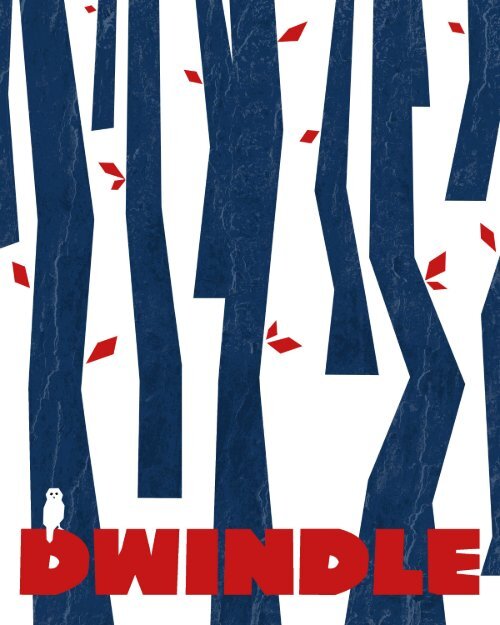

Dwindle Book Project

A collection of vulnerable and near threatened animal species, a graphic design project

A collection of vulnerable and near threatened animal species, a graphic design project

You also want an ePaper? Increase the reach of your titles

YUMPU automatically turns print PDFs into web optimized ePapers that Google loves.

