You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

1

Table<br />

Of<br />

Contents<br />

The Council of Clermont<br />

Pope Urban II Q&A<br />

The People's Crusade<br />

The Arrival at Constantinople<br />

Profile: Raymond of Toulouse<br />

The Siege of Nicea<br />

Profile: Bohemond of Taranto<br />

The Battle of Dorylaeum<br />

The Capture of Edessa<br />

The Siege of Antioch<br />

The Battle of Antioch<br />

The Siege of Jerusalem<br />

Defender of the Holy Sepulchre and<br />

the Battle of Ascalon<br />

Stephen of Blois Q&A<br />

Letters<br />

Editorial<br />

Bibliography<br />

Meet the Writers<br />

3<br />

8<br />

1 2<br />

1 7<br />

23<br />

26<br />

29<br />

33<br />

37<br />

39<br />

43<br />

52<br />

58<br />

62<br />

65<br />

68<br />

73<br />

Margarita Bajamic<br />

"May I please have<br />

bread?"<br />

Julia Banco<br />

"Padre Pio save us"<br />

Cole Canofari<br />

"Educate, evaluate,<br />

procrastinate"<br />

Mika Colonia<br />

"DK! Donkey Kong is<br />

here!"<br />

2<br />

Vanessa DaSilva<br />

"It's not a noun"<br />

Romina Difluri<br />

"It's a noun"<br />

Marlon Miral<br />

"Expect nothing,<br />

appreciate everything"<br />

Alessio Pizzolato<br />

"Trust me, you can<br />

dance" -vodka

The Council<br />

of Clermont<br />

Romina Difluri<br />

Born to a family of French nobles in<br />

1 042, there was nothing particularly exceptional<br />

about Odo de Lagéry in his childhood. His youth<br />

was spent in relative comfort given the time<br />

period, enjoying the quality life he, fortunately,<br />

had been assigned at birth (Runciman 56). Soon<br />

enough, however, it became evident that God had<br />

granted him a superior wealth of talent,<br />

intelligence, and integrity to match his. Still, no<br />

one could have possibly foreseen the extent that<br />

this man would single-handedly have on our<br />

Earth. It was impossible to predict that, one day,<br />

he would abandon his given name and be reborn<br />

as Pope Urban II; that glorious battles, sieges,<br />

and pilgrims would be called in his name; that he<br />

would conjure the cries of hundreds of men,<br />

“Deus vult!”, “God wills it!” (Armstrong 3); that<br />

the very fabric of human society as we know it<br />

today exists as a result of his actions. Whether or<br />

not he intended to be, Pope Urban the II was,<br />

arguably, one of the most significant figures in<br />

the history of mankind. His speech at the Council<br />

of Clermont in 1 095 would alter the course of<br />

history forever by initiating one of the most<br />

notorious, controversial sequences of events in<br />

the Middle Ages, The First Crusade (Runciman<br />

62).<br />

It was November 25th in the winter of 1 095,<br />

and “twelve archbishops, eighty bishops and other<br />

senior clergy” (Frankopan 1 ) had been summoned<br />

to a synod at Clermont in Auvergne. Most of the<br />

council was held in the presence of these clergymen<br />

as is typical of a synod, though Pope Urban II<br />

announced that he had an announcement meant to<br />

be heard by anyone of the Christian faith.<br />

(Runciman 56). He assembled this group of the<br />

faithful in a nearby field, addressing the crowd of<br />

highly expectant laymen and clergymen alike.<br />

Before even beginning, the audience was held in<br />

the palm of his hand; Urban II was well-liked by<br />

most and had already proved himself well worthy<br />

of their admiration. His role in the Church had<br />

begun decades ago as prior to the Abbot of Cluny,<br />

though that is only one of the many titles on his<br />

formidable resume. Pope Gregory VII would<br />

eventually make him Cardinal-Bishop of Ostia and<br />

move him to Rome. There, he would serve as friend<br />

and advisor to the Pope, even acting as legate on<br />

his behalf in France and Germany (Runciman 56).<br />

Following the death of Pope Gregory VII, which<br />

Pope Urban II witnessed in person, Pope Victor III<br />

was instated as Bishop of Rome. Urban II was not<br />

quite as fond of this new Pope, though he was quite<br />

fond of Urban II and even recommended him as a<br />

potential successor. He was elected Pope as Urban<br />

II in March of 1 088, and from that moment on fate<br />

was sealed (Runciman 56).<br />

Meanwhile, the Byzantine Empire in<br />

Constantinople to the East was experiencing serious<br />

difficulties. After the fall of the Roman Empire, its<br />

two halves were ostracized from each other,<br />

forming intense prejudices between Romans and<br />

Byzantines, deeply rooted in both political and<br />

3

eligious disagreements. (Jones 3). Despite the<br />

nature of the Primacy of Peter which was clearly<br />

in the possession of the Roman Pope, the<br />

Byzantines took it upon themselves to form their<br />

own Church and establish an Antipope, Guibert.<br />

For decades following this decision, the Roman<br />

and Byzantine Empires did not have particularly<br />

amicable relationships. While the Romans were<br />

faced with fending off the Barbarians,<br />

Constantinople had a conflict on their own to<br />

deal with. The Seljuk Turks had been threatening<br />

the Byzantines for some time, and eventually<br />

defeated them ruthlessly at the Battle of<br />

Manzikert in 1 071 (Jones 3). Using this as an<br />

entryway, they then continued to sweep through<br />

the Middle East, eventually reaching and<br />

occupying Jerusalem, the Holy Land. In a crisis<br />

of desperation, Byzantine Emperor Alexius I<br />

Comnenus wrote a letter to Pope Urban II,<br />

pleading for help with the Muslims in Jerusalem.<br />

When Pope Urban had assembled his crowd of<br />

the faithful, they expected the usual messages to<br />

be conferred on - matters of Cluniac reformation<br />

and combatting Church corruption. No one ever<br />

expected him to suggest they answer the call<br />

from the Byzantine Empire (Runciman 56).<br />

Shockingly enough, historians posses no<br />

actual transcript of this incredibly pivotal speech.<br />

At the time, nobody had thought to write it<br />

down. We do, however, have five versions<br />

written by a variety of people, documented a<br />

year or two after its occurrence. The Version of<br />

Robert the Monk is referenced fairly commonly,<br />

as it is believed he may have been present for the<br />

speech (Peters 2). The Gesta version, however, was<br />

one of the earlier ones to be written, therefore many<br />

of the other four used it as a template for theirs. It<br />

was written by an anonymous crusader who likely<br />

was not a witness (Peters 5). Third, there is The<br />

Version of Baldric of Dol. He used the Gesta<br />

version heavily when writing his, therefore the two<br />

are relatively similar (Peters 6). The Version of<br />

Guibert Nogent was penned by a man who most<br />

definitely was present for the speech. He did not<br />

personally partake in the crusade, but was a sort of<br />

amateur historian and very knowledgeable on the<br />

matter (Peters 1 0). Lastly, we have the Fulcher of<br />

Chartres, “the most reliable of sources” (Peters 1 7).<br />

Fulcher was present for the speech and very<br />

involved in multiple aspects of the crusades. He<br />

had personal connections with princes, spoke to<br />

leaders, and followed the crusaders around on their<br />

journeys. Fulcher chronicled the entirety of the<br />

First Crusade, including his own version of Pope<br />

Urban II’s speech (Peters 1 7).<br />

Though each version of Urban’s speech<br />

differs from the other, there are several main points<br />

that Urban makes and uses that appear in all five.<br />

Urban exercises masterful rhetoric in his persuasion<br />

of the crowd through five foolproof steps. In his<br />

opening statement from Robert the Monk, Urban<br />

appealed to the French noblemen in the crowd,<br />

calling them a “race chosen and beloved by God”<br />

(Peters 2). By complementing the Franks, it was<br />

only human nature for them to have been more<br />

inclined to listen.<br />

4

Next, he absolutely barraged his audience<br />

