Angelus News | July 19-26, 2019 | Vol. 4 No. 26

A 12th-century Byzantine mosaic depicts the Gospel story of Jairus asking Jesus to heal his dying 12-year-old daughter. For two millennia, the Catholic Church has been in the business of treating spiritual ailments — but that doesn’t mean it’s ignored people’s physical ailments. In fact, the world has Christianity and its founder to thank for some of the foundational principles of modern medicine. On Page 10, contributing editor Mike Aquilina tells the story of how the countercultural beliefs of early Christians led to one of society’s greatest inventions, the hospital. On Page 14, Angelus’ R.W. Dellinger tells the story of how a home hospice nurse is living out Jesus’ healing imperative by accompanying patients in their final moments.

A 12th-century Byzantine mosaic depicts the Gospel story of Jairus asking Jesus to heal his dying 12-year-old daughter. For two millennia, the Catholic Church has been in the business of treating spiritual ailments — but that doesn’t mean it’s ignored people’s physical ailments. In fact, the world has Christianity and its founder to thank for some of the foundational principles of modern medicine. On Page 10, contributing editor Mike Aquilina tells the story of how the countercultural beliefs of early Christians led to one of society’s greatest inventions, the hospital. On Page 14, Angelus’ R.W. Dellinger tells the story of how a home hospice nurse is living out Jesus’ healing imperative by accompanying patients in their final moments.

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

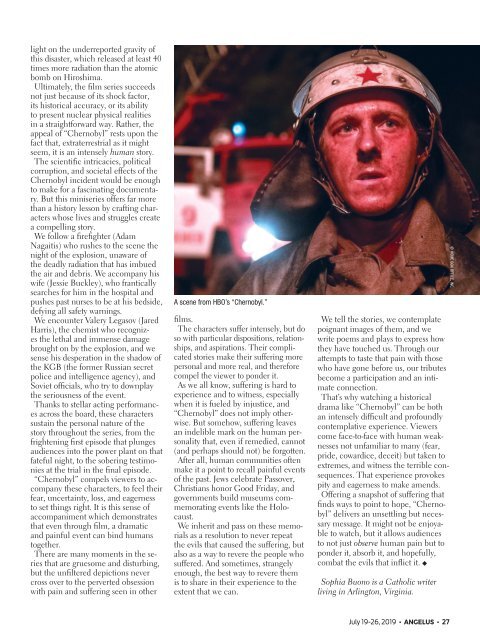

light on the underreported gravity of<br />

this disaster, which released at least 40<br />

times more radiation than the atomic<br />

bomb on Hiroshima.<br />

Ultimately, the film series succeeds<br />

not just because of its shock factor,<br />

its historical accuracy, or its ability<br />

to present nuclear physical realities<br />

in a straightforward way. Rather, the<br />

appeal of “Chernobyl” rests upon the<br />

fact that, extraterrestrial as it might<br />

seem, it is an intensely human story.<br />

The scientific intricacies, political<br />

corruption, and societal effects of the<br />

Chernobyl incident would be enough<br />

to make for a fascinating documentary.<br />

But this miniseries offers far more<br />

than a history lesson by crafting characters<br />

whose lives and struggles create<br />

a compelling story.<br />

We follow a firefighter (Adam<br />

Nagaitis) who rushes to the scene the<br />

night of the explosion, unaware of<br />

the deadly radiation that has imbued<br />

the air and debris. We accompany his<br />

wife (Jessie Buckley), who frantically<br />

searches for him in the hospital and<br />

pushes past nurses to be at his bedside,<br />

defying all safety warnings.<br />

We encounter Valery Legasov (Jared<br />

Harris), the chemist who recognizes<br />

the lethal and immense damage<br />

brought on by the explosion, and we<br />

sense his desperation in the shadow of<br />

the KGB (the former Russian secret<br />

police and intelligence agency), and<br />

Soviet officials, who try to downplay<br />

the seriousness of the event.<br />

Thanks to stellar acting performances<br />

across the board, these characters<br />

sustain the personal nature of the<br />

story throughout the series, from the<br />

frightening first episode that plunges<br />

audiences into the power plant on that<br />

fateful night, to the sobering testimonies<br />

at the trial in the final episode.<br />

“Chernobyl” compels viewers to accompany<br />

these characters, to feel their<br />

fear, uncertainty, loss, and eagerness<br />

to set things right. It is this sense of<br />

accompaniment which demonstrates<br />

that even through film, a dramatic<br />

and painful event can bind humans<br />

together.<br />

There are many moments in the series<br />

that are gruesome and disturbing,<br />

but the unfiltered depictions never<br />

cross over to the perverted obsession<br />

with pain and suffering seen in other<br />

A scene from HBO’s “Chernobyl.”<br />

films.<br />

The characters suffer intensely, but do<br />

so with particular dispositions, relationships,<br />

and aspirations. Their complicated<br />

stories make their suffering more<br />

personal and more real, and therefore<br />

compel the viewer to ponder it.<br />

As we all know, suffering is hard to<br />

experience and to witness, especially<br />

when it is fueled by injustice, and<br />

“Chernobyl” does not imply otherwise.<br />

But somehow, suffering leaves<br />

an indelible mark on the human personality<br />

that, even if remedied, cannot<br />

(and perhaps should not) be forgotten.<br />

After all, human communities often<br />

make it a point to recall painful events<br />

of the past. Jews celebrate Passover,<br />

Christians honor Good Friday, and<br />

governments build museums commemorating<br />

events like the Holocaust.<br />

We inherit and pass on these memorials<br />

as a resolution to never repeat<br />

the evils that caused the suffering, but<br />

also as a way to revere the people who<br />

suffered. And sometimes, strangely<br />

enough, the best way to revere them<br />

is to share in their experience to the<br />

extent that we can.<br />

We tell the stories, we contemplate<br />

poignant images of them, and we<br />

write poems and plays to express how<br />

they have touched us. Through our<br />

attempts to taste that pain with those<br />

who have gone before us, our tributes<br />

become a participation and an intimate<br />

connection.<br />

That’s why watching a historical<br />

drama like “Chernobyl” can be both<br />

an intensely difficult and profoundly<br />

contemplative experience. Viewers<br />

come face-to-face with human weaknesses<br />

not unfamiliar to many (fear,<br />

pride, cowardice, deceit) but taken to<br />

extremes, and witness the terrible consequences.<br />

That experience provokes<br />

pity and eagerness to make amends.<br />

Offering a snapshot of suffering that<br />

finds ways to point to hope, “Chernobyl”<br />

delivers an unsettling but necessary<br />

message. It might not be enjoyable<br />

to watch, but it allows audiences<br />

to not just observe human pain but to<br />

ponder it, absorb it, and hopefully,<br />

combat the evils that inflict it. <br />

Sophia Buono is a Catholic writer<br />

living in Arlington, Virginia.<br />

© HOME BOX OFFICE, INC.<br />

<strong>July</strong> <strong>19</strong>-<strong>26</strong>, 20<strong>19</strong> • ANGELUS • 27