Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

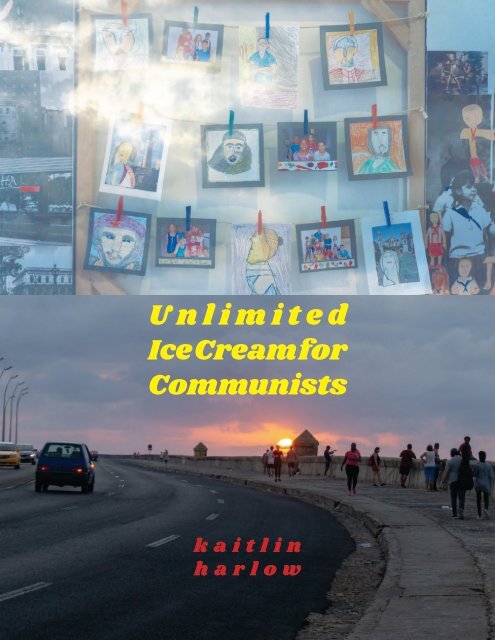

<strong>Unlimited</strong><br />

Ice Cream <strong>for</strong><br />

Communists<br />

kaitlin<br />

harlow

<strong>Unlimited</strong> <strong>ice</strong> <strong>cream</strong> <strong>for</strong> <strong>communists</strong><br />

W<br />

hile I was in Cuba, I never stopped sweating. The aggressive Caribbean<br />

sunshine turned my skin into an open, breathing organism. Through<br />

my sweating pores I absorbed salty gales along the Malecón, where the<br />

hot pink setting sun turned hundreds of meandering pedestrians into black silhouettes against the<br />

choppy Pacific Ocean. I soaked up scalding black exhaust spurting out of electric-green<br />

Volkswagens in downtown Old Havana. And degree by degree, as the sun burned ceaselessly down<br />

through my seven-day trip, I gradually absorbed curious insights into the lives of my new Cuban<br />

friends.<br />

I was in Havana <strong>for</strong> seven days on a trip with my seven closest friends. It was our last spring<br />

break in college, and as seniors we had no reason to shy away from the considerable cost,<br />

coordination, and logistics of pulling off an international escapade together. There was only one<br />

destination in our collective dreams: Cuba. Our friend Gaby was moving to Cuba that same week to<br />

be with Laura, her long-distance Cuban girlfriend, at long last.

Gaby and Laura were our perfect ambassadors to Cuba <strong>for</strong> three reasons. First, they were<br />

extremely excited that this trip was even taking place: it was a small miracle that all of Gaby’s best<br />

friends in college decided to fly to Cuba and experience Gaby’s new home. Second, Laura had lived<br />

in Havana her whole life, and Gaby was a Sagittarius like me, which meant she was a master of<br />

travel and exploration. Their collective mental map of the city was studded with a commendable<br />

constellation of dive bars, breakfast cafés, and cultural sites.<br />

Gaby and Laura were waiting <strong>for</strong> us with a yellow taxi van when we exited La Havana<br />

International. We all squinted our eyes reflexively, having zoomed from a 40-degree chill in North<br />

Carolina to 80 degrees of direct sunshine.<br />

On our taxi ride through the outskirts of Havana, everyone was hypnotized by the view<br />

through the rose-tinted windows. Everywhere I looked was cinematic. Men wearing only gym<br />

shorts and flip flops smoked cigarettes on the balconies of magnif<strong>ice</strong>nt old mansions, with mint<br />

green gilded facades and patches of disintegrated plaster. A small gray-haired woman rested on a<br />

park bench and sprinkled r<strong>ice</strong> on the ground <strong>for</strong> the street cats swarming at her feet. A lady in a<br />

bright blue dress rolled a wooden wagon full of fresh-cut flowers in every color down the uneven<br />

cobblestone streets.<br />

But the very first thing I not<strong>ice</strong>d took me completely by surprise: picturesque vintage cars<br />

everywhere. We passed a parking lot where each and every space was occupied by a hot pink<br />

convertible.<br />

When Americans think of Cuba, they visualize old cars. We imagine an entire rainbow fleet<br />

of Beetles and Bugs and Volkswagens. Based on their camera rolls, it seems like all tourists and<br />

visiting photographers encounter a lime green punch-buggie around every corner. I, a selfdescribed<br />

