Optimum Nutrition - Summer 2020 PREVIEW

Dr Andrew Jenkinson, bariatric surgeon and author of Why We Eat (Too Much), talks to us about why diets don't work, what we can do about it, and why obesity is linked to a higher risk of severe COVID-19 symptoms | Behind the virals: we explore the anti-COVID-19 remedies circulating on social media | The links between nutritional deficiencies and COVID-19 mortality rates | All about inflammation: what it is, why we need it and what happens when it creates a storm | How those sugary lockdown treats may be affecting your mental health | Personalised exercise: are we natural born winners? | Plus: kids pages, recipes and more!

Dr Andrew Jenkinson, bariatric surgeon and author of Why We Eat (Too Much), talks to us about why diets don't work, what we can do about it, and why obesity is linked to a higher risk of severe COVID-19 symptoms | Behind the virals: we explore the anti-COVID-19 remedies circulating on social media | The links between nutritional deficiencies and COVID-19 mortality rates | All about inflammation: what it is, why we need it and what happens when it creates a storm | How those sugary lockdown treats may be affecting your mental health | Personalised exercise: are we natural born winners? | Plus: kids pages, recipes and more!

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

THIS ISSUE<br />

16<br />

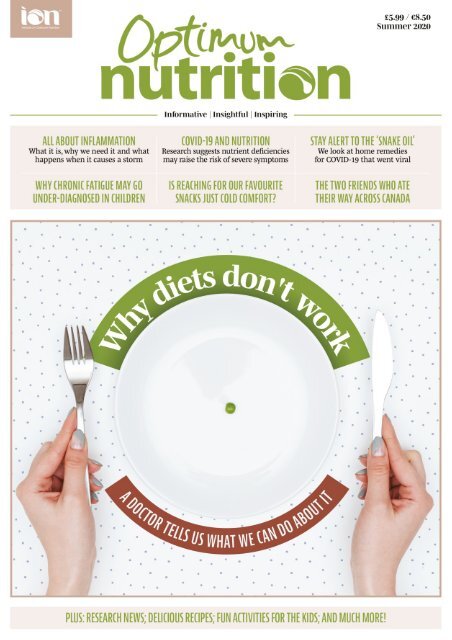

Interview<br />

Bariatric surgeon Dr Andrew Jenkinson talks to Alice Ball about why diets don’t work and what we can do about it (without surgery)<br />

