Timbuktu

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

<strong>Timbuktu</strong> and Premodern Traditions of Learning: A Unesco Heritage Site in Danger <br />

Anja-‐Silvia Goeing <br />

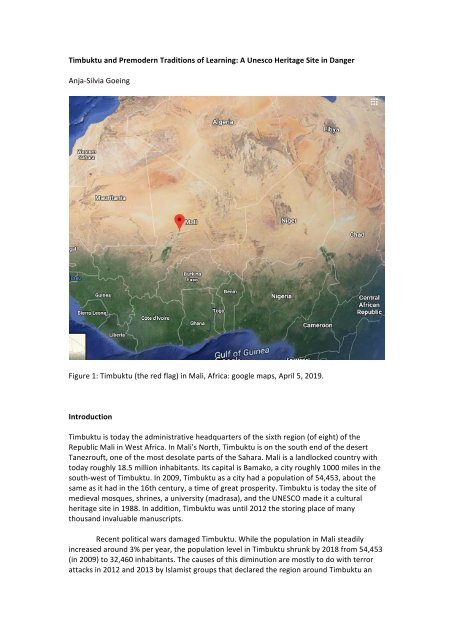

Figure 1: <strong>Timbuktu</strong> (the red flag) in Mali, Africa: google maps, April 5, 2019. <br />

Introduction <br />

<strong>Timbuktu</strong> is today the administrative headquarters of the sixth region (of eight) of the <br />

Republic Mali in West Africa. In Mali's North, <strong>Timbuktu</strong> is on the south end of the desert <br />

Tanezrouft, one of the most desolate parts of the Sahara. Mali is a landlocked country with <br />

today roughly 18.5 million inhabitants. Its capital is Bamako, a city roughly 1000 miles in the <br />

south-‐west of <strong>Timbuktu</strong>. In 2009, <strong>Timbuktu</strong> as a city had a population of 54,453, about the <br />

same as it had in the 16th century, a time of great prosperity. <strong>Timbuktu</strong> is today the site of <br />

medieval mosques, shrines, a university (madrasa), and the UNESCO made it a cultural <br />

heritage site in 1988. In addition, <strong>Timbuktu</strong> was until 2012 the storing place of many <br />

thousand invaluable manuscripts. <br />

Recent political wars damaged <strong>Timbuktu</strong>. While the population in Mali steadily <br />

increased around 3% per year, the population level in <strong>Timbuktu</strong> shrunk by 2018 from 54,453 <br />

(in 2009) to 32,460 inhabitants. The causes of this diminution are mostly to do with terror <br />

attacks in 2012 and 2013 by Islamist groups that declared the region around <strong>Timbuktu</strong> an

independent state, which led to people fleeing the region. The political situation stabilized <br />

again, when on April 1, 2013, French warplanes helped Malian ground forces chase the <br />

remaining rebels out of the city center. But the Islamists had destroyed 14 centuries-‐old <br />

shrines of local Sufi saints of the 16 that UNESCO had put under their protection, and they <br />

had set fire to the Ahmad-‐Baba-‐Library, the then home of multiple-‐thousand invaluable <br />

Islamic manuscripts from medieval times and later. According to the Hamburg Centre for the <br />

Study of Manuscript culture, about 95% of the manuscripts from Ahmad-‐Baba-‐Library and <br />

many private libraries in <strong>Timbuktu</strong> could be rehoused in the State Capital Bamako, and the <br />

Hamburg Centre gives their count in 2015 as 285.000 individual items. <br />

Figure 2: Niger-‐Saharan Medieval Trade Routes around 1400: <strong>Timbuktu</strong> is Located on the <br />

crossroads between North, South, East and West. <br />

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Niger_saharan_medieval_trade_routes.PNG <br />

(accessed April 5, 2019) <br />

<strong>Timbuktu</strong>'s rich history of learning had to do with its situation as a commercial hub <br />

from the 12th century. It was at the cross-‐roads of trans-‐Saharan trade routes and became <br />

famous for its supply of gold. The city attracted Muslim scholars and scribes from different <br />