“woke traveler,” had rolled my eyes at these images. How basic, how reductive, how<br />

cliché!<br />

2

“Raise your hand if you’re surprised that there are actually this many vintage cars in Cuba!” I<br />

exclaimed, turning towards my friends in the backseat. They stared back at me unphased.<br />

“I’m surprised at how many new cars there are,” said Keely, pointing out the 90s-era sedans<br />

stopped at a red light. When and how had automobile imports restarted, she wondered? An<br />

interesting question— the first of hundreds that we would ask about our unfamiliar surroundings.<br />

But our phones never had serv<strong>ice</strong>, and we never bought public Wifi-access cards that Cubans use to<br />

connect to the internet in parks and town squares. Estranged from Google and Siri, my friends and I<br />

were emerging into what we named “post-truth society.” The answer to any question was simply<br />

whatever you thought might be the answer.<br />

From the very beginning of that initial taxi ride into Havana, I was filled with a yearning to<br />

know this place. I wanted to live there on this strange Caribbean island long enough to feel like I did<br />

about Mexico after I created my own world there <strong>for</strong> six months. As if I belonged, and understood,<br />

and could recognize these streets and these landmarks and these people.<br />

---<br />

That first day in Havana was hot. Walking around the city <strong>for</strong> the first time in the late<br />

afternoon, we darted to the shady side of each street <strong>for</strong> temporary relief from the heat. Gaby and<br />

Laura led the way: sometimes holding hands, sometimes turning to us to gesture at a notable<br />

landmark and offer at tour-guide spiel. The U.S. Embassy, menacing and ugly, isolated by the ocean<br />

and challenged by a long plaza to its north called “Anti-imperialist park.” The house Gaby first lived<br />

in when she studied abroad at the University of Havana sophomore year. Laura’s favorite spot <strong>for</strong><br />

cheap student food (cheesy pizza or ham-and-cheese sandwiches).<br />

I kept giving Ana and Keely looks as we strolled behind the couple. It was the first time we<br />

had ever seen them together, a real-life incarnation of their stunning Instagram portraits. We’d all<br />

3

known Gaby <strong>for</strong> years, and to finally witness her with the girl of her dreams left us all “awwwww”-<br />

ing at one another like a row of moms at their wedding ceremony.<br />

But while Cuba was a fever dream of off-the-beaten-path global experiences to us, Gaby and<br />

Laura had actual lives in Havana. A job. School. Apartment-hunting. Our intrepid American clique<br />

had to fend <strong>for</strong> ourselves <strong>for</strong> at least part of every day. After taking us to devour 50-cent pizzas at a<br />

popular student haunt, Gaby and Laura taxied away to continue their search <strong>for</strong> an apartment to<br />

move into together. It was 4 p.m. and here we were. In Cuba, sans our Cuban guides.<br />

Uncom<strong>for</strong>tably hot and stuffed with pizza, wondering aloud about the currency conversion and<br />

how we didn’t expect the street food to be so… Italian. I felt a familiar giddiness tugging my lips into<br />

a smile: we were on our own in a brand-new place, with nothing to do but explore!<br />

From our table outside the café, we could see the mysterious white concrete curves of a vast<br />

building of some kind through the trees of the park nearby.<br />

“Is that Coppelia?” asked Luke. Gaby and Laura had told us we were close to one of Havana’s<br />

most popular landmarks, the official <strong>ice</strong> <strong>cream</strong> headquarters of the state.<br />

“YES!” I said, a little too loudly, thrilled about what I had heard about this place called<br />

