Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Towards a Democratic Greenspace: A Sociohistorical Perspective on the Public Park From Ancient Rome to Modern Seattle Andrea <strong>Masterson</strong> Spring 2019<br />

Towards a Democratic<br />

Greenspace:<br />

A Sociohistorical Perspective on the Public Park<br />

From Ancient Rome to Modern Seattle<br />

Andrea <strong>Masterson</strong>

Towards a Democratic<br />

Greenspace:<br />

A Sociohistorical Perspective on the Public Park<br />

From Ancient Rome to Modern Seattle<br />

Andrea <strong>Masterson</strong>

Towards a Democratic Greenspace:<br />

A Sociohistorical Perspective on the Public Park<br />

From Ancient Rome to Modern Seattle<br />

A Senior Essay in Architecture<br />

Andrea <strong>Masterson</strong><br />

Spring 2019<br />

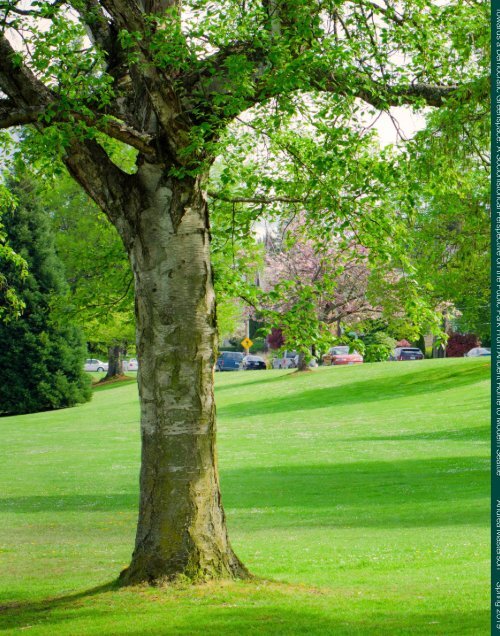

Cover image: Green Lake Park, Seattle. Image used under license from istockphoto.com<br />

Endsheets: Planting Plan for Volunteer Park. Olmsted Brothers. "Volunteer Park Seattle,<br />

WA Planting Plan." Map. February 16, 1910. Job #02695. Seattle Municipal Archives.<br />

Epigram: Curtis, George William. "Editor's Easy Chair." Harper's New Monthly Magazine<br />

11, (June-November 1855): 125.

“A Park is not for those who can go to the country, but for those who cannot. It is a civic<br />

Newport, and Berkshire, and White Hills. It is fresh air for those who cannot go to the seaside;<br />

and green leaves, and silence, and the signing of birds, for those who cannot fly to the<br />

mountains. It is a fountain of health for the whole city.”<br />

-George William Curtis

Acknowledgements<br />

First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor, Bryan Fuermann, who proved<br />

encyclopedic in his knowledge of European landscape history and connected me with countless<br />

sources along the way. His exactitude and patience made working with him an absolute pleasure.<br />

Marta Caldeira, my Senior Research Colloquium Professor, taught me how to frame such<br />

an ambitious project, and directed my research throughout. DUS Bimal Mendis has worked<br />

tirelessly to improve the urban studies program at Yale, and future generations of Yale students<br />

have the opportunity to major in urban studies as a result. Rosalie Bernardi, the unsung hero of<br />

YSOA, makes the entire department function smoothly and efficiently. Dean Ferando and Head<br />

Saltzman of Jonathan Edwards College provided me with a generous Richter Fellowship, which<br />

allowed me to conduct my research on the Seattle parks system. The Librarians at the Seattle<br />

Central Library proved tremendously helpful, and I have the wealth of resources available<br />

through Yale University Library and the Seattle Public Library, in addition to the Seattle<br />

Municipal Archives to thank for many of my sources.<br />

My urban studies classmates Andy and Mary Catherine provided four years of moral<br />

support, invigorating discussions, and much-needed perspectives on the role that urban studies<br />

plays in the field of architecture and within the architecture major at Yale. I thank them for<br />

refusing to be overlooked and striving to give urban studies at Yale the attention it deserves.<br />

My beloved New Haven has provided a home, an education, and a field study for the past<br />

four years. It is the reason I chose to study architecture, and the reason I will always feel that I<br />

have a home on the east coast.<br />

Yale Track and Field has taught me the value of patience, commitment, and having a<br />

level perspective. I am indebted to my teammates, who are my closest friends and constant<br />

support system. My coach, Amy Gosztyla, has made countless opportunities possible in my time<br />

at Yale, and has always had the utmost faith in my abilities.<br />

My best friend, Arvind, has been my number one ally through my four years at Yale. I<br />

have grown the most because of him, and I have learned an incredible amount just from<br />

watching him strive to always do better.<br />

My parents, Mark and Wanda and my brother, Brian are my team and the center of my<br />

universe. The love and support that I receive from them and try give in return means the world to<br />

me. They are the reason that Seattle will always be home, and why I want to do what I can to<br />

make it a better place.<br />

Finally, to Aunt Mary, thank you for instilling in me a love of our parks, the outdoors,<br />

and the city that we call home. I will always treasure your stories of your days on the trails of the<br />

Cascades, as an athlete in the days before competitive sports were available to women, or as a<br />

trailblazer in the Seattle community. You have taught me to find beauty in the world around me,<br />

and to appreciate every opportunity that comes my way.

Table of Contents<br />

Introduction………..………...………………………………………………………………………………………..2<br />

Section 1–History of the Public Park in Ancient Rome.….…...…………..……………….…………...7<br />

The Domus Aurea………………..….…………..…….……………....…………………..……10<br />

Baroque Parks in 17 th Century Rome…...………………..…...………...……………………...14<br />

The Villa Borghese…...……….....…………………..…………….…...……………………....16<br />

Hunt’s Three Natures and the Villa Borghese....…………………………...…...……………...19<br />

Section 2—English Park Design in 16th-19th Century London...……...…………………………….23<br />

Public Patronage of Peri-urban Fields.....……….……………………………………………...23<br />

Town Gardens and Square Gardens...……………...…….…………………………………….24<br />

Rus in Urbe in the London Square....…...………………..……...……………………………..32<br />

The Rise of Public Parks in Victorian London...…………...….……………………………....34<br />

The Royal Parks of London ….………………..………...…………………………………….35<br />

The Serpentine…....………………..…………………………………………………………..38<br />

Making a Case for Public Parks: The Public Health Movement…...………………....……….41<br />

Frederick Law Olmsted and Birkenhead Park: Bringing the English Park to America......…...43<br />

Section 3—The Roots of the American Parks System…………....………….………………………..46<br />

The London Square and Early Park Planning in America….......….……………….………….46<br />

Rural Cemeteries and Transforming Attitudes toward Public Space in 19 th Century<br />

America........…………………………………………………………………………………...52<br />

Frederick Law Olmsted and Central Park..………………..…………………………………..54<br />

Prospect Park…..……………….....…………………………..……………………………….61<br />

Section 4—The Formation of Seattle’s Public Parks System...………………………………………66<br />

John Charles Olmsted...................................…………...……………………………………...68<br />

First Annual Report of the Board of Parks Commissioners for Seattle, 1903.......….......…….69<br />

Woodland, Green Lake, and Ravenna Parks...…...…….....…………………………………...78<br />

The Three Natures Redux…...………...…………..…………………………………………..86<br />

Volunteer Park......………………………………….…………………………………...…….87<br />

Conclusion…..…………………………………….………………………………………………………………….94<br />

Appendix I: Works Cited..……...…………………...………………..…………………………………………...106<br />

Appendix II: Index of Images.....………………………………….………………………………………………112<br />

1

Introduction<br />

In 1859, the thirty-seven-year-old Frederick Law Olmsted was in the midst of carrying<br />

out his first commission as a landscape architect. It was a toilsome process, which required<br />

developing a run-down tract of Manhattan Island bedrock and man-made refuse into a vast and<br />

idyllic park. Just two years before, he had grumbled, “a suburb more filthy, squalid, and<br />

disgusting can hardly be imagined.” 1 It was impossible for him to know at the time that the<br />

construction of this park would serve as the launching point for a storied career that would<br />

establish him as the preeminent landscape architect of the nineteenth century. As the<br />

