combinepdf (56)

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

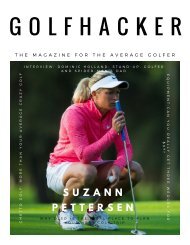

I S S U E N O . 2

V O L U M E N O . 1

INSIDE

HISTORY

C R I M E A N D T H E U N D E R W O R L D

THE

TRIALS

OF

LIZZIE

BORDEN

* Stand and deliver: Dick Turpin * the real peaky blinders * h.h Holmes * ANgels in The House*

*Bootlegging and prohibition * Al Capone * burke and hare * The evolution of the Crime investigation *

*Peine Forte Et DURe * The Morellos * How to get away with murder in the middle ages *

PEN & SWORD BOOKS

TRUE CRIME 25%

DISCOUNT

RRP: £19.99

NOW: £14.99

ISBN: 9781526755186

RRP: £12.99

NOW: £9.74

ISBN: 9781781592885

RRP: £12.99

NOW: £9.74

ISBN: 9781526764409

RRP: £19.99

NOW: £14.99

ISBN: 9781526747433

RRP: £14.99

NOW: £11.24

ISBN: 9781526742025

RRP: £19.99

NOW: £14.99

ISBN: 9781526748768

RRP: £14.99

NOW: £11.24

ISBN: 9781526751621

RRP: £14.99

NOW: £11.24

ISBN: 9781526763389

TO ORDER CALL AND QUOTE CODE HISTORY25 TO RECEIVE YOUR 25% DISCOUNT:

01226 734222

OR ORDER ONLINE

www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LTD

Avampato

Christa

Stephen Carver

Dr

Nell Darby

Dr

Rebecca Frost

Dr

James

Mallory

Kevern

Nick

Ruggiero

Anthony

O'Shaughnessy

Patrick

Smith

Conal

Walsh

Robert

Elliott Watson

Dr

John Woolf

Dr

is no escaping the fact that crime has always been

There

part of history. Wherever there is an opportunity then

a

are always those who aim to benefit from it. For

there

issue of INSIDE HISTORY, we have aimed to enter

this

Rebecca Frost investigates the evolution of the myth

Dr

the notorious H.H Holmes. How many did he

behind

kill and how much of what he did (or even, did

actually

do) was the work of his own imagination? Was he

not

for helping to create his own sensationalism

responsible

stories written about him?

the

media, since the early days of the printing press, has

The

been keen to report on murders. Lizzie Borden's

always

was no different. Yet, her particular case raises a

case

of issues. Despite being found innocent of the

number

of her father and stepmother, Borden faced

murders

trials following her acquittal. From her own

many

to media frenzy and of course, the

community,

of history.

perception

criminals have never needed the media to help

Some

to become part of the public imagination. Over

them

they can become glamorous based on the work of

time

writers eager to tell a story. Dick Turpin is one

fictional

case. The image of Turpin is often portrayed as the

such

highwayman, feared by the wealthy and

gentleman

by women. The real Turpin is a completely

adored

story as Dr Stephen Carver will reveal.

different

has unfortunately become a form of

Crime

with many television channels dedicated

entertainment

time to documentaries and movies about famous

air

There is of course an issue with this. How

criminals.

do we really know about these people? How can

much

the fact from the fiction? As historians our job is not

tell

the deeds of these individuals but to pursue

glamourise

truth with the evidence at hand. I only hope that we

the

us as we take you from the Middle Ages right up to

Join

20th Century on this journey of historical crime and

the

Underworld. As Nick Ross from Crimewatch used to

the

"Don't have nightmares...sleep well."

say:

A NOTE

BY THE

EDITOR

"DON'T HAVE NIGHTMARES...

SLEEP WELL"

Nick Ross. BBC Crimewatch Presenter

the criminal underworld throughout time.

E D I T O R

Nick Kevern

C O N T R I B U T O R S

have managed to do just that.

@inside__history insidehistorymag @InsideHistoryMag

to get away with murder in the

How

Ages

Middle

Turpin: The Not-So Dandy

Dick

Highwayman

man: The Evolution of the mth

Self-made

H.H Holmes

of

the St Valentine's Day Massacre

How

the Jazz Age

killed

changing world of Crime

The

Investigations

10

18

22

30

36

40

I N S I D E H I S T O R Y

07

30

I S S U E 0 2 / C R I M E A N D T H E U N D E R W O R L D

C O N T E N T S

07

12

26

48

48

53

26

22

Crushing the Confession

Burke and Hare: Dealers in Death

Angels in the House

The trials of Lizzie Borden

The Morellos: Families at War

The REAL Peaky Blinders

12

18

Prohibition in New York City

44

40

Discover Europe's Oldest Surviving

Surgical Theatre dating to 1822

Open:

Mondays

2:00 PM - 5:00 PM

Tuesdays to Fridays & BH Mondays

10:30 AM - 5:00 PM

Saturdays & Sundays

12:00 PM - 4:00 PM

Weekend Talks* 11:00 AM & 4:00 PM

*Advance Booking Recommended

Admission Charged

9A St Thomas St

London, Southwark, SE1 9RY

www.oldoperatingtheatre.com

HOW TO GET AWAY

WITH MURDER IN

THE MIDDLE AGES

WORDS BY CONAL SMITH

Watch any film or TV series set in the middle ages, or

a middle ages-esque environment such as Westeros,

and you are likely to come across barbarism. Heads

are chopped off and men are hanged for anything,

including the smallest of crimes. While there may be

some exaggeration, go back to the middle ages and

almost all serious crime was certainly punished in this

way. Murder, serious theft and burglary of goods over

12 pence(!) were capital offences for anyone over the

age of 10. Here, however, are a few ways that a crafty

criminal could try to avoid the noose.

Although in some cases it was possible to claim

sanctuary indefinitely, it was more common that a

criminal would need to make a choice within 40 days.

Either they must opt to go into permanent exile,

receiving safe passage as they left the country, or

they had to present themselves to a court. Presenting

one’s self to a court meant facing the full force of the

King’s justice, and so the option of fleeing England to

start a new life overseas could be a route to avoiding

this.

Plead benefit of the Clergy

If you were a member of the clergy (priest, monk or

nun), you escaped the King’s justice automatically.

Instead of being tried in the King’s courts, you would

be tried by your fellow churchmen in a Church court.

Here punishments tended to focus more on penance

than punishment. Though standing in the village

square in nothing but your small clothes sounds far

from pleasant, it certainly sounds preferable to

hanging. Surely this was only open to real members

of the clergy though?

Wrong. ANYONE could claim benefit of the clergy.

The ‘proof’ if one can call it that was merely the ability

to read a passage in latin. Still think that sounds

tough as you had to learn Latin? Wrong again. There

was a set passage, which became known as the ‘neck

verse’ that was used to test this. Hence, even if you

could not speak latin, you could learn psalm 51 by

heart and then simply recount it when the bible was

placed in front of you to test whether you were

indeed clergy. While you might not completely get

away with murder, being liable for a Church

punishment, a simple bit of preparation was a

surefire way to avoid execution for murder. This route

even went on far beyond the middle ages, not being

finally abolished until 1823!

Sanctuary

Even if you had not put in the requisite preparation

to plead benefit of the clergy, the Church still

provided a clear route to avoiding the death penalty.

There was a legal ability to claim sanctuary in a holy

place, until its abolition in 1624. If a criminal was able

to reach a Church or Cathedral, their pursuers were

not able to enter a holy place and arrest them,

something which could be seen a desecrating a holy

site.

8 / CRIME AND THE UNDERWORLD

There was a legal

ability to claim

sanctuary in a holy

place, until its

abolition in 1624.

Victory taken

as clear proof

of innocence

Trial by Combat

A far riskier route, but one which could see you

serving no punishment whatsoever, was dependent

on presenting yourself to the authorities. Once

arrested, if there was some element of doubt over

your guilt you could request trial by combat rather

than the more common trial by jury. This system was

in place from the Norman Conquest and meant that,

so long as your accuser was not someone deemed

unable to fight (through age, sex or disablity), you

could challenge them to single combat. In a 60 foot

square arena, the two of you would engage in a fight,

either to the death or until one of the participants

yielded, with a victory taken as clear proof of

innocence; for the authorities this also had the

benefit of sometimes avoiding the need to employ a

hangman!