08<br />

36<br />

Research update<br />

Recent research suggests that low levels<br />

of some nutrients may be implicated in a<br />

higher risk of severe COVID-19 symptoms<br />

or risk of mortality from the disease<br />

24 Little lives<br />

Why some experts believe that “stigma<br />

and misunderstanding” among doctors is<br />

causing under-diagnosis of chronic fatigue<br />

syndrome (CFS/ME) in children<br />

Feature<br />

Sugary snacks can be soothing during<br />

difficult times, but could reaching for fruit<br />

and veg be better for our mental health,<br />

long-term? Louise Wates writes<br />

46 Different strokes<br />

COVID-19 has raised concerns that<br />

smokers, should they catch it, could be<br />

hard-hit by the disease. Elettra Scrivo<br />

looks at ways to quit<br />

Contents<br />

12 Feature<br />

COVID-19: Stay alert to the ‘snake oil’.<br />

Alice Ball looks at some of the home<br />

remedies that went viral and finds out if<br />

they are helpful, toxic or a waste of time<br />

28<br />

Little lives<br />

As we try to deal with the ‘new normal’,<br />

many parents are putting on brave faces<br />

despite anxiety and worry. But could this<br />

have an unintended effect?<br />

40 World cuisine<br />

When it comes to cuisine, Canada is<br />

home to much more than maple syrup<br />

and butter tarts, as two friends discovered<br />

on the trip of a lifetime<br />

20<br />

48 Move it 50<br />

Giulia Basana asks whether knowing<br />

about our DNA can help us to improve our<br />

fitness levels, or whether it’s environment<br />

that wins the day<br />

45<br />

All about<br />

Inflammation: Louise Wates looks at what<br />

it is, why the body needs it, and why it<br />

can become a problem when it creates a<br />

storm<br />

30<br />

On your plate<br />

Try three vibrant recipes from around<br />

the world and a take on a children’s<br />

teatime favourite, from The mymuybueno®<br />

Cookbook by Justine Murphy<br />

Food fact file<br />

We look at some of the potential health<br />

benefits associated with walnuts — and if<br />

you don’t know what to do with them, try<br />

our recipes to get you started<br />

Graduate story<br />

Olga Hamilton tells us how redundancy<br />

gave her the freedom to study nutritional<br />

therapy, taking her to a new and varied<br />

career — and even delivering a Tedx talk<br />

04 Comment / news | 19 Book therapy | 26 Kids’ pages<br />

34 Product news | 39 Kitchen chemistry | 45 In season<br />

SUMMER <strong>2020</strong> | OPTIMUM NUTRITION<br />

3

INTERVIEW<br />

Dr Andrew Jenkinson talks to Alice Ball about the complexities of weight-loss and how he<br />

hopes the current pandemic will inspire a major public health campaign on obesity<br />

