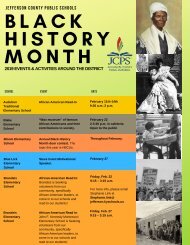

Envision Equity February 2019 Special Black History Month Edition

Envision Equity February 2019 Special Black History Month Edition

Envision Equity February 2019 Special Black History Month Edition

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

ENVISION<br />

<br />

EQUITY<br />

HARLEM<br />

RENAISSANCE<br />

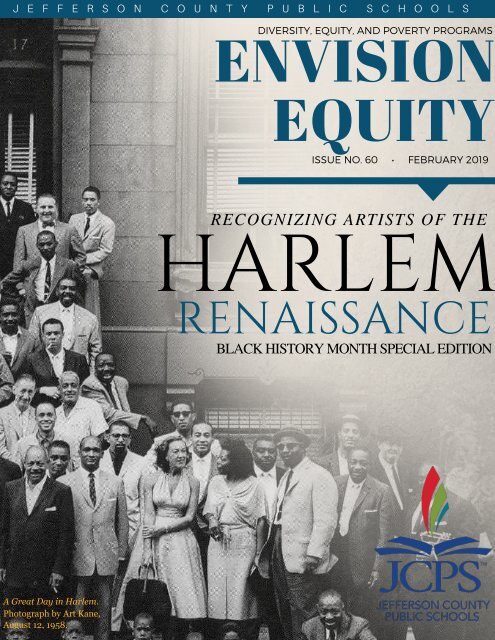

A Great Day in Harlem.<br />

Photograph by Art Kane,<br />

August 12, 1958.<br />

Photo, google images.

<strong>Envision</strong> <strong>Equity</strong> <strong>February</strong> <strong>2019</strong><br />

THE PILLARS OF THE<br />

<br />

HARLEM RENAISSANCE<br />

ARE WHAT THE THREE<br />

PILLARS ARE ABOUT!<br />

By John D. Marshall—Ed.D. Chief <strong>Equity</strong> Officer, Jefferson County Public Schools<br />

Dr. John Marshall<br />

I am thanking in advance the teachers, principals, and others<br />

who take well-invested time to teach a fuller curriculum that<br />

includes a more complete picture of the world and America.<br />

This special edition of <strong>Envision</strong> <strong>Equity</strong> pays homage to the<br />

artists of the Harlem Renaissance. These artists capture(d) the<br />

beauty, pain, love, mistreatment, and genius of <strong>Black</strong><br />

(American) life. Whether it be through song, sculpture, acting,<br />

writing, etc., these <strong>Black</strong> artists created memorable monuments<br />

and moments that deserve far more credit and attention than<br />

many of them receive.<br />

Coined the father of education, Carter G. Woodson said, “If a race<br />

has no history, if it has no worthwhile tradition, it becomes a<br />

negligible factor in the thought of the world, and it stands in<br />

danger of being exterminated.” I, for one, wholeheartedly agree<br />

with that statement. What people become is due in some part to<br />

what they know and or do not know. When a person does not know<br />

nor is shown the abundance of attributions, contributions, and<br />

institutions created, owned, and led by his or her culture, it is no<br />

surprise that in some cases he or she (un)consciously acquiesces to<br />

the saturation of a selected<br />

education that does not<br />

wholly, if at all, teach or reach<br />

the heart of the child.<br />

Mr. Woodson also said, “The mere imparting of information is<br />

not education.” Again true! Long gone (should be) are the days Dr. Carter G. Woodson<br />

of lecture, list, listen, repeat. The three Jefferson County Public School (JCPS) initiatives—called the<br />

three pillars: Backpack of Success Skills, Racial <strong>Equity</strong>, and Culture and Climate—should and could<br />

usher in a new way of not just learning but also being. We are poised to position Henry O. Tanner to<br />

abut a white artist who receives more attention only due to curricula selection. We can share the grit

<strong>Envision</strong> <strong>Equity</strong> <strong>February</strong> <strong>2019</strong><br />

and grace found in Aaron<br />

Douglas's art and<br />

unapologetically use those<br />

paintings to show future<br />

leaders the systemic<br />

failures, successes, and<br />

hope of a world and<br />

country. The artful teacher<br />

can now challenge students<br />

to dive further into said art<br />

and discuss, demonstrate,<br />

debate, doodle, etc., his or<br />

her own feelings and<br />

opinion about the work.<br />

That doodle, essay, or entry<br />

could morph into a student<br />

defense that elucidates her<br />

or his understanding of self<br />

and the society in which he or she lives. This is also way to pay homage to Harlemites who deserve<br />

more worldly attention than he or she receives now. There is no Misty Copeland without Josephine<br />

Baker. There is no Alicia Keys without Florence Mills. There is no Chadwick Boseman without Paul<br />

Robeson. The opportunity, although long overdue, is now. Now we can/must bring in artful, heartful,<br />

and fearless teaching that removes the holey curriculum and ushers in a system that marries deeper<br />

learning and racial equity, which in turn evokes a culture and climate conducive for “Harlem” and the<br />

minds that need to know about the geniuses who worked, played, and lived there.<br />

This special edition of <strong>Envision</strong> <strong>Equity</strong> is an attempt to respect more than the month and the<br />

historical greatness of the brilliant, brave, beautiful <strong>Black</strong> artists gracing these pages, but to also<br />

celebrate the artistry of teachers and leaders who know and show students that without Harlem<br />

(<strong>Black</strong>) history, there is no accurate American history.<br />

“Those who have no record of what their forebears have accomplished lose the inspiration which<br />

comes from the teaching of biography and history.”<br />

—Carter G. Woodson

<strong>Envision</strong> <strong>Equity</strong> <strong>February</strong> <strong>2019</strong><br />

Introduction<br />

<br />

With the end of the Civil War in 1865, hundreds of<br />

thousands of African Americans newly freed from the<br />

yoke of slavery in the South began to dream of fuller<br />

participation in American society, including political<br />

empowerment, equal economic opportunity, and<br />

economic and cultural self-determination.<br />

With booming economies across the North and Midwest<br />

offering industrial jobs for workers of every race, many<br />

African Americans realized their hopes for a better<br />

standard of living—and a more racially tolerant<br />

environment—lay outside the South. By the turn of the<br />

20th century, the Great Migration was underway as<br />

hundreds of thousands of African Americans relocated<br />

to cities like Chicago, Los Angeles, Detroit, Philadelphia, and New York. The Harlem section of<br />

Manhattan, which covers just three square miles, drew nearly 175,000 African Americans, giving the<br />

neighborhood the largest concentration of black people in the world. Harlem became a destination for<br />

African Americans of all backgrounds. From unskilled laborers to an educated middle-class, they<br />

shared common experiences of slavery, emancipation, and racial oppression, as well as a determination<br />

to forge a new identity as free people.<br />

The Great Migration drew to Harlem some of the greatest minds and brightest talents of the day, an<br />

astonishing array of African American artists and scholars. Between the end of World War I and the<br />

mid-1930s, they produced one of the most significant eras of cultural expression in the nation’s history<br />

—the Harlem Renaissance. Yet this cultural explosion also occurred in Cleveland, Los Angeles and<br />

many cities shaped by the great migration. Alain Locke, a Harvard-educated writer, critic, and teacher<br />

who became known as the “dean” of the Harlem Renaissance, described it as a “spiritual coming of age”<br />

in which African Americans transformed “social disillusionment to race pride.”<br />

The Harlem Renaissance encompassed poetry and prose, painting and sculpture, jazz and swing, opera<br />

and dance. What united these diverse art forms was their realistic presentation of what it meant to be<br />

black in America, what writer Langston Hughes called an “expression of our individual dark-skinned<br />

selves,” as well as a new militancy in asserting their civil and political rights.<br />

Among the Renaissance’s most significant contributors were electrifying performers Josephine Baker<br />

and Paul Robeson; writers and poets Zora Neale Hurston, Effie Lee Newsome, Countee Cullen; visual<br />

artists Aaron Douglas and Augusta Savage; and an extraordinary list of legendary musicians, including<br />

Louis Armstrong, Count Basie, Eubie Blake, Cab Calloway, Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday, Ivie<br />

Anderson, Josephine Baker, Fats Waller, Jelly Roll Morton, and countless others.<br />

Please enjoy these profiles of notable members of the Harlem Renaissance era. A lesson plan is<br />

included on pages 35 & 36 for teachers to use in the classroom.