The three possibilities hitherto described are some of

the purely medieval routes of escape available to you,

but there were also some routes that continue to be

employed far beyond the period and even in some

cases up to this day.

In the first instance of course there is the simple

route of fleeing as far and as fast as possible. While

there were medieval methods to catch a fugitive,

such as the hue and cry, the reach of these attempts

were geographically very restricted. Secondly, one

could admit guilt, but then try and obtain a royal

pardon. For those who could afford it this could

sometimes be bought. However, more common in

the Later Middle Ages are the many violent criminals,

including murderers, who received a royal pardon in

return for military service overseas. If a guarantee of

hardship and risk of violent death did not appeal, the

modern mafia staple of witness intimidation would

also have been available to you dependent on wealth

and influence, particularly given the lack of forensic

evidence to ensure a conviction without sworn

testimony.

So there you have it, if you committed a murder in

the middle ages there may have been no way of

guaranteeing escaping the long arm of the law.

However, there were plenty of options to choose

from in an attempt to avoid swinging for your crimes.

Conal Smith is part of the

editorial team at the

VersusHistory Podcast

WORDS BY NICK KEVERN

CRIME AND THE UNDERWORLD / 9

CRUSHING THE

CONFESSION

WORDS BY PATRICK O'SHAUGHNESSY

IMAGE: WIKIMEDIA

O'Shaughnessy is the Head of History at a

Patrick

international school in the Middle East.

prestigious

is a Co-Editor of the Versus History Podcast and

He

writes on various subjects related to History.

regularly

is currently writing a book which focuses on

Patrick

causes and events of the American Revolution.

the

If your English ancestors stood trial for a crime in a

court of law before 1772, the sentence - if convicted -

could be extremely severe. For instance, when the

Gunpowder Plotters were convicted of ‘high treason’

against King James I in January 1606, they were

publically hung, drawn and quartered before of a

hostile and highly unsympathetic crowd in London.

The potential punishments for those convicted of a

crime during both the Tudor and Stuart eras (1485-

1714) could include - but were not limited to - being

beheaded, death by hanging and being put in the

stocks, depending on the severity of the crime that

one was found guilty of committing. Capital

punishment was constant during this time of great

political, social and cultural flux. Following the demise

of the Stuart dynasty in 1714, the punishment dished

out to offenders during the reigns of the first three

Georgian monarchs who reigned between 1714-1820,

could still involve the death penalty. By 1800, the

application of the death penalty was extended to

cover over 200 different crimes, including theft.

Transportation of convicted felons was also used until

1867, during the reign of Queen Victoria. As Historian

E.P Thompson argued, ‘The commercial expansion,

the enclosure movement, the early years of the

Industrial Revolution - all took place within the

shadow of the gallows.’ It is clear, therefore, that the

huge societal shifts which were taking place in

Britain during the 18th and 19th centuries did not

axiomatically lead to changes or reform in the

criminal justice system.

The application of capital punishment and the

banishment of convicted criminals to distant colonial

outposts is generally well known and documented.

However, a lesser-known, but perhaps equally

barbaric feature of the criminal justice system until

1772 was an inherent part of the prosecution stage,

rather than the punishment decreed as part of the

sentence. If prosecuted in a court of law for a capital

offence (e.g: murder or treason) during the reign of

King George III (1760-1820) or a monarch preceding

him, your English ancestors would have been faced

with a simple choice. To plead ‘guilty’ or ‘innocent’ of

the stated crime in a court of law. Right? Actually, it’s

wrong!

The choice of plea facing the accused at the start of a

trial was not a simple binary between ‘innocent’ on

the one hand and ‘guilty’ on the other. There was a

THIRD option. This is where things get slightly

complex but very interesting. We can safely assume

that a plea of ‘guilty’ in a trial for a capital offence

would have meant almost certain conviction, death

and the subsequent forfeiture of all land and property

owed to the Crown. A plea of ‘innocent’ would have

either resulted in the previous outcome or if one was

lucky, an acquittal (although this was unlikely in

treason cases as these were often a fait accompli).

The third option would have appealed to those with

significant estates and wealth. To avoid the seizure of

all property and estates by the Crown, the accused

could refuse to enter a plea at the start of the trial

when requested to do so. This could result in what

was known as ‘peine forte et dure’. In English, this

meant ‘hard and forceful punishment’. When this

eventuality occurred, the courtroom proceedings

were suspended, as a plea was necessary to proceed.

The defendant was subsequently subjected to a

process of crushing by increasingly heavier rocks,

hence the ‘hard and forceful punishment’ element.

The process was designed to elicit a plea - either

‘guilty’ or ‘innocent’ from the defendant - which

would then result in the process of crushing being

terminated and the courtroom trial being resumed.

However, the process of ‘peine forte et dure’ did not

often result in a plea being entered, as one may think,

despite the obvious excruciating and slow death that

would result. The reason for this is to do with the

forfeiture of wealth, assets and titles to the Crown

that a ‘guilty’ verdict in a court of law would entail.

Indeed, if the accused were to perish during the

‘crushing’ process, they would technically die as an

‘innocent’ person. Therefore, the ‘next of kin’ could

inherit the wealth of the deceased, rather than it

being seized for the Crown.

During the infamous Salem Witch Trials of 1692 in the

British Colony of Massachusetts, an elderly individual

named Giles Corey, who was born in Northampton in

1611 and emigrated to the American colonies in his

younger years, refused to enter a plea to the court in

his trial for alleged witchcraft. Corey was subjected to

the brutal process of peine forte et dure and was

subsequently crushed to death. Legend has it that

Corey endured the entire crushing process in silence.

Whether or not this is true, Corey died an innocent

man in the eyes of the court and could, therefore,

bequeath an inheritance to his immediate family. The

awful spectre of this elderly colonist being crushed to

death may well have been one of the causal factors

behind the eventual conclusion of the Witch Trials in

Salem, along with the growing accusations of

witchcraft aimed at women at the apex of the social

hierarchy. Whatever the truth, the history of peine

forte et dure demands attention as a more brutal part

of Britain’s legal and judicial history.

CRIME AND THE UNDERWORLD / 11

DICK TURPIN:

THE NOT SO

DANDY

WORDS BY DR STEPHEN CARVER

HIGHWAYMAN

In popular history, the name ‘Dick Turpin’ evokes a

character at once handsome, brave and funny, his cry

of ‘Stand and deliver!’ once causing many a lady

traveller’s heart to flutter. Not as famous as he was in

the seventies, perhaps, when he had his own TV

show, but he remains a real Jack Sparrow, with a set

of adventures ingrained in the national psyche, most

notably his famous ride from London to York in a

night on the equally legendary Black Bess. Like a

Georgian Jesse James, the ‘gentleman highwayman’

is the outlaw king and a symbol of rebellious

Englishness. The reality was, of course, much less

glamorous.

The best original biographical source is a chapbook

entitled The Genuine HISTORY of the LIFE of

RICHARD TURPIN, The noted Highwayman, Who was

Executed at York for Horse-stealing, under the Name

of John Palmer, on Saturday April, 7, 1739 as told by

Richard Bayes and recorded by one J. Cole in

conversation at the Green Man in Epping Forest. Not

that such ‘histories’ are exactly accurate, but this one

was at least based on contemporary witness

testimony and an account of the trial is also

appended.

According to Bayes and Cole, Turpin was born in

Hempstead in 1705. He was taught to read and write

by a tutor called James Smith, then apprenticed to a

butcher in Whitechapel. There he married a local girl

called Elizabeth Palmer, or Millington, depending on

which chapbook you believe. The couple set up in

business in Sutton, but the meat trade was no longer

guilded and unregulated competition was fierce.