Copyright © 2019 by Alyssa Clayton<br />

All rights reserved. This book or any portion thereof<br />

may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever<br />

without the express written permission of the publisher<br />

except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.<br />

Printed in the United States of America<br />

First Edition

DWINDLE<br />

A COLLECTION OF VULNERABLE AND NEAR<br />

THREATENED ANIMAL SPECIES<br />

Illustrated by Alyssa Clayton

ONTENTS

................................................................ 1<br />

........................................................... 4<br />

American Bison................................................. 6<br />

Cheetah........................................................ 8<br />

........................................................... 10<br />

Pacific Leatherback Sea Turtle ................................. 12<br />

Marine Iguana................................................ 14<br />

.............................................................. 16<br />

Spotted Owl .................................................. 18<br />

Wandering Albatross ......................................... 20<br />

.............................................................. 22<br />

Yellowfin Tuna................................................ 24<br />

Great White Shark ........................................... 26<br />

...................................................... 28<br />

Glass Frogs .................................................. 30<br />

California Tiger Salamander .................................. 32<br />

......................................................... 34<br />

...................................................... 36<br />

Intro<br />

Mammals<br />

Reptiles<br />

Birds<br />

Fish<br />

Amphibians<br />

End Notes<br />

Bibliography

I

NTRO<br />

What is happening to our species and their habitat?<br />

There is no doubt that a vast number of animals and plants<br />

have gone extinct in recent centuries due to human activity,<br />

especially since the industrial revolution. The number of<br />

individuals across species of plants and animals has declined<br />

as well – in many cases severely – affecting genetic variation,<br />

biodiversity, among other issues.<br />

All around the world, areas where humans exploit natural<br />

resources or undergo encroaching development all have the<br />

same outcome: a deteriorating natural environment. As a<br />

result of human action, ecosystems face threats such as<br />

unhealthy production and consumption; in today’s interconnected<br />

world, it doesn’t take much to see these unsustainable<br />

forces to take hold.<br />

This is a trend that cannot continue. If ecosystems are too<br />

severely depleted, their ability to remain replenish, sustain<br />

our species, and meet human needs is drastically threatened.<br />

Many of us have seen images depicting open prairies covered<br />

by massive herds of bison that no longer exist, enormous<br />

flocks of birds congregated in marshes and lagoons that have<br />

seen their numbers reduced dramatically, or beautiful and<br />

impressive animals such as elephants, giraffes, and whales,<br />

which — in many cases — are in danger of becoming extinct.<br />

Other people have cherished memories of less imposing<br />

animals that nonetheless bring deeply felt emotions, such<br />

as the sound of thousands of frogs croaking in the middle<br />

of the night, birds visiting a backyard feeder year after<br />

year, or millions of bats flying to their resting place at<br />

dusk. Others might remember that when traveling by car<br />

through the countryside, their car’s windshield ended up<br />

covered with hundreds of dead insects, which sadly was a<br />

signal of abundance that now hardly ever happens.<br />

If you lived close to the ocean or spent much time there, you<br />

have probably heard that fish stocks have declined dramatically<br />

or read stories about whales, dolphins, and other<br />

marine mammals washing up dead on beaches, occasionally<br />

in large numbers.<br />

In the last decades, we have learned countless stories of<br />

new species of plants or animals being discovered in tropical<br />

forests across the globe, giving us a sense of wonder and<br />

LET’S CHECK SOME NUMBERS:<br />

The number of animals living on the land<br />

has fallen by 40% since 1970.<br />

Marine animal populations have also fallen<br />

by 40% overall.<br />

Overall, 40 percent of the world’s 11,000<br />

bird species are in decline.<br />

Animal populations in freshwater ecosystems<br />

have plummeted by 75% since 1970.<br />

Insect populations have declined by 75% in<br />

some places of the world.<br />

possibility. At the same time, millions of acres of natural<br />

forests are being destroyed every year.<br />

About a quarter of the world’s coral reefs have already been<br />

damaged beyond repair, and 75 percent of the world’s coral<br />

reefs are at risk from local and global stresses.<br />

It is estimated that humans have impacted 83% of Earth’s<br />

land surface, which has affected many ecosystems as well as

the range in which specific species of wildlife used to exist.<br />

Developed nations have seen benefits in economic growth not<br />

only from the exploitation of their ecosystems and species,<br />

but from the exploitation of the ecosystems and species of<br />

undeveloped nations as well. Currently, the biggest declines<br />

in animal numbers are happening in low-income, developing<br />

nations, mirroring declines in wildlife that occurred in<br />

wealthier nations long before. The last wolf in the UK was<br />

killed in 1680. For instance, between 1990 and 2008, around<br />

a third of products that cause deforestation – timber, beef,<br />

and soya – were imported to the EU.<br />

Academics and others debate if we are already facing a new<br />

process of mass extinction, such as the ones the world has<br />

experienced over the millennia. But even if that is not the<br />

case, we know that thousands of species are endangered,<br />

and most land and sea flora and fauna have seen their<br />

numbers severely reduced, with few exceptions.<br />

Many species have disappeared already and many more are<br />

following the same path. As reported by The World Conservation<br />

Union (IUCN), there have been 849 species that have<br />

disappeared in the wild since 1500 A.D.; most strikingly,<br />

this number greatly underestimates the thousands of species<br />

that disappeared before scientists were able to identify<br />

them. Most troublingly, around 33% and 20% of amphibians<br />

and mammals are in danger of becoming extinct in the<br />

coming decades.<br />

We also know that some people have argued that species<br />

have disappeared before and how the current decline is just<br />

part of a natural process. But this conclusion is way off<br />

base. All other processes of global mass extinction in the<br />

history of the planet happened because of a catastrophic<br />

natural event. They were not the result of human intervention,<br />

as is the case for the current mass extinction.<br />

According to Peter Ward from the University of Washington,<br />

what we are experiencing today is strikingly similar<br />

to the dinosaur-killing event of 60 million years ago, when<br />

a planet already stressed by sudden changes in its climate<br />

was knocked into mass extinction by the impact of asteroids.<br />

This mass extinction we are going through has been<br />

unfolding because of the intervention of a single species, us.<br />

Humans are having an outsized negative impact on all other<br />

species. Human activity has caused a dramatic reduction<br />

in the total number of species and the population sizes of<br />

specific species; thousand have already disappeared, and<br />

many more are threatened with extinction.<br />

The marine extinction crisis is not as widely grasped as<br />

the crises in tropical forests and other terrestrial biomes.<br />

We do not know how many species are in the ocean as the<br />

bulk of marine species are undiscovered. Therefore, we do<br />

not know how many have disappeared or how many are in<br />

danger of disappearing. Furthermore, we are also losing<br />

species or unique types within a species (for example a type<br />

of salmon), before we even know of them.<br />

We know that overfishing is a major global concern. Current<br />

assessments cover only 20% of the world’s fish stocks, so<br />

the true state of most of the world’s fish populations is not<br />

clear. Although, recent findings suggest that those unstudied<br />

stocks are declining, and nearly three-quarters of the world’s<br />

commercially fished stocks are overharvested and at risk.<br />

Along with species extinction, the devastation of genetically<br />

unique populations and the loss of their genetic variation<br />

leads to an irreversible biodiversity loss. The evidence all<br />

points to the unfolding of a global tragedy with permanent<br />

consequences.<br />

What is driving this process of extinction? Overexploitation<br />

of species either for human consumption, use, elaboration<br />

of byproducts, or for sport.<br />

HABITAT DESTRUCTION:<br />

A bulldozer pushing down trees is the iconic image of habitat<br />

destruction. Other ways people directly destroy habitat<br />

include filling in wetlands, dredging rivers, mowing fields,<br />

and cutting down trees.<br />

HABITAT FRAGMENTATION:<br />

Much of the remaining terrestrial wildlife habitat has been<br />

cut up into fragments by roads and development. Aquatic<br />

species’ habitats have been fragmented by dams and water<br />

diversions. These fragments of habitat may not be large<br />

or connected enough to support species that need a large<br />

territory where they can find mates and food. Also, the<br />

loss and fragmentation of habitats makes it difficult for<br />

migratory species to find places to rest and feed along<br />

their migration routes.<br />

HABITAT DEGRADATION:<br />

Pollution, invasive species, and disruption of ecosystem<br />

processes (such as changing the intensity of fires in an<br />

ecosystem) are some of the ways habitats can become so<br />

degraded they can no longer support native wildlife.

CLIMATE CHANGE:<br />

As climate change alters temperature and weather patterns,<br />

it also impacts plant and animal life. Scientists expect that<br />

the number and range of species, which define biodiversity,<br />

will decline greatly as temperatures continue to rise.<br />

The burning of fossil fuels for energy and animal agriculture<br />

are two of the biggest contributors to global warming,<br />

along with deforestation. Livestock accounts for between<br />

14.5 percent and 18 percent of human-induced greenhouse<br />

gas emissions. Those emissions come from cattle belches,<br />

intestinal gasses, and waste; the fertilizer production for<br />

feed crops; general farm associated emissions; and the<br />

process of growing feed crops. According to research<br />

conducted by the Worldwatch Institute’s Nourishing the<br />

Planet project, animal waste releases methane and nitrous<br />

oxide, greenhouse gases that are much more potent than<br />

carbon dioxide. As people increase their level of income, they<br />

consume more meat and dairy products. The populations of<br />

industrial countries consume twice as much meat as those<br />

in developing countries. Worldwide meat production has<br />

tripled over the last four decades and increased 20 percent<br />

in just the last ten years. This information suggests that<br />

we should cut back on our consumption of meat and dairy.<br />

“The privilege we have over these animals, it would appear,<br />

now comes at a hefty price [to the planet].”<br />

The spread of non-native species around the world; a single<br />

species (us) taking over a significant percentage of the<br />

world’s physical space and production; and, human actions<br />

increasingly directing evolution.<br />

The first factor is also known as the global homogenization<br />

of flora and fauna. Biotic homogenization is an emerging,<br />

yet pervasive, threat in the ongoing biodiversity crisis. Originally,<br />

ecologists defined biotic homogenization as the replacement<br />

of native species by exotics or introduced species,<br />

but this phenomenon is now more broadly recognized<br />

as the process by which ecosystems lose their biological<br />

uniqueness and uniformity grows. As global transportation<br />

becomes faster and more frequent, it is inevitable that<br />

species intermixing will increase. When unique local flora<br />

or fauna become extinct, they are often replaced by already<br />

widespread flora or fauna that is more adapted to tolerate<br />

human activities. This process is affecting all aspects of<br />

our natural world. For example, we grow the same crops<br />

anywhere in the world at the expense of the local varieties<br />

that in many cases disappear; introduce animals into places<br />

where they did not exist, and often do not have natural<br />

enemies, becoming a plague, such as rats introduced to<br />

the Galapagos Islands; or destroy other species that cannot<br />

defend themselves from the new predator, such as in Guam<br />

where over the years ten of Guam’s twelve original forest<br />

bird species have been lost due to the introduction of the<br />

brown tree snake. Biological homogenization qualifies as<br />

a global environmental catastrophe. The Earth has never<br />

witnessed such a broad and complete reorganization of<br />

species distribution, in which animals and plants (and other<br />

organisms for that matter) have been translocated on a<br />

global scale around the planet.<br />

Over the last few centuries, humans have essentially become<br />

the top predator not only on land, but also across the sea. In<br />

doing so, humanity has begun using 25-40% of the planet’s<br />

net primary production for its own. As we keep expanding<br />

our use of land and resources, the capacity of species to<br />

survive is constantly reduced.<br />

Humanity has become a massive force in directing evolution.<br />

This is most apparent in the domestication of animals<br />

and the cultivation of crops over thousands of years. But<br />

humans are directing evolution in numerous other ways<br />

as well, manipulating genomes by artificial selection and<br />

molecular techniques, and indirectly by managing ecosystems<br />

and populations to conserve them, said co-author Erle<br />

Ellis, an expert on the Anthropocene with the University<br />

of Maryland. He added that even conservation is impacting<br />

evolution.<br />

In countries around the world, policies have been enacted<br />

that have led to extinction or near extinction of specific<br />

species, such large predators in the US and Europe. Also,<br />

chemical products associated with agriculture or other<br />

productive processes have affected many species such as<br />

honeybees and other pollinators.

HE GREAT<br />

MERICAN<br />

ISON<br />

BY JED PORTMAN<br />

MAY 3, 2011<br />

They show up on old nickels, on the backs of quarters and<br />

on flags. They surface in burgers and jerky, in the logos of<br />

sports teams and universities and in the names of towns<br />

and cities.<br />

A 2008 survey conducted by the Wilderness Conservation<br />

Society revealed that, while 74 percent of Americans polled<br />

agreed that bison are “extremely important living symbols<br />

of the American West,” and more than half agreed that<br />

bison are important symbols of our country as a whole,<br />

fewer than 10 percent had any idea how many bison are<br />

left in the country. Eighty-three percent of survey subjects<br />

believed that bison meat “was good or better than beef,”<br />

but only 40 percent had actually tried it. It’s hard to live<br />

in this part of the world without being a little bit familiar<br />

with the American bison, but how far beyond familiar does<br />

our knowledge extend?<br />

The average American bison – commonly referred to as the<br />

American buffalo — stands 5 to 6.5 feet tall and can weigh<br />

more than a ton. Despite that heft, bison can run at speeds<br />

of more than 30 miles per hour and execute standing jumps<br />

of up to 6 feet in the air. Yellowstone National Park warns<br />

its visitors to stay at least 25 yards away from all wild<br />

bison, and for good reason. These lumbering vegetarians<br />

have injured more Yellowstone tourists than any other<br />

animal in the park.<br />

The bison’s wild temperament and legendary stubbornness<br />

have frustrated more than a few wannabe wranglers. “You<br />

can herd a buffalo anywhere he wants to go” goes the<br />

saying among farmers and ranchers familiar with these<br />

imposing animals.<br />

The American bison, the largest land animal native to<br />

North America, prospered in the open grasslands of this<br />

country for centuries. Scientists estimate that there were<br />

more than 30 million bison in North America when the<br />

first European settlers arrived on the continent, grazing a<br />

vast range which ran from northern Canada to northern<br />

Mexico and from western New York to eastern Washington.<br />

“The amazing herds of buffaloes which resort thither, by<br />

their size and number, fill the traveller with amazement<br />

and terror,” wrote John Filson in 1784 of herds in northern<br />

Kentucky. The journals of Lewis and Clark described<br />

western herds “so numerous” that they “darkened the whole<br />

plains.”<br />

As late as 1871, a young soldier named George Anderson<br />

AMERICAN<br />

BISON<br />

SCIENTIFIC NAME:<br />

Bison bison<br />

SIZE: 5’- 6.5’ tall<br />

DIET: Herbivore<br />

FUN FACT: Bison are the largest mammals in North America,<br />

and bison calves typically weigh 30 - 70 pounds at birth.<br />

Until the 1700’s, Bison numbers<br />

used to be estimated around 30<br />

million in the US.