16 OPTIMUM NUTRITION | SUMMER <strong>2020</strong>

INTERVIEW<br />

W<br />

hen we meet over a video call,<br />

Dr Andrew Jenkinson, author<br />

of Why We Eat (Too Much): The<br />

New Science of Appetite, is on his day<br />

off as a bariatric and general surgeon<br />

at University London College Hospital.<br />

The UK is in the midst of lockdown and<br />

a subject close to Jenkinson’s heart<br />

— obesity — is in the news. Evidence<br />

reveals obesity to be one of the risk<br />

factors for severity of COVID-19; a stark<br />

reality for the UK. According to latest<br />

NHS figures, 64 per cent of adults in<br />

England alone are overweight or obese,<br />

and 29 per cent are obese. 1 However,<br />

obesity can be a difficult subject to<br />

discuss.<br />

“At the moment, the perception of<br />

anyone who’s fat is that it’s their choice,”<br />

says Jenkinson.<br />

Yet it is not a view that he holds,<br />

despite having performed weight-loss<br />

surgery on more than 3,000 patients<br />

over two decades. Instead, Jenkinson<br />

is sympathetic towards those who are<br />

struggling with their weight — something<br />

that he says wasn’t always the case.<br />

Not only are there some people who are<br />

genetically predisposed to gaining weight<br />

more easily, he points out, but he is also<br />

critical of the western diet. “A western<br />

diet causes a population to become<br />

fat and have cardiovascular disease,”<br />

he says. “That is then a serious risk for<br />

having complications from coronavirus.”<br />

One of the links between obesity<br />

and a higher risk of severe COVID-19<br />

symptoms is oxidative stress; an<br />

inflammatory state characterised<br />

by an imbalance of free radicals and<br />

antioxidants that leads to cell damage —<br />

including to the immune system’s T cells,<br />

making them less effective.<br />

“[The virus] attacks the S2 receptor<br />

in our lungs and cardiovascular system,”<br />

he explains. “The S2 receptor is really<br />

important in…oxidative stress. If S2 is<br />

malfunctioning, we have more oxidative<br />

stress which can cause cardiovascular<br />

disease, clotting problems, cardiac arrest<br />

and respiratory problems.”<br />

Jenkinson says that many people in<br />

western countries already have oxidative<br />

stress due to western diseases such as<br />

obesity, and are more susceptible to<br />

becoming critically ill if they do catch the<br />

virus.<br />

Yet for anyone who wants to lose<br />

weight, Jenkinson does not believe that<br />

going on a diet is the answer. He isn’t<br />

swift to recommend bariatric surgery<br />

either. Published in January, his book<br />

explores the concept of weight set-point<br />

and why this causes diets to fail. Many<br />

dieters may be familiar with the idea, at<br />

least in a hypothetical sense, when they<br />

find that whatever they do to lose weight,<br />

their body seems to be hell-bent on<br />

getting back to where it was.<br />

First proposed by researchers in<br />

America, the concept of a weight<br />

set-point suggests that the body is<br />

programmed to maintain a weight<br />

range — and will fight to do so. However,<br />

Jenkinson says this description of weight<br />

set-point was “quite simplified” and<br />

didn’t fit with real life. His experience<br />

of patients, along with research into the<br />

relationship between the gut and the<br />

brain being carried out by colleagues at<br />

University London College Hospital, led<br />

him to expand on the idea.<br />

“There is a homeostasis or a<br />

negative feedback,” he says. “The body<br />

can increase or decrease its energy<br />

expenditure depending on how much<br />

excess fat or excess energy storage<br />

you’ve got.”<br />

What this means, he explains, is that<br />

the more diets you’ve been on, the higher<br />

your weight set-point will rise and the<br />

slower your metabolism will become,<br />

as your body fights to protect itself<br />

from future ‘famine’. Essentially, says<br />

Jenkinson, dieting is counterproductive<br />

to weight-loss.<br />

It’s this knowledge, he says, that<br />

gave him a new-found empathy when<br />

interacting with clients. They, in turn,<br />

responded positively to his explanation<br />

as to why they were trapped in their<br />

condition. Now he is a “total geek” about<br />

appetite and metabolism, having spent<br />

five years researching everything he<br />

could. “The patient’s stories were really<br />

my inspiration,” he says.<br />

Yet when Jenkinson started out as<br />

a doctor, he had no interest in obesity<br />

and it wasn’t a conscious decision<br />

to go into bariatric surgery. “When I<br />

was at medical school, obesity wasn’t<br />

a major problem and my interest in<br />

diet and nutrition was zero. I guess<br />

you sort of fall into things.” He recalls<br />

receiving “maybe an hour’s worth” of<br />

lecture time on weight regulation while<br />

...many people in western countries already have oxidative stress due<br />

to western diseases such as obesity...<br />

“...the figures don’t add up. How can people eat so much and not put<br />

weight on? It’s the same when people starve themselves and don’t<br />

lose as much weight as they want”<br />

studying at Southampton Medical<br />

School. “Medics aren’t taught much<br />

about it,” he says. “What we are taught<br />

is a very old fashioned and simplified<br />

way of how people can lose weight; just<br />

energy in and energy out. We look at<br />

different systems such as the respiratory<br />

breathing system and the urinary system,<br />

but we don’t study the weight regulation<br />

system.”<br />

He admits that in his first few years as<br />

a bariatric surgeon, he was prejudiced<br />