Turpin took to stealing livestock until he was spotted,

and a warrant drawn up. Evading capture, he next

briefly tried his hand at smuggling before falling in

with a band of deer poachers known as ‘Gregory’s

Gang’ after its leaders, the brothers Samuel, Jeremiah

and Jaspar Gregory. The gang soon diversified into

housebreaking around Essex, Middlesex Surrey and

Kent, stealing horses, sexually assaulting

maidservants and demanding valuables with

menaces. As a contemporary newspaper reported:

"On Saturday night last, about seven o’clock, five

rogues entered the house of the Widow Shelley at

Loughton in Essex, having pistols &c. and threatened

to murder the old lady, if she would not tell them

where her money lay, which she obstinately refusing

for some time, they threatened to lay her across the

fire, if she did not instantly tell them, which she would

not do."

Beatings, rapes, scaldings and severe burns were

favourite forms of persuasion, until, pursued by

dragoons with a £100 reward on each of their heads,

several of the gang was cornered at a pub in

Westminster. The youngest, a teenager called John

Wheeler, turned King’s evidence and his compatriots

were hanged in chains. Descriptions of the remaining

outlaws were quickly circulated, including: ‘Richard

Turpin, a Butcher by Trade, is a tall fresh colour’d Man,

very much mark’d with the Small Pox, about 26 Years

of Age, about Five Feet Nine Inches high, lived some

Time ago at White-chappel and did lately Lodge

somewhere about Millbank, Westminster, wears a

Blew Grey Coat and a natural Wig’.

"Beatings, rapes, scaldings

and severe burns were

favourite forms of

persuasion, until, pursued

by dragoons with a £100

reward on each of their

heads, several of the gang

was cornered at a pub in

Westminister"

On the run, Turpin held up a well-dressed gentleman

who turned out to be the highwayman, Tom King.

They rode together for three years, living in a cave in

Epping Forest until their hideout was discovered by a

bounty-hunting servant who Turpin murdered. On

the run again, Turpin stole a horse near the Green

Man, at which point Richard Bayes became directly

involved in his own story, tracking Turpin and King to

the Red Lyon in Whitechapel. Turpin took a shot at

Bayes, hitting King instead and escaping in the

confusion. King lived for another week, during which

he cursed Turpin for a coward and gave up all their

secrets. Bayes found the cave, but Turpin was long

gone.

Becoming ‘John Palmer’, Turpin relocated to

Yorkshire as a ‘horse trader’, although he was really

stealing them from neighbouring counties.

CRIME AND THE UNDERWORLD/ 13

The closest we get to ‘Black Bess’ is a black mare

owned by a man called Thomas Creasy that Turpin

stole in York during this period. Returning home

drunk from a shooting party one day, Turpin shot a

cockerel belonging to his landlord for a lark. His

neighbour, a Mr. Hall, witnessed the event and

declared, ‘You have done wrong, Mr Palmer in

shooting your landlord’s cock’, to which Turpin

replied that if he stood still while he reloaded, he

would put a bullet in him too. Hall told their landlord

and Turpin was arrested. Being new to the area,

Turpin could not provide any character witnesses,

and although he claimed to be a butcher from Long

Sutton, something about his vague backstory did not

ring true with the examining magistrate. He was

detained while more enquiries were made in

Lincolnshire, revealing that ‘John Palmer’ was a

suspected horse thief. He was transferred to a cell at

York Castle while further investigations were

conducted.

his corpse being borne through the streets like a

martyred saint, before it was buried in lime to render

it useless for surgical dissection. He supposedly lies in

the graveyard of St George’s Church, Fishergate,

although the headstone that now graces the spot

was not there when an aspiring young novelist from

Manchester called William Harrison Ainsworth looked

for it in 1833.

By then, Dick Turpin had been largely forgotten. As

the eighteenth century progressed, turnpikes,

traceable banknotes, and expanding cities had

encroached into the traditional hunting grounds of

highwaymen and in 1805 Richard Ford’s newly

founded Bow Street Horse Patrol finally wiped them

out. For Ainsworth’s generation, highwaymen

belonged to a vanished world, and were therefore

ripe for romantic resurrection.

The highwayman Dick Turpin, on horseback, sees a phantom riding next to him. Lithograph by

W. Clerk, ca. 1839. Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC BY

Because Georgian prisoners had to pay for board and

lodgings, Turpin wrote to his brother-in-law in Essex

asking for money, but when the letter arrived

postage was owed which the recipient refused the

pay. It was returned to the post office at Saffron

Walden, where Turpin’s former tutor was now the

postmaster. Smith recognised the handwriting and

informed the authorities. Turpin was indicted for

stealing the black mare, and then identified in court

by his old teacher.

Turpin was hanged at Micklegate Bar in York on

Saturday, April 7, 1739. He was thirty-three years old.

Contemporary accounts agree that he died bravely

and with style, having bought a new frock coat and

shoes for the occasion. As Georgian hangings had a

short drop, he took about five minutes to strangle

under his own body weight. Bayes and Cole describe

Turpin was hanged at

Micklegate Bar in

York on Saturday,

April 7, 1739.

14 / CRIME AND THE UNDERWORLD

Richard Turpin shooting a man near his cave in Epping Forrest. Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC BY

Ainsworth is the real reason we have the version of

Dick Turpin we do in popular history. Turpin was the

hero of his boyhood, and he and his brother grew up

listening to their father, a prominent lawyer, spin

fireside yarns of ‘Dauntless Dick’ which the boys

would then embellish and enact in the family’s

overgrown back garden. He therefore wrote the

highwayman into his breakthrough novel Rookwood

in 1834. This tidy little gothic romance was an

overnight sensation, making its author a literary

celebrity and inspiring a national craze for Georgian

outlaws. As far as Ainsworth’s massive audience was

concerned, Turpin was the hero of Rookwood, to the

extent that the section entitled ‘The Ride to York’ was

often published separately, cementing the entirely

fictional event to the original’s biography. Ainsworth

based the episode on another apocryphal story in

which Turpin supposedly rode so quickly from a

robbery at Dunham Massey to Hough Green that he

was able to establish an alibi. The original ‘Ride to

Jack Sheppard in Bentley’s Miscellany, which ran

concurrently with Dickens’ Oliver Twist. The original

Jack Sheppard was another unremarkable Georgian

thief who achieved some notoriety in his own day by

escaping from Newgate. Jack Sheppard was another

bestseller but this time the critics turned on

Ainsworth, triggering a moral panic about the

supposedly pernicious effects of ‘Newgate novels’ on

young working-class males. When the valet François

Courvoisier murdered his master, Lord William

Russell, allegedly after reading Jack Sheppard, the

charge against Ainsworth seemed incontrovertible

and his status as a good Victorian and a serious

literary novelist never recovered. This is why we know

a lot more about Dick Turpin than we do him.

But that, as they say,

is another story…

The highwayman Dick Turpin, on horseback, arrives at a tree from which two bodies have been

hanged. Lithograph by W. Clerk, ca. 1839.. Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC BY

York’ comes from a legend about the seventeenthcentury

highwayman John Nevison, or ‘Swift Nick’,

which goes back to an account by Daniel Defoe in A

tour thro’ the whole island of Great Britain written in

1727.

Dr Stephen Carver is the

Author of THE AUTHOR WHO

The sincerest form of flattery followed, as Turpin was

rehabilitated as a national treasure, inspiring a run of

highwayman plays, novels and penny dreadfuls that

flourished well into the 1860s. After being a footnote

in eighteenth century history, Turpin’s fame was

assured by his nineteenth century fictional

doppelgänger. Almost everything we think we know

about Dick Turpin in national myth comes from the

pages of Ainsworth’s book.

AND WORK OF W.H.

LIFE

published by

AINSWORTH

& Sword books.