<strong>Envision</strong> <strong>Equity</strong> <strong>February</strong> <strong>2019</strong><br />

Aaron Douglas<br />

<br />

<br />

Born in Topeka, Kansas, Aaron Douglas was a leading figure in the artistic and literary movement known as the<br />

Harlem Renaissance. He is sometimes referred to as "the father of black American art." Douglas developed an<br />

interest in art early on, finding some of his inspiration from his mother's love for painting watercolors.<br />

After graduating from Topeka High School in 1917, Douglas attended the University of Nebraska, Lincoln. There,<br />

he pursued his passion for creating art, earning a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in 1922. Around that time, he<br />

shared his interest with the students of Lincoln High School in Kansas City, Missouri. He taught there for two<br />

years, before deciding to move to New York City. At the time, New York's Harlem neighborhood had a thriving<br />

arts scene.<br />

Arriving in 1925, Douglas quickly became immersed Harlem's cultural life.<br />

He contributed illustrations to Opportunity, the National Urban League's<br />

magazine, and to The Crisis, put out by the National Association for the<br />

Advancement Colored People. Douglas created powerful images of<br />

African-American life and struggles, and won awards for the work he<br />

created for these publications, ultimately receiving a commission to<br />

illustrate an anthology of philosopher Alain LeRoy Locke's work,<br />

entitled The New Negro.<br />

Douglas had a unique artistic style that fused his interests in<br />

modernism and African art. A student of German-born painter<br />

Winold Reiss, he incorporated parts of Art Deco along with<br />

elements of Egyptian wall paintings in his work. Many of his<br />

figures appeared as bold silhouettes.<br />

In 1926, Douglas married teacher Alta Sawyer, and the couple's<br />

Harlem home became a social Mecca for the likes of Langston<br />

Hughes and W. E. B. Du Bois, among other powerful African<br />

Americans of the early 1900s. Around the same time, Douglas<br />

worked on a magazine with novelist Wallace Thurman to feature<br />

African-American art and literature. Entitled Fire!!, the magazine<br />

only published one issue.<br />

Aaron Douglas. Aspects of Negro Life: The<br />

Negro in an African Setting. Oil on canvas,<br />

1934. The New York Public Library,<br />

Schomburg Center for Research in <strong>Black</strong><br />

Culture, Art and Artifacts Division.

<strong>Envision</strong> <strong>Equity</strong> <strong>February</strong> <strong>2019</strong><br />

Why I<br />

Teaching Art<br />

<br />

<br />

“Maybe you should be an art teacher,” was a statement my group chaperone uttered to me<br />

during an Art Department field trip to New York City during my senior year of high school. In<br />

an effort to add confusion to what seemed, at that point, a life-altering decision, the idea<br />

echoed in my mind. At that time, my love for art resonated in the fact that I was good at it. I<br />

would graffiti the cover of every folder, doodle on every notebook cover, and scribble random<br />

thoughts on the edge of every single paper I touched.<br />

In learning effective and impactful teaching strategies, my theory is that art is a learned<br />

subject,<br />

just as reading and math are. The more effort, focus, and hard work<br />

placed into the subject, the higher the outcome for successfully<br />

learned skills. Beautiful moments arise when students who<br />

witness themselves struggling in core subjects find success<br />

stemming from their natural art skills and capability to<br />

express themselves through forms not related to their math<br />

facts or reading levels. The ultimate payoff as an art<br />

teacher is to see the pride of completing a masterpiece<br />

from students who often thought positive outcomes<br />

were void in their lives; the picture they paint is<br />

priceless.<br />

Photos, Abdul Sharif

<strong>Envision</strong> <strong>Equity</strong> <strong>February</strong> <strong>2019</strong><br />

Duke Ellington<br />

<br />

<br />

Born on April 29, 1899, Duke Ellington was raised by two talented, musical parents in a middle-class<br />

neighborhood of Washington D.C. At the age of seven, he began studying piano and earned the nickname<br />

"Duke" for his gentlemanly ways. Inspired by his job as a soda jerk, he wrote his first composition, "Soda<br />

Fountain Rag," at the age of 15. Despite being awarded an art scholarship to the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New<br />

York, Ellington followed his passion for ragtime and began to play professionally at age 17.<br />

In the 1920s, Ellington performed in Broadway nightclubs as the bandleader of a sextet, a<br />

which in time grew to a 10-piece ensemble. Ellington sought out musicians with unique<br />

playing styles, such as Bubber Miley, who used a plunger to make the "wa-wa" sound,<br />

and Joe Nanton, who gave the world his trombone "growl." At various times, his<br />

ensemble included the trumpeter Cootie Williams, cornetist Rex Stewart and alto<br />

saxophonist Johnny Hodges. Ellington made hundreds of recordings with his<br />

bands, appeared in films and on radio, and toured Europe on two occasions in the<br />

1930s.<br />

Ellington's fame rose to the rafters in the 1940s when he composed several<br />

masterworks, including "Concerto for Cootie," "Cotton Tail" and "Ko-Ko." Some of<br />

his most popular songs included "It Don't Mean a Thing if It Ain't Got That Swing,"<br />

"Sophisticated Lady," "Prelude to a Kiss," "Solitude," and "Satin Doll." A number of<br />

his hits were sung by the impressive Ivie Anderson, a favorite female vocalist of<br />

Duke's band.<br />

group

Finish The Statement<br />

<br />

If I could spend one day in Harlem, New York during the<br />

Harlem Renaissance, I would...<br />

“I would sit in on a set with<br />

Duke Ellington at the<br />

Cotton Club while he<br />

played all of his big band<br />

hits.”<br />

John D. Marshall Ed.D<br />

Chief <strong>Equity</strong> Officer<br />

“Mine would have to be the<br />

chance to hear Louis<br />

Armstrong live. I can<br />

remember hearing him on<br />

TV (it may have been about<br />

the time of his death) and<br />

asking my dad who he was<br />

and what instrument he was<br />

playing.”<br />

Jimmy Adams<br />

Chief of Human Resources<br />

“I would hang out with<br />

Zora Neale Hurston. I’d<br />

ask her to read her<br />

writings aloud and to<br />

discuss her research.<br />

Most importantly, I’d<br />

encourage her and tell<br />

her how amazing<br />

people (including me)<br />

would think her work<br />

was in the future.”<br />

Kim Morales, Principal<br />

Seneca High School<br />

“Sit down, relax, and<br />

enjoy the amazing jazz<br />

music.”<br />

Randy Frantz<br />

JCPS Director of<br />

Transportation<br />

“I would spend the day talking to Langston Hughes about his personal and<br />

cultural experiences, and how those experiences influenced his poetic<br />

revelations and artistry of black life during the Renaissance.”<br />

Dr. Toetta Taul<br />

Marion C. Moore<br />

Freshman Academy Principal

<strong>Envision</strong> <strong>Equity</strong> <strong>February</strong> <strong>2019</strong><br />

William Henry Johnson<br />

<br />

<br />

Artist William Henry Johnson was born on March 18, 1901, in the small town of Florence, South Carolina, to<br />

parents Henry Johnson and Alice Smoot, who were both laborers. Johnson realized his dreams of becoming<br />

an artist at a young age, copying cartoons from the paper as a child. However, as the oldest of the family's five<br />

children, who lived in a poor, segregated town in the South, Johnson tucked away his aspirations of becoming<br />

an artist, deeming them unrealistic.<br />

But Johnson finally left South Carolina in 1918, at the age of 17, to pursue his dreams in New York City. There,<br />

he enrolled at the National Academy of Design and met Charles Webster Hawthorne, a well-known artist who<br />

took Johnson under his wing. While Hawthorne recognized Johnson's talent, he knew that Johnson would<br />

have a difficult time excelling as an African-American artist in the United States, and thus raised enough<br />

money to send the young artist to Paris, France, upon his graduation in 1926.<br />

Though they had moved to avoid any conflict with the Nazis, William and Holcha still faced racism and<br />

discrimination as an interracial couple living in the United States. The artistic community of Harlem, New<br />

York, which had become more enlightened and experimental following the Harlem Renaissance, embraced the<br />

couple, however.<br />

Around this time, Johnson took a job as an art teacher at the Harlem Community<br />

also continuing to create art in his spare time. Transitioning from<br />

expressionism to a primitive style of artwork, or primitivism,<br />

Johnson's work during this time displayed brighter colors and twodimensional<br />

objects, and often included portrayals of African-<br />

American life in Harlem, the South and the military. Some of these<br />

works, including paintings depicting black soldiers fighting on the<br />

front lines as well as the segregation that took place there, served<br />

as commentaries on the treatment of African Americans in the<br />

U.S. Army during World War II.<br />

Art Center,<br />

William H. Johnson, Jitterbugs (II), ca. 1941,<br />

oil on paperboard.