towards his patients’ problems. “I think I<br />

had a very similar preconception to most<br />

people in society,” he says. “Why have<br />

you got no willpower? Why don’t you get<br />

help and sort yourself out? I was quite<br />

judgemental before the penny dropped.”<br />

As months and years passed, however,<br />

his outpatient clinic became increasingly<br />

swamped with patients telling a similar<br />

tale: they’d tried to lose weight, but every<br />

time they did the weight crept back on —<br />

and then some.<br />

“When you’re hearing these stories all<br />

the time, you start to think that maybe<br />

there’s something they’re saying that we<br />

don’t understand.”<br />

What didn’t make sense to Jenkinson<br />

was that if the dogma of calories in,<br />

calories out was correct, people should<br />

have actually been much bigger. In<br />

the book he writes that looking at the<br />

evidence for how much people eat and<br />

analysing it with a very simplified energy<br />

in and energy out formula, we should be<br />

putting on four stone a year. “Obviously<br />

something is happening because the<br />

figures don’t add up,” he says. “How can<br />

people eat so much and not put weight<br />

on? It’s the same when people starve<br />

themselves and don’t lose as much<br />

weight as they want.”<br />

Investigating these questions, his<br />

book explores not only metabolism and<br />

genetics. It also explores the evolution of<br />

how humans ate up until what he calls<br />

the “industrialisation of food”.<br />

“Finally, you have the hijacking of our<br />

food advice by scientists who were paid<br />

by the food industry,” he says, echoing<br />

many other healthcare professionals who<br />

worry that big business wields too much<br />

influence over dietary advice. Jenkinson<br />

has what he calls a “healthy cynicism”<br />

for research. He suggests, for example,<br />

that in the west we became scared of<br />

saturated fat because of industry bias.<br />

“The sugar industry would give payments<br />

SUMMER <strong>2020</strong> | OPTIMUM NUTRITION<br />

17

ALL ABOUT<br />

Most of us will have taken anti-inflammatory medication at some point in our life, but what is<br />

inflammation? Why do we get it? And is it really always a bad thing? Louise Wates writes<br />

M<br />

any<br />

of us will have heard the term<br />

‘inflammatory disease’ for the<br />

first time during the pandemic.<br />

Notably, it was used when small numbers<br />

of children in Europe and the USA were<br />

reported to have fallen ill with a rare illness<br />

linked to COVID-19, displaying symptoms of<br />

toxic shock syndrome. The Lancet described<br />

the condition as a “Kawasaki-like disease”;<br />

20 OPTIMUM NUTRITION | SUMMER <strong>2020</strong>

ALL ABOUT<br />

likening it to a rare condition that was first<br />

identified in 1960’s Japan. But that doesn’t<br />

tell us anything about inflammation.<br />

If you have ever taken an ibuprofen then<br />

you have taken an anti-inflammatory. In<br />

fact, the over-the-counter and prescription<br />

market is awash with various types of<br />

anti-inflammatory medications — which<br />

surely tells us that inflammation must be<br />

a bad thing. Although, in itself, it isn’t. In<br />

fact, inflammation is an essential part of the<br />

immune system and the healing process.<br />

Acute vs. chronic<br />

If we bash a knee or cut a finger, the affected<br />

area may become hot and swollen. These<br />

are signs that the body’s immune system is<br />

on the case, deploying white blood cells to<br />

protect the injured area and to get rid of any<br />

damaged cells.<br />

This is acute inflammation in action,<br />

which should pass once the body has<br />

healed. Without it, we wouldn’t survive.<br />

Chronic inflammation, however, is<br />

associated with metabolic syndrome<br />

and a variety of other diseases including<br />

heart disease, rheumatoid arthritis, stroke,<br />

inflammatory bowel disease, cancer, and<br />

Alzheimer’s. While all of these diseases are<br />

rooted in a variety of causes, inflammation<br />

will have been present, potentially for a long<br />

time, before the disease ‘appeared’.<br />

Just like acute inflammation, chronic<br />

inflammation is triggered by some form of<br />

harm or ‘insult’ that activates the immune<br />

system. However, rather than standing<br />

down once the harm is no longer present<br />

(such as after a one-off bash on the knee)<br />

and once the body has healed, the immune<br />

system remains activated as it continues<br />

to tackle persistent problems such as, for<br />

example, regular exposure to toxins such as<br />

tobacco smoke, air pollution or chemicals.<br />

Whereas the example of a bash on the knee<br />

is a short-term, one-off insult to the body,<br />

many factors such as tobacco smoke or air<br />

pollution are often regular, daily insults that<br />

the immune system cannot resolve because<br />

the problem does not go away. Imagine<br />

what it would feel like if you bashed your<br />

knee every hour, every day. The immune<br />

system would be constantly activated yet<br />

the injured knee wouldn’t properly heal.<br />

Pro-inflammatory<br />

This is a very simplistic explanation<br />

of inflammation and of how different<br />

types of harm can contribute to chronic<br />

inflammation without us realising. Even<br />

conditions that are thought of as illnesses in<br />

themselves, such as high cholesterol, may<br />

occur because of inflammation. In 2017,<br />

for example, a trial of an anti-inflammatory<br />

drug found that the drug reduced the risk<br />

of heart attack, cardiovascular-related<br />

INFLAMMATION AND THE BRAIN<br />

Inflammation can affect every part of the human body, including the brain, becoming<br />