Islamic beliefs and different geographical regions. Many of them brought manuscripts with <br />

them and copied other manuscripts while in <strong>Timbuktu</strong>. Their time of greatest affluence were <br />

the 15th and 16th centuries. Many legends about <strong>Timbuktu</strong> were brought to Europe, and <br />

the 19th century saw the French colonization of the place in 1893. In 1960, the independent <br />

Republic of Mali was established. Today, Mali is one of the poorest countries in the world, it <br />

ranks no. 182 in 2017 on the Human Development Index. In addition, <strong>Timbuktu</strong>, bordering <br />

the desert, suffers from the danger of desertification.

Figure 3: Location of the three mosques in the city centre: Plan of <strong>Timbuktu</strong>, made by the <br />

Africa explorer Dr. Heinrich Barth in 1855, <br />

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Plan_von_<strong>Timbuktu</strong>_1855.jpg. Source: <br />

Mittheilungen aus Justus Perthes’ Geographischer Anstalt über Wichtige Neue <br />

Erforschungen auf dem Gesammtgebiete der Geographie von Dr. A. Petermann. Teil 1, 1855 <br />

Three mosques, of which the two oldest original buildings go back to the early 14th <br />

century, the Djingareyber Mosque and the Sankore Mosque that included a university, and <br />

the Sidi Yahia Mosque (from 1400), together with sixteen mausoleums and holy public <br />

places make up the most important heritage spaces in <strong>Timbuktu</strong>. The mosques were rebuilt <br />

and restored in the late 16th century, between 1570 and 1583 (Djingareyber), 1577-‐1578 <br />

(Sidi Yahia), and 1578-‐1582 (Sankore). I am interested in linking the manuscripts back to the <br />

centre of learning at the Sankore madrasa, or university, and I would like to point to the <br />

intangible world heritage behind the tangible buildings and manuscripts: What were these <br />

manuscript cultures exactly? And how can they be preserved? <br />

Values of <strong>Timbuktu</strong>'s Cultural Heritage <br />

The urban space containing the three mosques and 16 mausoleums has outstanding <br />

value as a testimony of historical, architectural, and urban development in a region of the <br />

Subsahara that does not present many relics of the past. Additionally to the UNESCO <br />

valuation that is solely geared towards the buildings, the 285.000 manuscripts (still today <br />

mostly in private possession) have not only tangible, but also intangible value to point to a <br />

long tradition of Islamic scholarship and learning, and of manuscript and scribal culture from <br />

1200 to today.

For a historian, the fact that the mosques and other holy places of <strong>Timbuktu</strong> have been <br />

recorded from the late sixteenth century in the Arabic chronicles, or "tarikhs" of <strong>Timbuktu</strong>, <br />

make the buildings as visualizing component and thus as speaking relics of this past even <br />

more valuable. The Arabic chronicles record <strong>Timbuktu</strong> as a centre of West African Sudan <br />

market and scribal culture. Because <strong>Timbuktu</strong> was at the crossroads of trade routes, the <br />

mosques and holy places of <strong>Timbuktu</strong> were imperative for the development and spread of <br />

Islam in Africa in late medieval and early modern times. <br />

Figure 4: Sankore Mosque, <strong>Timbuktu</strong>. Photo Francesco Bandarin, date 01/02/2005; <br />

https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/119/gallery/&index=1&maxrows=12 (accessed April 5, 2019) <br />

The buildings are architectural highlights from an era of great prosperity and intellectual <br />

importance. The three mosques present a specific style of architecture, working with <br />

earthen materials. Buildings as old as the mosques from these materials are very rare, but in <br />

this case they also represent a high point of Islamic learning and cultural and trade exchange <br />

of this region. How they were restored in the 16th century, which materials were used, how <br />

the spaces within and outside the mosques were configured, can tell us about West African <br />