described an “enormous” herd of bison in Kansas which<br />

took he and his men six days to pass through. “I am safe<br />

in calling this a single herd,” he wrote, “and it is impossible<br />

to approximate the millions that composed it.”<br />

Hornaday and former president Theodore Roosevelt, were<br />

able to rescue the bison from its impending extinction.<br />

Today’s bison population is higher than 500,000 and steadily<br />

growing.<br />

A fatal combination of events came together against the<br />

bison in the second half of the 19th century. American<br />

Indian tribes acquired horses and guns and were able to<br />

kill bison in larger numbers than ever before. A drought<br />

dried out the animals’ grassland habitat, which was already<br />

overburdened by new populations of horses and cattle.<br />

Farmers and ranchers began killing bison to make room<br />

for their animals. Some soldiers killed bison to spite their<br />

American Indian enemies, who depended on the animals<br />

for food and clothing.<br />

Railroads were laid through the bison’s territory, dividing<br />

herds and accelerating the arrival of hunters, whose kills<br />

fed the high demand for bison hides back East and in<br />

Europe. Sport shooters traveled west to shoot the animals<br />

by the dozens, sometimes from the open windows of moving<br />

trains, and often left their bodies out on the plains to rot<br />

once the hunt was over.<br />

By the beginning of the 20th century, there were only<br />

several hundred bison left in North America.<br />

The efforts of early 20th century organizations like the<br />

American Bison Society, headed by zoologist William<br />

According to Texas A&M professor of veterinary pathobiology<br />

Dr. James Derr, though, most bison alive today are<br />

genetically different from their wild ancestors. At the low<br />

point of the bison population – what geneticists call the<br />

“bottleneck” – in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the<br />

ranchers who owned a lot of the remaining bison population<br />

bred their bison with cattle in an attempt to create better<br />

meat animals. “When people went looking for bison later,”<br />

said Derr, “they had to go to the private guys who owned<br />

them, and in many cases those private guys had been<br />

producing hybrids.”<br />

Derr has spent the past several decades analyzing bison<br />

DNA to determine which herds contain cattle genes, and<br />

believes that only about 1.6 percent of today’s bison population<br />

(8,000 animals) is not hybridized.<br />

And today’s bison don’t roam the plains like they used<br />

to, either. Only about 20,000 bison – 4 percent of the<br />

overall population – make up the wild herds that graze our<br />

national parks and private reserves. The other 96 percent<br />

are livestock animals, raised commercially for meat and<br />

hides.<br />

NEAR THREATENED<br />

AMERICAN BISON<br />

By 1884 there were 325<br />

wild bison left.<br />

Due to conservation efforts,<br />

as of 2017, there are around<br />

500,000 bison in the US.

The world’s fastest land mammal is racing toward extinction,<br />

with the latest cheetah census suggesting that the big<br />

cats, which are already few in number, may decline by an<br />

additional 53 percent over the next 15 years.<br />

“That’s really perilous,” says Luke Hunter, president and<br />

CCO for Panthera, the global wild cat conservation organization.<br />

“That’s a very active decline, and you have to really<br />

step in and act to address that.”<br />

Today there are just 7,100 cheetahs left in the wild, according<br />

to the new study, which appears this week in the<br />

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. That’s<br />

down from an estimated 14,000 cheetahs in 1975, when<br />

researchers made the last comprehensive count of the<br />

animals across the African continent, Hunter says.<br />

In addition, the cheetah has been driven out of 91 percent<br />

of its historic range—the big cats once roamed nearly all<br />

of Africa and much of Asia, but their population is now<br />

confined predominantly to six African countries: Angola,<br />

Namibia, Zimbabwe, Botswana, South Africa, and Mozambique.<br />

The species is already almost extinct in Asia, with<br />

fewer than 50 individuals remaining in one isolated pocket<br />

of Iran.<br />

Based on these results, the study authors are calling for<br />

the cheetah’s status to be changed from “vulnerable” to<br />

“endangered” on the IUCN Red List.<br />

“These large carnivores, when they are declining at that<br />

sort of rate, then extinction becomes a real possibility,”<br />

Hunter says.<br />

Perhaps unsurprisingly, humans are the main reason that<br />

cheetahs are in peril. Like other large carnivores, cheetahs<br />

face habitat loss driven by conversion of wilderness areas<br />

into managed land dedicated to agriculture or livestock.<br />

People will then sometimes kill cheetahs if they perceive the<br />

animals as a threat to their livestock, even though cheetahs<br />

rarely take domesticated animals, Hunter says.<br />

Cheetahs are also subject to vehicle collisions, poaching<br />

for their skin and other body parts, and even being killed<br />

for bushmeat, though that threat is mostly targeted at<br />

cheetah’s prey species, such as antelopes, gazelles, impalas,<br />

and warthogs. All are ideal cheetah prey, and all are heavily<br />

hunted by people in many areas, Hunter says.<br />

“Cheetahs are facing a double whammy: They are getting<br />

killed directly, and then also their prey species are getting<br />

killed in these savannah areas, so the cheetahs having<br />

nothing to subsist on,” Hunter says.<br />

Other threats include high demand for cheetah cubs as pets,<br />

mainly in the Middle East, which results in the illegal trade<br />

of cubs from North Africa.<br />

Some cheetahs already live in protected areas like national<br />

parks, where it is safer, more accessible, and the animals<br />

are expected to be subjected to fewer threats, says study<br />

leader Sarah Durant of the Zoological Society of London.<br />

But during the new assessment, Durant and her colleagues<br />

found that two-thirds of the cheetah population lives outside<br />

of these protected zones, in part because the animals need<br />

room to roam.<br />

“We can’t have any more cheetahs in protected areas ...<br />

the density is already the maximum it can be,” Durant<br />

says. “The key to the survival of the cheetah is its survival<br />

outside of protected areas.”<br />

The study team, led by Panthera, the Zoological Society of<br />

London, and the Wildlife Conservation Society, hope that<br />

their results will spur the IUCN to re-classify the cheetah<br />

as endangered.<br />

It is likely too late to grow and protect the species in<br />

areas like West or Central Africa, where these big cats<br />

have long been on the decline, Hunter adds. But there is<br />

enormous potential for the population to rebound quickly<br />

in other areas.<br />

HEETAHS ARE<br />

ANGEROUSLY<br />

LOSE TO<br />

BY ALEXANDRA E. PETRI<br />

DEC 27, 2016

The new conservation status would provide a platform<br />

for these groups to try and reverse the trends affecting<br />

cheetahs. For instance, such a change can create openings<br />

for funding streams that are available only to endangered<br />

species, and they might allow for conversations with African<br />

governments about cheetah conservation programs.<br />

and make sure we have the policy and financial<br />

policy framework in place so that they will<br />

benefit from conservation.”<br />

“What we are really hoping,” Durant says, “is this will<br />

catalyze action to start thinking outside the box for cheetah<br />

and landscape conservation, to start looking beyond the<br />

protected-area system and looking at how we<br />

can get communities engaged<br />

in and supportive of<br />

conservation,<br />

VULNERABLE<br />

CHEETAH<br />

CHEETAH<br />

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Acinonyx jubatus<br />

SIZE: 2’-3’ tall<br />

DIET: Carnivore<br />

FUN FACT: Cheetah’s are the only cat<br />

in the cat family whose claws don’t retract,<br />

specifically to help them have a better grip<br />

when running.