a factor in diseases such as depression, dementia and Alzheimer’s. One recent study<br />

suggested inflammation is an underlying cause of ‘brain fog’, which is often described as<br />

sluggishness or mental fatigue. 3 In a controlled study, 20 volunteers were injected with<br />

either a placebo or a salmonella typhoid vaccine, which causes temporary inflammation<br />

but has few other side effects. After being tested for cognitive responses, it was found that<br />

when the volunteers received the vaccination, inflammation affected brain activity related to<br />

staying alert.<br />

Another study, carried out on mice, found that in the presence of systemic inflammation,<br />

the brain’s immune cells (microglia) initially protect the blood-brain barrier before going into<br />

hyperdrive and attacking it. 4 The blood-brain barrier prevents potentially harmful molecules<br />

reaching the brain. The attack from microglia causes permeability, however, enabling<br />

molecules into the brain where they can cause widespread inflammation and damage to<br />

neurons (cells of the nerves). Although plaques and tangles in the brain have long been<br />

associated with Alzheimer’s, experts now say that it is inflammation — caused by plaques<br />

and tangles — that kills neurons and leads to cognitive decline.<br />

Another study that looked at brain scans of veterans who had served in the 1991 Gulf War<br />

found that veterans who suffered from Gulf War Syndrome (GWI), compared with healthy<br />

controls and veterans without GWI, had extensive inflammation “particularly in the cortical<br />

regions, which are involved in ‘higher-order’ functions, such as memory, concentration and<br />

reasoning”. 5<br />

Although the cause of GWI is still unknown, possible causes have been identified as<br />

exposure to nerve gas (as well as medicine given to protect against nerve gas); exposure to<br />

pesticides; and stress from extreme temperature changes, sleep deprivation and physical<br />

exertion. 5 Symptoms include fatigue, chronic pain, and cognitive problems such as memoryloss.<br />

According to the study’s authors, neuroinflammation in veterans with GWI looks very<br />

similar to widespread cortical inflammation also detected in fibromyalgia patients.<br />