with the terrible atrocities the Muslims were<br />

allegedly committing in their Holy Land. These<br />

examples are numerous, though one of the most<br />

harrowing claims they “circumcise the<br />

Christians, and the blood of the circumcision<br />

they either spread upon the altar or pour into the<br />

vases of the baptismal fonts” (Peters 2). This was<br />

a key factor, as it sparked an intense hatred at the<br />

audacity of the Muslims. It gave the Christians a<br />

reason to not just hate but absolutely despise<br />

them, to feel the duty to stop them from ruining<br />

the land that Jesus himself had lived on.<br />

This second point leads directly to the<br />

third, guilt. Pope Urban II made the audience feel<br />

like it was their own personal responsibility to do<br />

something about the crisis. The Fulcher of<br />

Chartres documented that he bid them, “if you<br />

permit them to do so, God will be much more<br />

widely attacked by them” (Jones 71 ) Though it<br />

may not be clearly apparent, Urban II was very<br />

intentional in his wording. He personally<br />

addressed each member of the audience by<br />

saying “you,” (Jones 71 ) and by saying that God<br />

would be attacked if they did nothing makes it<br />

incredibly difficult not to feel guilty for choosing<br />

to stay behind. “It was shameful that the tomb of<br />

Christ should be in the hands of Islam”<br />

(Armstrong, 1 ), he professed. Lastly, Urban<br />

motivated them with gifts, dangling incentives in<br />

front of their faces like candy. He promised the<br />

crusaders the ability to bypass Purgatory and<br />

make it straight to Heaven, promised them they<br />

would come home as heroes, that land and<br />

wealth would be waiting for them when they<br />

returned. After a speech of this calibre, it was no<br />

surprise that he was met with uproarious support.<br />

Whether or not their perspective on Muslims was<br />

accurate, embellished, or way off, that entire<br />

crowd shared the exact same opinion by the time<br />

Urban II was done. “Deus vult!” They cried,<br />

“God wills it!” (Amstrong 3). The Bishop of<br />

Lupoy stood up in his seat before Urban was<br />

hardly able to finish, declaring that he would join<br />

him and taking up arms, inciting hundreds to<br />

immediately follow his example (Runciman 62).<br />

It is speculated that Pope Urban II had three<br />

main motives supporting his decision to answer<br />

Alexius I Comnenus’ calls, despite their rather<br />

turbulent relationship. Primarily, it was a wise<br />

choice on religious grounds. As mentioned<br />

previously, the Holy Land of Jerusalem, where<br />

Jesus was crucified and resurrected, was under the<br />

control of Seljuk Turks. These people were a<br />

“warrior-like” (Jones 3) tribe that had converted to<br />

Islam, adopting an extremist position of the faith,<br />

essentially forming their own Muslim sect. The<br />

Christians, however, were unaware of this division<br />

within the Muslims, and believed them all to be<br />

part of the newly powerful extremist sect. This<br />

radical group occupied Jerusalem and would attack<br />

anyone who attempted to come visit. Though this<br />

may appear to be simply an unfortunate<br />

inconvenience, it had serious ramifications on the<br />

Christian Church. Up until that point, it had been<br />

common for Christians to go on pilgrimages to the<br />

Holy Land. There, they could visit the grounds that<br />

Jesus himself had tread, strengthening their faith<br />

and returning home spiritually anew. Now, the<br />

Muslims would attack anyone who dared to attempt<br />

and visit, making a pilgrimage incredibly<br />

dangerous and near impossible. Guibert of Nogent<br />

wrote that Urban was distraught to learn<br />

“Christianity was established where now is<br />

paganism” (Peters 1 3). By sending men over to<br />

Jerusalem on an armed pilgrimage (Armstrong 59),<br />

they might “destroy that vile race from the lands of<br />

our friends” (Jones 70) and be able to resume their<br />

safe, nonviolent pilgrimages. (Jones 71 ).<br />

Pope Urban II’s second reasoning had to do<br />

with the long-due reparations needed concerning<br />

the Great Eastern Schism. During the time of<br />

Urban’s papacy, what was left of the Roman<br />

Empire was in shambles. Pope Urban II would<br />

constantly have to deal with the complications the<br />

Eastern Orthodox Church had presented. By<br />

creating a second Church, the Christian Church was<br />

thrown into a period of chaos and confusion, both<br />

Pope and Antipope attempting to assume Peter’s<br />

Primacy. Rome and Constantinople were constantly<br />

at odds, the Byzantine Empire maintaining their air<br />

of superiority as per usual. Pope Urban II realized<br />

how rare the opportunity to amend the broken<br />

5

elationship between the East and West was, and cleverly figured it would be beneficial to continue repairing<br />

things between the two Empires. Urban II recognized the potential of amending Christendom and the<br />

harmony that was meant to exist between pope and Emperor. Additionally, this was Urban II’s chance to<br />

fulfill the desires of his predecessor, Pope Gregory VII. In 1 071 and 1 074, Pope Gregory VII had attempted to<br />

defend the Church “in response to Turkish victories against Byzantium (Armstrong 63). Unfortunately, very<br />

few knights were persuaded to join the Knights of St. Peter, and nothing would ever come of Gregory’s call to<br />

arms. Pope Urban’s “appeal to the knights of Europe twenty years later” (Armstrong 63) would incur an<br />

incredibly different response, allowing him to fulfill Pope Gregory VII’s original plans (Armstrong 63).<br />

Lastly, the people under Pope Urban II’s care had fallen into disarray in every aspect imaginable. The<br />

continent was “torn apart by small wars” (Jones 2), riddled by the petty, now violent arguments of “nobles<br />

with too much time on their hands” (Jones 2). The knights of the Roman Empire had begun to act terribly<br />

hostile towards one another, constantly fighting and making messes all throughout the Empire. Countless<br />

younger siblings who were denied an inheritance by their elder brothers’ and their claims would furiously<br />

attack one another in the streets. Hundreds of unemployed soldiers similarly invented ways to cause trouble,<br />

often forming gangs and infecting the towns with the plight of gang-warfare (Jones 3). Though Pope Urban II<br />

may have lacked the passion of Gregory VII, he was “broad-minded, less obstinate, and more skillful in<br />

handling men” (Runciman 57). Identifying the futile violence spotting up all over the Empire, he realized that<br />

an armed pilgrimage would be the perfect way to send these troublesome men out of the cities, now armed<br />

with a purpose to fuel their violence. It was a wonderfully practical solution (Jones 3).<br />

It is important to note that Urban had specific, practical intentions with his initiations of the crusades.<br />

In fact, he never even used the word to describe his endeavours. Pope Urban II wanted an armed pilgrimage<br />

not vengeful battle, and this is an important distinction. He intended for a group of trained, noble knights to<br />

pick up their arms and travel to the Holy Land on a mission of faith. The goal was never to slaughter Muslims<br />

and destroy them all. He also made it clear in the version of Robert the Monk that it was not necessary for the<br />

poor, any women, the elderly, or untrained to come along, as they would only be a hindrance and burden<br />

(Peters 4). Their goal was simply meant to be to go on a pilgrimage, exercising their right to worship the<br />

Lord. If they had to defend themselves from the Turks, then so be it. Ultimately, however, it was a practical,<br />

logical solution to three problems the Church and Pope Urban II himself had been plagued with for years.<br />

Unfortunately, the execution of Urban’s goal was , to say the least. Whether or not he intended it to be, Pope<br />

Urban II speech at the Council of Clermont was the seed that sprouted two centuries worth of conflict,<br />

