Angelus News | July 19-26, 2019 | Vol. 4 No. 26

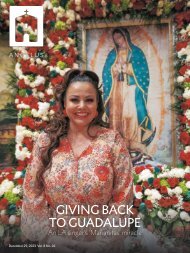

A 12th-century Byzantine mosaic depicts the Gospel story of Jairus asking Jesus to heal his dying 12-year-old daughter. For two millennia, the Catholic Church has been in the business of treating spiritual ailments — but that doesn’t mean it’s ignored people’s physical ailments. In fact, the world has Christianity and its founder to thank for some of the foundational principles of modern medicine. On Page 10, contributing editor Mike Aquilina tells the story of how the countercultural beliefs of early Christians led to one of society’s greatest inventions, the hospital. On Page 14, Angelus’ R.W. Dellinger tells the story of how a home hospice nurse is living out Jesus’ healing imperative by accompanying patients in their final moments.

A 12th-century Byzantine mosaic depicts the Gospel story of Jairus asking Jesus to heal his dying 12-year-old daughter. For two millennia, the Catholic Church has been in the business of treating spiritual ailments — but that doesn’t mean it’s ignored people’s physical ailments. In fact, the world has Christianity and its founder to thank for some of the foundational principles of modern medicine. On Page 10, contributing editor Mike Aquilina tells the story of how the countercultural beliefs of early Christians led to one of society’s greatest inventions, the hospital. On Page 14, Angelus’ R.W. Dellinger tells the story of how a home hospice nurse is living out Jesus’ healing imperative by accompanying patients in their final moments.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

Christianity’s healthiest idea<br />

The untold story of how<br />

the Church invented<br />

the hospital — and<br />

redefined health<br />

care in the process<br />

BY MIKE AQUILINA / ANGELUS<br />

SHUTTERSTOCK<br />

The hospital arose as a Christian<br />

institution utterly dependent<br />

upon Christian principles.<br />

The foremost expert on the early history<br />

of hospitals, Gary Ferngren, Ph.D.,<br />

made the point most emphatically in<br />

his recent historical survey published<br />

by Johns Hopkins University. He wrote:<br />

“The hospital was, in origin and conception,<br />

a distinctively Christian institution,<br />

rooted in Christian concepts of<br />

charity and philanthropy. There were<br />

no pre-Christian institutions in the<br />

ancient world that served the purpose<br />

that Christian hospitals were created<br />

to serve. … <strong>No</strong>ne of the provisions for<br />

health care in classical times … resembled<br />

hospitals as they developed in the<br />

late fourth century.”<br />

It’s not that there was no one practicing<br />

medicine. What passed for<br />

the medical profession was a riot of<br />

different types of practitioner. Many<br />

took up some strain of the Hippocratic<br />

tradition, but others were herbalists,<br />

soothsayers, magicians, or folk healers.<br />

There was no board to certify anyone.<br />

There were no medical schools to<br />

grant diplomas. Most professional healers<br />

simply underwent an apprenticeship<br />

with someone more experienced.<br />

Many practitioners made their living<br />

by wandering from town to town, perhaps<br />

outrunning the public response to<br />

their latest failures. Some made their<br />

way across continents this way.<br />

From the wisecracks we find in the<br />

Bible and other ancient literature, it<br />

seems that sick people understood<br />

that it was a risky proposition to seek<br />

healing. Medicine in the first centuries<br />

A.D. was an uncertain and unstable<br />

business.<br />

Why? Well, the wandering “medici”<br />

(“doctors”) had no roots, no local loyalties,<br />

no lasting accountability. They<br />

had no institutional form because there<br />

was no institutional form available to<br />

them.<br />

The Greeks and Romans had temples<br />

of Asclepius, where sick people went<br />

to pray and offer sacrifice in hope of<br />

a cure. Treatment in such places was<br />

usually based on the interpretation of<br />

dreams dreamt by the sick during a<br />

time of incubation in the sanctuary.<br />

While the Asclepian temples may<br />

have provided some occasional relief,<br />

they were not hospitals. They kept no<br />

long-term patients. They offered no<br />

extended program of treatment on site.<br />

The nearest approximation of a<br />

hospital in classical antiquity was the<br />

“valetudinarium” (“hospital”), which<br />

was essentially a repair shop for soldiers<br />

or slaves.<br />

Both soldiers and slaves represented<br />

huge investments for their overseers.<br />

Their value was expected to last years<br />

and even decades. And so the ancients<br />

established places where their human<br />

property could be restored to productivity.<br />

As far as we know, the Romans never<br />

entertained the idea of providing “valetudinaria”<br />

for the wider population.<br />

It’s difficult to see how they could have<br />

made one profitable or even sustainable.<br />

And yet there was great demand<br />

for medical care. Pain, sickness, and<br />

10 • ANGELUS • <strong>July</strong> <strong>19</strong>-<strong>26</strong>, 20<strong>19</strong>