Pen

£25.00

RRP:

@drstephencarver

OUTSOLD DICKENS: THE

After an unsuccessful follow-up novel, Ainsworth

returned to the Newgate Calendars in 1839, serialising

16 / CRIME AND THE UNDERWORLD

FULL PAGE AD.indd 1 19/08/2019 11:40

BURKE

DEALERS IN

DEATH

WORDS

BY

ROBERT WALSH

HARE

The crimes of William Burke and William Hare are

part of Scotland’s history, living on in popular culture

even today. The subject of films, books and

documentaries, their legacy has long outlived them

and their victims. They also inspired works by Robert

Louis Stevenson and Dylan Thomas. A feature film,

not the first, was made as recently as 2010. Even Sir

Walter Scott (author of Ivanhoe) had an opinion:

“A wretch who is not worth a farthing when alive,

becomes a valuable article when knock’d on the head

and carried to an anatomist.”

In Edinburgh’s West Port district they murdered

sixteen people between November 1828 and

November 1829, selling their corpses to distinguished

surgeon and anatomist Robert Knox. Knox’s full

culpability will always be debated, Burke and Hare’s is

undoubted.

Surgeons always needed cadavers. Bodies of

executed convicts, their principal source, were simply

too few even when dissection formed part of the

death sentence and executions were common. Burke

and Hare briefly solved that problem. Body-snatchers,

grave-robbers and ‘resurrection men’ (resurgam

homo to be exact) found a solution not on the

ground, but under it. Burke and Hare, however, went

even further. In 1995 book Murdering to Dissect:

Grave-robbing, Frankenstein and the Anatomy

Literature, historian David Marshall remarks:

“Burke and Hare took grave-robbing to its logical

conclusion: instead of digging up the dead, they

accepted lucrative incentives to destroy the living.”

Edinburgh Medical School was and remains a highlyrespected

institution, but it had its dark side. Knox

was only one of several surgeons who bought

cadavers without asking where they came from.

Often lacking any other source, Knox and his

colleagues had little choice.

Edinburgh folk of the time were often staunchly

religious and, if not religious, certainly superstitious.

Their belief that a person’s body should remain

interred until the Resurrection made them hate and

fear body-snatchers. The body-snatchers in turn had

a lucrative racket where Edinburgh’s highest society

did brisk business with its lowest.

The fresher the cadaver, the more men like Knox

were prepared to pay and in cash. More could be

learned from fresh cadavers than decomposing ones.

In a society where life was often cheap, death could

be lucrative. A fresh body could fetch twenty guineas.

Families of hanged felons often claimed the body for

burial and sold it to surgeons instead.

The result was an epidemic of grave-robbing. Several

graveyards built watch-towers and employed guards.

Some families, knowing body-snatchers preferred

fresh bodies, rented huge stones. Placed over a new

grave, they prevented it being plundered. Others

used ‘mortsafes,’ iron cages rendering coffins

impregnable.

" The fresher the cadaver,

the more men like Knox

were prepared to pay and

in cash."

Based in a dingy boarding house in Tanner’s Close,

the pair’s first sale wasn’t their first murder. Lodger

‘Old Donald’ had died owing four pounds in rent, a

considerable sum for the time. A late-night visit to

Surgeon’s Square netted seven pounds and ten

shillings, around one thousand pounds today. It was

their first of many encounters with Knox.

‘Old Donald’ had proved worth more dead than alive

but, like their customers, Burke and Hare had a

supply problem. Natural death wasn’t reliable but

serial murder was, especially of people who were

readily missed. With poverty endemic in 1820’s

Edinburgh there were plenty of vagrants, tramps,

drifters and prostitutes. Having already sold the

naturally-deceased their stock-in-trade was entirely

unnatural thereafter.

Victims were lured to Tanner’s Close, plied liberally

with alcohol and suddenly ‘burked.’ ‘Burking,’ a term

used today, smothered the victim’s nose and mouth

until they suffocated. Working together, one

restrained the victim while the other suffocated

them. The victims died quickly with no visible signs of

violence to arouse suspicion, not that their customers

were especially fussy. It also provided fresh,

undamaged cadavers sold at higher prices.

CRIME AND THE UNDERWORLD / 19

Knowing they could hang for their first murder ( a

miller named Joseph in January 1829) Burke and Hare

had no qualms about fifteen more, selling their

victims to Knox at considerable profit. Their wives also

participated, helping lure victims to Tanner’s Close.

One after another their victims vanished. The more

they killed the more brazen they became, even

murdering a respectable, middle-class victim and

one of McDougal’s relatives. Their last victim was

Margaret Docherty on October 28 1829. The

interference of fellow lodgers Ann and James Gray

ended their killing spree.

The Grays became suspicious when Burke wouldn’t

allow anyone into his room. Sneaking in while Burke

was distracted they discovered Docherty’s body,

informing police even after McDougal offered them

£10 a month as a bribe. By the time police arrived

Docherty had already been sold, but Burke and his

wife told conflicting stories. Both were detained and

Hanged on 28 January 1830 Burke’s skeleton remains

on display at, ironically, Edinburgh Medical School.

Perhaps as many as 40,000 people attended his

execution with soldiers on hand to prevent disorder.

Hare and his wife vanished into obscurity as did

Burke’s widow. The disgraced Knox left Edinburgh,

dying in London in 1862.

Shortly after Burke’s dissection, MP Henry

Warburton’s Anatomy Bill failed to get through

Parliament. In 1832 his second attempt succeeded

after John Bishop and Thomas Williams were hanged

for a similar crime. Warburton’s 1832 Anatomy Act

granted anatomists unclaimed bodies from

workhouses and hospitals, also ending dissection of

executed convicts. Bishop and Williams had attracted

similar notoriety and a grim nickname; The London

Burkers.

William Burke murdering Margery Campbell - the last of the Burke and Hare murders

Credit: WikiMedia

Docherty’s body was discovered at Knox’s dissecting

room the next day. She was identified by the Grays as

the missing woman. Hare and his wife were also

arrested.

The trial was a public sensation and Burke might

have won had Hare not turned King’s Evidence to

cheat the hangman. In return, Hare was released.

Tried on Christmas Eve, 1829 and convicted on

Christmas Day, Burke was condemned to hang.

Passing sentence, Lord Justice-Clerk David Boyle

added an ironic stipulation:

Walsh is the

Robert

of MURDERS,

Author

AND

MYSTERIES

IN NEW

MISDEMEANORS

published by America

YORK

Time

Through

£18.99

RRP:

“Your body should be publicly dissected and

anatomised. And I trust, that if it is ever customary

to preserve skeletons, yours will be preserved, in

order that posterity may keep in remembrance your

atrocious crimes.”

@ScribeCrime

20 / CRIME AND THE UNDERWORLD

The execution of William Burke . Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC BY

ANGELS IN THE

HOUSE:THE NOT SO

ANGELIC VICTORIAN

HOUSEWIVES

WORDS BY

DR JOHN WOOLF

Angels in the House: subservient and submissive,

demure and deferential. The ideal Victorian woman

lived safely ensconced in the heavenly homestead: a

refuge from the rambunctious world outside. Snug in

domesticity she cared for home, husband and child.

She was morally superior, passive and ‘passionless’;

her beauty reflected in ‘domestic pictures’ that

portrayed her as angelic, supportive and subservient

to the husband who, in all things, she willingly and

lovingly deferred…That anyway was the theory—a

pervasive form of patriarchy that permeated

Victorian society and culture. But of course the reality

was more complex. And in the underworld of crime

and corruption women played their part…

Cue the Forty Thieves later known as the Forty

Elephants: a syndicate of working-class women who

stole, blackmailed and extorted their way to notoriety.

Operating from the 18th and into the 20th century, it

was around 1890 that the gang fell under the

five years for her crimes.

Mary’s successor at the helm of the Forty Thieves was

Alice Diamond. Born inside the workhouse, Alice rose

through the criminal ranks to lead the gang with

military precision. She expanded their operation

beyond London; the motley crew (known for their

bewitching looks) travelled the country stealing and

plundering and hiding their loot up their skirts and

knickers.