beginning with the First Crusade (Peters 2).<br />

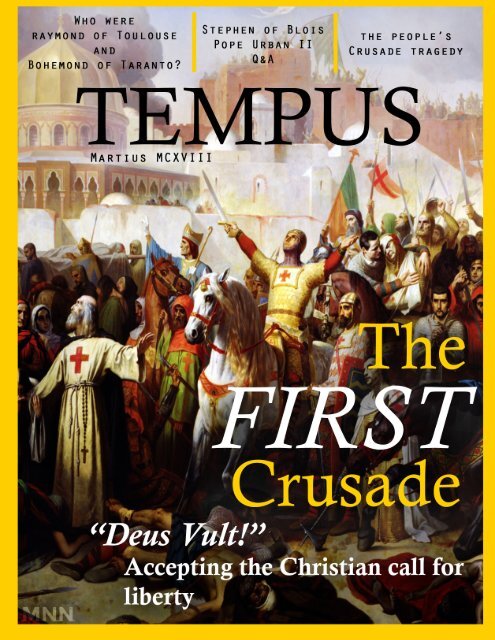

Urban delivers his speech during the Council ofClermont<br />

6

7

An Interview with<br />

8<br />

Marlon Miral<br />

Today, we are joined by Pope Urban II, the pious<br />

vicegerent who “transformed the ethos of the<br />

Holy Roman Empire with regard to holy war and<br />

pilgrimage” (Ross 575). This inspiring and Godfearing<br />

figure answers the circulating questions<br />

on his personal life, the Council of Clermont, and<br />

life after the First Crusade.<br />

Q: Pope Urban II, as a child, did you want to<br />

join the religious life or did you have other<br />

aspirations?<br />

A: Well, the Lagèry family doesn’t shy away<br />

from living a luxurious life, keeping in mind that<br />

I come from a family of aristocrats. Interestingly<br />

enough, it was not something I thought about in<br />

school. After studying in Soissons and Reims, I<br />

became fascinated with the Church and it was<br />

only then where I heard God’s calling for me.<br />

Soon after, I became the archdeacon in the<br />

diocese of Reims, where I would assist the<br />

bishop with administration concerns. A couple of<br />

years later, I entered the Cluny Abbey to become<br />

a monk under the influence of Abbot Hugh.<br />

Then, I was sent on a mission to Rome, where I<br />

was appointed as a cardinal by Pope Gregory<br />

VII. Subsequently, I was elected pope by a group<br />

of reform cardinals who were trying to regain<br />

control of Rome from the antipope, Clement III.<br />

Now, I am known as Pope Urban II (Becker<br />

“Urban II”).<br />

Q: Very interesting story. Fast forward a<br />

couple of years and we are taken to the<br />

Council of Clermont. What was discussed at<br />

the Council of Clermont?<br />

A: Twelve archbishops, eighty bishops, and<br />

countless lay men were present with me at the<br />

Council of Clermont (Frankopan 1 ). In the<br />

beginning, we discussed the Muslims’ acts of<br />

transgression in Jerusalem. Christians were being<br />

persecuted by the Muslims and it was our<br />

responsibility as leaders of the Church to start a<br />

movement and take back the Holy Land. Then, I<br />

called upon all Christian knights and nobles across<br />

Europe. I invited them to embark on this pilgrimage<br />

to the Holy Land and promised that their souls<br />

would be cleansed if they chose to partake. Finally,<br />

I appointed Adhemar of Le Puy to lead this crusade<br />

and enkindle the crowd (Cartwright “Council of<br />

Clermont”).<br />

Q: What inspired you to call the First Crusade?<br />

A: Well, there were a number of factors that led me<br />

to call this crusade. I had three main motives that<br />

led me to respond to the calls of Alexius<br />

Comnenus. During this time, Jerusalem was under<br />

the control of the Seljuk Turks. They were<br />

preventing Christians from entering the Holy Land<br />

and inflicting violence on anyone who had dared to<br />

visit. I also wished to repair the Great Eastern<br />

Schism. The Eastern Orthodox Church was in<br />

conflict with the Roman Catholic Church. Two<br />

figures claiming the Primacy of Peter had thrown<br />

the Church into a period of confusion. Calling a<br />

crusade would amend the severed relationship<br />

between the East and West and amend Christendom<br />

once and for all. Finally, I wished to redirect the<br />

spewing violence that was spotting up all over the<br />

Empire. Knights and nobles were beginning to act<br />

hostile with one another, thus calling a pilgrimage<br />

would present a perfect opportunity to cast away<br />

these intemperate men with a real purpose. In<br />

reality, this crusade was a defensive just war rather<br />

than one of despicable intentions (Asbridge 1 6-21 ).<br />

Q: How did you convince so many people to go<br />

on this pilgrimage of yours?<br />

A: In summary, I proclaimed an indulgence for<br />

anyone who participated in the Crusade. Any<br />

crusader who died on this pilgrimage received a<br />

remission of sins and the privilege of bypassing

Pope Urban II<br />

Purgatory (Asbridge 37). I had a group of<br />

scholars come up with the idea that “a campaign<br />

of violence could be justified by references to<br />

particular passages of the Bible and the works of<br />

Saint Augustine of Hippo” (Cartwright “Council<br />

of Clermont”). The objective of this crusade was<br />

liberation and this is what we achieved.<br />

Q: Do you firmly believe that calling a<br />

crusade was the right decision to make? In<br />

other words, if you could go back in time,<br />

would you make the same decision?<br />

A: Yes. As I said before, my intentions were not<br />

to kill any Muslims but rather to reach a peaceful<br />

negotiation. When this was deemed unfeasible, a<br />

crusade to liberate Jerusalem was the next best<br />

option. I intended for a group of trained nobles<br />

and knights to travel to the Holy Land on a<br />

mission of faith. All we ever asked from the<br />

Seljuk Turks was to exercise our right to worship<br />

our Saviour. The violence that erupted was<br />

simply employing self-defence against the Seljuk<br />

Turks. All in all, the results seemed to work in<br />

our favour and that is all that needs to be said.<br />

Q: Describe your relationship with Byzantine<br />

Emperor Alexius Comnenus.<br />

A: To be honest with you, Alexius and I weren’t<br />

on the greatest terms before he asked for my<br />

help. With the whole Great Eastern Schism going<br />

on, the Church was forced into a period of<br />

confusion. Charlemagne’s crowning is what<br />

seemed to evoke some tension. Now, the<br />

Byzantine Emperor had no real connections with<br />

the Church. The creation of the Eastern Orthodox<br />

Church ultimately severed all connections<br />

between the Byzantine Empire and the Roman<br />

Catholic Church (Meyendorff “Eastern<br />

Orthodoxy”). I have to admit that I was quite<br />

surprised to hear from Alexius Comnenus. He<br />

informed me that the Seljuk Turks were<br />

threatening him for quite some time and that the<br />

Holy Land was under Muslim control now. He<br />

asked me to assemble an army of knights and take<br />

back the Holy Land. At this point, I felt compassion<br />

for him and figured it was time to act upon this<br />

request (Runciman 56).<br />

Q: How did you convince so many people to go<br />

on this pilgrimage of yours?<br />

A: In summary, I proclaimed an indulgence for<br />

anyone who participated in the Crusade. Any<br />

crusader who died on this pilgrimage received a<br />

remission of sins and the privilege of bypassing<br />

Purgatory (Asbridge 37). I had a group of scholars<br />

come up with the idea that “a campaign of violence<br />

could be justified by references to particular<br />

passages of the Bible and the works of Saint<br />

Augustine of Hippo” (Cartwright “Council of<br />

Clermont”). The objective of this crusade was<br />

liberation and this is what we achieved.<br />

Q: Do you believe that God looks favourably<br />

upon you considering the decisions you made?<br />

A: You know you’re really testing my patience? As<br />

I mentioned before, I did not wish for any innocent<br />

man to be killed. This was simply an act of defense<br />

against the Seljuk Turks. In Jerusalem, the Jews<br />

were conspiring with the Turks and were standing<br />

in our way of capturing the Holy Land. I’ve spent<br />

my whole life praying for those who persecute me.<br />

I’ve devoted my whole life to God who has<br />

showered me with blessings. If I have done<br />

something that has upset him, that is between us<br />

two. Next question.<br />

Q: You make some outstanding points here. Why<br />

didn’t you ask Henry IV, the Holy Roman<br />

Emperor to assist you in calling this crusade?<br />

9

A: I regret to inform you that the two of us are not on speaking terms. I don’t like to hold grudges but I will<br />

never overlook the fact that he appointed Clement III and convinced him to lay claim to the Primacy of Peter<br />

(Schmale “Henry IV”). He had no right to complete such a heinous maneuver. I proposed the idea of a<br />

religious pilgrimage, therefore I had every right do so without the approval of the Holy Roman Emperor. The<br />

social order of Christendom calls for the Emperor to provide protection for the Church and take care of the<br />

earthly needs of the people. Henry IV failed to reach out and support this religious pilgrimage, which displays<br />

a lack of committment on his part. The only one who can judge him now is the one who presides over us.<br />

Q: Last question. Arguably saving the best for last. Historians have yet to find a complete transcipt of<br />

your inspiring speech at the Council of Clermont. Did you actually start the chant ‘Deus Vult’?<br />

A: I knew this question would be asked. However, my response may not be well received. The truth is that the<br />

details are insignificant. My general message to the audience contained the idea that God wanted us to take<br />

back the Holy Land and that he was counting on us to do so. Maybe a chant of ‘Deus Vult’ did break out.<br />