Coppelia. An authentic Cuban <strong>ice</strong> <strong>cream</strong> experience was my only goal <strong>for</strong> the entire trip.<br />

My sweet tooth is the stuff of friendly legend. For my twentieth birthday last year, my<br />

friends taped Smarties and lollipops all over the walls of our house. For my twenty-first this year, I<br />

feasted upon not one but three birthday cakes. I’m not sure how or when loving sugar became an<br />

assigned aspect of my identity, but it probably originated with my longest standing personality trait:<br />

the tendency to exaggerate. Sometimes I roll my eyes when my friends tease me about my adoration<br />

of dessert, but even if it’s a bit hyperbolic, I certainly never complained about the bottomless candy<br />

supply in my backpack <strong>for</strong> six straight weeks after my birthday. Much to my delight, Cubans seemed<br />

to appreciate sweet treats just as much as me.<br />

4

The legendary Coppelia squats magnif<strong>ice</strong>ntly over an entire city block in Vedado, a<br />

neighborhood about a twenty-minute walk from the regal University of Havana and the pastel<br />

babbling waterfall of commerce and tourists in Old Havana. Coppelia’s benevolent reign over the<br />

citizens of Cuba began in 1966 as a personal project of Fidel Castro and his right-hand-woman Celia<br />

Sánchez. Historical mythology holds that Castro was a devoted <strong>ice</strong> <strong>cream</strong> lover. He once ordered his<br />

Canadian ambassador to ship him every flavor of Howard Johnson’s <strong>ice</strong> <strong>cream</strong>; after sampling all<br />

twenty-eight containers, he made it his personal mission <strong>for</strong> Cuba to develop an <strong>ice</strong> <strong>cream</strong> culture<br />

to rival the American companies. Cuba would have the best frozen treats in all of the Caribbean,<br />

and thanks to the Revolution, it would be accessible to all.<br />

In the first several years after the Revolution, Castro and his revolutionary government<br />

tried to reverse the steep socioeconomic divide and social insecurity sown by the authoritarian<br />

regime they’d overthrown. The re<strong>for</strong>ms that the new thirty-something-year-old state authorities<br />

gallantly unleashed on Cuba sound fantastically utopian: elegant mansions taken from rich owners<br />

and turned over to the renters, farmland distributed to the farmers who worked it, free universal<br />

healthcare. Castro’s revolutionary Robin Hood government preached socialist progressive ideals of<br />

equality, just<strong>ice</strong>, internationalism and anti-imperialism.<br />

But the island utopia had powerful enemies. The U.S. president refused to meet with Castro<br />

when he visited the states soon after taking power; the U.S. cut diplomatic ties with Cuba and<br />

imposed a trade embargo in 1962, shoving in a damaging wedge between the nations that blocks<br />

any kind of mutually beneficial relationship; it has endured <strong>for</strong> five decades. Though most<br />

Americans have only heard of Bay of Pigs, the CIA launched many other missions to undermine<br />

their closest enemy: dropping swine flu and dengue fever on the island, bombing a department<br />

store, separating Cuban children from their families and adopting them into American families.<br />

While feuding with their antagonistic neighbor from above, Cuba needed economic support<br />

and imported goods to supplement the limited production and weak economy of the small<br />

5

Caribbean island. It willingly nestled under the Soviet wing. For the first time, Castro replaced his<br />

label of “revolutionary” and “socialist” with “communist.”<br />

And so it was until the 1990s, when the Soviet Bloc collapsed, and Cuba’s chief trading<br />

partners and financial support suddenly dropped out from underneath them. This was the catalyst<br />

that began the “Special Period”: more than ten years of scarcity and austerity.<br />

Older Cubans swear that Coppelia’s <strong>ice</strong> <strong>cream</strong> has never been the same since the economic<br />

crisis of the Special Period. Cuba’s limited bovine population could only make so much milk, and<br />

without powdered milk from East Germany and butter from the Soviet Union, the official state <strong>ice</strong><br />