All the while other women continued to subvert the

stereotype of the Angel in the House. Female

offenders were mainly responsible for minor crimes

such as theft and public disorder. There was a high

rate of female re-offending. Many were forced into

crime through abuse, poverty and destitution; sexual

exploitation was rife. And while women made up only

a small proportion of convicted offenders, their role in

crime was disproportionately discussed. In the press,

leadership of Mary Crane AKA Mary Carr, Polly Carr,

Polly Pickpocket, Handsome Polly and Queen of the

Forty Thieves. In Scoundrels and Scallywags, and

Some Honest Men (1929), Detective Tom Divall wrote:

‘She had rather small features and a luxurious crop of

auburn hair, but she was the most unfeeling criminal

that ever lived. She participated in child stealing,

enticing men into filthy and foul places, and in fact in

everything too horrible to mention. She had been an

artists’ model, and if she had stuck to that business

she might have done well and lived in luxury’.

Instead she wound up behind bars. Charged with

theft on numerous occasions, an 1896 conviction saw

her sentenced to three years penal servitude for

kidnapping a child. After her release Mary resumed

fencing stolen goods and in 1900 received another

the female criminal was depicted as the antithesis to

the Angel in the House: cold, calculating,

promiscuous and monstrous; in medical and legal

circles, she was morally corrupt and mentally

deficient.

Some women began writing about crime, taking aim

at the supposedly safe domestic sphere. Mary

Elizabeth Braddon’s sensational novel Lady Audley’s

Secret (1862) placed crime at the heart of the hearth,

provoking the worrying question: what if the Angel in

the House was secretly a Domestic Devil?

Such a concern captured the Victorian imagination.

And with poison in abundance—arsenic being

particularly ubiquitous in the first half of the century

— the potential for a domestic goddess turned

demonic murderess remained in the realm of

possibility.

CRIME AND THE UNDERWOLD / 23

John Woolf is the author of

Dr

FRY’S VICTORIAN

STEPHEN

and THE WONDERS:

SECRETS

THE CURTAIN ON THE

LIFTING

SHOW, CIRCUS AND

FREAK

AGE

VICTORIAN

Amelia Dyer (below) the

‘Baby Farmer’ poisoned,

starved and strangled

infants in her care—

killing around 400 in a

thirty-year period.

Were there not numerous cases that proved the

point? The twenty-two-year-old servant Eliza

Flemming executed for poisoning her master and his

family in 1815; Sarah Chesham executed for poisoning

her husband in 1851 And in 1873 Mary Ann Cotton

was sentenced to death for the destruction she

wrought with arsenic.

Previously a Sunday-school teacher and nurse, Mary

Cotton murdered a total of twenty-one people

between 1865 and 1872, making her far more prolific

than Jack the Ripper. She hid behind the image of

the Angel in the House to mercilessly murder three of

her four husbands, eleven of her thirteen children,

plus her lovers and her mother. Mary moved across

the north of England collecting the insurance after

the slaughter of her nearest and dearest. And on 24th

March 1873 she drew her last breath at the gallows in

Durham County Gaol: ‘She clasped her hands close to

her breast, murmured in an earnest tone, “Lord, have

mercy on my soul”, and in a moment the bolt was

drawn’.

Mary Cotton murdered a total of

twenty-one people between 1865

and 1872, making her far more

prolific than Jack the Ripper.

Cotton was by no means the only female serial killer.

Amelia Dyer the ‘Baby Farmer’ poisoned, starved and

strangled infants in her care—killing around 400 in a

thirty-year period. She too met her fate at the gallows

on 10 June 1896. Her last words: ‘I have nothing to

say’.

Dyer joined the pantheon of female murderers

executed for their crimes. And she emphatically

disrupted the Victorian notion of the Angel in the

House. It was always just a theory, and one which was

neither universal nor constant, but this maleconstructed

ideology captured a supposed ideal. It

was, however, bloodily subverted by the female

murderers and criminals who dispensed with the

Angel in the House and, in so doing, provoked fear

and loathing throughout Victorian society.

@drjohnwoolf

24 / CRIME AND THE UNDERWORLD

IMPROVE YOUR

BOOKSHELF WITH

INSIDE HISTORY

Affiliated with

www.insidehistorymagazine.co.uk/bookstore

SELF-MADE

MAN

THE

EVOLUTION OF

THE MYTH OF

H.H HOLMES

WORDS BY DR REBECCA FROST

On May 7, 1896, a man who had gone under the

name of H. H. Holmes was executed for the murder

of Benjamin F. Pitezel. That murder, and Holmes’

execution, both took place in Philadelphia, PA,

although he is today associated with Chicago and

the White City of the Columbian Exposition, thanks

to Erik Larson’s 2003 book. Although Holmes was

only ever put on trial for this single murder, Larson

presented Holmes – birth name: Herman Webster

Mudgett – as a serial killer who lured guests of the

Fair to his Murder Castle so he could take pleasure

in killing them.

In his lifetime, Holmes’ largest confession was to

twenty-seven murders. Some of those he named

came forward to argue that they were, in fact, still

alive, while others could not be proven to ever have

existed. As his very own first mythmaker, Holmes

would have approved of any tale that pushed that

tally into triple digits.

Holmes changed his own story continually during

his lifetime, along with his name, collecting a host

of biographies and pseudonyms. Between his final

capture in Boston in November 1894 and his

execution, he spoke three different confessions,

wrote an autobiography that protested his

innocence, and wrote his single written confession

of twenty-seven murders – although he used his

last words on the gallows to contradict himself yet

again.

"In his lifetime, Holmes’

largest confession was to

twenty-seven murders.

Some of those he named

came forward to argue

that they were, in fact,

still alive, while others

could not be proven to ever

have existed."

The “true” story of H. H. Holmes is further muddied

by the fact that newspapers ran their own

headlines and cobbled together their own

confessions from various sources. blurring facts and

adding to the confusion surrounding what Holmes

himself did, in fact, write or say.

In the twenty-first century, we have been exposed

repeatedly to the narrative of the serial killer in both

fact and fiction. Their stories are therefore

predictable: abusive mother, absent father, and

common childhood traits that it seems any

captured serial killer can adapt to his own

biography. Holmes, in the late nineteenth century,

had no such format. In order to sell his own story,

especially his autobiography in which he claims

innocence, he had to determine for himself what

plot elements would entice readers to pay twentyfive

cents for a copy.

Holmes’ Own Story, published in 1895, was

purportedly written by Holmes while he was

detained in Moyamensing Prison. The

autobiography even includes an appendix entitled

the Moyamensing Prison Diary in which Holmes

first details his day-to-day life as a prisoner and

then, finally, concocts his explanation for why so

many of the Pitezel family – Benjamin as well as

three of his children – were discovered to have died

after being around him. Holmes’ Own Story went to

press before Holmes was put on trial for Pitezel’s

murder, so he had to balance both the story of his

own innocence while competing for audiences’

attention with the lurid newspaper headlines

detailing his life, including such tantalizing tidbits

as bigamy and murder.

Moyamensing Prison, Philadelphia PA. The execution of H. H. Holmes,

scene while he was making his final address. Sketched in the Prison by

Newmar, Times artist. From Holmes' Own Story (1895) by Mudgett,

Herman W.

Credit: Wikmedia Commons

Even while in Moyamensing, Holmes was allowed

to read the paper. One morning, in fact, when he

awoke to a commotion outside, he sent for it

CRIME AND THE UNDERWORLD / 27

"As his very own first

mythmaker, Holmes

would have approved of

any tale that pushed that

tally into triple digits."

outward appearance and apparent affection for the

children, since he trusted Hatch and Miss Williams

both to care for them out of his own sight. Had

Holmes not allowed them to take the children,

then, he tells his readers, they would still be alive

today.

After being convicted of the murder of their father,

however, Holmes changed his story and included

the three Pitezel children as victims in his

confession to twenty-seven murders. He had

immediately and was able to read in the headlines

that the bodies of two of the Pitezel children had

been found even before the detective had been

able to make his way to the prison to question him

about them. Holmes was therefore not caught

unawares and had already had the chance to set

his story in order before confronting Detective

Geyer.