ACIFIC LEATHERBACK<br />

URTLES’ ALARMING<br />

ECLINE<br />

BY BECKY OSKIN<br />

FEB 27, 2013<br />

ONTINUES<br />

The Pacific leatherback turtle’s last population stronghold<br />

could disappear within 20 years if conservation efforts<br />

aren’t expanded, a new study finds.<br />

Most of the Pacific Ocean’s leatherback turtles, at least 75<br />

percent, lay their eggs at Bird’s Head Peninsula in Papua<br />

Barat, Indonesia. The number of leatherback turtle nests at<br />

the peninsula’s beaches dropped 78 percent between 1984<br />

and 2011, the study discovered.<br />

“If the decline continues, within 20 years it will be difficult<br />

if not impossible for the leatherback to avoid extinction,”<br />

Thane Wibbels, a biologist at the University of Alabama at<br />

Birmingham (UAB), said in a statement. “That means the<br />

number of turtles would be so low that the species could<br />

not make a comeback.”<br />

At Jamursba Medi Beach, on Bird’s Head Peninsula, nests<br />

fell from 14,455 in 1984 to a low of 1,532 in 2011, the study<br />

found. Because female turtles nest multiple times each year,<br />

the researchers estimate that 489 breeding females remain<br />

in the western Pacific leatherback population. Overall, the<br />

total turtle population dropped 5.9 percent each year since<br />

1984, the researchers estimate.The findings were published<br />

Feb. 27, 2013 in the journal Ecospheres.<br />

Leatherback sea turtles are the largest of all living turtles<br />

and are found throughout the world’s oceans. Their unique<br />

“leathery” shells can reach 6.5 feet (2 meters) in length and<br />

they weigh up to 1,190 pounds (540 kilograms).<br />

Although Atlantic populations have increased in recent<br />

years, the Pacific leatherback population has dropped more<br />

than 95 percent since the 1980s. The leatherback turtle was<br />

listed as endangered in the United States in 1970.<br />

Tapilatu, lead study author and a doctoral student at UAB,<br />

said in a statement.<br />

In the ocean, turtles are often victims of bycatch, unintentional<br />

netting and killing while fishing for other prey, as they<br />

travel through multiple fishing zones on their long migrations.<br />

Pacific leatherback turtles migrate from their nesting<br />

site in Indonesia to feeding grounds near the Americas.<br />

Environmental changes caused by the El Niño/La Niña<br />

climate oscillation may also have affected turtles by reducing<br />

their food sources, particularly jellyfish.<br />

Conservation efforts at Indonesia’s beaches include patrols<br />

by local residents to protect nests from predators and<br />

relocating eggs to areas with cooler sand. (The sand<br />

temperature influences the sex of hatchlings — cool sand<br />

means more male turtles.)<br />

But Tapilatu, a native of western Papua, Indonesia, who<br />

has worked on turtle conservation since 2004, said beach<br />

conservation alone is unlikely to tip the scales in favor of<br />

the recovery.<br />

“They can migrate more than 7,000 miles [11,000 kilometers]<br />

and travel through the territory of at least 20 countries,<br />

so this is a complex international problem,” Tapilatu said.<br />

In February 2012, the United States protected about 42,000<br />

square miles (108,800 square kilometers) of the Pacific<br />

Ocean off California, Oregon and Washington as critical<br />

habitat for leatherbacks.<br />

Much of the decline is due to humans. Before the practice<br />

was outlawed in 1993, villagers and fisherman collected<br />

turtle eggs by the thousands in Indonesia. Dogs and pigs<br />

still dig up turtle eggs along Bird’s Head’s beaches, Ricardo

If the decline continues, within 20 years<br />

it will be difficult if not impossible for<br />

the leatherback to avoid extinction.<br />

PACIFIC LEATHERBACK SEA TURTLE<br />

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Dermochelys coriacea<br />

SIZE: 6’-7’ long<br />

DIET: Omnivore<br />

FUN FACT: Unlike all other marine turtles, the<br />

leatherback turtle does not have a hard, bony shell.<br />

PACIFIC LEATHER-<br />

BACK SEA TURTLE<br />

VULNERABLE

ALAPAGOS MARINE<br />

GUANAS STRUGGLING<br />

GAINST TOURISTS,<br />

LACK RATS AND<br />

HE WEATHER<br />

BY BRIAN GROSS<br />

JUNE 15, 2015<br />

The marine iguana, a coal-black, prehistoric-looking creature<br />

found nowhere on earth but the Galapagos Islands, is coping<br />

with some difficult times.<br />

Its population has declined by several hundred thousand<br />

over the last 15 years, scientists estimate.<br />

“The town was flooded with iguanas when I was growing<br />

up,” said Lucas Tario, a 46-year-old baker who grew up in<br />

the Galapagos. “Now they’re not as easy to find.”<br />

In 1996, the International Union for Conservation of<br />

Nature, with headquarters in Switzerland, listed the marine<br />

iguana as vulnerable, one level below endangered. It said<br />

the iguanas reproduce slowly and confront many threats.<br />

Jenifer Suarez, a specialist on wildlife surveys at the Charles<br />

Darwin Research Center, said a study from 2004 to 2014<br />

at Punta Nunez, about 10 miles east of Puerto Ayora, the<br />

main town on the island of Santa Cruz, showed an 18.5<br />

percent decline from 3,200 marine iguanas to 2,609. As<br />

to what is causing the decline, the scientists are stumped.<br />

“We are not really sure,” said Suarez. Many theories are<br />

being bandied about, including changes in the weather,<br />

attacks by other animals and the growth of tourism.<br />

The weather phenomenon known as El Niño has always<br />

been tough on marine iguanas. El Niño causes warmerthan-usual<br />

ocean currents that kill algae, the main food<br />

of marine iguanas.<br />

as 20 percent by digesting parts of its own bones, scientists<br />

say. It is the only animal in the world with that capability.<br />

But that’s not enough.<br />

In the last two decades, the frequency of El Niño has<br />

doubled and that makes it harder for marine iguanas to<br />

recover from each episode.<br />

El Niño is also blamed for negatively affecting the marine<br />

iguanas breeding. In the 1982-83 El Niño cycle, as many<br />

as 70 percent of some varieties of marine iguanas died,<br />

scientists say.<br />

It’s not just the marine iguana whose numbers are down in<br />

the Galapagos. Population surveys indicate the blue-footed<br />

booby, the Galapagos sea lion and the Galapagos penguins<br />

have also been decreasing because of the El Niño phenomenon.<br />

Another explanation for the decline in marine iguanas<br />

might be the non-native animals that have been brought<br />

to the islands, either intentionally or unintentionally. As<br />

far back as the 17th Century, pirates and explorers used<br />

the Galapagos as a stop for fresh food and water. The<br />

descendants of the animals they had on the ships with<br />

them, such as goats, pigs and black rats, roam the islands<br />

today. These animals, plus the domesticated dogs and cats<br />

that have come along in recent decades, often snatch up<br />

the marine iguana eggs and newborns.<br />

The marine iguana has a one-of-a-kind survival technique.<br />

When food is short, it is able to shrink itself by as much

FUN FACT: Marine iguanas are coal black when they are<br />

young, but as they mature they change to more vibrant colors,<br />

especially the males during breeding seasons.<br />

Just how much damage the rats and other predatory animals<br />

have done is not clear. But the government has killed<br />

hundreds of thousands of goats and millions of black rats<br />

at a cost of millions of dollars.<br />

But a more recent intruder on the islands is affecting the<br />

iguanas: the tourist.<br />

MARINE<br />

IGUANA<br />

SCIENTIFIC NAME:<br />

Amblyrhynchus cristatus<br />

SIZE: 4’-5’ long<br />

DIET: Herbivore<br />

“The most common problem that we have, not only with<br />

the marine iguana, but with most animals, are that tourists<br />

want to touch them,” said Eduardo Espinoza, an iguana<br />

specialist at the Charles Darwin Research Station. The<br />

iguana’s stress levels spike when people touch them,<br />

Espinoza said.<br />

As recently as the 1960s, only a trickle of back-packers and<br />

a few yachtsmen and women were coming to the Galapagos<br />

Islands. In 1979, the government says, 12,000 tourists<br />

visited the Galapagos. In 2012, immigration officials counted<br />

