photo mag

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

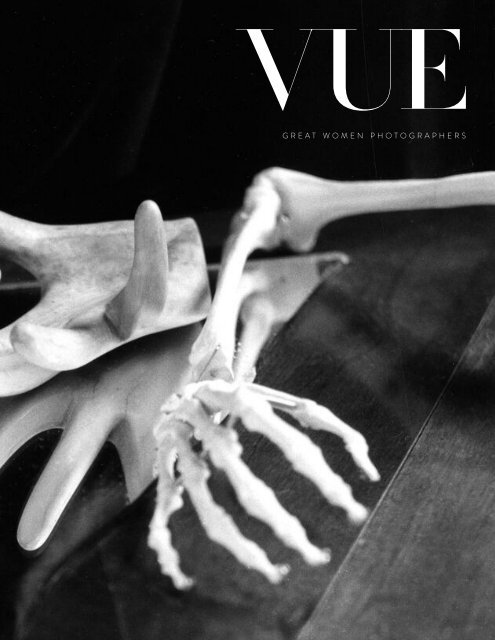

g r e a t w o m e n p h o t o g r a p h e r s<br />

1

2

g r e a t w o m e n p h o t o g r a p h e r s<br />

d e s i g n e d b y<br />

h a n n a k i m

CONTENTS<br />

04<br />

DOROTHEA LANGE<br />

22<br />

VIVIAN MAIER

44<br />

MARGARET BOURKE-WHITE<br />

128<br />

DIANE ARBUS<br />

154<br />

IMOGEN CUNNINGHAM

DOROTHEA<br />

LANGE<br />

8<br />

(MAY 26, 1895 – OCTOBER 11, 1965)<br />

Dorothea Lange was born in Hoboken, New Jersey to Heinrich<br />

Nutzhorn and Johanna Lange. She was an American documentary<br />

<strong>photo</strong>grapher and <strong>photo</strong>journalist, best known for her Depression-era<br />

work for the Farm Security Administration where Lange <strong>photo</strong>graphed<br />

the unemployed men who wandered the streets of San Francisco and<br />

migrant workers. Her portrait <strong>photo</strong>graphy of displaced farmers during<br />

the Great Depression greatly influenced later documentary <strong>photo</strong>graphy.<br />

Dorothea Lange met Paul Taylor, a university professor and labor<br />

Economist. In 1935, they both left their spouses to be with each other.<br />

During the next five years, they traveled together and documented the<br />

rural hardships they encountered for the Farm Security Administration.<br />

Taylor would write poems while Lange <strong>photo</strong>graphed who they met,<br />

including the most well known portrait, “Migrant Mother.”

9

10<br />

THE GREAT DEPRESSION 1930<br />

Men waiting in line for an opportunity at a job during the depression.

11

12

13<br />

WHITE ANGEL BREADLINE 1933<br />

SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA<br />

The failure of the American dream is vividly captured in “White Angel Breadline.” Lange took this famous <strong>photo</strong> in 1933<br />

of a group of hungry men who were gathered outside a soup kitchen on the Embarcadero, near Filbert Street. The feeding<br />

station for the Depression’s poor was created by a widow named Lois Jordan, who called herself White Angel.<br />

Most of the men in the picture have their backs to the camera except for one man with a battered hat and an old trench<br />

coat. Staring bleakly ahead, oblivious of the camera, he is seen cradling a tin cup of soup and folds his hands over a wooden<br />

rail as if in prayer.

14<br />

MIGRANT MOTHER 1936<br />

NIPOMO, CALIFORNIA

15<br />

“WE JUST EXISTED,<br />

WE SURVIVED.<br />

LET’S PUT IT THAT WAY.”<br />

Florence Owens Thompson was born Florence Leona Christie, a<br />

Cherokee, in a teepee in Indian Territory, Oklahoma in 1903. At age<br />

17, she got married and moved to California for farm and millwork.<br />

Thompson became pregnant at 28 with her sixth child and around this<br />

time, her husband died of tuberculosis. From then on, she all kinds of<br />

worked odd jobs to keep her children fed. During cotton harvests, she<br />

would put her babies in bags and carry them along with her as she<br />

worked down the rows, earning 50 cents per 100 pounds picked.<br />

Thompson generally picked around 450,500 pounds a day. In 1963,<br />

while driving from LA to Watsonville, her car broke down and managed<br />

to get it towed into the Nipomo pea-pickers camp. Thompson had the<br />

car repaired and was just about to leave when Dorothea Lange showed<br />

up. She wasn’t eager to have her family <strong>photo</strong>graphed and exhibited<br />

as specimens of poverty, but there were people starving in that camp.<br />

Lange had convinced her that the i<strong>mag</strong>e would educate the public<br />

about the plight of hardworking poor people like herself.<br />

“Migrant Mother” gently and beautifully captured the hardships and<br />

pain of what so many other Americans were experiencing. This iconic<br />

<strong>photo</strong> almost didn’t happen. When Dorothea Lange drove past the<br />

“Pea-Pickers Camp” sign in Nipomo, north of Los Angeles, she kept<br />

going for 20 miles. For the whole 20 miles, there was something<br />

nagging her, finally deciding to turn around. Once the <strong>photo</strong>grapher<br />

spotted Frances Owens Thompson, she knew she was in the right place.<br />

Lange, who believed that one could understand others through close<br />

study, tightly framed the children and the mother, whose eyes, worn<br />

from worry and resignation, look past the camera. She took six <strong>photo</strong>s<br />

with her 4x5 Graflex camera and later wrote, “I knew I had recorded<br />

the essence of my assignment.” After, Lange informed the authorities<br />

of the plight of those at the encampment, and they sent 20,000<br />

pounds of food. Of the 160,000 i<strong>mag</strong>es taken by Lange and other<br />

<strong>photo</strong>graphers for the Resettlement Administration, “Migrant Mother”<br />

has become the most iconic picture of the Depression. Lange gave a<br />

face to a suffering nation.