The papers also helped direct him to discover what,

exactly, was holding the public’s attention during

this pre-trial publicity, and Holmes then adapted

what he read into his autobiography by placing the

most scandalous traits on others. In Holmes’ Own

Story, Pitezel himself becomes a drunk who not

only fails to support his family monetarily but

discovers himself to have taken a second wife after

a night of serious drinking. Holmes himself was

rumoured to have taken – and murdered – a string

of mistresses, including Miss Minnie Williams,

whom he resurrected for his autobiography. Miss

Williams became a fallen woman who had freely

slept with multiple men before she met Holmes, a

seducer against whom he was powerless. To add

insult to injury, Holmes even included the idea that

the children’s deaths were, in fact, Miss Williams’

idea, and that she convinced her new paramour to

commit the murders and frame Holmes because

she was jealous of Holmes’ new wife. Holmes

himself, of course, repented of his weakness and

refrained from allowing himself to be overcome by

any other such fallen women, remaining faithful to

his – supposedly only – wife.

The majority of the murderous traits ascribed to

Holmes in the newspapers were transferred to the

fictitious figure of Edward Hatch. Hatch claimed to

be married to Miss Williams, a statement Holmes

indicates he suspects to be untrue and physically

resembles Holmes. This, of course, means that any

time a witness came forward to state that Holmes

had been seen with the children, the man in

question had actually been Hatch. Holmes himself

even laments that he was fooled by Hatch’s

already profited from the sale of his book and now,

just weeks prior to his execution, sold his new story

to the Philadelphia Inquirer – even though it, too,

soon proved to be false.

Holmes the con-man began creating his own tall

tale during his lifetime, and would be pleased that

he is still being spoken and written about today,

while the mystery remains: how many people did

he murder? It is a secret Holmes took to the grave.

28 / CRIME AND THE UNDERWORLD

"How many people did he

murder? It is a secret Holmes

took to the grave."

Above: World's Fair Hotel, better known as H. H.

Holmes Castle. Circa 1890's. Credit Wikimedia

Above right: August 11, 1895 Joseph Pulitzer's "The

World" showing floor plan of Holmes "Murder

Castle" and left to right top to bottom scenes found

inside it-including a vault, a crematorium, trapdoor

in floor and a quicklime grave with bones

Rebecca Frost is the author of

WORDS OF A MONSTER:

ANALYZING THEWRITINGS OF H.H

HOLMES, AMERICA'A FIRST SERIAL

KILLER

RRP: $29.95

CRIME AND THE UNDERWORLD / 29

Lizzie Borden took an axe and gave

her mother forty whacks. When she

saw what she had done, She gave her

father forty-one.

THE

TRIALS OF

LIZZIE

BORDEN

WORDS BY NICK KEVERN

In April 2015, Oak Grove Cemetery in Fall River

Massachusetts became the unusual place that

journalists found themselves flocking to. They were

there because a grave site was vandalised with green

and black paint. It was not the first time that the grave

site in question was targeted and indeed that of the

individual who laid beneath. Her name will forever be

linked to the double murder of her father and step

mother in 1892. She was the prime suspect who,

despite her acquittal for murder, would later became a

key part of America’s criminal history, spawning

movies, books, articles and even operas. Even today,

the curious can stay the night at her old house where

the now infamous crimes took place. The green and

black paint that defaced her final resting place was

simply another trial Lizzie Borden would face.

On the 4th August 1892, there was a frenzy of police

activity at 92 Second Street in Fall River, Massachusetts.

Upon their arrival the grim discoveries of the crime

scene awaited them. Upstairs, the body of Abby Borden

laid on the floor of the bedroom. The first blow hit her

at the side of her head with wounds that corresponded

with that of a hatchet being the most likely murder

weapon. 17 further blows continued ensuring that she

was dead. Her body was colder when compared to the

second victim with the police concluding that she was

the first to be murdered.

Downstairs the body of Andrew Borden was discovered

slumped on the couch in the sitting room. His face was

unrecognisable following his attack. Struck 11 times

with a hatchet to his head, police were convinced that

he was asleep as he was murdered. His body was still

bleeding from his wounds suggesting that it was a very

recent attack. They calculated his time death at

approximately 11 am.

Rumours would soon circulate in the press about the

double murders. Ranging from a “Portugeuse

Labourer” eager for his wages from Andrew Borden

Andrew Borden, father of Lizzie Borden, slain in his house in Fall River.

Police forensic photograph. 1892 The Burns Archive./ WikiCommons

being a suspect, to Abby Borden being attacked "by a

tall man who struck the woman from behind." The

appetite for coverage of the crimes was reaching

fever point. Two days after the murders, the media

had turned their attention to the Andrew Borden’s

daughter, Lizzie.

The media circus that surrounded the case would act

as the first of many trials for Lizzie Borden. Soon there

were reports that she had attempted to purchase

prussic acid the day before the murders from Eli

Bence who was a clerk at S.R Smith’s Drug Store. The

Boston Daily Globe would also report that Lizzie and

her stepmother were no longer on speaking terms.

Family members would however, contradict these

claims. The newspapers had their target firmly in

their sights.

The police were inclined to agree with the media.

Puzzled by the lack of blood anywhere except on the

bodies of the victims, they were convinced that the

murderer came from inside the household. The

suspicion was firmly with Lizzie. Her older sister,

Emma, was out of town during the time of the

murders and her uncle, John Morse (who was staying

with the Borden Family) was out visiting his nephew

and niece in town.

Further suspicion grew with Lizzie’s story. She

claimed that she was in the barn loft outside the

house preparing for an upcoming fishing trip yet the

dusty floor of the barn loft revealed no footprints. Her

" On the 22nd August at her

preliminary hearing, Judge

Josiah Blaisdell pronounced

her “probably guilty”

confused and contradictory answers at the inquest a

few days later led to her arrest. On the 22nd August at

her preliminary hearing, Judge Josiah Blaisdell

pronounced her “probably guilty”. It was enough for

her to face a grand jury at court for the murder of her

Father and stepmother.

During the trial itself, Lizzie never took the stand. The

vast majority of the case against her relied heavily on

circumstantial evidence with the defence offering

little in terms of hard evidence. It wouldn’t take long

for the Jury of 12 men to reach their verdict. With only

90 minutes of deliberation they found her “Not

Guilty”. In many cases, Borden would have been left

to continue her life peacefully but this was no

ordinary case. More questions were left than actual

answers. Even to this day the murders of Andrew and

Abby Borden remains unsolved. However, the mud

had firmly stuck to Lizzie as she now faced the trial of

public opinion.

CRIME AND THE UNDERWORLD / 31

The Borden murder trial—A scene in the court-room before the acquittal - Lizzie Borden,

the accused, and her counsel, Ex-Governor Robinson. Illustration in Frank Leslie's

illustrated newspaper, v. 76 (1893 June 29), p. 411.Credit: Library of Congress/Wikicommons

It would not take long for the first book about the

case to hit the bookshelves. “The Fall River Tragedy: A

History of the Borden Murders,” was written by Edwin

H. Porter who was a reporter for the Fall River Daily

Globe. Porter believed that Lizzie was guilty of the

crimes. Sold for $1.50, the book proved to be popular

as the case was still fresh in the public’s imagination.

For those who believed that Lizzie had gotten away

with murder, this book proved them to be correct.

For those who believed her to be innocent, it could

have possibly swayed them. No matter where Lizzie

would go, the case would never be far away. More

books would be released during Lizzie’s lifetime as

amateur and professional sleuths gave their opinions.

Lizzie never left Fall River. Opting to stay she would

soon become a pariah within the community. Having

moved to Maplecroft in the richer part of town she

undoubtedly heard the children singing the now

famous skipping rope about her. She was also later

detail. The film insinuates that there is a valid

explanation for the lack of blood anywhere other than

on that of the victims. It suggests that Lizzie

commited the murders whilst naked and bathing

after each murder. The same idea would later be

repeated in 2014 as Christina Ricci portrayed Borden

for a new generation.

