexual abuse and physical violence, and<br />

carries a maximum penalty of 15 years that more<br />

closely reflects the seriousness of the crime. But<br />

what’s really different about Scotland is the<br />

political context, the leadership on this issue that<br />

has come from CPS and the judiciary, and the<br />

fact that the political wind of the women’s<br />

movement at its back. Northern Ireland has a<br />

weaker law. But the Women’s Movement there<br />

may make if work.’<br />

Do you think the law has increased<br />

understanding of cc?<br />

Andy Myhill and his team at the College of<br />

Policing in London have done an amazing job in<br />

adapting training and risk assessments tools like<br />

the DASH to reflect an approach that is historical,<br />

comprehensive and focused on bringing women’s<br />

voices into the evidence gathering process. There<br />

have been more than 1000 convictions under<br />

S76, contrary to what critics predicted. Reports<br />

have continued to increase, showing women are<br />

viewing the justice system as a possible resource.<br />

These are all positive signs. Neither police nor the<br />

specialist services have been resourced<br />

adequately to meet the new demand. And the<br />

government persists in equating coercive control<br />

with psychological abuse. Coercive control is fearbased<br />

context of domination that makes<br />

emotional abuse tortuous. So much to be done.<br />

This is a question I get asked all the time.<br />

Could you please explain why, if men can be<br />

victims of cc, it is a gendered crime?<br />

Look, no one asks if ‘rape’ is gender-based and<br />

yet men are sexually assaulted too. Coercive<br />

control is in all kinds of relational contexts, in<br />

female-to-male as well as same-sex-identified<br />

partners, as well as many institutional setting like<br />

prisons or POW camps.<br />

Where literal bars replace the rules laid out in<br />

many abusive relationships, we don’t consider the<br />

restraints on liberty criminal. In relationships, now<br />

we do.<br />

To be worthy of public notice, restraints on liberty<br />

must be widespread and based on social<br />

vulnerabilities, among which gender stands out in<br />

its significance as a point of vulnerability in<br />

personal life because of its links to love, marriage,<br />

domesticity, child raising and yet property.<br />

We also know that when women are subjected to<br />

coercive control, the co-occurrence of sexual<br />

violence, stalking, reproductive coercion and sex<br />

role stereotyping is extraordinarily high and have<br />

uniquely devastating consequences.<br />

Nothing in the new law privileges women over<br />

men. But by presuming women should be treated<br />

as equal persons, it does give women an<br />

advantage they don’t currently possess.<br />

Making The Invisible Visible

What else would you like to see to<br />

help victims of cc?<br />

Come to my talk and find out. There<br />

are plenty of women who are speaking<br />

up clealy about what they would like<br />

for themselves. Now some personal<br />

questions:<br />

How do you relax?<br />

Not by answering a lot of questions. I<br />

play piano—hard with my current<br />

health problems—exercise, walk, read<br />

novels, watch a lot of NETFLIX<br />

Favourite food?<br />

Dunno…I’m glutton and dairy free. I<br />

luv swiss cheese<br />

Favourite song?<br />

Old Shep by Elvis….I never cried over<br />

my own dog but was always perplexed<br />

by the things men did and did not cry<br />

about<br />

Favourite movie?<br />

So many, so many….Modern Times<br />

Chaplin; Duck Soup, Marx Brothers;<br />

Children of Paradise; The Big Sleep<br />

What do you look forward to when<br />

coming to the U.K.?<br />

Frankly, eating in Edinburgh and being<br />

with my pals from Women’s Aid in<br />

Belfast, Edinburgh, Wales , Glasgow<br />

and my colleagues in Bristol and<br />

friends all over.<br />

Next, the art museums in London and<br />

Edinburgh, And then the Islands.<br />

What would you take with you on a<br />

desert island? (Humans and pets<br />

not allowed!)<br />

I-Phone to learn how to use it and<br />

then, when it ran out, to wonder at it.<br />

Making The Invisible Visible

Justice for Women is a feminist campaigning<br />

organisation that supports, and advocates on<br />

behalf of, women who have been convicted of the<br />

murder of their male abusers.<br />

Established in 1990, they have been involved in a<br />

number of significant cases at the Court of Appeal<br />

that have resulted in women’s original murder<br />

convictions being overturned including Sara<br />

Thornton, Emma Humphreys, Kiranjit Ahluwahlia<br />

and most recently Stacey Hyde.<br />

Making The Invisible Visible

Sally Challen<br />

The Appeal<br />

whilst he forced strict restrictions on her behavior, he himself, would flaunt his money,<br />

have numerous affairs and visit brothels. If she challenged him, he would turn it back on<br />

her and make her feel she was going mad.<br />

Sally killed Richard in 2010 after years of being<br />

controlled and humiliated by him. At the time of her<br />

conviction, ‘coercive control’ was not a crime in<br />

England and Wales, only becoming recognised in law<br />

as a form of domestic abuse in 2015.<br />

Coercive control is a way of understanding domestic<br />

violence which foregrounds the psychological abuse<br />

and can involve manipulation, degradation, gaslighting<br />

(using mind games to make the other person doubt<br />

their sanity) and generally monitoring and controlling<br />

the person’s day-to-day life such as their friends,<br />

activities and clothing. This often leads to the abused<br />

becoming isolated and dependent on the abuser.<br />

It was dramatised very well in Helen’s storyline in<br />

Radio 4’s The Archer’s back in 2016. Sally was only 16<br />

when she met 22 year old Richard. At first he was<br />

charming but gradually the abuse began. He bullied<br />

and belittled her, controlled their money and who she<br />

was friends with, not allowing her to socialise without<br />

him. But, whilst he forced strict restrictions on her<br />

behavior, he himself, would flaunt his money, have<br />

numerous affairs and visit brothels. If she challenged<br />

him, he would turn it back on her and make her feel<br />

she was going mad.<br />

Although Sally did manage at one point to leave<br />

Richard, even starting divorce proceedings, she was so<br />

emotionally dependent on him that she soon returned,<br />

even signing a ‘post nuptial’ agreement he drew up that<br />

denied her full financial entitlement in the divorce and<br />

forbade her from interrupting him or speaking to<br />

strangers.<br />

It was not long after this reunion, that the offence took<br />

place. Sally, so utterly dependent on Richard, wanted<br />

to believe that they could be together, but his<br />

behaviour towards her was increasingly humiliating.<br />

The final straw was when he sent Sally out in the rain<br />

to get his lunch so that he could phone a woman he had<br />

been planning to meet from a dating agency. Sally<br />

returned suspicious and challenged him, he<br />

commanded her not to question him and she struck<br />

him repeatedly with a hammer.<br />

Her defence at trial was diminished responsibility, the<br />

legal team downplayed the abusive behavior of her<br />

husband, Sally was convicted of murder and sentenced<br />

to life imprisonment with a minimum tariff of 22 years,<br />

reduced to 18 at appeal. Despite the death of their<br />

father, Sally’s two sons and all those who knew Sally<br />

and Richard well have supported her recognizing that<br />

she was completely controlled by Richard.<br />

In 2017, Justice for Women submitted new grounds of<br />

appeal to the Criminal Appeal court highlighting new<br />

psychiatric evidence and an expert report showing how<br />

coercive control provides a better framework for<br />

understanding Sally’s ultimate response in the context<br />

of a history of provocation. Unfortunately, permission<br />

to appeal was refused by a judge who read only some<br />

papers.<br />

On 1st March Sally's legal team submitted a renewed<br />

oral application for appeal before three court of appeal<br />

judges. Sally was granted leave to appeal and on 28th<br />

<strong>November</strong> <strong>2018</strong> she will appear in court for her appeal<br />