MARCH 1937<br />

18 year old mother from Olklahoma,<br />

now a California migrant.<br />

16

17<br />

1935<br />

Woman seated with her children at<br />

the entrace of a squatters shelter

18

19

NOVEMBER 1936<br />

KERN MIGRANT CAMP, CALIFORNIA<br />

While the mothers are working in the fields, the<br />

preschool children of migrant families are cared<br />

for in the nursery school under trained teachers.<br />

20

MARCH 1937<br />

CALIFORNIA, NEAR GUADALUPE<br />

Japanese mother and daughter,<br />

agricultural workers.<br />

21<br />

NOVEMBER 1936<br />

CALIFORNIA, NEAR FRESNO<br />

Oklahoma mother of 5 children,<br />

now picking cotton.

NOVEMBER 1940<br />

NEAR COOLIDGE, ARIZONA<br />

Migratory cotton picker with his cotton sack<br />

slung over his shoulder rests at the scales before<br />

returning to work in the field.<br />

22

23

1932<br />

TEXAS<br />

The wife of a migratory laborer with three<br />

children during the Depression.<br />

24

25<br />

1938<br />

SHAFTER, CALIFORNIA<br />

During the cotton strike, the father, a striking picker, has left his wife and<br />

child in the car while he applies to the farm security administration for an<br />

emergancy food grant.

VIVIAN<br />

MAIER<br />

26

27<br />

(FEBRUARY 1, 1926 – APRIL 21, 2009)<br />

Vivian Maier was born in New York City in 1926 and moved to the North Shore<br />

area in Chicago in 1956. During this time, she worked as a nanny and carer for<br />

the next forty years. For the first seventeen years in Chicago, Maier worked for<br />

two families. She was determined to show them the world outside of their affluent<br />

suburb. The families who employed her described her as a very private person who<br />

spent her days off walking the streets of Chicago and taking <strong>photo</strong>graphs, usually<br />

with a Rolleiflex camera. She has taken more than 150,000 <strong>photo</strong>graphs which<br />

were unknown and unpublished during her lifetime and many negatives were never<br />

printed. Children of the nanny later described her, “She was a socialist, a feminist,<br />

a movie critic, and a tell it like it is type of person. She learned English by going to<br />

the theaters, which she loved… She was constantly taking pictures, which she didn’t<br />

show anyone.” From 1959-1960, Vivian Maier took a trip around the world on her<br />

own, <strong>photo</strong>graphing places like Los Angeles, Manila, Bangkok, Shanghai, Beijing,<br />

India, Egypt, and Italy. She kept her belongings at her employers where one held<br />

200 boxes of materials. Mostly <strong>photo</strong>graphs or negatives.<br />

Vivian Maier looked after the Gensburg brothers when they were children. As she<br />

became poorer in old age, they tried to her her. She was about to be evicted from<br />

a cheap apartment in the suburb of Cicero when the Gensburg brothers arranged<br />

for her to live in a better apartment on Sheridan Road in the Rogers Park area of<br />

Chicago. In November 2008, Maier fell on ice and hit her head. She was taken to<br />

the hospital but failed to recover and was transported to a nursing home in Chicago<br />

suburbs where she later died on April 21, 2009.

28

29<br />

In 2007, Maier failed to keep up with payments on a storage space she rented in Chicago’s<br />

North Side. Because of this, negatives, prints, audio recordings, and 8mm film were auctioned<br />

off. Three <strong>photo</strong> collectors, John Maloof, Ron Slattery, and Randy Prow, bought parts of her work.<br />

Vivian Maier’s <strong>photo</strong>graphs were first published on the internet in July 2008 by Ron Slattery<br />

and received little response. John Maloof bought the largest part of Maier’s work which was about<br />

30,000 negatives, later burying more of Maier’s <strong>photo</strong>graphs from another buyer at the same<br />

auction. In October 2009, John Maloof was working on a book about the history of the Chicago<br />

neighborhood of Portage Park. He liked his blog to a selection of Maier’s <strong>photo</strong>graphs on Flickr<br />

which went viral. Thousands of people expressed interest and attracted critical acclaim. Since<br />

then, the <strong>photo</strong>graphs have been exhibited around the world, receiving international attention<br />

in mainstream media.

30<br />

1949<br />

FRANCE<br />

Vivian Maier began toying with her first <strong>photo</strong>s. Her camera was a modest Kodak Brownie box camera, an amateur camera with only one<br />

shutter speed, no focus control, and no aperture dial. The viewer screen is tiny, and for the controlled landscape or portrait artist, it would<br />

arguably impose a wedge in between Vivian and her intentions due to its inaccuracy. Her intentions were at the mercy of this feeble machine.<br />

In 1952, Vivian purchases a Rolleiflex camera to fulfill her fixation.