180,000 tourists. And people who live in the Galapagos say<br />

they think well over 200,000 tourists are arriving annually<br />

now.<br />

But a more recent intruder<br />

on the islands is affecting<br />

the iguanas: the tourist.<br />

Much of the 51,000 square miles of volcanic islands and<br />

ocean in the Galapagos is still pristine. But stretches of<br />

Galapagos land that were once occupied only by marine<br />

iguanas, giant Galapagos tortoises and other animals have<br />

been taken over by restaurants, hotels, souvenir and snack<br />

shops, and scuba diving businesses.<br />

People from mainland Ecuador and elsewhere around the<br />

world are moving to the archipelago hoping to make money<br />

catering to the tourists.<br />

The community of people living in the Galapagos has grown<br />

from a handful half a century ago to an estimated 35,000,<br />

which includes government officials, soldiers, sailors, police<br />

and squads of national park guides in khaki shirts and<br />

pants. Most of the people live on the islands of Isabela,<br />

San Cristobal and Santa Cruz, the main base for many<br />

tourists in the Galapagos.<br />

All the commotion, Espinoza said, has been pushing the<br />

iguanas away from familiar territory. “If you have a hundred<br />

tourists passing and touching the same animal,” he said,<br />

“the animal is going to go away from that place.”<br />

Some conservations worry about the harm to the Galapagos<br />

animals from sound and light. Several inter-continental size<br />

passenger jetliners roar into the Galapagos every day and<br />

a few companies operate shuttle flights around the islands<br />

with small twin-engine propeller planes. Most of the boats<br />

that take tourists diving and on explorations on land are<br />

powered by big outboard motors. Beaches that once were<br />

dark after sunset are now often dotted with lights. The<br />

iguanas, scientists say, find the lights disorienting.<br />

“They don’t know where the beach is,” Espinoza said, so<br />

they cannot swim into the water and find food.<br />

Espinoza has requested extra staff to monitor the iguanas<br />

and says that a comprehensive, island-wide population<br />

survey is needed.<br />

Espinoza is keeping his eye on the negative trends, but he<br />

says he doesn’t think there is cause to be overly worried.<br />

“We do not have enough data to show that it is a major<br />

issue,” he said.<br />

MARINE IGUANA<br />

NEAR THREATENED

The Northern Spotted Owl is in decline across its entire<br />

range, and its rate of decline is increasing—that is the<br />

conclusion of a major demographic study produced by<br />

federal scientists, published Wednesday, December 9, 2015,<br />

in the journal “The Condor.” The study examined survey<br />

results from monitoring areas across the range of the<br />

imperiled owl.<br />

This research indicates that since monitoring began in<br />

1985, Spotted Owl populations declined 55-77 percent in<br />

Washington, 31-68 percent in Oregon, and 32-55 percent<br />

in California. In addition, population declines are now<br />

occurring in study areas in southern Oregon and northern<br />

California that were previously experiencing little to no<br />

detectable decline through 2009.<br />

“This study confirms that immediate action is needed to<br />

reduce the impact of Barred Owls and to protect all remaining<br />

Spotted Owl habitat. It also points to the need to<br />

restore additional habitat by maintaining and expanding the<br />

successful reserve network of the Northwest Forest Plan,”<br />

said Steve Holmer, senior policy advisor with American<br />

Bird Conservancy.<br />

While habitat loss continues to threaten the Spotted Owl,<br />

new threats have emerged. Barred Owls, whose range has<br />

increased in recent years to coincide with the Northern<br />

Spotted Owl, can outcompete the Spotted Owl for food and<br />

territory. The study says:<br />

We observed strong evidence that Barred Owls negatively<br />

affected Spotted Owl populations, primarily by decreasing<br />

apparent survival and increasing local territory extinction<br />

rates. … In the study areas where habitat was an important<br />

source of variation for Spotted Owl demographics, vital rates<br />

were generally positively associated with a greater amount<br />

of suitable owl habitat.<br />

However, Barred Owl densities may now be high enough<br />

across the range of the Northern Spotted Owl that, despite<br />

the continued management and conservation of suitable owl<br />

habitat on federal lands, the long-term prognosis for the<br />

persistence of Northern Spotted Owls may be in question<br />

without additional management intervention.<br />

Dr. Katie Dugger, a research biologist at the USGS Oregon<br />

Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit of Oregon<br />

State University and lead author on the report, said: “The<br />

amount of suitable habitat required by Spotted Owls for<br />

nesting and roosting is important because Spotted Owl<br />

survival, colonization of empty territories, and number of<br />

young produced tends to be higher in areas with larger<br />

amounts of suitable habitat, at least in some study areas.”<br />

Much attention has turned to the increased threat posed<br />

by Barred Owls since the Northern Spotted Owl was listed<br />

as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act<br />

in 1990. However, Holmer stressed that adequate habitat<br />

is the only long-term solution to the Barred Owl threat.<br />

“Science shows that Northern Spotted Owls and Barred<br />

Owls can coexist where there is enough high-quality habitat,”<br />

he said. “A large amount of owl habitat will become available<br />

as the Northwest Forest Plan continues to restore the<br />

old-growth ecosystem.”<br />

ORTHERN SPOTTED<br />

WL POPULATIONS<br />

IN RAPID DECLINE<br />

DEC 10,<br />

2015<br />

BY STEVE<br />

HOLMER

The Northern Spotted Owl is a rare raptor often associated<br />

with the complex features and closed canopy of mature<br />

or old-growth forests. Since it is associated with older<br />

forests, the owl serves as an “indicator species”—its presence<br />

indicates that the forest is healthy and functioning properly.<br />

Historically, Spotted Owl decline has been traced to habitat<br />

loss caused primarily by logging. Because the owl is dependent<br />

on older forest types, logging of old-growth forests is<br />

particularly harmful. Once these forests are logged, it can<br />

take many decades before suitable habitat regrows.<br />

The Northern Spotted Owl’s 1990 listing intensified issues<br />

concerning federal forest management. As a consequence of<br />

prior overcutting of owl habitat and a lack of compliance<br />

by the land-management agencies with wildlife protection<br />

requirements, logging of federal forests was largely halted<br />

across the owl’s range.<br />

In reaction to the stalemate over federal forest management,<br />

in 1994, the Clinton Administration established the Northwest<br />

Forest Plan, a landscape-level resource management<br />

plan that established a series of forest reserves across the<br />

range of the Northern Spotted Owl. The plan was intended<br />

to both protect remaining owl habitat and to encourage<br />

development of future habitat.<br />

After 20 years, USDA Forest Service monitoring reports<br />

indicate the plan is meeting its objectives to restore wildlife<br />

habitat as well as to improve water quality; forests of the<br />

Northwest are also now storing carbon instead of acting<br />

as a source of emissions.<br />

“The monitoring reports confirm that the system of reserves<br />

has slowed the decline of the owl,” Holmer said. “But the<br />

Spotted Owl’s continued decline makes clear that this<br />

reserve system is not enough due to competition from<br />

Barred Owls. Urgent action is needed to address the Barred<br />

Owl threat and to protect all Spotted Owl habitat on federal<br />

land.”<br />

Since monitoring began in 1985,<br />

the spotted owl populations declined<br />

55% - 77%<br />

in Washington<br />

31% - 68%<br />

in Oregon<br />

32% - 55%<br />

in California<br />

SPOTTED<br />

OWL<br />

SCIENTIFIC NAME:<br />

Strix occidentalis<br />

SIZE: 45” wingspan<br />

DIET: Carnivore<br />

SPOTTED OWL<br />

NEAR THREATENED<br />

FUN FACT: Spotted owls do not build their own nests, instead<br />

making use of cavities found in trees, and abandoned nests.