We’ll never know. The wording is not important but rather the message I had to express. They bore this<br />

common meaning. Anyway, thank you for lovely questions <strong>Tempus</strong> Magazine. May the blessing of the Lord<br />

be upon you all.<br />

1 0

11

The People's<br />

Crusade: A<br />

Complete Failure<br />

1 2<br />

Julia Banco<br />

After Pope Urban II's sermon at<br />

Clermont, in November 1 095, calling for<br />

Christians to take back the Holy Land held by<br />

the Seljuk Turks (Jones 9). He was expecting a<br />

powerful military force charged by nobles,<br />

knights, and foot soldiers who possessed military<br />

expertise and experience (Madden 39). While<br />

Pope Urban II's speech resulted in a compelling<br />

appeal to nobles and military men to fight, it also<br />

intrigued many serfs, peasants, poor people, and<br />

minor nobles of all ages and sexes (Phillips &<br />

Taylor 46). This was surprising to Urban in<br />

which he advocated that the old, feeble, women<br />

without the consent of their husbands, and clergy<br />

members without the consent of their clergy<br />

should not join, yet they did (Hanawalt 80).<br />

Many people were convinced to join due<br />

to the circulating idea the second coming of<br />

Christ was coming soon. Comets, lunar eclipses,<br />

and meteor showers indicated that it might be<br />

God sending a message. When multitudes of<br />

people began getting ill, many people speculated<br />

that it was God’s displeasure with them. With<br />

Peter the Hermit and Pope Urban II preaching<br />

upon these radical ideas, many people desired a<br />

pilgrimage (Phillips & Taylor 47). Unfortunately,<br />

this was not possible due to the Seljuk Turks<br />

holding the Holy Land of Jerusalem. The Turks<br />

defiled churches and religious landmarks, robbed<br />

and displayed violence towards the Christians<br />

upon them visiting. From their actions, this news<br />

swept throughout Europe and all of Europe was<br />

afraid of the Turks. From these responses, people<br />

like Peter the Hermit preached for peasants and<br />

common people to fight the Turks to rightfully<br />

take Jerusalem back. (Lambert 78). One would not<br />

think this would be influential and that the Turks<br />

brought fear, but due to Peter the Hermit’s ability to<br />

attract large crowds and his evangelical ideas, he<br />

had found himself leading what is known as The<br />

People’s Crusade (Philips and Taylor 46).<br />

Peter the Hermit invited clergymen, sinners,<br />

and serfs on his journey to recapture the Holy Land.<br />

He portrayed Jerusalem as the promised land<br />

“flowing with milk and honey,” as said in the<br />

scriptures. When serfs, peasants, and slaves heard<br />

this they believed they could be liberated from the<br />

starvation and slavery that they were living in<br />

(Lambert 78). This invitation and promise from<br />

Peter the Hermit had over one hundred thousand<br />

people joining him by the end of the crusade<br />

(Williams 41 ). Although Peter had numerous<br />

people to fight the Turks, many of the people who<br />

joined had little to no military experience (Phillips<br />

& Taylor 46). The people who joined the crusade<br />

not only had no experience fighting, but they also<br />

had no armour, weapons, or horses to fight with.<br />

Very few of them knew how to carry a sword, but

Peter thought they could succeed because they<br />

had the weapon of prayer (Williams 39).<br />

Fortunately, he had assembled minor nobles with<br />

some military experience like Walter Sans Avoir<br />

from the Seine Valley (41 ).<br />

Walter Sans Avoir was a tremendous help<br />

in the People’s Crusade and aided militarily. He<br />

was a moderately experienced soldier and<br />

brought eight experienced knights and fifteen<br />

thousand-foot soldiers to the People’s Crusade<br />

(Foss 57). Together they had found themselves<br />

successful in recruiting members throughout<br />

Europe. They began their journey to the Holy<br />

Land on April 1 2, 1 096, both leading a wave of<br />

peasants for the People’s Crusade. Peter began in<br />

Cologne, Germany and Walter left from<br />

Clermont, France. Peter’s plan was to gain more<br />

followers as he continued throughout Germany<br />

and did this by preaching that Jesus had<br />

appointed him to lead the crusade (Philips and<br />

Taylor 46). With the more people that joined and<br />

the supplies running low, the crusaders needed to<br />

acquire more. The only feasible idea in which<br />

they could get supplies was to start stealing from<br />

the Jewish people starting in the Rhineland<br />

(Williams 41 ).<br />

To the Christians, persecuting the Jews<br />

for their money was not a poor plan since they<br />

held many anti-semitic ideas at the time and for<br />

other reasons. One of them was that money<br />

lending was forbidden between Christians and in<br />

order to get resources, they would need to get it<br />

elsewhere. Christians usually entered debt with<br />

Jewish leaders, so instead of borrowing money,<br />

they stole from Jewish communities<br />

(Phillips & Taylor 47). Count Emicho of Leiningen,<br />

a minor noble recruited by Peter, had a heavy<br />

influence on the treatment of the Jewish people<br />

throughout the crusade. He held many anti-semitic<br />

ideas such as the Jews were responsible for the<br />

crucifixion of Christ and spread them throughout<br />

the crowd of the crusaders (Lambert 78). He<br />

claimed to the army that Christ appeared to him and<br />

promised to make him emperor as long as he<br />

converted the Jewish people of Europe. With many<br />

people believing Count Emicho, Count Emicho<br />

commenced a ten-thousand-man army that did not<br />

reach the Holy Land, and instead focused on<br />

carrying out attacks on Jewish communities in<br />

France and Germany (Phillips & Taylor 47).<br />

The first attacks upon the Jews led by Count<br />

Emicho started in Cologne, the same city where<br />

Peter the Hermit’s first wave of the crusade left,<br />

and then the Northern neighbouring cities, Mainz<br />

and Worms. The cruelty put against the Jewish<br />

communities of Cologne, Mainz, and Worms was<br />

relentless, in which the crusaders did not spare<br />

women, children, or the elderly (Frankopan 1 20).<br />

Count Emicho and his ten-thousand-man army<br />

equipped with knives, swords, and clubs charged<br />

towards a small part of Worms called the<br />

“Judengasse” or the “Jew’s Gate.” There they<br />

hacked every Jew in sight, pillaged the town, and<br />

burnt down the Synagogue with Jews inside. When<br />

the crusaders were finished with the city of Worms,<br />

they killed over one thousand Jews in the vicinity<br />

(Williams 42). The Church authorities tried to stop<br />

the crusaders from forcing the Jews to convert and<br />

persecuting them if they refused baptism but were<br />

unsuccessful in aiding them (Phillips & Taylor 47).<br />

While hearing about the forced baptisms,<br />

robberies, and persecutions of the Jewish people in<br />

Cologne and Worms, the Jews in Mainz feared the<br />

peasant army. When they heard the crusaders enter<br />

on May 27th, the Jews in Mainz threw money and<br />

goods into the street so that they would not be<br />

persecuted. Due to the resilience and hatred<br />

towards the Jews, the crusaders removed them from<br />

their homes and murdered them if they refused<br />

baptism into Christianity. The actions from the<br />

crusaders slaughtered over nine hundred Jewish<br />

people in Mainz and the crusaders performed more<br />

1 3

pogroms in Trier, Metz, and Prague. By the end<br />

of the Crusade, over ten thousand Jews were<br />

persecuted by the army of Count Emicho and his<br />

troops. While Peter and his army left the<br />

Rhineland and started to enter Hungary, Count<br />

Emicho and his army wished to carry out attacks<br />

in Hungary (Williams 42). When they were met<br />

with the powerful Hungarian army, they fled<br />

Hungary and Count Emicho turned back and<br />

headed to Swabia (Lambert 78).<br />

While Peter’s army was just leaving the<br />

Rhineland, Walter’s group caught up with them<br />

in Odenberg. As the massive army of people of<br />

all ages and classes collided, they started to get<br />

impatient, hungry, and tired. As they were close<br />

to the Byzantine Empire, Peter the Hermit got<br />

Walter Sans Avoir to lead five thousand others as<br />

an advance group to Belgrade for supplies. When<br />

Walter arrived in Belgrade, the Byzantine was<br />

surprised to see peasants, pilgrims, and minor<br />

nobles coming to fight the Turks. When Walter<br />

and his army asked for food and supplies,<br />

Belgrade was not prepared to give the army<br />

supplies, because it was not harvest season, and<br />

they were not expecting to be a provider to any<br />