31<br />

1956<br />

In 1956, when Maier moved to Chicago, she enjoyed the luxury of a darkroom as well as a private bathroom. This allowed her to process her<br />

prints and develop her own rolls of B&W film. As the children entered adulthood, the end of Maier’s employment from that first Chicago<br />

family in the early seventies forced her to abandon developing her own film. As she would move from family to family, her rolls of undeveloped,<br />

unprinted work began to collect.

32

33

34<br />

1950<br />

CHICAGO, ILLINOIS

1953<br />

NEW YORK, NEW YORK<br />

EAST 78TH STREET & 3RD AVE.<br />

CHRISTMAS EVE<br />

35

MAY 5, 1955<br />

NEW YORK, NEW YORK<br />

36

37

MARCH 1954<br />

NEW YORK, NEW YORK<br />

MARCH 1954<br />

NEW YORK, NEW YORK

39

40<br />

OCTOBER 8, 1954<br />

NEW YORK, NEW YORK

41<br />

1954<br />

NEW YORK, NEW YORK

42

JUNE 27, 1959<br />

ASIA<br />

43

JUNE 5, 1959<br />

THAILAND<br />

44

JUNE 27, 1959<br />

ASIA<br />

45<br />

1959<br />

SAIGON, VIETNAM

46

MARGARET<br />

BOURKE-WHITE<br />

47<br />

(JUNE 14,1904 – AUGUST 27,1971)<br />

Margaret Bourke-White was born in Bronx, New York in 1904 and attended<br />

Clarence H. White School of Photography in 1921-1922. She graduated from<br />

Cornell University with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1927. Bourke-White left<br />

behind a <strong>photo</strong>graphic study of the rural campus for the school’s newspaper<br />

which included <strong>photo</strong>s of her dormitory at Risely Hall. She moved to Cleveland,<br />

Ohio where she started a commercial <strong>photo</strong>graphy studio and began concentrating<br />

on Architectural and industrial <strong>photo</strong>graphy. Her success was due to her skills<br />

with both people and her technique. Her work caught the attention of Henry<br />

Luce who hired her in 1929 and sent her to the Soviet Union the next year. She<br />

was the first foreign <strong>photo</strong>grapher to take <strong>photo</strong>s of the Soviet Industry. She<br />

<strong>photo</strong>graphed the Dust Bowl for Fortune in 1934 and in the fall of 1936, Henry<br />

Luce offered Bourke-White a job as a staff <strong>photo</strong>grapher for his newly conceived<br />

Life <strong>mag</strong>azine. She was one of the first four <strong>photo</strong>graphers hired and her <strong>photo</strong>graph<br />

of Fort Peck Dam was reproduced on the first cover.<br />

Throughout World War II, Margaret Bourke-White produced a number of <strong>photo</strong><br />

essays on the turmoil in Europe. She was the only Western <strong>photo</strong>grapher to witness<br />

the German invasion of Moscow in 1941, she was the first woman to accompany Air<br />

Corps crew on bombing missions in 1942, and she traveled with Patton’s army through<br />

Germany in 1945 as it liberated several concentration camps. During the next twelve<br />

years, she <strong>photo</strong>graphed major international events and stories, including Gandhi’s fight<br />

for Indian independence, the unrest in South Africa, and the Korean War. Bourke-White<br />

contracted Parkinson’s disease in 1953 and made her last <strong>photo</strong> essay for Life in 1957.

48<br />

Margaret Bourke-White’s <strong>photo</strong>journalism demonstrated her<br />

ability to communicate the intensity of major world events while<br />

respecting formal relationships and aesthetic considerations.

49

50<br />

“TO ME... INDUSTRIAL FORMS WERE ALL<br />

THE MORE BEAUTIFUL BECAUSE THEY<br />

WERE NEVER DESIGNED TO BE BEAUTIFUL.”

51<br />

OTIS STEEL MILL 1930<br />

CLEVELAND<br />

People wondered if Margaret Bourke-White and her delicate camera<br />

could stand up to the intense heat, hazard, and generally dirty and gritty<br />

conditions inside a steel mill.<br />

Black and white film at the time was sensitive to blue light, not the red<br />

and orange lights that came from hot steel. All of her <strong>photo</strong>s would<br />

come out black but she solved the problem by bringing along a new style<br />

of <strong>mag</strong>nesium flare which produced white light. She had an assistant hold<br />

them to light her scenes. This resulted in some of the best steel factory<br />

<strong>photo</strong>graphs of that era and earned national attention.

52

FORT PECK DAM 1936<br />

FORT PECK, MONTANA<br />

Life <strong>mag</strong>azine printed Bourke-White’s <strong>photo</strong>graph on the cover<br />

of its first issue on November 23. It solidified Fort Peck Dam’s<br />

status as an icon of the machine age.<br />

53

54

55<br />

GREAT OHIO RIVER FLOOD 1937<br />

LOUISVILLE, KENTUCKY<br />

Men and women line up seeking food and clothing from a relief station,<br />

in front of a billboard proclaiming, “World’s Highest Standard of Living.”