hearing.<br />

Making The Invisible Visible

Justice for Women<br />

Coercive Control:<br />

Punishment & Resistance<br />

An Event -15th <strong>November</strong> <strong>2018</strong><br />

O<br />

n<br />

28th <strong>November</strong>, Sally Challen will appeal her<br />

conviction for the murder of her abusive husband<br />

Richard, relying on fresh evidence of ‘coercive<br />

control’.<br />

This form of psychological abuse which can involve manipulation, isolation, degradation<br />

and gas-lighting (mind games causing the victim to doubt their own sanity) was dramatised<br />

to critical acclaim in Helen Archer’s storyline in 2016, in Radio 4’s The Archers, gaining<br />

widespread media coverage and raising public awareness.<br />

However, it is still largely misunderstood not only in wider society but also within the<br />

criminal justice system itself. Introduced to English Law in 2015, there have so far been<br />

very few convictions of the perpetrators of this form of abuse and female survivors such as<br />

those represented by Justice for Women are still persecuted in Court.<br />

Emma-Jayne Magson and Farieissia (Fri’) Martin have both lodged appeals against the<br />

convictions of the murder of their respective partners. On 22nd <strong>November</strong> an oral<br />

permission hearing will take place for Emma-Jayne’s appeal.<br />

Join us as we discuss our current cases and the legal barriers faced by women who have<br />

killed whilst subject to coercive and controlling behaviour and other forms of abuse.<br />

Speakers will include:<br />

Helen Walmsley-Johnson<br />

Author of ‘Look What You Made Me Do’ a biographical account of surviving coercive and<br />

controlling behaviour.<br />

David Challen<br />

Sally Challen’s son on the campaign to free Sally<br />

Harriet Wistrich<br />

Co-founder of Justice for Women, solicitor for Sally Challen and Fri Martin<br />