Superintendent and Architect-in-Chief of Central Park, Olmsted was responsible for overseeing<br />

its development, and ensuring that it would be laid out according to his vision. Though there was<br />

no way of ensuring its success, the park that Olmsted and his partner, Calvert Vaux had<br />

envisioned in their competition-winning Greensward plan, if executed properly, had the potential<br />

to be the most significant park in the city of New York and the United States, on par with the<br />

most exquisite parks in England and Western Europe. Most of all, it would be a park, as the<br />

architect wrote during that trying period, for “those who have no means to go into the country for<br />

relief from the heat and turmoil of the city.” 2 In an 1858 letter to the New York Park<br />

Commissioners, Olmsted described the chief objective of the park as to provide a space of refuge<br />

for all, writing, “it is one great purpose of the Park to supply to the hundreds of thousands of<br />

tired workers, who have no opportunity to spend their summers in the country, a specimen of<br />

God's handiwork that shall be to them, inexpensively, what a month or two in the White<br />

1<br />

Olmsted, F. L. and Calvert Vaux, “Greensward.” In The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted: Vol III: Creating<br />

Central Park 1857-1861. Edited by Beveridge, Charles E. and David Schuyler. Baltimore: John Hopkins University<br />

Press, 1983, 205.<br />

2<br />

Olmsted, Frederick Law. Letter, 1859.<br />

2

Mountains or the Adirondacks is, at great cost, to those in easier circumstances.” 3 Though it took<br />

on the visual trappings of an English pleasure park, the park that Olmsted eventually produced<br />

successfully subverted expectations for the use of the space, taking a design that had been<br />

originally laid out for Royal enjoyment and transforming it into one that was made available to<br />

the most humble laborer. The extent to which this Olmstedian democratic vision for public<br />

greenspace has been carried into the present day is the subject of this study, and its ultimate<br />

efficacy remains to be assessed.<br />

Public parks are a versatile tool in urban planning, with ranging benefits, from improving<br />

public health (Godbey, 1998; Ho, 2003; Kruger, 2008) to perceived levels of wellbeing, in<br />

addition to providing space for leisure, physical activity (Godbey, 1983; CDC) and escape from<br />

the crowding and constraints of the city. 4 These advantages are felt across age (Godbey et al.<br />

1983; CDC, 1997), race (Tinsley et al. 2002), and socioeconomic groupings (Payne et al. 2002). 5<br />

Parks provide important stages for youth, from stages for social display (the skate park) to stages<br />

for achievement and competition (the athletic field). However, these spaces, while public, cannot<br />

immediately be understood to be democratic; their urban histories reveal that they were designed<br />

to prioritize certain groups, and were geographically distributed without considerations of access<br />

3<br />

Olmsted, Frederick Law. Letter to Board of the Commissioners of the Central Park, May 31, 1858.<br />

4<br />

Godbey, G., Roy, M., Payne, L., & Orsega-Smith, E. “The Relation between Health and Use of Local Parks.”<br />

National Recreation Foundation, 1998.<br />

Ho, Ching-Hua, Laura Payne, Elizabeth Orsega-Smith, and Geoffrey Godbey. “Parks, Recreation and Public<br />

Health.” Parks & Recreation 38, no. 4 (2003): 18.<br />

Kruger, Judy. “Parks, Recreation, and Public Health Collaborative.” Environmental Health Insights vol. 2 (3 Dec.<br />

2008): 123-5.<br />

5<br />

Godbey, G., & Blazey, M. “Old People in Urban Parks: An Exploratory Investigation.” Journal of Leisure<br />

Research 15, no. 3 (1983): 229–244.<br />

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Guidelines for School and community Programs to Promote Lifelong<br />

Physical Activity among Young People.” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 46 (1997): 1-36.<br />

Tinsley, H. E. A., Tinsley, D. J., & Croskeys, C. E. “Park Usage, Social Milieu, and Psychological Benefits of<br />

Park Use Reported by Older Urban Park Users from Four Ethnic Groups.” Leisure Sciences 24, (2002):<br />

199-218.<br />

Payne, L. L., Mowen, A. J., & Orsega-Smith, E. “An Examination of Park Preferences and Behaviors Among<br />

Urban Residents: The Role of Residential Location, Race, and Age.” Leisure Sciences 24, no. 2 (2002): 181–198.<br />

3

to all. As such, while public parks may be equitable in name, they are nonetheless spaces of<br />

exclusion—prioritizing the able-bodied and those in proximity to their resources, for instance, or<br />

those who have access to transportation and leisure time (Scott et al. 1994). 6 Studies show<br />

decreasing rates of physical activity with increasing age for minority and low-income youth<br />

(Gordon-Larsen et al, 2000), and lower rates of vigorous exercise among youth with less parental<br />

support and less education on the benefits of physical exercise (Zakarian et al. 1994). 7<br />

Furthermore, urban patterns of physical activity and park use demonstrate that there are many<br />

social and environmental barriers to participation in organized sports, exercise, and access to<br />

community park resources (Scott et al, 1994). In order to better understand how public<br />

greenspaces and these conditions of unequal access came to exist, it is necessary to first examine<br />

the historical context in which today’s public parks were produced. This project sets out to study<br />

how history has produced uneven conditions of accessibility and equity in public parks, in order<br />

to understand how cities serve diverse, heterogeneous populations, or fail to do so.<br />

Seattle provides an important case study on the changing public nature of parks. In 1903,<br />

John Charles Olmsted’s master plan for Seattle sought, rather than to simply replicate the<br />

picturesque landscape parks that had made the Olmsted firm successful in the East, instead to<br />

reference, highlight and capture the natural scenery unique to the Pacific Northwest, while<br />

constructing a network of parks on the scale of Boston’s Emerald Necklace. In an environment<br />

that still remained largely untamed, Seattle in 1903 was vastly different from the large industrial<br />

6<br />

Scott, D. Munson, W. “Perceived Constraints to Park Usage among Individuals with Low Incomes.” Journal of<br />

Park and Park and Recreation Administration 12, (1994): 52-69.<br />

7<br />

Zakarian, J.M. Hovell, M.F. Hofstetter, C.R. Sallis, J.F. Keating, K.J. “Correlates of Vigorous Exercise in a<br />

Predominantly Low SES and Minority High School Population” Preventive Medicine 23, (1994): 314-321.<br />

Gordon-Larsen, P. McMurray, R. G. Popkin, B.M. “Determinants of Adolescent Physical Activity and Inactivity<br />

Patterns.” Pediatrics 105, (2000): 1327-1328.<br />

4

cities east of the Mississippi, and thus the motivations behind the design of its parks differed in<br />

nature.<br />

Seattle was at that time a small city with large aspirations, which had been put on the map<br />

as a stop on the route to Alaska during the Klondike Gold Rush. It sought to grow its population<br />

and importance, first on the scale of West Coast cities like Portland and San Francisco, but<br />

ultimately to rival the Chicagos and Bostons of the east. Olmsted’s master plan for Seattle was<br />

not a counterpoint to the horrors of industrialization, but rather a way of city-building, an<br />

assertion of its equality to its east coast rivals, and a way of forming its own identity.<br />

Today, Seattle has grown into a city whose identity is inextricably linked to its<br />

geography, whose urban landscape is best captured in its public parks and university campus<br />

(also an Olmsted design). The city’s rich tradition of public park planning in many ways<br />

stemmed from John Charles Olmsted’s vision, and the relationship between its landscape and the<br />

public remains one that, while providing a cultivated and immersive experience for visitors,<br />

cannot be automatically understood to harbor a truly democratic nature. In order to properly<br />

assess the democratic nature of Seattle parks in 1903 and today, a history of the western origins<br />

of the public park and the social milieux in which they were produced must be conducted. The<br />

ultimate goal, then, is not to provide a solution for existing inequality in urban public space, but<br />

rather, to understand how the definition of the dual terms “public” and “park” have changed<br />

through time, and how their modern definition shapes conditions of access and equity today.<br />

This project begins by conducting a broad historical survey of park planning precedents<br />

from Rome through the year 1903. It will focus on concepts such as lex hortorum and rus in urbe<br />

as they respectively pertained to the public use of private gardens and parks, and the<br />

conceptualization of parks as bringing elements of nature and the pastoral aesthetic into the city.<br />