56<br />

STALIN 1941

1931<br />

Ekaterina Dzhugashvili, the mother of Russian<br />

leader Joseph Stalin, seated on park bench.<br />

57<br />

1931<br />

Joseph Stalin’s great aunt, Dido-Lilo Dzhugashvili.

APRIL 1945<br />

WEIMAR, GERMANY<br />

Survivors gaze at <strong>photo</strong>grapher Margaret Bourke-White<br />

and rescuers from the United States Third Army during<br />

the liberation of Buchenwald<br />

58

BUCHENWALD<br />

59

APRIL 1945<br />

WEIMAR, GERMANY<br />

Prisoners at Buchenwald gaze from behind barbed<br />

wire during the camp’s liberation by American forces.

61

APRIL 1945<br />

WEIMAR, GERMANY<br />

Deformed by malnutrition, a Buchenwald<br />

prisoner leans against his bunk after<br />

trying to walk. Like other imprisoned<br />

slave laborers, he worked in a Nazi<br />

factory until tee feeble.<br />

62<br />

APRIL 1945<br />

WEIMAR, GERMANY<br />

Examining Buchenwald prisoners after the<br />

camp’s liberation by U.S. troops.

63<br />

APRIL 1945<br />

WEIMAR, GERMANY<br />

A Czech doctor (right) prepares to examine a Buchenwald concentration<br />

camp inmate while other inmates surround him, awaiting treatment.

APRIL 1945<br />

WEIMAR, GERMANY<br />

Prisoners, too emaciated to walk, at Buchenwald<br />

during the camp’s liberation by American forces.<br />

64

APRIL 1945<br />

WEIMAR, GERMANY<br />

Prisoners at Buchenwald during the<br />

camp’s liberation by American forces.<br />

65

66<br />

APRIL 1945<br />

WEIMAR, GERMANY<br />

Prisoners at Buchenwald display their identification<br />

tattoos shortly after camp’s liberation by Allied forces.

67<br />

APRIL 1945<br />

WEIMAR, GERMANY<br />

A newly liberated prisoner stands beside a<br />

pile of human ashes and bones, Buchenwald.

68

APRIL 1945<br />

WEIMAR, GERMANY<br />

German civilians are forced by American troops to bear<br />

witness to Nazi atrocities at Buchenwald concentration<br />

camp, mere miles from their own homes.<br />

69

APRIL 1945<br />

WEIMAR, GERMANY<br />

As German officers and Weimar civilians bear witness, after Buchenwald’s<br />

liberation, to atrocities committed at the camp, a dummy in striped prisoner<br />

garb hangs from a gallows, a gruesome demonstration of one of the many<br />

public ways that inmates were murdered at the camp.<br />

70

APRIL 1945<br />

WEIMAR, GERMANY<br />

The remains of an incinerated prisoner<br />

inside a Buchenwald cremation oven.<br />

71<br />

APRIL 1945<br />

WEIMAR, GERMANY<br />

German civilians are forced by<br />

American troops to bear witness<br />

to Nazi atrocities at Buchenwald<br />

concentration camp, mere miles<br />

from their own homes.

72

APRIL 1945<br />

WEIMAR, GERMANY<br />

The dead at Buchenwald, piled high<br />

outside the camp’s incinerator plant.<br />

73

1948<br />

Mohandas K. Gandhi just a few<br />

hours before his assassination<br />

74

75

THE GREAT MIGRATION 1947<br />

Millions of people fled shortly after the creation<br />

of the nations of India and Pakistan<br />

77

THE GREAT MIGRATION 1947<br />

Mass migration during independence<br />

of India and Pakistan in 1947

79

80<br />

1947<br />

Mosque within fort also packed with homeless moslems.<br />

The great dome provides a measure of shelter against<br />

the elements for some of the refugees.

1947<br />

Spindly but determined old Sikh, carrying ailing wife,<br />

sets out on the dangerous journey to India’s border<br />

81<br />

1947<br />

This strange litter was devised to carry ages and<br />

exhausted Moslem woman, sitting in a sheet with<br />

legs drawn up. The bamboo pole is supported by her<br />

brother-in-law and her son. When this <strong>photo</strong>graph<br />

was made, the family had been four days without food,<br />

but men were managing to keep up with the convoy.

82

1947<br />

Misery of the dispossessed is reflected in the face of<br />

this Moslem boy, perched on the wall of the Purana<br />

Qila fortress in New Delhi. Below him throusands of<br />

his unhappy fellows who had fled their homes in terror,<br />

are trying to survive until they can organize a convoy<br />

for the long march to Pakistan. In their squalid city of<br />

tents and lean-tos they have almost no room to sleep<br />

and little to eat. Surrounded by filth and many will die<br />

without ever leaving camp.<br />

83

85

1947<br />

Abandoned at roadside because they were unable to keep up<br />

with caravan, this Moslem couple and their four grandchildren<br />

have little hope of survival. The children’s father was killed by<br />

Sikhs. Their mother was stricken with cholera and sent ahead<br />

by truck in the hope that she might find medical care.

87

1947<br />

The emigrant trains of crude wooden carts drawn by bullocks creak across the<br />

barren land of the Punjab all day long. In this convoy, starkly silhouetted against<br />

the vivid Indian sky, are 45,000 uprooted Sikhs on their way to the Ferozepore<br />

and Ludhiana districts of the eastern Punjab. Unlike the U.S. wagon-train pioneers,<br />

hopefully en route to a new land, these migrants have little to look forward to and<br />

are losing everything that they cannot carry with them. Despite the presence of an<br />

escort of Gurkha soldiers, thousands of stinking bodies along the road constantly<br />

remind the travelers that they may never reach safety.