LBATROSS POPU-<br />

ATIONS IN DECLINE<br />

ROM FISHING AND<br />

NVIRONMENTAL<br />

HANGE<br />

BY BRITISH ANTARCTIC SURVEY<br />

NOV 20, 2017<br />

The populations of wandering, black-browed and grey-headed<br />

albatrosses have halved over the last 35 years on sub-antarctic<br />

Bird Island according to a new study published today<br />

(20 November) in the journal Proceedings of the National<br />

Academy of Sciences.<br />

The research, led by scientists at British Antarctic Study<br />

(BAS), attributes this decline to environmental change, and<br />

to deaths in longline and trawl fisheries (known as bycatch).<br />

Albatrosses are the world’s most threatened family of birds.<br />

There are 22 species; according to the IUCN Red List, 17<br />

of these are ‘Threatened with extinction’ and the remaining<br />

five are considered to be ‘Near-threatened’. BAS scientists<br />

at Bird Island have been monitoring the populations since<br />

1972.<br />

By analysing the breeding histories of more than 36,000<br />

individually ringed albatrosses, researchers have found<br />

decreases in the survival rates of both adults and juveniles,<br />

causing serious declines in population growth rates with<br />

long-lasting effects.<br />

Lead author Dr Deborah Pardo of the British Antarctic<br />

Survey, says:<br />

“Our study shows that bycatch in fisheries and environmental<br />

change both contribute to reducing the survival rates of<br />

the birds. While we know population sizes were affected by<br />

bycatch from the mid 1990s, more recent climatic changes<br />

including stronger and more poleward winds, increased sea<br />

surface temperature and reduced sea ice have worsened<br />

the impacts.<br />

We also found the grey-headed albatross population was<br />

particularly affected by the climatic event of El Niño, which<br />

coincided with increased fishing activity in their foraging<br />

areas. El Niño reduced the amount of food available so<br />

the birds probably switched to feeding on discards behind<br />

fishing vessels, increasing the number being hooked on<br />

longlines.”<br />

Co-author Professor Richard Phillips of the British Antarctic<br />

Survey, says:<br />

“This is the first comprehensive study at South Georgia<br />

and one of the few globally to examine the impacts of both<br />

climate change and fisheries on populations of long-lived<br />

seabirds. Identifying that bycatch is having a major impact<br />

on grey-headed albatrosses was unexpected, as mortalities of<br />

this species during setting of longlines are rarely recorded<br />

Albatrosses are the<br />

world’s most threatened<br />

family of birds.<br />

by observers on board fishing vessels. The results underline<br />

how important it is to improve fisheries management.<br />

Whilst BAS has worked with Commision for the Conservation<br />

of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) to<br />

introduce measures that have effectively eliminated bycatch<br />

around South Georgia, evidence from our long-term monitoring<br />

shows that more is needed elsewhere in the Southern<br />

Ocean to avoid the unnecessary deaths of tens of thousands<br />

of birds each year.”

WANDERING ALBATROSS<br />

WANDERING<br />

ALBATROSS<br />

VULNERABLE<br />

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Diomedea exulans<br />

SIZE: 10’2” Wingspan<br />

DIET: Carnivore<br />

FUN FACT: Sometimes these birds eat so much<br />

they can’t fly and just have to float on the water.

Fish

VERFISHED:<br />

BY PAIGE ROBERTS<br />

JUNE 09, 2016<br />

ELLOWFIN TUNA<br />

N THE BRINK<br />

From sandwiches to sushi, tuna is a global staple. World<br />

tuna catch is worth more than $42 billion annually, making<br />

the tuna industry a giant in the fishing world. It supports<br />

millions of jobs and provides food security for people in<br />

developed and developing countries alike. So when the<br />

conservation status of one species suddenly changes from<br />

sustainably fished to overfished, alarm bells ring across<br />

the world and, in this case, especially in the Indian Ocean.<br />

In November 2015, the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission<br />