5

These ideas in turn proved consequential for the discourse and thought that went into the<br />

planning of parks in eighteenth and nineteenth century England. The design of English squares<br />

and parks like Covent Garden and Sir Joseph Paxton’s 1847 Birkenhead Park, influenced and<br />

informed the design of Frederick Law Olmsted’s Central and Prospect Parks in New York, in<br />

turn proving instrumental for the designs of Seattle parks in the early twentieth century. Beyond<br />

speaking to ideals of romanticism and wilderness, parks like John Charles Olmsted’s Green Lake<br />

Park and Volunteer Park serve as examples of the production and preservation of a naturalistic<br />

landscape for the recreation and pleasure of the public. How these ideas about public greenspace<br />

came to be is the subject of the present investigation.<br />

6

Section 1—History of the Public Park in Ancient Rome<br />

The concept of the urban park has been present since before common era, but the western<br />

roots of public park patronage first emerged in Rome, in the form of privately held estates known<br />

as horti. The Roman hortus is the first formal antecedent to the public park in the West. Horti<br />

were the private gardens of military leaders that were designed to showcase the illustriousness<br />

and wealth of their owners. They were peri-urban sites, meaning that they were located outside<br />

of the Roman walls, and thus took on an aesthetic consistent with their rural surroundings. These<br />

greenspaces were not characterized by the careful planning and sequencing of views as with the<br />

formal urban garden parks that were to follow, but rather took on varied forms, from paradisal<br />

hunting parks to small villa gardens. 8 Taylor et al. write, “Initially, owning one was the<br />

prerogative of men who had distinguished themselves in the public or martial sphere [...]<br />

naturally, then, horti functioned simultaneously as elite retreats and public signifiers of power<br />

and ideology.” 9<br />

The origins of porticus are somewhat different from those of those of the hortus. The<br />

porticus was an outgrowth of an architectural development—before taking on its present<br />

association with the urban garden, it simply signified a colonnaded porch at the entrance of a<br />

temple or other building, a concept adopted from the Greek which, to this day, remains the<br />

common western usage of the term portico. The term porticus, meaning colonnade, refers to a<br />

distinct garden typology, whereas the hortus could take on any number of aggregate forms, with<br />

8<br />

Taylor, Rabun, Katherine W. Rinne, and Spiro Kostof, eds., “Rus in Urbe: A Garden City,” in Rome: an Urban<br />

History from Antiquity to the Present, Cambridge, 2016, chapter 11, 108.<br />

9<br />

Ibid, 109.<br />

7

no expense spared in their opulent articulation. Specifically, the porticus developed out of the<br />

Hellenistic peristyle garden that was common to Greek villas. 10 While the peristyle garden often<br />

consisted of a colonnaded courtyard or ornamental garden, the porticus was characterized by a<br />

grove of plane trees, known as a nemus, surrounded by a colonnade, the effect of which provided<br />

a “new, unified spatial organization” that was distinctive from the hortus on the surrounding hills<br />

of Rome. 11 The impact of the porticus on garden design was tremendous: it represented a highly<br />

ordered design, in which views and procession were orchestrated by the architectural and natural<br />

elements.<br />

The porticus was a distinct development that instead integrated the garden within an<br />

urban site. In “Porticus Pompeiana: a new perspective on the first public park of ancient Rome,”<br />

Kathryn Gleason describes the way in which the porticus differs from the hortus. She notes that<br />

while both hortus and porticus were associated with gardens of military landowners, the porticus<br />

had a greater function than demonstrating wealth and providing enjoyment for its owner. Instead,<br />

it took on a political role, due in part to its location in, rather than adjacent to the city, and its<br />

frequent proximity to important civic and social spaces. 12 The classical porticus design emerged<br />

in 55 BC, commissioned for Rome by the general Pompey the Great. 13 Situated in the Campus<br />

Martius, the park and its surroundings became known as the Opera Pompeiana. The surrounding<br />

buildings, including many of the elements of a classical Roman forum, became part of the<br />

composite public space. This composition not only transfigured the relationship between the city<br />

10<br />

Ibid, 103.<br />

11<br />

Gleason, Kathryn L. “Porticus Pompeiana: A New Perspective on the First Public Park of Ancient Rome.” The<br />

Journal of Garden History 14, no. 1 (1994): 13.<br />

12<br />

Gleason, 13.<br />

13<br />

The term porticus refers to the specific organization of formal gardens: the colonnaded nemus. While this term is<br />

the technical way to refer to this particular park typology, it is sparingly found in common usage. For this reason,<br />

excepting where it is used as a proper noun, the term porticus will heretofore be referred to as parco, the broader<br />

term used to describe Italian parks.<br />

8

and the landscape, but elevated the status of the park as a political and socially implicated space,<br />

due to its contact with the surrounding civic structures. The positioning of the parco in an urban<br />

context in proximity to important civic and social buildings such as a senate house and a market<br />

was a move on the part of Pompey to assert political power, but also imbued the park with an<br />

important public function to provide space for gathering outdoors, much like an Italian piazza.<br />

Fig. 1: Plan of the Campus Martius,<br />

with the Porticus Pompeiana highlighted in red<br />

Fig. 2: Plan of the Porticus Pompeiana in<br />

Lanciani’s 1893 Forma Urbis Romae<br />

reconstruction of ancient Rome<br />

In The Park and the Town, George Chadwick succinctly traces the concept of the<br />

porticus as parco to another location in ancient Rome, that of the Porticus Livia, stating, “the<br />

open area for public use is no recent idea—the town square or place is probably almost as old as<br />

settlement itself, starting as a mere space between dwellings which became used as a place for<br />

gatherings—even in Roman times we find gardens such as the Porticus Livia which were laid out<br />

for public use.” 14 The Porticus Livia, dedicated in 7 BC, stands as a prototypical example of the<br />

porticus type. The garden featured a double colonnade, or more likely a colonnade with an arbor,<br />

where a “single prodigious grapevine covered the entire portico.” 15 Additionally, fountains were<br />

14<br />

Chadwick, G. F. (1966). The Park and the Town: Public Landscape in the 19th and 20th Centuries. F. A. Praeger.<br />

15<br />

Taylor, et al. 107.<br />

9

located in the corners and center of the park, demonstrating a “prevailing taste for symmetry,<br />

rectilinearity, and orthogonality in Roman gardens.” 16<br />

The Domus Aurea<br />

With the Domus Aurea, a shift in park design occurred. The “Golden House of Nero” is<br />

an important example of the imperial parco that demonstrates the principle of rus in urbe.<br />

Though the Domus Aurea served as the imperial palace for the Emperor Nero (AD 37-AD 68), it<br />

is best known for its extensive and opulent gardens, and series of artificial landscapes that<br />

showcased the political might and the unparalleled wealth of the emperor. While the Domus<br />

Aurea was in itself an incredibly elite space, it also served a more public function as a space for<br />

urban gathering, feasting, and ceremonial events. Katherine Welch writes in The Roman<br />

Amphitheatre: From Its Origins to the Colosseum that the Domus Aurea served as a “quasipublic<br />

park,” where “people could at times come and go freely, and the upper classes perforce<br />

had to rub shoulders with everyone else whether they wanted to or not.” 17 Welch draws a<br />

distinction between an urban park such as the Domus Aurea and other pleasure spaces such as<br />

the Colosseum, where the upper class were spatially segregated and afforded the best views in<br />

the amphitheater, denying the possibility for interaction between classes.<br />

The gardens of Nero’s vast palace complex, built adjacent to the Forum Romanum, did<br />

not possess the deliberate symmetry and carefully orchestrated perspective of the porticus.<br />

Rather, the opulent, overwrought assemblage of building and landscape styles is the antithesis of<br />

16<br />

Ibid.<br />

17<br />

Welch, K. E., & Cambridge, U. of. The Roman Amphitheatre: From Its Origins to the Colosseum. Cambridge<br />

University Press, 2007, 159.<br />

10

the Porticus Pompeiana. Nero had based the plan on a seaside villa, quite literally importing a<br />

foreign landscape into the heart of the city, and thereby undermining essential Roman ideas of<br />