89<br />

1947<br />

Mother and child are part of caravan 25 days on road. More fortunate than<br />

most, women can ride and has an umbrella for shade as she feeds her baby.

1947<br />

As the bitter migration goes on a Moslem family<br />

pauses to bury a child who died of starvation.<br />

90

91

1947<br />

Moslem refugee cholera patients in filthy conditions at Infectious Disease<br />

Hospital upon their arrival after their long march from Delhi, India.

93<br />

1947<br />

Moslem refugee cholera patient with child, getting intravenous glucose<br />

solution in the infusion room at Infectious Disease Hospital.

94

APARTHEID 1950<br />

SOUTH AFRICA<br />

South Africans holding a “STOP POLICE TERROR” banner listen to<br />

a speaker during a Communist meeting. The Communist Party of South<br />

Africa was a small but influential opposition group. It was especially active<br />

in labor organizing. It was an inter-racial organization, some of whose<br />

African members were also members of the African National Congress.<br />

95

96

97<br />

APARTHEID 1950<br />

SOUTH AFRICA<br />

During a Communist meeting, carpenter Phillip Mbhele, wearing “WE DON’T WANT PASSES” tag, angrily<br />

speaks against the white Afrikaner’s pass system, which requires all Natives to carry one or more passes.<br />

Passes were a kind of internal passport that africans had to carry anytime they were outside of the so-called<br />

Native Reserves. They were universally hated as symbols os dispossession.

1950<br />

SOPHIATOWN, SOUTH AFRICA<br />

Black children with “EDUCATE THE CHILDREN AND SAVE THE RACE” banner sing a song<br />

during an event at Sophiatown Native Location. Sophiatown was a racially mixed but mostly<br />

black neighborhood near central Johannesburg. It had achieved near-legendary status as a<br />

center of black culture and politics from the 1930s to the ‘50s. The government bulldozed it<br />

in the mid-50s and moved its residents to Soweto, on the far outskirts of town.

99<br />

1950<br />

SOUTH AFRICA<br />

Young dwellers of a shanty-town stand at the fence that marks the boundaries<br />

of their home. Shanty-towns like this one, on the outskirts of Johannesburg,<br />

were formed by homeless black squatters with nowhere else to go.

100<br />

1950<br />

JOHANNESBURG, SOUTH AFRICA<br />

Gold miners nos. 1139 and 5122, both Mndaus, stand sweating in 95 degree heat<br />

of a tunnel in Johannesburg’s Robinson deep mine, more than a mile underground.

101<br />

1950<br />

JOHANNESBURG, SOUTH AFRICA<br />

Gold miners, wearing helmets and very high knee pads, perspire heavily while walking in 95 degree heat<br />

to their jobs, working in a dangerous area in Robinson Deep mine tunnel, more than a mile underground.

102<br />

1950<br />

JOHANNESBURG, SOUTH AFRICA<br />

View of barefoot miners as they sit over the edge of a landing that<br />

overlooks a courtyard in the Robinson Deep mine compound.

1950<br />

JOHANNESBURG, SOUTH AFRICA<br />

Miner’s barrack at the Robinson Deep mine provides concrete<br />

bunks for as many as 40 men in a single room. Barracks like<br />

this are usually kept clean and orderly. Penning men together<br />

away from families is a system that breeds homosexuality.<br />

103

104

SOUTH AFRICA AND ITS PROBELM 1950<br />

105

106<br />

1950<br />

MOROKA, SOUTH AFRICA<br />

Poor native woman fills a can with water at public faucets set up in the middle of Moroka, which housed<br />

60,000 black workers on the outskirts of town. The Moroka township, established in 1947 as a place to<br />

relocate Africans away from central Johannesburg, was known for its appalling conditions.

1950<br />

SOUTH AFRICA<br />

Young workers.<br />

107

108<br />

1950<br />

SOUTH AFRICA<br />

Tot System lets cape winegrowers pay workers partly<br />

in “tots” of wine. Here, a farmer’s daughter serves a<br />

noonday ration to a boy working in the field.

109<br />

1950<br />

SOUTH AFRICA<br />

A young farm worker drinks his “tot,” the<br />

wine that comprised part of his wages and<br />

also led, for many, to alcoholism.

1950<br />

SOUTH AFRICA<br />

Two men at a bar. Alcoholism, a result of the Tot<br />

System, was a major problem among farmworkers.<br />

1950<br />

SOUTH AFRICA<br />

The roots of the Tot System, which led to problems<br />

with alcoholism, go back to the days of slavery. Settler<br />

farmers provided tots of wine periodically throughout<br />

the day to their slaves to induce dependency as a form<br />

of control. After emancipation, workers were paid partly<br />

in wine for the same reason.

111<br />

1950<br />

SOUTH AFRICA<br />

A man drinking.

APRIL 1950<br />

SOUTH AFRICA<br />

Grape pickers working at the farm Ryssel.