<strong>Envision</strong> <strong>Equity</strong> <strong>February</strong> <strong>2019</strong><br />

A Day in Harlem with<br />

Mr. Ashford<br />

<br />

<br />

If I could spend one day in Harlem, New York, during the Harlem Renaissance, I would shed<br />

my denim jeans, like the other migrants from the South, for a three-piece suit and fedora. I<br />

would proudly walk two square miles around this oasis of black consciousness before<br />

marching with protesters at the Silence Parade. I would then press my way through the<br />

thousands of participants organized to protest violent crimes against African Americans,<br />

until I was right behind James Weldon Johnson and W.E.B. DuBois. I would tell W.E.B.<br />

DuBois how The Souls of <strong>Black</strong> Folks changed my perspective and ask him to be my tour<br />

guide in hopes he would take me to Negrotti Manor on 136th Street, by way<br />

of his favorite soul food restaurant. I would ask DuBois his opinion of<br />

Alain Locke, “The New Negro,” and the art of Erin Douglas inspired<br />

by Marcus Garvey’s vision of the motherland. I would ask DuBois<br />

how he felt the first time he heard a Langston Hughes poem. I<br />

would buy us both tickets to the theater to see movies starring<br />

actors, who looked like us, acting out scripts that unapologetically<br />

explored the racial challenges and issues of black community from<br />

the black perspective. As evening neared, I would tip-toe in the back<br />

door of the Cotton Club to observe the mixed crowd and witness jazz<br />

in its purest form conducted by no other than Duke Ellington himself.<br />

But those who truly know me know, I’m not a “Bourgeois Negro,” so, I<br />

would have to top off my night with a trip to the nearest<br />

speakeasy. Where I could hopefully hear some blues, sip on<br />

some hooch or giggle water, and sweat out my zoot suit<br />

dancing with a tall chocolate drink of water.<br />

Photos, Abdul Sharif

<strong>Envision</strong> <strong>Equity</strong> <strong>February</strong> <strong>2019</strong><br />

Augusta Savage<br />

<br />

<br />

Augusta Savage was born Augusta Christine Fells on <strong>February</strong> 29, 1892, in Green Cove Springs, Florida. Part of a<br />

large family, she began making art as a child, using the natural clay found in her area. Skipping school at times,<br />

she enjoyed sculpting animals and other small figures. But her father, a Methodist minister, didn't approve of<br />

this activity and did whatever he could to stop her. Savage once said that her father "almost whipped all the art<br />

out of me."<br />

Despite her father's objections, Savage continued to make sculptures. When the family moved to West Palm<br />

Beach, Florida, in 1915, she encountered a new challenge: a lack of clay. Savage eventually got some materials<br />

from a local potter and created a group of figures that she entered in a local county fair. Her work was well<br />

received, winning a prize and along the way the support of the fair's superintendent, George Graham Currie. He<br />

encouraged her to study art despite the racism of the day.<br />

Savage<br />

time<br />

of<br />

soon started to make a name for herself as a portrait sculptor. Her works from this<br />

include busts of such prominent African Americans as W. E. B. Du<br />

Bois and Marcus Garvey. Savage was considered to be one of the leading artists<br />

the Harlem Renaissance, a preeminent African-American literary and artistic<br />

movement of the 1920s and '30s.<br />

Eventually, following a series of family crises, Savage got her opportunity to<br />

study abroad. She was awarded a Julius Rosenwald fellowship in 1929, based<br />

in part on a bust of her nephew entitled Gamin. Savage spent time in Paris,<br />

where she exhibited her work at the Grand Palais. She earned a<br />

second Rosenwald fellowship to continue her studies for another year, and a<br />

separate Carnegie Foundation grant<br />

allowed her<br />

to travel to other European countries.

<strong>Envision</strong> <strong>Equity</strong> <strong>February</strong> <strong>2019</strong><br />

Billie Holiday<br />

<br />

<br />

Billie Holiday was born Eleanora Fagan on April 7, 1915, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (Some sources say her<br />

birthplace was Baltimore, Maryland, and her birth certificate reportedly reads "Elinore Harris.")<br />

Holiday spent much of her childhood in Baltimore. Her mother, Sadie, was only a teenager when she had her.<br />

Her father is widely believed to be Clarence Holiday, who eventually became a successful jazz musician,<br />

playing with the likes of Fletcher Henderson.<br />

In her difficult early life, Holiday found solace in music, singing along to the records<br />

of Bessie Smith and Louis Armstrong. She followed her mother, who had moved to<br />

New York City in the late 1920s, and worked in a house of prostitution in<br />

Harlem for a time.<br />

Around 1930, Holiday began singing in local clubs and renamed<br />

herself "Billie" after the film star Billie Dove.<br />

Holiday toured with the Count Basie Orchestra in 1937. The following<br />

year, she worked withArtie Shaw and his orchestra. Holiday broke new<br />

ground with Shaw, becoming one of the first female African American<br />

vocalists to work with a white orchestra.<br />

Promoters, however, objected to Holiday—for her race and for her unique<br />

vocal style—and she ended up leaving the orchestra out of frustration.<br />

While her hard living was taking a toll on her voice, Holiday continued to<br />

tour and record in the 1950s. She began recording for Norman<br />

Granz, the owner of several small jazz labels, in 1952. Two<br />

years later, Holiday had a hugely successful tour of Europe.<br />

Holiday also caught the public's attention by sharing her life<br />

story with the world in 1956. Her autobiography, Lady Sings<br />

the Blues (1956), was written in collaboration by William Dufty.

<strong>Envision</strong> <strong>Equity</strong> <strong>February</strong> <strong>2019</strong><br />

Romare Bearden<br />

<br />

<br />

An only child, Romare Bearden was born on September 2, 1914, in Charlotte, North Carolina. When he was still a<br />

child, the family moved to Harlem, New York City, where his mother was a well-known journalist and political<br />

activist. He received a bachelor of science degree from New York University because, he said, "I thought I wanted<br />

to be a medical doctor." E. Simms Campbell, the renowned African American cartoonist, encouraged him to<br />

study painting with George Grosz, the German-born painter and satirical draftsman, at the Art Students' League<br />

in New York. "It was Grosz, " Bearden remembered with gratitude, "who first introduced me to classical<br />

draftsmen like Hogarth and Ingres." Essential as formal institutions were to his development as a person and an<br />

artist, his association with African American artists and intellectuals of the Depression period cannot be<br />

minimized. Among these were the painters Norman Lewis and Jacob Lawrence and the writer Ralph Ellison,<br />

who maintained an atmosphere of social and political concern which heavily influenced Bearden's early work.<br />

Even though his concern for these problems in no way diminished later and all his works abound in ethnic<br />

subject matter, the mild-mannered, almost shy artist insisted that he was not a social propagandist. "My subject<br />

is people, " he said. "They just happen to turn out to be Negro.”<br />

Early in his career he emulated the styles of Rufino Tamayo and José Clemente Orozco, painting simple forms<br />

and echoing the crude power he had come to admire in medieval art. His paintings of everyday black life were<br />

forceful in color; the figures followed simple patterns and their statements were literal, as in graphic art rather<br />

than painting. By 1945 he had begun to adopt a less literal, more personal style, which<br />

proved<br />

to be the most congenial for his unique artistic expressions. In the 1950s, while working as<br />

a New<br />

York City Welfare Department investigator, he expressed his feelings in lyrical<br />

abstractions.<br />

The early 1960s brought a period of transition for Bearden. In 1963 a group of African<br />

American artists began meeting in his Harlem studio. Calling themselves the Spiral<br />

Group, they sought to define their roles as black artists within the context of the<br />

growing civil rights movement.<br />

His "Projections" series, exhibited in 1964, caused a wave of controversy<br />

and excitement. The tormented faces of African American women<br />

hanging upside down on the cracked stoops of Harlem tenements, New<br />

York bridges soaring out of Carolina cotton fields, and African<br />

pyramids colliding with American folk singers strumming guitars<br />

prompted one critic to write that the show comprised "a collection of<br />

headhunters." These startling images, constructed from newspaper<br />

and magazine photographs, had been enlarged from their original<br />

color into huge black-and-white photographs that provided the<br />

artist's desired effect of urgency.<br />

Mr. Jeremiah's Sunset Guitar, 1981.