Fig. 3:<br />

18 th century<br />

perspective of the<br />

Domus Aurea, with<br />

the colossal<br />

Stagnum Neronis<br />

visible at the<br />

center. Tiny figures<br />

can be seen milling<br />

about the villa,<br />

showing the public<br />

function of Nero’s<br />

villa.<br />

order, perspective, and symmetry. In addition to providing a space for public diversion and<br />

interaction, the Domus Aurea also embodied the concept of rus in urbe, a principle which, as<br />

will be discussed later, provided the conceptual organization for many of the parks in Victorian<br />

England. The term rus in urbe was originally coined by the epigrammist Martial (AD 40-AD<br />

104) who describes with envy in epigram LVII the luxury of the home of Sparsus, “whose<br />

mansion, though on a level plane, overlooks the lofty hills which surround it; who enjoy[s] the<br />

country in the city (rus in urbe).” 18 Martial contrasts the relentless clamor and disruption of<br />

Rome with the home of Sparsus, which, despite being located in the very same city, by nature of<br />

its sprawling views and seclusion through its gardens and spatial separation, creates the illusion<br />

of being in the quietude of the countryside, or rather, perhaps, of bringing the countryside into<br />

the city.<br />

18<br />

Martial, Epigrams, ed. & tr. D.R.Shackleton Bailey, Cambridge, 1993, vol. III, Book XII, 59, 139.<br />

11

Nero’s Domus Aurea epitomized this landscape typology through the construction of an<br />

artificial lake, the Stagnum Neronis, in addition to groves, vineyards and pastures. As the Domus<br />

Aurea is no longer extant, and its remains, though preserved underneath the heart of the modern<br />

city, are largely inaccessible, the most detailed accounts of the site can be found in the Roman<br />

biographer Suetonius’s Life of Nero (AD 121) and historian Tacitus’s Annals (AD 109).<br />

Suetonius describes the Domus Aurea as:<br />

A palace extending all the way from the Palatine to the Esquiline [...] large enough<br />

to contain a colossal statue of the emperor a hundred and twenty feet high; and it<br />

was so extensive that it had a triple colonnade a mile long. There was a pond too,<br />

like a sea, surrounded with buildings to represent cities, besides tracts of country,<br />

varied by tilled fields, vineyards, pastures and woods, with great numbers of wild<br />

and domestic animals. 19<br />

Suetonius’s description of the grounds of the Domus Aurea demonstrates precisely what the term<br />

rus in urbe denotes, and Tacitus corroborates with his description of Nero’s landscape:<br />

A palace, the marvels of which were to consist not so much in gems and gold,<br />

materials long familiar and vulgarized by luxury, as in fields and lakes and the air<br />

of solitude given by wooded ground alternating with clear tracts and open<br />

landscapes. 20<br />

Above all, these two depictions of the Domus Aurea demonstrate the existence of rus in urbe as<br />

a concept guiding landscape design dating back to Roman times and recurring as a landscape<br />

typology well into the Nineteenth Century in Europe, and ultimately in America.<br />

19<br />

Tranquillus, C. Suetonius. 31, In The Life of Nero. Translated by Bill Thayer., 137.<br />

Originally published as De Vita XII Caesarum.<br />

20<br />

Tacitus. "42." In Book XV, 281. Translated by J.C. Rolfe. Vol. 5 of The Annals of Tacitus. Cambridge, MA:<br />

Harvard University, 1937.<br />

12

Fig. 4: Lanciani’s Map of Rome overlaid with the plan of the Domus Aurea.<br />

The Coliseum is visible at lower left.<br />

The Domus Aurea cannot be read as a publically available parco due to its sprawling,<br />

multi-use nature and Imperial ownership. However, it can certainly be read in tandem; although<br />

it would be difficult to claim that the Domus Aurea was designed specifically to suit the needs of<br />

the public in mind, it demonstrates a consciousness of common usage. This is demonstrable<br />

through accounts of the spectacle that occurred on the palace’s grounds, including lavish feasts<br />

and the staging of entertainment along the Stagnum Negronis. Welch concedes that the claiming<br />

of the center of Rome for Nero’s Domus after the great fire of 64 AD drew intense criticism,<br />

particularly from the Roman elite, but she maintains that this criticism was for the most part<br />

because the land that he appropriated was occupied mostly by the elites themselves, rather than<br />

by the poor, as Martial claimed. 21 Rather than undertake a reading of the Domus Aurea as a<br />

21<br />

Martial, qtd. In Welch, 152.<br />

13

space purely of private indulgence, then, in Welch’s view, the Domus takes on a more nuanced<br />

role in the urban landscape of Nero’s Rome. Moreover, the construction of the Domus Aurea had<br />

the effect of making available exclusive territory for the enjoyment of the public. “To some<br />

extent,” writes Welch, “[Nero] seems to have been using coveted property in the heart of the city<br />

as a public park that extended to the Roman people, at least some of the time, pleasures hitherto<br />

restricted to extra-urban horti and villas of the elite.” 22 Such an intersection of class and public<br />

and private space would have been unlikely prior to Neronian Rome, but Nero’s actions, though<br />

soundly criticized and often considered megalomaniacal, fortunately made a strong case for<br />

making central Rome available to the public, as it later was with the construction of the<br />

Colosseum in its place. For the purposes of the present study, Nero established a landscape<br />

typology that would in turn influence spaces in England and finally, in Frederick Law Olmsted’s<br />

ideas of landscape use and design.<br />

Baroque Parks in 17th Century Rome<br />

During the Renaissance, the public nature of the parco became further cemented with the<br />

emergence of a vocabulary to discuss the domain of parks. David R. Coffin traces the earliest<br />

instance of lex hortorum to the late fifteenth century, summarizing its principle to be “that<br />

gardens are created not only for the personal enjoyment of their owners, but to afford pleasure to<br />

their friends and even to strangers and the public, diminishing the concept of private property.” 23<br />

The term lex hortorum thus can be understood to describe the informal, though often explicit<br />

public right to the use of private parks and villas. In private parks like the Villa Borghese and the<br />

22<br />

Welch, 157.<br />

23<br />

Coffin, David R. “The ‘Lex Hortorum’ and Access to Gardens of Latium During the Renaissance.” The Journal<br />

of Garden History 2, no. 3 (1982): 201-232.<br />

14

Domus Aurea, the landscapes served to display the wealth and prominence of their patron;<br />

however, unlike the Domus Aurea, the grounds were laid out with visitors in mind in the Villa<br />

Borghese. Before the emergence of lex hortorum, the right to patronize private gardens was<br />

informal at best. After, public patronage of private gardens became much more common, to the<br />

extent that there existed written acknowledgements of the practice, though it was still not<br />

codified by law. An appeal to exercise lex hortorum can be found on the inscription on the<br />

entrance to the Villa Borghese, which reads, among other text:<br />

Whoever you are, if you are free, do not fear here the letters of the law.<br />

Go where you wish, pluck what you wish, leave when you wish.<br />

These things are provided more for strangers than for the owner. 24<br />

As such, it was common practice for the public to visit the park within the villa four days a week.<br />

Further demonstrating the de facto public nature of the Villa was the means of entry: the Villa<br />

could be accessed by the public via a separate gate, while guests and family used a private<br />

entrance.<br />

Fig. 5. Plan of the<br />

Villa Borghese before<br />

1695. The public<br />

entrance is<br />

highlighted at lower<br />

right, with the private<br />

entrance shown<br />

above.<br />

Private entrance<br />

Public entrance<br />

24<br />

Ibid, 202.<br />

15

The Villa Borghese<br />

The Villa Borghese, though a later product of the Renaissance, continued to operate<br />

along the principles of rus in urbe and lex hortorum; despite its being designed and built for the<br />

Borghese family, it took on an important public function after it was constructed. The original<br />

plan, laid out starting in 1606, was more garden than park; immediately surrounding the villa<br />

were formal gardens planted in a highly ordered, rectilinear manner. Adjacent to the Villa was a<br />

rustic hunting ground. 25<br />

Fig. 6. Oil painting by Heinz the<br />

Younger of the formal gardens of<br />

the Villa Borghese before the<br />

landscape was transformed.<br />

In what Coffin describes as the second phase of the Villa’s design evolution, beginning<br />

around 1620, the park was laid out to provide even greater contrast between formal and rural<br />

landscapes. This was accomplished by converting the gardens into formal tree gardens and<br />

planting sections of the hunting park to resemble a rustic wilderness, while retaining the pastoral<br />

aspect in others, including a meadow that was mowed just twice a year. 26 This transformation<br />

effectively brought intentionally unkempt nature into contact with the city via artificial means.<br />