113<br />

APRIL 1950<br />

SOUTH WEST AFRICA<br />

African native minders digging in the mine<br />

workings to remove diamond-bearing gravel<br />

from marine terraces where it is deposited.

THE FORGOTTEN WAR JULY 1950<br />

KOREA<br />

The 1st cavalry in Korea.<br />

114

115

1952<br />

KOREA<br />

An American serving in Korea.<br />

116

117<br />

1951<br />

KOREA<br />

An American military man takes a nap.

1952<br />

KOREA<br />

South Korean and American<br />

officers pore over maps.<br />

118

119<br />

NOVEMBER 1952<br />

KOREA<br />

Bullets and gunpowder.

1952<br />

KOREA<br />

Wounded South Koreans.<br />

120<br />

1951<br />

KOREA<br />

Turkish soldiers attend<br />

to a wounded prisoner.

MARCH 1951<br />

KOREA<br />

Refugees cross into South Korea.<br />

121

1952<br />

KOREA<br />

Troops on patrol in Korea.<br />

122

123<br />

1952<br />

KOREA<br />

South Korean troops.<br />

JUNE 1952<br />

KOREA<br />

Three soldiers.

124

JUNE 1952<br />

KOREA<br />

Margaret Bourke-White shares<br />

a meal with South Korean troops<br />

in the field.<br />

125

126<br />

1952<br />

KOREA<br />

Slaughtered South Korean<br />

prisoners and peasants.

127<br />

1952<br />

KOREA<br />

A member of the South Korean National Police holds the severed<br />

head of a North Korean communist guerrilla during the Korean War.

1951<br />

KOREA<br />

Turkish Army soldier on duty.

129<br />

1953<br />

KOREA<br />

Fighter jets, F-86 Sabres, from the Fifth Air Force. The Korean<br />

War was the first conflict in which the Sabre saw action.

DIANE<br />

ARBUS<br />

130

131<br />

(MARCH 14, 1923 – JULY 26, 1971)<br />

Diane Arbus was born Diane Nemerov in New York City. She is an American<br />

<strong>photo</strong>grapher noted for her <strong>photo</strong>graphs of marginalized people such as dwarfs,<br />

giants, transgender people, nudists, circus performers, and others whose normality<br />

was perceived by the general society as ugly or surreal. While growing up, her parents<br />

weren’t involved in her life. She and her siblings were raised by maids and governesses<br />

while her mother suffered from depression and her father was busy with work. Arbus<br />

separated herself from her family and lavish childhood.<br />

At age 18, Diane married her childhood sweetheart who she has dated since 14,<br />

Allan Arbus. She received her first camera from Allan and enrolled in classes with<br />

<strong>photo</strong>grapher, Berenice Abbott. Allan was a <strong>photo</strong>grapher for the US Army Signal<br />

Corps in WWII. While he was stationed during the early 1940s, Diane documented<br />

her first pregnancy which sparked her interest in <strong>photo</strong>graphy. After the war in 1946,<br />

they started a commercial <strong>photo</strong>graphy business called “Diane & Allan Arbus” with<br />

Diane as the art director and Allan as the <strong>photo</strong>grapher. She would come up with<br />

the concepts for their shoots and take care fo the models. Diane eventually grew<br />

dissatisfied with this role, a role that even her husband thought was demeaning. In<br />

1956, Arbus quit the commercial <strong>photo</strong>graphy business. Allan was very supportive of<br />

her, even after she quit commercial <strong>photo</strong>graphy and began developing an independent<br />

relationship to <strong>photo</strong>graphy. They separated in 1959 and got divorced in 1969 but still<br />

remained close because of their daughters. Arbus began a relationship with art director<br />

and painter, Marvin Israel until her death. He was married and made it clear to Arbus<br />

that he was never going to leave his wife but pushed Arbus very hard regarding her work.<br />

He was the one who encouraged her to create her first portfolio.

133<br />

Diane Arbus would wander the streets of New York City with a 35mm Nikon. In 1962, she switched from her camera<br />

which produced grainy, rectangular i<strong>mag</strong>es to a twin-lens reface Rolleiflex camera which produced more detailed<br />

square i<strong>mag</strong>es, on larger 2 1/4 film. She followed strangers and would wait in doorways until she saw someone she<br />

felt compelled to <strong>photo</strong>graph. Arbus began to get more strategic in 1958, plotting in advance the type of people she<br />

wanted to document and numbered her film as she was developing her <strong>photo</strong>s. Her first numbered negative is from<br />

1956 and her last known negative is labeled #7459.<br />

Diane Arbus experienced depressive episodes during her life, similar to those experienced by her mother, which may<br />

have been made worse by symptoms of hepatitis. In 1968, she wrote, “I got up and down a lot,” and her ex-husband<br />

noted that she had “violent changes of mood.” On July 26, 1971, Arbus was living at Westbeth Artists Community in<br />

New York City when she took her own life by ingesting barbiturates and slashing her wrists with a razor. She wrote the<br />

words, “Last Supper” in her diary and placed her appointment book on the stairs leading up to the bathroom. Marvin<br />

Israel found her body in the bathtub two days later. Her ashes were buried at Ferncliff Cemetery but no record exists<br />

at the cemetery. In 1972, a year after she died by suicide, Dian Arbus became the first American <strong>photo</strong>grapher to have<br />

<strong>photo</strong>graphs displayed at the Venice Biennale. Millions traveled to see these exhibitions in 1971-1979.