(IOTC) listed one of the Indian Ocean’s highest value fish,<br />

yellowfin tuna, as “overfished.” This was a blow to fishing<br />

economies throughout the Indian Ocean that depend on<br />

tuna as an export. Over the entire Indian Ocean, yellowfin<br />

tuna accounts for 45% of tuna landings and is worth US<br />

$1.2 billion when sold off the boat (before processing). After<br />

moving through a value chain that often lands it on dinner<br />

plates thousands of miles from where it was caught, the<br />

total value of Indian Ocean tuna triples.<br />

In countries with small-scale tuna fisheries, the rapid decline<br />

of yellowfin populations could trigger a significant downturn<br />

in their fishing economies. For example, in Somalia, yellowfin<br />

tuna makes up 15% of artisanal catch. This one species<br />

contributed US $6.5 million to the Somali economy in 2010.<br />

If this fish were to disappear, the lost revenue would be<br />

detrimental to the livelihoods of Somali artisanal fishers.<br />

Tuna fishing has a long history dating back thousands of<br />

years. However, the Indian Ocean’s proliferation as a global<br />

seafood source began in the 1980s with the introduction<br />

of highly efficient fishing gear. Between the mid-1950s to<br />

around 1980, annual catch of yellowfin tuna in the Indian<br />

Ocean was a fairly constant 20,000 to 60,000 tons, caught<br />

mostly by Asian longlining vessels. But beginning in 1982,<br />

annual tuna catch in the Indian Ocean ballooned, reaching<br />

900,000 tons by 1999.<br />

Global expansion and technological developments had a<br />

major impact on tuna fishing. In the early 1980s, European<br />

purse seine vessels entered the scene. This highly efficient<br />

fishing method uses a large net to surround an entire<br />

school of tuna, rather than catching one fish per hook<br />

as on a longline. Purse seiners grew even more efficient<br />

with the use of fish aggregating devices (FADs). These<br />

are floating structures that attract fish, making it easier<br />

to surround them with the large net. The rapid increase<br />

in purse seine vessels, coupled with an increase in fishing<br />

effort by longliners, resulted in a dramatic increase in tuna<br />

catch to 350,000 tons per year.<br />

These fishing fleets are fulfilling a ravenous global appetite<br />

for tuna. As the demand for tuna has grown, so has the<br />

range of these vessels. After decades of overfishing in<br />

their own waters, fishers are expanding beyond their home<br />

countries’ depleted ocean resources to fish in the waters of<br />

other countries that lack the ability to manage or prevent<br />

foreign fishing. For countries that are still developing their<br />

fishing industries, foreign fishing vessels are competing with<br />

local fishers for decreasing resources. In Somali waters,<br />

foreign fishers extract three times more fish than domestic<br />

fishers do.<br />

The wakeup call by the IOTC may be forcing a change.<br />

The declaration of yellowfin as overfished has forced the<br />

tuna fishing industry to take pause. Even companies whose

FUN FACT: Yellowfin tuna are one of the few partially<br />

warm-blooded fish species.<br />

incentives are profits rather than conservation are coming<br />

to recognize that continuing to overfish yellowfin will mean<br />

losing their industry forever. In response, fishing companies<br />

and supermarkets are partnering with NGOs in a call for<br />

a 20% reduction in catch.<br />

YELLOW-<br />

FIN TUNA<br />

SCIENTIFIC NAME:<br />

Thunnus albacares<br />

SIZE: 6’- 7’ long<br />

DIET: Carnivore<br />

Their cooperation is pressuring the IOTC to create better<br />

harvest control rules for yellowfin and other heavily exploited<br />

species such as skipjack. Last month’s session of the IOTC<br />

resulted in agreement on a 20% reduction in skipjack and<br />

10% reduction in yellowfin catch across the Indian Ocean.<br />

This is an excellent first step. However, reporting catch to<br />

the IOTC is voluntary and it is estimated that one third of<br />

catch goes unreported. Without full regional compliance<br />

for reporting, the IOTC cannot accurately measure how<br />

many fish are being removed. Therefore, a decrease in the<br />

allowed catch has little meaning until every country fishing<br />

for yellowfin tuna in the Indian Ocean fully reports its catch.<br />

For developing countries that are trying to grow their<br />

fisheries sectors, stopping the overfishing of an important<br />

species like yellowfin is crucial. Their ability to grow and<br />

compete on the global market depends on the industrial<br />

fleet leaving some fish in the ocean for them to catch and<br />

sell. Regional cooperation and compliance is the only way<br />

to ensure everyone can get a piece of the tuna steak.<br />

~ 350,000 tons<br />

YELLOWFIN TUNA<br />

~ 50,000 tons<br />

~ 25,000 tons<br />

NEAR THREATENED<br />

1960<br />

1980 2000<br />

ANNUAL CATCHES OF YELLOWFIN TUNA IN THE INDIAN OCEAN

GREAT<br />

WHITE<br />

SHARK<br />

FUN FACT: The lifespan<br />

of great white sharks is<br />

estimated to be as long as 70<br />

years or more.<br />

SCIENTIFIC NAME:<br />

Carcharodon carcharias<br />

SIZE: 11’- 21’ long<br />

DIET: Carnivore<br />

for weeks and months at a time,” he said according to<br />

ScienceDaily.<br />

A new study has found a drastic decline in great white shark<br />

sightings around Seal Island in False Bay, south of Cape<br />

Town, South Africa.<br />

Researchers from the University of Miami Rosenstiel School<br />

of Marine and Atmospheric Science and the Apex Shark<br />

Expeditions have been monitoring the waters for sharks<br />

around Seal Island for 18 years. They published their<br />

research in the journal Scientific Reports on Feb. 13. Seal<br />

Island is known for its large population of Cape fur seals,<br />

which are a common prey of great white sharks. Because of<br />

this, the site is famous for sightings of great white sharks<br />

diving out of the ocean to catch their seal prey.<br />

Great white sharks are one of the largest and longest living<br />

sharks species. Adults can weigh more than 2.5 tons, grow<br />

up to 20 feet long and have a lifespan of 70 years.<br />

The study lasted for 18 years and involved over 8000 hours<br />

of observation, with researchers sighting a total number of<br />

6,333 individual white sharks and 8,076 attacks on seals in<br />

this time. While the numbers for great white shark sightings<br />

were relatively stable from the start of the study in 2000 to<br />

2015, they have significantly dropped since then. The study’s<br />

lead author is University of Miami Research Associate Professor<br />

Neil Hammerschlag. Hammerschlag is also the director<br />

of the Shark Research and Conservation Program at the<br />

University of Miami. He noted why the sudden change in<br />

great white shark populations may be occurring.<br />

“In 2017 and 2018, their numbers reached an all-time low,<br />

with great whites completely disappearing from our surveys<br />

Currently, great white sharks are classified as vulnerable<br />

by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. The<br />

reason for the great white’s disappearance from this area is<br />

still unknown. One theory is the arrival of killer whales in<br />

False Bay with a particular feeding technique. Killer whales<br />

are the only known species that hunt great whites. Another<br />

study published earlier this year documented instances of<br />

killer whales preying on sharks in False Bay and selectively<br />

feeding on their liver. Other theories include over-fishing<br />

in the region or habitat loss that drove the great white<br />

sharks away.<br />

Whatever the reason may be, the loss of the great white<br />

sharks has provided a valuable opportunity for researchers<br />

to observe the changes in the ecosystem following the loss<br />

of an important apex predator.<br />

While great white sharks have been disappearing from Seal<br />

Island, an unexpected species has taken the reigns as the<br />

region’s new apex predator. Normally seen in the kelp beds<br />

inshore near Miller’s Point 18 kilometers away, sevengill<br />

sharks were spotted for the first time at Seal island in<br />

2017. Sevengill sightings in the study have been increasing<br />

ever since, coinciding with the periods of great white<br />

sharks disappearance. Sevengill sharks are known as living<br />

fossils, due to their relatedness to similar sharks from the<br />

Jurassic period. As their name implies, sevengill sharks are<br />

unique for having seven slits for their gills instead of five.<br />

These sharks are preyed on by great whites, but like great<br />

whites, they also prey on seals. The loss of their predator<br />

and competitor gives rise to a new spot for the sevengill<br />

sharks at the top of the food chain at Seal Island.<br />

REAT WHITE SHARK<br />

OPULATIONS ARE IN<br />

DECLINE<br />

BY SAMI SANIEI<br />

FEB 28, 2019

The reason for<br />

the great white’s<br />

disappearance<br />

from this area is<br />

still unknown.<br />

VULNERABLE<br />

GREAT WHITE SHARK

LASS FROGS UNDER<br />

HREAT IN LATIN<br />

MERICA<br />

BY ADRIAN REUTER<br />

AUG 21, 2019<br />

Latin America covers only 16 percent of the globe, yet it<br />

is home to 40 percent of the world’s biodiversity. In the<br />

most bio-diverse region in the world, existing species face<br />

several threats including illegal harvest, use, and trade to<br />

meet existing national and international demand, making<br />

it a prime target for illegal wildlife trafficking.<br />

Glass frogs, or “ranas de cristal,” fall among the taxa<br />

whose international trade could significantly threaten their<br />

survival in the wild.<br />

These species must already contend with challenges such<br />

as habitat degradation and destruction (in particular as a<br />

result of the expansion of commercial agriculture across<br />

Central and South America), and the risk of chytridiomycosis<br />

— an infectious disease caused by the chytrid fungi<br />

Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis and B. salamandrivorans,<br />

that has been linked to dramatic population declines of<br />

amphibian species.<br />

In addition, the wild populations of several species have<br />

naturally restricted ranges, with the highest levels of locally<br />

occurring species found in Colombia (21 species), followed<br />

by Venezuela (16 species), and Peru (11 species).<br />

Relying exclusively on permanent bodies of running water<br />

such as streams and waterfalls — and with natural distribution<br />

restricted to the American continent ranging from<br />

Southern Mexico to Northern Argentina and across the<br />

Andes from Venezuela to Bolivia — glass frogs are categorized<br />

from Critically Endangered to Vulnerable (depending<br />

on the species) on the most recent IUCN Red List<br />

assessments.<br />

countries, suggesting that demand is high. Even though<br />

not all of the glass frog species have been recorded in<br />

international trade, similarity in color and size makes it<br />

difficult to differentiate among the various species, which<br />

poses a challenge to those responsible for the regulation<br />

and control of its trade.<br />

During this CITES CoP18, a proposal by Costa Rica, El<br />

Salvador, and Honduras aims to include these frogs in<br />

Appendix II. Specifically they propose that 17 species across<br />

the four genera be included due to their Red List conservation<br />

status.<br />

Eleven more species are proposed for Appendix II due to<br />

the real possibility that they may soon become threatened<br />

with extinction due to their documented presence in international<br />

trade. And still 77 more species are proposed for<br />

Appendix II due to their resemblance to threatened species<br />

— making it difficult for customs and enforcement officials<br />

to tell them apart.<br />

With field programs in many glass frog range state countries<br />

in Latin America, WCS works to conserve many of the<br />

habitats and ecosystems where these unique amphibians<br />

live. We share the concern of international trade becoming<br />

an additional and significant threat to many species.<br />

For this reason, WCS will continue to invest in efforts to<br />

ensure the survival and sustainability of glass frogs in the<br />

wild, and calls on all governments to support the proposal<br />

— so as to catalyze international trade regulatory actions<br />

now and avoid coming back to CoP19 three years from now<br />

to learn how much more endangered these frog species are.<br />

With the particularity of having a transparent abdominal<br />

skin through which their internal organs are visible,<br />

glass frogs have become popular in the international pet<br />

trade. These species sell for significant prices in consumer<br />

GLASS<br />

FROGS<br />

SCIENTIFIC NAME:<br />

Centrolenidae<br />

SIZE: .75” - 3” long<br />

DIET: Carnivore<br />

FUN FACT: Glass frogs are nocturnal and spend their<br />

days hidden under leaves and among branches.