<strong>Envision</strong> <strong>Equity</strong> <strong>February</strong> <strong>2019</strong><br />

Bill “Bojangles” Robinson<br />

<br />

<br />

Bill "Bojangles" Robinson was born Luther Robinson in Richmond, Virginia, on May 25, 1878. His father,<br />

Maxwell, worked in a machine shop, while his mother, Maria, was a choir singer. After both of his parents died<br />

in 1885, Robinson was raised by his grandmother, Bedilia, who had been a slave earlier in her life. According to<br />

Robinson, he used physical force to compel his brother, Bill, to switch names with him, since he did not care for<br />

his given name of Luther. Additionally, as a young man, he earned the nickname "Bojangles" for his contentious<br />

tendencies.<br />

At the age of 5, Robinson began dancing for a living, performing in local beer gardens. In 1886, at the age of 9,<br />

he joined Mayme Remington's touring troupe. In 1891, he joined a traveling company, later performing as a<br />

vaudeville act. He achieved great success as a nightclub and musical-comedy performer. At this stage of<br />

his career, he performed almost exclusively in black theaters before<br />

black audiences.<br />

Robinson's fame withstood the decline of African-American revues. He starred in 14<br />

Hollywood motion pictures, many of them musicals, and played<br />

multiple roles<br />

opposite the child star Shirley Temple. His film credits<br />

include Rebecca of<br />

Sunnybrook Farm, The Little Colonel and Stormy<br />

Weather, costarring<br />

Lena Horne and Cab Calloway. Despite<br />

his fame,<br />

Robinson was not able to transcend the<br />

narrow range of<br />

stereotypical roles written for black<br />

actors at the time. By<br />

accepting these roles, Robinson<br />

was able to maintain steady<br />

employment and remain in<br />

the public eye. In 1939, at the<br />

age of 61, he performed<br />

in The Hot Mikado, a jazz-inspired<br />

interpretation of<br />

Gilbert and Sullivan's operetta.<br />

Robinson<br />

celebrated his 61st birthday publicly<br />

by dancing down 61<br />

blocks of Broadway.

Finish The Statement<br />

<br />

If I could spend one day in Harlem, New York during the<br />

Harlem Renaissance, I would...<br />

“Start the day with a plate of chicken and waffles (the dish<br />

originated in Harlem), spend the day walking around soaking up<br />

the art, culture and camaraderie, then end the day at the Cotton<br />

Club enjoying the best of the best of Jazz.”<br />

Ben Johnson, CPRP<br />

Assistant Director, Recreation<br />

Louisville Parks and Recreation<br />

“If I could spend one day in Harlem New York during the<br />

Harlem Renaissance, I would speak with community leaders &<br />

owners of black businesses to learn how community campaigns<br />

during that time promoted the concept of the 'Double Duty<br />

Dollar' and encouraged residents to shop in black<br />

establishments. Then I would visit the Cotton Club! Hopefully,<br />

Duke Ellington would be performing!”<br />

Sam Johnson<br />

Director of Youth Development and Education<br />

Louisville Urban League, Inc.<br />

“If I could spend one day in Harlem New York during the<br />

Harlem Renaissance, I would meet up with Zora Neal<br />

Hurston and talk about her writings.”<br />

Kellie Watson<br />

Chief <strong>Equity</strong> Officer <br />

at Louisville Metro Government

<strong>Envision</strong> <strong>Equity</strong> <strong>February</strong> <strong>2019</strong><br />

Alain Locke<br />

<br />

<br />

Alain LeRoy Locke was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on September 13, 1886, to father Pliny Ishmael and<br />

mother Mary Hawkins Locke. A gifted student, Locke graduated from Philadelphia's Central High School second<br />

in his class in 1902. He attended the Philadelphia School of Pedagogy before matriculating at Harvard<br />

University, from which he graduated in 1907 with degrees in both literature and philosophy.<br />

Despite his intellect and clear talent, Locke faced significant barriers as an African American. Though he was<br />

selected as the first African-American Rhodes Scholar, Locke was denied admission to several colleges at the<br />

University of Oxford because of his race. He finally gained entry into Hertford College, where he studied from<br />

1907 to 1910. Locke also studied philosophy at the University of Berlin during his years abroad.<br />

Locke promoted African-American artists and writers, encouraging them to look to Africa for artistic inspiration.<br />

Author Zora Neale Hurston received significant support from Locke. He also reviewed the work of African-<br />

American scholars in the pages of the periodicals Opportunity and Phylon, and published work on African-<br />

American art, theater, poetry and music.<br />

Much of Locke's writing focused on African and African-American identity. His collection of writing and<br />

illustrations, The New Negro, was published in 1925 and quickly became a classic. He also published pieces on<br />

the Harlem Renaissance, communicating the energy and potential of Harlem culture to a wide audience of both<br />

black and white readers. For his part in developing the movement, Locke has been dubbed the "Father of the<br />

Harlem Renaissance." His views on African-American intellectual and cultural life differed sharply from those of<br />

other Harlem Renaissance leaders, however, including W.E.B. Du Bois (who was also a friend of Locke's). While<br />

Du Bois believed that African-American artists should aim to uplift their race, Locke argued that the artist's<br />

responsibility was primarily to himself or herself.

<strong>Envision</strong> <strong>Equity</strong> <strong>February</strong> <strong>2019</strong><br />

Cab Calloway<br />

<br />

<br />

Singer and bandleader Cab Calloway was born in Rochester, New York, in 1907. He learned the art of scat<br />

singing before landing a regular gig at Harlem's famous Cotton Club. Following the enormous success of his<br />

song "Minnie the Moocher" (1931), Calloway became one of the most popular entertainers of the 1930s and '40s.<br />

He appeared on stage and in films before his death in 1994, at age 86, in Hockessin, Delaware.<br />

In 1930, Calloway got a gig at Harlem's famed Cotton Club. Soon, as the bandleader of Cab Calloway and his<br />

Orchestra, he became a regular performer at the popular nightspot. Calloway hit the big time with "Minnie the<br />

Moocher" (1931), a No. 1 song that sold more than one million copies. The tune's famous call-and-response "hide-hi-de-ho"<br />

chorus—improvised when he couldn't recall a lyric—became Calloway's signature phrase for the<br />

rest of his career.<br />

Calloway and his orchestra had successful tours in Canada, Europe and across the United States, traveling in<br />

private train cars when they visited the South in order to escape some of the hardships of segregation. With his<br />

enticing voice, energetic onstage moves and dapper white tuxedos, Calloway was the star attraction. However,<br />

the group's musical talent was just as impressive, partly because the salaries Calloway offered were<br />

second only to Duke Ellington's. The standout musicians Calloway performed with<br />

include<br />

saxophonist Chu Berry, trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie and drummer Cozy Cole.<br />

In 1993, President Bill Clinton presented Calloway with a National Medal of<br />

Arts. Calloway's later years were spent in White Plains, New York, until he<br />

had a stroke in June 1994. He then moved to a nursing home in Hockessin,<br />

Delaware, where he died on November 18, 1994, at the age of 86.<br />

the

<strong>Envision</strong> <strong>Equity</strong> <strong>February</strong> <strong>2019</strong><br />

Ella Fitzgerald<br />

<br />

<br />

Born in 1917, Ella Fitzgerald turned to singing after a troubled childhood and debuted at the Apollo Theater in<br />

1934. Discovered in an amateur contest, she went on to become the top female jazz singer for decades.<br />

In 1958, Fitzgerald made history as the first African-American woman to win a Grammy Award. Due in no small<br />

part to her vocal quality, with lucid intonation and a broad range, the singer would go on to win 13 Grammys in<br />

total and sell more than 40 million albums.<br />

Her multi-volume "songbooks" on Verve Records are among America's recording treasures. Fitzgerald died in<br />

California in 1996.<br />

In the mid-1940s, Granz had started Jazz at the Philharmonic, a series of concerts and live records featuring<br />

most of the genre's great performers. Fitzgerald also hired Granz to become her manager.<br />

Around this time, Fitzgerald went on tour with Dizzy Gillespie and his band. She started changing her singing<br />

style, incorporating scat singing during her performances.<br />

Fitzgerald also fell in love with Gillespie's bass player Ray Brown. The pair wed in 1947, and they adopted a child<br />

born to Fitzgerald's half-sister whom they named Raymond "Ray" Brown Jr. The marriage ended in 1952.<br />

In 1956, Fitzgerald began recording for the newly created Verve. She made<br />

most popular albums for the label, starting out with 1956's Ella<br />

Sings the Cole PorterSong Book.<br />

At the very first Grammy Awards in 1958, Fitzgerald picked up her<br />

Grammys—and made history as the first African-American woman to<br />

award—for best individual jazz performance and best female vocal<br />

performance for the two songbook projects Ella Fitzgerald Sings<br />

Ellington Song Book and Ella Fitzgerald Sings the Irving Berlin Song<br />

Book, respectively. (She worked directly with Ellington on the former<br />

some of her<br />

Fitzgerald<br />

first two<br />

win the<br />

the Duke<br />

album.)