25<br />

Ibid, 1.<br />

26<br />

Ibid, 2.<br />

16

Though the terms “park” and “garden” are used somewhat interchangeably by historians<br />

(Gleason, 1994; Welch, 2007; Taylor et al. 2016) to refer to Roman imperial horti and porticus,<br />

Mirka Benĕs makes the claim in “The Social Significance of Transforming the Landscape at the<br />

Villa Borghese, 1606-30: Territory, Trees, and Agriculture in the Design of the First Roman<br />

Baroque Park” that the Villa Borghese stands as the first parco in Rome. 27<br />

The Villa was commissioned in 1606 by Cardinal Scipione Borghese, whose authority<br />

was only outranked by his uncle, Pope Paul V, and designed by the architect Flamonio Ponzo.<br />

Located on the northern border of Rome, the villa covered a 160 acre expanse, a feat of private<br />

ownership that would not have been possible if not for the gradual acquisition of land on the part<br />

of Scipione, and the villa’s position on the periphery of the city, which allowed for the ambitious<br />

plan to be laid out without the conflict of land usership as arose with the Domus Aurea. The<br />

result was a park that “consisted of two major parts: the giardini, which surrounded a palace and<br />

Fig. 7. Perspective of the<br />

Villa Borghese in phase<br />

two after the<br />

transformation of the<br />

formal gardens into a<br />

tree garden, with views<br />

of rural fields beyond.<br />

27<br />

Benes, Mirka. "The Social Significance of Transforming the Landscape at the Villa Borghese, 1606-30: Territory,<br />

Trees, and Agriculture in the Design of the First Roman Baroque Park." In Gardens in the Time of the Great Muslim<br />

Empires: Theory and Design, edited by Attilio Petruccioli, 1-31. Leiden; New York: E.J. Brill, 1997.<br />

17

which were formally ordered gardens constructed on leveled ground; and the barco, adjacent to<br />

these gardens, which was a hunting park laid out on mostly unaltered terrain.” 28 The giardini,<br />

with its fountains and manicured greeneries, stood in direct contrast to the barco, with lakes,<br />

groves, grazing livestock and wild game, which “recalled the landscape of the Roman<br />

countryside, where large farms (casali) were endowed with grassy meadowlands devoted mostly<br />

to grazing and partly to hunting.” 29<br />

Benĕs notes that Borghese looked to the royal gardens in Paris and Madrid for<br />

inspiration, and the construction of a spectacular park within the city of Rome was thus a gesture<br />

intended to align the Borghese family with the likes of European royalty. By building a private<br />

park, the Borghese family in effect placed a premium on the land, demonstrating their wealth to<br />

be so extravagant as to allow land within the city to be undeveloped and available for pure<br />

leisure and visual enjoyment as opposed to development and habitation. Before this time,<br />

suburban villas or hunting parks well outside the city would have been the only kind that<br />

matched the type of park that Cardinal Scipione Borghese sought to create within the city. The<br />

construction of the Villa required the complete fabrication of a forested area with careful<br />

landscaping, as Rome’s interior had for a long time been deforested. 30 Benĕs writes, “the<br />

artificial re-creation of rus in urbe in the Villa Borghese represented a typological nov-elty: an<br />

artificially re-created rural landscape, which imi-tated aspects of genuine rural landscapes<br />

situated in an-other zone of territory.” 31 Scipione’s villa was used to host extravagant banquets<br />

28<br />

Ibid, 1.<br />

29<br />

Ehrlich, T. L. Landscape and Identity in Early Modern Rome: Villa Culture at Frascati in the Borghese Era.<br />

Cambridge University Press, 2002, 41.<br />

30<br />

Benĕs, 2.<br />

31<br />

Benĕs, 3.<br />

18

and hunting trips for nobility and foreign dignitaries alike, but also was made available for public<br />

admiration and visitation.<br />

Hunt’s Three Natures and the Villa Borghese<br />

The presence of formal gardens, hunting park, and grazing meadow in the design of the<br />

Villa Borghese coincides with a movement that English landscape historian John Dickson Hunt<br />

describes as “three natures.” In this concept, first, second, and third natures refer to different<br />

states of human interaction and/or interference with the landscape. First nature refers to the<br />

wilderness, or nature as untouched by humans, whereas second nature is agrarian, and third<br />

nature is the highly cultivated landscape, or the art of landscape design. He traces the idea of<br />

third nature to the Italian Humanists Bonfadio and Taegio, who both write of a “third” nature in<br />

works dating from 1541 and 1559 respectively. 32 Bonfadio writes in a letter to a colleague,<br />

For in the gardens...the industry of the local people has been such that nature<br />

incorporated with art has made an artificer and naturally equal with art, and from them<br />

both together is made a third nature, which I would not know how to name. 33<br />

Bonfadio seeks to describe something beyond the cultivation of land and uncultivated nature<br />

alone, but rather what exists when the two come together. In his reading, the garden is thus not a<br />

separate entity altogether, but a composite of nature and artifice.<br />

Second nature is a term that was coined in Roman times by Cicero. He describes the<br />

cultivated land as a way “by means of our hands we try to create as it were a second nature<br />

within the natural world.” 34 Hunt extends this definition to include not only the agrarian<br />

landscape, but also to include infrastructure. The manipulation of land on the part of humankind<br />

32<br />

Hunt, J. D. Greater Perfections: The Practice of Garden Theory. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000, 32.<br />

33<br />

Bonfadio qtd. In Hunt, 33.<br />

34<br />

Cicero, qtd. In Hunt, 33.<br />

19

to support the needs of humankind, urban or rural, produces nature of a secondary form. While<br />

Cicero does not explicitly name the first form of nature, it is implied within his observation; it is,<br />

as Hunt describes, a “primal nature” that exists before and beyond human interference.<br />

The concept of three natures is an idea that was circulated during the Renaissance, but it<br />

should not be mistaken as a guiding principle for landscape design. Hunt writes, “It must be<br />

emphasized that the arithmetic of “three natures” is symbolic, not literal and certainly not<br />

prescriptive, nor does it necessarily privilege the third over the other two natures. It is meant to<br />

indicate [...] that a territory can be viewed in the light of how it has or has not been treated in<br />

space and time.” 35 What it lent to architects was a way of conceptualizing landscape design as an<br />

artistic pursuit, and furthermore, one that could incorporate all three natures within confined<br />

spatial boundaries. While it is possible that parks like the Villa Borghese existed beforehand, it<br />

was not until the articulation of this theory that it became possible to describe and apply its<br />

concepts. In Renaissance Italy, the parks that made use of the first, second, and third degree<br />

marked a shift in man’s relationship with nature. In the production of third nature parks and<br />

gardens, perspectives and geometry reigned, but it was also possible, as with the Villa Borghese,<br />

to produce, by means of artifice, a first nature—one that recalled the wilderness in an aesthetic<br />

sense, but which was entirely fabricated. This also extended to second nature; both ways of<br />

quoting nature and the rural landscape were a means of producing and recalling rus in urbe.<br />

Through its construction in urban Rome, the Villa Borghese can thus be read as a<br />

translation of the concepts of first, second, and third nature. The hunting park, with forested<br />

areas and shrubbery that created space for birds and animals to take refuge and provided game<br />

for hunters, was a fabricated form of first nature, whereas the central meadow provided second<br />

35<br />

Hunt, 35.<br />

20

nature, and axial walkways and formal gardens were of the third nature. The precedent for the<br />

incorporation of second nature in the Villa Borghese was drawn directly from the design of the<br />

Domus Aurea, with its pastures and fields that had the effect of producing rus in urbe. The Villa<br />

Borghese reignited the concept of rus in urbe by drawing on the landscape principles which<br />

Suetonius and Tacitus used to describe the Domus Aurea, producing hunting grounds, ploughed<br />

fields and a formalized garden all within an urban context. The rural aesthetic upon which the<br />

design of the second nature section of the villa was based drew a connection with the extraurban<br />

roots of the Italian aristocracy to which the Borghese belonged. The tradition of apportioning<br />

land to military leaders and elected officials had produced the peri-urban horti that surrounded<br />

the city of Rome, and conferred social and monetary status to landowners. For this reason, the<br />

choice to draw upon a pastoral aesthetic had the effect of gesturing back to a family’s propertied<br />

lineage, in addition to providing a visual and sensory retreat for the Borghese family. 36<br />