WHAT’S HURTING<br />

GLASS FROGS?<br />

Illegal Wildlife<br />

Trafficking & Trading<br />

Commercial<br />

Agriculture<br />

Infectious Disease<br />

GLASS FROGS<br />

MULTIPLE GROUPS

ALIFORNIA TIGER<br />

ALAMANDER<br />

BY SACRAMENTO FISH & WILDLIFE<br />

OFFICE DEC 6, 2017<br />

PECIES INFORMATION<br />

California tiger salamanders in the Central Valley are threatened.<br />

The species is likely to become endangered in the<br />

foreseeable future throughout all or a significant portion of<br />

its range, but they are not in danger of extinction right now.<br />

The California tiger salamander (Ambystoma californiense)<br />

is an amphibian in the family Ambystomatidae. This is a<br />

large, stocky salamander, with a broad, rounded snout.<br />

Its small eyes, with black irises, protrude from its head.<br />

Adult males are about 20 cm (about 8 in) long. Females are<br />

about 17 cm (about 7 in). “Tiger” comes from the white or<br />

yellow bars on California tiger salamanders. The background<br />

color is black. The belly varies from almost uniform white<br />

or pale yellow to a variegated pattern of white or pale<br />

yellow and black.<br />

Males can be distinguished from females, especially during<br />

the breeding season, by their swollen cloacae, a common<br />

chamber into which the intestinal, urinary, and reproductive<br />

canals discharge. They also have more developed tail fins.<br />

Adults mostly eat insects. Larvae eat things like algae,<br />

mosquito larvae, tadpoles and insects.<br />

The species is restricted to grasslands and low foothills<br />

with pools or ponds that are necessary for breeding. Natural<br />

breeding areas, mostly vernal pools (a seasonal body of<br />

standing water), are being destroyed. Ranch stock ponds<br />

that are allowed to go dry help take the place of vernal<br />

pools for breeding. A California tiger salamander spends<br />

most of its life on land. Actually, “in the land” - it lives<br />

underground, using burrows made by squirrels and other<br />

burrowing mammals. Catching a California tiger salamander<br />

requires a permit, but you may be able to see larvae<br />

swimming around.<br />

and Sonoma. This species is restricted to California and<br />

does not overlap with any other species of tiger salamander.<br />

They are restricted to vernal pools and seasonal ponds.<br />

Birds such as herons and egrets, fish, and bullfrogs prey<br />

on California tiger salamanders.<br />

The primary cause of the decline of California tiger salamander<br />

populations is the loss and fragmentation of habitat<br />

from urban development and farming. This includes the<br />

encroachment of nonnative predators such as bullfrogs,<br />

which kill larvae and nonnative salamanders that have<br />

been imported for use as fish bait and may out-compete<br />

the California tiger salamanders.<br />

Reduction of ground squirrel populations to low levels<br />

through widespread rodent control programs may reduce<br />

availability of burrows and adversely affect the California<br />

tiger salamander. In addition, poison typically used on<br />

ground squirrels is likely to have an adverse effect on<br />

California tiger salamanders, which are smaller than the<br />

target species and have permeable skins.<br />

A deformity-causing infection, possibly caused by a parasite<br />

in the presence of other factors, has affected pond-breeding<br />

amphibians at known California tiger salamander breeding<br />

sites. Use of pesticides, such as methoprene, in mosquito<br />

abatement may have an indirect adverse effect on the<br />

California tiger salamander by reducing the availability<br />

of prey.<br />

Automobiles and off-road vehicles kill a significant number<br />

of migrating California tiger salamanders, and contaminated<br />

runoff from roads, highways and agriculture may adversely<br />

affect them.<br />

The California tiger salamander is found mostly the Central<br />

Valley of California. Small populations around Santa Barbara

CALIFORNIA TIGER<br />

SALMANDER<br />

SCIENTIFIC NAME:<br />

Ambystoma californiense<br />

SIZE: 7”- 8” long<br />

DIET: Carnivore<br />

FUN FACT: Tiger salamanders<br />

are one of the largest terrestrial<br />

salamanders in the U.S.<br />

The primary cause of the decline<br />

of California tiger salamander<br />

populations is the loss and fragmentation<br />

of habitat from urban<br />

development and farming.<br />

CALIFORNIA TIGER SALAMANDER<br />

VULNERABLE

E

ND NOTES<br />

We live in an age of rapid and unprecedented planetary<br />

change. Indeed, many scientists believe our ever-increasing<br />

consumption, and the resulting increased demand for<br />

energy, land and water, is driving a new geological epoch:<br />

the Anthropocene. It’s the first time in the Earth’s history<br />

that a single species – Homo sapiens – has had such a<br />

powerful impact on the planet.<br />

This rapid planetary change, referred to as the ‘Great<br />

Acceleration’, has brought many benefits to human society.<br />

Yet we now also understand that there are multiple connections<br />

between the overall rise in our health, wealth, food<br />

and security, the unequal distribution of these benefits and<br />

the declining state of the Earth’s natural systems. Nature,<br />

underpinned by biodiversity, provides a wealth of services,<br />

which form the building blocks of modern society; but both<br />

nature and biodiversity are disappearing at an alarming<br />

rate. Despite well-meaning attempts to stop this loss through<br />

global agreements such as the Convention on Biological<br />

Diversity, we are failing; current targets and consequent<br />

actions amount, at best, to a managed decline. To achieve<br />

climate and sustainable development commitments, reversing<br />

the loss of nature and biodiversity is critical.

B

IBLIOGRAPHY<br />

https://www.pbs.org/wnet/need-to-know/five-things/the-great-american-bison/8950/<br />

https://www.livescience.com/27519-pacific-leatherback-turtle-decline.html<br />

https://phys.org/news/2017-11-albatross-populations-decline-fishing-environmental.html<br />

https://securefisheries.org/blog/overfished<br />

https://medium.com/@WCS/glass-frogs-under-threat-in-latin-america-bc50896d4af2<br />

https://www.earthday.org/2018/05/18/populations-of-living-things-across-all-speciesare-declining-and-this-is-very-worrisome/<br />

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2016/12/cheetahs-extinction-endangered-africa-iucn-animals-science/<br />

http://www.themiamiplanet.org/2015/06/15/galapagos-marine-iguanas-strugglingagainst-tourists-black-rats-and-the-weather/<br />

https://abcbirds.org/article/northern-spotted-owl-populations-in-rapid-decline-new-studyreports/<br />

https://www.jhunewsletter.com/article/2019/02/great-white-shark-populations-are-indecline<br />

https://www.fws.gov/sacramento/es_species/Accounts/Amphibians-Reptiles/ca_tiger_salamander/<br />

https://s3.amazonaws.com/wwfassets/downloads/lpr2018_summary_report_spreads.<br />

This book is set in multiple contrasting typefaces. All headers<br />

and titles are Poleno Extrabold and Semibold, Futura<br />

Medium Condensed is used for subheaders, and Century<br />

Schoolbook Pro Regular and Italic are used for body copy.