<strong>Envision</strong> <strong>Equity</strong> <strong>February</strong> <strong>2019</strong><br />

Jacob Lawrence<br />

<br />

<br />

Raised in Harlem, New York, Jacob Lawrence became the most renowned African-<br />

American artist of his time. Known for producing narrative collections like<br />

the Migration Series and War Series, he illustrated the African-American experience<br />

using vivid colors set against black and brown figures. He also served as a professor of<br />

art at the University of Washington for 15 years.<br />

At the outbreak of World War II, Lawrence was drafted into the United States Coast<br />

Guard. After being briefly stationed in Florida and Massachusetts, he was assigned to be<br />

the Coast Guard artist aboard a troopship, documenting the war experience as he traveled<br />

around the world. During this time, he produced close to 50<br />

paintings but all ended up being lost.<br />

When his tour of duty ended, Lawrence received a Guggenheim<br />

Fellowship and painted his War Series. He was also invited by Josef<br />

Albers to teach the summer session at <strong>Black</strong> Mountain College in North<br />

Carolina. Albers reportedly hired a private train car to transport Lawrence<br />

and his wife to the college so they wouldn’t be forced to transfer to the “colored”<br />

car when the train crossed the Mason-Dixon Line.<br />

When he returned to New York, Lawrence continued honing his craft but began<br />

struggling with depression. In 1949 he admitted himself into Hillside Hospital in<br />

Queens, staying for close to a year. As a patient at the facility, he produced artwork that<br />

reflected his emotional state, incorporating subdued colors and melancholy figures in his<br />

paintings, which was a sharp contrast to his other works.<br />

In 1951, Lawrence painted works based on memories of performances at the Apollo<br />

Theater in Harlem. He also began teaching again, first at Pratt Institute and later the<br />

New School for Social Research and the Art Students League.<br />

Jacob Lawrence In the North the Negro had better educational facilities 1940-41

<strong>Envision</strong> <strong>Equity</strong> <strong>February</strong> <strong>2019</strong><br />

James Van Der Zee<br />

<br />

<br />

The Harlem Renaissance was in full swing during the 1920s and '30s, and for decades, Van Der Zee would<br />

photograph Harlemites of all backgrounds and occupations, though his work is particularly noted for its<br />

pioneering depiction of middle-class African-American life. He took thousands<br />

of pictures, mostly<br />

indoor portraits, and labeled each of his photos with a signature and date,<br />

which would<br />

prove to be important for future documentation.<br />

Although Van Der Zee photographed many African-American<br />

including Florence Mills, Hazel Scott and Adam Clayton Powell Jr.—<br />

his work was of the straightforward commercial studio variety:<br />

weddings and funerals (including pictures of the dead for grieving<br />

families), family groups, teams, lodges, clubs, and people simply<br />

to have a record of themselves in fine clothes. He often<br />

supplied props or costumes and took time to carefully pose<br />

subjects, giving the picture an accessible narrative.<br />

Van Der Zee's photos sometimes contained special<br />

from the result of darkroom manipulation. In one<br />

image, a 1920 photograph titled "Future Expectations<br />

(Wedding Day)," a young couple is presented in bride<br />

and groom finery, with a ghostly, transparent image of<br />

a child at their feet.<br />

With the advent of personal cameras in the middle of<br />

the century, the desire for Van Der Zee's services<br />

dwindled; he procured less and less commissions,<br />

though he maintained an alternative business in<br />

image restoration and mail order sales. He and<br />

Greenlee were of very limited means when, in 1969, the<br />

Metropolitan Museum of Art mounted an exhibition<br />

featuring Van Der Zee, Harlem on My Mind, bringing the<br />

photographer and his work renewed attention.<br />

effects<br />

his<br />

celebrities—<br />

most of<br />

wanting

<strong>Envision</strong> <strong>Equity</strong> <strong>February</strong> <strong>2019</strong><br />

James Weldon Johnson<br />

<br />

<br />

James Weldon Johnson was born in Jacksonville, Florida, on June 17, 1871, the son of a freeborn Virginian<br />

father and a Bahamian mother, and was raised without a sense of limitations amid a society focused on<br />

segregating African Americans. After graduating from Atlanta University, Johnson was hired as a principal in a<br />

grammar school. While serving in this position, in 1895, he founded The Daily American newspaper. In 1897,<br />

Johnson became the first African American to pass the bar exam in Florida.<br />

Not long after, in 1900, James and his brother, John, wrote the song "Lift Every Voice and Sing," which would<br />

later become the official anthem of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. (The<br />

Johnson brothers would go on to write more than 200 songs for the Broadway musical stage.) Johnson then<br />

moved to New York and studied literature at Columbia University, where he met other African-American<br />

artists.<br />

In 1906, President Theodore Roosevelt appointed James Weldon Johnson to diplomatic positions in Venezuela<br />

and Nicaragua. Upon his return in 1914, Johnson became involved with the NAACP, and by 1920, was serving<br />

as chief executive of the organization. Also during this period, he became known<br />

as one of<br />

the leading figures in the creation and development of the African-<br />

American artistic community known as the Harlem Renaissance.<br />

Johnson published hundreds of stories and poems during his lifetime.<br />

He also produced works such as God's Trombones (1927), a collection<br />

that celebrates the African-American experience in the rural South<br />

and elsewhere, and the novel The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored<br />

Man (1912)—making him the first black-American author to treat<br />

Harlem and Atlanta as subjects in fiction. Based, in part, on Johnson's<br />

own life, The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man was published<br />

anonymously in 1912, but did not attract attention until Johnson reissued<br />

it under his own name in 1927.<br />

After retiring from the NAACP in 1930, Johnson devoted the rest of his<br />

life to writing. In 1934, he became the first African-American professor at<br />

New York University.<br />

Johnson died in a car accident in Wiscasset, Maine, on June 26, 1938, at the<br />

age of 67. More than 2,000 people attended his funeral in Harlem.

<strong>Envision</strong> <strong>Equity</strong> <strong>February</strong> <strong>2019</strong><br />

Langston Hughes<br />

<br />

<br />

Hughes graduated from high school in 1920 and spent the following year in Mexico with his father. Around this<br />

time, Hughes' poem "The Negro Speaks of Rivers" was published in The Crisis magazine and was highly praised.<br />

In 1921 Hughes returned to the United States and enrolled at Columbia University where he studied briefly, and<br />

during which time he quickly became a part of Harlem's burgeoning cultural movement, what is commonly<br />

known as the Harlem Renaissance.<br />

But Hughes dropped out of Columbia in 1922 and worked various odd jobs around New York for the following<br />

year, before signing on as a steward on a freighter that took him to Africa and Spain. He left the ship in 1924 and<br />

lived for a brief time in Paris, where he continued to develop and publish his poetry.<br />

In 1951 Hughes published one of his most celebrated poems, "Harlem (What happens to a dream deferred?'),"<br />

discussing how the American Dream falls short for African Americans:<br />

What happens to a dream deferred?<br />

<br />

Does it dry up <br />

like a raisin in the sun?<br />

Or fester like a sore—<br />

And then run?<br />

Does it stink like rotten meat?<br />

Or crust and sugar over—<br />

Like a syrupy sweet?<br />

Maybe it just sags<br />

Like a heavy load.<br />

Or does it explode?