Clare Wade QC<br />

Barrister for Sally Challen, Fri Martin and Emma-Jayne Magson<br />

Julie Bindel<br />

Journalist and co-founder of Justice for Women<br />

Louise Bullivant<br />

Solicitor for Emma-Jayne Magson<br />

Joanne Smith<br />

Emma-Jayne Magson’s mother<br />

Chaired by Claire Mawer, barrister and member of Justice for Women<br />

Making The Invisible Visible

Justice For Women Event<br />

Coercive Control:<br />

Punishment and Resistance<br />

When:<br />

Thursday 15th <strong>November</strong> <strong>2018</strong><br />

Where:<br />

Phoenix Centre, Phoenix Place, London<br />

WC1X 0DG<br />

Tickets £5 (including wine)<br />

For tickets go to:<br />

www.justiceforwomen.org.uk<br />

or EventBrite<br />

Making The Invisible Visible

Spotlight on<br />

Dr Olumide Adisa<br />

Dr Olumide Adisa of University of Suffolk, has a cross-disciplinary<br />

research experience straddling both economics and sociology.<br />

Prior to joining the University of Suffolk in March<br />

2017, Olumide worked as the Research Lead<br />

examining live at home schemes in the UK and the<br />

role of third sector partnership working at the<br />

Methodist Homes in helping older people live<br />

independently in their homes.<br />

Olumide has held various senior management<br />

positions in the voluntary sector in the UK and<br />

overseas over the last 10 years.<br />

She completed her PhD in economic sociology at<br />

the University of Nottingham in 2016. Her<br />

doctoral thesis primarily applied statistics and<br />

econometric modelling to investigate and<br />

understand the determinants and the health<br />

consequences of economic vulnerability amongst<br />

ageing households in West Africa - using the<br />

NGHPS dataset collected by the World Bank and<br />

NBS in 2004 and 2010.<br />

She is extending the use of these household<br />

datasets to explore other health equity and<br />

vulnerability issues. Olumide has a crossdisciplinary<br />

research experience straddling both<br />

economics and sociology. Her core specialisms are<br />

in applying economic and sociological methods in<br />

the fields of domestic abuse, social exclusion,<br />

health equity, and economic development.<br />

She also teaches and contributes to development<br />

economics and research methodology courses.<br />

Olumide is a member of the Suffolk Institute for<br />

Social and Economic Research. She currently<br />

works on a range of projects as a principal<br />

investigator.<br />

Examples of Olumide's ongoing projects:<br />

Evaluating the money advice for survivors of<br />

domestic abuse, in partnership with Anglia Care<br />

Trust - completed April <strong>2018</strong>.<br />

Access to Justice: Assessing the Impact of the<br />

Magistrates' Court Closures in Suffolk - report<br />

launched in July <strong>2018</strong>, with Suffolk's Public Sector<br />

Leaders.<br />

Evaluating a social mobility pilot project in<br />

Suffolk, in partnership with four secondary<br />

schools and Suffolk County Council.<br />

Evaluating the Norfolk and Suffolk “Project<br />

SafetyNet” pilot service for migrant domestic<br />

abuse victims.<br />

The Venta project: working with male<br />

perpetrators of VACC (violence, abuse, coercion,<br />

and control), in partnership with Iceni.<br />

Evaluating the economic justice project --- routine<br />

screening for economic abuse into the delivery of<br />

domestic violence services (partners: Surviving<br />

Economic Abuse and Solace Women's Aid)<br />

Public Perceptions of the VCSE sector in Suffolk,<br />

in partnership with Commuity Action Suffolk -<br />

completed September <strong>2018</strong>.<br />

Evaluation of the Satellite Refuge Project -<br />

Suffolk. Assessing the confidence levels of charity<br />

managers (risk, governance, and compliance to<br />

regulations) - completed September <strong>2018</strong>.<br />

Making The Invisible Visible

Outside of academia, Olumide boasts a successful<br />

bid portfolio of over a million pounds with major<br />

funders including: BIG Lottery Funding, Heritage<br />

Lottery Fund BBC Children in Need to support the<br />

work of various local,national and international<br />

charities.<br />

Olumide sits on the board of an international<br />

development organisation, Institute of Voluntary<br />

Sector Management providing research and<br />

strategic input; and as a consultant, she has<br />

worked with a grassroots Indian nongovernmental<br />

organisation, the Society for<br />

Development through Education, to empower<br />

Adivasi tribes.<br />

In her spare time, Olumide is managing editor of<br />

the Suffolk Research Blog, an initiative supported<br />

by the Suffolk Foundation Board.<br />

Recent Reports and Publications:<br />

Adisa O. (<strong>2018</strong>). Why are some older<br />

persons economically vulnerable and<br />

others not? The role of socio-demographic<br />

factors and economic resources, Ageing<br />

International (accepted).<br />

Adisa O. (<strong>2018</strong>). Third sector partnerships<br />

for older people: insights from live at home<br />

schemes in the UK, Working with Older<br />

People.<br />

Adisa O. (<strong>2018</strong>). An evaluation of an<br />

alternative money advice service for<br />

survivors of domestic abuse. Ipswich:<br />

University of Suffolk.<br />

Adisa, O. (<strong>2018</strong>). Access to Justice: Assessing<br />

the Impact of the Magistrates' Court<br />

Closures in Suffolk. Ipswich: University of<br />

Suffolk.<br />

Adisa, O. (2016). The determinants and<br />

consequences of economic vulnerability<br />

among urban elderly Nigerians. PhD thesis,<br />

University of Nottingham.<br />

Making The Invisible Visible

Making an Impact: Valuing the Social and<br />

Economic worth of the Voluntary and Community<br />

Sector, Liverpool, June <strong>2018</strong><br />

Centre for Violence Prevention <strong>2018</strong><br />

Annual Conference, Violence Prevention at the<br />

Intersections of Identity and Experience,<br />

Worcester, June <strong>2018</strong><br />

Speaker and Organiser; “Money Matters:<br />

Changing the lives of survivors of domestic abuse<br />

in Suffolk”, March <strong>2018</strong><br />

The Determinants and consequences of<br />

economic vulnerability amongst elderly<br />

people in Nigeria: Evidence from a national<br />

household survey. University of Bielefeld,<br />

Germany (August 1- 8, 2017).<br />

Suffolk Domestic Abuse Partnership (SDAP)<br />

Presentation; “Data Sharing Agreements and<br />

developing a shared database on domestic abuse”;<br />

December 2017.<br />

Adisa, O (2016). Mapping third sector<br />

partnerships in live at home schemes to foster<br />

learning and growth. Policy and Research Unit;<br />

Derby, Methodist Homes.<br />

Adisa, O. (2016). A two-year review of the<br />

HomeWard Project: A partnership between<br />

MHA’s Horsforth Live at Home Scheme & the<br />

British Red Cross: Leeds. Methodist Homes.<br />

Interviewing vulnerable groups - depth<br />

interviewing skills workshop, University of<br />

Suffolk, December 2017<br />

A Fuzzy Set Approach to Multidimensional<br />

Poverty Measurement. University of Bielefied,<br />

Germany (August 1- 8, 2017).<br />

Discussant, Access to Justice for Vulnerable<br />

People - International Conference; The Advocate's<br />

Gateway. Inns of Court College of Advocacy.<br />

London. June 2017<br />

In her spare time, Olumide is managing editor of the Suffolk Research<br />

Blog, an initiative supported by the Suffolk Foundation Board.<br />

Adisa, O. (2015). Investigating determinants<br />

of catastrophic health spending among<br />

poorly insured elderly households in urban<br />

Nigeria. International journal for equity in<br />

health, 14(1), 79.<br />

Invited Reviews:<br />

Building Better Societies (2017). Edited by<br />

Rowland Atkinson, Lisa McKenzie, and Simon<br />

Winlow. Policy Press. London School of<br />

Economics and Political Science Review of Books.<br />

Making The Invisible Visible

Freedom’s Flowers<br />

By Pat Craven<br />

Chapter 4- The Six Year<br />

S<br />

tudies<br />

of children aged between the ages of one and six show that if someone plays<br />

with them, talks to them, reads to them and sings to them, they are more successful<br />

at school than children who have been ignored. As the Dominator has ensured that<br />

we have been unable to interact with our children, they may start school at a<br />

disadvantage from which they may never recover. The Dominator has, effectively,<br />

forced us to ignore them for their own safety and to placate him.<br />

Children need role models because we all learn by example. Our children do, indeed, have a role model. They can watch a<br />

giant baby having tantrums to get his own way. They can clearly see that this tactic is successful, so they copy it in nursery<br />

or school. They can be excluded and then we take them to the doctor who can often diagnose ADHD. I want to stress that,<br />

as a mother in this situation, I do not make the connection between the influence of the Dominator and the behaviour of my<br />

child. I visit the doctor in good faith and I gratefully accept the diagnosis. This is clear from the narratives we have included<br />

in this book.<br />

There can also be another factor at work here. If a child is smacked for displeasing an adult, then they are being given a<br />

clear message. The message is that it is acceptable to assault someone who has done something you do not like. This<br />

lesson can also last a lifetime. Children of any age need friends. Friends can teach us how to behave socially, to play,<br />

communicate and share. This is a way to practise how to behave for the rest of our lives. Dominators are Jailers who do not<br />

allow anyone into the house. They cannot bring friends home. Soon, other children do not invite our young children to visit<br />

or play. Children of the Dominator have no friends.<br />

The absence of friends can affect our children in another deeply damaging way. Friends can show us affection. They can<br />

say, “I like you”, “I want to be your friend”. Young children who have been ignored by their mother to keep them safe cannot<br />

get any affection from anywhere else. Children can also get a lot of stimulus and love from their extended family. The Jailor<br />

has also excluded aunts, uncles, grandparents and all their mother’s friends. No one is there for our six-year-old. No one<br />

shows them any love. Rich Dominators also send our children away to boarding school from a very early age. They convince<br />

us, and everyone else, that this is an advantage to the child. I am not the only person to challenge this notion.<br />

George Monbiot, guardian.co.uk, Monday 16 January 2012 .<br />

..The UK Boarding Schools website lists 18 schools which take boarders from the age of eight, and 38 which take them from<br />

the age of seven. I expect such places have improved over the past 40 years; they could scarcely have got worse. Children<br />

are likely to have more contact with home; though one school I phoned last week told me that some of its pupils still see their<br />

parents only in the holidays. But the nature of boarding is only one of the forces that can harm these children. The other is<br />

the fact of boarding.<br />

In a paper published last year in the British Journal of Psychotherapy, Dr Joy Schaverien identifies a set of symptoms<br />

common among early boarders that she calls Boarding School Syndrome. Her research suggests that the act of separation,<br />

regardless of what might follow it, "can cause profound developmental damage", as "early rupture with home has a lasting<br />

influence on attachment patterns".<br />

When a child is brought up at home, the family adapts to accommodate it: growing up involves a constant negotiation<br />

between parents and children.<br />

But an institution cannot rebuild itself around one child. Instead, the child must adapt to the system. Combined with the<br />

sudden and repeated loss of parents, siblings, pets and toys, this causes the child to shut itself off from the need for intimacy.<br />