army (Williams 43). When Belgrade tells the<br />

advance group that they cannot accommodate<br />

them and deny them entry into the city, the army<br />

immediately gets enraged (Phillips & Taylor 46).<br />

The French crusaders started ravaging the<br />

countryside of Belgrade after the city refused<br />

them entry and passageway into the city. When<br />

Belgrade heard about the violence against their<br />

farmers and the theft in the countryside, they sent<br />

troops to solve the issues. The experienced<br />

Belgrade army captures one hundred and fifty<br />

crusaders and burns them in a church as a<br />

punishment for the destruction of the Belgrade<br />

countryside (Williams 43). While Walter’s advance<br />

army finished receiving some minor setbacks, they<br />

headed for Sofia as Peter’s army reached Nish and<br />

was waiting for Byzantine troop escort to<br />

Constantinople. Peter’s second wave of the Crusade<br />

was also approaching near as they had left Cologne<br />

on April 20th and followed the same route as<br />

Walter Sans Avoir’s army (Phillips & Taylor 46).<br />

As the second wave reached Belgrade, they see the<br />

armour of Walter’s army and panic. The second<br />

wave attacked villagers and came across the<br />

Hungarian Army while doing so (Williams 44). The<br />

second wave performed attacks on the Hungarians<br />

and villagers, and they killed five thousand<br />

Hungarians and four thousand villagers in the<br />

progress. This was the unfortunate first success for<br />

the People’s Crusade, who won but against other<br />

Christians and not against the Turks who they were<br />

hoping to overthrow. The second wave then set the<br />

town on fire and marched on to Nish, where the rest<br />

of the army was waiting (Williams 44; Phillips &<br />

Taylor 46).<br />

The second wave of the People’s Crusade<br />

arrived at Nish on July 3rd after their misadventure<br />

in Belgrade. Peter’s army arrived before them and<br />

managed to convince the garrison commander to let<br />

1 4<br />

The People's Crusade arrives at the gates<br />

ofConstantinople (colourized)

"The<br />

crusaders<br />

were able to<br />

recover"<br />

them through the city and receive an escort to<br />

Constantinople (47). All was going well until the<br />

German crusaders and villagers began fighting<br />

and the Germans set fire to houses and stole<br />

livestock (Williams 44). The garrison<br />

commander, who had already warned the<br />

crusaders to get through the town quickly, sent<br />

the full experienced army of Nish to chase after<br />

the crusaders (Phillips & Taylor 47). The army<br />

quickly attacked the arsonists and thieves, as the<br />

townspeople started to join in. A large amount of<br />

the crusader army was killed, racking up a total<br />

of five thousand crusader deaths and fifteen<br />

thousand villager deaths in Nish (Williams 44).<br />

Fortunately, the crusaders were able to recover<br />

and arrived in Sofia on July 1 2th and awaited<br />

military escorts to Constantinople (Phillips &<br />

Taylor 47).<br />

With escorts from Sofia, the army of the<br />

People’s Crusade arrived in Constantinople on<br />

August 1 st, 1 096. Although there was a<br />

widespread group of people, one-fourth of the<br />

army had been killed or taken into slavery. With<br />

the number of deaths seen during the Crusade,<br />

many people left leaving very few able people to<br />

fight (Williams 44). When Alexius heard the<br />

state of the army, he was in disbelief as he<br />

expected experienced troops. Instead, the army<br />

of peasants expected to be given assistance and<br />

demanded to be fed by the city. After<br />

experiencing the neediness of Peter and his<br />

crusaders, Alexius denied them entrance into the<br />

city and made them camp outside of the walls of<br />

Constantinople (Phillips & Taylor 50). As it was<br />

clear the army was getting impatient in wanting<br />

to go to Jerusalem, Alexius gave the advice that<br />

the army should wait for reinforcements of the<br />

Papal Crusade to take them under their wing, but<br />

Peter would not listen. Even after Alexius had<br />

offered them camp and food outside of<br />

Constantinople, they were hesitant. Instead of<br />

taking up Alexius on his offer, the crusaders<br />

decided to break into Constantinople, steal from the<br />

people and churches, and cause chaos during the<br />

night (Williams 46).<br />

In the morning, Alexius sees the destruction<br />

to Constantinople and sends the crusaders on their<br />

way across the Bosphorus River and into Anatolia<br />

(Williams 47). As they left, Alexius warned them to<br />

stay clear of the Turks for they would wipe out the<br />

whole army of crusaders if they tried to battle them<br />

(Phillips & Taylor 47). As the army entered<br />

Anatolia on August 6th, 1 096, five days after<br />

arriving in Constantinople, some of the crusaders<br />

came across the suburbs of Nicea. The army of<br />

crusaders were running low on supplies; therefore,<br />

the group robbed the suburbs of Nicea and killed<br />

many people in the city. Hoping to create peace,<br />

Alexius sends the crusaders supplies and food to<br />

stop the robberies in Nicea (Williams 47). Instead<br />

of stopping the raids in and around Nicea, the<br />

crusaders rebelled by abusing old people, killing<br />

children, and then roasting them over a fire. The<br />

influence to act so cruelly came from the Italians,<br />

who joined and pillaged towns with the army. The<br />

Italians seemed to help in which they aided in<br />

establishing a camp in Civetot, but due to their<br />

aggression, many fights happened between them<br />

and the crusaders (Phillips & Taylor 50).<br />

After the raids of Nicea, the army of the<br />

People’s Crusade spread and broke up throughout<br />

Anatolia. The main reason for this happening was<br />

due to there being a lack of a powerful leader and<br />

the poor organization of the crusade. Walter and<br />

Peter’s armies split up during the time they would<br />

meet their final battle against the Seljuk Turks<br />

(Madden 37). As a group of mainly German and<br />

Frankish crusaders made their way through<br />

Anatolia, they received word that the Turks were<br />

holding the city of Xerigordon and immediately<br />

went there to fight them (Phillips & Taylor 50).<br />

King Kilij Aslan, the ruler of Anatolia, had heard<br />

about the crusader invasions at Nicea and decided<br />

1 5

to cut off all water and supplies running to Xerigordon. This forced the crusaders to eat and drink their own<br />

blood, urine, and feces due to the lack of supplies. As the Turks heard about an army throughout Anatolia<br />

going to Xerigordon to fight them, the Turkish army immediately arrived expecting a mighty army (Williams<br />

47). When the Turks arrived in Xerigordon, the Turks rapidly started massacring the weak army. After a short<br />

period of eight days, the army of the People’s Crusade, who was originally eager to fight them, hung a white<br />

flag, calling for a truce. After surrendering, the army would have to either convert to Islam, become a martyr,<br />

or become a slave (Phillips & Taylor 50).<br />

In any other battle, the remaining army and back up troops would have returned homeward after<br />

calling a truce. Due to the ignorance of the surviving army that did not receive attacks at Xerigordon, the<br />

Seljuk Turks decided to outwit the rest of the army. The Turks set up spies at the camp in Civetot and spread<br />

the lie that the Germans and Franks had conquered Xerigordon and had taken Nicea as well. The enthusiastic<br />

army quickly headed to Nicea, where they were hoping to share the wealth among each other. The crusaders<br />

were so exhilarated that they went completely unprepared with no armour. During this time, Peter the Hermit<br />

left to go to Constantinople, to negotiate for supplies upon their new wealth of Xerigordon and Nicea.<br />

Fortunately, for Peter the Hermit, he missed the complete end to the People’s Crusade (50).<br />

On October 21 st, 1 096, the crusaders heading to Nicea from Civetot were attacked by the Turkish<br />

army five kilometres away from the camp (50). The Turks showed no mercy while killing infants, monks, and<br />

priests. The weak were slaughtered, and the Turks walked with the rest who could go into slavery. Young<br />

women, supplies, and animals were walked to Nicea, where the women and supplies could be sold (Madden<br />

1 23). After the harsh battle, only three thousand managed to survive the brutality of the Turks out of twenty<br />

thousand people. One of the twenty thousand victims included Walter Sans Avoir, who died while in battle.<br />

The remaining survivors took refuge in a fortress by the sea until they were rescued by the Byzantine army in<br />