<strong>Envision</strong> <strong>Equity</strong> <strong>February</strong> <strong>2019</strong><br />

Lena Horne<br />

<br />

<br />

Actress and singer Lena Horne was born June 30, 1917, in Brooklyn, New York. She left school at age 16 to help<br />

support her family and became a dancer at the Cotton Club in Harlem. After having established herself as a<br />

sought after live singer, a role she would maintain throughout her life, she later signed with MGM studios and<br />

became known as one of the top African-American performers of her time, seen in such films as Cabin in the<br />

Skyand Stormy Weather. She was also known for her work with civil rights groups and refused to play roles that<br />

stereotyped African-American women, a stance that many found controversial. After some<br />

time<br />

out of the limelight during the '70s, she made a revered, award-winning comeback<br />

with her 1981 show Lena Horne: The Lady and Her Music. Continuing to record into<br />

her later years, Horne died on May 9, 2010.<br />

At age 16, Horne dropped out of school and began performing at the Cotton Club<br />

in Harlem. After making her Broadway debut in the autumn 1934<br />

production Dance With Your Gods, she joined Noble Sissle & His Orchestra as a<br />

singer, using the name Helena Horne. Then, after appearing in the Broadway<br />

musical revue Lew Leslie's <strong>Black</strong>birds of 1939, she joined a well-known white<br />

swing band, the Charlie Barnet Orchestra. Barnet was one of the first bandleaders<br />

to integrate his band, but because of racial prejudice, Horne was unable to stay or<br />

socialize at many of the venues in which the orchestra performed, and she soon<br />

left the tour. In 1941 she returned to New York to work at the Café Society<br />

nightclub, popular with both black and white artists and intellectuals.<br />

Horne was married to Louis Jones from 1937 to 1944, and they had two children. She<br />

married Lennie Hayton, a white bandleader, in December 1947 in Paris, France, but<br />

they kept their marriage a secret for three years. A union that was<br />

significantly impacted by racial prejudice, they separated in the 1960s<br />

but never divorced.<br />

Stormy Weather, a well-received biography of Lena Horne's life,<br />

was published in 2009 and written by James<br />

Gavin. Horne also published her own<br />

memoir, Lena, in 1965.

<strong>Envision</strong> <strong>Equity</strong> <strong>February</strong> <strong>2019</strong><br />

Lois Mailou Jones<br />

<br />

<br />

Lois Mailou Jones was a painter whose works reflect a command of widely varied styles, from traditional<br />

landscape to African-themed abstraction.<br />

In the 1930s, Lois Mailou Jones' art reflected the influences of African traditions, and she designed African-style<br />

masks and in 1938 painted Les Fétiches, which depicts masks in five distinct, ethnic styles. During a year in<br />

Paris, she produced landscapes and figure studies, and African influences reemerged in her art in the late 1960s<br />

and early '70s, particularly after two tours of Africa.<br />

In 1928 Jones formed and chaired the art department at the Palmer Memorial Institute in North Carolina, and<br />

two years later was recruited to teach at Howard University in Washington, D.C. Jones taught design and<br />

watercolor painting at Howard for the next forty-seven years. She mentored hundreds of students in the<br />

practicalities of an art career and took them on art tours to Europe and Africa. In 1937 Jones received a yearlong<br />

fellowship that took her to Paris to live and work. This was a defining moment for the young black artist<br />

who experienced—for the first time in her life—the complete freedom to live as she wished without the<br />

indignities of segregation that she felt in the United States. She loved Paris and Parisians. Here, she painted<br />

street scenes, still lifes, and portraits in an impressionist and post-impressionist style. Jones returned to<br />

Paris many times during her life.<br />

Jones incorporated African heritage and the American black<br />

experience<br />

into her art, responding to the challenge of African American<br />

artists<br />

associated with the Harlem Renaissance. She included African<br />

motifs in<br />

her work; later, after she married Haitian artist Louis Pierre-<br />

Noël in<br />

1953, she began spending time on this Caribbean island and added<br />

Haitian subjects to her repertoire.<br />

Jones died at age ninety-two. Her artistic legacy is recorded<br />

hundreds of her canvases—and in the passion and<br />

she communicated to some 2,500 students.<br />

in<br />

discipline<br />

Loïs Mailou Jones "Ubi Girl from Tai Region,"<br />

1972, acrylic on canvas.

<strong>Envision</strong> <strong>Equity</strong> <strong>February</strong> <strong>2019</strong><br />

Louis Armstrong<br />

<br />

<br />

Louis Armstrong was born on August 4, 1901, in New Orleans, Louisiana, in a section so poor that it was<br />

nicknamed "The Battlefield."<br />

Armstrong had a difficult childhood. His father was a factory worker and abandoned the family soon after<br />

Louis's birth; his mother, who often turned to prostitution, frequently left him with his maternal grandmother.<br />

Armstrong was obligated to leave school in the fifth grade to begin working.<br />

A local Jewish family, the Karnofskys, gave young Armstrong a job collecting junk and delivering coal. They also<br />

encouraged him to sing and often invited him into their home for meals.<br />

On New Year's Eve in 1912, Armstrong fired his stepfather's gun in the air during a New Year's Eve celebration<br />

and was arrested on the spot. He was then sent to the Colored Waif's Home for Boys.<br />

There, he received musical instruction on the cornet and fell in love with music. In 1914, the home released him,<br />

and he immediately began dreaming of a life making music.<br />

Armstrong set a number of African-American "firsts." In 1936, he became the first African-American jazz<br />

musician to write an autobiography: Swing That Music.<br />

That same year, he became the first African-American to get featured billing in a major Hollywood movie with<br />

his turn in Pennies from Heaven, starring Bing Crosby. Additionally, he became the first African-American<br />

entertainer to host a nationally sponsored radio show in 1937, when he took over Rudy<br />

Vallee's Fleischmann's Yeast Show for 12 weeks.<br />

Armstrong continued to appear in major films with the likes of Mae West, Martha<br />

Raye and Dick Powell. He was also a frequent presence on radio, and often broke<br />

box-office records at the height of what is now known as the "Swing Era."<br />

Armstrong's fully healed lip made its presence felt on some of the finest recordings<br />

of career, including "Swing That Music," "Jubilee" and "Struttin' with Some<br />

Barbecue."

Finish The Statement<br />

<br />

If I could spend one day in Harlem, New York during the<br />

Harlem Renaissance, I would...<br />

“I would dress up like the Cabaret<br />

dancers and dance as the jazz is<br />

being played.”<br />

Michelle L. Dillard<br />

Assistant Superintendent<br />

of Middle Schools<br />

Jefferson County Public Schools<br />

“I would have a long conversation<br />

with Dr. W.E.B. DuBois to talk<br />

about his next article in The Crisis<br />

Magazine about our unique<br />

perspective and intellectual<br />

contribution.”<br />

Dr. Marco Muñoz, Director <br />

Accelerated Improvement Schools <br />

Jefferson County Public Schools<br />

“I would sit in a front row<br />

seat at Harlem Theatre to<br />

enjoy Georgia Douglas<br />

Johnson’s play Blue-Eyed<br />

<strong>Black</strong> Boy!<br />

Georgia Douglas Johnson<br />

was a poet and one of earlier<br />

African-American playwrights. She was a music<br />

teacher, school principal and activist.”<br />

Geneva A. Stark, Ph.D. , CDP<br />

Diversity, <strong>Equity</strong> and Poverty Department<br />

“I would interview<br />

photographer<br />

James Van Der Zee<br />

and admire his<br />

camera collection.”<br />

Abdul Sharif<br />

Generalist of Diversity<br />

Jefferson County Public<br />

Schools<br />

“If I could<br />

spend one day<br />

in Harlem New<br />

York during the<br />

Harlem<br />

Renaissance I<br />

would…love to<br />

have separate<br />

sit downs with a<br />

restaurant<br />

owner, a barber, an educator and a<br />

musician. This would give me an<br />

opportunity to see and hear many<br />

points of views as they live in Harlem<br />

and the infusion of black culture into<br />

Americana. This would be amazing!<br />

Beam me down Scotty!<br />

Darryl W. Farmer, Principal<br />

duPont Manual High School

<strong>Envision</strong> <strong>Equity</strong> <strong>February</strong> <strong>2019</strong><br />

Marian Anderson<br />

<br />

<br />

An acclaimed singer whose performance at the Lincoln Memorial in 1939 helped set the stage for the civil rights<br />

era, Marian Anderson was born on <strong>February</strong> 27, 1897, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.<br />

The oldest of three girls, Anderson was just 6 years old when she became a choir member at the Union Baptist<br />

Church, where she earned the nickname "Baby Contralto." Her father, a coal and ice dealer,<br />

supported his daughter's musical interests and, when Anderson was eight, bought her a<br />

piano.<br />

With the family unable to afford lessons, the prodigious Anderson taught herself.<br />