“Lizzie” starring Chloe Sevigny and Kristen Stewart

was released in 2018. This interpretaion of the

murders implies that both Lizzie Borden and the

housemaid, Bridget Sullivan were both involved

suggesting that they were also intimate and that

Andrew had sexually abused Bridget.

As a new generation learns more about the murders it

is these interpretations that have continued to put

Lizzie Borden on trial even to the present day. There

will be more written and documented about the case

as time goes on as the trials of Lizzie Borden continue.

Photo from the made for television film "The Legend of Lizzie Borden

"starring Elizabeth Montgomery. 1975

Credit: WikiMedia

snubbed by the Christian Endeavor Society where

prior to the murders she had served as the treasurer.

Alienated from former friends and family members,

Lizzie often sat on the pew alone in church as the

community distanced themselves from her. At the

time of her death at the age of 66, the vast throng of

people attending her trial had dwindled to only a

handful of mourners at her funeral.

Discover more about Lizzie Borden

TRIAL OF LIZZIE

THE

A TRUE STORY

BORDEN:

Cara Robertson

by

published by Simon &

Now at peace, the trials of Lizzie Borden should have

ended but in reality they had only just begun. Such

was the interest in the murders it would not take

long for new areas of the media of regain an interest.

“The Legend of Lizzie Borden” starring "Bewitched"

actress Elizabeth Montgomery aired in 1975. A new

interpretation of the murder was revealed in graphic

Schuster

RRP: £15.99 Amazon

CRIME AND THE UNDERWORLD / 33

The Morellos:

Families at War

Words: Anthony Ruggiero

Images: WikiMedia

The Morello family was the United States’ earliest mafia

family, who were based in the Italian Harlem of Manhattan.

Giuseppe Morello founded the crime group during the

1890’s after his had migrated from Sicily to New York. Prior

to living in the United States the Guiseppe had already

began engaging in criminal activity, which forced them to

move to the United States. This mafia family was into

different types of criminal activities such as murder,

conspiracy, extortion, counterfeiting and racketeering.

However, following a series of legal problems and later the

Mafia-Camorra war, the gangs power began to rapidly

decrease. Regardless of this, the group had a significant

impact on organized crime in the early twentieth century.

Prior to immigrating to the United States the family had

already been involved in criminal activity. Giuseppe

Morello was born on May 2nd, 1867 in Corleone, Sicily. His

father, Calogero Morello, had died when he was five years

old, after which his mother, Angelina, got remarried to a

Corlonesi mafia member named Bernado Terranova. It

was Terranova who had introduced Sicilian mafia to

Morello. Like other Mafia members, Morello was forced to

leave Sicily in 1892 and went to the U.S. Another reason

cited for his immigration was being a suspect for

murdering and running a counterfeiting ring. Even

though, he reached the U.S., back in Sicily, the Italian

government had found him guilty of counterfeiting case.

In his absence, he was found guilty in September 1894 and

was sentenced to imprisonment for 6 years. Hence, he

never came back to Italy.

Giuseppe Morello arrived in New York from Corleone in

1892. He was followed six months later by his mother, stepfather,

four sisters and his step brothers; Nicola, Circo,

Vincent Terranova The family stayed in New York for a year,

but after failing to find any work they travelled to

Louisiana. For a year Morello worked with his father

planting sugar cane before moving on to Bryan, Texas

where he found work as a cotton picker. However, after

Louisiana was struck with a malaria epidemic in 1896, the

family relocated back to New York. In New York, Morello

worked with his father as an ornamental plasterer, with his

step brothers. He eventually opened a coal basement, but

quickly sold it, and in 1900 he opened a saloon on 13th

Street, soon followed by a second saloon on Stanton

Street. Due to bad business, Morello closed the Stanton

Street saloon and sold the one on 13th Street in 1901.

Ignazio Lupo, who would later become a powerful

member of the gang and also marry into the family,

arrived in New York in 1898. Lupo was fleeing arrest in

Palermo after killing a business rival in the wholesale

grocery business.

The gang’s early focus was on counterfeiting US currency.

This would ultimately result in them becoming the focus

of the New York Secret Service branch, with agents

specially trained to detect bogus bills and tracking down

street pushers with the hope of capturing the counterfeit

manufacturers. The first major arrests happened on June

11th, 1900, when Giuseppe Morello was captured along

with Colagero Meggiore. They were accused of selling

counterfeit money and held on $5000 bail. The arrests had

grown out of a Secret Service investigation that began

when counterfeit $5 bills were being passed in Brooklyn

and North Beach. Morello and Meggiore were believed to

be the suppliers of the money, which was described as

‘being printed on very poor paper with crude

workmanship’. However, due to their being a lack of

evidence, Morello was able to avoid any jail time.

However, legal troubles still continued for Morello, when

an anonymous letter was sent to Detective Petrosino of

the NYPD, the Secret Service raided a powerful band of

counterfeiters on May 22nd, 1902. The letter claimed that a

gang had been manufacturing coins at a cottage in

Hackensack, New Jersey, rented by Salvatore Clemente, an

acquaintance of Nicholas Terranova. Agents also raided a

barbershop that was being used to distribute the currency,

which resulted in the arrests of Vito Cascioferro and

Giuseppe Romano. Cascioferro was one of the most

34 / CRIME AND THE UNDERWORLD

GIUSEPPE MORELLO 1902

IMAGE: WIKICOMMONS

powerful Mafia leaders of the time; he managed to escape

conviction with an alibi that he worked at a local paper

mill. The alliances that Morello formed in these

counterfeiting were of mixed ethnicities. The 1900 arrests

were a mixture of Italians and Irish criminals. Working with

already established gangs in New York was a necessity due

to the technical, mechanical, and network requirements of

the counterfeiting business.

Giuseppe Morello started a real estate company in 1902,

‘The Ignatz Florio Co-Operative Association Among

Corleonesi’; the company was involved in the construction

and selling of properties in New York. The names listed on

the incorporation as directors were Morello, Antonio

Milone – a man who would later be involved with their

counterfeiting schemes and Marco Macaluso. The

company eventually collapsed, hindered by the economic

downturn in 1907. The Bankers Association of America

later investigated it. In 1902 Morello acquired a saloon on 8

Prince St. in Manhattan, which became the official

meeting place for the gang. From Prince St. Morello

launched his empire employing several enforcers whose

Another major event that placed the Morello gang in the

eyes of the public was The Barrel Murder in 1903.

According to the The New York Times, on April 14th, 1903, a

barrel was discovered with a man’s body inside. The body

was been gruesomely mutilated. Police believed the barrel

that had once been used for shipping sugar was dumped

from the back of wagon in the early hours. On the base of

the barrel was stenciled ‘W.T’, and on the side “G 228”. The

victim was thought to have been from a fairly prosperous

background, due to his “clean person, good clothes and

newly manicured nails”. The following day, Secret Service

agents, who had been tracking the Morello gang for over a

year in connection with counterfeiting, claimed to have

seen the victim with various members of the gang in a

butcher’s shop in Stanton Street on the evening of

Monday, April 13th.

As a result on April 15th, eight members of the Morello

gang were arrested. The police had been watching the

gangs usual hangouts: a Stanton Street butcher shop, a

cafe at Elizabeth Street and a saloon Prince Street in

Manhattan. Each member of the gang was found to

Fifth Avenue in New York City on Easter Sunday in 1900 (Wilimedia)

sole job was to kill anyone Morello requested. For example,

Guiseppe Catania, a Brooklyn grocer, was found murdered

on July 23rd, 1902. The Secret Service believed that Catania

had been a member of the Morello gang involved with

counterfeiting. They suspected the gang had disposed of

him due to his habit of drinking, talking too much, and

had argued with gang members whom he had fights over

debts owed to them. It was later revealed by the Secret

Service that Morello had Catania killed.