This can cause major problems in adulthood: depression, an inability to talk about or understand emotions, the urge to<br />

escape from or to destroy intimate relationships. These symptoms mostly affect early boarders: those who start when they<br />

are older are less likely to be harmed....<br />

Making The Invisible Visible

George Monbiot is wrong to assert that children<br />

are accepted from the age of seven. I have just<br />

done an internet search and found several schools<br />

who accept children as young as three!<br />

Young, growing children need regular nutritious<br />

meals to help them to grow and develop. They also<br />

need to learn to eat in the company of others.<br />

When the Dominator is in charge, mealtimes are<br />

fraught with tension and fear. I am reminded of<br />

the occasion when I asked a group of men this<br />

question: “What happens at mealtimes in the<br />

home of the Dominator?” Several gave this<br />

answer, “The food goes up the wall.” As though it<br />

flies up there of its own volition! However, one<br />

man who had learned a lot from my teaching said,<br />

thoughtfully, “In my house I used to throw it at<br />

‘woman height’ so she could clean it up quickly.”<br />

The others then nodded in agreement. I include<br />

this story to remind us all that the Dominator is<br />

never angry and plans every move in advance.<br />

Our children need sleep at this age. They are<br />

growing fast and need to be alert during those<br />

vital early years at school. Sadly, they do not sleep.<br />

They lie awake in terror, listening to the noise and<br />

violence downstairs. They may wet the bed. In the<br />

morning, we hurry them from the house to avoid<br />

the wrath of the Dominator. We may not have the<br />

time to clean and tidy them so we may take them<br />

to school unkempt and smelly.<br />

This can happen in any social group. A friend told<br />

me that her father was a consultant paediatrician,<br />

and this is exactly what happened to her. When<br />

she went to school she had no friends to protect<br />

her, she was not thriving in class and was bullied<br />

mercilessly.<br />

Once again, as the mother, we fail to make the<br />

connection between the bed wetting and the<br />

Dominator, and we take our child to the doctor for<br />

yet more medication!<br />

“In my house I used to throw it at ‘woman height’<br />

so she could clean it up quickly.”<br />

Children in this situation can associate food with<br />

fear and tension. They can develop eating<br />

disorders. They can become too tense to eat, or<br />

may gobble or hoard food. All my associates who<br />

work in refuges have seen children who behave<br />

like this when they arrive, after fleeing from<br />

Dominators.<br />

Nearly every adult I know, who has problems with<br />

food, grew up in a home where they were<br />

terrorised by a Dominator.<br />

Rose again:<br />

...My oldest son said, a few days ago, "Remember<br />

when me and you slept in the car mum? The little<br />

green car?" I am amazed that he could<br />

remember, he was so young. "Remember,<br />

mummy, when dad used to play the banister<br />

game? He would take us to the top of the stairs<br />

and hold us over the banister, dangling us, you<br />

used to scream and cry and tell him to stop but he<br />

wouldn’t. “OUR LIVES ARE SO MUCH BETTER<br />

NOW MUMMY.”<br />

Making The Invisible Visible

My teenage son said to me the other day, “Mum I<br />

remember when dad bought me new trainers and<br />

they did not fit. I was too scared to tell him, so I<br />

wore them too small.”<br />

Rose’s nine-year-old daughter ...<br />

“When we lived with dad, mum was always upset<br />

and sad. That made us sad. Dad used to throw<br />

the food at the wall, because nothing was ever<br />

good enough for him. It was like we never got to<br />

see mum because dad was always shouting at<br />

her. Well, apparently, he was talking, but who<br />

was born yesterday? He used to hang us over the<br />

banister, we used to scream and shout but he<br />

wouldn’t stop. Life is better now we don’t live<br />

with dad. Life is better now because we are<br />

happier, not sad. No one throws stuff at the<br />

walls. No one shouts and gets bullied...<br />

Daisy ... Verbal abuse at bedtime<br />

He would verbally abuse me when I was putting<br />

the children to bed. Literally, I would have the<br />

baby in my arms placing her in her cot, and he<br />

would start on me. I remember thinking how<br />

inappropriate it was, but didn’t want to argue<br />

back or else I would be just as bad as him. All my<br />

children were fitful sleepers and never slept right<br />

through. Looking back I can see why, but at the<br />

time I never made the connection. Bedtime is<br />

supposed to be relaxed and calm, and yet here<br />

they are being put to bed whilst their mummy is<br />

being yelled at. I feel really sad that I let this go<br />

on for so long. Now I am free, I do wonder how<br />

much the four-year-old may have heard whist<br />

she was in bed, supposedly asleep. I worry she<br />

may have woken and heard him ranting at me.<br />

Was she frightened? How did she feel? It doesn’t<br />

bear thinking about.<br />

“He would come in drunk and hang us over the<br />

banister.”<br />

Rose’s <strong>11</strong>-year-old son<br />

Living with my dad was hard. I used to get really<br />

scared and frightened of him. He used to hit<br />

mummy and I had to see it all the time. What<br />

usually happened was that they would argue and<br />

mum would cry. They would go into the front<br />

room and dad used to tell us to go upstairs. I used<br />

to hear banging and dad’s voice saying nasty<br />

things. Mum would scream. Next, dad would tell<br />

us to come down and say to us that he was sorry<br />

and mum was being nasty and doing wrong<br />

things. Dad would go out and we didn’t know<br />

where. He would come in drunk and hang us<br />

over the banister. We would cry and scream<br />

while mum would be crying. Eventually, we<br />

would go to bed but at about one o’clock or two<br />

he would wake me and my older brother up to<br />

watch 18s with him. We would be really tired the<br />

next day and nanny would get us up and ready<br />

for school and take us there. Dad would cheat on<br />

mum with other girls and never actually come<br />

home without being drunk.<br />

The night of his last attack on me I actually ran<br />

into Abigail’s room at one point for protection.<br />

Yes, it was ridiculous, but I ran into a two-year<br />

year olds bedroom for protection. I just thought<br />

he would leave me alone if I was near her. She<br />

was asleep, but he still yelled, “Don’t bring her<br />

into this, get out.” So that was the end of that.<br />

Once his attack was over (it lasted several hours),<br />

and I could hear him sleeping in the spare room,<br />

I was tempted to sleep on the floor of Abigail’s<br />