At the age of 12, Anderson's father died, leaving her mother to raise her three stillyoung<br />

girls. His death, however, did not slow down Anderson's musical ambitions.<br />

She remained deeply committed to her church and its choir and rehearsed all the<br />

parts (soprano, alto, tenor and bass) in front of her family until she had perfected<br />

them.<br />

Anderson's commitment to her music and her range as a singer so impressed the rest<br />

of her choir that the church banded together and raised enough money, about $500, to<br />

pay for Anderson to train under Giuseppe Boghetti, a respected voice teacher.<br />

By the late 1930s, Anderson's voice had made her famous on both sides of<br />

the Atlantic. In the United States she was invited by President<br />

Roosevelt and his wife Eleanor to perform at the White House,<br />

the first African American ever to receive this honor.<br />

Much of Anderson's life would ultimately see her breaking<br />

down barriers for African-American performers. In<br />

1955, for example, the gifted contralto singer became<br />

the first African American to perform as a member<br />

of the New York Metropolitan Opera.<br />

Over the next several decades of her life,<br />

Anderson's stature only grew. In 1961 she<br />

performed the national anthem at President John F.<br />

Kennedy's inauguration. Two years later, Kennedy<br />

honored the singer with the Presidential Medal of<br />

Freedom.<br />

After retiring from performing in 1965, Anderson set up<br />

her life on her farm in Connecticut. In 1991, the music<br />

world honored her with a Grammy Award for<br />

Lifetime Achievement.<br />

Her final years were spent in Portland, Oregon,<br />

where she'd moved in with her nephew. She died<br />

there of natural causes on April 8, 1993.

<strong>Envision</strong> <strong>Equity</strong> <strong>February</strong> <strong>2019</strong><br />

Palmer Hayden<br />

<br />

<br />

Born Peyton Cole Hedgeman in Wide Water, Virginia, he was a prolific artist of his era. He depicted African<br />

American life, painting in both oils and watercolors.<br />

As a young man, Hayden studied at the Cooper Union in New York City and also practiced<br />

independent studies at Boothbay Art Colony in Maine. He created one of his first famous<br />

pieces in 1926, a still life called "Fetiche et Fleurs," which won the esteemed Harmon<br />

Foundation’s Gold Award, prompting his patrons to support him so he could live and<br />

study in France.Over the next five years in Paris, Hayden was very productive, trying to<br />

capture elements of Parisian society.<br />

On his return to America, Hayden began working for the United States government. He<br />

worked for the U.S. Treasury Art Project as well as the Depression-era governmentfunded<br />

Works Progress Administration (WPA).<br />

Hayden took his inspiration from the environment around him, focusing on<br />

the African American experience. He tried to capture both rural life in the<br />

South, as well as urban backgrounds in New York City. Many of these urban<br />

paintings were centered in Harlem. The inspiration for "The Janitor Who<br />

Paints" came from Cloyde Boykin, a friend of Palmer's. Boykin was also a<br />

painter who supported himself through janitorial work. Hayden once<br />

said, “I painted it because no one called Cloyde a painter; they called<br />

him a janitor.” Many people consider this painting to be an expression<br />

of the tough times Palmer was having.<br />

Palmer Hayden created a painting series on African-American folk hero<br />

John Henry. This series consisted of 12 works and took 10 years to<br />

complete. John Henry was said to be a strong, heroic man who used a hammer to<br />

create railroads and tunnel through mountains.<br />

His works had other exhibitions, including at the New Jersey State Museum and the<br />

Galerie Bernheim-Jeune.<br />

Palmer Hayden was a great artist who made many visual contributions to this<br />

country. He died on <strong>February</strong> 18, 1973.<br />

Untitled c1930 by Palmer Hayden

<strong>Envision</strong> <strong>Equity</strong> <strong>February</strong> <strong>2019</strong><br />

Richmond Barthe<br />

<br />

<br />

Trailblazing artist Richmond Barthé's sculpted works were seminal in that they focused on the lives of his<br />

fellow African Americans. He depicted African Americans at work in the fields of the South (Woman with<br />

Scythe, 1944), African Americans of distinction, and, in Mother and Son (1939), African Americans as<br />

victims of racial violence. He also sculpted images of African warriors and ceremonial participants.<br />

Barthé was born on January 28, 1901, in Bay St. Louis, Mississippi, to Richmond Barthé, Sr., and Marie<br />

Clementine Robateau. His father died before Barthé was a year old, and his mother's sewing supported the<br />

family. She later remarried, to William Franklin, an old friend and Barthé's godfather. Franklin worked in<br />

various odd jobs, including as an ice man, delivering ice throughout the rural community. According to<br />

Barthé, he was artistically inclined from a very young age. In A <strong>History</strong> of African American Artists, he is<br />

quoted as saying, "When I was crawling on the floor, my mother gave me paper and pencil to play with. It<br />

kept me quiet and she did her errands. At six years old I started painting. A lady my mother sewed for gave<br />

me a set of watercolors. By that time I could draw pretty well."<br />

After the Second World War, the world of art began to change drastically,<br />

on abstraction or distorted representations of reality. Barthé was not<br />

interested in these trends and was increasingly forgotten by the artistic<br />

establishment. As a result, Barthé began devoting much of his time<br />

to making portrait busts for wealthy New York clients, especially<br />

people involved in the theater. During and after the war, Barthé<br />

made busts of John Gielgud and Maurice Evans. Later works were<br />

of Lawrence Olivier, Katharine Cornell, and Judith Anderson. In<br />

1946, he was inducted into the National Institute of Arts and<br />

Letters. By the end of the 1940s, Barthé had grown tired of the art<br />

scene in New York (and depressed over his exclusion from it) and<br />

he bought a house in Jamaica on the advice of his doctor who told<br />

him that living in the city was hurting his health.<br />

focusing

Finish The Statement<br />

<br />

If I could spend one day in Harlem, New York during the<br />

Harlem Renaissance, I would...<br />

“I would sit and listen to<br />

Langston Hughes recite Let<br />

American Be America<br />

Again.”<br />

Cathy Gibbs - Principal,<br />

Knight Middle School<br />

“If I could spend one day<br />

in Harlem New York<br />

during the Harlem<br />

Renaissance, I would be<br />

on Broadway sitting in<br />

awe of Josephine Baker<br />

singing and dancing.”<br />

De’Nay Speaks, Ed.D.<br />

Assistant Principal<br />

Wellington Elementary<br />

School<br />

“Love to sit and listen to<br />

Langston Hughes recite his<br />

poems, especially those<br />

that were dedicated to<br />

young minds. Poems, that<br />

even today, are<br />

meaningful and relevant<br />

to our students of JCPS.”<br />

Audwin Helton,<br />

Owner of Spatial Data<br />

Integrations, Inc.<br />

“I would spend the<br />

evening in a jazz club<br />

taking in the beautiful<br />

voice of Billie Holliday.”<br />

Senior Policy &<br />

Development Advisor,<br />

Office of Mayor Greg<br />

Fischer<br />

“I would start my day by going to the Harlem YMCA which was<br />

known to host workshops which included powerhouse lecturers<br />

like Langston Hughes. Next, I would look to have lunch with<br />

W.E.B. DuBois to discuss his thoughts on the "Talented Tenth"<br />

and "Double Consciousness". To end the evening, I'd stop by<br />

the Savoy Ballroom. I couldn't imagine being in Harlem during<br />

this time and not "cutting a rug" on the maple and mahogany<br />

floor in what many of the era called the "Home of Happy Feet.”<br />

Robert E. Gunn Jr.<br />

Principal, W.E.B. DuBois Academy

<strong>Envision</strong> <strong>Equity</strong> <strong>February</strong> <strong>2019</strong><br />

Paul Robeson<br />

<br />

<br />

Paul Robeson made his career at a time when second-class citizenship was the norm for all African-Americans,<br />

who were either severely limited in, or totally excluded from, participation in the economic, political, and social<br />

institutions of America.<br />

Robeson was born on April 9, 1898, in Princeton, New Jersey. His father was a runaway slave who fought for the<br />

North in the Civil War, put himself through Lincoln University, received a degree in divinity, and was pastor at a<br />

Presbyterian church in Princeton. Paul's mother was a member of the distinguished Bustill family of<br />

Philadelphia, which included patriots in the Revolutionary War, helped found the Free African Society, and<br />

maintained agents in the Underground Railroad.<br />

At 17 Robeson won a scholarship to Rutgers University, where he was considered an athlete "without equal." He<br />

won an incomparable 12 major letters in 4 years. His academic record was also brilliant. He won first prize (for 4<br />

consecutive years) in every speaking competition at college for which he was eligible, and he was elected to Phi<br />

Beta Kappa. He engaged in social work in the local black community. After he delivered the<br />

commencement class oration, Rutgers honored him as the "perfect<br />

type of college<br />

man."<br />

Robeson graduated from the Columbia University Law School in 1923<br />

and took a job with a New York law firm. In 1921 he<br />

married<br />

Eslanda Goode Cardozo; they had one child.<br />

Robeson's career as a lawyer ended abruptly<br />

when racial hostility in the firm mounted<br />

against him. He turned to acting as a career,<br />

playing the lead in All God's Chillun Got<br />

Wings (1924) and The Emperor<br />

Jones(1925). He augmented his acting by<br />

singing spirituals. He was the first to give<br />

an entire program of exclusively African-<br />

American songs in concert, and he was one<br />

of the most popular concert singers of his<br />

time.