<strong>cream</strong> <strong>for</strong>mula must have suffered. But Coppelia never once ceased to dish out sweet, indulgent<br />

ensaladas. Official grocery rations no longer included bottled milk, but Cubans could join the evergrowing<br />

lines outside of Coppelia and enter a sanctuary unlimited by shortage or rations; scoops of<br />

<strong>ice</strong> <strong>cream</strong> were always subsidized into costs so low that 10 scoops is the normal order. Even if it’s<br />

not as <strong>cream</strong>y as the original. Inside Coppelia, the Revolution is still a utopia. Beneath a Celia<br />

Sánchez quote, communal tables are shared, pr<strong>ice</strong>s are subsidized, long lines are enjoyed with goodnatured<br />

socializing. Most Cubans earn somewhere around $30 a month (the state salary), so it is<br />

unlikely that they can af<strong>for</strong>d to go out to the cafes and restaurants and bars where the cheapest item<br />

on the menu costs a day’s wages. Eat out at the <strong>ice</strong> <strong>cream</strong> cathedral, however, and ten scoops will<br />

run you less than 40 cents.<br />

---<br />

Coppelia resembles the unique Cuban architecture of many state-owned buildings sprinkled<br />

throughout Havana. U.S. cities are pointy, tall, and shiny, built out of sharp-angled steel; but metal<br />

materials like steel beams are scarce in Cuba, and the alternative cityscape looks whimsical and retro<br />

in comparison. Coppelia is constructed from concrete, all rounded angles and curved lines; thick<br />

concrete columns painted bright white and royal blue <strong>for</strong>m an open-air rotunda, supporting a raised<br />

6

central pavilion in the middle of the complex. A fat, snail-like spiral staircase winds down from this<br />

interior chamber to the main outdoor sections. The whole <strong>ice</strong> <strong>cream</strong> spaceship is split into five<br />

individual seating sections. Each section has its own queue snaking along the sidewalks outside the<br />

park.<br />

“Último?” asked a woman in her thirties who had appeared near one of Coppelia’s five<br />

entrance lines and now approached the parade of Cubans leaning against the park fence. Shades of<br />

skin colors in Havana range from porcelain white to deep ebony, and this woman was a deeply<br />

tanned bronze with blonde highlights in her dark brown hair. She was clad in characteristic Havana<br />

fashion: a hot pink tank top stretching skin-tight around the furrows of her belly, zebra print<br />

spandex shorts, yellow flip flops, and big dark sunglasses.<br />

A couple of teenage boys wearing large flashy sneakers and striped short-sleeve polo shirts<br />

gave the woman a wave and a nod.<br />

“Gracías!” said the woman, and she claimed a spot along the fence near the boys. She now<br />

knew who was el último— the last in line— and she could wait wherever she wanted, simply falling<br />

in line behind the boys when the somber security guards ushered a new wave of people into the<br />

blessed shade of the inner Coppelia courtyard.<br />

“Último” is the ritualistic refrain of Cuban line culture. And in a society where queuing up is<br />

a requisite of daily life, “line culture” really matters. If I lived in Havana I’d swelter in long sidewalk<br />

queues <strong>for</strong> my weekly grocery rations at the public grocery store; <strong>for</strong> switching colorful bills<br />

between the two official currencies at the money-exchange kiosk; and <strong>for</strong> ballet shows at the public<br />

theater.<br />

The subtle complexities of line etiquette were lost on me when I first attempted to visit<br />

Coppelia with my gangly gaggle of gringos. We walked right into the park, as confused as a huddle<br />

7

of penguins wandering the white concrete columns. Why were there were so many people milling<br />

about outside the park gates. Surely those weren’t the lines? Why would there be so many lines, so<br />

far away from the entrance? Fifty feet from the serene roped-in seating areas where tables of<br />