134<br />

1956<br />

NEW YORK CITY<br />

Woman with Parcels.

1956<br />

NEW YORK CITY<br />

Woman in a Mink Stole and Bow Shoes.<br />

135

136

137<br />

A YOUNG MAN IN CURLERS AT HOME 1966<br />

WEST 20TH STREET, NEW YORK CITY<br />

A close-up shows the man’s pock-marked face with plucked eyebrows, and his hand<br />

with long fingernails holds a cigarette. Early reactions to the <strong>photo</strong>graph were strong;<br />

for example, someone spat on it in 1967 at the Museum of Modern Art.

138<br />

CHILD WITH TOY HAND GRENADE 1962<br />

CENTRAL PARK, NEW YORK CITY<br />

Colin Wood with the left strap of his jumper awkwardly hanging off his shoulder, tensely holds his long, thin arms<br />

by his side. Clenching a toy grenade in his right hand and holding his left hand in a claw-like gesture, his facial<br />

expression is maniacal. However, the contact sheet demonstrates that his deranged appearance was an editorial<br />

choice by Arbus who took a number of shots of this really quite ordinary boy who just shows off for the camera.

139

TEENAGE COUPLE 1963<br />

HUDSON STREET, NEW YORK CITY<br />

Wearing long coats and “worldlywise expressions,”<br />

two adolescents appear older than their ages.<br />

140

141<br />

YOUNG BROOKLYN FAMILY GOING FOR A SUNDAY OUTING 1966<br />

HUDSON STREET, NEW YORK CITY<br />

Richard and Marylin Dauria, who lived in the Bronx. Marylin holds their baby daughter,<br />

and Richard holds the hand of their young son, who is mentally challenged.

TRIPLETS IN THEIR BEDROOM 1963<br />

NEW JERSEY<br />

Three girls sit at the heaad of a bed.

143<br />

1962<br />

CENTRAL PARK, NEW YORK CITY<br />

Two boys smoking.

144<br />

IDENTICAL TWINS 1967<br />

ROSELLE, NEW JERSEY<br />

Young twin sisters Cathleen and Colleen Wade stand side by side in dark dresses. The<br />

uniformity of their clothing and haircut characterize them as being twins while the facial<br />

expressions strongly accentuate their individuality. This <strong>photo</strong>graph is echoed in Stanley<br />

Kubrick’s film, The Shining, which features twins in an identical pose as ghosts.

1965<br />

SANTA MONICA, CALIFORNIA<br />

Mae West in her bedroom.<br />

1967<br />

NEW YORK CITY<br />

Patriotic young man with a flag.

1967<br />

NEW YORK CITY<br />

Boy with a straw hat waiting to march in a Pro-War parade. With<br />

an American flag at his side, he wears a bow tie, a pin in the shape<br />

of a bow tie with an American flag motif, and two round button<br />

badges: “Bomb Hanoi” and “God Bless America / Support Our<br />

Boys in Vietnam”. The i<strong>mag</strong>e may cause the viewer to feel both<br />

different from the boy and sympathetic toward him.<br />

146

147<br />

NAKED MAN BEING A WOMAN 1968<br />

NEW YORK CITY<br />

The subject has been described as in a “Venus-on-the-half-shell pose” or as “a<br />

Madonna turned in contrapposto... with his penis hidden between his legs.” The<br />

parted curtain behind the man adds to the theatrical quality of the <strong>photo</strong>graph.

148<br />

A FAMILY ON THEIR LAWN ONE SUNDAY 1968<br />

WESTCHESTER, NEW YORK<br />

A woman and a man sunbathe while a boy bends over a small plastic wading pool behind them. In 1972, Neil Selkirk was put in charge of producing an exhibition<br />

print of this i<strong>mag</strong>e when Marvin Israel advised him to make the background trees appear “like a theatrical backdrop that might at any moment roll forward<br />

across the lawn.” This anecdote illustrates vividly just how fundamental dialectics between appearance and substance are for the understanding of Arbus’ art.

149

A VERY YOUNG BABY 1968<br />

NEW YORK CITY<br />

A <strong>photo</strong>graph for Harper’s Bazaar depicts Gloria Vanderbilt’s<br />

then-infant son, the future CNN anchorman Anderson Cooper.

151

1970<br />

MARYLAND<br />

152

153

A JEWISH GIANT AT HOME WITH HIS PARENTS 1970<br />

THE BRONX, NEW YORK<br />

Eddie Carmel, the “Jewish Giant,” stands in his family’s apartment with his much shorter mother and father. Arbus<br />

reportedly said to a friend about this picture: “You know how every mother has nightmares when she’s pregnant that<br />

her baby will be born a monster?... I think I got that in the mother’s face....” The <strong>photo</strong>graph motivated Carmel’s<br />

cousin to narrate a 1999 audio documentary about him

155

156<br />

IMOGEN<br />

CUNNINGHAM

157<br />

(APRIL 12, 1883 — JUNE 23, 1976)<br />

Imogene Cunningham was an American <strong>photo</strong>grapher known for her botanical <strong>photo</strong>graphy, nudes, and industrial<br />

landscapes. She was born in Portland, Oregon, the fifth of ten children. She grew up in Seattle, Washington and at<br />

the age of eighteen in 1901, she bought her first camera. A 4x5 inch view camera, inspired by Gertrude Käsebier’s<br />