room to feel safer, but I didn’t in case he caught<br />

me. I am very ashamed of this now, that I would<br />

think a two-year-old could protect me. I should<br />

have been protecting her.<br />

Clearly Rose’s three children remember life with<br />

their father all too clearly.<br />

Making The Invisible Visible

Not being able to show love<br />

This is really hard to explain, but I don’t think I<br />

was able to show my love for my children<br />

properly when I lived with my abuser. Now I<br />

cuddle and tell them how much I love them so<br />

much more. I think, before, it was because they<br />

were a chore that had to be done, before I had to<br />

deal with him.<br />

Throwing Rachel<br />

Rachel was just one year old. Robert and I were<br />

at Abigail’s birthday with my mother and<br />

stepfather. I left Robert with the two children and<br />

went to get some things from the car. When I<br />

returned he shouted at me for leaving him with<br />

“these two”. At this point he threw Rachel at me, I<br />

stumbled backwards and my stepdad caught<br />

Rachel. I was so shocked that he would have an<br />

outburst like this in public, and then I just felt<br />

really scared about going home. I hadn’t really<br />

registered that he had thrown our one-year-old<br />

across to me.<br />

There is no doubt that children and young people<br />

are accepting this distorted view of relationships.<br />

Zero Tolerance Charitable Trust 1998<br />

One in five young men and one in ten young<br />

women think that abuse or violence is<br />

acceptable.<br />

Sugar magazine and NSPCC online survey<br />

(2005)<br />

Teen Abuse survey of Great Britain<br />

4% of teenage girls were subjected to regular<br />

attacks by their partner.<br />

16% had been hit at least once.<br />

31% thought that it was ‘acceptable’ for a boy to<br />

act in an aggressive’ way if his girlfriend has<br />

cheated on him.<br />

“This is really hard to explain, but I don’t think I was able to show my<br />

love for my children properly when I lived with my abuser.”<br />

I think when you are in this kind of relationship<br />

you are so blinkered and so convinced that<br />

everything is normal that you don’t see the harm<br />

that is going on around you. It wasn’t that I<br />

didn’t care about Rachel being thrown, I just<br />

couldn’t think about it because now I was<br />

focusing on how I could placate him before we all<br />

got home alone with him...<br />

Children need to be told the truth. They need the<br />

truth to make sense of their experience of the<br />

world. So when my child asks me, ‘Why is daddy<br />

hitting you?’ I am likely to respond in a variety of<br />

ways. If daddy is listening, as he so often is, I will<br />

deny that he did hit me.<br />

My child has just witnessed this, and now I am<br />

telling them that they cannot believe their own<br />

eyes. I may also say something like, ‘daddy was<br />

only playing’ or ‘daddy is not well’. They may also<br />

hear daddy saying when he does hit me, ‘I am only<br />

doing this because I love you’.<br />

6% girls between 13-19, with an average age of<br />

15, had been forced to have sex with their<br />

boyfriend, and 1 in 3 forgave him and stayed<br />

with him.<br />

Bliss magazine and Woman’s Aid online survey<br />

(2008)<br />

One in four 16-year-old girls know of someone<br />

else who has been hurt or hit by someone they are<br />

dating.<br />

One in six 15-year-old girls and more than one in<br />

four 16-year-old girls who took part in the survey<br />

(27%) have been hit or hurt in some way by<br />

someone they were dating.<br />

When we finally escape from the Dominator he<br />

continues to abuse us and our children by<br />

enlisting the help of statutory agencies.<br />

Clearly, this is sending children a message that if<br />

you love someone you hit them.<br />

Making The Invisible Visible

Daffodil continues her story:<br />

...My ex started a campaign against me which<br />

was designed to get the house and for me to pay<br />

for it through child benefits etc. It had nothing to<br />

do with my child. He got a gullible social worker<br />

on his side. I did not realise the amount of<br />

emotional abuse he was using, and did not<br />

understand what was really happening. I fell in<br />

to his trap. My mother's phase was, “He loads the<br />

gun and then gets others to pull the trigger”.<br />

I started to be investigated on false allegations<br />

which were kept from me, and they used my<br />

mental health as the reasons. The stress was so<br />

bad at the house, I started to stay at work until<br />

my child was in bed asleep, believing that I was<br />

saving him by keeping him away from what was<br />

happening. I was not. He was picking it all up.<br />

He started wetting himself, started taking his<br />

clothes off so he didn't get them dirty, asking for<br />

a nappy back on. He asks me, “When am I going<br />

to live with you?”<br />

My child minder won't have my son on the day he<br />

comes from his father because he is exhausted,<br />

aggressive and whines for the first part of the<br />

afternoon. I have lost over 20% of my wage, so I<br />

have to work fulltime. I have arranged it so I see<br />

my son on two of the three afternoons I have him,<br />

and work long days the rest of the time.<br />

After settling back in, my son almost lets out a<br />

huge breath and starts to relax and breathe and<br />

become a typical five-year-old. This lasts until he<br />

has to go back. The maximum we have, excluding<br />

holidays, is five nights, the shortest is three<br />

nights...<br />

““He loads the gun and then gets others to pull the trigger”.<br />

Just before I left, my parents came over for a<br />

week’s holiday, which was well timed and good<br />

that I didn't go over to them as I was told by my<br />

solicitor and GP that, if I left the area, social<br />

services would go for an emergency application<br />

to remove my child as I was under investigation.<br />

The holiday was without my ex. My son, at the<br />

start, again in my Mum's words, was like a wild<br />

angry animal, and all he would eat was one food<br />

type. By the end of the week, he was getting back<br />

to his normal, happier self. He was a child they<br />

would have been happy not to see again because<br />

of the behaviour. This was his 5th birthday<br />

week...<br />

Later, after Daffodil’s ex had assaulted her and<br />

been let off with a caution, the family courts<br />

ordered shared residence.<br />

...So they split him [my son] 60-40 to me and,<br />

supposedly, 50-50 during holiday times. My son<br />

has stopped concentrating at school. He asks me<br />

not to go to daddy’s. He says he loves him but<br />

doesn't want to spend so much time there. My son<br />

stopped sleeping through the night, started having<br />

nightmares, especially if he was going to his<br />

father’s.<br />