This implicit agreement for public use of the villa proved to be contentious when, in<br />

1885, the Prince Marcantonio Borghese attempted to close the grounds of the villa to the public,<br />

an act which resulted in the legal rebuke of the city, and the state’s eventual acquisition of the<br />

park in 1901. This conflict demonstrates the difficulty inherent with such an informal agreement:<br />

in the instance in which common practice diverges from actual legal right, the course of action<br />

becomes much more fraught. Such debates continue to exist today, proving a further difficulty of<br />

determining where public right falls on a basis both legal and precedential.<br />

In Landscape and Identity in Early Modern Rome, Erlich notes, “In the environs of the<br />

palace Scipione developed a park that foreshadowed English landscape gardens of the following<br />

century.” 37 The design of the Villa Borghese, in reproducing elements of the pastoral in the<br />

36<br />

Benĕs, 5.<br />

37<br />

Erlich, 43.<br />

21

urban setting, had the same effect two centuries later with the pastoral English garden, which<br />

transformed the conception of public space in Victorian London. The tradition of lex hortorum<br />

had a lasting impact in the conceptualization of parks across Europe, and the villa park typology<br />

of the Villa Borghese established a paradigm that was translated into parks in England and<br />

eventually Paris. Likewise, the concept of making privately owned parks available to the public<br />

served as a key precedent for the later proliferation of public parks in the late nineteenth and<br />

early twentieth centuries in Europe and the United States, thus marking a shift from a societal<br />

understanding of parks as elite, private spaces to their containing a prerogative for public use.<br />

22

Section 2: English Park Design in 16th-19th Century London<br />

Italian ideas of rus in urbe and making parks and gardens available to the public left a<br />

lasting impact on parks across Europe, and most notably, in London. The public parks that define<br />

London’s identity today evolved along two separate trajectories: those of the town square and the<br />

royal garden. The private-use-only squares constitute many of the city’s smaller greenspaces, and<br />

provide a foundation around which much of the city’s architecture was built, whereas the parks<br />

and gardens owned by the Crown were much larger and detached from urban life. However, as a<br />

result of mounting pressure to make greenspaces available to the working classes of industrial<br />

London, both of these types became incorporated into the public domain in the Victorian era.<br />

Public Patronage of Peri-urban Fields<br />

Although the term lex hortorum did not arise until the late fifteenth century in Italy, as<br />

previously indicated, the Romans were accustomed to visiting the Domus Aurea and other<br />

private parks even before such common rights were codified. England was much the same;<br />

though public squares such as Covent Garden and royal parks like Hyde Park were not made<br />

public until the 1630s, 38 it was common for Londoners to make public use of the fields to the<br />

north of the city, which were known as the Moorfields. 39 During that time, public access to green<br />

spaces was uncommon, and the Moorfields became a popular place for citizens to ‘walke in, to<br />

take the ayre and for Merchants’ maides to dry clothes in, which want necessary gardens at their<br />

38<br />

Covent Garden was a public plaza from the outset, but it was not constructed until 1630; Hyde Park was a royal<br />

hunting garden that was made available to the Public in 1635 by King Charles 1.<br />

39<br />

Alternatively Moorefields, Morefields, Morefeildes, or Moore-fields.<br />

23

dwellings.’ 40 The Moorfields were acquired by the city of London in the twelfth century, and the<br />

earliest record of public use dates to 1173. 41 In 1606, the city went so far as to plant tree-lined<br />

walks, drained the moor, and landscaped the fields “in the fashion of a crosse, equelly divided<br />

fooure wayes, and likewise squared about with pleasant wals: the trees thereof makes a gallant<br />

shew, and yeelds unto [the] eye much delight.” 42<br />

The resulting site contained all of the ingredients of a park as it might be understood<br />

today; it featured walkways, open space, and benches, trees and other plantings. 43 Its location on<br />

the periphery of the city brings to mind the peri-urban horti of the Roman military elite, and its<br />

transition from rural to landscaped design recalls the transformation of the Villa Borghese.<br />

However, further reading of the site is ill-advised, as it was not understood to be either park or<br />

garden by its users of the time. Instead, it should be understood to be an early example of public<br />

use of green space, and in its seventeenth century improvements and usage, an English example<br />

demonstrative of the principles of lex hortorum.<br />

Town Gardens and Square Gardens<br />

Preceding the development of the English Landscape Movement and the public pleasure<br />

garden and walk of Victorian England was the development of a vernacular of members-only<br />

town squares within the city of London. Before these private communal spaces arose, however,<br />

there existed a vibrant tradition of residential gardening. Ranging from modest vegetable gardens<br />

to ornate and fanciful pleasure gardens in miniature, these gardens arose to occupy the negative<br />

40<br />

Johnson, R., & Collier, J. P. The pleasant walkes of Moore-fields: being the guift of two sisters, now beautified, to<br />

the continuing fame of this worthy city, 1607, 6.<br />

41 Longstaffe-Gowan, Todd. The London Square: Gardens in the Midst of Town. The Paul Mellon Centre New<br />

Studies in British Art. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012, 19.<br />

42<br />

Ibid, 7.<br />

43 Longstaffe-Gowan, 19.<br />

24

space that resulted from the proliferation of terraced housing in eighteenth and early nineteenth<br />

century London. The urban landscape of London in the early eighteenth century was a<br />

piecemeal composite of terrace housing, a technique first employed in London by Nicholas<br />

Barbon (1640-1698). Early examples of this technique of uniting housing in a continuous facade<br />

exist in Grosvenor Square, beginning in 1727, and later Carlton House Terrace on St. James’<br />

Park. Todd Longstaffe-Gowan writes in The London Town Garden, “The formula transformed<br />

the structure of old (infill) and new residential quarters of the city and made the terrace house —<br />

usually run up in short, discontinuous strings—the dominant housing form for both urban and, in<br />

many cases, suburban housing well into the nineteenth century.” 44<br />

An outgrowth of the development in housing was the formation of small private gardens<br />

for growing vegetables or for the simple pleasure that gardening afforded the middle-class<br />

renters who took up residence in London. A town garden was a means of displaying one’s status,<br />

an expression both artistic and aspirational. These gardens were limited in scale to the space that<br />

was not occupied by terraced housing, and by the means of their owners—that is to say, they<br />

were not the gardens of the aristocrats, per se, but rather those of the middle-class, albeit a wellto<br />

do group of Londoners. 45 Because residential gardening constituted a private and hobbyist’s<br />

pursuit, the impact of these gardens did not extend far beyond their walls. However, this tradition<br />

of engagement with the land tied urban London to an agrarian and rural tradition in a way that<br />

should not be overlooked. The residential garden on the small scale was not a mere claiming of<br />

infill space, but a deliberate insertion of greenery within the city, and a claiming of the tradition<br />

of gardening and landscape design that had long flourished in the English countryside. Though<br />

44<br />

Longstaffe-Gowan, Todd. The London Town Garden, 1700-1840. The Paul Mellon Centre New Studies in<br />

British Art. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001.<br />

45<br />

Ibid.<br />

25

the practice of residential gardening was restricted to the middle- and upper-classes, the ability to<br />

train and cultivate the land was made available to a swath of the city’s population in a way that<br />

larger pleasure gardens and royal gardens were not until the mid-nineteenth century.<br />

The garden square, on the other hand, played a much larger role in defining London’s<br />

built landscape, and as a result, was instrumental in the city’s development of parks and public<br />

space in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. As with Roman villas like the Villa Borghese,<br />

London’s squares were first laid down during the mid-seventeenth century by aristocratic<br />

landowners who sought to amass wealth through land holdings. Sigfried Giedion cites Covent<br />

Garden as the first square in London, designed to be a garden for the Earl of Bedford in 1630. 46<br />

Taking cues from Paris’s Place des Vosges, both gardens in turn drew from the model of the<br />

Italian piazza. Covent Garden Piazza 47 , like the Place des Vosges, featured a paved and open<br />

central space surrounded by arcaded houses. In “The Greening of the Squares of London:<br />