death or stroke despite having no impact<br />

on cholesterol levels. 1 This indicated that<br />

inflammation — rather than high cholesterol<br />

— was the risk factor for heart attack and<br />

stroke. An implication, therefore, is that<br />

raised cholesterol (unless somebody has an<br />

hereditary predisposition for it) may be a<br />

response to disease rather than a cause.<br />

Obesity<br />

In the UK, possibly one of the leading<br />

causes of chronic inflammation is metabolic<br />

syndrome, which combines obesity, high<br />

blood pressure and type 2 diabetes. Obesity<br />

is particularly problematic with the presence<br />

of visceral fat. This is the fat that wraps<br />

around internal organs and can give us a<br />

bigger tummy; although even slim people<br />

can have it without knowing because it isn’t<br />

as obvious as subcutaneous fat, which lies<br />

under the skin. Visceral fat is associated<br />

with various health problems, one being the<br />

production of pro-inflammatory cytokines.<br />

(Cytokines are molecules that spread<br />

throughout the body and signal the immune<br />

system.) For example, according to one<br />

2016 study, overeating causes visceral fat<br />

cells to become stressed, causing them to<br />

produce pro-inflammatory cytokines which<br />

then go on to attack healthy cells. 2<br />

This particular study highlighted the<br />

role that weight and diet can play in<br />

inflammation. However, inflammation<br />

can occur even in the absence of<br />

obesity because even those of us who<br />

are at a healthy weight can suffer from<br />

inflammatory diseases.<br />

What we eat, as well as how much, is also<br />

an important contributor to inflammatory<br />

disease. A pro-inflammatory diet is<br />

usually considered to be one high in sugar<br />

and unhealthy fats such as trans fats. Its<br />

opposite — an anti-inflammatory diet,<br />

rich in antioxidants — is considered to be<br />

high in good quality protein, healthy fats,<br />

vegetables, legumes, fruits, nuts and seeds.<br />

The is also mounting evidence for the<br />

health benefits of such a diet. In 2019, one<br />

study looking at 1,852 cases of colorectal<br />

cancer and 1,567 cases of breast cancer<br />

(against 3,447 and 1,487 control cases,<br />

respectively) found a correlation between<br />

both diseases and a pro-inflammatory diet,<br />

with a strong association for increased<br />

colorectal cancer risk. 6 Although the study<br />

did not investigate the reasons why diet<br />

might affect inflammation and disease, the<br />

authors pointed to “inflammatory potential”.<br />

Increasingly, this is something that is<br />

linked to the western diet, which is high in<br />

processed and fast foods.<br />

Empty calories<br />

Unless they are fortified, many processed<br />

foods common to the western diet are high<br />

in calories and low in nutrients such as fibre,<br />

essential fatty acids, vitamins and minerals,<br />

leading to the description of ‘empty calories’<br />

SUMMER <strong>2020</strong> | OPTIMUM NUTRITION<br />

21

ON YOUR PLATE<br />

Prawns<br />

with chilli,<br />

ginger<br />

and garlic<br />

butter<br />

Serves: 4<br />

Justine says:<br />

“Cooked on the barbecue or griddle,<br />

these are quick and easy to prepare, and<br />

a wonderful way to enjoy prawns and get<br />

stuck in.”<br />

Ingredients<br />

• 100 g unsalted butter, chopped and<br />

softened<br />

• 2 cloves of garlic, peeled and grated<br />

• 1 cm ginger, peeled and grated<br />

• ½ red bird’s eye chilli, finely chopped<br />

• ½ tsp flaked sea salt<br />

• 1-2 tbsp fresh parsley, finely chopped<br />

• 1 tbsp sunflower oil (Our swap: olive oil)<br />

• 16 large raw prawns, deveined with<br />

shells on<br />

• Grind of black pepper<br />

• 1 lemon, cut into wedges<br />

Method<br />

Place the butter, garlic, ginger, chilli, and<br />

salt in a small saucepan over a medium<br />

heat until the butter is bubbling. Remove<br />

from the heat and stir in a tbsp of chopped<br />

parsley. Heat a barbecue or griddle pan and<br />

using a silicone brush, brush the grill rack<br />

or pan with the oil.<br />

Thread the prawns onto 16 metal<br />

skewers from the tail, so the heads are at<br />

the top of the skewer. Place each prawn<br />

skewer on the heat and cook for 3 mins<br />

on each side, until they are pink and you<br />

can see some charring. Brush the prawns<br />

while cooking with your flavoured butter.<br />

If they are really large prawns, you can<br />

cook them for a little longer, but it’s<br />

better to undercook fresh prawns, as the<br />

residual heat will finish the process, than<br />

to overcook them, making them hard and<br />

dry. (Our note: ensure prawns are cooked<br />

through before serving. Undercooked shell<br />

fish can cause food poisoning.)<br />

Place the cooked prawn skewers onto<br />

a platter, and pour over the remaining<br />

flavoured butter. Top with parsley, a pinch<br />

of salt and a grind of black pepper.<br />

Serve with the lemon wedges. These are<br />

delicious peeled and dipped in aioli. Have a<br />

finger bowl and kitchen paper available.<br />

SUMMER <strong>2020</strong> | OPTIMUM NUTRITION<br />

31