When the Dominator starts to build up to a violent<br />

episode, we mothers try to protect our children by<br />

getting them out of the way. We send them to<br />

their rooms or out to play in the street. Once they<br />

are there, they may join all the other children who<br />

have been sent out to escape from Dominators.<br />

Our children may join together to form gangs.<br />

They already have a lot in common, and they can<br />

start to abuse drugs and alcohol and to break the<br />

law.<br />

Young children will also hear the Dominator call<br />

their mother vile names. Slut and slag are among<br />

the mildest of them. They will learn not to respect<br />

her or any women, even if they do not yet know<br />

what these words mean. Both boys and girls can<br />

share these beliefs.<br />

Lily<br />

...Looking back during our time with our<br />

Dominator, my son's behaviour (he was 10 when<br />

we left) was awful. He was physically violent and<br />

spiteful towards females. He had no respect for<br />

females and would often name call.<br />

Making The Invisible Visible

Since we have been free, his behaviour has<br />

improved a million per cent. He is now 15 and he<br />

is a wonderful kid.<br />

My daughter, who was eight at the time, was<br />

clingy, nervous, shy and extremely manipulative.<br />

Now, at 14, she is confident and outgoing and<br />

naturally comical!! She still has the ability to<br />

wrap males around her little finger. It was a long<br />

and painful journey to get my children to adjust<br />

their behaviour. They fought me all the way<br />

because they had spent so long behaving<br />

inappropriately, but we got there in the end.<br />

My son broke my heart one day last year. He<br />

said to me, "I saw him beat you when he had you<br />

on the bedroom floor and I’m sorry". I asked him<br />

why he was sorry, and he said, "Because I didn’t<br />

help you".<br />

Magnolia<br />

...Peter was sitting next to me in the front seat of<br />

the car. My precious little boy, who I had sworn<br />

would never know abuse, didn’t know what had<br />

hit him when I got together with Michael. He was<br />

three at the beginning of it all, and here we were<br />

three years later, sharing a very rare moment<br />

alone together. I knew I couldn’t say too much, as<br />

bad mouthing Michael wasn’t allowed, and I had<br />

to be careful in case Peter, unwittingly, repeated<br />

anything we spoke about. I put my hand on his<br />

leg and said, “Things will be better when we’re<br />

away from Michael”. I felt so guilty that I’d<br />

exposed my baby to a man who hated him. I<br />

wasn’t allowed to talk to Peter, except to tell him<br />

off, which I usually did to ward off any need for<br />

Michael to punish my son for crimes that Michael<br />

had made up. I couldn’t cuddle him because I<br />

would be accused of not loving Michael’s children<br />

and of having Peter as a favourite. The scapegoat<br />

stepchild had become a very angry little boy.<br />

Dominators scapegoat one child and spoil the others.<br />

They can pretend to love the scapegoat.<br />

They turn the children against one another.<br />

When my daughter was <strong>11</strong>, she asked if she could<br />

learn karate. I asked her why, and she said,<br />

"Because WHEN a man beats me up I can defend<br />

myself. You should have done karate mummy,<br />

then you could have been the one to do the<br />

beating up, and you wouldn’t have got hurt all<br />

the time". Just because children don’t tell you<br />

what they see, doesn’t mean they haven’t seen<br />

it...<br />

Dominators scapegoat one child and spoil the<br />

others. They can pretend to love the scapegoat.<br />

They turn the children against one another. This<br />

can make it even more difficult when we are trying<br />

to leave the relationship.<br />

Michael said Peter had always been like that,<br />

since he turned two, but I couldn’t help thinking<br />

that Michael’s endless criticism, relentless<br />

taunting and horrible physical abuse had shaped<br />

Peter’s temper. Peter had no bond with his twin<br />

stepsisters. He showed no interest at all because<br />

he wasn’t allowed to. Peter looked up at me and<br />

said he liked Michael. I was horrified that he<br />

couldn’t see what a nasty snake Michael was.<br />

He had only ever pretended to like Peter. Peter<br />

had even accepted that he had to wipe his mouth<br />

before he kissed his stepdad. Michael’s children<br />

could kiss him, but he said “Peter was a dribbler”<br />

to justify abruptly shoving his hand in Peter’s<br />

face as he leaned in to say ‘Goodnight’. I felt so<br />

trapped. I knew I had to get us out of there, but I<br />

could tell that Peter would feel I was depriving<br />

him of a daddy if I did...<br />

Making The Invisible Visible

Sunflower<br />

...One of my early memories as an eight-year-old<br />

is being pinned to the wall with my father<br />

twisting my neck chain with a dangling ‘Star of<br />

David’ (symbol of Judaism) and choking me as he<br />

called me ‘a fucking yid bastard’, whilst my<br />

mother wrestled with him to get him off. He<br />

would eventually loosen his hold, leaving me<br />

weak and terrified, to slide down the wall and<br />

land with a thump. I was terrified, but always<br />

defiant. I would always threaten to get even, to<br />

call the police and get him sent to prison. He<br />

would laugh and look at me with contempt and<br />

disgust.<br />

I did call the police. I called them often, in fact,<br />

but the domestic violence laws in the 1950s<br />

supported the principle that ‘the man’s home was<br />

his castle’ and in his castle he ‘could rule as he<br />

saw fit’. So he always won, and I spent my<br />

childhood living in a war zone, which I believed<br />

was ‘normal’.<br />

He had only left a deposit with the promise of<br />

further hire purchase payments. He would laugh<br />

at my torment!<br />

As I result of all this chaos and trauma, I<br />

constantly wet the bed and developed asthma, for<br />

which I was repeatedly hospitalised. I was<br />

labelled a ‘sick child’. My father repeatedly told<br />

me it was from the bastard ‘yid’ side of the family<br />

as such weakness could not stem from his<br />

healthy, strong roots. Every year, I was sent<br />

away for a two-week holiday to Cliftonville in<br />

Margate, Kent.<br />

This charitable act, from the Jewish Board of<br />

Guardians, was instigated by our local doctor ‘to<br />

give my mother a break from her sickly<br />

daughter’. I was bereft.<br />

Although I was away from direct fear, I was<br />

terrified my mother would die, that ‘he’ would kill<br />

her.<br />

“ I did call the police. I called them often, in fact, but the domestic violence laws in the<br />

1950s supported the principle that ‘the man’s home was his castle’ and in his castle he<br />

‘could rule as he saw fit’. So he always won, and I spent my childhood living in a war<br />