Further legal problems continued in January 1903, Morello

was charged with passing counterfeit money. It was

discovered that $5 bills were being replicated in precise

imitation to the currency issued by the National Iron Bank,

Morristown, NJ. They were printed in Italy and shipped to

New York in empty olive oil cans. Other suspects refused to

implicate Morello in the case and he walked free. Several

members of the Morello gang were sent to prison,

including Giuseppe De Primo.

armed, with either a knife or a pistol. The members that

were arrested included Giuseppe Morello, Tommaso Petto,

Joseph Fanaro, Antonio Genova, Lorenzo LoBido, Vito

LoBido, Dominic Pecoraro, and Pietro Inzerillo. When

Morello was interrogated and later taken to view the body

in hopes that he would identify whom the person was he

refused, and it was widely feared that Morello and his gang

would be released because there was no evidence to hold

them in police custody. However, police continued

searching and would soon locate where they thought the

murder had been committed. It was a pastry shop on

Elizabeth Street in Manhattan called, Dolceria Pasticceria,

run by Pietro Inzerillo, it was there they found an identical

barrel to the one used in the murder, even bearing the

same inscriptions. Sawdust, and some burlap, on the floor

of the shop had also been found in the base of the murder

barrel. The barrel was eventually traced to Wallace &

Thompson bakery, where their record books showed an

entry of a sugar order, made by Pietro Inzerillo in February

of that year. Thus, police continued to investigate the

situation further.

36 / CRIME AND THE UNDERWORLD

Eventually, the body was identified as Benedetto Madonnia,

the brother-in-law of Giuseppe De Primo, who identified his

body and was still imprisoned by counterfeiting money

since January of that year. De Primo revealed that Madonnia

was not part of any counterfeiting scheme and had lived in

Buffalo, New York. He revealed that he had traveled down to

Manhattan to collect $25,000 dollars owed to De Primo and

suspects that the gang killed him instead of giving him the

money. However, despite this admission by De Primo, this

was not enough to detain Morello and six other of his

associates. Initially, on April 25th, Tommaso Petto was

formally charged with committing the murder. Petto, when

arrested on April 15th, had been found in possession of pawn

ticket number, dated April 14th 1903. The ticket had been

traced to a watch that had belonged to the murder victim

that had been described to by the victim’s stepson to the

police. However, this was the only evidence that police

would find linking Petto to Madonnia’s murder and he too

was later released from prison on January 29th, 1904.

Although, the gang and its leader were able to avoid any

serious conviction despite committing numerous offences,

it was not long before Giuseppe Morello would be arrested.

On November 15th, 1909, Secret Service agents met with

officer Carraro from the police and went to Morello’s home

where they arrested him in connection with a counterfeiting

operation in Highland, New York. According to police

reports he was taken from his bed Morello and placed in the

front room with his son while agents searched the house.

While the were searching his home, Morello passed two

letters to his wife to hide, however Carraro discovered them,

Carraro and the agents would later find four more letters

hidden inside a baby’s diaper. A Secret Service agent, Flynn,

described what a letter would entail and how it was used:

A threatening letter is sent to a proposed victim.

Immediately after the letter is delivered by the postman

Morello just “happens” to be in the vicinity of the victim to

be, and “accidentally” meets the receiver of the letter. The

receiver knows of Morello’s close connections with Italian

malefactors, and, the thing being fresh in mind, calls

Morello’s attention to the letter. Morello takes the letter

and reads it. He informs the receiver that victims are not

killed off without ceremony and just for the sake of

murder. The “Black-Hand” chief himself declares he will

locate the man who sent the letter, if such a thing is

possible, the victim never suspecting that the letter is

Morello’s own. Of course, the letter is never returned to the

proposed victim. By this cunning procedure no evidence

remains in the hand of the receiver of the letter should he

wish to seek aid from the police.

These letters and others discovered linking him to the

counterfeiting operation in Highland, New York was enough

evidence to finally convict Morello, thus sending him to

prison.

With Morello in prison, new leadership of the Morello gang

needed to be decided. There were the Terranova brothers,

Ciro, Vincent and Nicholas who were highly considered.

Other possible candidates included the Lomonte brothers,

Fortunato and Tomasso, the cousins of Giuseppe Morello.

They operated a hay and feed business in Manhattan.

Giuseppe Morello’s young son, Colagero was also in

consideration for leadership of the gang. However, the

Terranova brothers soon left the gang after failing to

secure leadership and formed their own gang called “The

White Doves.” Rocco Tapano, whose uncle, Benedetto

Madonnia, had been killed by the gang years earlier, killed

Colagero in 1912 in retaliation of the murder. Nicholas

Terranova later killed Tapano for Colagero’s murder.

Fortunato Lamonte, who had began to increase his power,

was killed in 1914 by associates of ‘Toto’ D’Aquila, a mob

moss in the Gambino crime family, who was looking to

remove Lomonte from gaining too much power. He also

had him killed for the recent killing of D’Aquila’s friend,

Giuseppe Fontana, a long time Morello associate who had

left the gang. Overall, this time period was filled with

much turbulence for the once powerful gang.

Chaos ensued following the start of the Mafia-Camorra

War. The Camorra was a large coalition of mafia groups,

who were all from Naples, Italy. The situation began to

escalate on June 24th 1916 when a meeting took place at

Coney Island between the Morello gang, the Neapolitan

gang and the Neapolitan Coney Island gang. The idea of

the meeting was to negotiate the expansion of gambling

dens in lower Manhattan. Even though the Morello’s and

the Navy Street gang worked together for sometime,

including jointly removing, Giosue Gallucci, a crime boss

once affiliated with the Camorra, from Harlem, the

Neopolitans believed they could have taken over the

Harlem rackets if they could eliminate the Morellos. They

devised a plan where they would attempt to lure the

entire leadership down to Brooklyn and ambush them. On

September 7th 1916, Nicholas Terranova and Charles

Ubriaco travelled downtown to meet with the Navy Street

gang; they were both ambushed and killed.

The Morello gang and the Brooklyn Camorra were officially

at war. The Camorra conducted various plans to take out

the rest of the Morello leadership, but they were either

discovered or were never completed, however the

Camorra in Philadelphia would later murder four

associates of the Morello gang. The Navy Street gang

managed to take over the Morello businesses for a short

period in 1918. A Harlem gambler claimed that for a short

duration he had to travel to Brooklyn each week to have

his books checked. The Camorra even tried to move in on

the Morello’s artichoke business, but the wholesale dealers

refused to give in to their threats. Although, eventually the

two sides met a deal where a ‘tax’ of twenty-five dollars

was paid on every carload of artichokes that were

CRIME AND THE UNDERWORLD / 37

delivered. Coal and ice merchants who had worked with

the Morellos also proved hard to threaten, and the

Camorra’s did not profit much from this corporate takeover

then they had imagined. At this point the Morello gang had

been defeated and D’Aquila was the new major crime boss.

However things would once again shift in the Morello

gang’s favor when, in 1920, Giuseppe Morello was released

from prison after serving ten years of his fifteen year

sentence. By this time former Morello crime family

member, Giuseppe “Joe the Boss” Masseria had gained

influence over several gangs and become very powerful.

After aligning himself with former loyal gang members,

Morello unsuccessfully attempted to have Masseria killed.

Due to his unsuccessful attempts Morello would align

himself with Masseria and the rising organized crime

leader, Lucky Luciano. However, Giuseppe Morello would

later be gunned down in 1930, thus never being able to fully

regain the prominent status the gang once possessed.

The Morello gang was significant group that had a

significant impact on organized crime in the early

twentieth century. During their prominence, the gang

managed to make headlines in the media for their

counterfeiting schemes and murders in which a majority of

its membership managed to avoid conviction for a period

of time. Although, the group would eventually collapse

following the fall of their leader and founder, their inability

to establish new leadership, and its lost to the Camorra; the

gang will always be remembered as the first major

organized crime group in American history.

Giuseppe Morello would

later be gunned down in

1930, thus never being

able to fully regain the

prominent status the gang

once possessed.