<strong>Envision</strong> <strong>Equity</strong> <strong>February</strong> <strong>2019</strong><br />

Chick Webb<br />

<br />

<br />

William Henry Webb (Chick Webb) was born in Baltimore, Maryland in 1909. Afflicted at birth with spinal<br />

tuberculosis which left him in poor health for his entire life, Chick was a small, hunchback of a man who<br />

possessed an “unconquerable spirit” and an astounding musical talent. For many jazz fans, Chick remains<br />

arguably the greatest jazz drummer to have ever played the instrument. Yet it was only by a quirk of fate<br />

that Chick even came to play the drums.<br />

The idea of playing the instrument was suggested to him by his doctor as a way to “loosen<br />

stiffened limbs. By saving money earned through delivering<br />

papers, Chick soon secured a drum set. And by the age of<br />

seventeen, Chick was playing in New York nights clubs such<br />

as the <strong>Black</strong> Bottom and the Paddock Club. These early jobs<br />

were secured for him through the efforts of Duke Ellington who<br />

instantly recognized Chick’s talent. It was Ellington who<br />

encouraged Chick to form a quintet aptly called the<br />

“Harlem Stoppers.” The name was probably derived<br />

from Chick’s own hard driving style on the drums as the<br />

quintet’s leader. Later, this quintet would evolve into one of the<br />

most feared “swing” bands in New York—The Chick Webb<br />

Orchestra.<br />

Chick Webb’s already mythical reputation was given even greater<br />

stature when he replaced his longtime vocalist Charles Linton with<br />

a then relatively unknown singer by the name of Ella Fitzgerald.<br />

Jazz legend has it that Ella “snuck” into Chick Webb’s dressing<br />

room in order to convince him to take her into his bed. But<br />

legends notwithstanding, Ella did become Chick’s lead vocalist.<br />

And Ella, called adoringly by fans and musicians, “The First Lady<br />

of Swing,” always acknowledged Chick Webb as her “first and foremost”<br />

influence.<br />

up” his<br />

Together, Chick and Ella, would electrify the Swing era of jazz with hits such<br />

as "A-Tisket a Tasket," which was composed by Ella to cheer Chick up while<br />

he was ill. And while this and other great tunes recorded by these artists are wellknown,<br />

Chick’s early work—some say his most impressive solos—was regrettably<br />

poorly<br />

captured by recording technology ill suited for Chick’s immense talent. But one of Chick’s hit tunes “Stompin’ at<br />

the Savoy” gives contemporary jazz fans some hint of the power of Chick Webb and his Orchestra.<br />

In 1938, Chick Webb’s health began to fail him. This was mostly due to Chick’s chronic spinal condition and his<br />

insistence that he and his orchestra would only perform at the height of their talents for their fans. Often it was<br />

said that Chick played with such power that he was physically exhausted when he left the bandstand.<br />

In 1939, Chick returned to Baltimore for a major operation. Shortly afterwards, the little giant died on June 16,<br />

1939 with his mother at his side. Chick’s funeral procession was said to have been composed of some eighty cars<br />

and the church where he was eulogized was said to be unable to hold all the mourners.

Finish The Statement<br />

<br />

If I could spend one day in Harlem, New York during the<br />

Harlem Renaissance, I would...<br />

“If I could spend one day in Harlem New Your during the Harlem<br />

Renaissance, I would love to catch one of Billie Holiday’s<br />

performances with Louis Armstrong at the Cotton Club, while hanging<br />

out with W.E.B DuBois, discussing the issues of the day.”<br />

Manuel Garr, MSLS, MCP<br />

Software Developer II (Business Intelligence)<br />

JCPS Information Technology<br />

“If I could spend one day in Harlem New York during the<br />

Harlem Renaissance, I would sit down with Langston Hughes<br />

and share my poetry and ask him to write a few jazz rhythms<br />

with me.”<br />

Tracy Barber <br />

Principal, Dunn Elementary<br />

“I would ask Langston Hughes to describe what he thinks is missing<br />

from America based on this stanza in his poem, Let America be<br />

America Again. Together I can see us having a great discussion on<br />

the parallels of <strong>2019</strong> America and the Renaissance era and how even<br />

today the fight continues.<br />

Jasmine Hollins Drinkard<br />

Professional School Counselor

<strong>Envision</strong> <strong>Equity</strong> <strong>February</strong> <strong>2019</strong><br />

Claude McCay<br />

<br />

<br />

Claude McKay, born Festus Claudius McKay, was a key figure in the Harlem Renaissance, a prominent literary<br />

movement of the 1920s. His work ranged from vernacular verse celebrating peasant life in Jamaica to poems<br />

challenging white authority in America, and from generally straightforward tales of black life in both Jamaica<br />

and America to more philosophically ambitious fiction addressing instinctual/intellectual duality, which McKay<br />

found central to the black individual’s efforts to cope in a racist society. Consistent in his various writings is his<br />

disdain for racism and the sense that bigotry’s implicit stupidity renders its adherents pitiable as well as<br />

loathsome. As Arthur D. Drayton wrote in his essay “Claude McKay’s Human Pity”: “McKay does not seek to<br />

hide his bitterness. But having preserved his vision as poet and his status as a human being, he can transcend<br />

bitterness. In seeing ... the significance of the Negro for mankind as a whole, he is at<br />

once<br />

protesting as a Negro and uttering a cry for the race of mankind as a member<br />

of<br />

that race. His human pity was the foundation that made all this possible.”<br />

A London publishing house produced McKay's first books of verse, Songs<br />

of Jamaica and Constab Ballads, in 1912. McKay used award money that<br />

he received from the Jamaican Institute of Arts and Sciences to move to<br />

the United States. He studied at the Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee<br />

University) and Kansas State College for a total of two years. In 1914, he<br />

moved to New York City, settling in Harlem.<br />

No more for you the city's thorny ways,<br />

The ugly corners of the Negro belt;<br />

The miseries and pains of these harsh days<br />

By you will never, never again be felt.<br />

No more, if still you wander, will you meet<br />

With nights of unabating bitterness;<br />

They cannot reach you in your safe retreat,<br />

The city's hate, the city's prejudice!<br />

'Twas sudden--but your menial task is done,<br />

The dawn now breaks on you, the dark is over,<br />

The sea is crossed, the longed-for port is won;<br />

Farewell, oh, fare you well! my friend and lover.<br />

Rest In Peace - Poem by Claude McKay

<strong>Envision</strong> <strong>Equity</strong> <strong>February</strong> <strong>2019</strong><br />

Florence Mills<br />

<br />

<br />

Florence Mills was born Florence Winfrey on January 25, 1896 (some accounts say 1895), in the Washington,<br />

D.C., area. She became an entertainer as a young child, billed as "Baby Florence" and captivating audiences with<br />

song and dance. She worked in vaudeville and joined a touring company at eight years old before authorities<br />

found out she was underage. Her family eventually moved to Harlem, New York, and in 1910 Mills would form<br />

another vaudeville act—the Mills Sisters—with her siblings Olivia and Maude. Mills would later meet and wed<br />

Ulysses S. Thompson, from the troupe the Tennessee Ten, in 1923.<br />

In 1921, Mills was hired to replace Gertrude Saunders in the Eubie<br />

Blake and Noble Sissleproduction Shuffle Along, which was a<br />

trailblazing musical with an all African-American creative team.<br />

The Off-Broadway show was a hit, and Mills became renowned for<br />

her performances, highlighted by the tune "I’m Craving for That<br />

Kind of Love."<br />

Mills earned a reputation for her wondrous high-pitched voice,<br />