zone, which I believed was ‘normal’."<br />

My mother originated from Russian Jews who<br />

had fled Tallinn in the late 1900s to escape<br />

persecution. On a happy day in 1938 she had<br />

been ambling through Hyde Park in London,<br />

over the road from her home, when a good<br />

looking man in his Coldstream Guards uniform<br />

started to talk to her. He was handsome and<br />

charming. This Liverpool lad, of Irish descent,<br />

fitted her dream of a man to love. She certainly<br />

did love him! She loved him through terror,<br />

abuse, violence, betrayal and repeated<br />

abandonment.<br />

My problem was that I wanted my father to love<br />

me too. I thought he did when he took me to Club<br />

Row in the East End of London and paid 50p for<br />

the cutest puppy which I named ’Fluffy’. The poor<br />

dog spent more time with my father’s hands<br />

round her throat while he dangled her out of a<br />

third floor window from our Hackney council<br />

flat. Her eyes would bulge with terror and I<br />

would be screaming as he repeatedly threatened<br />

to drop her from the heights. He would also<br />

return home after his many ‘trips’ away with<br />

lavish gifts like a transistor radio, television or a<br />

record player. Every time he did this I thought,<br />

‘He must love me’. Within months, the bailiffs<br />

would be at the door demanding that the goods<br />

be returned to the store.<br />

I would constantly cry and tell the people in<br />

charge to telephone her. They became sick to<br />

death of me.<br />

They labelled me as difficult and calmed me<br />

down with some sort of sedative. No one ever<br />

listened to my fears!<br />

I would plan his death in my mind constantly.<br />

How I would kill him and how, then, we would be<br />

‘free’. In fact we became ‘free’ when I was around<br />

15 years old and he finally left with his then<br />

current woman. He tried to return, but by this<br />

time I had met my own ‘man of my dreams’ who<br />

punched my father on his attempt to return to the<br />

family home and beat my mother. This ‘man of<br />

my dreams’ was one of two men I married. I<br />

prided myself that I had not followed my<br />

mother’s pattern of abusive men, because after<br />

all I had never been hit! How wrong I was!<br />

Next issue: Chapter 5 - The Teenager<br />

Reproduced with kind permission from Pat<br />

Craven and The Freedom Programme<br />

www.freedomprogramme.co.uk<br />

Making The Invisible Visible

Sing-Along-A-Domestic Abuse?<br />

a paper by:<br />

Amanda Warburton-Wynn<br />

M<br />

usic<br />

is regularly cited as encouraging or condoning domestic violence<br />

and abuse but research so far has focussed on particular types of<br />

music such as hip-hop.<br />

This paper will look at how domestic violence and abuse also<br />

features in a number of mainstream pop music songs.<br />

The United Nations (<strong>2018</strong>) defines violence against women as "any act of gender-based violence<br />

that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual, or mental harm or suffering to women,<br />

including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public<br />

or in private life."<br />

Intimate partner violence refers to behaviour by an intimate partner or ex-partner that causes<br />

physical, sexual or psychological harm, including physical aggression, sexual coercion,<br />

psychological abuse and controlling behaviours.<br />

Sexual violence is "any sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act, or other act directed against a<br />

person’s sexuality using coercion, by any person regardless of their relationship to the victim, in any<br />

setting. It includes rape, defined as the physically forced or otherwise coerced penetration of the<br />

vulva or anus with a penis, other body part or object." (World Health Organisation, <strong>November</strong> 2017).<br />

Almost one third (30%) of all women who have been in a relationship have experienced physical<br />

and/or sexual violence by their intimate partner. Globally as many as 38% of all murders of women<br />

are committed by intimate partners. In addition to intimate partner violence, globally 7% of women<br />

report having been sexually assaulted by someone other than a partner, although data for nonpartner<br />

sexual violence are more limited. Intimate partner and sexual violence are mostly<br />

perpetrated by men against women. (World Health Organisation). The UK Government Violence<br />

Against Women & Girls Strategy 2016-2020 includes stalking as a VAWG crime (Home Office,<br />

2016).<br />

The causes of domestic violence and abuse are complex but most researchers agree that power and<br />

control plays a significant part. The paper Intimate Partner Violence : Causes and Prevention<br />

(Rachel Jewkes, 2012) concludes that two factors seem to be necessary in an epidemiological<br />

sense (for intimate partner violence to occur): the unequal position of women in a particular<br />

relationship (and in society) and the normative use of violence in conflict.<br />

A 2003 study published by the American Psychological Association (APA,contradicts popular notions<br />

of positive catharsis or venting effects of listening to angry, violent music on violent thoughts and<br />

feeling and concluded that songs with violent lyrics increase aggression related thoughts and<br />

emotions and this effect is directly related to the violence in the lyrics (Exposure to Violent Media:<br />

The Effects of Songs With Violent Lyrics on Aggressive Thoughts and Feelings," Craig A. Anderson<br />

and Nicholas L. Carnagey, 2003).<br />

When reporting on domestic abuse or domestic violence, the media is often accused of trivialising or<br />

normalising the acts of perpetrators by using headlines such as ‘Devoted husband killed wife’ (The<br />

Mirror, 2017), and also of victim blaming (‘Woman drank six Jagerbombs in 10 minutes on the night<br />

she was raped and murdered’, The Sun, 2016). But music is one element of the media that routinely<br />

normalises violence, and some songs gain our unwitting collusion along with commercial success.<br />

Making The Invisible Visible

Some genres of popular music are usually linked<br />

with general violence and violence against women<br />

(rap and hip-hop, Drill) or with tales of volatile<br />

relationships (country) and these will be examined<br />

alongside previous research below. Mainstream<br />

‘pop’ music is not usually a platform for songs<br />

around domestic abuse and songs deliberately<br />

tackling the issue generally do not receive<br />

commercial success, this will also be investigated<br />

further below. However, there are several<br />

commercially successful pop-music songs that<br />

reference domestic abuse, violence against<br />

women or domestic homicide in their lyrics that<br />

have not, until now, been scrutinised. When<br />

thinking about violence in music, the main genre<br />

that comes to mind is rap and hip-hop (GANGSTA<br />

MISOGYNY: A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF THE<br />

PORTRAYALS OF VIOLENCE AGAINST<br />

WOMEN IN RAP MUSIC, Armstrong, 2001) Lyrics<br />

describe acts of physical violence, including use<br />

of weapons such as knives and guns and gangrelated<br />

revenge, as an everyday part of life (Bang<br />

Out, Snoop Dogg 2004).<br />

looking at the effect of song portrayals of intimate<br />

partner violence which concluded that the context<br />

in which domestic violence and abuse is displayed<br />

should be considered by the media.<br />

Sexual violence against women is also a recurring<br />

topic for rap (including gangsta-rap) music with a<br />

number of artists using lyrics that appear to<br />

advocate rape as a way to control or punish<br />

women. In the aforementioned Armstrong (1993)<br />

research, the lyrics of 490 songs by thirteen artists<br />

were studied and the paper concluded that 22% of<br />

the songs contained lyrics advocating violence and<br />

misogyny, whilst <strong>11</strong>% included lyrics about rape.<br />

The number of research articles about violence in<br />

rap and hip-hop music suggest this genre is well<br />

known for lyrics describing, and in some cases<br />

appearing to support, violence against women.<br />

The paper The Influence of Rap/Hip-Hop Music:<br />

A Mixed-Method Analysis on Audience<br />

Perceptions of Misogynistic Lyrics and the Issue<br />

of Domestic Violence (Cundiff, 2017)<br />

There are several commercially successful pop-music songs that reference<br />

domestic abuse, violence against women or domestic homicide in their lyrics<br />

