Issue 109 / September 2020

September 2020 issue of Bido Lito! magazine. Featuring: TEE, JAMIE WEBSTER, ALL WE ARE, DECAY, MOLLY GREEN, FRAN DISLEY, FUTURE YARD, WHERE ARE THE GIRL BANDS and much more.

September 2020 issue of Bido Lito! magazine. Featuring: TEE, JAMIE WEBSTER, ALL WE ARE, DECAY, MOLLY GREEN, FRAN DISLEY, FUTURE YARD, WHERE ARE THE GIRL BANDS and much more.

Create successful ePaper yourself

Turn your PDF publications into a flip-book with our unique Google optimized e-Paper software.

on onboard computers. Those 60s urban planners could (just<br />

about) be forgiven for reading the signs as they did – cars were<br />

small, there was ignorance about fossil fuels, and the post-war<br />

project was utopian, in an individualist way. It wasn’t so long<br />

after, as that project began to sour, that it was plausible for the<br />

Prime Minister to have claimed that anyone over the age of 26<br />

riding a bus was a failure (some people need to sit at the front of<br />

the top deck more). That forecasting created a negative feedback<br />

loop which is still going.<br />

To be clear: this is not a crusade<br />

against all motor vehicles. Buses are<br />

vital, particularly for those with need<br />

of greater mobility and accessibility.<br />

In a city with a strong music scene<br />

and – yeuch, sorry to use this term –<br />

nocturnal economy, there still needs<br />

to be access for motor vehicles to<br />

load bands in and out, for vans to<br />

stock restaurants on Bold Street. But<br />

it should be equally safe for couriers<br />

and Deliveroo riders to navigate.<br />

Influential research conducted<br />

by New York City Department of<br />

Transport found that independent<br />

businesses fared better in districts<br />

with segregated cycle lanes. That<br />

might be a single piece of data but it<br />

opens up a rabbit hole about how cycling can be our means to an<br />

end too – the end being getting politicians to listen in terms they<br />

understand. And bikes are cool. They will never suffer the stigma<br />

other modes of transport have.<br />

On the face of it, competitive cycling’s had a positive<br />

influence on your average rider in the 2010s. Moves to ‘clean up’<br />

doping, a string of British Tour de France winners, and 2014’s<br />

Grand Départ in Yorkshire have almost certainly contributed to<br />

the increase of urban cycling, and not just at rush hour. But the<br />

“It’s not about<br />

picking a far-off<br />

date by which to lay<br />

more red tarmac;<br />

it’s about prioritising<br />

the cyclist from<br />

here on in”<br />

available data isn’t always so useful. Lists of ‘best and worst<br />

cities for cycling’ tend to draw on numbers of cyclists and<br />

Strava, and though that’s often shared with local authorities,<br />

it isn’t always easy to find out who cycles, why, and where to<br />

and from. Though we’ve all heard horror stories illustrated by<br />

footage of road rage and driving that, merely sloppy to the driver,<br />

is potentially lethal to the cyclist, it isn’t easy to track down<br />

quantified data about the cyclist’s experience and how safe they<br />

feel on the road.<br />

There is hard data about cycling<br />

fatalities. Liverpool came bottom<br />

in a Walk And Cycle Merseyside<br />

(WACM) table of metropolitan<br />

boroughs, with 42 deaths per<br />

100,000 of the population (the UK<br />

average is 29/100,000) between<br />

2014 and 2018, and Sefton sits<br />

only a few places higher. Focusing<br />

on fatalities and injuries among<br />

child cyclists, the North West<br />

fares little better, with St. Helens,<br />

Liverpool, Sefton and Wirral in the<br />

bottom 10. But it’s hard to parse<br />

the data (not every local authority<br />

is a metropolitan borough) and put<br />

it in context – higher numbers of<br />

cyclists may imply a greater risk of<br />

injury, but most cycle lanes in Liverpool so far have been painted<br />

on, rather than segregated from other traffic. Cyclists can only<br />

protect themselves so much. Here’s the rub: should building<br />

bike-friendly infrastructure encourage and determine future use,<br />

or reflect and improve the current cycling experience?<br />

Syd Barrett’s Bike occupies the God tier of bike songs. It’s<br />

a very good song but it’s not really about bikes, a bit like many<br />

cycling initiatives at local government level. Similar language<br />

appears over and over in plans for improved conditions for<br />

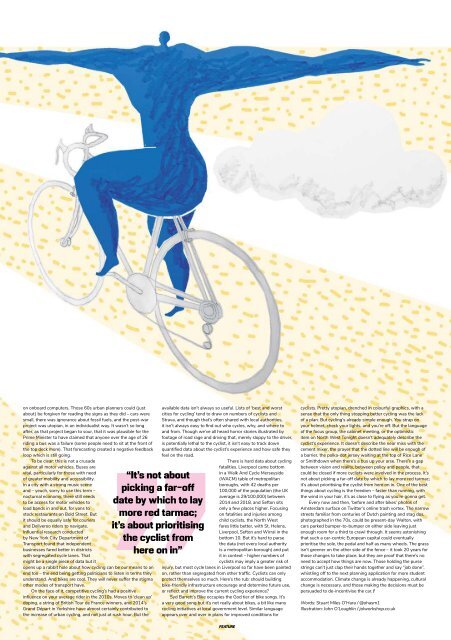

cyclists. Pretty utopian, drenched in colourful graphics, with a<br />

sense that the only thing stopping better cycling was the lack<br />

of a plan. But cycling’s already simple enough. You strap on<br />

your helmet, check your lights, and you’re off. But the language<br />

of the focus group, the cabinet meeting, or the optimistic<br />

item on North West Tonight doesn’t adequately describe the<br />

cyclist’s experience. It doesn’t describe the near miss with the<br />

cement mixer, the prayer that the dotted line will be enough of<br />

a barrier, the polka-dot jersey waiting at the top of Rice Lane<br />

or Smithdown when there’s a bus up your arse. There’s a gap<br />

between vision and reality, between policy and people, that<br />

could be closed if more cyclists were involved in the process. It’s<br />

not about picking a far-off date by which to lay more red tarmac;<br />

it’s about prioritising the cyclist from here on in. One of the best<br />

things about cycling is the freedom – faster than running, with<br />

the wind in your hair, it’s as close to flying as you’re gonna get.<br />

Every now and then, ‘before and after bikes’ photos of<br />

Amsterdam surface on Twitter’s online trash vortex. The narrow<br />

streets familiar from centuries of Dutch painting and stag dos,<br />

photographed in the 70s, could be present-day Walton, with<br />

cars parked bumper-to-bumper on either side leaving just<br />

enough room for a third to crawl through. It seems astonishing<br />

that such a car-centric European capital could eventually<br />

prioritise the sole, the pedal and half as many wheels. The grass<br />

isn’t greener on the other side of the fence – it took 20 years for<br />

those changes to take place, but they are proof that there’s no<br />

need to accept how things are now. Those holding the purse<br />

strings can’t just clap their hands together and say “job done”,<br />

whistling off to the next planning application for more student<br />

accommodation. Climate change is already happening, cultural<br />

change is necessary, and those making the decisions must be<br />

persuaded to de-incentivise the car. !<br />

Words: Stuart Miles O’Hara / @ohasm1<br />

Illustration: John O’Loughlin / jolworkshop.co.uk<br />

FEATURE<br />

33