Sudan architectural development, of which <strong>Timbuktu</strong> was the capital of culture in the 15th <br />

and 16th century, the time when the mosques were restored. <br />

As Elias Saad (Saad, p. 108) points out, the topography and thus, the urban space of <br />

<strong>Timbuktu</strong> has always been dominated by its mosques: "Their architecture rose above <br />

everything else in the city and they became the main points of referral and congregation in <br />

their respective quarters." They served not only as centres for prayers, but also as charities <br />

and hospitals for the poor. Saad assumes that the mosques determined the directions in

delineation of quarters. For <strong>Timbuktu</strong>, the mosques had therefore also value as referrals for <br />

urban planning. With their central situation and integrating tasks, the mosques were the <br />

main forums of interaction between the various ethnical and social groups of the city, and <br />

their mixing with marketeers, travellers, migrating scholars. <br />

Figure 5: United Nations Photo: MINUSMA Support in the Preservation of Ancient <br />

Manuscripts in Mali, photo taken January 5, 2016: <br />

https://www.flickr.com/photos/un_photo/30874616233/in/photolist-‐qKptM-‐DCbuxe-‐<br />

6okCEy-‐83QteH-‐6okCp7-‐6okCA1-‐6okCgq-‐6ogrit-‐6okC2s-‐6ogrvH-‐6okCdb-‐rYees9-‐P3htKx <br />

The city of <strong>Timbuktu</strong> has developed since the 16th century, and is now situated in one of <br />

the poorest regions of the world, as I have explained above. To keep a tradition alive that <br />

speaks about its prosperous past, is necessary to retain the value of the place and the <br />

unique features of its history and greatness. But the tradition has been kept alive, outside <br />

the valuable efforts of UNESCO. The old families of <strong>Timbuktu</strong> keep as one of the most <br />

treasured possessions folders with manuscripts that their ancestors copied from lectures <br />

and textbooks given at the Sankore University (madrasa) and in the culture of learning that <br />

surrounded it. Some of these manuscripts are very old and stem from the 14th century. An <br />

initiative of <strong>Timbuktu</strong> citizens together with money from South Africa, the Mellon <br />

foundation and other foundations worked to make these treasure visible to the public and <br />

at the same time to put them into storage places more adapted to their state of fragility. <br />

UNESCO officially complained about the site of the Ahmad-‐Baba-‐Museum next to the <br />

Sankore mosque over many years. And the complaints only ceased with the Islamist burning <br />

of the Museum in 2012. Although the manuscripts could be rescued through night-‐drives of <br />

single people to Bamako, the capital of Mali, the collections did not yet get the recognition <br />

as tangible and intangible heritage from UNESCO that they should have had. Today, the <br />

manuscripts are curated by a team from Hamburg University in Germany with the help of <br />

the German Federal Foreign Office Ministry, the German Jutta Vogel Foundation and the <br />

German Gerda Henckel Foundation.

The key question and task here is to put the two strings together again, the manuscript <br />

culture and the building culture and show more about the scholars and their habits of <br />

learning, writing and talking in the spaces of the city and with the other social groups mixing <br />

on the markets and in the mosques. I want to know how it is that all the old families of <br />

<strong>Timbuktu</strong> were able to take part in this writing cultures, and how it is that manuscripts came <br />

to and were distributed from <strong>Timbuktu</strong> in olden times. The texts, as well as the buildings, <br />

together with the history of the houses as storing places, might give answers to these <br />

questions, also the stories that families were passing on to their children about the <br />

manuscripts and how they came to possess and cherish them. <br />

<strong>Timbuktu</strong>'s Cultural Heritage conserved, utilized, and managed <br />

Figure 6: Islamists set fire to sacred tombs in <strong>Timbuktu</strong>: Islamist militants destroy an ancient <br />

shrine in <strong>Timbuktu</strong> on July 1, 2012 in a still from a video. <br />

https://www.cnn.com/2012/06/30/world/africa/mali-‐shrine-‐attack/index.html (accessed: <br />

April 5, 2019) <br />

There have been two stages of conservation: The first stage started when in 1988 <br />