that have not, until now, been scrutinised.<br />

Drill music, originating in Chicago in 2010, is a<br />

more recent variation on hip-hop that has caused<br />

concern both in the US and the United Kingdom<br />

where incidents of UK Drill musicians using their<br />

lyrics to incite violence against other Drill music<br />

gangs (so-called diss tracks) caused police to<br />

successfully pursue a court order banning one<br />

group from making music without police<br />

permission. (The Guardian, <strong>2018</strong>) after Drill music<br />

and gang tensions were linked to the deaths of<br />

three young MCs in London in 2017/18 (FACT<br />

<strong>Magazine</strong>, 2017).<br />

Violence against women also features in a<br />

number of rap and hip-hop tracks. The 2010<br />

release ‘Love the way you lie’ by Eminem and<br />

featuring Rihanna has been scrutinised by more<br />

than one expert in the field of violence against<br />

women. Thaller and Messing (2014)<br />

(Mis)Perceptions Around Intimate Partner<br />

Violence in the Music Video and Lyrics for “Love<br />

the Way You Lie”, cite the song and its<br />

accompanying video as an example of music<br />

perpetuating a number of myths around domestic<br />

violence. The song was also used in an<br />

experiment by Franuick, et al., (2017) ‘The<br />

Influence of Non-Misogynous and Mixed<br />

Portrayals of Intimate Partner Violence in Music<br />

on Beliefs About Intimate Partner Violence’<br />

concludes that its survey results indicated a<br />

positive correlation between misogynous thinking<br />

and rap/hip-hop consumption.<br />

Intimate partner/domestic violence/abuse also<br />

features regularly in another musical genre,<br />

specifically country music. Country music was<br />

first recognised by the industry in America in the<br />

early 1940’s. Lyrics usually describe tales of woe<br />

(often with the death of a parent/lover/dog) along<br />

with accounts of bad luck in financial and<br />

romantic affairs.<br />

Sheila Simon (2003) links the popularity of<br />

country music to listeners being able to relate to<br />

the circumstances the singer appears to be<br />

experiencing. Domestic homicide in country<br />

music has featured more than once - Johnny<br />

Cash’s Delia’s Gone for example – with the lyrics<br />

describing a male perpetrator murdering his<br />

female lover, and these songs are usually tinged<br />

with regret and a certain amount of blame placed<br />

on the victim. An increase in female performers<br />

such as the Dixie Chicks in the 1990’s brought<br />

feminism more to the fore in song lyrics with<br />

lyrics celebrating strong women standing up for<br />

their rights (Lorrie Morgan, What Part of No,<br />

1992).<br />

Making The Invisible Visible

The Dixie Chick’s song Goodbye Earl describes a<br />

man who persistently subjects his wife to violence<br />

but his wife is able to flee and implement legal<br />

measures against him. However, when he<br />

breaches the legal restraints she murders him by<br />

poison with the help of a friend. That Earl had to<br />

die, goodbye Earl Those black-eyed peas, they<br />

tasted alright to me, Earl You're feelin' weak? Why<br />

don't you lay down and sleep, Earl Ain't it dark<br />

wrapped up in that tarp, Earl This move towards<br />

female revenge songs may have more in common<br />

with the aforementioned rap and hip-hop music<br />

than the song writers perceive. Country music has<br />

seen a resurgence in popularity in more recent<br />

times (for example, Taylor Swift) and this has<br />

brought with it a new wave of performers talking<br />

about perhaps more modern issues. The transition<br />

of artists from country to pop, such as Taylor<br />

Swift, has continued the theme of feminism and<br />

strong women but with perhaps more awareness<br />

of ways to assert confidence without resorting to<br />

violence.<br />

A hidden track – ‘The blue flashing light’ which<br />

describes a man who verbally and physically<br />

abuses his family, was never released as a single<br />

and the fact that it is hidden (ie not listed on the<br />

track listing) indicates that Travis were not keen<br />

for the song to be known widely. Call me a name<br />

and I'll hit you again You're a slut, you're a bitch,<br />

you're a whore More recently, Hozier, an Irish<br />

singer songwriter who had huge success with the<br />

song ‘Take me to Church’ in 2016, later released<br />

the song ‘Cherry Wine’ (2016) which was<br />

specifically about domestic abuse and the sales<br />

from iTunes downloads of the track went to<br />

domestic violence charities (www.hozier.com/<br />

Cherrywine). Despite the video featuring well<br />

known actress Saiorse Ronan as a victim of<br />

domestic abuse, the song was denied the<br />

commercial success of Take me to Church and was<br />

mainly reported on by Irish media only (The Irish<br />

Times, 2016).<br />

The 1962 album by The Crystals includes the track<br />

‘He hit me (and it felt like a kiss)<br />

Whilst most of the songs cited so far have less<br />

than obvious connotations of violence against<br />

women, some song writers bravely tackle the<br />

issues of abuse head on – an article from AV<br />

Music in 20<strong>11</strong> lists several such examples but<br />

many of these tunes are album tracks or, if<br />

released as singles, were denied mainstream<br />

success. The 1962 album by The Crystals includes<br />

the track ‘He hit me (and it felt like a kiss)’ which<br />

writers Carole King and Gerry Goffin based on the<br />

experiences of their babysitter Little Eva (who had<br />

success with The Locomotion in 1962). However,<br />

the obvious subject matter meant radio stations<br />

were unwilling to play the track and it was denied<br />

any mainstream success (Songfacts).<br />

He couldn't stand to hear me say That I'd been<br />

with someone new, And when I told him I had<br />

been untrue He hit me And it felt like a kiss<br />

Scottish band Travis had several top 40 songs in<br />

the late 1990s and the best- selling album ‘The<br />

man who’ sold over 3.5 million copies.<br />

Thus, it seems that over 50 years on from the<br />

Crystals’ release, music fans and the media are<br />

still reluctant to hear lyrics that deliberately<br />

reference domestic violence even when the singer<br />

has had previous triumph in the charts. Missing<br />

from the compilations of domestic violence<br />

related songs on the internet are more than a few<br />

tracks that did achieve significant commercial<br />

success, despite the lyrics obviously referring to<br />

domestic abuse or domestic homicide. The song<br />

writers in the examples presented here have done<br />

nothing to hide the graphic and violent lyrics yet<br />

the public and the media seem oblivious to the<br />

stories that are being played out. The most<br />

obvious example is Tom Jones’ Delilah - many of<br />

us will have sung along loudly as he<br />

laments Delilah’s fate of being stabbed to death<br />

on her doorstep in revenge for having a<br />

relationship with another man, then begs her to<br />

forgive him. Whilst the song was originally<br />

recorded by PJ Proby, he refused to release it and<br />

Tom’s version reached number 2 in the British<br />

charts in 1968, even receiving an Ivor Novello<br />

award for best song musically and lyrically. Today,<br />

Delilah features on many karaoke lists and is the<br />

unofficial song of Welsh Rugby fans.<br />

Making The Invisible Visible

In such circumstances, a perpetrator may well feel<br />

wronged and claim the trigger was emotional<br />

infidelity. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/<br />

2009/25/part/2/chapter/1/crossheading/partialdefence-to-murder-loss-of-control<br />

Moving to the<br />

1990’s, the lyrics of Animal Nitrate by indie<br />

rockers Suede; describe a relationship with<br />

physical and possibly sexual violence. The band<br />

claimed the song, which reached number 7 in the<br />