Constantinople (Williams 48). Those who made their way back to Constantinople recovered and joined with<br />

other armies following them until the Siege of Antioch (Phillips & Taylor 69). Peter the Hermit, without the<br />

help of Walter Sans Avoir’s military aid, joined the official Crusade and charged the peasant militia, marking<br />

the end of the People’s Crusade (Williams 48).<br />

Secret drawing found in monk manuscripts attached to stories ofthe People's Crusade, some<br />

say the faces ofseveral ofthe monks resemble the writers ofthis magazine!<br />

1 6

The Arrival at<br />

Constantinople<br />

Less than three months after the arrival,<br />

and subsequent speedy departure, of the People’s<br />

Crusade, the city of Constantinople hosted<br />

another group of crusaders, albeit this group<br />

being of a somewhat more professional nature.<br />

The Prince’s Crusade, as the more successful<br />

portion of the First Crusade would come to be<br />

called, was composed mainly of noblemen from<br />

Europe who had heard the cry of “Deus Vult”<br />

from Pope Urban II. This crusade was made up<br />

of five different armies that travelled to<br />

Constantinople separately (Phillips 52), and was<br />

lead by noblemen of various stature and military<br />

experience, unlike the People’s Crusade. The<br />

most prominent among these noblemen, and the<br />

ones who lead the largest contingents of forces,<br />

were Godfrey of Bouillon, Bohemond of<br />

Taranto, Raymond of Toulouse, Duke Robert of<br />

Normandy, and Hugh of Vermandois. Alexios I,<br />

the Byzantine Emperor and the man who had<br />

requested the help of the Western Church against<br />

the Muslims, would have to use manipulation<br />

and flattery to ensure that these Crusaders would<br />

attack their intended targets, and return the<br />

conquered Muslim land back to the Byzantines<br />

(Runciman 93).<br />

Alexios I Comnenus was the Byzantine<br />

Emperor from 1 081 to 111 8. During this time he<br />

would fight wars against both the West, in the<br />

form of the Norman’s in 1 081 -82 (Phillips 38),<br />

and the Seljuk Turks in Anatolia, who had<br />

conquered swathes of Byzantine territory in<br />

Anatolia in the decades prior. He had gained the<br />

throne after a coup against the prior Emperor<br />

Nicephorus III, using his skills of political<br />

espionage to turn the Byzantine aristocracy<br />

against Nicephorus. When the empire of Malik<br />

Shah, ruler of territory spanning from Palestine<br />

Cole Canofari<br />

to Iraq, collapsed following his death in 1 092<br />

(Phillips 38), Alexios would seize the<br />

opportunity and call for help from the West to<br />

take back the former Byzantine holdings in the<br />

East. When the Prince’s Crusade arrived in<br />

Constantinople, Alexios had the memory of the<br />

disastrous People’s Crusade fresh in his mind<br />

and the minds of the people of Constantinople,<br />

and because of this, he was suspicious of the true<br />

motives of the newly arrived Crusaders (Phillips<br />

54). His suspicions were motivated by the reports<br />

of the Crusaders talking openly about capturing<br />

Jerusalem for the Western Christians. This was<br />

worrying to the Alexios as the Byzantines still<br />

laid claim to the city as they were the last<br />

Christian realms to hold it. Bohemond of Taranto<br />

had also been at war with Alexios only a few<br />

short decades earlier along with his father,<br />

Robert Guiscard. Motivated by this, Alexios<br />

decided to ensure that the Crusaders would<br />

return the Byzantine territory by having their<br />

leaders swear an oath to do so upon their armies<br />

arrivals in Constantinople (Runciman 93).<br />

Hugh of Vermandois’ army was the first<br />

to arrive in Constantinople, entering the city in<br />

November of 1 096 (Phillips 52), escorted by a<br />

troop of Byzantines. Hugh was the highest<br />

ranking of the Crusader leaders, as he was the<br />

1 7

1 8<br />

brother of King Philip the First of France,<br />

making him a prince of a prominent royal house<br />

in Europe. Hugh is notable amongst the Crusader<br />

leaders for his massive ego, on account of his<br />

royal birth. Anna Comnena, who was the<br />

daughter of Alexios and had extensively<br />

documented her father's reign, including the<br />

accounts of the Crusaders in Constantinople,<br />

wrote of Hugh sending a letter to Alexios that<br />

showcased his massive ego, “Be advised, O<br />

Emperor, that I am the King of kings, highestranking<br />

of all beneath the sky. My will is that<br />

you should attend me upon my arrival and give<br />

me the magnificent welcome that is fitting for a<br />

visitor of the noblest birth” (Phillips 52). Hugh<br />

travelled to Constantinople through Italy to the<br />

port of Bari on the Adriatic, being joined on the<br />

way by soldiers that had been under the<br />

command of Count Emicho. When he set sail<br />

across the Adriatic, his army became<br />

shipwrecked in what is now Albania and had to<br />

be rescued by the Byzantine governor of the<br />

province (Phillips 52). He was then escorted to<br />

Constantinople by Byzantine troops and arrived<br />

in November of 1 096.<br />

Godfrey of Bouillon’s contingent of the<br />

Crusade was the second army to arrive in<br />

Constantinople in late December of 1 096 (Phillip<br />

52) and camped outside the walls of<br />

Constantinople. Godfrey was accompanied by<br />

his brothers Baldwin and Eustace III, and about<br />

forty thousand soldiers. This army took a similar<br />

route to the People’s Crusade, an idea that might<br />

not have been the best considering the out of<br />

control looting and pillaging that had been done<br />

by the People’s Crusade in the regions they<br />

travelled through. Godfrey marched through<br />

Hungary and then into the Byzantine Empire by<br />

way of Belgrade and then through Sofia and<br />

present-day Edirne to Constantinople.<br />

The third army to arrive in<br />

Constantinople was lead by Bohemond of<br />

Taranto, with his nephew Tancred joining him.<br />

Bohemond is one of the stranger cases of<br />

someone joining the Crusades, as he had just<br />

previously been at war against Alexius on the<br />

side of Bohemond's father, Norman Robert<br />

Guiscard (Phillips 52). Bohemond was not one of<br />

the nobles in attendance at the Council of<br />

Clermont, and therefore was not one of the those<br />

who had uttered the cries of “Deus Vult” following<br />

the speech of Pope Urban II. He had heard about<br />

the Crusade from a group of knights who were<br />

travelling to the Holy Land whilst he was dealing<br />

with a rebellious town in southern Italy. Upon<br />

hearing of the purpose of the crusading knight's<br />

journey, Bohemond decided to take up the cross<br />

and join the Crusade, setting sail for Constantinople<br />

in October of 1 096. They landed in Albania and<br />

then marched the rest of the distance, marching the<br />

rest of the distance to the city, arriving on the 9 of<br />

April 1 097 (Runciman 1 07).<br />

The fourth army that arrived was led by<br />

Raymond of Toulouse, a French nobleman.<br />

Raymond was present at the Council of Clermont<br />

and was one of the first noblemen to join the<br />

crusades following the speech made by Urban the<br />

II. Raymond had experience fighting the Muslims,<br />

as he had taken part in several wars against the<br />

Moors in Spain (Runciman 1 08). Raymond, on<br />

account of his personal experience with Muslims<br />

and military history, was the favourite for the<br />

commander of the lay people of the Crusade and its<br />

military forces (Runciman 11 0). Pope Urban II<br />

wanted to ensure that the Crusade was kept under<br />

spiritual guidance, however, and had made no<br />

concrete promises to Raymond, would appoint the<br />

Bishop of Le Puy, Adhemar, to lead it (Runciman<br />

11 0). Raymond is known for being one of the most<br />

reliable and honest members of the Crusade,

managing to impress even the Byzantines<br />

(Runciman 11 0). His army left for<br />

Constantinople in October of 1 096, and travelled<br />

the overland route through Northern Italy and the<br />

Balkans, arriving in Constantinople on the 21 of<br />

April 1 097.<br />

The fifth army to arrive in the imperial<br />

capital was under the joint command of three<br />

nobles; Robert Duke of Normandy, his brotherin-law<br />

Stephen Count of Blois, and his cousin<br />

Robert the Second Count of Flanders. This army<br />

had its origins in northern France and departed<br />

for the Byzantine capital in October 1 096<br />

(Runciman 11 4). Robert of Normandy, the man<br />

whose forces formed the majority of the fifth<br />

army, was the eldest son of William the<br />

Conqueror. In accordance with his family’s<br />

martial tradition, ever since William’s death,<br />

Robert had been at war with his brother William<br />

Rufus. William Rufus had invaded Normandy<br />

several times, but, following Urban’s speech at<br />

Clermont, Robert had somewhat of a spiritual<br />

epiphany (Runciman 11 4). After this epiphany,<br />

he pledged himself to the service of the Crusade<br />

and the Pope, in return, acted as a mediator<br />

between Robert and his brother, ending their<br />

conflict. Stephen, the Count of Blois, was only<br />