Cubans ordered their <strong>ice</strong> <strong>cream</strong> salads, three glowering security guards called us out. “CUC?” they<br />

asked. They wanted to know if we were using the expensive tourist currency. We conferred<br />

between ourselves, and told them yes, we had CUC.<br />

They led us to an out=of-the-way iron spiral staircase guarded by a bored looking woman.<br />

Upstairs was a small room with orange walls, too many tables, and a single counter manned by a<br />

man in an apron. He stood up when we entered, and handed me a laminated menu.<br />

The <strong>ice</strong> <strong>cream</strong> was $3.50 CUC! Which was about $4 in U.S. dollars! That couldn’t be right.<br />

The whole point of Coppelia was cheap <strong>ice</strong> <strong>cream</strong>. Dismayed, I turned around and ushered<br />

everyone back out of the door and down the staircase. It seemed that our first attempt was a failure;<br />

we should have told the security men that we wanted to pay with moneda nacional, Cuban<br />

currency, and not CUC.<br />

This time around, after I explained to the guards that we did have monedas, we were<br />

pointed towards a languishing sidewalk line and we took our place. We didn’t know if we were in<br />

the right place or how long we should wait, but I was determined to have a taste of that <strong>ice</strong> <strong>cream</strong> I<br />

glimpsed inside, so I made everyone take a seat on the curb.<br />

I would describe finally entering the center of the Coppelia park as a spiritual experience. A<br />

canopy of banyan trees cooled the pavement below, and after <strong>for</strong>ty-five minutes waiting on the<br />

sunny sidewalk, the speckled shade was as luscious as air conditioning. The couples and families and<br />

solitary diners tucking into their <strong>ice</strong> <strong>cream</strong> were quiet; a happy hush enshrouded the courtyard.<br />

The impressive size of the premises combined with this still reverence explains Coppelia’s common<br />

nickname: <strong>ice</strong> <strong>cream</strong> cathedral. I’m not religious, but I would worship at the <strong>ice</strong> <strong>cream</strong> cathedral<br />

seven days a week.<br />

8

I gazed around me at the bustling scene, an involuntary grin stretching across my sweaty<br />

face. Children, teenagers, adults, and elderly men and women sat at black iron patio tables or<br />

queued up in a patient line nearby to await a stool at the lengthy half-moon shaped counter inside<br />

the pavilion. Waiters ranging in apparent age from sixteen to twenty-five wore black shirts beneath<br />

plain white aprons and strode self-assuredly between tables and the kitchen, repeating customer<br />

requests back to each table: una copa de coco, dos de fresa, una ensalada, gracias.<br />

I saw other tables gliding spoons into sl<strong>ice</strong>s of a delicious, moist pie something, and I<br />

wondered how much one would cost. Did we have enough Cuban pesos to split one?<br />

As we awaited our waiter we watched a portly man in a graphic t-shirt and shades spoon<br />

innumerable scoops into a round silver bucket on his table.<br />

“Where did that even come from?!” asked Luke.<br />

“I wonder if he brought that himself,” said Keely, looking on in admiration as the man ladled<br />

melting <strong>ice</strong> <strong>cream</strong> into his to-go bucket. I would see a few more people do this on other visits to<br />

Coppelia; yes, in fact, they did bring their own vessels <strong>for</strong> take-out helados.<br />

“Hola buenos días, qué te traigo?” A handsome man appeared by our table and asked briskly <strong>for</strong><br />

our order. One by one, in varying degrees of Spanish competency, we asked <strong>for</strong> our flavors of<br />

cho<strong>ice</strong>. I eagerly asked <strong>for</strong> three, and everyone else ordered just one. The waiter furrowed his brow<br />

when we asked <strong>for</strong> single-scoops, but he hurried away regardless and was back with our frozen<br />

treats in three minutes flat.<br />

The <strong>ice</strong> <strong>cream</strong> was <strong>cream</strong>y, sugary sweet, and deliciously cold. The cookie crumb topping<br />

was a lovely touch. Our spoons flew as we licked our lips.<br />

When the waiter returned so that we could pay our bill, I asked <strong>for</strong> our total.<br />