Transformation of Urban Landscapes and Ideals,” Henry W. Lawrence describes an<br />

irreconcilable tension that arose as a result of the public nature of the square and its intended role<br />

a residential square, asserting that “by failing to provide a separate market square, [the Earl of<br />

Bedford] had condemned the residential square itself to a public commercial role that ultimately<br />

would be its undoing as an elite residential quarter.” 48 It was not until the Georgian period of the<br />

early eighteenth century that London’s squares would become standardized, planted with grass<br />

instead of paved, and surrounded by fencing, a practice that claimed them for the middle class<br />

46<br />

Giedion, S. Space, Time, and Architecture: The Growth of a New Tradition. Cambridge: Harvard University<br />

Press, 1962, 722.<br />

47<br />

Demonstrating its direct descent from the Italian piazza, Covent Garden was initially called Covent Garden<br />

Piazza. From this point forward it will be referred to as Covent Garden, which is the name that it goes by today.<br />

48<br />

Lawrence, Henry W. "The Greening of the Squares of London: Transformation of Urban Landscapes and<br />

Ideals." Annals of the Association of American Geographers 83, no. 1 (1993): 94.<br />

26

and sealed their legacy as such. 49 Longstaffe-Gowan describes this legacy in The London<br />

Square: Gardens in the Midst of Town: “The residential or garden square is a uniquely English<br />

device. It is, in fact, pre-eminent among England’s contributions to the development of European<br />

town planning and urban form, as it introduced the classical notion of rus in urbe.” 50 Though the<br />

Italians originated the notion that elements of the natural landscape and pastoral aesthetic belong<br />

in the city, the English take credit for adapting this concept for an unmistakably English setting,<br />

in a way that would eventually have significant implications for American park design.<br />

Drawing from ideas of rus in urbe in Italian parci and public space in Italian piazzas,<br />

London’s planners sequestered undeveloped parcels of land and apportioned them for the<br />

eventual construction of parks. It was around these parcels that residential London’s core of<br />

terraced housing arose. 51 In Space, Time and Architecture, Sigfried Giedion references an 1887<br />

definition of “the square” as “a piece of land in which is an enclosed garden, surrounded by a<br />

public roadway, giving access to the houses on each side of it.” 52 This definition serves as a<br />

practical template for many of London’s squares. Notable in this definition is the word<br />

“enclosed”—one of the most significant features of these gardens was that they were indeed<br />

enclosed by fences and intended to be used only by the inhabitants of the houses lining the<br />

square. While the London square gardens developed as a dominant type in during the eighteenth<br />

century, they were sites of exclusion: many of the squares were gated and required paid<br />

membership; only those who possessed keys were allowed to roam freely within their bounds.<br />

Further cementing the status of squares as private gardens, residents of London’s squares were<br />

49<br />

Lawrence notes that it was not until later that the practice of locking gated squares arose, but the effect of erecting<br />

fences was enough to send a potent message to the public to keep out (97).<br />

50<br />

Longstaffe-Gowan, 2012, 2.<br />

51<br />

Ibid, 4.<br />

52<br />

Giedion, 718.<br />

27

able to petition for legal permission to enclose them. Parliamentary acts preceded the formation<br />

of many private squares, the likes of which included St. James’s Square, Lincoln’s Inn Fields,<br />

Berkeley Square, Grosvenor Square, and Red Lion Square, for which acts were passed in in<br />

1725, 1734, 1766, 1774, and 1737 respectively. 53 Once a legal precedent for the privatization of<br />

squares was established, the square typology radiated throughout the city. As Giedion points out,<br />

the result of developing the city in the repeating pattern of garden square flanked by stately<br />

domiciles brought new form to a city without guiding axes or “comprehensive unity.” 54 The<br />

overall effect of reshaping residential London around garden squares was to create a city<br />

“determined by the building activities of the upper middle class.” 55 While this practice elicits<br />

little shock today, at a time in which many American cities are being overwritten by the likes of<br />

real estate developers, gentrifiers, and tech companies, this movement must be read in its own<br />

historical context. London of the early nineteenth century was a city that had been completely<br />

transformed by industrialization. It was one of profound disparity, whose lower classes bore the<br />

marks of the complete reshaping of urban life. The architecture of a city of closed gardens and<br />

upper middle class residences was not reflective of the advantages of society at large, but the<br />

privileges of a powerful and elite minority. Even as some of these spaces later became available<br />

to the public, London’s garden squares were by design intended to keep the lower classes out.<br />

James Ralph comments on Leicester Square, one of the earliest squares in London, in A Critical<br />

Review of the Publick Buildings, Statues and Ornaments In, and about London and Westminster,<br />

describing the relationship between the the gated square, laid out by the Earl of Leicester in<br />

1635, and its unwelcome neighbors. “Leicester-Square has nothing remarkable in it,” muses<br />

53<br />

Longstaffe-Gowan, 2012, 55.<br />

54<br />

Giedion, 717.<br />

55<br />

Ibid, 716.<br />

28

Ralph, “but [for] the inclosure in the middle, which alone affords the inhabitants round about it,<br />

something like the prospect of a garden, and preserves it from the rudeness of the populace<br />

too.” 56<br />

Fig. 8. Leicester Square, circa 1750.<br />

Implicit in the idea of the square is the exclusion it was meant to foster. As Ralph demonstrates,<br />

the pervasive sentiment among those perpetuating this exclusion was that public space fostered<br />

criminal activity and objectionable behavior, crowding and filth. The proper maintenance of<br />

gardens, and finally, their enclosure, could keep these behaviors out, and in doing so, would send<br />

a strong message: gardens were a privilege of the wealthy, and allowing the lower classes to<br />

patronize them would be an invitation to disease and crime, and would place such spaces at risk<br />

of falling into disrepair. Even before London squares were made private, Lawrence argues that<br />

they were designed to be spaces of exclusion, stating: “A maintained garden, then, became an<br />

asset in efforts to control the public use of these open spaces. In this we can see one of the seeds<br />

for the later use of gardens, viz., as ways of expressing control over socially contested space.” 57<br />

56<br />

Ralph, J. A Critical Review of the Publick Buildings, Statues and Ornaments In, and about London and<br />

Westminster: To which is Prefix’d, the Dimensions of St. Peter’s Church at Rome, and St. Paul’s Cathedral at<br />

London. C. Ackers, 1734, 30.<br />

57<br />

Lawrence, 97.<br />

29

This concept continues to hold weight today, and will be further discussed in relation to Seattle’s<br />

public park system. Moreover, Lawrence’s observation raises an important question of who<br />

exercises control over public space, and how landscape can be used in the service of those in<br />

power.<br />

In addition to keeping others out, the effect of enclosing garden squares was to create a<br />

standard of conduct within and upkeep for these spaces. 58 By paying membership, residents were<br />

granted access to flora, landscaped walkways, and a community sharing equal social privilege.<br />

Unlike residential town gardens, users were not responsible for the upkeep of these spaces, and<br />

as a result, the emphasis shifted away from landscape cultivation as an artistic and leisurely<br />

pursuit, and toward landscape as a facilitator of social interaction. For the children who formed<br />

friendships and were allowed to play safely without the need for adult supervision, the square,<br />

forming a communal space for play outside of the house, was the center of the social<br />

community. 59 For residents of London’s squares, access to private gardens afforded them<br />

security and increased property values in the neighborhood. Additionally, in belonging to a<br />

singular class of people whose codes of conduct and social mores were already well understood,<br />

emphasis was placed less on the policing of these spaces or their use for public display, and more<br />

on their role as spaces for private leisure. “The squares became extensions of the private lives of<br />

their occupants,” writes Lawrence. “In short, they had become domesticated, transformed from<br />

public piazzas into private parks.” 60<br />

The enclosure of squares inflicted further damage to the right of commons that had<br />

existed for centuries in open spaces such as the Moorfields. In eighteenth century London,<br />

58<br />

Longstaffe-Gowan, 2012, 4.<br />

59<br />

Ibid, 2.<br />

60<br />

Lawrence, 108.<br />

30

greenspace was rarefied ground, an amenity that was extremely limited for the lower classes. At<br />

the end of the eighteenth century, social and religious unrest led a Methodist revival and anti-<br />

Catholic rioting in 1780. The Moorfields provided a staging ground for these activities, and the<br />

political charge that this public space had taken on was condemned by the city. As a result, the<br />