forced into the Crusade by the persistence of his<br />

wife, Adela, the daughter of William the<br />

Conqueror. Among his party was the future<br />

historian Fulcher of Chartres. Robert the Second,<br />

Count of Flanders, was the son of the pious<br />

Robert I, who had made the pilgrimage to<br />

Jerusalem himself in 1 086 (Runciman 11 4). On<br />

the return trip from his pilgrimage, Robert I<br />

enlisted in the army of Alexius for several years<br />

and maintained contact with the Emperor until<br />

his death in 1 093. Because of these personal<br />

connections, both with the Holy Land and the<br />

Byzantine Emperor, it can only be viewed as a<br />

natural step in Roberts life that he takes up the<br />

cross and help out his father's old friend.<br />

Alexius viewed all of these Crusading<br />

army’s with distrust after the misbehaviour of the<br />

People’s Crusade inside Byzantine territory and<br />

knew that he had to get the leaders to swear an<br />

oath of fealty, or at the very least respect, to him<br />

and his property. Alexius was not a simpleton and<br />

knew that while the purpose of the Crusade was<br />

outwardly to protect the vulnerable Christian<br />

pilgrims, the real reason was for the nobles to gain<br />

territory and wealth in the Middle East and did not<br />

object to this, so long as the world recognized who<br />

was the overall sovereign of those lands (Runciman<br />

11 4). Dealing with some of these leaders, such as<br />

Hugh, would prove to be simple affairs, but others,<br />

like Godfrey and Bohemond, would require use<br />

skills of manipulation and cunning, and generous<br />

amounts of gold from the imperial treasury.<br />

Hugh of Vermandois, for all of his demands<br />

for pomp and ceremony and the deference of the<br />

Emperor to him upon his arrival, presented the least<br />

difficult of the Crusaders to convince to swear the<br />

oath of fealty. When Hugh arrived, Alexius dazzled<br />

him with the splendour of the Imperial capital, and<br />

with Alexius’ own wealth. Alexius then showered<br />

gifts of gold and valuables upon Hugh, who went<br />

on to swear the oath of fealty with no hesitation and<br />

was soon spirited across the Bosphorus to Anatolia.<br />

Godfrey would prove to be a much tougher<br />

nut to crack for Alexius. While making his way to<br />

Byzantine territory through the Holy Roman<br />

Empire and Hungary, he had kept tight control over<br />

his army (Runciman 96), declaring that any act of<br />

looting was punishable was death. The initial<br />

journey through Byzantine territory also went<br />

without incident, but as word was received of<br />

Hugh’s pseudo captivity in the capital, Godfrey<br />

grew worried about what was to await him.<br />

Following this, when Godfrey’s army arrived in the<br />

coastal town of Selymbria on the Sea of Marmora,<br />

its long maintained discipline seemed to shatter,and<br />

an 8-day spell of rioting and looting of the<br />

countryside occurred (Runciman 96). This was<br />

excused by Godfrey as retaliation for the captivity<br />

of Hugh, and Alexius responded by sending out<br />

envoys to persuade Godfrey to maintain discipline<br />

and continue his journey in peace. Godfrey<br />

acquiesced, and the army marched towards<br />

Constantinople. Upon its arrival in the city,Alexius<br />

immediately sent out Hugh, who had not yet left, in<br />

order to summon Godfrey to see the Emperor. To<br />

almost everyone's surprise, Godfrey refused the<br />

summons. Godfrey had made contact with the<br />

1 9

20<br />

remnants of the People’s Crusade, who had<br />

blamed its failure on the Empire, and he was<br />

furthermore troubled by Hugh’s attitude, and he<br />

wished to wait and consult with the other leaders<br />

of the Crusading armies before making any<br />

commitments. Alexius was insulted by this and<br />

decided to force Godfrey to come to terms by<br />

cutting off the supplies that were going to his<br />

men from the city. Following this blockade,<br />

Baldwin began raiding the suburbs of the city<br />

almost immediately (Runciman 98). Alexius<br />

relented in his blockade after giving assurances<br />

that Godfrey’s army would be kept supplied so<br />

long as discipline was maintained and it was<br />

moved to Pera, which was a location in which<br />

imperial forces could keep a closer watch on the<br />

activities of the army. This status quo was<br />

maintained for some time (Runciman 99) until<br />

Alexius found out that the other Crusaders were<br />

soon approaching the city. He then decided that<br />

the situation had to be resolved quickly, or he<br />

would find himself with a formidable force of<br />

well-equipped soldiers outside the gates of his<br />

capital, and so began to slowly decrease the<br />

supplies going to the Crusaders. This angered<br />

Godfrey, who assembled his army and began to<br />

attack the gate to the palace quarter of<br />

Constantinople on April 2, the Thursday of Holy<br />

Week. Alexius was shocked by this, as he<br />

considered fighting on such a day to be an insult<br />

against God. As he wished for no bloodshed, he<br />

ordered a number of imperial legions to make a<br />

demonstration, but no attack the Crusaders,<br />

outside of the walls. These legions were to be<br />

covered by archers along the wall, who were<br />

ordered to fire over the Crusaders heads. The<br />

Crusaders, after a brief skirmish that left seven<br />

imperial troops dead (Runciman 1 00), called off<br />

the attack and retired. Alexius sent Hugh out<br />

again, but this only lead Godfrey to insult him<br />

and call him a puppet of the Emperor. Alexius<br />

had grown tired of this struggle and sent out<br />

envoys with the news that he would transport<br />

Godfrey over the Bosphorus without him<br />

swearing the oath, but this attempt was thwarted<br />

when the Crusaders attacked the envoys without<br />

hearing them out first (Runciman 1 00). Alexius<br />

was angry at this point and countered the attack<br />

with some of his most seasoned imperial troops,<br />

who were more than a match for the Crusaders.<br />

After this, Godfrey finally agreed to swear the oath,<br />

along with Baldwin, and after doing so was swiftly<br />

transported across the Bosphorus and away from<br />

Constantinople on Easter Sunday.<br />

Bohemond was the major Crusader leader to<br />

arrive in the city after an uneventful trip through<br />

Byzantine territory, which was the result of his<br />

informing his troops that they were passing through<br />

Christian towns. Bohemond also made sure to keep<br />

strict control of his troops in order to maintain good<br />

relations with the Emperor so that he might be<br />

granted favours down the road from Imperial<br />

sources. When Bohemond arrived in<br />

Constantinople, Alexius immediately recognized<br />

him as the most dangerous of the Crusader leaders.<br />

He had learned from experience of the Normans<br />

prowess in battle, particularly Bohemond’s, and<br />

was warned by his daughter of Bohemond’s skills<br />

in manipulation and his political acumen<br />

(Runciman 1 07) Even though she knew of<br />

Bohemond’s danger, Anna Comnena could not help<br />

but be impressed with his good looks, saying that<br />

he had the physique of a young man, and wrote of<br />

his hairstyle and facial features (Runciman 1 07).<br />

Upon talking to the Emperor, Bohemond<br />

immediately swore the oath, as he knew just how<br />

vital the Byzantines were to the Crusaders’ cause,<br />

and also wished to gain more power as the imperial<br />

legate to the Crusade. After being denied this<br />

position, he was spirited across the Bosphorus by<br />

Alexius on April 9, the same day that Raymond's<br />

force arrived in the city.<br />

Raymond’s journey was fringed with<br />

conflict with the Byzantines, as his army was not<br />

very disciplined and resented the watchful eye of<br />

their imperial escort. Upon arrival at Thrace, which<br />

only a week later had been visited by Bohemond’s<br />

troops, they were dismayed to find there was no<br />

food available. Indignant with this, they began<br />

shouting cries of “Toulouse, Toulouse” (Runciman<br />

111 ) and forced entry into the town, where they<br />

looted houses and markets. Alexius sent an envoy<br />

to Raymond, urging him to come to the capital,<br />

which Raymond obliged. After his departure, his

army grew more restless and continued looting until they were decisively defeated by an imperial garrison<br />

stationed nearby. Raymond was pleased to arrive in Constantinople and asked to see the Emperor at once.<br />

Once he learned of the requirement to swear the oath of fealty to the Emperor, and how it would mean<br />

obeying Bohemond if Bohemond was made imperial legate, Raymond was put off from swearing it. He<br />

refused to swear the oath, saying that God had driven him to come to the Holy Land and therefore God was<br />

his only lord (Runciman 11 3). His other Crusader leaders were dismayed with this and begged him to take the<br />

oath. Raymond eventually relented, but he only agreed to swear a modified version, that promised that<br />

Raymond would respect the life and honour of the Emperor and his property. After this issue was resolved, his<br />

army was transported across the Bosphorus, however, Raymond stayed at the imperial court to talk with<br />