“Nueve,” he said. Nine.<br />

9

“Yes, I know we had nine scoops, but what is the total bill <strong>for</strong> all of that?” I asked in Spanish.<br />

“Nueve,” he said again. I was confused; maybe my accent wasn’t so good after all. I tried to<br />

clarify again, but Luke interrupted.<br />

“Wait. I think it really is actually just nine monedas <strong>for</strong> everything. Didn’t Laura say<br />

Coppelia was the equivalent of 4 cents a scoop?”<br />

He was right. We couldn’t believe it. All of that <strong>ice</strong> <strong>cream</strong> we had just devoured, <strong>for</strong> only<br />

nine monedas? A handful of change? Two quarters?<br />

another round.<br />

As the magic of Coppelia dawned on us, we all began to laugh. And we immediately ordered<br />

---<br />

Coppelia line.<br />

One week later, on a cool Sunday evening, I strode up the sidewalk towards that block’s<br />

“Último?” I asked.<br />

“Yo,” answered a ten-year-old girl with two young friends, one hanging off the park gate<br />

and one sitting on the curb. She looked at me curiously, amused by the <strong>for</strong>eigner casually joining the<br />

local Cuban routine. I smiled at her and joined the line behind them.<br />

I was on my own, finding a spot to queue up and wait while the rest of my friends returned<br />

to our beloved JKL <strong>for</strong> pizza to quiet their rumbling bellies. I hadn’t eaten lunch either, but I wanted<br />

to save room <strong>for</strong> <strong>ice</strong> <strong>cream</strong> glory. This would be our very last visit to Coppelia; it was our last full<br />

day in Cuba.<br />

Which section of the cathedral was this line <strong>for</strong>? I hoped it would be the counter stools,<br />

reminiscent of a 1940s soda shop. City life was at a happy Sunday peak: loud ancient taxis and buses<br />

scooting down the street, a long line winding out of the currency conversion shop, groups of<br />

10

Cubans milling about in front of the liquor store and the theater and the other <strong>ice</strong> <strong>cream</strong> shop<br />

(where you could get helado <strong>for</strong> 20 times more than Coppelia but didn’t have to wait). A welldressed<br />

couple—rhinestone hoop earrings and fuchsia lipstick on her, showy red sneakers on him<br />

and a stud in his ear— strutted down the block and called <strong>for</strong> the Ultimo. I answered, and a few<br />

fellow line-waiters pointed to me. The fuschia-lipped girl, probably about my age, looked at me<br />

with skeptical disdain but moved behind me. Thirty minutes later, after the rest of my friends<br />

joined two-by-two, they snaked around in front of me. I really didn’t blame them <strong>for</strong> cutting seven<br />

Americans and their two Cuban friends.<br />

Querida Coppelia, Nunca podría expresar que tan agradecida estoy por poder disfrutar este paradiso<br />

único! Dear Coppelia: I could never express just how grateful I am to be able to enjoy this unique<br />

paradise!<br />

So begins the love letter I wrote to Cuba’s national <strong>ice</strong> <strong>cream</strong> cathedral as I reclined within<br />

its sacred premises <strong>for</strong> the last time. I left the absurd little note on the table, sticky from drips of<br />

melted <strong>ice</strong> <strong>cream</strong>. We all devoured our scoops of strawberry, coconut, and mantecada helados in<br />

record time, racing the 5-o-clock Cuban heat to clear our plastic orange <strong>ice</strong> <strong>cream</strong> boats.<br />

Inside Coppelia, the dream of a revolutionary society is still alive. The stillness and<br />

sweetness accessible to all is unlike anything I will ever encounter in my own fast-paced,<br />

competition-obsessed country. The system of lines and norms and culture was incomprehensive at<br />

first, but we learned, and we were enchanted. Jose Martí: “Charm is a product of the unexpected.”<br />

11