<strong>photo</strong>graphs. With the help of her chemistry professor, Horace Byers, she began to study the chemistry behind<br />

<strong>photo</strong>graphy and she subsidized her tuition by <strong>photo</strong>graphing plants for the botany department. In 1907, Cunningham<br />

graduated from the University of Washington with a degree in chemistry and her thesis was titles, “Modern Processes<br />

of Photography.” After graduating college, she went to work for Edward S Curtis in his Seattle studio, learning about<br />

the portrait business and practical <strong>photo</strong>graphy. Cunningham learned the technique of platinum printing and became<br />

fascinated by the process. In Seattle, Cunningham opened a studio and won acclaim for portraiture and pictorial work.<br />

Most of her work consisted of sitters in their own homes, in her living room, or in the woods surrounding Cunningham’s<br />

cottage. She became a desired <strong>photo</strong>grapher and exhibited at the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences in 1913.<br />

In 1920, Imogen and her family moved to San Francisco where she refined her style. She took an interest in pattern and<br />

detail, becoming increasingly interested in botanical <strong>photo</strong>graphy, especially flowers. Between 1923 and 1925, she carried<br />

out an in-depth study of the Magnolia flower. Later, she turned her attention to industrial landscapes in Los Angeles and<br />

Oakland. Cunningham changed direction again and became more interested with the human form, particularly hands, and<br />

the hands of artists and musicians. This interest led to her employment by Vanity Fair, <strong>photo</strong>graphing stars without make-up.<br />

As Cunningham moved away from pictorialism and toward sharp-focus <strong>photo</strong>graphy, she joined with like-minded <strong>photo</strong>graphers<br />

to form Group f/64 to promote this style of <strong>photo</strong>graphy. In the 1940s, she turned to documentary street <strong>photo</strong>graphy,<br />

which she executed as a side project while supporting herself with commercial and studio <strong>photo</strong>graphy. Imogen Cunningham<br />

continued to take <strong>photo</strong>s shortly before her death at age 93 in San Francisco, California.

158

159<br />

MILLS COLLEGE AMPHITHEATER 1921<br />

OAKLAND, CALIFORNIA

160<br />

REFUGIO BEACH 1925<br />

GOLETA, CALIFORNIA

MOTHER LODE<br />

URBAN DECONSTRUCTION

OIL TANKS 1940

SHREADED WHEAT TOWER 1928<br />

163

164

SHREADED WHEAT FACTORY 1928<br />

165

ABSTRACT OF CLOUDS

167<br />

CLOUDS 1939<br />

ARIZONA

168<br />

STONEHENGE 1961<br />

WILTSHIRE, ENGLAND

169<br />

WATER TOWER 1961<br />

FINLAND

FAGEOL VENTILATORS 1934

FOREST 1960<br />

FRANCE<br />

171<br />

URBAN DECONSTRUCTION 1956<br />

NEW YORK CITY

172<br />

AGAVE DESIGN 1920

173

174

TWO CALLAS 1925<br />

175

176<br />

CALLA BUD 1929

177

178<br />

COLLETIA CRUCIATA 1929

179

180<br />

STAPELIA 1929

STAPELIA 1928<br />

181

STAPELIA 1928

STAPELIA IN GLASS 1928<br />

183

184

AGAVE 1930<br />

CASKIE’S GARDEN<br />

185

186<br />

AMARYLLIS 1933

187

COLLETIA CRUCIATA DESIGN FOR A SCREEN 1939

ARAUJIA SEED POD 1956<br />

189

ARAUJIA 1953

191

192

HELEN 1928<br />

193

TWO SISTERS 1928

TRIANGLES PLUS ONE 1928<br />

195

196<br />

JOHN BOVINGDON 1929

197

198<br />

MARTHA GRAHAM 1931

199

200<br />

MARTHA GRAHAM 1931

201

202

MARTHA GRAHAM 1931<br />

203

HELENA MEYER 1939<br />

CANYON DE CHELLY, ARIZONA<br />

204

205

206<br />

AFTER THE BATH 1952

DREAM WALKING 1968<br />

207

208

IRENE ’BOBBIE’ LIBARRY 1976<br />

209

FRIDA KAHLO RIVERA 1931<br />

Painter and wife of Diego Rivera<br />

210

211

212<br />

FRIDA KAHLO RIVERA 1931

213

214<br />

BLIND SCULPTOR 1952

215

216

RUTH ASAWA WORKING ON A WIRE SCULPTURE 1952<br />

217

RUTH ASAWA 1952<br />

Ruth Asawa holding a form within a form sculpture. A looped wire sculpture.<br />

218

RUTH ASAWA 1957<br />

219

RUTH ASAWA 1957

RUTH ASAWA AND HER CHILDREN 1957<br />

221

222<br />

RUTH ASAWA 1973

WIRE SCULPTURE AND SHADOWS<br />

223

TYPE NOTE<br />

THE TEXT OF THIS BOOK IS SET IN BRANDON GROTESQUE.<br />

THE HEADER TEXT IS SET IN HOEFLER’S DIDOT IN L96 LIGHT.<br />

THIS BOOK WAS DESIGNED BY HANNA KIM

226