Alexius, who had become a fast friend of Raymonds after Alexius realized that Raymond had no intention of<br />

breaking his oath.<br />

The final army to pass through Constantinople was that of Stephen of Blois and Robert the Second,<br />

and this happened without incident. Stephen would later write of the Emperor's generosity towards himself<br />

and his army. Stephen and Robert swore the oaths almost immediately and were swiftly transported across the<br />

Bosphorus to join the rest of the Crusaders.<br />

Once this was done, Alexius could breathe again without worrying whether the Crusader would decide<br />

to attack their host, and he no longer had to provide food or supplies to them. He had achieved his goal of<br />

having all of the leaders swear the oath of fealty, except for Raymond, but Alexius was still satisfied with the<br />

promise Raymond had made. He fulfilled his desire to have an army come to fight his closest enemies, the<br />

Seljuks in Anatolia. Because of all of this, he was satisfied with what he had done. The Crusaders were happy<br />

as well, as they were one step closer on their road to the Holy Land and on their pilgrimage, but before they<br />

could make it to the Levant, the historic walls of Nicea lay in their path.<br />

21

Don't miss out on next<br />

week's episode of Bayulock<br />

where Bayulock<br />

meets his greatest foe yet,<br />

heresies!<br />

Allanah Hardson is in for some<br />

hardy mysteries in this<br />

brand new season ofBayulock<br />

22<br />

Official sponsor of MNN

Raymond of<br />

Toulouse:<br />

A Profile<br />

Mika Colonia<br />

Raymond IV, better known as the Count<br />

of Toulouse, Raymond of Saint-Gilles, or<br />

Raymond I of Tripoli, was a man of numerous<br />

heroic achievements and great nobility. He was<br />

born approximately 1 041 in southern France to<br />

his mother Almodis, daughter of Bernard, the<br />

Count of the March in Limousin, and his father,<br />

Pons, the Count of Toulouse. He had two other<br />

brothers, William IV of Toulouse and Hugh, and<br />

a sister named Almodis after their mother.<br />

Almodis was Pons’ third wife but she had left<br />

him approximately in 1 051 for Raymond-<br />

Berengar, Count of Barcelona, who became<br />

Almodis’ third husband. Raymond remained with<br />

his father and siblings in France (Hill and Hill 2,<br />

6-7).<br />

Raymond IV had inherited the county of<br />

Toulouse through his bloodline. Frankish in<br />

origin, the House of Toulouse was subject to<br />

Frankish custom, in which property was passed<br />

down from father to eldest son. The men of the<br />

House of Toulouse were powerful nobles<br />

because of their Frankish ancestry. In a time<br />

when there were many political conflicts in the<br />

surrounding nations and when France was<br />

lacking a strong leader, the people depended on<br />

the House of Toulouse and the provincial church<br />

for guidance (Hill and Hill 5-6). When Pons<br />

died, Raymond received one-half of the<br />

bishopric in Nimes, one-half of the abbey in<br />

Saint-Gilles, the castle of Tarascon, and the land<br />

of Argence through his elder brother William,<br />

though Raymond’s property would grow in size<br />

later on by 1 093 when he became the Count of<br />

Painting ofRaymond ofToulouse<br />

Toulouse. It is speculated that Raymond had come<br />

to adopt the title “Count of Saint-Gilles” through<br />

his inheritance of the abbey in Saint-Gilles (7). His<br />

bloodline would make him “southern France’s<br />

richest and most powerful secular lord” during the<br />

First Crusade (Asbridge, The Crusades 35).<br />

The Count of Toulouse was seen as<br />

“commendable in all things, a valiant knight, and a<br />

devout servant of God” (Hill and Hill 4). In his<br />

youth, Raymond was known to be “brighter than<br />

his older brother” and had excelled in combat while<br />

his brother did not (7). The man had strong military<br />

campaign initiatives and had a fierce campaign<br />

against the Moors of Iberia before the First Crusade<br />

(Asbridge, The Crusades 43). But of the given<br />

personality traits, Raymond was well-known for his<br />

piety. Though he may have supported simony prior<br />

to the First Crusade, Raymond supported the<br />

reform of the papacy initiated by Pope Gregory VII<br />

in his later years and was also close allies with<br />

Bishop Adhemar Le Puy, Pope Urban II’s legate,<br />

during the crusade (Hill and Hill 20). Additionally,<br />

he lost one of his eyes while on a pilgrimage to<br />

Jerusalem because he had refused to pay a Muslim<br />

tax on Latin pilgrims (Asbridge, The Crusades 43-<br />

44). Raymond was also known to pray to Saint<br />

Robert, his favourite saint, in times of need, such as<br />

when he prayed for success before setting off for<br />

the First Crusade and when he wanted to know if he<br />

was to inherit the county of Toulouse (Hill and Hill<br />

3, 1 9). These given instances are just a few of many<br />

other illustrations of Raymond’s deep religious<br />

faith.<br />

23

24<br />

While he may have been devout and<br />

praiseworthy, Raymond of Toulouse was a man<br />

of contradicting personalities. Some accounts<br />

remember him as “greedy, superstitious, [or<br />

short-tempered]” (Hill and Hill 4). For many<br />

during the First Crusade, the good qualities about<br />

him were not enough to excuse him from the<br />

thought that he was prideful (Krey 71 ). These<br />

qualities of Raymond were evident during the<br />

First Crusade as he did not get along well with a<br />

number of the crusade leaders. For one, he had<br />

an ongoing feud and struggle for power with<br />

Bohemond of Taranto. Additionally, when<br />

Godfrey of Bouillon became the designated ruler<br />

of Jerusalem after its conquest and ordered<br />

Raymond to leave the Tower of David, Raymond<br />

was especially angry and left Jerusalem for<br />

Jericho (Williams 55, 93).<br />

Raymond also had an affinity for women.<br />

Like his father, he had three wives leading up to<br />

the First Crusade, though his first wife was his<br />

first cousin. His third wife, Elvira, who was the<br />

illegitimate daughter of Spanish king Alfonso VI,<br />

would accompany him on his journey to the Holy<br />

Land (Williams 54-55; Phillips 53). He had a<br />

son, Bertrand, with his second wife Matilda of<br />

Sicily, and another named Alphonse-Jourdain<br />

with Elvira. He was excommunicated twice by<br />

Pope Gregory VII for his first forbidden<br />

marriage. Though he may have liked women<br />

more than he should have, Raymond’s steadfast<br />

devotion to God outshone his promiscuity for he<br />

left his first wife “as a result of the second<br />

excommunication” and would stay faithful to<br />

Elvira, his last wife (Hill and Hill 1 3).<br />

By the time that the First Crusade was<br />

called by Pope Urban II, Raymond was fifty-six.<br />

He was the oldest Crusade leader. Expecting to<br />

die soon due to his age, Raymond had accepted<br />

the pope’s call in order to die in the Holy Land<br />

and was also the first to accept the call (Williams<br />

54; Asbridge, The Crusades 43). This, along with<br />

his piety, meant that he could not swear loyalty<br />

to Byzantine Emperor Alexius unlike the rest of<br />

the crusade leaders as he had already declared<br />

the pope as his overlord. However, Alexius<br />

commended Raymond’s spirituality and allowed<br />

him to swear a modified declaration to respect the<br />

life and goods of the Byzantine Emperor, and this<br />

began a friendship between the two (Williams 59).<br />

Raymond had conquered or established<br />

diplomacy in numerous regions in his route to the<br />

Holy Land. His diplomacy was shown to have its<br />

benefits during the First Crusade. The Muslims at<br />

Ascalon surrendered only to the Count of Toulouse<br />

as a result of him keeping his end of a deal he made<br />

with Iftikhar al-Dawla during the siege of<br />

Jerusalem, which was to let the Fatimid governor<br />

surrender in exchange for treasure and the Tower of<br />

David (Phillips 83). Despite this, Raymond did not<br />

have an established territory outside of his native<br />

land unlike Baldwin of Boulogne, Bohemond, and<br />

Godfrey after the crusade (Hill and Hill 1 43). In his<br />

search for one, the feud between him and<br />

Bohemond that was prominent during the crusade<br />

continued afterwards in the form of territorial<br />

disputes. When he found Bohemond attempting to<br />

claim the port city of Latakia from Byzantine rule<br />

in 1 099, Raymond supposedly challenged and<br />

threatened to attack him if he was not let into the<br />

city. The quarrels posed an obstacle for the Count<br />

of Toulouse in finding an eastern territory to call his<br />

own even though he ultimately took over Latakia<br />