UNESCO accepted the three mosques and 16 mausoleums of <strong>Timbuktu</strong> as Cultural Heritage. <br />

It ended, when in 2012 an islamic war over <strong>Timbuktu</strong> broke out, with 20.000 people leaving <br />

the city, cultural heritage was destroyed, and about 95% of the old manuscript were brought <br />

to safety in temporal spaces in Bamako, the capital of Mali. The second phase of <br />

conservation started immediately after the war. However, although the war was won by <br />

Malian forces with the help of French military in March 2013, up to today, the city is still a <br />

place of military presence, and most of the manuscripts have not been returned to their old <br />

home. The center space with the three mosques is intact, with fourteen of the sixteen <br />

mausoleums destroyed and re-‐built again after 2014, and tourism is almost non-‐existent <br />

because of war threat that is still imminent in the region. <br />

The UNESCO documents publicly available but tucked away on the UNESCO World <br />

Heritage Site are my chief source for summarizing the efforts of conservation, utilization and

management of the building site before and after the war. The manuscripts, however, have <br />

their own narrative which is not so widely documented, because they had not been part of <br />

the UNESCO World Heritage Site. But the website of the manuscripts' remote curatorial <br />

place at the University of Hamburg gives some indications what has been done with them <br />

and how they are managed. <br />

1. Before the war <br />

Conservation, utilisation and management of the World Heritage Site before the war <br />

was directed first and foremost to get the site out of danger created by the climate. Since <br />

1990 until 2005, UNESCO had put the <strong>Timbuktu</strong> site on their list of World Heritage in danger: <br />

the report of 1996 states that "the Mosques of <strong>Timbuktu</strong> are made of fragile materials which <br />

are regularly threatened by rare but violent bad weather and have only survived several <br />

centuries due to the annual maintenance carried out by the local population, under the <br />

direction of the Imman and the responsibility of the corporation of masons, and with <br />

funding from the wealthy personalities of the town for the more costly works." Both <br />

negligence by UNESCO, and also its over-‐ambition could threaten the local traditions and <br />

lead to the destruction of the mosques. <br />

A workshop in 1996 was able to connect the international UNESCO conservation teams <br />

with the local groups and their imam. The workshop had the goal to show to the UNESCO <br />

officials the old techniques of conservation and was the basis of a future conservation plan <br />

for the site. (https://whc.UNESCO.org/en/soc/2113). In 2003, the UNESCO report on <br />

<strong>Timbuktu</strong> was very positive, declaring that the danger issues such as sand encroachment, <br />

lack of financial resources, deterioration of the rainwater drainage syste and the need for <br />

appropriate law have all been resolved. (https://whc.UNESCO.org/en/soc/2680) In 2005, the <br />

heritage site was taken off the UNESCO List of World Heritage in Danger, after a <br />

Governmental conservation heritage plan had been accepted. <br />

(https://whc.UNESCO.org/en/soc/1243) <br />

UNESCO officials complained in later reports up to 2012 that the state allowed the <br />

Ahmad-‐Baba-‐Museum, a new building of the 1974 created Ahmad Baba Institute of Higher <br />

Learning and Islamic Research to be build in the direct vicinity of the Sankore mosque, thus <br />

changing the surroundings of the mosque from their original structure. It is here that a <br />

general city heritage management plan would have been of advantage to connect <br />

stakeholders with interest in the buildin site with those with interest in the manuscripts and <br />

scholarship (displayed by the Ahmad-‐Baba-‐Museum), wich however did not exist. <br />

(https://whc.UNESCO.org/en/soc/1161) The interests of UNESCO were overwritten by the <br />

interests of the Presidents of Mali and South Africa to build the Ahmad-‐Baba-‐Museum <br />

directly on the old university site at the Sankore mosque to house and display the old <br />

manuscripts, and for welcoming researchers worldwide. (This is the first time that the <br />

reports mentioning attention to tourism and utilization of the site, however with a critical <br />

undertone!)