Moorfields were converted to the private Finsbury Square in the 1790s, ending its tenure as a<br />

public space. 61 The public health movement would mark a transformation in the view of open<br />

space from a luxury of the rich to a human right, and Finsbury Square would once again<br />

transition to public use, but until this moment in time, the fate of many parks and greenspaces<br />

were subject to the whims of the ruling class.<br />

61<br />

Ibid, 99.<br />

31

Rus in Urbe in the London Square<br />

In the early days of the development of London’s squares, the tenants occupying the<br />

surrounding residences were frequently wealthy country estate holders who spent the winter<br />

months in the city. It is unsurprising, then, that early garden squares developed out of a rural<br />

aesthetic. Early squares such as Lincoln’s Inn Fields and Hanover, Grosvenor, and Soho Squares<br />

were located on the periphery of the city, and easily drew visual linkages to the countryside just<br />

beyond.<br />

Fig. 9. View of Soho Square in 1731<br />

looking north. The uniform terrace<br />

housing enclosing the square, while a<br />

carriage road skirts it. There is<br />

sparse planting, with few trees,<br />

which is consistent with early<br />

English squares. Visible behind the<br />

housing is open countryside. The<br />

visual axis of the road at center<br />

draws a visual link between the<br />

landscaped square and the<br />

countryside beyond.<br />

The proximity of rural land allowed squares to mediate the relationship between city and<br />

country, and in cases like Queen’s Square, built in 1708, and Hanover Square, built in 1714,<br />

newly minted squares often were designed to preserve views of the hills surrounding the city,<br />

thereby “strengthen[ing] the suggestion that the garden was an extension of the neighboring<br />

countryside.” 62 Additionally, as Parliamentary acts gave jurisdiction of squares to their residents,<br />

their design was also in their control, and as a result, the landscaping of squares naturally took on<br />

62<br />

Longstaffe-Gowan, 2012, 44.<br />

32

the rural aesthetic that appealed to the country-dwellers who took up residence there during the<br />

winter.<br />

In 1722, Thomas Fairchild, a London Gardener, published The City Gardener, giving his<br />

recommendations for designing London squares in the “country manner.” Besides describing the<br />

best trees and plants with which to adorn them, he advocates for the creation of gardens in town<br />

that would provide city-dwellers a taste of “the pleasures of their Country Gardens.” Fairchild<br />

contends that instead of “laying out Squares in Grass Platts and Gravel Walks [...] some sort of<br />

Wilderness Work will do much better, and divert the Gentry better than looking out of their<br />

Windows upon an open Figure.” 63 This conclusion demonstrates an important shift in thinking in<br />

the ornamentation of squares: instead of leaving them as paved, grassy, or with unobstructed<br />

views, the planting of London planes or other shade-giving trees evoked the groves of hunting<br />

parks and rural landscapes. Today’s squares generally reflect this legacy to the extent that<br />

Giedion maintains that “the main constituent of all the London squares is a central garden of<br />

grass and plane trees.” 64 Lawrence notes the evolution from Georgian gardens that were “based<br />

on the composition of framed views” to gardens at the end of the century, whose “goal was to<br />

evoke an image of nature itself, using broader views over the countryside framed by trees and<br />

woodland.” 65 This change can be read as a transition from the constraints of formal gardens to<br />

one that was increasingly influenced by rus in urbe and a pastoral aesthetic, and finally which<br />

evoked a conceptual link to wilderness or first nature.<br />

63<br />

Fairchild, T. The City Gardener: Containing the Most Experienced Method of Cultivating and Ordering Such<br />

Ever-greens, Fruit-trees, Flowering Shrubs, Flowers, Exotick Plants, &c. as Will be Ornamental, and Thrive Best in<br />

the London Gardens. T. Woodward, 1722, N. pag.<br />

64<br />

Giedion, 719.<br />

65<br />

Lawrence, 104.<br />

33

The Rise of Public Parks in Victorian London<br />

The history of public English gardens can be traced to an origin similar to those in Italy.<br />

The tradition of landscape architecture and park planning was largely a royal pursuit, with much<br />

of the large-scale parks and gardens belonging to or financed by the royal family. Still, following<br />

the Roman precedent, many of these parks designed and belonging to the Crown were made<br />

available to the public, a tradition dating to 1635, when Hyde Park was opened to the public by<br />

King Charles I. Nonetheless, this making available of royal spaces does not characterize the<br />

general nature of English parks. While many were built by the Crown, those predating the<br />

Victorian Era were not designed with public use in mind. Thus, while the history of public parks<br />

in England does not begin in the Victorian Era, this period can nonetheless be understood as<br />

foundational in the establishment and design of many of the public parks that exist in London<br />

today.<br />

George Chadwick traces the concept of public park to the Victorian era, noting, “The<br />

creation of useful landscapes within the town for the use and enjoyment of the public at large is<br />

essentially a Victorian idea, due in the first place to the phenomenal growth of the “insensate<br />

industrial town” which created the basic need for such areas.” 66 Although in earlier times private<br />

parks and gardens were understood to be part of the public domain via the concept of lex<br />

hortorum, Chadwick notes that “it was not until the nineteenth century that we find the public<br />

park as we know it, an area of land laid out primarily for public use amidst essentially urban<br />

surroundings.” 67 This functional definition of the public park as an urban greenspace devoted to<br />

the use of the public efficiently articulates our modern understanding of the term. As will be<br />

discussed later, the ownership of public parks—whether publicly or privately owned—in<br />

66<br />

Chadwick, 19.<br />

67<br />

Ibid.<br />

34

addition to their funding—whether governmentally funded or supported by a private<br />

organization or conservancy—further complicates this definition, but nonetheless does not affect<br />

our understanding of these parks as fundamentally for public use.<br />

The Royal Parks of London<br />

Despite the fact that most Royal parks were established exclusively with private use in<br />

mind, St. James’s Park stands out as an example of a Victorian park that was intended to be for<br />

public use. Chadwick makes the claim that for this reason, it stands as the first public park in<br />

England, despite the fact that it was not part of the movement that produced many of the public<br />

parks of the era. 68 It was consistent, however, in the image of the English landscape movement<br />

in which it was produced, and an example of the Reptonian landscape which proved influential<br />

in the imagination of park designers across England. This was a style based on the aesthetic<br />

influences of Humphry Repton, an eighteenth century English landscape gardener (1752-1818)<br />

who envisioned parks as an artistic pursuit that drew influences from the scenes of “idyllic, even<br />

mythic nature” 69 that constituted the European landscape painting tradition. Repton’s landscapes<br />

harkened to an ideal landscape, “the whole contrived so as to produce an appearance of nature in<br />

the midst of art,” 70 but “modified the ideal landscape thus conjured up to meet essentially<br />

practical considerations.” 71 While Repton executed few park designs in his lifetime, his ideas<br />

proved to be extremely influential, and his vision was eventually realized by the hands of<br />

landscape architect John Nash in Regent’s Park and St. James’s Park.<br />

68<br />

Chadwick, 34.<br />

69<br />

Lawrence, 100.<br />

70<br />

Chadwick, 29.<br />

71<br />

Ibid, 23.<br />

35

The Plan for Regent’s Park was produced in 1811, the resulting park featured a “large<br />

open park surrounded by a circular drive with buildings facing the drive and looking over the<br />

park.” 72 Nash’s plan for the park—which had existed as a hunting park known as Marylebone in<br />

the 17th century—transformed it from a tract of farmland into something which preserved the<br />

rural qualities of the English landscape. Aiding in the production of an agrarian environment was<br />

an artificial canal that opened to a man-made lake, upon which boats would ferry passengers<br />

back and forth for pleasure. A central circus built with villas was a formal element, but the lake<br />

was bifurcated to wrap around the crescent, and could be viewed through the thickets of trees,<br />

giving the scene a pastoral quality. Chadwick attributes the idea for the design that juxtaposed<br />

formal elements (the villa) with natural and organic ones (trees and fields) as one that was<br />

inspired by Repton, and compares Nash’s boating lake to Repton’s “use of cattle to give interest<br />

and scale in a park.” 73 Though the resulting park was complete in 1826, it was not made public<br />

until 1838. Nash’s park designs had garnered criticism for creating a “garden city for an<br />

aristocracy,” 74 and the pressure to open them to the populace eventually succeeded, though the<br />