Figure 7: Rehabilitation of the mausoleums in <strong>Timbuktu</strong> destroyed by jihadists during the <br />

occupation of the northern regions of Mali. Program Implemented by UNESCO and its <br />

partners as the Minister of Culture of Mali and MINUSMA. <strong>Timbuktu</strong>, April 15, 2015. Photo: <br />

MINUSMA/Harandane. https://www.flickr.com/photos/minusma/17389128385 (accessed: <br />

April 5, 2019) <br />

2. After the war <br />

All strategies that had been used before the attack by UNESCO and other sponsors such <br />

as the Mellon foundation were geared towards making the heritage publicly accessible. In <br />

and after the war, from 2012, the strategies were much more about keeping the manuscript <br />

storing places a secret and not put too much public attention on the armed conflicts. <br />

UNESCO inscribed the <strong>Timbuktu</strong> Heritage Site yet again in their List of World Heritage in <br />

Danger, this time danger of destruction through occupation of the site by armed groups, <br />

absence of management, and the destructions of the mausoleums that had already <br />

happened. (https://whc.UNESCO.org/en/soc/1865). <strong>Timbuktu</strong> suffered another armed <br />

conflict, with the destruction of 15 of the 16 mausoleums , as reported on 18 February 2015 <br />

by the State Party. <br />

Different from before the war and very fortunately for the site, this time national and <br />

international sponsors pulled together to work on restoration and reconstruction strategies. <br />

(https://whc.UNESCO.org/en/soc/3218). And the state of deterioration created now for <br />

the first time a collaboration offered by UNESCO to rehabilitate four private ancient <br />

manuscripts libraries (that were in existence before the war, but never mentioned). In 2016, <br />

fourteen of the 16 mausoleums were rebuilt, and several of the private libraries restored. <br />

The most recent report of 2018 was very positive: most of the war damage could be <br />

restored, and the local, state and UNESCO officials were finally able to put a 2018-‐2022 <br />

Management and Conservation Plan in action, a meta-‐plan for the whole of <strong>Timbuktu</strong> and its <br />

heritage. We note that in the face of war, they have learned to work together. The Ahmed <br />

Baba Heritage Institute and its many manuscripts is included in this new collaboration. While

the secondary literature consulted does not give hope for the manuscripts ever returning to <br />

<strong>Timbuktu</strong>, the UNESCO report of 2018 opens up this new window and we will definitely stay <br />

tuned to know what of the management and conservation plan will have been realised over <br />

the next couple of years, seeing the continuing unstable security situation and the notable <br />

impacts due to military presence in <strong>Timbuktu</strong>. <br />

Bibliography <br />

Centre for the Study of Manuscript Culture, University of Hamburg: <br />

https://www.manuscript-‐cultures.uni-‐hamburg.de/timbuktu/timbuktu_e.html (March 28, <br />

2019) <br />

English, Charlie: The Storied City: The Quest for <strong>Timbuktu</strong> and the Fantastic Mission to save <br />

its Past. New York: Riverhead Books, 2017 <br />

Human Development Index: http://hdr.undp.org/en/data (March 28, 2019) <br />

Hunwick, J.O., “<strong>Timbuktu</strong>”, in: Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Edited by: P. <br />

Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. Consulted online on 24 <br />

March 2019 ; First published online: 2012; First print edition: ISBN: <br />

9789004161214, 1960-‐2007. <br />

Saad, Elias N.: Social history of <strong>Timbuktu</strong>: the role of Muslim scholars and notables 1400-‐<br />

1900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983 <br />

Unesco World Heritage: <strong>Timbuktu</strong>. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/119 (March 27, 2019) <br />

UNESCO World Heritage Centre-‐State of Conservation: <strong>Timbuktu</strong> (Mali) 1990: <br />

https://whc.UNESCO.org/en/soc/1619 (accessed: April 5, 2019) <br />

UNESCO World Heritage Centre-‐State of Conservation: <strong>Timbuktu</strong> (Mali) 1994: <br />

https://whc.UNESCO.org/en/soc/1800 (accessed: April 5, 2019) <br />

UNESCO World Heritage Centre-‐State of Conservation: <strong>Timbuktu</strong> (Mali) 1995: <br />

https://whc.UNESCO.org/en/soc/2019 (accessed: April 5, 2019) <br />

UNESCO World Heritage Centre-‐State of Conservation: <strong>Timbuktu</strong> (Mali) 1997: <br />

https://whc.UNESCO.org/en/soc/2113 (accessed: April 5, 2019) <br />

UNESCO World Heritage Centre-‐State of Conservation: <strong>Timbuktu</strong> (Mali) 2003: <br />

https://whc.UNESCO.org/en/soc/2680 (accessed: April 5, 2019) <br />

UNESCO World Heritage Centre-‐State of Conservation: <strong>Timbuktu</strong> (Mali) 2004: <br />

https://whc.UNESCO.org/en/soc/1376 (accessed: April 5, 2019) <br />

UNESCO World Heritage Centre-‐State of Conservation: <strong>Timbuktu</strong> (Mali) 2005: <br />

https://whc.UNESCO.org/en/soc/1243 (accessed: April 5, 2019) <br />

UNESCO World Heritage Centre-‐State of Conservation: <strong>Timbuktu</strong> (Mali) 2006: <br />

https://whc.UNESCO.org/en/soc/1161 (accessed: April 5, 2019) <br />

UNESCO World Heritage Centre-‐State of Conservation: <strong>Timbuktu</strong> (Mali) 2007: <br />

https://whc.UNESCO.org/en/soc/1004 (accessed: April 5, 2019) <br />

UNESCO World Heritage Centre-‐State of Conservation: <strong>Timbuktu</strong> (Mali) 2008: <br />

https://whc.UNESCO.org/en/soc/928 (accessed: April 5, 2019) <br />

UNESCO World Heritage Centre-‐State of Conservation: <strong>Timbuktu</strong> (Mali) 2009: <br />

https://whc.UNESCO.org/en/soc/747 (accessed: April 5, 2019)

UNESCO World Heritage Centre-‐State of Conservation: <strong>Timbuktu</strong> (Mali) 2010: <br />

https://whc.UNESCO.org/en/soc/502 (accessed: April 5, 2019) <br />

UNESCO World Heritage Centre-‐State of Conservation: <strong>Timbuktu</strong> (Mali) 2011: <br />

https://whc.UNESCO.org/en/soc/382 (accessed: April 5, 2019) <br />

UNESCO World Heritage Centre-‐State of Conservation: <strong>Timbuktu</strong> (Mali) 2012: <br />

https://whc.UNESCO.org/en/soc/261 (accessed: April 5, 2019) <br />

UNESCO World Heritage Centre-‐State of Conservation: <strong>Timbuktu</strong> (Mali) 2013: <br />

https://whc.UNESCO.org/en/soc/1865 (accessed: April 5, 2019) <br />

UNESCO World Heritage Centre-‐State of Conservation: <strong>Timbuktu</strong> (Mali) 2014: <br />

https://whc.UNESCO.org/en/soc/2928 (accessed: April 5, 2019) <br />

UNESCO World Heritage Centre-‐State of Conservation: <strong>Timbuktu</strong> (Mali) 2015: <br />

https://whc.UNESCO.org/en/soc/3218 (accessed: April 5, 2019) <br />

UNESCO World Heritage Centre-‐State of Conservation: <strong>Timbuktu</strong> (Mali) 2016: <br />

https://whc.UNESCO.org/en/soc/3335 (accessed: April 5, 2019) <br />

UNESCO World Heritage Centre-‐State of Conservation: <strong>Timbuktu</strong> (Mali) 2017: <br />

https://whc.UNESCO.org/en/soc/2113 (accessed: April 5, 2019) <br />

UNESCO World Heritage Centre-‐State of Conservation: <strong>Timbuktu</strong> (Mali) 2018: <br />

https://whc.UNESCO.org/en/soc/3779 (accessed: April 5, 2019)